Abstract

We have previously reported that oral biofilms in clinically healthy smokers are pathogen-rich, and that this enrichment occurs within 24 h of biofilm formation. The present investigation aimed to identify a mechanism by which smoking creates this altered community structure. By combining in vitro microbial–mucosal interface models of commensal (consisting of Streptococcus oralis, Streptococcus sanguis, Streptococcus mitis, Actinomyces naeslundii, Neisseria mucosa and Veillonella parvula) and pathogen-rich (comprising S.oralis, S.sanguis, S.mitis, A.naeslundii, N.mucosa and V.parvula, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Filifactor alocis, Dialister pneumosintes, Selenonomas sputigena, Selenominas noxia, Catonella morbi, Parvimonas micra and Tannerella forsythia) communities with metatranscriptomics, targeted proteomics and fluorescent microscopy, we demonstrate that smoke exposure significantly downregulates essential metabolic functions within commensal biofilms, while significantly increasing expression of virulence genes, notably lipopolysaccharide (LPS), flagella and capsule synthesis. By contrast, in pathogen-rich biofilms several metabolic pathways were over-expressed in response to smoke exposure. Under smoke-rich conditions, epithelial cells mounted an early and amplified pro-inflammatory and oxidative stress response to these virulence-enhanced commensal biofilms, and a muted early response to pathogen-rich biofilms. Commensal biofilms also demonstrated early and widespread cell death. Similar results were observed when smoke-free epithelial cells were challenged with smoke-conditioned biofilms, but not vice versa. In conclusion, our data suggest that smoke-induced transcriptional shifts in commensal biofilms triggers a florid pro-inflammatory response, leading to early commensal death, which may preclude niche saturation by these beneficial organisms. The cytokine-rich, pro-oxidant, anaerobic environment sustains inflammophilic bacteria, and, in the absence of commensal antagonism, may promote the creation of pathogen-rich biofilms in smokers.

Tobacco: How smoking promotes harmful biofilms

Tobacco smoke inhibits the metabolism of beneficial bacteria in biofilms, while activating specific genes in pathogenic bacteria. This suggests a mechanism to explain how smoking quickly leads to the formation of damaging biofilms in the mouth and respiratory tract. Purnima Kumar and colleagues at Ohio State University, USA studied the effect of tobacco smoke on cultured biofilms used to model those that form on mucous membranes. They detected specific and varied changes in the activity of genes, proteins and metabolism that allowed pathogenic bacteria to displace beneficial “commensal” bacteria. The research suggests the transition toward pathogen-rich biofilms may contribute to the health effects of smoking by causing increased inflammation of mucous membranes and the production of damaging oxidant chemicals. Further research should investigate the chemical constituents of smoke responsible for these effects.

Introduction

It is well known that an intact epithelial barrier plays a critical role in maintaining the health of mucosal surfaces, both by preventing ingress of bacteria and by secreting immuno-modulatory signaling molecules.1,2 Evidence is now emerging that host-associated bacterial biofilms play a similarly important role in maintaining mucosal health.3,4 Commensal bacteria prevent pathogen colonization in different habitats by saturating these niches and educating the immune system to differentiate between “friend and foe”. A biofilm that elicits a low immune response is seen by the epithelium as health-compatible and as pathogenic when it has a high antigenic load.5–7 Equilibrium between these biofilms and the host immune system is a determinant of health. Disease occurs when the ecosystem is disrupted and triggers a florid host response.8–10 For example, in the oral cavity, it has been established that dysbiotic microbial biofilms underlie the etiologies of oral cancer, caries, and periodontal diseases.11–15

Smokers are at especially high risk for oral cancer and periodontitis, with a 16-fold increase in odds for developing extensive and severe disease when compared to nonsmokers.16 We have previously demonstrated that smokers not only have pathogen-rich, commensal-poor biofilms in disease, but also that this dysbiosis is established long before the onset of clinical disease.17,18 Moreover, this pathogen enrichment occurs very early during the colonization of the biofilm.19 However, the mechanism underlying the commensal clearance and pathogen acquisition in this high-risk group is not known. Evidence indicates that loss of commensal-rich biofilms decreases the protection offered by them and hence increases susceptibility to disease in the gut, nasopharynx and vagina.20,21 Therefore, it is critical to understand the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms that influence bacterial community assembly in smokers.

Bacterial colonization of biofilms depends on both inter-bacterial and host–bacterial interactions, and evidence is now emerging that the epithelial cells play an active role in assembling mucosa-associated biofilms and in determining their composition.22 Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain this role of epithelial cells: expression of surface receptors, secretion of immunomodulatory molecules and provision of nutrients.10,23 It is known that smoking alters the phenotype of epithelial cells by affecting immune expression and oxidative stress;24,25 it is possible that this may be a possible mechanism by which smoking contributes to altered biofilm colonization. Hence, we sought to explore the effect of smoking on oral host–bacterial interactions, using a mucosal–microbial interface model to mimic the subgingival environment.

Results

‘MiMIC’ry

We initially investigated the ability of microbial–mucosal interface construct (MiMIC) to recapitulate the subgingival epithelial–microbial interface. Visually, the in vitro biofilms demonstrated characteristics similar to those previously described in vivo subgingival biofilms,26 with a multi-layered structure, fibril-mediated coaggregation between colonizers, channel-like structures separating the micro-colonies, and a sequential overlaying of the secondary colonizers (bacillary, cocco-bacillary shapes) over the primary colonizers (cocci) (Supplemental Fig. 1a i, ii). Compositionally, the abundances of the specific species in the biofilms were similar to those reported from in vivo biofilms in periodontal health and disease27,28 (Supplemental Fig. 1b). The immune mediators secreted by the epithelial monolayer also demonstrated significantly different concentrations when challenged with the commensal or pathogen-rich biofilms (Supplemental Fig. 1c). The concentrations of these mediators were comparable to those previously observed in periodontal health and disease.29

