Abstract

Purpose: The aim was to examine the predictors of improvement of quality of life after 2 years of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

Methods: In all, 208 patients who underwent the elective CABG at the Institute for Cardiovascular Diseases Dedinje in Belgrade were contacted and examined 2 years after the surgery. All patients completed Nottingham Health Profile Questionnaire part one.

Results: Two years after CABG, quality of life (QOL) in patients was significantly improved in all sections compared to preoperative period. Independent predictors of QOL improvement after 2 years of CABG were found to be serious angina under sections of physical mobility [p = 0.003, odds ratio (OR) = 1.76, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.21–2.55], energy (p = 0.01, OR = 1.63, 95% CI: 1.11–2.38), sleep (p = 0.005, OR = 1.65, 95% CI: 1.16–2.35), pain (p <0.001, OR = 2.43, 95% CI: 1.57–3.77), absence of hereditary load in energy section (p = 0.002, OR = 0.35, 95% CI: 0.18–0.68), male sex in the sleep section (p = 0.03, OR = 0.43, 95% CI: 0.20–0.93), and absence of diabetes in pain section (p = 0.006, OR = 0.27, 95% CI: 0.10–0.68).

Conclusion: Predictors of improvement of QOL after 2 years of CABG are serious angina, absence of hereditary load, male sex, and absence of diabetes.

Keywords: quality of life, coronary artery bypass surgery, predictors, improvement

Introduction

Today’s concept of patient care implies an attitude that we do not only care whether the patient is alive and how long he lives, but also how he lives and how satisfied he is with his life. This is why the World Health Organization in its manifesto, “The vision of Health for All,” published in 1993, puts forward slogans “Add Years to Life,” but also “Add life to years.”1) This concept provides an equal place to quality of life (QOL; alongside survival) in assessing the prognosis of disease after an intervention. QOL is a unique personal perception, the way people evaluate their own health condition and medical aspects of their lives.2) The proper assessment of the QOL is achieved through simplified choice of priorities in planning of therapeutic protocols, faster and better communication between doctors and patients, and simple detection of potential problems in patients. It is also the most accurate way to find out how realistic are expectations of patients regarding treatment, as well as the best option in monitoring changes during the treatment, quality of care provided to patients, and the overall treatment outcome.

In 2014, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) celebrated 50 years since the first intervention was done back in 1964.3) This intervention significantly improves the survival of patients with coronary disease, as well as their QOL.4) In patients with less advanced coronary disease, decision to carry out the surgery is based on alleviating the symptoms of angina and improving the QOL. Until now, it is mainly reported on the predictors of deterioration in QOL after CABG. Little is as yet known about the predictors of QOL improvement after the intervention, and our study precisely deals with this subject.

Materials and Methods

A total of 243 consecutive patients were studied. The patients underwent elective CABG at the Institute for Cardiovascular Diseases “Dedinje’’, Belgrade. In an average period of 2 years and 4 months ± 4 months after the surgery contact is established with 208 patients.During the monitoring period, 19 patients died, whereas 16 did not complete the questionnaire after 2 years. The study was approved by the relevant ethical committee. Nottingham Health Profile Questionnaire part one (NHP 1)5) is used as a model for the questionnaire. NHP 1 examined QOL in six areas: physical mobility (PM), social isolation (SI), emotional reaction (ER), energy (En), pain, and sleep. The patients were personally interviewed immediately before and 6 months and 2 years after CABG. Scores were ranked from 0 to 100, adding some weight issues specified by Thurstone’s method of paired comparisons, to any positive response. Response weight is determined by examining a large sample of the general population.6) A higher score indicates a greater disruption in the QOL.

