Abstract

Autophagy is a conserved multi-step lysosomal process that is induced by diverse stimuli including cellular nutrient deficiency. X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) promotes cell survival and recently has been demonstrated to suppress autophagy. Herein, we examined regulation of XIAP-mediated autophagy in breast cancer cells and determined the underlying molecular mechanism. To investigate this process, autophagy of breast cancer cells was induced by Earle's balanced salt solution (EBSS). We observed discordant expression of XIAP mRNA and protein in the autophagic process induced by EBSS, suggesting XIAP may be regulated at a post-transcriptional level. By scanning several miRNAs potentially targeting XIAP, we observed that forced expression of miR-23a significantly decreased the expression of XIAP and promoted autophagy, wherever down-regulation of miR-23a increased XIAPexpression and suppressed autophagy in breast cancer cells. XIAP was confirmed as a direct target of miR-23a by reporter assay utilizing the 3′UTR of XIAP. In vitro, forced expression of miR-23a promoted autophagy, colony formation, migration and invasion of breast cancer cell by down-regulation of XIAP expression. However, miR-23a inhibited apoptosis of breast cancer cells independent of XIAP. Xenograft models confirmed the effect of miR-23a on expression of XIAP and LC3 and that miR-23a promoted breast cancer cell invasiveness. Therefore, our study demonstrates that miR-23a modulates XIAP-mediated autophagy and promotes survival and migration in breast cancer cells and hence provides important new insights into the understanding of the development and progression of breast cancer.

Keywords: miR-23a, autophagy, XIAP, breast cancer

INTRODUCTION

Autophagy is a cell self-degradation process for long-lived proteins and damaged organelles. Autophagy is present in cells at a low basal level and can be promoted by diverse stressful conditions, such as adaptation to starvation, oxidative or genotoxic stress, and elimination of pathogens [1, 2]. The role of autophagy in cancer development and progression remains ambiguous. Different studies have demonstrated that autophagic process may function in both a tumor suppressor and oncogenic role [3, 4]. In vivo depletion of the expression of autophagy-related genes, such as BECN1 and ATG5, has been reported to lead to tumor cell survival [5–8]. In contrast, autophagy may enhance tumor cell survival, especially in oncogenic RAS-driven cancer [9–11]. Hence, a better molecular understanding of the autophagic process will assist in delineating its roles in cancer progression.

X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP), is a member of the “inhibitors of apoptosis” (IAP) family and characterized by the presence of at least one baculovirus IAP repeat (BIR) structural domain [12]. XIAP possesses the most potent anti-apoptotic capacity by binding and inhibiting of caspases (caspase-3, 7, and 9) in vitro [13, 14]. XIAP protein levels are regulated both transcriptionally and post-transcriptionally [15–18]. Our recent study demonstrated that XIAP was able to suppress autophagic activity of diverse tumor cell types by the Mdm2-p53 pathway independent of its anti-apoptosis function [19, 20]. However, the mechanism involved in the regulation of XIAP in autophagy is unknown.

Recent studies have identified microRNAs (miRNAs) as novel regulators of autophagy [21–23]. miRNAs are short (19∼25 nucleotides) non-coding RNAs, which may act as negative regulators of gene expression by binding to a target mRNA, resulting in posttranscriptional or translational repression [24, 25]. To date, only a few of miRNAs have been reported to modulate autophagic activity directly. MiR-30d was observed to impair the autophagic process by targeting multiple genes in the autophagic pathway [26]. miR-376a regulates starvation-induced autophagy by controlling of ATG4C and BECN1 transcript and protein levels [27]. MiR-199a-5p plays differential roles in radiation-induced autophagy in breast cancer cells by regulating the expression level of DRAM1 and BECN1 [28]. Herein, to investigate the regulatory mechanism of XIAP in cell autophagy, we scanned several miRNAs and identified miR-23a as a target miRNA for XIAP-mediated autophagy and also play a role in cell viability, invasion and migration of breast cancer.