Host–bacterial interactions

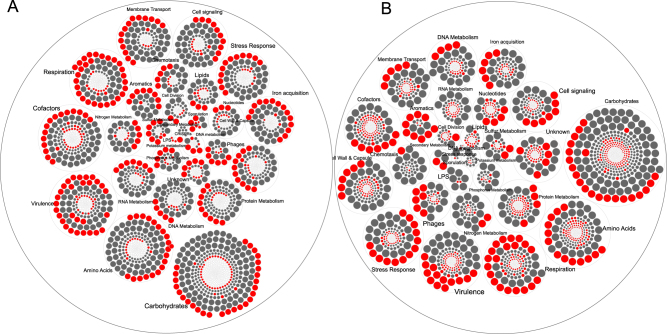

Exposure to cigarettes smoke led to downregulation of 1465 genes belonging to 459 functional families and upregulation of 469 genes contributing to 88 functions in commensals (Fig. 1 and Supplemental Table 1). By contrast, in pathogen-rich biofilms, smoke conditioning led to downregulation of 1058 genes (corresponding to 249 functions) and upregulation of 1497 genes that contributed to 252 functions. In commensal biofilms, significant downregulation of genes relating to basic metabolic pathways (carbohydrate, protein, DNA and RNA metabolisms, respiration, stress response and membrane transport) and upregulation of certain virulence (LPS, flagella and capsule synthesis) and fermentative pathways were observed. In pathogen-rich communities, smoke exposure downregulated genes contributing to aerobic carbohydrate metabolism, LPS, flagella and upregulated fermentative pathways, stress response and iron acquisition.

Fig. 1.

Hierarchical circle packing plot of transcriptional activity in commensal (a) and pathogen-rich (b) biofilms. Each circle represents a gene and is sized by log2 fold change. Genes are grouped based on their functional roles based on SEED classification. Genes that were significantly over-expressed (log2 fold change >2, p < 0.05, FDR-adjusted Wald test) in a smoke-rich environment when compared to controls are in red, while those that were under-expressed following smoke conditioning are shown in gray. White circles indicate genes whose change in expression did not meet the above criteria. The data used in creating this Figure are shown in Supplementary Table 1

