Abstract

Aims: Proliferative signaling involves reversible posttranslational oxidation of proteins. However, relatively few molecular targets of these modifications have been identified. We investigate the role of protein oxidation in regulation of SAMHD1 catalysis.

Results: Here we report that SAMHD1 is a major target for redox regulation of nucleotide metabolism and cell cycle control. SAMHD1 is a triphosphate hydrolase, whose function involves regulation of deoxynucleotide triphosphate pools. We demonstrate that the redox state of SAMHD1 regulates its catalytic activity. We have identified three cysteine residues that constitute an intrachain disulfide bond “redox switch” that reversibly inhibits protein tetramerization and catalysis. We show that proliferative signals lead to SAMHD1 oxidation in cells and oxidized SAMHD1 is localized outside of the nucleus.

Innovation and Conclusions: SAMHD1 catalytic activity is reversibly regulated by protein oxidation. These data identify a previously unknown mechanism for regulation of nucleotide metabolism by SAMHD1. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 27, 1317–1331.

Keywords: : SAMHD1, protein oxidation, HIV restriction, Aicardi–Goutieres syndrome, redox switch, enzyme catalysis

Introduction

Regulation of cellular deoxynucleotide triphosphate (dNTP) levels is essential for proper DNA synthesis and cell cycle progression. SAMHD1 hydrolyzes dNTPs (17, 40), to control dNTP pool concentrations (13, 30). Dysregulation of nucleotide metabolism can have dangerous biological consequences, and mutations in the SAMHD1 gene result in the development of familial chilblain lupus and Aicardi–Goutieres syndrome, a severe neurological autoimmune disease that resembles a congenital viral infection (10, 42, 45). SAMHD1 mutations have also been identified as a contributing factor to several types of cancers (7, 44, 51). SAMHD1 has garnered significant attention for its antiviral properties in nondividing hematopoietic cells, where it acts as an interferon-inducible host restriction factor against viral infections, including HIV (3, 4, 18, 20, 21, 31, 33, 48, 54). SAMHD1 is proposed to inhibit productive viral infection by maintaining dNTP levels below the effective concentration for viral DNA polymerases, thereby restricting viral DNA synthesis (25, 32, 53). However, SAMHD1 does not restrict HIV in actively dividing cells (9, 52, 55), implying a strong connection between its catalytic activity and cell cycle progression, but the mechanisms of SAMHD1 catalytic regulation have remained an open question.

Innovation.

Here we present a previously unknown mechanism for regulation of SAMHD1 catalytic activity through protein oxidation. This new information directly ties redox biology to regulation of deoxynucleotide pools, and presents another connection between oxidative signaling and cell proliferation.

Structural and biochemical studies of SAMHD1 have elucidated the precise mechanism of catalysis. Binding of deoxynucleotides in a regulatory site induces conformational rearrangements of the enzyme that result in tetramerization and catalytic activation (1, 19, 29, 58, 60). This finely tuned autoregulation, in which substrate also acts as an activating ligand, enables SAMHD1 to sense fluctuating dNTP concentrations and to respond according to the specific metabolic requirements of the cell. Efficient and accurate DNA synthesis and repair require strict control of dNTP concentrations, which peak during S-phase when large quantities of dNTPs are required for DNA replication (43). As a central effector of nucleotide concentration, SAMHD1 is likely responsive to regulatory pathways that govern cell cycle progression (36). Elucidating the mechanisms that regulate SAMHD1 activity is critical for defining its function at the interface of nucleotide metabolism, viral replication, and autoimmunity.

Protein oxidation is emerging as a crucial signaling mechanism in cellular metabolism, cell signaling, and cell cycle progression (12, 15, 16). Here we identify three critical cysteine residues of SAMHD1 (Cys341, Cys350, and Cys522) that create a “redox switch” through the formation of intrachain disulfide bonds to reversibly inhibit SAMHD1 tetramerization and dNTPase activity. We also demonstrate that SAMHD1 is oxidized in cells in response to proliferative signals and colocalizes with sites of protein oxidation outside of the nucleus. Finally, our data support a model in which Cys522 acts as the primary sensor of redox signals and forms a disulfide linkage with either Cys341 or Cys350 that destabilizes the binding of activating nucleotides, thereby inhibiting tetramerization and dNTP hydrolase activity.

Results

The dNTPase activity of SAMHD1 is reversibly inhibited by oxidation

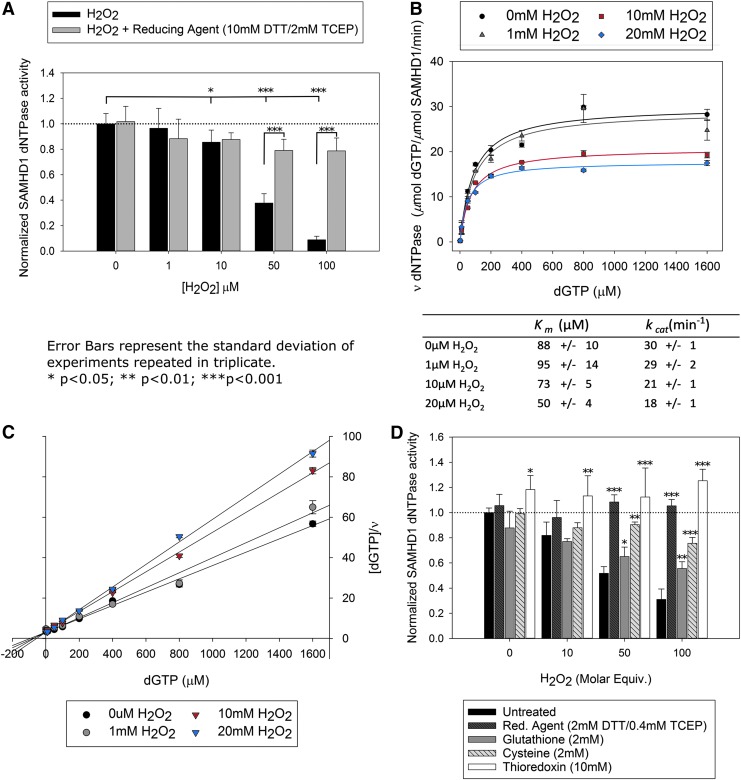

We investigated the impact of oxidation and reduction on SAMHD1 dNTP triphosphohydrolase activity. Oxidation of SAMHD1 by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) results in a significant decrease in SAMHD1 activity by 10 μM H2O2 and greater than 90% decrease in activity by 100 μM (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/ars). The addition of an excess of reducing agents (10 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]/2 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine [TCEP]) to the samples restores activity with no significant difference between the untreated sample and any of the concentrations of H2O2 tested.

FIG. 1.

SAMHD1 is reversibly inhibited by H2O2 oxidation. (A) SAMHD1 deoxynucleotide hydrolase activity is decreased in the presence of increasing H2O2, but is rescued after reduction of the protein with DTT/TCEP. (B, C) Kinetics of inhibition by H2O2 and Hanes–Woolf plot show a decrease in Vmax with relatively constant Km most consistent with a noncompetitive mechanism of inhibition. (D) Cellular reducing agents glutathione, cysteine, and thioredoxin–thioredoxin reductase are able to reactivate SAMHD1 after oxidation. Error values for activity measurements (A, D) represent the standard deviation (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001) and kinetic plots (B, C) are standard error of the mean. DTT, dithiothreitol; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; TCEP, tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine.

A more detailed investigation of the effect of oxidation on the kinetics of SAMHD1 dNTPase activity reveals a similar effect. SAMHD1 was incubated with increasing concentrations of H2O2, followed by addition of 100 μM deoxyadenosine triphosphate alpha S (dATPαS) and guanosine triphosphate (GTP). The nucleotides dATPαS and GTP induce the activated tetramer, but are not substrates for SAMHD1 and are not consumed in the reaction. Instead, they serve to maintain a steady state of enzymatic activation in the samples. Using this approach, SAMHD1 exhibits standard Michaelis–Menten kinetics, with a progressive decrease in turnover number in response to increasing H2O2 concentrations (Fig. 1B). An increase in H2O2 concentration results in a decrease of Vmax, while the Km is relatively unaffected. These data indicate that the reaction is inhibited by H2O2 in a manner consistent with noncompetitive inhibition (Fig. 1C). Taken together, these results reveal that H2O2 inhibits the catalytic capability of SAMHD1 through a mechanism that is both reversible and noncompetitive, which is consistent with oxidation of the enzyme.

We next tested the ability of common cellular reductants to rescue SAMHD1 activity following oxidation. Glutathione and cysteine restored the dNTPase activity of oxidized SAMHD1 (Fig. 1D). In addition, thioredoxin/thioredoxin reductase rescued SAMHD1 dNTPase activity (Fig. 1D), demonstrating that cellular reduction systems are capable of reducing oxidized SAMHD1.