RESULTS

Autophagy are associated with XIAP

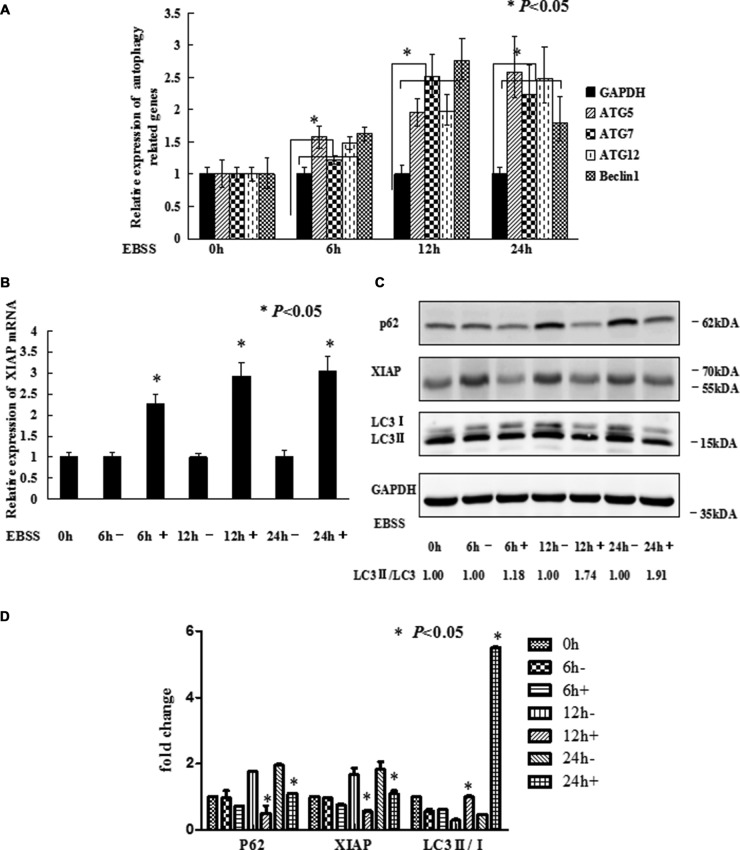

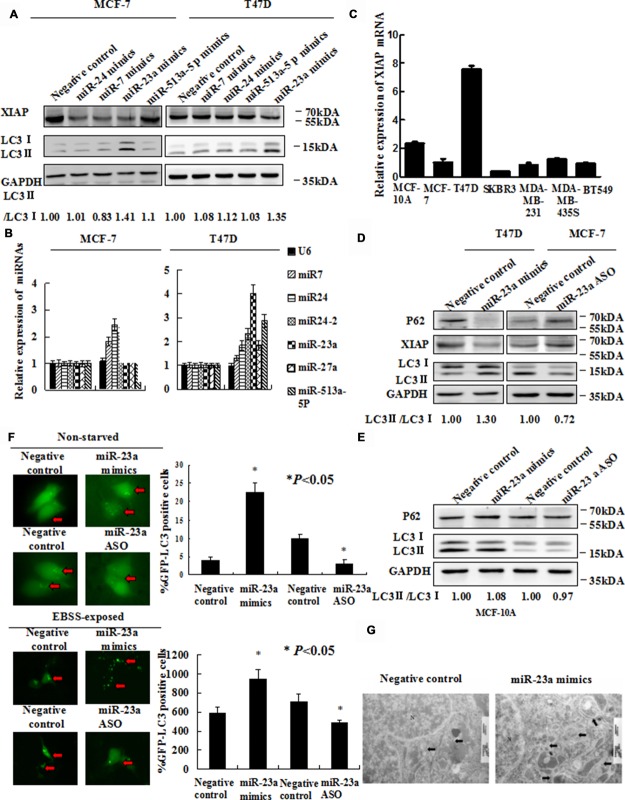

To trigger autophagy, MCF-7 cells were cultured with or without Earle's balanced salt solution (EBSS) in a time-dependent manner. As reported in our previous study, XIAP inhibited autophagy via XIAP-Mdm2-p53 signaling pathway [19]. QRT-PCR was performed to ensure the expression of XIAP and autophagy related genes including ATG5, ATG7, ATG12 and Beclin1. As shown in Figure 1A, the expression levels of the autophagy related genes were all increased, which suggested that EBSS induced autophagy in these cells. Meanwhile, the expression level of XIAP mRNA was also increased (Figure 1B). To verify these results, we further analyzed the protein levels of XIAP and determined the conversion of LC3-I (cytosolic form) to LC3-II (membrane-bound lipidated form) by Western blot analysis. To our surprise, the protein level of XIAP was decreased, and LC3-II/LC3-I conversion ratio was increased, in the presence of EBSS (Figure 1C). The gray value we calculated as shown in Figure 1D. We also used 3-MA, an autophagy inhibitor, in the EBSS-exposed cells, and the expression level of SQSTM1/P62 protein was increased and LC3-II/LC3-I conversion ratio was decreased. This result clarified the observed increase in LC3-II is suggestive of induction of autophagy (Supplementary Figure 1). Hence, there exists discordance between XIAP mRNA and protein levels in the process of autophagy, suggesting that XIAP may be regulated at a post-transcriptional level, potentially by miRNAs. To determine whether miRNAs potentially participated in regulating autophagy, we identified several miRNAs potentially targeting XIAP by bioinformatic analysis, including miR-24, miR-7, miR-23a and miR-513a-5p. Of these miRNAs, miR-23a not only significantly down-regulated the expression of XIAP, but also increased LC3-II/LC3-I conversion ratio in both MCF-7 and T47D cells (Figure 2A). We therefore selected miR-23a to further investigate the influence of miRNAs on XIAP-mediated autophagy.

Figure 1. EBSS induces autophagy in breast cancer cells.

(A and B) MCF-7 cells at 80%–90% confluence were cultured with EBSS for 0, 6, 12, and 24 h, compared with normal medium. Cells were collected for qRT-PCR to quantify the expression level of the autophagy related genes and XIAP. The error bars indicate the standard error of the mean (S.E.M) for three independent experiments (*, P < 0.05). (C) Western blot analysis of XIAP and LC3-II/I expression after MCF-7 cells treated with EBSS. (D) The gray value of P62, XIAP and LC3-II/I was calculated.

Figure 2. Forced expression of miR-23a induces autophagic activity.

(A) MCF-7 and T47D cells were transfected with miR-24 mimics, miR-7 mimics, miR-23a mimics and miR-513a-5p mimics. Forty-eight hours later, LC3-II/I proteins were detected by Western blot. (B) EBSS induced miR-23a expression strongly in MCF-7 and T47D cells. Cells were treated with EBSS and compared cells grown in with normal medium. Shown is the qRT-PCR analysis for miR-24, miR-7, miR-513a-5p and miR-23a. U6 snRNA was used as an input control (*, P < 0.05). (C) XIAP mRNA expression in seven human mammary cell lines was analyzed by qRT-PCR. (D) Expression of miR-23a induces LC3 conversion and SQSTM1/P62 degradation. T47D cells were transiently transfected with miR-23a mimics and MCF-7 cells were transiently transfected with miR-23a ASO. Total cellular protein was isolated and subjected to Western blot analysis. GAPDH was used as input control. (E) Expression of miR-23a did not significantly induce LC3 conversion and SQSTM1/P62 degradation. MCF-10A cells were transiently transfected with miR-23a mimics and miR-23a ASO. Total cellular protein was isolated and subjected to Western blot analysis. GAPDH was used as input control. (F) GFP-LC3 puncta formation was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (200× magnification). Black arrows indicate clusters of GFP-LC3 puncta in cells. Quantification of GFP-LC3 puncta in E (mean ± S.D of independent experiments, n = 3,*P < 0.05). (G) Autophagy was evaluated in breast cancer cells by electron microscopy. Scale bars, 200 nm.

Overexpression of miR-23a enhanced autophagy

To explore the role of miRNAs in autophagy, we performed qRT-PCR analysis for the expression levels of miR-24, miR-7, miR-513a-5p and miR-23a in MCF-7 and T47D cells treated with EBSS. The level of miR-23a expression was the most increased of 4 miRNAs in cells cultured with EBSS, compared with cells cultured with normal medium (Figure 2B). By determination of XIAP expression in common mammary epithelial and breast cancer cell lines, we selected T47D and MCF-7, as a couple of model cell lines with relatively high and low expression of XIAP respectively (Figure 2C). We performed Western blot analysis to detect LC3-II/LC3-I conversion ratio in T47D and MCF-7 cells after transfection with miR-23a mimics and miR-23a ASO, respectively. MiR-23a mimics diminished the expression of SQSTM1/P62 protein and increased LC3-II/LC3-I conversion ratio in T47D cells. In contrast, miR-23a ASO significantly increased the expression of SQSTM1/P62 protein and decreased LC3-II / LC3-I conversion ratio in MCF-7 cells (Figure 2D). However, there is not a significant change about the expression of SQSTM1/P62 and XIAP protein after transfection with miR-23a mimics or ASO in non-tumorigenic MCF-10A (Figure 2E). Next, miR-23a mimics and miR-23a ASO, respectively, were transfected into T47D and MCF-7 cells together with the GFP-LC3 plasmid and examined by fluorescence microscopy. As shown in Figure 2F, there was a significant increase of GFP-LC3 puncta in miR-23a mimics transfected cells and a decrease of GFP-LC3 puncta in miR-23a ASO transfected cells both in non-starved and EBSS-exposed breast cancer cells. Consistent with the GFP-LC3 puncta formation assay, we observed that accumulation of autophagosomes was increased in miR-23a mimics transfected cells by transmission electron microscopy (Figure 2G).