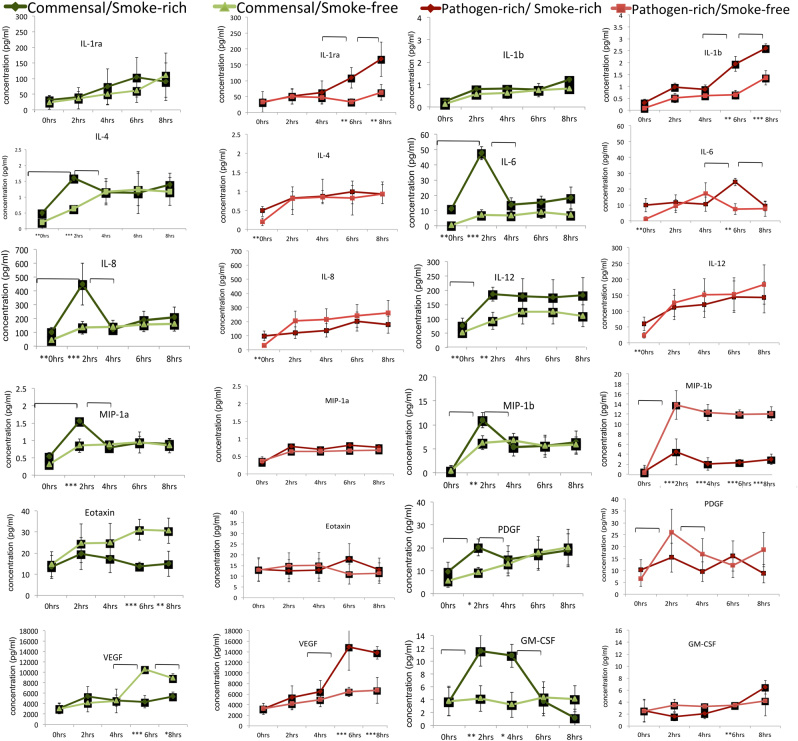

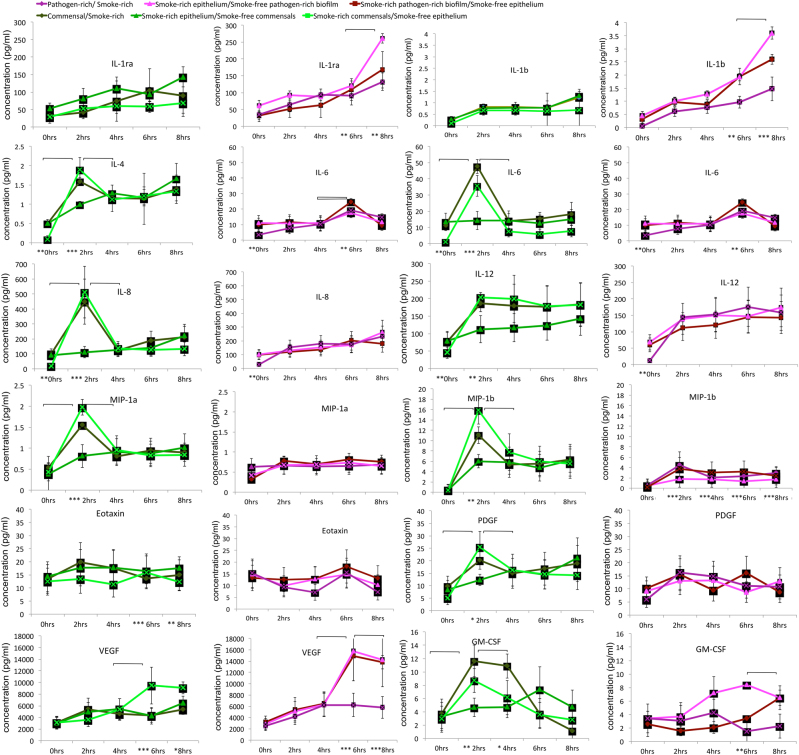

We then examined the responses of the epithelial cells to these commensal and pathogen-rich biofilms at 2,4,6 and 8 h in smoke-free and smoke-rich environments (Fig. 2). Early (2 h) increases in IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, GM-CSF, MIP-1α, MIP-1β and PDGF and late (6 and 8 h) decreases in Eotaxin and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) were observed in response to commensal biofilms in a smoke-rich environment (p < 0.05, repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA)). Smoke conditioning also led to late (6 and 8 h) increases in IL-1β, IL-6 and VEGF and sustained decrease in MIP-1b response to pathogen-rich biofilms. Since cytokine production can be impacted both by the type of bacterial challenge as well as smoke exposure, we then investigated if these effects were attributable to a smoke-induced hyper-inflammatory response or to a bacterial challenge or to both. When the MiMIC was recreated using either smoke-conditioned biofilm or epithelium (i.e., smoke-conditioned epithelium challenged with smoke-free biofilms and vice versa), it was seen that the responses of smoke-free epithelium to smoke-rich commensal biofilms were significantly similar to those of the smoke-rich overall environment with respect to several inflammatory mediators (p < 0.05, ANOVA, Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Cytokine released by OKF6-TERT cells in response to biofilm challenge. Levels of selected cytokines in response to commensal (greens) and pathogen-rich (reds) biofilms in smoke-free and smoke-rich environments are shown. Data represent means of six replicates, with standard deviation bars. (* p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, between-group differences, brackets represent p < 0.01, repeated measures ANOVA)

Fig. 3.

Cytokine released by smoke-conditioned OKF6-TERT cells in response to smoke-conditioned and smoke-free biofilm challenge. Levels of selected cytokines in response to commensal (greens) and pathogen-rich (reds) biofilms in smoke-free and smoke-rich environments are shown. Data represent means of six replicates, with standard deviation bars. (* p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, between-group differences, brackets represent p < 0.01, repeated measures ANOVA)

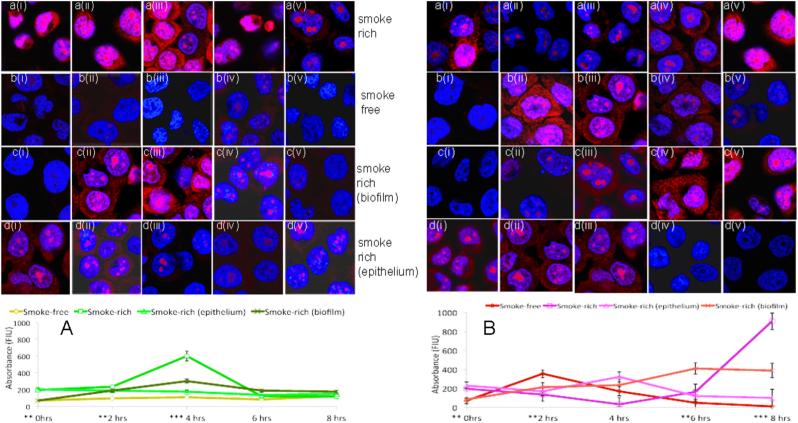

Smoke exposure, by itself, led to a higher reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation by epithelial in the absence of a bacterial challenge (0 h, Fig. 4). There was also a significantly greater ROS response to commensal biofilms at 2 and 4 h in a smoke-rich environment. Moreover, this increase was evident when smoke-free epithelial cells were challenged with smoke-rich commensal biofilms. On the other hand, epithelial cells responded with significantly greater ROS generation at 2 h in response to pathogens in a smoke-free environment. However, in a smoke-rich environment, this response was delayed to 8 h (p < 0.05, repeated measures ANOVA).

Fig. 4.

Intracellular ROS production in response to commensal and pathogen-rich biofilms in smoke-free and smoke-rich environments. Figure 4a shows ROS production in response to commensal biofilm challenge, while Fig. 4b shows ROS production in response to pathogen biofilm challenge. Data represent means of six replicates, with standard deviation bars. i–v indicate sample micrographs at 0, 2, 4, 6 and 8 h respectively, while a–d indicates the environment at the same time points (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, repeated measures ANOVA)

Since both transcriptional and proteomic activity depend on live cells, we measured viability bacterial biofilms and epithelial cells over the 8-h period at different concentrations of cigarette smoke extract (CSE). Commensal biofilms demonstrated a 20% loss in viability at 2 h, 50% at 8 h (p < 0.05, repeated measures ANOVA, Supplemental Fig. 2a). This was observed for all concentrations of CSE (all-or-none pattern). Pathogen-rich biofilms, on the other hand, demonstrated a dose response in viability, with 2 and 5% CSE leading to a significant decrease in viability at 8 h when compared to the lower concentrations (p < 0.05, repeated measures ANOVA, Supplemental Fig. 2b). Pathogen biofilms did not demonstrate a significant loss of viability in 1% CSE during the 8-h observation period. There was no significant loss of epithelial viability during the observation period with any concentration of CSE (Supplemental Fig. 2c, d).

Previous investigations have used single bacterial species to examine host–bacterial interactions.30–32 To test the hypothesis that single species can be used as surrogates for multi-species biofilms, Streptococcus mitis biofilms were compared to the multi-species commensal biofilms, while P. gingivalis biofilms were compared to multi-species pathogen-rich biofilms (Supplemental Fig. 3). The responses of single species were significantly different from the multi-species biofilms. Greater cytokine responses (notably IL-1B, IL-4, IL-6, PDGF, MIP-1B, GM-CSF) were observed at later time points (6 and 8 h) to P.gingivalis biofilms when compared to multi-species biofilms both in the presence and absence of smoke. Cytokine responses to S.mitis biofilms did not demonstrate a consistent pattern when compared to multi-species commensal biofilms either in the presence or absence of smoke.