The data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Preoperative and postoperative results for each section of the QOL, and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class before and after surgery were compared by using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs rank test. Preoperative and postoperative results for each QOL section were compared with reference values obtained by testing a sample of the general population, and which are adapted to the sex and age groups of the examinees included in the study. Preoperative and postoperative QOL for each patient were also compared. In this way, we determine which patients experienced improvement, which of them experienced deterioration, and in which the QOL after surgery did not change. To determine the predictors of QOL improvements after 2 years of CABG, we conducted univariate and multivariate logistic regression with binary-dependent variable (improved or not improved). During the examination of predictors of improvement, patients with no changes in postoperative QOL were considered together with the patients with worsening QOL. Variables with a significance level ≤0.20 in univariate are included in the multivariate analysis.

Results

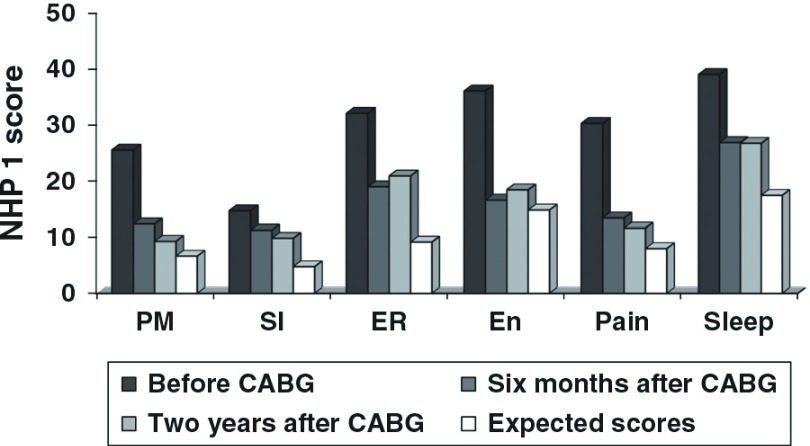

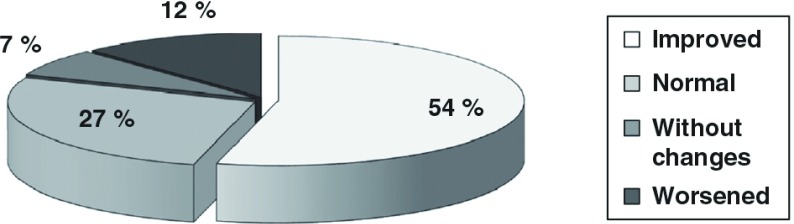

Among the examined patients, 195/243 (80%) of them were males. Average age of patients was 59 ± 8 years. Preoperative clinical characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Two years after CABG, QOL in patients was significantly improved in all sections compared to the preoperative period, and in sections PM, En, and pain, it approaches to the expected values for age and sex (Fig. 1). Compared with the 6-month period, 2 years after CABG, QOL was improved in the section PM. In other sections, there were no differences in the QOL after 6 months and 2 years of the intervention. Compared to the preoperative period, QOL after 2 years of CABG was improved in 54% of patients, worsened at 12%, no change in 7%, whereas it was normal in 27% of patients before and 2 years after CABG surgery (Fig. 2). After CABG, the patients’ symptomatology was significantly improved and NYHA functional class was significantly corrected (Table 2). The average NYHA class of patients before CABG surgery was 2.29 ± 0.62, 6 months after CABG surgery was 1.63 ± 0.60 (p <0.001), and 2 years after CABG was 1.61 ± 0.68 (p <0.001 compared to preoperative p = 0.08 compared with NYHA class 6 months after CABG).

Table 1. Preoperative clinical characteristics of the study population.

| Variable | Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 59.0 ± 8.0 | |

| Duration of CHD, years | 4.5 ± 5.9 | |

| CCS angina class | 1.9 ± 1.0 | |

| NYHA functional class | 2.3 ± 0.7 | |

| EuroSCORE | 3.4 ± 2.3 | |

| No. of patients | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 195 | 80 |

| Ejection fraction <50% | 144 | 59 |

| Risk factors | ||

| Hypertension | 171 | 70 |

| Smoking | 138 | 57 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 146 | 60 |

| Diabetes | 46 | 19 |

| Heredity | 135 | 56 |

| Obesity (BMI >30) | 66 | 27 |

| Stress | 146 | 60 |

| Physical inactivity | 124 | 51 |

| Left main disease | 14 | 6 |

| Three-vessel disease | 153 | 63 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 146 | 60 |

| Redo surgery | 13 | 5 |

| Comorbid diseasesa | 114 | 47 |

aDiabetes mellitus showed with the risk factors for ischemic heart disease. BMI: body mass index; CCS: canadian cardiology society; CHD: coronary heart disease; EuroSCORE: European system for cardiac operative risk evaluation; NYHA: New York heart association