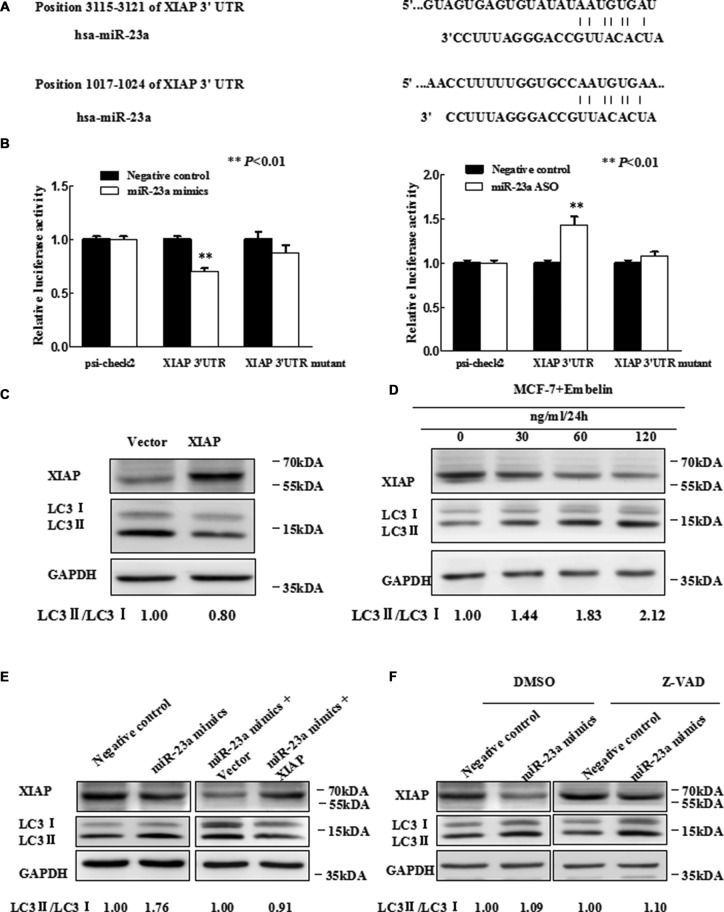

MiR-23a directly targeted XIAP 3′UTR

Having established the function of miR-23a in autophagy, we next determined whether miR-23a directly targeted XIAP. Firstly, we identified two potential binding sites of miR-23a in the XIAP-3′UTR by Targetscan [29] (Figure 3A). We then performed qRT-PCR to examine the level of XIAP mRNA in cells transfected with miR-23a mimics and miR-23a ASO. As shown in Supplementary Figure 2, miR-23a produced a slight decrease in the XIAP mRNA level and miR-23a ASO exerted the opposite effect. Western blot analysis showed that the cellular levels of XIAP protein were significantly decreased in miR-23a mimics transfected cells and significantly increased in miR-23a ASO transfected cells (Figure 2D).

Figure 3. MiR-23a directly targets XIAP 3′UTR.

(A) Predicted binding sequences between miR-23a and seed matches in XIAP-3′UTR. (B) Luciferase reporter analysis of XIAP 3′UTR were performed after co-transfection with miR-23a in T47D cells and after co-transfection with miR-23a ASO in MCF-7 cells. The error bars indicate the standard error of the mean (S.E.M.) for three independent experiments (*P < 0.05). (C) Expression of XIAP inhibits autophagy. Western blot analysis is shown. Vector is used as an internal control. (D) MCF-7 cells were treated with Embelin as indicated and XIAP protein level and LC3-II/I expression were determined by Western blot analysis with anti-XIAP and anti-LC3, respectively. (E) Western blot. T47D cells were grown and transfected with miR-23a mimics, miR-23a mimics plus vector, miR-23a mimics plus expression of XIAP, or negative control. Then, total cellular proteins from these cells were subjected to Western blot analysis of XIAP, LC3 expression. (F) Western blot. Forty-eight hours after transfected with miR-23a mimics and Negative control in T47D cells, which were treated with 20 uM Z-VAD-FMK or DMSO for 2 h. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting.

Luciferase reporter assay demonstrated that miR-23a directly interacted with XIAP 3′UTR and this interaction occurred at positions 3115-3121 (Figure 3B), but not positions 1017–1024 (data not shown). We next determined whether promotion of autophagy by miR-23a was mediated by XIAP. We first constructed a XIAP expression vector, pIRESneo3/XIAP, and the forced expression of XIAP was confirmed by qRT-PCR (Supplementary Figure 3) and Western blot analysis (Figure 3C). We also used Embelin, an inhibitor of XIAP, to verify the function of XIAP on autophagy, by Western blot analysis for LC3-II/LC3-I (Figure 3D). We observed that Embelin promoted autophagy in a dose-dependent manner (0–120 ug/ml). By transfection of miR-23a mimics, miR-23a mimics plus XIAP expression plasmid or controls, we observed that forced expression of XIAP significantly abrogated miR-23a-induced autophagy in T47D cells (Figure 3E).

For the essential role of XIAP in regulating cell apoptosis, we may ask that whether miR-23a-induced autophagy was associated with apoptosis. To this end, we transfected T47D cells with miR-23a mimics or a negative control followed by treatment with either caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK or vehicle (DMSO). It was observed that the effect of miR-23a on LC3-II/LC3-I conversion ratio and the protein level of XIAP in T47D cells was not affected by Z-VAD-FMK treatment (Figure 3F), suggesting that miR-23a induced XIAP-mediated autophagy was independent of caspase-mediated apoptosis.