Discussion

This study sought to investigate the mechanism by which smoking creates commensal-poor, pathogen-rich communities in different mucosal niches. Although the oral cavity is one of the most accessible ecosystems in the human body, there are several difficulties associated with studying this process in vivo. Repeatedly sampling the same site over short spans of time alters the quality and quantity of the plaque biofilm and gingival crevicular fluid, and the results may not accurately reflect host–bacterial interactions. Hence, an in vitro model of the microbial–mucosal interface was used in this study to overcome these issues. This is a modification of the original Zurich 10-species model,33–36 and the present investigation attests to the versatility of the model in allowing the incorporation of customized bacterial consortia into the biofilm. We acknowledge that is a highly simplified model, and does not fully replicate the intricate dynamics between a polymicrobial biofilm and a complex multi-cellular immuno-inflammatory apparatus, however, our data demonstrates that it recapitulates the functional profiles of the subgingival biofilm, as well as the innate immune responses of the sulcular epithelium. Recent studies using proteomics and transcriptomics of fibroblastic responses to these biofilms also serve to validate the ability of this system to mimic events in the subgingival sulcus.36,37

The time points selected were based on evidence that innate immune responses occur within 6–8 h of bacterial colonization,38 as well as on the sequence of bacterial colonization described by Diaz et al, with initial colonization beginning at 2 h and a climax community at 8 h.39 Also, preliminary studies revealed greater than 25% loss of viability of eukaryotic cells following a 12-h pathogen challenge or 24-h smoke exposure. One percent CSE was used to test the effect of smoking because the contents of the CSE produced in this setting reflect the plasma nicotine concentrations of 10-pack year smokers.40,41 Previous investigations have reported that the nutritional conditions within the MiMIC affect the transcriptional activity of the cells.33 In the present investigation, while it is possible that the nutritional environment created by the media may be responsible for some of the transcriptional and proteomic readouts, however, since the conditions were the same across groups, the effects are comparable.

Epithelial cells are the first responders to bacterial presence in all mucosal niches; they are part of an innate immune apparatus that secretes chemo-attractive molecules to initiate an inflammatory response.1,42 The cross talk between oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory immune response plays a critical role in the initiation and progression of several diseases. More importantly, oxidative stress plays a major role in the pathogenesis of smoking-related diseases.43 Since virtually nothing is known about oxidative stress responses to commensal and pathogenic bacterial communities, we investigated the ability of these biofilms to induce intra-cellular ROS.

Our results demonstrate that under normal circumstances, the inflammatory and stress responses to a commensal biofilm are more muted than to a pathogen-rich community. The commensal biofilms also elicited high levels of IL-10 from the epithelial cells. Evidence from in vivo studies indicates that commensals suppress TLR4 activation through the IL-10 pathway.8 Thus, our results are in line with several studies that demonstrate a differential cytokine expression to pathogenic and non-pathogenic triggers5,44,45 and serve to validate the present study.

By contrast, in a smoke-rich environment, epithelial cells mounted a robust and early pro-inflammatory response to commensal biofilms (Figs. 2 and 3). This was also seen in the amount of ROS generated by the epithelial cells (Fig. 4a). The early response to pathogen-rich biofilms, by comparison, was highly subdued. These findings corroborate several lines of evidence in the literature suggesting that the innate immune response to pathogens is abrogated in smokers.24,46 Since dead bacteria are incapable of producing an important recognition molecule, vita-PAMP (viability-associated pathogen-associated molecular patterns), they elicit a significantly lower innate immune response.47 In order to investigate if this dampened response to pathogens was caused by cellular death, we examined both biofilm and epithelial viability over the duration of the study. Surprisingly, smoke-treated commensals, and not pathogens, demonstrated an early and significant loss of viability. This commensal death was observed following the inflammatory and pro-oxidant surge at 2 h. In the oral ecosystem, niche saturation by pioneer organisms plays an important role in creating colonization resistance to pathogens. It is possible that this early commensal death affects downstream events in biofilm formation, and may play a central role in creating the pathogen enrichment that was previously reported by our group and others.

In the present investigation, smoke-conditioned epithelium secreted greater amounts of pro-inflammatory mediators even prior to bacterial challenge (0 h, Fig. 2), corroborating previous evidence that smoking constitutively increases immune responses in these cells.48,49 Since epithelial cells play an important role in acquiring and assembling mucosal microbial communities, we used two approaches to investigate the importance of this constitutive inflammation on commensal depletion. Initially, we challenged smoke-conditioned epithelial cells with smoke-free biofilms and vice versa (Fig. 2). The immune responses of smoke-free epithelial cells to smoke-conditioned commensal biofilms closely mimicked those of the smoke-rich overall environment, suggesting that the effects of smoking on the microbiome contribute largely to its detrimental effects on host–bacterial interactions. To investigate what these effects on the biofilm are, we examined the effects of smoking on gene expression within commensal and pathogen-rich biofilms. The most striking functional shift was a downregulation of primary metabolic functions within commensal biofilms and upregulation in pathogen-rich communities following 2 h of smoke conditioning. Importantly, fermentative pathways for energy acquisition were upregulated in both biofilms. We have previously demonstrated that energy efficiency is a central hallmark of health-compatible biofilms.50 Fermentation yields several short chain fatty acids (SCFA) such as butyrate, propionate and isobutyrate, which impair epithelial cell functions51 while increasing apoptosis and necrosis.52 These SCFAs have also been strongly associated with periodontitis.53,54 In vivo, such alterations in primary metabolic pathways could have important implications for metabolic partnerships and the development of the climax microbial community.

Glutathione is an important redox-buffering compound that protects bacterial cells from osmotic stress, electrophiles and oxidative stress by scavenging reactive oxygen.55,56 The present investigation demonstrates a marked reduction in glutathione mediated stress response in commensals, but not pathogens following smoke exposure (Supplemental Table 1). In the presence of amplified ROS expression by epithelial cells, this diminished capability can only be detrimental to commensal survival in smokers.

Iron is important for bacterial survival since it facilitates electron transport, nucleotide synthesis, peroxide reduction and other essential cellular functions. Iron-deprivation leads to expression of several outer membrane proteins, siderophores, hemolysins and toxins, while availability of iron promotes pathogen expansion and cellular invasion.57–59 Smoke exposure severely impaired iron acquisition and transport in commensals, and upregulated it in pathogen-rich biofilms. This has important implications for disease, since this might be a contributing factor for tissue invasion of bacteria that has been reported in disease.