Fig. 1. Mean values of NHP 1 score for each section QOL before, 6 months and 2 years after coronary artery bypass, compared with expected values. Compared to preoperative period, patients had significantly improved the QOL, both 6 months and 2 years after CABG (p <0.01 for all sections QOL). Compared to the condition 6 months after CABG surgery, 2 years after QOL was improved in the PM section (p = 0.002), and for other sections there were no significant changes. CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; QOL: quality of life; NHP: Nottingham health profile; PM: physical mobility; SI: social isolation; ER: emotional reaction; En: energy.

Fig. 2. Change in overall quality of life after 2 years of coronary artery bypass (total NHP 1 score). Normal = normal quality of life before and after coronary artery bypass (compared with reference values obtained by testing a sample of the general population). Without changes = disturbed quality of life, without changes after coronary artery bypass. NHP: Nottingham health profile.

Table 2. NYHA class in patients before, six months and two years after CABG.

| NYHA class | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | ||

| Before CABG | Number of patients | 16 | 98 | 66 | 3 |

| Percentage (%) | 9 | 53 | 36 | 2 | |

| Six months after CABG | Number of patients | 78 | 94 | 11 | 0 |

| Percentage (%) | 43 | 51 | 6 | 0 | |

| Two years after CABG | Number of patients | 89 | 79 | 13 | 2 |

| Percentage (%) | 49 | 43 | 7 | 1 | |

CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; NYHA: New York heart association

The strongest independent predictor of QOL improvement after 2 years of CABG has singled high Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) angina class in sections of PM [p = 0.003, odds ratio (OR) = 1.76, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.21–2.55], energy (p = 0.01, OR = 1.63, 95% CI: 1.11–2.38), sleep (p = 0.005, OR = 1.65, 95% CI: 1.16–2.35), and pain (p <0.001, OR = 2.43, 95% CI: 1.57–3.77). Under SI section, the difference was very close to statistical significance, but only in the section of ERs difference was not significant, not even in univariate analysis. Other predictors of improvement were the absence of hereditary load in the energy section (p = 0.002, OR = 0.35, 95% CI: 0.18–0.68), male sex in the section sleep (p = 0.03, OR = 0.43, 95% CI: 0.20–0.93), and absence of diabetes in section pain (p = 0.006, OR = 0.27, 95% CI: 0.10–0.68) (Table 3).

Table 3. Independent predictors of quality of life improvement after 2 years of coronary artery bypass surgery.

| Section | Variablea | (Univariate) | (Multivariate analysis) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p value | Coefficient | p value | OR | 95% CI | ||

| Physical mobility | Gender | 0.06 | 0.84 | 0.11 | 2.33 | 0.82–6.58 |

| Age | 0.1 | 0.02 | 0.40 | 0.97 | 0.26–1.07 | |

| Class of angina (CCS) | 0.001 | 0.56 | 0.003b | 1.76 | 1.21–2.55 | |

| Social isolation | Gender | 0.04 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 1.46 | 0.65–3.25 |

| Age | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.41 | 1.02 | 0.97–1.07 | |