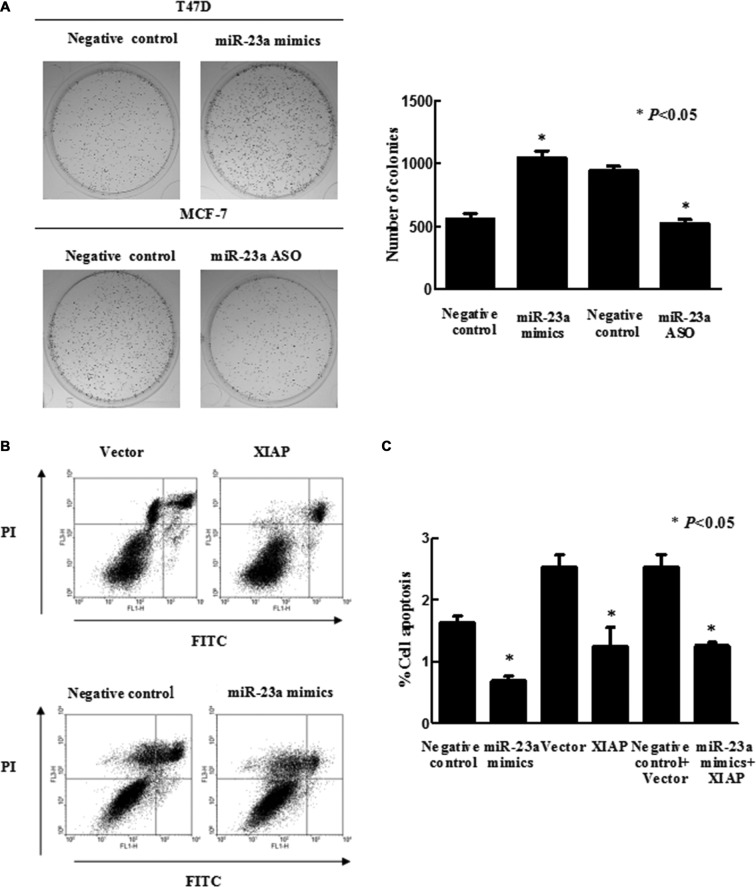

Effects of miR-23a on breast cancer cell viability, migration, invasion and apoptosis

We next explored the effect of miR-23a on the behaviors of breast cancer cells in vitro. We observed that knockdown of miR-23a expression in MCF-7 cells by miR-23a ASO did not significantly alter cell viability (P > 0.05), and forced-expression of miR-23a in T47D cells by miR-23a mimics did not significantly reduce cell viability (P > 0.05) in MTT assay (data not shown). However, in a long-term cell survival assay, up-regulation of miR-23a expression by transfecting T47D cells with the specific mimics significantly increased cell colony formation, and downregulation of miR-23a expression by transfecting MCF-7 cells with the specific ASO significantly decreased cell colony formation (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Effects of miR-23a on breast cancer cell viability and apoptosis.

(A) Colony formation assays. T47D and MCF-7 cells were grown and transiently transfected with miR-23a mimics and miR-23a ASO, respectively, and then seeded in 0.35% top agarose and 10% FBS in six-well plates in triplicate. The number of colonies was counted after 10 days incubation. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis in T47D cells after genes transfection, as evidenced by PI/Annexin V double staining and FACS analysis. (C) The apoptosis rate was quantified by a flow cytometer. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3, *P < 0.05).

We next used transwell assays to assess the impact of miR-23a on cell migration and invasion. As shown in Supplementary Figure 4, T47D cells transfected with miR-23a mimics exhibited increased migration and invasion compared with controls. Moreover, co-transfection of cells with miR-23a mimics and the XIAP expression plasmid demonstrated that expression of XIAP significantly abrogated miR-23a mimic-promoted tumor cell migration and invasion (Supplementary Figure 4A). Furthermore, 48 h after transient transfection of miR-23a mimics, cells were treated with the autophagy inhibitor 3-MA for 24h. 3-MA significantly abrogated miR-23a mimic-promoted tumor cell migration and invasion (Supplementary Figure 4B). Consistently, MCF-7 cells transfected with miR-23a ASO exhibited decreased migration and invasion, compared with the control. Moreover, XIAP inhibitor Embelin and autophagy inducer EBSS dramatically abrogated miR-23a ASO-decreased tumor cell migration and invasion (Supplementary Figure 4C, 4D). These data implied that miR-23a promoted autophagy and cell migration and invasion using similar signaling pathways by regulation of XIAP.

Previous studies have demonstrated that miR-23a suppressed apoptosis in colorectal and gastric cancer cells [30, 31]. Consistently, we observed that miR-23a significantly inhibited apoptosis of breast cancer cells (Figure 4B). Next, we determined whether XIAP was involved in miR-23a-regulated apoptosis. To this end, we transfected miR-23a mimics, miR-23a mimics plus XIAP expression plasmid or controls into T47D cells and observed that forced-expression of XIAP did not abrogate the anti-apoptotic effect of miR-23a in these cells (Figure 4C).

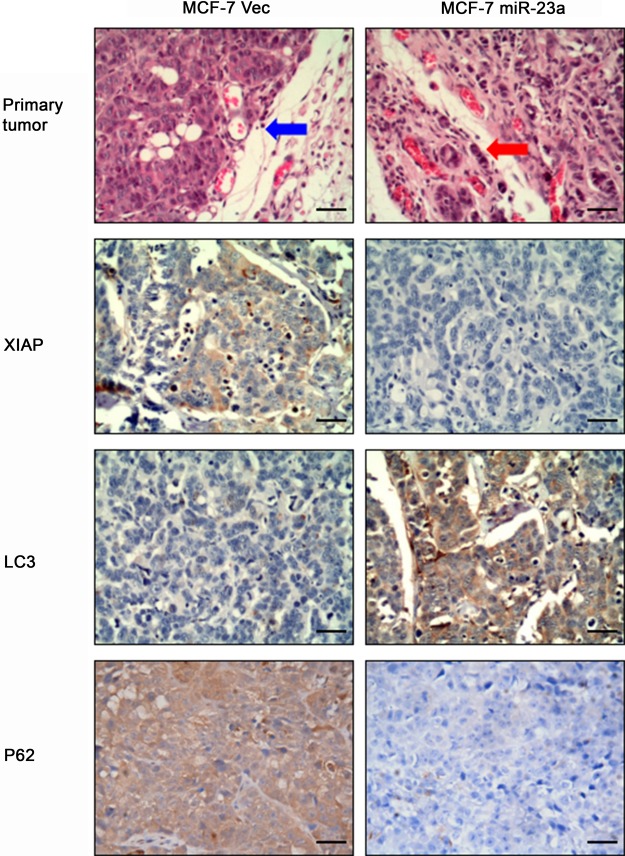

Effects of miR-23a on XIAP expression and tumor cell invasiveness in nude mouse xenografts

