Highlights

-

•

Gallstones may be lost in a laparoscopic cholecystectomy and cause morbidity.

-

•

Diagnosis of complications are difficult.

-

•

Findings may be mistaken for malignancies unless clinical suspicion remains high.

-

•

Inflammation from lost stones can obstruct the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract.

-

•

Lost gallstones are best managed during the initial cholecystectomy.

Keywords: Lost gallstones, Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Gastric outlet obstruction, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Spilled gallstones from a laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be a source of significant morbidity, most commonly causing abscesses and fistulae. Preventative measures for loss, careful removal during the initial surgery, and good documentation of any concern for remaining intraperitoneal stones needs to be performed with the initial surgery.

Case report

An 80-year-old male with a history of complicated biliary disease resulting in a cholecystectomy presented to general surgery clinic with increasing symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction. CT imaging was concerning for a malignant process despite negative biopsies. A distal gastrectomy and Billroth II reconstruction was performed and final pathology showed dense inflammation with a single calcified stone incarcerated within the gastric wall of the inflamed pylorus and no malignancy.

Discussion

Stones lost during laparoscopic cholecystectomy are not innocuous and preventative measures for loss, careful removal during the initial surgery, and good documentation of any concern for remaining intraperitoneal stones.

Conclusion

This is the first case of gastric outlet obstruction caused by an intramural obstruction of the pylorus from a spilled gallstone during a laparoscopic cholecystectomy and subsequent inflammation. This is an etiology that must be considered in new cases of gastric outlet obstruction and can mimic malignancy.

1. Introduction

For the past three decades, laparoscopic cholecystectomy has been the gold standard for treating gallstone disease, with shorter hospitalization, less postoperative pain, and better cosmetic results than open cholecystectomies [1]. Despite advantages to a minimally invasive cholecystectomy, there is an increase in the rate of ductal injuries and complications related to lost stones [2].

Spilled gallstones from a laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be a source of significant morbidity, with up to 12% leading to complications [2]. A recent systematic review of 111 publications cited intra-abdominal abscess as the most frequent (1.7/1000 laparoscopic cholecystectomies), followed by fistula formation [2]. However, there is a plethora of rarer sequelae including stone expectoration, stones within hernia sacs, stones within an ovary, and tubalithiasis [2]. Proximal intestinal obstruction (Bouveret syndrome) is an exceedingly rare complication of stones occurring in 1 in 10,000 cases of cholelithiasis [3].

There is significant diagnostic dilemma associated with these complications. First, there is often a substantial time delay between cholecystectomy and symptoms prompting patients to seek medical attention, with the median time interval of approximately 5 months [4]. Secondly, the presenting symptoms are wide ranging due to the multiple types of complications and location of spilled stones [5]. A complicating factor is the lack of surgeon documentation of stones spilled and their (possible) recovery at laparoscopic cholecystectomy [6]. Lastly, radiographic abnormalities caused by radiolucent stones are difficult to attribute to stone disease. If these stones are surrounded by a granulomatous reaction, the presence of underlying calculus is often missed or misinterpreted as an intra-abdominal neoplasia with peritoneal deposits from metastasis, endometriosis, focal liver masses, and lymph nodes [7].

We present an unusual case of gastric outlet obstruction secondary to an obstructing stone, masquerading as a possible malignancy, requiring distal gastrectomy and reconstruction. To our knowledge, this is the first case of gastric outlet obstruction caused by an intramural obstruction of the pylorus from a spilled gallstone during a laparoscopic cholecystectomy and subsequent inflammation.

This case report has been written in accordance with SCARE criteria [8].

2. Presentation of case

An 80-year-old male presented to the General Surgery clinic for symptoms consistent with gastric outlet obstruction. He had been seen in the clinic five years previously due to biliary disease requiring a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The patient was currently reporting a 4-month history of 30-pound weight loss, progressively worsening nausea, vomiting and significant gastroesophageal reflux. He had already been seen by a gastroenterologist who arranged for esophagogastroduoenoscopy (EGD) and computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen. EGD found retained gastric contents, with thickening of the pylorus and first part of the duodenum; biopsies taken were negative for malignancy. The CT demonstrated bulky, circumferential and irregular thickening and enhancement of the gastric wall at the level of the pylorus, involving the duodenal bulb (Fig. 1). The differential at the time included peptic ulcer disease, primary gastric neoplasm, infectious disease, or lymphoma.

Fig. 1.

Axial view of CT abdomen/pelvis with IV contrast demonstrating a bulky circumferential irregular thickening and enhancement of the gastric wall at the level of the pylorus involving the duodenal bulb. Additionally, there is a chronic ellipsoid pocket of fluid associated with the peritoneal lining posterior to the liver that was noted to represent an old abscess or hematoma cavity.