Oxidation of SAMHD1 inhibits dNTPase activity by preventing subunit oligomerization

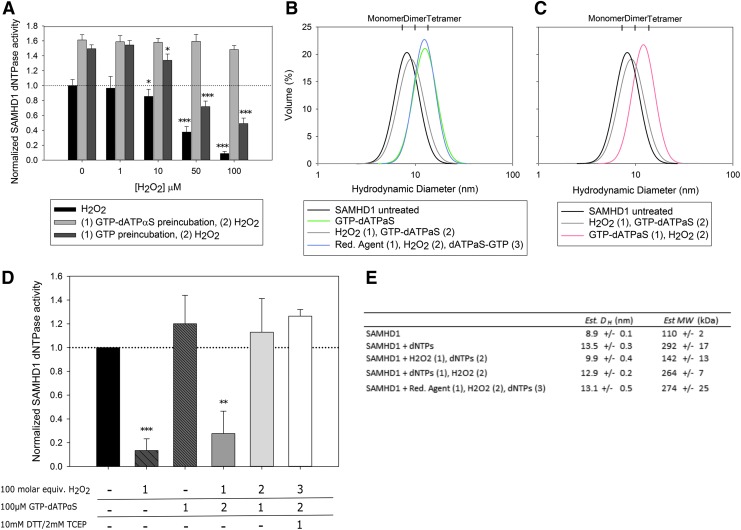

The triphosphate hydrolase activity of SAMHD1 is dependent on the ability of the protein to form a tetramer (23, 58, 59). To interrogate the mechanism of oxidative inactivation of SAMHD1 activity, we looked at the effects of oxidation on protein oligomerization. SAMHD1 was preincubated with either GTP alone or GTP and dATPαS. dNTPase activity was then measured following SAMHD1 oxidation. GTP and dATPαS together will induce tetramer formation but will not be consumed in the reaction, while GTP alone will bind the guanine-specific regulatory site but not induce tetramerization (22, 60). Both GTP and GTP-dATPαS samples display significantly increased dNTPase activity when compared to samples not preincubated with activating nucleotides (Fig. 2A). However, while GTP-only samples appear primed for dNTPase activity resulting in an increase in activity compared to the control, they exhibit a similar oxidative inactivation as untreated samples. Contrary to untreated and GTP-only samples, samples preincubated with GTP-dATPαS show no loss of activity even at the highest level of protein oxidation tested. This implies that nucleotide binding protects SAMHD1 from the effects of oxidation, either by shielding critical residues or through the formation of tetrameric species.

FIG. 2.

Oxidation of SAMHD1 prevents protein oligomerization. (A) Incubation of SAMHD1 with GTP-dATPαS to form the tetramer protects the enzyme activity from inactivation by oxidation (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared to respective 0 μM H2O2). (B) Dynamic light scattering measurements reveal SAMHD1 remains a monomer/dimer when oxidized, but can form tetramer after being reduced. (C) Preincubation with activating nucleotides before addition of H2O2 stimulates the formation of SAMHD1 tetramer. (D) dNTPase activity of SAMHD1 proteins used under conditions of the light scattering experiments shows that oxidized protein is unable to form a tetramer and has reduced activity. (E) Estimated hydrodynamic radii and molecular weights from dynamic light scattering experiments in B and C. dATPαS, deoxyadenosine triphosphate alpha S; dNTP, deoxynucleotide triphosphate; GTP, guanosine triphosphate.

Next, we used dynamic light scattering (DLS) to evaluate the formation of SAMHD1 tetramers as a function of protein oxidation. Dynamic light scattering provides a measure of hydrodynamic diameter (DH) and is able to differentiate the oligomeric states of SAMHD1. The average DH of untreated SAMHD1 measures 8.9 nm (Fig. 2B, E), which translates to a weight-averaged molecular weight of 110 kDa, and represents the dynamic monomer–dimer equilibrium of SAMHD1 observed in solution without activating nucleotides present (SAMHD1 monomer = 72.2 kDa). As expected, the addition of activating nucleotides results in the formation of the tetrameric species (DH = 13.5 nm, Mw = 292 kDa). Oxidation of SAMHD1 inhibits formation of the tetrameric species in the presence of activating nucleotides (DH = 9.9 nm, Mw = 142 kDa) and instead appears to sequester the enzyme in the dimeric state. The addition of reducing agent before protein oxidation mitigates its inhibitory effect and allows for enzyme tetramerization (DH = 13.1 nm, Mw = 274 kDa). Preincubation with activating nucleotides before protein oxidation also facilitates enzyme tetramerization supporting the hypothesis that tetramerization shields SAMHD1 from the inhibitory effects of oxidation (Fig. 2C). The phosphohydrolase activities of samples used in the light scattering experiments were tested and show results similar to those in Figure 2A, correlating with the ability of SAMHD1 to form tetramers (Fig. 2D). Alternative experimental approaches investigating the oligomeric state of SAMHD1 under conditions similar to those used in the DLS experiments returned consistent results. Both glutaraldehyde crosslinking resolved by Western blotting and analytical size exclusion chromatography linked to multiangle light scattering detectors (SEC-MALS) reveal a reduction of SAMHD1 tetramerization in the presence of H2O2 (Supplementary Fig. S2).

SAMHD1 contains multiple redox-sensitive cysteines that form disulfide bonds when oxidized

Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated enzymatic inactivation often occurs through the oxidation of specific cysteinyl thiolates to sulfenic acid (R-SOH), which can further form various reversible or irreversible chemical modifications to the enzyme (39). The reversible nature of SAMHD1s catalytic inhibition by micromolar levels of H2O2 indicated the potential for a similar cysteine-mediated mechanism for enzymatic inactivation. SAMHD1 contains thirteen cysteine residues, and a review of SAMHD1 structures available in the Protein Data Base reveals that three cysteines (Cys341, Cys350, and Cys522) are in proximity to each other and adjacent to the regulatory nucleotide binding pockets (Fig. 3A). Residue Cys522 is in a flexible and often unstructured loop, while Cys341 and Cys350 form a disulfide bond in at least four structures (5AO4, 4RXO, 4MZ7, 3 U1 N) (2, 17, 59, 60), which is absent in the remainder of published structures. In addition, in a primary sequence alignment of SAMHD1 from various vertebrates, these cysteine residues are all highly conserved (Supplementary Fig. S3).

FIG. 3.

Identification of SAMHD1 redox-sensitive cysteines. (A) Structure of SAMHD1 monomer showing position of C341, C350, and C522 adjacent to the regulatory nucleotide binding site. (pdbid: 4MZ7) (59). (B) Mass spectrometry results summarizing chemical modifications to indicated SAMHD1 cysteine residues under varying redox conditions (IAA; iodoacetamide). (C) Mass matrix heat map representations of probable disulfide pairs from MS/MS data.

Analysis of residue-specific redox sensitivity was carried out using mass spectrometry (14). Protein S-sulfenylation, the conversion of a cysteinyl thiolate to sulfenic acid, is a common first step in the oxidative signaling mechanism that leads to the formation of a disulfide bond or a sulfinic (R-SO2H) or sulfonic (R-SO3H) acid chemical moiety (37, 56). The reagent 5,5-dimethyl-1,3-cyclohexanedione (dimedone) covalently reacts with cysteine sulfenic acids, and provides a means of identifying cysteine residues sensitive to redox signals. When SAMHD1 is oxidized in the presence of dimedone, multiple labeled cysteine residues are identified indicating the formation of sulfenic acid (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. S4). In addition, SO2 and SO3 chemical moieties are observed on these three residues under all conditions, indicating their sensitivity to redox chemistry.

Tandem mass spectrometry search algorithms were also used to identify the disulfide bonds present in SAMHD1 samples oxidized in the absence of dimedone. Computational algorithms [Mass Matrix (57) and p-linkSS (35)] were used to search the experimental mass spectra of SAMHD1 following oxidizing treatments. Both identified Cys341-Cys350 as the predominant intrachain disulfide bond formed by SAMHD1 (Fig. 3C and Supplementary Fig. S5). Several other disulfide linkages were identified with lower scores. Many of these also involved at least one cysteine from the Cys341, Cys350, and Cys522 triad, providing further evidence for the redox sensitivity of these particular residues and hinting at a possible dynamic thiol–disulfide exchange mechanism.