To determine the effect of miR-23a expression in breast cancer cells in vivo, we injected MCF-7-VEC and MCF-7-miR-23a cells orthotopically into the mammary fat pad of female BALB/c nude mice, respectively. Histology of xenografts showed that tumors derived from MCF-7-miR-23a cells were poorly encapsulated and highly invasive in comparison to tumors derived from control cells (Figure 5). More aggressive behavior was observed in the margin of tumor nodule of MCF-7-miR-23a cells (red arrow) compared to that of MCF-7-VEC cells (blue arrow). By use of immunohistochemistry, we also confirmed decreased protein expression ofXIAP, P62 and increased LC3 expression in tumors generated by MCF-7-miR-23a cells compared to those generated by control cells (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Effects of forced expression miR-23a on regulation of MCF-7 xenograft in nude mice.

MCF-7-Negative control and MCF-7- miR-23a cells were transplanted into the mammary fat pad of female BALB/c-nu, respectively. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of tumor xenograft sections. Invasive behavior was observed at the margin of the tumors generated by MCF-7-miR-23a mimics (red arrow) compared to that of MCF-7-Negative control cells (blue arrow). (Magnification: ×200). Representative imagines of XIAP, LC3 and P62 expression analyzed by immunohistochemistry (Magnification: ×200).

DISCUSSION

We have previously demonstrated that XIAP suppressed diverse cell autophagy independent of its regulation of apoptosis [19]. However, the upstream regulation of XIAP-mediated autophagy is unknown. We observed discordant expression of XIAP mRNA and protein after induction of autophagy which implied that XIAP may be post-transcriptionally regulated. We first identified miR-23a as a regulator of autophagy and demonstrated that XIAP is a target gene of miR-23a. Finally, we demonstrated that miR-23a enhanced breast cancer cell autophagic activity through modulation of XIAP expression and also promoted cell migration and invasion.

The function of autophagy in cancer development and/or progression is considered to be cell context-dependent [4, 32]. Autophagy ensures the delivery of metabolic substrates to cells so as to fulfill their energy demand during stress, thus supporting cell survival [33, 34]. However, hyperactivation of autophagy will result in cell death designated as ‘autophagic cell death’. Amino acid deprivation promotes autophagy in different organs and in cultured cells [35, 36]. Consistent with these reports, we have demonstrated that amino acid deficient increased autophagy activity in breast cancer cells.

It has been reported that the process of autophagy is modulated by miRNAs that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally [21–23]. In the present study, we have identified miR-23a as a novel miRNA regulating basal autophagy. MiR-23a expression has been reported in a wide range of malignancies, including gastric, colorectal, and breast cancers [30, 31, 37]. Several lines of evidence suggest that miR-23a functions as an oncogene and is involved in tumor development. Herein, we demonstrated that forced expression of miR-23a inhibits apoptosis, promotes autophagy and enhances cell colony formation, migration and invasion. It was interesting to note that expression of endogenous miR-23a was increased in response to cellular stress caused by amino acid depletion. Transcriptional and/or post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms may be responsible for increased miR-23a expression. In MCF-7 and T47D cell lines, we found that forced expression of miR-23a resulted in a significant increase LC3-II accumulation and SQSTM1/P62 degradation. In addition, suppression of miR-23a by specific antagonism exerted the opposite effect. While there was no significant change concerning P62 and LC3-II/I expression after transfection of miR-23a mimics or ASO in MCF-10A cell line. Our results support the idea that there were differences between miR-23a regulated cell lines. We further observed by transmission electron microscopy that accumulation of autophagosomes was increased in cells transfected with miR-23a and concordantly observed enhancement of GFP-LC3 puncta formation by fluorescence microscopy.

One miRNA may modulate the expression of different target genes. By using bioinformatic analyses to search for potential target genes of miR-23a, we observed that miR-23a may directly target XIAP mRNA. Experimentally by use of reporter assays we observed that XIAP was indeed a target gene of miR-23a as expected. The mechanisms of miR-23a-promoted cell autophagy, survival, migration and invasion required further delineation. We demonstrated that increased XIAP expression significantly abrogated miR-23a mimics-promoted breast cancer cell autophagy, migration and invasion. Furthermore, 3-MA decreased miR-23a mimics-induced cell migration and invasion. However, the two processes of autophagy and cell migration/invasion may simply utilize similar signaling pathways and not be functionally or causally related 3-MA inhibits autophagy by acting as an inhibitor of type III PI3K [38, 39]. Enhanced PI3K activity has also been demonstrated to promote human fibrosarcoma cell migration and invasion [40]. Additionally, XIAP is the most potent caspase inhibitor of all IAP family members and has been observed to be increased in expression in a variety of human malignancies [41–45]. Hence we determined whether a potential functional interrelationship existed between XIAP-mediated autophagy and XIAP mediated cell survival. We demonstrated that miR-23a promoted XIAP-mediated autophagy was independent of the caspase-mediated apoptotic pathway. Interestingly, our data also revealed that miR-23a did indeed inhibit cell apoptosis but this function was not mediated by XIAP. The results are not surprising as one miRNA may modulate the expression of different target genes with a differential functional outcome dependent on the particular cellular context. For example, Xie et al. [16] showed that miR-24 over-expression can overcome apoptosis-resistance in cancer cells via downregulation of XIAP expression. Liu et al. [30] demonstrated that miR-23a suppressed apoptosis of gastric cancer cells by targeting the PPP2R5E gene. Herein, suppression of breast cancer cell apoptosis by miR-23a is probably mediated by some other genes rather than XIAP.

Interestingly, the basal levels of XIAP in MCF-7 and T47D cells were discrepant, and the mRNA level of XIAP in T47D was nearly 8 times of that in MCF-7 (Figure 2C). As reported previously, many proteins involved in stimulation of cell growth, cell survival and cancer development were expressed more strongly in T47D than in MCF7 including for example, cyclin-D3 and prohibitin [46, 47]. Herein we consistently observed that the anti-apoptosis and anti-autophagic gene XIAP was also dramatically higher in T47D compared with MCF-7.