The decision was made to proceed with surgical management given his symptoms and the highly suspicious nature of his endoscopic and radiographic findings, despite negative pathology for malignancy. Intraoperatively, a firm palpable mass was felt in the distal pylorus; the area was quite adherent to the liver and the duodenum itself was quite adherent to the surrounding structures requiring careful dissection from the IVC, pancreas and porta hepatis. The duodenum was eventually dissected free and removed with the distal stomach. Reconstruction was performed with a retrocolic Billroth II anastomosis and insertion of a jejunal feeding tube. The pathology showed submucosal thickening in the region of the pylorus. A single calcified stone measuring 0.6 cm in diameter was identified incarcerated within the wall of the pylorus (Fig. 2A–B). Histologic sections from the gastric wall with the incarcerated stone (Fig. 2C–D) showed dense inflammation centered in the submucosa emanating from the cavity formed by the incarcerated stone. There was no dysplasia or malignancy identified.

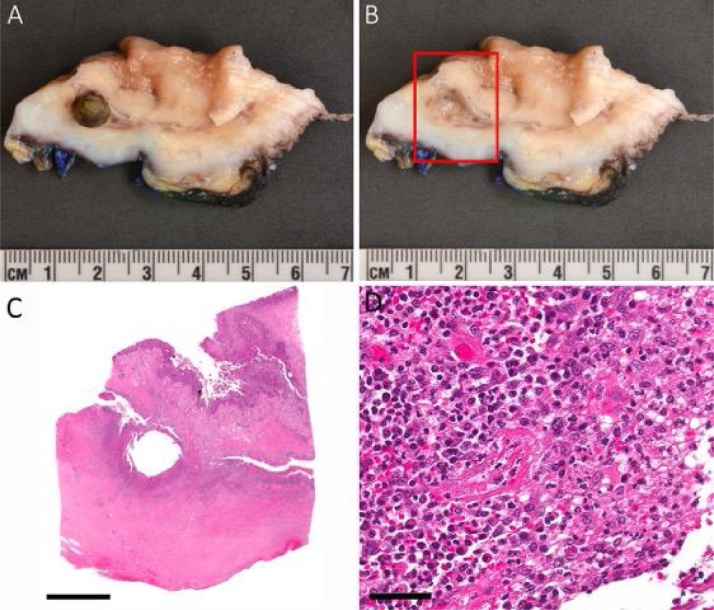

Fig. 2.

(A) cross section of the stomach with the incarcerated gallstone lodged within the wall. (B) image with the gallstone removed showing the cavity in the wall (red box denotes the area that was sampled in the histologic sections). (C) Low power photomicrograph (scale bar = 5 mm) showing the cavity in the wall with the overlying gastric mucosa. (D) High power photomicrograph (scale bar = 50 μm) showing mixed acute and chronic inflammation within the wall of the stomach.

The patient was slow to recover post operatively due to pre-operative wasting and pre- existing difficulty with mobilization but was eating well and able to be transferred to rehabilitation approximately one month after surgery.

3. Discussion

A gallstone spilled during cholecystectomy becomes a nidus for inflammation and incites a granulomatous response [7]. In particular, pigment stones precipitate a mesenchymal reaction akin to a granuloma, whereas contaminated pigment or cholesterol stones lead to abscess formation9. These (often) asymptomatic granulomas can masquerade as neoplastic deposits when patients are imaged for other reasons. Occasionally, as in this case, the low grade inflammatory response will continue and the gallstone can form any number of symptomatic sequelae including abscess, sinus tract, fistula, or erosion outside of the peritoneal cavity [7].

There have been a number of animal-based studies to investigate the consequences of spilled gallstones within the abdominal cavity. Johnson et al. studied rats with implanted gallstones and found that bile in combination with gallstones in the peritoneal cavity is associated with an increased risk of intra-abdominal adhesion formation and abscess formation [10]. Tzardis et al. performed a similar experiment in rabbits and found that the prevalence of septic complications was higher with retained intra-abdominal gallstones [11]. Gurleyik et al. also was able to show that chemical composition, particularly pigmented stones, has a significant influence on the sequelae of intra-abdominal gallstones, and infection may aggravate local reactions and complications [12]. In these studies, the unanimous recommendation was that stones should be retrieved to prevent infectious complications and inflammatory reactions or, patients with retained intraperitoneal pigment stones must be followed closely due to the high prevalence of complications [10], [11], [12].