Cys341, Cys350, and Cys522 are the primary regulators of redox sensitivity and are important for catalytic function

We examined the role of identified cysteine residues in modulating the redox sensitivity of SAMHD1. Cysteine to alanine mutants of SAMHD1 were tested in vitro for redox sensitivity. We also tested an N-terminal deletion of SAMHD1 that contains only the catalytic HD domain (residues 120–626) (HD1Δ). The C522A mutant SAMHD1 shows no significant inhibition by oxidation (Fig. 4A). Consistent with this, dynamic light scattering experiments using the C522A mutant SAMHD1 protein show that oxidation does not inhibit tetramerization, unlike the wild-type protein (Fig. 4B), implying that C522 plays a critical role in sensing redox signals and translating them into a structural message that inhibits tetramerization and subsequent SAMHD1 catalysis. The other mutants tested are inactivated by oxidation, suggesting that alone they are not responsible for the mechanism of inactivation of SAMHD1 (Fig. 4A). While the inhibitory effect of oxidation on the HD1Δ enzyme is not as dramatic as in wild type, presumably due to the enhanced catalytic capacity of HD1Δ, the inhibition of the HD1Δ enzyme is significant as it localizes the primary mechanism for oxidative inactivation to the cysteine residues in the catalytic HD domain.

FIG. 4.

Cys341, Cys350, and Cys522 are the primary regulators of redox sensitivity. (A) Mutational analysis of SAMHD1 shows C522A mutant protein is resistant to H2O2 oxidation (*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001). (B) Dynamic light scattering reveals that C522A SAMHD1 protein can form a tetramer after H2O2 treatment. (C) SAMHD1 proteins separated by nonreducing SDS-PAGE show the formation of a disulfide species after H2O2 exposure. The disulfide bond is removed by reducing agents (DTT/TCEP) or blocked by preincubation with activating nucleotides. The C522A SAMHD1 and C341A,C350A SAMHD1 show no disulfide species. Uncropped images of gels shown in Supplementary Figure S10. SDS-PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulfate/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

One commonly observed manifestation of redox signals translated into structural motifs that alter enzyme activity is the formation of an intrachain disulfide bond, which can be observed by differential migration patterns using nonreducing denaturing gel electrophoresis (8, 37). SAMHD1 wild-type and Cys mutants were exposed to increasing concentrations of H2O2 or some combination of H2O2, reducing agent, and activating nucleotides. The reaction products separated on nonreducing sodium dodecyl sulfate/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) clearly show the emergence of a disulfide-containing band in response to increasing H2O2 in the wild-type protein (Fig. 4C). In the presence of reducing agent or preincubation with activating nucleotides, the oxidized SAMHD1 band is not observed, implying that either of these agents can prevent formation of the disulfide-containing species. C341A and C350A SAMHD1 proteins also form a disulfide bond on oxidation, with the C350A mutant appearing to be more susceptible to disulfide formation than the wild type. These results are interesting because they reveal that the disulfide linkage is not strictly between Cys341 and Cys350 as is observed in crystal structures. The C522A and C341-350A mutants provide insight into a potential molecular mechanism. In neither of these mutant proteins is a disulfide species observed, indicating that the disulfide linkage does indeed consist of some arrangement of the three Cys residues (341, 350, and 522), and that Cys522 can form a disulfide linkage with either Cys341 or Cys350. In the 500 μM H2O2 sample, the C341-C350A monomer is less pronounced, with much of the protein forming a high-molecular-weight aggregate that does not migrate into the gel. This is consistent with our experience that the C341-350A mutant rapidly aggregates in the absence of reducing agent (size exclusion chromatography data not shown). Circular dichroism (CD) analysis suggests that this may, in part, be related to altered structural stability stemming from a reduction in alpha-helix content (Supplementary Fig. S6). This underscores the importance of Cys341 and Cys350 for protein stability while hinting at a protective function against nonspecific Cys522 oxidation. As a control, the C320A mutant, which is structurally distant from the Cys522, Cys341, and C350 triad, shows the formation of disulfide bonds similar to wild type.

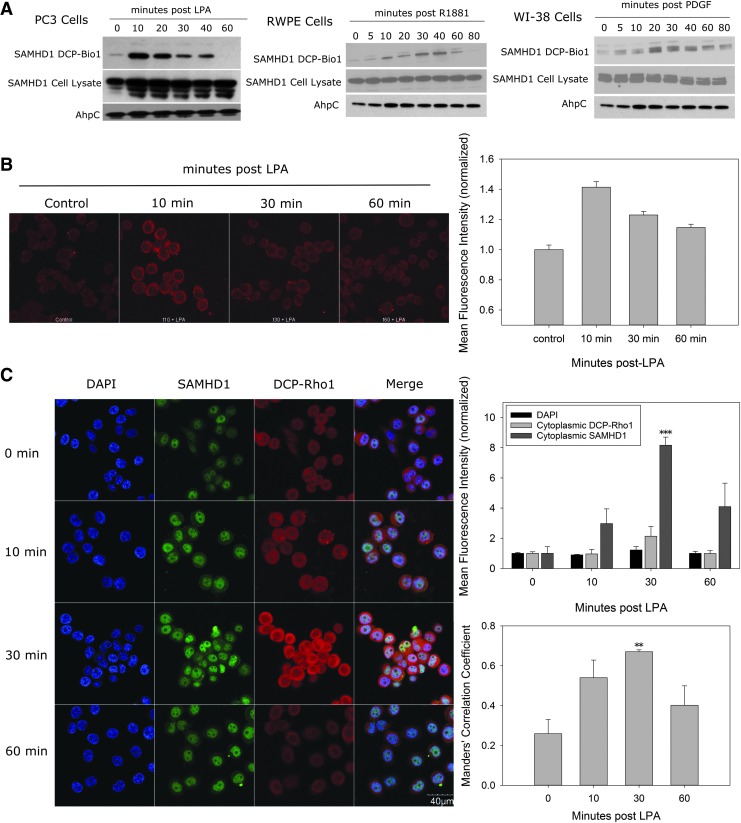

SAMHD1 is oxidized in vivo in response to proliferative signals

Next, we looked for evidence of SAMHD1 oxidation in cells. We used an established system of treating PC3 prostate cancer cells, RWPE-1 prostate epithelial cells, and WI-38 lung fibroblast cells with lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), R1881, and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), respectively, to elicit intracellular production of ROS (28, 34, 49). Oxidized proteins were labeled with a dimedone-like probe conjugated to biotin (DCP-Bio1) and affinity captured using streptavidin beads (Supplementary Fig. S7) (27). Labeled proteins and the respective total lysate were immunoblotted and probed with an anti-SAMHD1 antibody. Following addition of the proliferative agent, an oxidized species of SAMHD1 is observed, demonstrating that SAMHD1 is indeed oxidized in intact cells (Fig. 5A and Supplementary Fig. S8). Interestingly, the oxidation of SAMHD1 follows a specific time course in each cell type. The signal initially increases following stimulation before the oxidation intermediate disappears around 60–90 min poststimulation. The total amount of SAMHD1 in whole cell lysate does not change. Further investigation of SAMHD1 activity in vivo provides additional evidence for the importance of oxidation as a means for catalytic regulation. We directly measured SAMHD1 catalytic activity from fibroblast cells transfected with SAMHD1 wt, SAMHD1 C522A, or empty vector and ± PDGF treatment, a known activator of ROS production. SAMHD1 activity in cells expressing wt protein is diminished after treatment with PDGF when compared to no PDGF (Supplementary Fig. S9). However, the C522A expressing cells did not show any reduction in dNTPase activity following PDGF treatment. These data indicate that SAMHD1 oxidation in cells reduces its catalytic activity and that the C522A mutation is resistant to oxidation and therefore maintains catalytic activity following growth factor treatment.

FIG. 5.

SAMHD1 is oxidized in cells in response to growth stimuli. (A) Oxidized proteins in PC3, RWPE, and WI-38 cells stimulated with LPA, R1881, and PDGF, respectively, were labeled with DCP-Bio1 and isolated with streptavidin beads. Captured protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE, blotted onto nitrocellulose, and probed with α-SAMHD1 antibodies. SAMHD1 oxidation increases poststimulation. Oxidized SAMHD1 and total SAMHD1 in the lysate are indicated. AhpC was used as a procedural control. Uncropped images of gels shown in Supplementary Figure S10. (B) Molecular colocalization of SAMHD1 and protein oxidation was visualized using a proximity ligation assay as described. The oxidized species of SAMHD1 (red signal) are present outside the nucleus. (C) On stimulation with LPA, total SAMHD1, imaged by immunofluorescence, moves outside the nucleus over time and colocalizes with areas of oxidized proteins labeled by DCP-Rho1. The mean fluorescence intensity of DAPI, cytoplasmic SAMHD1, and DCP-Rho1 was measured in about 100 cells at each time point, showing an increase in cytoplasmic SAMHD1. Manders' correlation coefficient representing the fraction of total cytoplasmic DCP-Rho1 that colocalizes with pixels containing SAMHD1 signal indicates an increasing colocalization of SAMHD1 with DCP-Rho1. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DCP-Bio1, dimedone coupled probe to biotin; DCP-Rho1, dimedone coupled probe to rhodamine; LPA, lysophosphatidic acid; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor.