| Marital status | 0.04 | −0.67 | 0.20 | 0.51 | 0.18–1.44 | |

| Hypertension | 0.02 | 0.56 | 0.13 | 1.76 | 0.84–3.67 | |

| Smoking | 0.07 | −0.19 | 0.43 | 0.82 | 0.51–1.33 | |

| Physical inactivity | 0.16 | 0.30 | 0.37 | 1.36 | 0.81–3.68 | |

| Class of angina (CCS) | 0.01 | 0.36 | 0.057 | 1.43 | 0.99–2.08 | |

| Emotional reaction | Hypertension | 0.07 | 0.60 | 0.07 | 1.82 | 0.94–3.55 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 0.17 | 0.47 | 0.14 | 1.60 | 0.86–2.99 | |

| Heredity | 0.17 | −0.47 | 0.14 | 0.63 | 0.33–1.17 | |

| Stress | 0.05 | 0.66 | 0.06 | 1.95 | 0.95–4.00 | |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 0.09 | 0.40 | 0.11 | 1.49 | 0.91–2.44 | |

| Energy | Gender | 0.15 | 0.59 | 0.15 | 1.25 | 0.81–4.05 |

| Age | 0.009 | 0.02 | 0.36 | 1.02 | 0.97–1.08 | |

| Hypertension | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.64 | 1.19 | 0.58–2.45 | |

| Smoking | 0.04 | −0.23 | 0.36 | 0.80 | 0.49–1.29 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.16 | −0.78 | 0.09 | 0.46 | 0.18–1.14 | |

| Heredity | 0.002 | −1.05 | 0.002b | 0.35 | 0.18–0.68 | |

| Class of angina (CCS) | 0.001 | 0.49 | 0.01b | 1.63 | 1.11–2.38 | |

| EuroSCORE | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.58 | 1.05 | 0.88–1.24 | |

| Sleep | Gender | 0.05 | −0.85 | 0.03b | 0.43 | 0.20–0.93 |

| Smoking | 0.12 | −0.40 | 0.06 | 0.67 | 0.44–1.02 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.08 | −0.31 | 0.52 | 0.73 | 0.29–1.87 | |

| Class of angina (CCS) | 0.01 | 0.50 | 0.005b | 1.65 | 1.16–2.35 | |

| Comorbidity | 0.04 | −0.52 | 0.16 | 0.59 | 0.28–1.23 | |

| Pain | Diabetes mellitus | 0.01 | −0.90 | 0.006b | 0.27 | 0.10–0.68 |

| Duration of CAD | 0.05 | −0.46 | 0.07 | 0.91 | 0.83–1.01 | |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 0.04 | 0.78 | 0.054 | 0.50 | 0.24–1.01 | |

| Class of angina (CCS) | <0.001 | 0.34 | <0.001b | 2.43 | 1.57–3.77 | |

| Ejection fraction | 0.16 | 0.40 | 0.88 | 1.00 | 0.96–1.05 | |

| EuroSCORE | 0.16 | 1.38 | 0.86 | 0.98 | 0.78–1.23 | |

aVariable selected from univariate analysis (p ≤0.20). bStatistically significant in multivariate analysis. CCS: canadian cardiovascular society classification of angina; CAD: coronary artery disease; EuroSCORE: European system for cardiac operative risk evaluation; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio

Discussion

QOL in patients with ischemic heart disease is often worsened, as in those with significant health problems, and those who do not feel seriously ill. The main symptom of coronary artery disease, chest pain, is the main reason for QOL worsening. Patients who had a heart attack, in addition to physical constraints, often have emotional problems as well as problems with social contacts and sleep. The QOL of coronary patients, who should undergo coronary artery bypass, is usually disrupted for two main reasons. The first is already mentioned coronary disease with problems and limitations that it entails; the second is the fact that patients will undergo to one of the serious surgical interventions, sometimes with an uncertain outcome, and in particular it can affect the emotional state and the sleep of the patient.