A compensatory mechanism that leads to increased expression of other IAP family members when XIAP expression is lost during apoptosis has been observed [48]. This work shed light on the independent relationship between autophagy and apoptosis mediated by miR-23a. It is reported that miR-21, miR-155, and miR-221/222 may also mediate apoptotic and autophagic pathways of glioma cells, cervical cancer cells and breast cancer cells, respectively [49–52]. Similarly, we demonstrated that miR-23a promotes autophagy and inhibits apoptosis by different mechanisms in breast cancer cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and treatment

Human breast cancer cell lines MCF-7, T47D, SKBR3, BT549, MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-435S and a human breast non-tumorigenic cell line MCF-10A were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). All cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were treated with Earle's balanced salt solution (EBSS, Sigma) to activate starvation-induced autophagy [27]. Apoptosis inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK (Santa Cruz), autophagy inhibitor 3-MA (Sigma) and XIAP inhibitor Embelin (Santa Cruz) were treated when necessary.

MiRNA transfection

Breast cancer T47D and MCF-7 cells (1.0 × 105 /well) were seeded in 6-well plates overnight and then respectively transfected with miR-23a mimics (GenePharma, Shanghai) or its negative control and 2′-O methylated single-stranded miR-23a antisense oligonucleotide (ASO, GenePharma) or its negative control, and RNA duplex control using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif, CA, USA) following the instructions of the manufacturer. The sequences of miRNA oligonucleotides were summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total cellular RNA and miRNA were isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and the mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX), respectively, according to the manufacturer's introductions. QRT-PCR were performed to detect the expression of XIAP, ATG5, ATG7, ATG12, Beclin1, miR-23a, GAPDH, and U6 as described previously [53–55]. The sequence of the primers used for qRT-PCR was summarized in Supplementary Table 2.

Western blotting analysis

Total cellular protein and Western blotting analysis were performed according to pervious study [53, 54]. The antibodies used were as follows: anti-XIAP (E-2, Santa Cruz), anti-LC3 (L7543, Sigma), anti-SQSTM1/P62 (D-3, Santa Cruz), anti-GAPDH (A-3, Santa Cruz).

Immunohistochemistry assay

For analysis of XIAP expression and LC3 expression in tumors from nude mouse, a mouse anti-XIAP polyclonal antibody (H-202, Santa Cruz, 1:15) and a rabbit anti-LC3 polyclonal antibody (L7543, Sigma, 1:100) were used according to our previous study [53–55].

FACS analysis

Cell apoptosis was assayed using Annexin V- Apotosis Detection kit (BestBio, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer's introductions. All the experiments were performed using a FACScalibur cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Each experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated at least once.

GFP-LC3 Localization assay

In order to generate expression of GFP-LC3 in MCF-7 cells, we transiently expressed miR-23a and miR-23a ASO with the autophagy marker GFP-LC3, compared with negative control, 48h after co-transfection, GFP-LC3 puncta were visualized under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus XSZ-D2) equipped with CCD cameras and images were captured and analyzed for presence of more than five puncta per cell.

Electron microscopy

Cells were treated as indicated and fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde containing 0.1 mol/L sodium cacodylate. Samples were fixed using 1% osmium tetroxide, followed by dehydration with an increasing concentration gradient of ethanol and propylene oxide. Samples were then embedded, cut into 50nm sections, and stained with 3% uranyl acetate and lead citrate as previously reported [19]. Images were acquired using a JEM-1200 electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

Luciferase reporter assay

Cells were plated on a 24-well plate 24h before transfection at 50% confluence and then co-transfected with 0.2 ug of psiCHECK2-XIAP 3′UTR or psiCHECK2 control vector and 30 nM miR-23a mimics or its negative control by using Lipofectamine 3000. 48h after transfection, cells were harvested, and reporter assays were performed using a dual luciferase assay system (Promega). Each transfection was performed in triplicate. The primers for XIAP 3′UTR were 5′-GCGCGCACTCGA GTCTAACTCTATAGTAGGCATGTTATG-3′ (sense) and 5′-TATATGCGGCCGCCTACAATGAATGCCAGA TTATACAGC-3′ (antisense).

MTT assay and colony formation assay

Cells were cultured in 96-well plates at 5000 cells per well, 24h after transfection. The 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was used to determine cell viability 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, and 96 h after the cells were seed. Absorbance at 570 nm was measured using an automatic microplate reader. (Infinite M200; Tecan, Grodig, Austria). Next, the cells were cultured for 10 days, and colonies were counted. The experiment was performed in triplicate. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Cell migration and invasion assay

To determine whether the effect of miR-23a on breast cancer cell migration and invasion was medicated by XIAP in vitro, we used a Transwell insert (8 μm, Corning, NY). T47D cells were transfected with negative control, miR-23a mimics and miR-23a mimics plus plasmid XIAP or an autophagy inhibitor, 3-MA. Meanwhile, negative control, miR-23a ASO and miR-23a ASO plus XIAP inhibitor Embelin or EBSS were transfected in MCF-7 cells. Transwell assays were performed as described previously [53–55]. Five macroscopic areas were selected randomly and counted the cell numbers. All experiments were experiment in triplicate.

Nude mouse breast cancer cell xenograft assay

All animal work was performed according to Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines (available at www.iacuc.org) with local institutional approval. Briefly, the 5-week-old female BALB/c nude mice (Hunan SJA Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd.) were used for studies. 5 × 106 MCF-7-VEC and MCF-7-miR-23a cells were suspended in 120 μl Matrigel /PBS at a ratio of 1:1 (v/v) and then injected into the mammary fat pad of female BALB/c-nu. One estrogen pellet was implanted into each mouse before injection. When animals were sacrificed, primary tumors were harvested for further analysis.

Bioinformatic analysis and statistical analysis

The miRNA database TargetScan (release 5.1, http://www.targetscan.org/) was used to predict the targeting miRNAs of XIAP. Statistical evaluation was shown as means ± standard deviation (SD). Date was analyzed by SPSS 16.0 software. Differences between groups were compared using Student t test for continuous variables. P values were considered significance if P < 0.05.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURES AND TABLES

Footnotes

Author contributions

PC, YHH, XH, SQT, HY and WYW performed experiments and summarized the data; WYW, XNW, KSD and ZSW designed experiments; YHH, PEL and ZSW drafted the manuscript and critically discussed the data and manuscript; all authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there was no competing interest in this work.