We also performed fluorescence microscopy experiments to investigate the oxidation of SAMHD1 in cells. These experiments provided visual evidence of the spatial localization of SAMHD1 and oxidized proteins following the application of ROS-inducing growth factors. PC3 cells treated with LPA and labeled with DCP-Bio1 were imaged using a proximity ligation assay (PLA). In the PLA, fixed cells are incubated with anti-SAMHD1 antibodies and antibiotin antibodies. Secondary antibodies covalently linked to half of a reporter construct are then added and the signal is amplified. A fluorescent signal is observed in sites where both SAMHD1 and labeled cysteines are in proximity, implying that the oxidized protein is SAMHD1. Following LPA incubation in PC3 cells, the fluorescence intensity increases 1.4 × over the control samples at the 10-min time point and gradually diminishes through the 60-min time point (Fig. 5B). These results provide further evidence of SAMHD1 oxidation in vivo, as well as localize the oxidation of protein to the cytoplasm. However, it is unclear if oxidation of SAMHD1 is the cause of protein localization or if it happens in the cytoplasm after relocalization.

A similar experiment was performed using immunofluorescent microscopy to visualize SAMHD1 colocalization with sites of oxidation. PC3 cells were treated as indicated, and cysteine-SOH labeled with a dimedone-based probe conjugated to the fluorophore rhodamine (DCP-Rho1). Cells were fixed and probed with an anti-SAMHD1 antibody and stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Statistical analysis of these cells using colocalization software reveals a correlation between SAMHD1 and DCP-Rho1 (a marker for cysteine sulfenic acid) that peaks at 30 min (Fig. 5C). In addition, we noticed a peculiar trend in SAMHD1 localization at the different time points. While SAMHD1 has previously been reported to be a nuclear protein (5), these experiments show that the distribution of SAMHD1 is varied, implying that an intracellular trafficking event occurs. SAMHD1 is initially observed in the nucleus in the control samples, but following LPA stimulation, it translocates to the cytosol where it overlaps with sites of oxidation, before eventually returning to the nucleus at the 60-min time point. The trafficking of SAMHD1 within the cell follows a similar time course to the oxidation of SAMHD1 in response to a proliferative signal. Taken together, the cellular imaging experiments localize SAMHD1 and oxidized proteins, both temporally and spatially, to occupying similar regions in the cytosol following growth factor stimulation.

Discussion

The connection between SAMHD1 and viral infection has driven much of the initial research efforts into understanding the enzyme's unique structure and dNTPase activity. Given the importance of nucleic acid metabolism to cellular homeostasis throughout the cell cycle, the role SAMHD1 plays in nonpathophysiological cell processes may comprise a more primary biological function. Here we investigate the relationship between SAMHD1 dNTPase activity and the emerging field of redox signaling, suggesting oxidation status as an essential regulator of cell cycle progression.

Our data reveal that SAMHD1 catalytic activity is sensitive to reversible redox regulation in vitro. Oxidation of SAMHD1 interferes with its ability to oligomerize and form an activated tetrameric state. We also demonstrate that SAMHD1 is oxidized in different cell types in response to proliferative signals for each cell type. While the present study and previously reported structural data suggest that oxidation results in a disulfide bond between Cys341 and Cys350, ultimately the ability to respond to redox signals is controlled by Cys522. Mutation of Cys522 to alanine renders SAMHD1 resistant to oxidative inactivation.

Based on these data, we propose a model of oxidative inactivation of SAMHD1 that utilizes Cys522 as a “cysteine switch.” Cysteine switches can adopt different forms, but functionally exist as a mechanism that can translate redox signals into binary on/off structural configurations within enzymes (16, 26). Within the SAMHD1 monomer/dimer, Cys522 resides on a peripheral flexible loop adjacent to the regulatory nucleotide binding site (Fig. 6A). On exposure to a cellular oxidant, such as H2O2, we propose that Cys522 undergoes S-sulfenylation. The flexibility of the loop could allow the oxidized Cys522 to react with the thiol group of either Cys341 or Cys350 to form a disulfide linkage. The formation of the disulfide bond between Cys522 and Cys341 or Cys350 results in a structural rearrangement at the regulatory nucleotide binding site, in which Lys523 is not able to stabilize the γ-phosphate groups of the activating nucleotides. In addition, oxidation of SAMHD1 appears to result in subtle structural shifts within the regulatory region of the enzyme, specifically in relation to α-helices 12 and 13 and the β-sheets on which Cys341 and Cys350 reside. These structural events likely render SAMHD1 incapable of binding the activating nucleotides essential for SAMHD1 tetramerization and subsequent catalytic activation. Oxidation does appear to affect the dimer interface of SAMHD1 or the enzyme's ability to form a dimer, which aligns with structural observations. Given the preponderance of data that identify Cys341-Cys350 as the primary disulfide following oxidation, our model proposes a further thiol–disulfide exchange to generate Cys341-Cys350 and reduce Cys522. Formation of the Cys341-Cys350 disulfide appears to maintain a conformational change in α-helices 12 and 13, which comprise parts of the regulatory nucleotide binding site and tetramer interface, and likely stabilizes the inactive species of SAMHD1. Reduction of the Cys341-Cys350 disulfide by cellular reductants could regenerate the enzyme to complete a multistep regulatory cycle.

FIG. 6.

Model for SAMHD1 regulation by oxidation and cell proliferation. (A) Cys522 is positioned in a flexible loop region adjacent to the regulatory nucleotide binding pocket. Flexibility of the loop might allow oxidized Cys522 to interact with Cys341 or Cys350 to form a disulfide linkage, followed by a resolution to a Cys341-Cys350 disulfide. It is likely that this conformation prevents proper tetramerization of SAMHD1 and therefore inhibits catalytic activity. (B) Proposed model for regulation of SAMHD1 activity by oxidation to regulate cell cycle progression.

Reversible protein oxidation is emerging as a crucial regulatory pathway for essential cellular processes such as cell cycle progression and cell proliferation (6, 24). The data presented in this study implicate nucleotide metabolism as another integral process subject to changes in the cellular redox state, and SAMHD1 as a key arbiter between changes in redox state and nucleotide concentrations. We demonstrate the presence of oxidized SAMHD1 in cells following proliferative signals, which likely results in an increase in the intracellular dNTP pools (Fig. 6B). This is a prerequisite step for DNA replication during S-phase in which high concentrations of dNTPs are necessary (43). We also observe a translocation of SAMHD1 from the nucleus to the cytosol following stimulation with growth factor and colocalization with sites of oxidation. This raises the possibility that oxidation not only affects catalytic activity but also cellular localization, either directly or indirectly by priming the enzyme for additional posttranslational modifications. An additional line of inquiry revealed by this study will be related to how the redox status of SAMHD1 affects its activity in states of pathophysiological stress. Cancer cells maintain higher levels of oxidation (38, 50) than normal cells and certain innate immune signals can initiate an oxidative signaling burst similar to proliferative signals (41, 49). Thus, given the important role SAMHD1 plays in innate immunity and its connection to certain cancers, this represents a rich field of potential research.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and antibodies

Primary antibodies for Western blots to SAMHD1 were from Sigma-Aldrich. Biotin-HRP antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Antibody to Salmonella typhimurium AhpC was purified from rabbit serum. Alexa Fluor fluorescent secondary antibodies and RPMI 1640 medium were from Invitrogen. Fetal bovine serum was from Lonza. Nitrocellulose membranes were from Schleicher and Schuell and Super Signal chemiluminescence reagent was from Pierce. Alkyl-linked 18:1 LPA [1-(9Z-octadecenyl)-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (ammonium salt)] was from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. DCP-Bio1 and DCP-Rho1 were obtained from Dr. Bruce King (Wake Forest University, Department of Chemistry).

SAMHD1 expression and purification

The full-length human SAMHD1 gene was amplified using PCR and cloned into a modified pET28 expression vector (pLM303-SAMHD1) that contained an N-terminal MBP tag and an intervening rhinovirus 3C protease cleavage site. Cysteine to alanine mutations (C320A, C341A, C350A, C522A, and C341-350A) were synthesized and sequenced by GenScript, using the pLM-SAMHD1 expression vector as a template. Expression constructs were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21* and grown in Luria–Bertani medium at 37°C with shaking to an OD600 = 0.6. Cultures were induced with 0.3 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG), rapidly cooled on ice to 20°C, and then allowed to express for 16–18 h at 16°C. Harvested cells were resuspended in amylose column buffer (ACB) (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA], 2 mM DTT, and 5% glycerol) and lysed using an Avestin Emulsiflex-C5 cell homogenizer. Cell debris was cleared by centrifuging at 18.5K rpm for 30 min at 4°C, and the cleared lysate was passed over amylose high flow resin (New England Biolabs) and washed with three column volumes of ACB +2 M NaCl to remove residual nucleic acid. Bound MBP-SAMHD1 was eluted over a linear gradient with ACB +20 mM maltose. The desired fractions were pooled and dialyzed overnight against heparin column buffer (HCB) (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, and 5% glycerol). PreScission Protease (GE Biosciences) was added (100:1) to the MBP-SAMHD1 dialysate to cleave the MBP tag. The SAMHD1 containing sample was separated from the cleaved MBP using a 5 ml Heparin HiTrap (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and eluted using a linear gradient of HCB +2 M NaCl. SAMHD1 containing fractions were again pooled and further purified using Superdex 200 size exclusion chromatography column equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, and 5% glycerol. The protein was concentrated, flash frozen in individual aliquots using liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until use.