Previous studies examining the proteins secreted by gingival epithelial cells in response to pathogen-rich biofilms, especially those populated by red-complex bacteria; have demonstrated a pronounced pro-inflammatory response to these biofilms.60,61 One molecule that is common to these red-complex species is Lipid-A, the lipid moiety of LPS, a powerful antigen that elicits a florid pro-inflammatory host response.62 Lipid-A synthesis was upregulated in commensal and downregulated in pathogen-rich biofilms conditioned with smoke. This would partly serve to explain the early, exaggerated pro-inflammatory response to commensals and a muted response to pathogen-rich communities in the presence of smoke.

Based on our findings, we propose a model to explain the formation of commensal-poor, pathogen-rich communities in smokers. Normally, biofilm formation begins as a community dominated by commensals63; and this niche saturation prevents pathogen colonization.64,65 Pathogen colonization is also controlled by host immune system recognition of virulence patterns.66 In smokers, a transcriptional shift in the commensal biofilms towards higher virulence combined with a constitutively greater cytokine production triggers a florid pro-inflammatory response from the epithelial cells, leading to early commensal death; and hence precluding niche saturation by these beneficial organisms. On the other hand, in the presence of smoke, these very same virulence signatures are dampened in pathogen-rich biofilms in the early stages, thereby creating a “Trojan Horse”, which the host immune system fails to recognize. Oral pathogens normally thrive in anaerobic, reducing environments; the early pro-inflammatory and oxidative stress response in smokers, along with absence of commensal antagonism, leads to large-scale pathogen colonization, which is fueled and sustained by the florid pro-inflammatory response. The resulting cyclical chain of host-microbe interaction events may ultimately lead to disease.

It is not apparent from this study which of the constituents of cigarette smoke is responsible for the observed effects. The relative contributions of the gaseous and liquid phases of the smoke, as well as the individual constituents, merits further study, especially in light of the fact that electronic nicotine delivery systems, or e-cigs are rapidly gaining popularity among younger smokers.

Materials and methods

Microbial–mucosal interface construct (MiMIC)

Cryo-preserved second passage TERT-immortalized human oral keratinocytes (OKF6/TERT-2, purchased from Jim Rheinwald’s laboratory67) were thawed and cultured in keratinocyte serum-free medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), supplemented with 25 µg/mL of bovine pituitary extract (BPE), 0.2 ng/mL of epidermal growth factor (EGF), 0.3 mM calcium chloride, 100 units/mL penicillin G and 100 µg/mL streptomycin].67 Cells were seeded into 6-well Costar tissue culture plates and grown to confluence in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium-F12 (1:1, vol:vol) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Ca, USA) supplemented with 0.2 ng/mL EGF, 25 µg/mL BPE, 1.5 mM L-glutamine, [100 units/mL penicillin G and 100 µg/mL streptomycin] in 5% CO2 in air at 37 °C. Prior to biofilm challenge, the test group of cells was conditioned with CSE for 24 h as described below.

Biofilms were developed using the protocol established by Guggenheim et al.35 and modified later for subgingival biofilms.68,69 Briefly, sterilized, sintered hydroxyapatite discs (Clarkson Chromatography Products, South Williamsport, PA) were incubated in artificial saliva for 24 h to establish a pellicle coat, following which multi-species commensal biofilms were generated by seeding six pioneer species (Streptococcus oralis, Streptococcus sanguis, Streptococcus mitis, Actinomyces naeslundii, Neisseria mucosa and Veillonella parvula) and incubating under aerobic conditions in a 1:1(vol:vol) mixture of brain–heart Infusion broth (BHI) and artificial saliva. These organisms were selected based on data from our own and Kolenbrander’s work demonstrating their predominance in health-compatible microbiomes.63 Pathogen-rich biofilms were created by further seeding the commensal biofilms with an intermediate colonizer (Fusobacterium nucleatum), followed 24 h later by Porphyromonas gingivalis, Filifactor alocis, Dialister pneumosintes, Selenonomas sputigena, Selenominas noxia, Catonella morbi, Parvimonas micra and Tannerella forsythia and incubating under anaerobic conditions for a further 24 h.

The biofilms were overlaid on the OKF6 cells with a 1-mm separation to mimic the microbial–mucosal interface. This was achieved by using 1-mm thick O-rings to separate the discs from the epithelium. Immediately prior to the overlay, spent tissue culture medium was replaced with fresh medium (either with or without CSE, as appropriate). The overlay was incubated in 5% CO2 in air at 37 °C for the appropriate time periods.

Cigarette smoke extraction and conditioning the MiMIC

CSE was prepared immediately before use by bubbling smoke from two 3R4F research cigarettes (9.4 mg tar/0.726 mg nicotine, University of Kentucky) into 20 ml of serum-free KER-SFM and 20 ml of BHI. To maintain consistency of CSE between experiments, optical density measurements were taken at 320 nm, with an optical density of 0.65 representing 100% CSE.70 The CSE was diluted to 1% with either BHI or KER-SFM, and the MiMIC conditioned with 1% CSE for 24 h. A volume of 100 μL of the culture medium was aspirated at 2, 4, 6 and 8 h and frozen at −20 °C until further analysis.