During an open cholecystectomy, it is easy to recognize spillage of gallstones and their retrieval is much easier. More commonly, this complication is seen after a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, when retrieval of all spilled stones can be more challenging. Incidence of gallbladder perforation is 13–40%, with a mean of 18.3% and stones fall out of the gallbladder in 40% of those cases [13], [14]. Immediately closing the perforation with hemoclips, endoloops or suturing is possible with a smaller holes [15]. Many studies recommend collecting spilled bile and stones by irrigating the peritoneal cavity and locating the stones with oblique views of the scope or additional working cannulas [9]. Using a specimen bag, surgical glove, or condom to remove stones immediately after spillage is also a simple, safe, and inexpensive method for removal [16]. Additionally, large stones may be fragmented and removed via a 30-French sheath [16]. Contrastingly, some report that peritoneal irrigation and drain placement in Morrison’s pouch does not prevent postoperative complications [4].

The importance of documentation for both medico-legal purposes, as well as aiding in the diagnosis of late complications is emphasized in multiple studies. Both incorporating gallstone spillage and the potential complications while consenting the patient, as well as clear documentation of the intraoperative gallstone spillage in the medical report is recommended. This may increase the likelihood that it is considered in the differential diagnosis and allow for earlier diagnosis while reducing the medical risk these complications pose to patients [13].

4. Conclusion

Spilled gallstones have a low risk of future complications, however the potential for significant morbidity exists. Identifying the problem is difficult as the range of locations for stone deposits as well as the variety of consequences such as abscess or fistula are broad, thus eluding diagnosis. Diagnostic imaging is often difficult to interpret without a strong suspicion for stone involvement. Our case describes an 80-year old man with gastric outlet obstruction secondary to an intramural gallstone. This complication has not been reported in the literature and needs to be considered in the differential diagnosis of gastric outlet obstruction after laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

Not required by our institution for case reports.

Author contribution

Jennifer Koichopolos – Primary author. Wrote the manuscript and performed the literature review used for the introduction and discussion.

Moska Hamidi – Senior resident that was able to review the paper, provide assistance in writing and help with making the manuscript presentable for publication.

Matthew Cecchini – Pathology resident that provided the pathological information and written sections surrounding the pathology

Kenneth Leslie – Staff general surgeon, discovered the case and provided guidance and review for the case report to be written.

Consent

The patient has given consent for presentation and publication of his case without the inclusion of any identifying information.

Guarantor

Dr. Kenneth Leslie.

References

- 1.McSherry C.K. Cholecystectomy: the gold standard. Am. J. Surg. 1989;158:174–178. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(89)90246-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zehetner J., Shamiyeh A., Wayand W. Lost gallstones in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: all possible complications. Am. J. Surg. 2007;193:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wakefield E.G., Vickers P.M., Walters W. Cholecystoenteric fistulas. Surgery. 1939;5:674–677. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horton M., Florence M.G. Unusual abscess patterns following dropped gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am. J. Surg. 1998;175:375–379. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(98)00048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sathesh-Kumar T., Saklani A.P., Vinayagam R., Blackett R.L. Spilled gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a review of the literature. Postgrad. Med. J. 2004;80:77–79. doi: 10.1136/pmj.2003.006023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Habib E., Khoury R., Elhadad A. [Digestive complications of biliary gallstone lost during laparoscopic cholecystectomy] Gastroenterol. Clin. Biol. 2002;26:930–934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramamurthy N.K., Rudralingam V., Martin D.F. Out of sight but kept in mind: complications and imitations of dropped gallstones. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2013;200:1244–1253. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S. Orgill DP, for the SCARE group. the SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nooghabi A.J., Hassanpour M., Jangjoo A. Consequences of lost gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutan. Tech. 2016 June;26(3):183–192. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston S., O’Malley K., McEntee G. The need to retrieve the dropped stone during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am. J. Surg. 1994;167:608–610. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(94)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tzardis P.J., Vougiouklakis D., Lymperi M. Septic and other complications resulting from biliary stones placed in the abdominal cavity: experimental study in rabbits. Surg. Endosc. 1996;10:533–536. doi: 10.1007/BF00188402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gurleyik E., Gurleyik G., Yucel O. Does chemical composition have an influence on the fate of intraperitoneal gallstone in rat. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. 1998;8:113–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woodfield J.C., Rodgers M., Windsor J.A. Peritoneal gallstones following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: incidence, complications, and management. Surg. Endosc. 2004;18:1200–1207. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8260-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schafer M., Suter C., Klaiber C.H. Spilled gallstones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a relevant problem? A retrospective analysis of 10,174 laparoscopic cholecystectectomies. Surg. Endosc. 1998;9:344–347. doi: 10.1007/s004649900659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leslie K.A., Rankin R.N., Duff J.H. Lost gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: are they really benign? Can. J. Surg. 1994;37(June (3)):240–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trerotola S.O., Lillemoe K.D., Malloy P.C. Percutaneous removal of dropped gallstones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Radiology. 1993;188:419–421. doi: 10.1148/radiology.188.2.8327688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]