SAMHD1 deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase activity assay

Individual protein aliquots were thawed and passed through a microspin column packed with BioGel-P6 (BioRad) and equilibrated with 50 mM NaH2PO4 pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 2% glycerol, to remove all reducing agents from the sample. The concentration of SAMHD1 containing samples was then determined using a NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific) and the extinction coefficient of fully reduced SAMHD1 (ɛ = 75750 M−1 cm−1, A280). In assays investigating the reversible effect of oxidation on SAMHD1 dNTPase activity, unless preincubation with activating nucleotides (100 μM dATPαS-GTP) is indicated, SAMHD1 was first incubated with H2O2 at the specified concentrations for 30 min at 21°C. Where indicated, catalase (100 U) was added to scavenge H2O2. Reducing agents were then added to the designated samples and allowed to incubate at 21°C for 30 min (DTT/TCEP: 10/2 mM or 2/0.4 mM; reduced glutathione: 2 mM; L-cysteine: 2 mM; thioredoxin/thioredoxin reductase/NADPH: 10/0.1/100 μM). DTT and TCEP were used simultaneously to ensure reducing conditions were maintained. Following reduction, treated enzyme samples were mixed with a reaction buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 μM EDTA), and the dNTPase assays were initiated by the addition of 500 μM dATP and 50 μM GTP. Formation of dA was used to measure the progress of the reaction. SAMHD1 concentration in all reactions was 500 nM. Reactions were quenched using EDTA to a final concentration of 10 mM after 10 min.

dNTPase reaction products were analyzed using ion pair reverse phase chromatography on a Waters HPLC system. A CAPCell PAK C18 column (Shiseido Fine Chemicals) was equilibrated with 20 mM NaH2PO4 pH 7.0, 5 mM tetra n-butyl ammonium phosphate, and 5% methanol. Reactants and products were eluted with a linear gradient of methanol from 5% to 50%. A254 was used to measure eluant peaks, and quantification was performed using the Empower Software to integrate the area under each reaction component peak. Data analysis and curve fitting were performed using SigmaPlot v13 (Systat Software, Inc.). The Hanes–Woolf plot was generated by fitting data to the equation:  .

.

SAMHD1 kinetic analyses

SAMHD1 kinetic analyses were performed in a manner similar to dNTPase activity assays with several notable exceptions. SAMHD1 concentration in kinetic assays was reduced to 250 nM, and the enzyme was preactivated with 100 μM GTP-dATPαS before the addition of dGTP substrate. This ensured that steady-state conditions were achieved even at lower concentrations of dGTP. dGTP was chosen in place of dATP as a substrate due to its distinct HPLC peak observed under the specific analytical conditions.

Dynamic light scattering

SAMHD1 particle size distributions as a function of DH were determined under varying oxidative states as well as in the presence of activating nucleotides using a Malvern Nano-S Zetasizer (Malvern Instruments). Reducing agent was removed from recombinant protein using a microspin column packed with BioGel-P6 and equilibrated with the DLS buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4 pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2). Samples were prepared by incubating SAMHD1 with activating nucleotides (100 μM dATPαS-GTP), H2O2 (100 molar equivalents), and a reducing agent(s) (10 mM DTT/2 mM TCEP), or an indicated combination of the three, in a specific order. SAMHD1 final concentration in the samples was 0.2 mg/ml. Raw intensity weighted data were converted to volume% distribution to mitigate the impact of small amounts of aggregated protein.

Circular dichroism

SAMHD1 was transferred to CD buffer (20 mM NaH2PO4 pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2) using a microspin column packed with BioGel-P6 and diluted to 0.2 mg/ml. CD spectra were acquired using a Jasco J-720 Circular Dichroic Spectrometer. Samples were scanned at 21°C from 190 to 250 nm, at pitch of 1 nm, and a speed of 2 nm/min.

Mass spectrometry

SAMHD1 was incubated with TCEP immobilized reducing gel (Pierce) at 21°C for 1 h before sample preparation to reduce any disulfide bonds formed during protein purification. SAMHD1 was transferred into the reaction buffer (50 mM Tris pH7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA) using a microspin column packed with BioGel-P6. One hundred microliters of reaction was prepared by mixing SAMHD1 with dimedone (5 mM), DTT/TCEP (1/0.2 mM) when designated, and the indicated concentration of H2O2. In experiments investigating the presence of disulfide bonds, dimedone was omitted from the reaction. Reactions were allowed to proceed for 180 min (dimedone labeling) or 30 min (disulfide formation) before the protein was partially denatured using 0.1% SDS and free thiols alkylated using 5 mM iodoacetamide. The alkylation reaction was quenched after 60 min by passing the samples through a microspin column packed with Biogel P-6 and equilibrated with a volatile buffer (40 mM NH4HCO3 pH 8.1, 1 mM CaCl2, and 10% acetonitrile). Protein samples were digested with modified trypsin (sequencing grade, Thermo; 1:100) overnight at 37°C. The tryptic peptides were dried using a SpeedVac and resuspended in 5% acetonitrile and 1% formic acid. Five micrograms of protein was analyzed using an LC-MS/MS system that consisted of a Q Exactive HF Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) and a Dionex Ultimate-3000 nano-UPLC system (Thermo Scientific) using a Nanospray Flex Ion Source (Thermo Scientific). An Acclaim PepMap 100 (C18, 5 μm, 100 Å, 100 μm × 2 cm) trap column and an Acclaim PepMap RSLC (C18, 2 μm, 100 Å, 75 μm × 15 cm) analytical column were used for the stationary phase. Good chromatographic separation was observed with a 90-min linear gradient consisting of mobile phases A (5% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid) and B (80% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid). MS spectra were searched using the SEQUEST search algorithm with Proteome Discoverer v2.1 (Thermo Scientific). Search parameters were as follows: FT-trap instrument, parent mass error tolerance of 10 ppm, fragment mass error tolerance of 0.02 Da (monoisotopic), variable modifications on methionine of oxidation, cysteine of alkylation, oxidation, and dimedone. MS spectra were searched for the presence of disulfide bonds using Mass Matrix (57) and pLink-SS (35) software.

Cell culture and treatments

PC3 cells (from ATCC stocks) were grown, maintained, and treated at 37°C with 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, L-glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin. RWPE-1 (from ATCC stocks) cells were grown in keratinocyte serum-free media supplemented with 0.05 mg/ml bovine pituitary extract and 5 ng/ml epidermal growth factor. WI-38 and CCD-1070SK cells (from ATCC stocks) were grown in EMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum, L-glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin. LPA (Avanti), supplied in chloroform, was dried under a stream of nitrogen, resuspended to a concentration of 1 mM in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), and then diluted into culture medium to the indicated concentrations. Full-length human SAMHD1 wild type and C522A containing an N-terminal HA tag were cloned into the eukaryotic expression vector pCDNA3.1. Synthesis and sequencing were performed by GenScript.

Western blotting

For Western blotting, cells were plated at 5 × 105 cells per dish in 100-mm dishes, treated or not with pharmacological agents, washed with cold, calcium-free PBS, scraped into lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 50 mM NaF, and 1 mM sodium vanadate), and centrifuged to remove cell debris after one freeze/thaw cycle. Protein concentration was measured (Pierce BCA protein assay) and samples (typically 40 μg protein/lane) were resolved on SDS polyacrylamide gels, then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, probed with protein-specific antibodies, and visualized using Super Signal chemiluminescence reagent.

Nonreducing Western blotting

Samples were prepared by adding in specific order, fill buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 2% glycerol), activating nucleotides (dATPαS-GTP) as indicated, enzyme as indicated (0.02 mg/ml), and then incubated at room temperature (RT) for 5 min to form the SAMHD1 tetramer in samples with dNTPs added. H2O2 was titrated as indicated (1–100 μM) followed immediately by reducing agent as indicated (10 mM DTT/2 mM TCEP). Samples were incubated at RT for 20 min before adding 100 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to block unreacted cysteines. SAMHD1 protein was diluted to 0.1 μg using a nonreducing SDS sample buffer, resolved by 7% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, probed for SAMHD1, and visualized using Super Signal chemiluminescence reagent.