CABG procedure today is almost routine, widespread, and poses a significant health and social value. It can be done with the use of extracorporeal circulation or without (“on-pump” or “off-pump”), with small differences in the efficiency of these two methods.7,8) Our research included patients who were operated by “on-pump” method, which is today represented in the world in over 80% of procedures,9) and which still in certain categories of patients shows better results.10) We have already reported on QOL improvement that patients have 6 months after CABG.11) This prosperity is also maintained 2 years after CABG, with the fact that in the section of PM there is an additional improvement in QOL. In the first 6 months after surgery, patients are, in spite of significant repair of PM, compared to the preoperative period, spared of major physical effort. Two years after CABG, they become more confident in themselves and their health and that is why we find better results in PM compared with the 6-month period. QOL is improved in more than half of patients after 2 years of CABG. Considering that the QOL is normal before and after surgery in almost one-third of patients, a significant number of the 81% of patients with a good QOL after 2 years of surgery is achieved (Fig. 2). In only 12% of patients is found a QOL worsening. Two years after coronary artery bypass, symptomatology is significantly improved compared to the preoperative period, patients less complain of pain in the chest, shortness of breath, fatigue when walking and palpitations, and that is the reason the NYHA class of patients is significantly better. No significant difference in the NYHA class between the 6-month and 2-year period after surgery is found.

It is very important to determine whether and which preoperative clinical factors may affect the QOL after the treatment by therapeutic procedures, and thus define the patient population that has the greatest benefit, respectively, the best clinical improvement afterwards.12) The strongest predictor of QOL improvement after 2 years of CABG was the presence of severe angina before the surgery (in four of the six sections of QOL) (Table 3). There is a strong positive correlation between the severity of angina pectoris and QOL worsening.13,14) Since most of the patients after the surgery were relieved of angina difficulties, the greatest improvement is registered at those who preoperatively had a high degree of angina. This is consistent with findings of other authors who report that significantly worsened QOL is the predictor of its improvement after CABG.15) In patients who do not have angina before surgery, the QOL before CABG is generally good, so there are conditions for its deterioration after the intervention. We have already shown that serious angina is an independent predictor of QOL improvement after 6 months of CABG,13) and now for the first time we report that it remains the most powerful predictor of improvements even 2 years after the intervention.13)

The absence of hereditary load was an independent predictor of QOL improvement in the energy section. The presence of close relatives who had or have the coronary artery disease, like sudden cardiac death of a father, mother, brother, or some other very close relative, has a bad influence to the life energy in patients after 2 years of coronary artery bypass. People without hereditary load have a better chance of improving QOL in the energy section.

Before CABG, women have worse QOL in all sections, except the sleep section, where QOL is equally worsened both in men and women.16) The largest number of reports shows that men do better after coronary artery bypass in terms of forecasts and the expected QOL. Male gender is an independent predictor of QOL improvement in sleep section after 2 years of CABG. Differences between genders regarding the outcome of various diseases in terms of the efficiency of certain therapeutic procedures, including CABG, are usually explained by the influence of the biological (hormonal) or social factors. In our earlier work, we discussed in detail about the differences in QOL between men and women after CABG and the causes of these differences,16) so we will not repeat it here.

Coronary artery bypass improves the survival and QOL in diabetic patients with coronary artery disease. People with diabetes have poorer QOL than non-diabetics, both before and 5 years after coronary artery bypass.17) There is an evident advantage of coronary artery bypass, compared to percutaneous procedures, the prognosis of patients with triple-vessel disease, particularly in diabetics. They have particularly large benefits of surgery while incorporating arterial grafts.18) Diabetic patients who are candidates for a kidney transplantation may have a particularly strong indication for coronary artery bypass.19) However, coronary disease patients with diabetes have a poorer prognosis after severe cardiovascular events and interventions compared to non-diabetics. The higher mortality and poorer QOL in women after CABG are explained by a higher incidence of diabetes compared to men. Our results show that the absence of diabetes in patients was an independent predictor of QOL improvement after 2 years of CABG in section pain. Other studies, however, show that diabetes is a predictor of QOL worsening after CABG.11,20) Although the influence of diabetes to the appearance of neuropathy can be the cause of minor sensibility for each pain, even for angina although in this case is more important diabetes impact on the progression of coronary artery disease and the re-emergence of anginal pain. In addition, in diabetics with coronary disease, in comparison to non-diabetics, depression after serious cardiovascular events is more frequent.21)