Metatranscriptomics

Total RNA was isolated from the biofilms using the mirVana miRNA isolation kit (Applied Biosystems). Microbial cells were lysed and RNA was extracted by Acid-Phenol: Chloroform and ethanol precipitation and eluted in nuclease-free water. Ribosomal RNA was depleted and mRNA enriched by modified capture hybridization approach. Enriched mRNA served as a template for the polyadenylation reaction and cDNA synthesis. Microbial libraries were clustered on the Illumina HiSeq platform, and 150 bp paired-end sequencing was performed. The Illumina base-calling pipeline was used to process the raw fluorescence images and call sequences. Raw reads with >10% unknown nucleotides or with >50% low quality nucleotides (quality value < 20) were discarded. Microbial transcripts were quality filtered using SolexaQA++, and aligned against the Human Oral Microbiome Database71 using DIAMOND.72 Aligned sequences were annotated to the KEGG database using Megan 6.73 The metagenomic sequence classifier Kraken74 was used along with our custom tool, kraken-biom, for taxonomic identification. Analysis and visualization of the distribution of operational taxonomic units was performed using QIIME75 and PhyloToAST.76 Bioconductor package for R, DESeq2, was used to perform differential expression analysis of the annotated microbial transcripts.

Data availability

All sequences are located in the servers of Argonne National Lab (MG-RAST) and relevant data are available from the authors.

Cytokine assay

Cytokine analysis was done using a commercially available multiplexed bead-based immunoassay designed to quantitate multiple cytokines.77 A panel of 27 cytokines was selected, including Th1 and Th2 cytokines (Interleukin-2 (IL2), Interleukin-12 (IL12), Interferon-γ (INF-γ), Interleukin-1ra (IL-1ra), pro-inflammatory cytokines (Interleukin-1β (IL-1β), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF)), chemokines (Interleukin-8 (IL-8), interferon gamma-induced protein 10, monocyte chemotactic protein-1, macrophage inflammatory proteins (MIP-1α and MIP-1β), regulated on activation, normal T expressed and secreted and Eotaxin), regulators of T-cells and natural killer cells (interleukin-7 (IL-7) and interleukin-15 (IL-15)), and growth factors (VEGF, plasma-derived growth factor (PDGF)). Briefly, 27 distinct sets of fluorescently dyed beads (Bio-rad laboratories, Inc, Hercules, CA) were conjugated with monoclonal antibodies specific for each cytokine and incubated with 50 μL of supernatant. Biotinylated detection antibody (25 μL) and Streptavidin-phycoerythrin reporter (50 μL) were added sequentially. The level of each cytokine was analyzed by measuring the fluorescence of each bead type as well as the fluorescent signal from the reporter on a Bio-Plex 200 flow cytometric detection system.

Bacterial viability

Bacterial viability was measured using a BacLight kit (Life Technologies, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the biofilms were incubated in 1.5 mL of 0.3% SYTO 9® and propidium iodide and the fluorescence measured at 486 and 520 nm using a Spectral FlowView confocal microscope at ×10 magnification. The ratio of green to red fluorescence was computed and used to determine bacterial viability.

Epithelial viability

The viability of OKF6-TERT cells was measured using a commercially available lactate dehydrogenase assay (CytoTox-ONE, Promega Corporation, Madison, WI). A volume of 100 μL of the supplied reagent was added to the culture plates with the cells and incubated at 22 °C for 10 min. The reaction was terminated by adding 50 μL of the Stop Solution, and the fluorescence was measured using a fluorometer with an excitation wavelength of 560 nm and an emission wavelength of 590 nm. Positive controls were cells that had been lyzed by freeze-thaw cycles. Cell viability was measured as the ratio of fluorescence between freeze-thaw lyzed (dead) cells and the test groups.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS)

The level of intracellular superoxide production in OKF6/TERT2 keratinocytes was measured using dihydroethidium (DHE)-derived fluorescence as previously described.78 Cells were grown on coverslips in 24-well plates, conditioned with CSE and challenged with biofilms as described earlier. Thirty minutes prior to the allocated time point, 10 μM DHE and 1 μM of Hoescht 33342 (nuclear stain) were added and incubated. At the indicated time points, cells were washed three times with 1× PBS and immediately viewed with an Olympus Spectral FlowView microscope using a ×60 objective, at 405 and 543 nm excitations. Fluorescence intensity, which positively correlates with the amount of O2 − generation, was measured. High-resolution images were obtained using constant exposure time. A single scan of a new field was used to limit any change in intensity caused by overexposure. The remaining signal in the presence of SOD mimetic Mn(III)tetrakis(4-benzoic acid)porphyrin chloride (MnTBAP) (Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA) was considered to be non-specific (background signal), and therefore was subtracted from all other mean intensities in controls. The fluorescence intensity was quantified using Olympus software. The mean intensity of the fluorescence in a low power field was used for comparison between the groups.

Statistical analysis

All reactions were carried out in triplicate and assays duplicated. Bioconductor package for R, DESeq2, was used to perform differential expression analysis of the annotated microbial transcripts. Phylogenetic trees were visualized using PhyloToAST76 and iTol.79 Within and between-group comparisons of cytokines and ROS were made using Repeated Measures ANOVA (Tukey HSD) in a Generalized Estimating Equations framework. All analyses were carried out using JMP (Cary, NC) and graphed using the capabilities of R and VORTEX (http://webapp-kumarlab.rhcloud.com/ 80).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIDCR grant R01 DE022579.