DCP-Bio1 labeling and affinity capture

Cells (∼5 × 105) were grown in 100-mm plates for 48 h as described above, and after incubation of 100 nM alkyl-LPA with the cells for indicated time points, DCP-Bio1 was added with the lysis buffer to chemically trap sulfenic acid proteins as described by Klomsiri et al. (27) with slight modifications. Lysis buffer was freshly prepared and supplemented with 1 mM DCP-Bio1, 10 mM NEM, 10 mM iodoacetamide, and 200 U/ml catalase. Use of NEM and iodoacetamide together provided the best blocking of free thiols. Lysis buffer (150 μl/plate) was added to each plate, then cells were scraped from the plates, transferred to Eppendorf tubes, and incubated on ice for 30 min before storing at −80°C. For affinity capture and elution of the labeled proteins, unreacted DCP-Bio1 was removed immediately on thawing using a BioGel P6 spin column. Samples were then assayed for protein concentration, diluted to 1.0 mg/ml protein into 400 μl buffer containing a final concentration of 2 M urea, and supplemented with pre-biotinylated AhpC (0.5 μg/400 μg of total lysate) to control for the efficiency of the affinity capture and elution procedures. Samples were precleared with Sepharose CL-4B beads (Sigma), applied to columns containing high-capacity streptavidin–agarose beads from Pierce, and then incubated overnight at 4°C. Multiple stringent washes of the beads were performed (at least four column volumes and two washes each) using, in series, 1% SDS, 4 M urea, 1 M NaCl, 10 mM DTT, 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate and water, before elution with Laemmli sample buffer (27). Samples were stored at −80°C as needed and analyzed by Western blot as described above. Alternatively, samples lysed in the presence of DCP-Bio1 were immunoprecipitated using the SAMHD1 antibody and Pierce protein A/G magnetic beads according to the manufacturer's protocol. Proteins were eluted from the beads using SDS-sample buffer containing beta-mercaptoethanol and detected by Western blotting.

Immunofluorescence

For immunofluorescence studies, 4 × 104 cells were plated in 0.5 ml of media in four-well chambered cover glass, incubated for 24 h, and then treated (or not) with LPA for indicated time points; DCP-Rho1 at 10 μM was added for the final 10 min of LPA stimulation (28), and then cells were washed extensively with RPMI containing 10% fetal bovine serum before fixing with 10% formalin for 15 min. Cells were washed three times with 0.1 mM glycine in PBS containing 2% fetal bovine serum and then permeabilized for 10 min with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS-T. After washing three times with PBS-T, samples were blocked with 2% BSA in PBS-T for 1 h and then incubated with primary antibodies (1:200 dilution) overnight at 4°C in 2% BSA in PBS-T. After washing with PBS-T, Alexa Fluor-labeled secondary antibodies diluted 1:1000 were added and incubated for 2 h at RT, and washed again with PBS-T. Chambers were removed, coverslips were mounted using ProLong Gold Antifade Reagent with DAPI (Molecular Probes), incubated for 18 h, and then imaged. Labeled cells were visualized by confocal microscopy using an Olympus FV 1200 Spectral Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope. A goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor488 secondary antibody with excitation at 488 nm and emission at 505–550 nm was used for imaging of SAMHD1. Excitation at 561 nm and emission at 566–703 nm was used for the DCP-Rho1 signal. Intensity values were kept in the linear range, and the absence of crossover and bleed through between channels was confirmed as described in Klomsiri et al. (28). Image analysis was performed using the Fiji image processing software and the coloc2 plugin (46). An intensity threshold was manually determined on a control image and identically applied to all images to correct for background signal. The cytoplasmic fraction was isolated by subtracting the DAPI signal from images converted to gray scale for analysis. Manders' coefficients (11) represent the fraction of the total summed intensities (i) for a fluorescent probe, R, that colocalizes with pixels containing intensities for a second probe, G, as described by the equation:

Proximity ligation assay

PC3 cells (∼5 × 105 per well) were plated on a four-well chambered slide and incubated 48 h before stimulating with LPA as indicated. DCP-Bio1 was added at a concentration of 10 μM for the final 10 min of LPA stimulation. Cells were rinsed with growth media three times and one time with PBS before incubating 10 min in 10% formalin containing 10 mM NEM and 10 mM iodoacetamide. After fixation, cells were rinsed three times with PBS-T containing 2% FBS and 0.1 M glycine. Cells were permeabilized with 0.1% TritionX-100 in PBS-T for 10 min, washed with PBS-T, and then blocked for 1 h with 2% BSA in PBS-T. Primary antibodies against SAMHD1 and Biotin (1:200 dilution) were added overnight in blocking buffer. After washing in PBS-T, PLA probes from the Duolink In Situ Red Starter Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) were added to cells, and the ligation reaction was done according to the manufacturer's instructions. Amplification of the PLA signal was done using the supplied red amplification buffer and polymerase as per instructions. Cells were mounted in Duolink In Situ Mounting Medium containing DAPI and visualized by confocal microscopy using an Olympus FV 1200 Spectral Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope. Excitation at 561 nm and emission at 566–703 nm were used for the PLA signal. Intensity values were kept in the linear range, and the absence of crossover and bleed through between channels was confirmed as described in Klomsiri et al. (28). ImageJ software was used to quantify mean fluorescence intensity of at least 100 cells per time point.

Cell lysate dNTPase assay

CCD-1070SK fibroblasts (0.25 × 106 cells) were plated in 100-mm dishes in 10 ml of media. Twenty-four hours after seeding, cells were transiently transfected using FuGENE® HD Transfection Reagent (Promega) with pCDNA3.1 vectors containing wild-type SAMHD1, C522A mutant SAMHD1, or an empty vector control. Before experimental treatment, cells were incubated in serum-free media for 24 h. Seventy-two hours post-transfection, PDGF (or an equivalent volume of PBS) was added to the dishes to a final concentration of 20 nM. Treated and control cells were washed with cold PBS 60 min post-treatment, harvested by trypsinization, pelleted, and lysed in 100 μl of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.05% NP-40, 1% Triton-X, 100 μM PMSF, 200 U/ml catalase, 10 ng/ml aprotinin, and 10 ng/ml leupeptin). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 10000 rcf for 10 min and protein content for each sample determined using a BCA assay. One hundred micrograms of protein was then used to conduct a dNTPase assay as described above, varying only by substrate (1 mM dGTP) and time (5 h), given the relatively small amount of SAMHD1 within each sample. Reactions were quenched using EDTA to a final concentration of 25 mM, boiled for 1 min, and centrifuged at 15000 rcf for 10 min to remove protein. The supernatant was then analyzed by HPLC, and reaction progress determined by the relative integrated areas under the dG and dGTP peaks.

Size exclusion chromatography: multiangle light scattering

Purified recombinant SAMHD1 was passed through a microspin column containing BioGel-P6 (BioRad) equilibrated with analytical size exclusion buffer (ASEC) (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 100 μM EDTA) to remove all reducing agents from the protein. SAMHD1 at 2.0 mg/ml was treated with H2O2 (250 μM) for 30 min, H2O2, and then reducing agent (10 mM DTT/2.5 mM TCEP), or ASEC buffer alone, before tetramerization was induced by the addition of dGTPαS (250 μM). One hundred microliters of each sample was then injected onto an analytical size exclusion TSKgel column (7.8 mm × 30 cm, 8 μm particle size; Tosoh Bioscience) equilibrated with SEC buffer and run at 0.5 ml/min. Elution profiles were monitored by UV280 absorbance (2998 Photodiode Array Detector; Waters) and molecular masses determined by multiangle light scattering (HELEOS II; Wyatt Technology) with linked refractive index determination (Optilab rEX; Wyatt Technology). Astra 6.1 software (Wyatt Technology) was used to analyze experimental data and generate figures.

Glutaraldehyde crosslinking

Recombinant SAMHD1 wild-type or C522A mutant was passed through a microspin column containing BioGel-P6 (BioRad) equilibrated with crosslinking buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4 pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 100 μM EDTA, 2% glycerol). One hundred microliters of reaction was set up containing 2.5 μg of protein sequentially treated with the indicated combination of activating nucleotides (200 μM dGTPαS), H2O2 for 10, 20, or 30 min, and reducing agent (10 mM DTT/2 mM TCEP). Glutaraldehyde was then added to a final concentration of 2.5 mM and the crosslinking allowed to proceed for 10 min at 21°C before quenching with 100 μl of 0.5 M Tris/0.5 M Glycine. Protein samples were separated using 4–12% SDS-PAGE and imaged by Western blot. Densitometry analysis of the relative intensity of bands corresponding to the monomer, dimer, and tetramer species was performed using Fiji software.