FUNDING

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Nature Science Foundation of China (#81472493, 81572305 and 81372476), the Program for Excellent Talents and the scientific research program from Anhui Medical University (2013xkj006), Anhui provincial academic and technical leader reserve candidate (#2016H074), Key Program of Outstanding Young Talents in Higher Education Institutions of Anhui (#gxyqZD2016046), the Program for youth scientific research star from the Second affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University (2014KA02).

REFERENCES

- 1.Rabinowitz JD, White E. Autophagy and metabolism. Science. 2010;330:1344–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1193497. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1193497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhutia SK, Mukhopadhyay S, Sinha N, Das DN, Panda PK, Patra SK, Maiti TK, Mandal M, Dent P, Wang XY, Das SK, Sarkar D, Fisher PB. Autophagy: cancer's friend or foe? Adv Cancer Res. 2013;118:61–95. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407173-5.00003-0. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407173-5.00003-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogier-Denis E, Codogno P. Autophagy: a barrier or an adaptive response to cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1603:113–28. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(03)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang XH, Jackson S, Seaman M, Brown K, Kempkes B, Hibshoosh H, Levine B. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature. 1999;402:672–6. doi: 10.1038/45257. https://doi.org/10.1038/45257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qu X, Yu J, Bhagat G, Furuya N, Hibshoosh H, Troxel A, Rosen J, Eskelinen EL, Mizushima N, Ohsumi Y, Cattoretti G, Levine B. Promotion of tumorigenesis by heterozygous disruption of the beclin 1 autophagy gene. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1809–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI20039. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI20039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takamura A, Komatsu M, Hara T, Sakamoto A, Kishi C, Waguri S, Eishi Y, Hino O, Tanaka K, Mizushima N. Autophagy-deficient mice develop multiple liver tumors. Genes Dev. 2011;25:795–800. doi: 10.1101/gad.2016211. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.2016211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yue Z, Jin S, Yang C, Levine AJ, Heintz N. Beclin 1, an autophagy gene essential for early embryonic development, is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15077–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2436255100. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2436255100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo JY, Chen HY, Mathew R, Fan J, Strohecker AM, Karsli-Uzunbas G, Kamphorst JJ, Chen G, Lemons JM, Karantza V, Coller HA, Dipaola RS, Gelinas C, et al. Activated Ras requires autophagy to maintain oxidative metabolism and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2011;25:460–70. doi: 10.1101/gad.2016311. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.2016311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lock R, Roy S, Kenific CM, Su JS, Salas E, Ronen SM, Debnath J. Autophagy facilitates glycolysis during Ras-mediated oncogenic transformation. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:165–78. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-06-0500. https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.E10-06-0500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang S, Wang X, Contino G, Liesa M, Sahin E, Ying H, Bause A, Li Y, Stommel JM, Dell’antonio G, Mautner J, Tonon G, Haigis M, et al. Pancreatic cancers require autophagy for tumor growth. Genes Dev. 2011;25:717–29. doi: 10.1101/gad.2016111. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.2016111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller LK. An exegesis of IAPs: salvation and surprises from BIR motifs. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:323–8. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01609-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deveraux QL, Takahashi R, Salvesen GS, Reed JC. X-linked IAP is a direct inhibitor of cell-death proteases. Nature. 1997;388:300–4. doi: 10.1038/40901. https://doi.org/10.1038/40901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eckelman BP, Salvesen GS, Scott FL. Human inhibitor of apoptosis proteins: why XIAP is the black sheep of the family. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:988–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400795. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.7400795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu S, Zhang P, Chen Z, Liu M, Li X, Tang H. MicroRNA-7 downregulates XIAP expression to suppress cell growth and promote apoptosis in cervical cancer cells. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:2247–53. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.05.054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2013.05.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie Y, Tobin LA, Camps J, Wangsa D, Yang J, Rao M, Witasp E, Awad KS, Yoo N, Ried T, Kwong KF. MicroRNA-24 regulates XIAP to reduce the apoptosis threshold in cancer cells. Oncogene. 2013;32:2442–51. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.258. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2012.258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin S, Moon KC, Park KU, Ha E. MicroRNA-513a-5p mediates TNF-alpha and LPS induced apoptosis via downregulation of X-linked inhibitor of apoptotic protein in endothelial cells. Biochimie. 2012;94:1431–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.03.023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2012.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siegel C, Li J, Liu F, Benashski SE, McCullough LD. miR-23a regulation of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) contributes to sex differences in the response to cerebral ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:11662–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102635108. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1102635108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang X, Wu Z, Mei Y, Wu M. XIAP inhibits autophagy via XIAP-Mdm2-p53 signalling. EMBO J. 2013;32:2204–16. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.133. https://doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2013.133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merlo P, Cecconi F. XIAP: inhibitor of two worlds. EMBO J. 2013;32:2187–8. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.152. https://doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2013.152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frankel LB, Lund AH. MicroRNA regulation of autophagy. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:2018–25. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs266. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgs266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tekirdag KA, Korkmaz G, Ozturk DG, Agami R, Gozuacik D. MIR181A regulates starvation- and rapamycin-induced autophagy through targeting of ATG5. Autophagy. 2013;9:374–85. doi: 10.4161/auto.23117. https://doi.org/10.4161/auto.23117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korkmaz G, le Sage C, Tekirdag KA, Agami R, Gozuacik D. miR-376b controls starvation and mTOR inhibition-related autophagy by targeting ATG4C and BECN1. Autophagy. 2012;8:165–76. doi: 10.4161/auto.8.2.18351. https://doi.org/10.4161/auto.8.2.18351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–5. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russo G, Giordano A. miRNAs: from biogenesis to networks. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;563:303–52. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-175-2_17. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-60761-175-2_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang X, Zhong X, Tanyi JL, Shen J, Xu C, Gao P, Zheng TM, DeMichele A, Zhang L. mir-30d Regulates multiple genes in the autophagy pathway and impairs autophagy process in human cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;431:617–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.12.083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.12.083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korkmaz G, Tekirdag KA, Ozturk DG, Kosar A, Sezerman OU, Gozuacik D. MIR376A is a regulator of starvation-induced autophagy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082556. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0082556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yi H, Liang B, Jia J, Liang N, Xu H, Ju G, Ma S, Liu X. Differential roles of miR-199a-5p in radiation-induced autophagy in breast cancer cells. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:436–43. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.12.027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2012.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu X, Liu Q, Fan Y, Wang S, Liu X, Zhu L, Liu M, Tang H. Downregulation of PPP2R5E expression by miR-23a suppresses apoptosis to facilitate the growth of gastric cancer cells. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:3160–9. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.05.068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2014.05.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yong FL, Wang CW, Roslani AC, Law CW. The involvement of miR-23a/APAF1 regulation axis in colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:11713–29. doi: 10.3390/ijms150711713. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms150711713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hippert MM, O’Toole PS, Thorburn A. Autophagy in cancer: good, bad, or both? Cancer Res. 2006;66:9349–51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1597. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhutia SK, Kegelman TP, Das SK, Azab B, Su ZZ, Lee SG, Sarkar D, Fisher PB. Astrocyte elevated gene-1 induces protective autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:22243–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009479107. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1009479107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ouyang L, Shi Z, Zhao S, Wang FT, Zhou TT, Liu B, Bao JK. Programmed cell death pathways in cancer: a review of apoptosis, autophagy and programmed necrosis. Cell Prolif. 2012;45:487–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2012.00845.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2184.2012.00845.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mortimore GE, Poso AR, Lardeux BR. Mechanism and regulation of protein degradation in liver. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1989;5:49–70. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610050105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blommaart EF, Luiken JJ, Meijer AJ. Autophagic proteolysis: control and specificity. Histochem J. 1997;29:365–85. doi: 10.1023/a:1026486801018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li X, Liu X, Xu W, Zhou P, Gao P, Jiang S, Lobie PE, Zhu T. c-MYC-regulated miR-23a/24-2/27a cluster promotes mammary carcinoma cell invasion and hepatic metastasis by targeting Sprouty2. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:18121–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.478560. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M113.478560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petiot A, Ogier-Denis E, Blommaart EF, Meijer AJ, Codogno P. Distinct classes of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinases are involved in signaling pathways that control macroautophagy in HT-29 cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:992–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seglen PO, Gordon PB. 3-Methyladenine: specific inhibitor of autophagic/lysosomal protein degradation in isolated rat hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:1889–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.6.1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ito S, Koshikawa N, Mochizuki S, Takenaga K. 3-Methyladenine suppresses cell migration and invasion of HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells through inhibiting phosphoinositide 3-kinases independently of autophagy inhibition. Int J Oncol. 2007;31:261–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shaw TJ, Lacasse EC, Durkin JP, Vanderhyden BC. Downregulation of XIAP expression in ovarian cancer cells induces cell death in vitro and in vivo. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:1430–4. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23278. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.23278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dai Y, Qiao L, Chan KW, Zou B, Ma J, Lan HY, Gu Q, Li Z, Wang Y, Wong BL, Wong BC. Loss of XIAP sensitizes rosiglitazone-induced growth inhibition of colon cancer in vivo. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2858–63. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23443. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.23443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang SG, Ding F, Luo AP, Chen AG, Yu ZC, Ren SH, Liu ZH, Zhang L. XIAP is highly expressed in esophageal cancer and its downregulation by RNAi sensitizes esophageal carcinoma cell lines to chemotherapeutics. Cancer Biology & Therapy. 2007;6:973–9. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.6.4195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mizutani Y, Nakanishi H, Li YN, Matsubara H, Yamamoto K, Sato N, Shiraishi T, Nakamura T, Mikami K, Okihara K, Takaha N, Ukimura O, Kawauchi A, et al. Overexpression of XIAP expression in renal cell carcinoma predicts a worse prognosis. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:919–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giagkousiklidis S, Vellanki SH, Debatin KM, Fulda S. Sensitization of pancreatic carcinoma cells for gamma-irradiation-induced apoptosis by XIAP inhibition. Oncogene. 2007;26:7006–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210502. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1210502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aka JA, Lin SX. Comparison of Functional Proteomic Analyses of Human Breast Cancer Cell Lines T47D and MCF7. Plos One. 2012:7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031532. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0031532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Radde BN, Ivanova MM, Mai HX, Salabei JK, Hill BG, Klinge CM. Bioenergetic differences between MCF-7 and T47D breast cancer cells and their regulation by oestradiol and tamoxifen. Biochem J. 2015;465:49–61. doi: 10.1042/BJ20131608. https://doi.org/10.1042/bj20131608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harlin H, Reffey SB, Duckett CS, Lindsten T, Thompson CB. Characterization of XIAP-deficient mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3604–8. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.10.3604-3608.2001. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.21.10.3604-3608.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wan G, Xie WD, Liu ZY, Xu W, Lao YZ, Huang NN, Cui K, Liao MJ, He J, Jiang YY, Yang BB, Xu HX, Xu NH, et al. Hypoxia-induced MIR155 is a potent autophagy inducer by targeting multiple players in the MTOR pathway. Autophagy. 2014;10:70–9. doi: 10.4161/auto.26534. https://doi.org/10.4161/auto.26534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu J, Zhu HC, Yang X, Ge YY, Zhang C, Qin Q, Lu J, Zhan LL, Cheng HY, Sun XC. MicroRNA-21 is a novel promising target in cancer radiation therapy. Tumor Biology. 2014;35:3975–9. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1623-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13277-014-1623-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miller TE, Ghoshal K, Ramaswamy B, Roy S, Datta J, Shapiro CL, Jacob S, Majumder S. MicroRNA-221/222 Confers Tamoxifen Resistance in Breast Cancer by Targeting p27Kip1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:29897–903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804612200. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M804612200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen WX, Hu Q, Qiu MT, Zhong SL, Xu JJ, Tang JH, Zhao JH. miR-221/222: promising biomarkers for breast cancer. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:1361–70. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0750-y. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13277-013-0750-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu ZS, Wu Q, Wang CQ, Wang XN, Huang J, Zhao JJ, Mao SS, Zhang GH, Xu XC, Zhang N. miR-340 inhibition of breast cancer cell migration and invasion through targeting of oncoprotein c-Met. Cancer. 2011;117:2842–52. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25860. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu ZS, Wang CQ, Xiang R, Liu X, Ye S, Yang XQ, Zhang GH, Xu XC, Zhu T, Wu Q. Loss of miR-133a expression associated with poor survival of breast cancer and restoration of miR-133a expression inhibited breast cancer cell growth and invasion. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:51. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-51. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-12-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu ZS, Wu Q, Wang CQ, Wang XN, Wang Y, Zhao JJ, Mao SS, Zhang GH, Zhang N, Xu XC. MiR-339-5p inhibits breast cancer cell migration and invasion in vitro and may be a potential biomarker for breast cancer prognosis. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:542. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-542. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-10-542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.