Author contributions

S.A.S. conducted all the experiments; S.V. designed and supervised the reactive oxygen species experiments, J.D.W. designed and supervised the mucosal cell-line challenge experiments, S.M.G. was responsible for the metatranscriptomic analysis, S.M.D. was responsible for all bioinformatics pipelines, P.S.K. was responsible for overall study design, designed and supervised the bacterial biofilm experiments and the cytokine assays. All authors participated equally in data analysis, interpretation of results and manuscript preparation.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies the paper on the npj Biofilms and Microbiomes website (10.1038/s41522-017-0033-2).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bosshardt DD, Lang NP. The junctional epithelium: from health to disease. J. Dent. Res. 2005;84:9–20. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hooper LV, Gordon JI. Commensal host-bacterial relationships in the gut. Science. 2001;292:1115–1118. doi: 10.1126/science.1058709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hooper LV, et al. Molecular analysis of commensal host-microbial relationships in the intestine. Science. 2001;291:881–884. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5505.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Human Microbiome Project Consortium Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012;486:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hasegawa Y, et al. Gingival epithelial cell transcriptional responses to commensal and opportunistic oral microbial species. Infect. Immun. 2007;75:2540–2547. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01957-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rakoff-Nahoum S, et al. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Page RC, Schroeder HE. Pathogenesis of inflammatory periodontal disease. A summary of current work. Lab. Invest. 1976;34:235–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanoue T, Umesaki Y, Honda K. Immune responses to gut microbiota-commensals and pathogens. Gut Microbes. 2010;1:224–233. doi: 10.4161/gmic.1.4.12613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darveau RP, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide contains multiple lipid A species that functionally interact with both toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:5041–5051. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5041-5051.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darveau RP, Tanner A, Page RC. The microbial challenge in periodontitis. Periodontol. 2000. 1997;14:12–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar PS, Griffen AL, Moeschberger ML, Leys EJ. Identification of candidate periodontal pathogens and beneficial species by quantitative 16S clonal analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43:3944–3955. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.8.3944-3955.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hajishengallis G, Lamont RJ. Beyond the red complex and into more complexity: the polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis (PSD) model of periodontal disease etiology. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2012;27:409–419. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2012.00663.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiao Y, Hasegawa M, Inohara N. The role of oral pathobionts in dysbiosis during periodontitis development. J. Dent. Res. 2014;93:539–546. doi: 10.1177/0022034514528212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hooper SJ, et al. Viable bacteria present within oral squamous cell carcinoma tissue. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006;44:1719–1725. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.5.1719-1725.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loesche, W. J. Dental Caries: A Treatable Infection. (Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, Illinois, 1982).

- 16.Tomar SL, Asma S. Smoking-attributable periodontitis in the United States: findings from NHANES III. national health and nutrition examination survey. J. Periodontol. 2000;71:743–751. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.5.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mason MR, et al. The subgingival microbiome of clinically healthy current and never smokers. Isme J. 2015;9:268–272. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shchipkova A, Nagaraja Y. H., N & Kumar, P., S. Subgingival microbial profiles in smokers with periodontitis. J. Dent. Res. 2010;89:1247–1253. doi: 10.1177/0022034510377203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar PS, et al. Tobacco smoking affects bacterial acquisition and colonization in oral biofilms. Infect. Immun. 2011;79:4730–4738. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05371-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mirmonsef P, et al. The effects of commensal bacteria on innate immune responses in the female genital tract. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2011;65:190–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00943.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tlaskalova-Hogenova H, et al. Commensal bacteria (normal microflora), mucosal immunity and chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Immunol. Lett. 2004;93:97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SM, et al. Bacterial colonization factors control specificity and stability of the gut microbiota. Nature. 2013;501:426–429. doi: 10.1038/nature12447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Artis D. Epithelial-cell recognition of commensal bacteria and maintenance of immune homeostasis in the gut. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:411–420. doi: 10.1038/nri2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dye JA, Adler KB. Effects of cigarette smoke on epithelial cells of the respiratory tract. Thorax. 1994;49:825–834. doi: 10.1136/thx.49.8.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kulkarni R, et al. Cigarette smoke inhibits airway epithelial cell innate immune responses to bacteria. Infect. Immun. 2010;78:2146–2152. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01410-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takeuchi H, Yamanaka Y, Yamamoto K. Morphological analysis of subgingival biofilm formation on synthetic carbonate apatite inserted into human periodontal pockets. Aust. Dent. J. 2004;49:72–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2004.tb00053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar PS, Griffen AL, Moeschberger ML, Leys EJ. Identification of candidate periodontal pathogens and benficial species using quantitative 16S clonal analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43:3944–3955. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.8.3944-3955.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar PS, et al. Tobacco smoking affects bacterial acquisition and colonization in oral biofilms. Infect. Immun. 2011;79:4730–4738. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05371-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar PS, et al. Tobacco smoking affects bacterial acquisition and colonization in oral biofilms. Infect. Immun. 2011;79:4730–4738. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05371-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han YW, et al. Interactions between periodontal bacteria and human oral epithelial cells: Fusobacterium nucleatum adheres to and invades epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:3140–3146. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.6.3140-3146.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krisanaprakornkit S, et al. Inducible expression of human beta-defensin 2 by Fusobacterium nucleatum in oral epithelial cells: multiple signaling pathways and role of commensal bacteria in innate immunity and the epithelial barrier. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:2907–2915. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.5.2907-2915.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kesavalu L, Ebersole JL, Machen RL, Holt SC. Porphyromonas gingivalis virulence in mice: induction of immunity to bacterial components. Infect. Immun. 1992;60:1455–1464. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1455-1464.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ammann TW, Gmür R, Thurnheer T. Advancement of the 10-species subgingival Zurich Biofilm model by examining different nutritional conditions and defining the structure of the in vitrobiofilms. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:227. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guggenheim, B. et al. In vitro modeling of host-parasite interactions: the ‘subgingival’ biofilm challenge of primary human epithelial cells. BMC Microbiol. 10.1186/1471-2180-9-280 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Guggenheim B, et al. In vitro modeling of host-parasite interactions: the’subgingival’biofilm challenge of primary human epithelial cells. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:280. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belibasakis GN, Bao K, Bostanci N. Transcriptional profiling of human gingival fibroblasts in response to multi-species in vitro subgingival biofilms. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2014;29:174–183. doi: 10.1111/omi.12053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bao K, et al. Proteomic profiling of host-biofilm interactions in an oral infection model resembling the periodontal pocket. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:15999. doi: 10.1038/srep15999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Janeway, C., Travers, P., Walport, M. & Shlomick, M. Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease. (Garland Science, UK, 2004).