Acknowledgment

The authors owe special gratitude to the patients and staff at the Institute for Cardiovascular Diseases “Dedinje,” Belgrade.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1).Zdravkovicć M, Krotin M, Deljanin-Ilicć M, et al. [Quality of life evaluation in cardiovascular diseases]. Med Pregl 2010; 63: 701-4. (in Serbian) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Editorial Quality of life and clinical trials. The Lancet 1995; Vol. 346, No. 8966: 1-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Head SJ, Kieser TM, Falk V, et al. Coronary artery bypass grafting: part 1—the evolution over the first 50 years. Eur Heart J 2013; 34: 2862-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Japanese Associate for coronary artery surgery (JACAS) Coronary artery surgery results 2013, in Japan. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014; 20: 332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Hunt SM, McKenna SP, McEwen J, et al. The Nottingham health profile: subjective health status and medical consultations. Soc Sci Med 1981; 15: 221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).McKenna SP, Hunt SM, McEwen J. Weighting the seriousness of perceived health problems using Thurstone’s method of paired comparisons. Int J Epidemiol 1981; 10: 93-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Luo T, Ni Y. Short-term and long-term postoperative safety of off-pump versus on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting for coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis for randomized controlled trials. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015; 63: 319-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Lamy A, Devereaux PJ, Prabhakaran D, et al. Effects of off-pump and on-pump coronary-artery bypass grafting at 1 year. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 1179-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Hillis LD, Smith PK, Anderson JL, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a report of the american college of cardiology foundation/american heart association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2011; 124: e652-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Singh A, Schaff HV, Mori Brooks M, et al. On-pump versus off-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery among patients with type 2 diabetes in the bypass angioplasty revascularization investigation 2 diabetes trial. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016; 49: 406-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Peric V, Borzanovic M, Stolic R, et al. Predictors of worsening of patients’ quality of life six months after coronary artery bypass surgery. J Card Surg 2008; 23: 648-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Hlatky MA, Boothroyd DB, Melsop KA, et al. Medical costs and quality of life 10 to 12 years after randomization to angioplasty or bypass surgery for multivessel coronary artery disease. Circulation 2004; 110: 1960-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Peric VM, Borzanovic MD, Stolic RV, et al. Severity of angina as a predictor of quality of life changes six months after coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2006; 81: 2115-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Sjöland H, Wiklund I, Caidahl K, et al. Relationship between quality of life and exercise test findings after coronary artery bypass surgery. Int J Cardiol 1995; 51: 221-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Herlitz J, Brandrup-Wognsen G, Caidahl K, et al. Improvement and factors associated with improvement in quality of life during 10 years after coronary artery bypass grafting. Coron Artery Dis 2003; 14: 509-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Peric V, Borzanovic M, Stolic R, et al. Quality of life in patients related to gender differences before and after coronary artery bypass surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2010; 10: 232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Herlitz J, Caidahl K, Wiklund I, et al. Impact of a history of diabetes on the improvement of symptoms and quality of life during 5 years after coronary artery bypass grafting. J Diabetes Complicat 2000; 14: 314-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Kurlansky P, Herbert M, Prince S, et al. Improved long-term survival for diabetic patients with surgical versus interventional revascularization. Ann Thorac Surg 2015; 99: 1298-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Rogers WJ, Coggin CJ, Gersh BJ, et al. Ten-year follow-up of quality of life in patients randomized to receive medical therapy or coronary artery bypass graft surgery. The coronary artery surgery study (CASS) Circulation 1990; 82: 1647-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Herlitz J, Wiklund I, Caidahl K, et al. Determinants of an impaired quality of life five years after coronary artery bypass surgery. Heart 1999; 81: 342-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Milani RV, Lavie CJ. Behavioral differences and effects of cardiac rehabilitation in diabetic patients following cardiac events. Am J Med 1996; 100: 517-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]