Data and statistical analysis

Charts and graphs were generated using SigmaPlot v13.0, which was also used for statistical analysis, t-test comparisons, and nonlinear regression. Statistical significance was determined at three levels of significance; p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***). Molecular representations were generated using the program PyMOL (47).

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- ASEC

analytical size exclusion buffer

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CD

circular dichroism

- Cys

cysteine

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- dATPαS

deoxyadenosine triphosphate alpha S

- DCP-Bio1

dimedone coupled probe to biotin

- DCP-Rho1

dimedone coupled probe to rhodamine

- DH

hydrodynamic diameter

- DLS

dynamic light scattering

- dNTP

deoxynucleotide triphosphate

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- GTP

guanosine triphosphate

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- IPTG

isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside

- LPA

lysophosphatidic acid

- NEM

N-ethylmaleimide

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PBS-T

phosphate-buffered saline, 0.1% Triton X-100

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- PLA

proximity ligation assay

- PMSF

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- R-SO2H

sulfinic acid

- R-SO3H

sulfonic acid

- R-SOH

sulfenic acid

- RT

room temperature

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SEC-MALS

size exclusion chromatography-multiangle light scattering

- TCEP

tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jingyun Lee and the staff of the Metabolomics and Proteomics Shared Resource of the Wake Forest School of Medicine for their assistance in the performance and analysis of mass spectrometry experiments, and Amy Molan and Michael Carpenter for comments on the article. This work has been supported through funding from the NIH (RO1 GM108827 to T.H., RO1 CA142838 to L.W.D., R01 GM06692 to F.W.P., and R33 CA177461 to L.B.P., and T32 GM095440 support for C.H.M.), Alliance for Lupus Research to F.W.P., and the Comprehensive Cancer Center of Wake Forest University National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA012197. R.S.H. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Authors' Contributions

Conceptualization: C.H.M., L.C.R., R.S.H., L.W.D., F.W.P., T.H.; Methodology: C.H.M., L.C.R., C.M.F., L.B.P., H.W., T.H.; Investigation: C.H.M., L.C.R., N.O.D-B. H.W.; Writing—original draft: C.H.M., L.C.R., T.H.; Writing—review and editing: C.H.M., L.C.R., R.S.H., L.W.D., L.B.P., F.W.P., T.H.; Supervision: T.H., F.W.P., R.S.H., C.M.F.; Funding Acquisition: T.H., F.W.P., R.S.H., C.M.F., L.W.D., L.B.P.

Author Disclosure Statement

All of the authors declare they have no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, that influenced the data collection, interpretation, or publication of this work.

References

- 1.Amie SM, Bambara RA, and Kim B. GTP is the primary activator of the anti-HIV restriction factor SAMHD1. J Biol Chem 288: 25001–25006, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnold L, Groom HC, Kunzelmann S, Schwefel D, Caswell S, Ordonez P, Mann M, Rueschenbaum S, Goldstone D, Pennell S, Howell S, Stoye J, Webb M, Taylor I, and Bishop KN. Phospho-dependent regulation of Samhd1 oligomerisation couples catalysis and restriction. PLoS Pathog 11: 5194, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldauf H-M, Pan X, Erikson E, Schmidt S, Daddacha W, Burggraf M, Schenkova K, Ambiel I, Wabnitz G, Gramberg T, Panitz S, Flory E, Landau NR, Sertel S, Rutsch F, Lasitschka F, Kim B, König R, Fackler OT, and Keppler OT. SAMHD1 restricts HIV-1 infection in resting CD4+ T cells. Nat Med 18: 1682–1689, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonifati S, Daly MB, St. Gelais C, Kim SH, Hollenbaugh JA, Shepard C, Kennedy EM, Kim D-H, Schinazi RF, Kim B, and Wu L. SAMHD1 controls cell cycle status, apoptosis and HIV-1 infection in monocytic THP-1 cells. Virology 495: 92–100, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandariz-Nunez A, Valle-Casuso JC, White TE, Laguette N, Benkirane M, Brojatsch J, and Diaz-Griffero F. Role of SAMHD1 nuclear localization in restriction of HIV-1 and SIVmac. Retrovirology 9: 49, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burhans WC. and Heintz NH. The cell cycle is a redox cycle: linking phase-specific targets to cell fate. Free Radic Biol Med 47: 1282–1293, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clifford R, Louis T, Robbe P, Ackroyd S, Burns A, Timbs AT, Wright Colopy G, Dreau H, Sigaux F, Judde JG, Rotger M, Telenti A, Lin YL, Pasero P, Maelfait J, Titsias M, Cohen DR, Henderson SJ, Ross MT, Bentley D, Hillmen P, Pettitt A, Rehwinkel J, Knight SJL, Taylor JC, Crow YJ, Benkirane M, and Schuh A. SAMHD1 is mutated recurrently in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and is involved in response to DNA damage. Blood 123: 1021–1031, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cremers CM. and Jakob U. Oxidant sensing by reversible disulfide bond formation. J Biol Chem 288: 26489–26496, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cribier A, Descours B, Valadão A, Laguette N, and Benkirane M. Phosphorylation of SAMHD1 by cyclin A2/CDK1 regulates its restriction activity toward HIV-1. Cell Rep 3: 1036–1043, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crow YJ. and Rehwinkel J. Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome and related phenotypes: linking nucleic acid metabolism with autoimmunity. Hum Mol Genet 18: R130–R136, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn KW, Kamocka MM, and McDonald JH. A practical guide to evaluating colocalization in biological microscopy. AJP Cell Physiol 300: C723–C742, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finkel T. Signal transduction by reactive oxygen species. J Cell Biol 194: 7–15, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franzolin E, Pontarin G, Rampazzo C, Miazzi C, Ferraro P, Palumbo E, Reichard P, and Bianchi V. The deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase SAMHD1 is a major regulator of DNA precursor pools in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: 14272–14277, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furdui CM. and Poole LB. Chemical approaches to detect and analyze protein sulfenic acids. Mass Spectrom Rev 33: 126–146, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Go Y-M, Chandler JD, and Jones DP. The cysteine proteome. Free Radic Biol Med 84: 227–245, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Go Y-M. and Jones DP. The redox proteome. J Biol Chem 288: 26512–26520, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstone DC, Ennis-Adeniran V, Hedden JJ, Groom HC, Rice GI, Christodoulou E, Walker PA, Kelly G, Haire LF, Yap MW, de Carvalho LP, Stoye JP, Crow YJ, Taylor IA, and Webb M. HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 is a deoxynucleoside triphosphate triphosphohydrolase. Nature 480: 379–382, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gramberg T, Kahle T, Bloch N, Wittmann S, Müllers E, Daddacha W, Hofmann H, Kim B, Lindemann D, and Landau NR. Restriction of diverse retroviruses by SAMHD1. Retrovirology 10: 26, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansen EC, Seamon KJ, Cravens SL, and Stivers JT. GTP activator and dNTP substrates of HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 generate a long-lived activated state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: E1843–E1851, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollenbaugh JA, Gee P, Baker J, Daly MB, Amie SM, Tate J, Kasai N, Kanemura Y, Kim D-H, Ward BM, Koyanagi Y, and Kim B. Host factor SAMHD1 restricts DNA viruses in non-dividing myeloid cells. PLoS Pathog 9: e1003481, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hrecka K, Hao C, Gierszewska M, Swanson SK, Kesik-Brodacka M, Srivastava S, Florens L, Washburn MP, and Skowronski J. Vpx relieves inhibition of HIV-1 infection of macrophages mediated by the SAMHD1 protein. Nature 474: 658–661, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji X, Tang C, Zhao Q, Wang W, and Xiong Y. Structural basis of cellular dNTP regulation by SAMHD1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014: 1–10, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ji X, Wu Y, Yan J, Mehrens J, Yang H, DeLucia M, Hao C, Gronenborn AM, Skowronski J, Ahn J, and Xiong Y. Mechanism of allosteric activation of SAMHD1 by dGTP. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20: 1304–1309, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones DP. Redox sensing: orthogonal control in cell cycle and apoptosis signalling. J Intern Med 268: 432–448, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim B, Nguyen LA, Daddacha W, and Hollenbaugh JA. Tight interplay among SAMHD1 protein level, cellular dNTP levels, and HIV-1 proviral DNA synthesis kinetics in human primary monocyte-derived macrophages. J Biol Chem 287: 21570–21574, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klomsiri C, Karplus PA, and Poole LB. Cysteine-based redox switches in enzymes. Antioxid Redox Signal 14: 1065–1077, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klomsiri C, Nelson KJ, Bechtold E, Soito L, Johnson LC, Lowther WT, Ryu S-E, King SB, Furdui CM, and Poole LB. Use of dimedone-based chemical probes for sulfenic acid detection. Thiol Redox Transit Cell Signal Part A 473: 77–94, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klomsiri C, Rogers LC, Soito L, McCauley AK, King SB, Nelson KJ, Poole LB, and Daniel LW. Endosomal H2O2 production leads to localized cysteine sulfenic acid formation on proteins during lysophosphatidic acid-mediated cell signaling. Free Radic Biol Med 71: 49–60, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koharudin LMI, Wu Y, DeLucia M, Mehrens J, Gronenborn AM, and Ahn J. Structural basis of allosteric activation of sterile motif and histidine-aspartate domain-containing protein 1 (SAMHD1) by nucleoside triphosphates. J Biol Chem 289: 32617–32627, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kretschmer S, Wolf C, Konig N, Staroske W, Guck J, Hausler M, Luksch H, Nguyen La, Kim B, Alexopoulou D, Dahl A, Rapp A, Cardoso MC, Shevchenko A, and Lee-Kirsch MA. SAMHD1 prevents autoimmunity by maintaining genome stability. Ann Rheum Dis 74: e17, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laguette N, Sobhian B, Casartelli N, Ringeard M, Chable-Bessia C, Ségéral E, Yatim A, Emiliani S, Schwartz O, and Benkirane M. SAMHD1 is the dendritic- and myeloid-cell-specific HIV-1 restriction factor counteracted by Vpx. Nature 474: 654–657, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lahouassa H, Daddacha W, Hofmann H, Ayinde D, Logue EC, Dragin L, Bloch N, Maudet C, Bertrand M, Gramberg T, Pancino G, Priet S, Canard B, Laguette N, Benkirane M, Transy C, Landau NR, Kim B, and Margottin-Goguet F. SAMHD1 restricts the replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by depleting the intracellular pool of deoxynucleoside triphosphates. Nat Immunol 13: 223–228, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li N, Zhang W, and Cao X. Identification of human homologue of mouse IFN-γ induced protein from human dendritic cells. Immunol Lett 74: 221–224, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu JP, Monardo L, Bryskin I, Hou ZF, Trachtenberg J, Wilson BC, and Pinthus JH. Androgens induce oxidative stress and radiation resistance in prostate cancer cells though NADPH oxidase. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 13: 39–46, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu S, Fan S-B, Yang B, Li Y-X, Meng J-M, Wu L, Li P, Zhang K, Zhang M-J, Fu Y, Luo J, Sun R-X, He S-M, and Dong M-Q. Mapping native disulfide bonds at a proteome scale. Nat Methods 12: 329–331, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pauls E, Ruiz A, Badia R, Permanyer M, Gubern A, Riveira-Muñoz E, Torres-Torronteras J, Alvarez M, Mothe B, Brander C, Crespo M, Menéndez-Arias L, Clotet B, Keppler OT, Martí R, Posas F, Ballana E, and Esté JA. Cell cycle control and HIV-1 susceptibility are linked by CDK6-dependent CDK2 phosphorylation of SAMHD1 in myeloid and lymphoid cells. J Immunol 193: 1988–1997, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paulsen CE. and Carroll KS. Cysteine-mediated redox signaling: chemistry, biology, and tools for discovery. Chem Rev 113: 4633–4679, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Policastro L, Molinari B, Larcher F, Blanco P, Podhajcer OL, Costa CS, Rojas P, and Durán H. Imbalance of antioxidant enzymes in tumor cells and inhibition of proliferation and malignant features by scavenging hydrogen peroxide. Mol Carcinog 39: 103–113, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poole LB. The basics of thiols and cysteines in redox biology and chemistry. Free Radic Biol Med 80: 148–157, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Powell RD, Holland PJ, Hollis T, and Perrino FW. Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome gene and HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 is a dGTP-regulated deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase. J Biol Chem 286: 43596–43600, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Radeke HH, Meier B, Topley N, Flöge J, Habermehl GG, and Resch K. Interleukin 1-α and tumor necrosis factor-α induce oxygen radical production in mesangial cells. Kidney Int 37: 767–775, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ravenscroft JC, Suri M, Rice GI, Szynkiewicz M, and Crow YJ. Autosomal dominant inheritance of a heterozygous mutation in SAMHD1 causing familial chilblain lupus. Am J Med Genet A 155A: 235–237, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reichard P. Interactions between deoxyribonucleotide and DNA synthesis. Annu Rev Biochem 57: 349–374, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rentoft M, Lindell K, Tran P, Chabes AL, Buckland RJ, Watt DL, Marjavaara L, Nilsson AK, Melin B, Trygg J, Johansson E, and Chabes A. Heterozygous colon cancer-associated mutations of SAMHD1 have functional significance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113: 4723–4728, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rice GI, Bond J, Asipu A, Brunette RL, Manfield IW, Carr IM, Fuller JC, Jackson RM, Lamb T, Briggs TA, Ali M, Gornall H, Couthard LR, Aeby A, Attard-Montalto SP, Bertini E, Bodemer C, Brockmann K, Brueton LA, Corry PC, Desguerre I, Fazzi E, Cazorla AG, Gener B, Hamel BCJ, Heiberg A, Hunter M, van der Knaap MS, Kumar R, Lagae L, Landrieu PG, Lourenco CM, Marom D, McDermott MF, van der Merwe W, Orcesi S, Prendiville JS, Rasmussen M, Shalev SA, Soler DM, Shinawi M, Spiegel R, Tan TY, Vanderver A, Wakeling EL, Wassmer E, Whittaker E, Lebon P, Stetson DB, Bonthron DT, and Crow YJ. Mutations involved in Aicardi-Goutières syndrome implicate SAMHD1 as regulator of the innate immune response. Nat Genet 41: 829–832, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez J-Y, White DJ, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, and Cardona A. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9: 676–682, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schrödinger LLC. The {PyMOL} Molecular Graphics System, Version ∼1.8, http://pymol.org Accessed December, 2016