- 39.Diaz PI, et al. Molecular characterization of subject-specific oral microflora during initial colonization of enamel. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:2837–2848. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2837-2848.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bernhard D, et al. Disruption of vascular endothelial homeostasis by tobacco smoke: impact on atherosclerosis. FASEB J. 2003;17:2302–2304. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0312fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zuccaro P, et al. Determination of nicotine and four metabolites in the serum of smokers by high-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection. J. Chromatogr. 1993;621:257–261. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(93)80103-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weinberg A, Krisanaprakornkit S, Dale BA. Epithelial antimicrobial peptides: review and significance for oral applications. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 1998;9:399–414. doi: 10.1177/10454411980090040201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MacNee W, Rahman I. Is oxidative stress central to the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Trends Mol. Med. 2001;7:55–62. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4914(01)01912-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haller D, et al. Non-pathogenic bacteria elicit a differential cytokine response by intestinal epithelial cell/leucocyte co-cultures. Gut. 2000;47:79–87. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goto Y, Ivanov II. Intestinal epithelial cells as mediators of the commensal-host immune crosstalk. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2013;91:204–214. doi: 10.1038/icb.2012.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kulkarni R, et al. Cigarette smoke inhibits airway epithelial cell innate immune responses to bacteria. Infect. Immun. 2010;78:2146–2152. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01410-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mourao-Sa D, Roy S, Blander JM. Vita-PAMPs: signatures of microbial viability. Adv. Exp. Medi. Biol. 2013;785:1–8. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-6217-0_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mio T, et al. Cigarette smoke induces interleukin-8 release from human bronchial epithelial cells. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 1997;155:1770–1776. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.5.9154890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van der Vaart H, Postma D, Timens W, Ten Hacken N. Acute effects of cigarette smoke on inflammation and oxidative stress: a review. Thorax. 2004;59:713–721. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.012468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dabdoub SM, Ganesan SM, Kumar PS. Comparative metagenomics reveals taxonomically idiosyncratic yet functionally congruent communities in periodontitis. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:38993. doi: 10.1038/srep38993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pollanen MT, Salonen JI. Effect of short chain fatty acids on human gingival epithelial cell keratins in vitro. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2000;108:523–529. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2000.00881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sorkin BC, Niederman R. Short chain carboxylic acids decrease human gingival keratinocyte proliferation and increase apoptosis and necrosis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1998;25:311–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.1998.tb02446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Loesche WJ, Grossman NS. Periodontal disease as a specific, albeit chronic, infection: diagnosis and treatment. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2001;14:727–752. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.4.727-752.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Niederman R, Zhang J, Kashket S. Short-chain carboxylic-acid-stimulated, PMN-mediated gingival inflammation. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 1997;8:269–290. doi: 10.1177/10454411970080030301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kulkarni R, et al. Cigarette smoke increases Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation via oxidative stress. Infect. Immun. 2012;80:3804–3811. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00689-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mydel P, et al. Roles of the host oxidative immune response and bacterial antioxidant rubrerythrin during Porphyromonas gingivalis infection. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e76. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Al-Qutub MN, et al. Hemin-dependent modulation of the lipid A structure of Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:4474–4485. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01924-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weinberg ED. Microbial pathogens with impaired ability to acquire host iron. Biometals. 2000;13:85–89. doi: 10.1023/A:1009293500209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weinberg ED. Iron availability and infection. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1790:600–605. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bostanci N, et al. Secretome of gingival epithelium in response to subgingival biofilms. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2015;30:323–335. doi: 10.1111/omi.12096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bao K, et al. Quantitative proteomics reveal distinct protein regulations caused by aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans within subgingival biofilms. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rangarajan M, et al. Identification of a second lipopolysaccharide in Porphyromonas gingivalis W50. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:2920–2932. doi: 10.1128/JB.01868-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kolenbrander PE, et al. Bacterial interactions and successions during plaque development. Periodontol. 2000. 2006;42:47–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2006.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marsh PD, Percival RS. The oral microflora--friend or foe? Can we decide? Int. Dent. J. 2006;56:233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2006.tb00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stingu CS, et al. Periodontitis is associated with a loss of colonization by Streptococcus sanguinis. J. Med. Microbiol. 2008;57:495–499. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47649-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reddick LE, Alto NM. Bacteria fighting back: how pathogens target and subvert the host innate immune system. Mol. Cell. 2014;54:321–328. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dickson MA, et al. Human keratinocytes that express hTERT and also bypass ap16(INK4a)-enforced mechanism that limits life span become immortal yet retain normal growth and differentiation characteristics. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:1436–1447. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.4.1436-1447.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ammann TW, Belibasakis GN, Thurnheer T. Impact of early colonizers on in vitro subgingival biofilm formation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83090. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thurnheer T, Bostanci N, Belibasakis GN. Microbial dynamics during conversion from supragingival to subgingival biofilms in an in vitro model. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2016;31:125–135. doi: 10.1111/omi.12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Baglole CJ, et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor attenuates tobacco smoke-induced cyclooxygenase-2 and prostaglandin production in lung fibroblasts through regulation of the NF-kappaB family member RelB. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:28944–28957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800685200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen T, et al. The human oral microbiome database: a web accessible resource for investigating oral microbe taxonomic and genomic information. Database. 2010;2010:baq013. doi: 10.1093/database/baq013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:59–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huson DH, Auch AF, Qi J, Schuster SC. MEGAN analysis of metagenomic data. Genome Res. 2007;17:377–386. doi: 10.1101/gr.5969107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wood DE, Salzberg SL. Kraken: ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biol. 2014;15:R46. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-3-r46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Caporaso JG, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dabdoub SM, et al. PhyloToAST: Bioinformatics tools for species-level analysis and visualization of complex microbial datasets. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:29123. doi: 10.1038/srep29123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Matthews CR, et al. Host-bacterial interactions during induction and resolution of experimental gingivitis in current smokers. J. Periodontol. 2013;84:32–40. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.110662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Talukder MA, et al. Chronic cigarette smoking causes hypertension, increased oxidative stress, impaired NO bioavailability, endothelial dysfunction, and cardiac remodeling in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011;300:H388–396. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00868.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Lifev2: online annotation and display of phylogenetic trees made easy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W475–478. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gupta, N., Dabdoub, S. M. & Kumar, P. S. VORTEX: Visualizations for Omics Related Technology. J. Dent. Res.85A (2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All sequences are located in the servers of Argonne National Lab (MG-RAST) and relevant data are available from the authors.