- 48.St. Gelais C, de Silva S, Amie SM, Coleman CM, Hoy H, Hollenbaugh JA, Kim B, and Wu L. SAMHD1 restricts HIV-1 infection in dendritic cells (DCs) by dNTP depletion, but its expression in DCs and primary CD4+ T-lymphocytes cannot be upregulated by interferons. Retrovirology 9: 105, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sundaresan M, Yu ZX, Ferrans VJ, Sulciner DJ, Gutkind JS, Irani K, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, and Finkel T. Regulation of reactive-oxygen-species generation in fibroblasts by Rac1. Biochem J 318 (Pt 2): 379–382, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Szatrowski TP. and Nathan CF. Production of large amounts of hydrogen peroxide by human tumor cells. Cancer Res 51: 794–798, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang J-L, Lu F-Z, Shen X-Y, Wu Y, and Zhao L-T. SAMHD1 is down regulated in lung cancer by methylation and inhibits tumor cell proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 455: 229–233, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Welbourn S, Dutta SM, Semmes OJ, and Strebel K. Restriction of virus infection but not catalytic dNTPase activity is regulated by phosphorylation of SAMHD1. J Virol 87: 11516–11524, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Welbourn S. and Strebel K. Low dNTP levels are necessary but may not be sufficient for lentiviral restriction by SAMHD1. Virology 488: 271–277, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.White TE, Brandariz-Nuñez A, Valle-Casuso JC, Amie S, Nguyen L, Kim B, Brojatsch J, and Diaz-Griffero F. Contribution of SAM and HD domains to retroviral restriction mediated by human SAMHD1. Virology 436: 81–90, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.White TE, Brandariz-Nuñez A, Valle-Casuso JC, Amie S, Nguyen LA, Kim B, Tuzova M, and Diaz-Griffero F. The retroviral restriction ability of SAMHD1, but not its deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase activity, is regulated by phosphorylation. Cell Host Microbe 13: 441–451, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Winterbourn CC. and Hampton MB. Thiol chemistry and specificity in redox signaling. Free Radic Biol Med 45: 549–561, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu H, Hsu P-H, Zhang L, Tsai M-D, and Freitas Ma. Database search algorithm for identification of intact cross-links in proteins and peptides using tandem mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res 9: 3384–3393, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yan J, Kaur S, DeLucia M, Hao C, Mehrens J, Wang C, Golczak M, Palczewski K, Gronenborn AM, Ahn J, and Skowronsk S. Tetramerization of SAMHD1 is required for biological activity and inhibition of HIV infection. J Biol Chem 288: 10406–10417, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhu C, Gao W, Zhao K, Qin X, Zhang Y, Peng X, Zhang L, Dong Y, Zhang W, Li P, Wei W, Gong Y, and Yu XF. Structural insight into dGTP-dependent activation of tetrameric SAMHD1 deoxynucleoside triphosphate triphosphohydrolase. Nat Commun 4: 2722, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu C, Wei W, Peng X, Dong Y, Gong Y, and Yu XF. The mechanism of substrate-controlled allosteric regulation of SAMHD1 activated by GTP. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 71: 516–524, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.