Abstract

Objectives: To investigate the prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use, including botanical/herbal remedies, among Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN), New Jersey site. We also examined whether attitudes toward CAM and communication of its use to providers differed for Hispanic and non-Hispanic women.

Study design: SWAN is a community-based, multiethnic cohort study of midlife women. At the 13th SWAN follow-up, women at the New Jersey site completed both a general CAM questionnaire and a culturally sensitive CAM questionnaire designed to capture herbal products commonly used in Hispanic/Latina communities. Prevalence of and attitudes toward CAM use were compared by race/ethnicity and demographic characteristics.

Results: Among 171 women (average age 61.8 years), the overall prevalence of herbal remedy use was high in both Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women (88.8% Hispanic and 81.3% non-Hispanic white), and prayer and herbal teas were the most common modalities used. Women reported the use of multiple herbal modalities (mean 6.6 for Hispanic and 4.0 for non-Hispanic white women; p = 0.001). Hispanic women were less likely to consider herbal treatment drugs (16% vs. 37.5%; p = 0.005) and were less likely to report sharing the use of herbal remedies with their doctors (14.4% Hispanic vs. 34% non-Hispanic white; p = 0.001). The number of modalities used was similar regardless of the number of prescription medications used.

Conclusions: High prevalence of herbal CAM use was observed for both Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women. Results highlight the need for healthcare providers to query women regarding CAM use to identify potential interactions with traditional treatments and to determine whether CAM is used in lieu of traditional medications.

Keywords: : complementary and alternative medicine, Hispanic women, herbal remedies

Introduction

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use in the United States is widespread. The National Health Interview Survey 2012–20151 found that 34% of U.S. adults reported any CAM use in the past year. CAM is defined as a group of diverse medical healthcare systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine.2 CAM includes herbal medicines, homeopathy, and folk remedies.

While knowledge of a patient's CAM use is critical for optimal care delivery,3 there is little consistent data regarding CAM prevalence in different race/ethnic groups or the extent to which individuals discuss CAM with healthcare providers. Previous studies suggest that when all modalities are considered together, CAM use prevalence is similar by race/ethnicity. However, because the use of specific modalities varies across race/ethnic groups,4,5 estimates of overall CAM use depend upon the specific modalities queried. People of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity use herbal self-care remedies as part of their cultural values and practices and some studies suggest that they may use more herbal remedies than other ethnic groups.6–8 However, prior studies have not considered the heterogeneity of Hispanic women/Latinas from diverse countries of origin. In particular, research studies utilizing general CAM surveys with midlife women may not include botanical/herbal CAM from Latin and Caribbean countries of origin. Many of the most widely used general CAM surveys are more focused on modalities used by individuals from English, North American, and Asian origin.9 Broad categories and terms such as herbal teas may not accurately reflect terminology, phraseology, or regional colloquialisms of practices from Hispanic/Latin countries.9

Nondisclosure of CAM usage to medical care providers is reported to be high, ranging from 23% to 72%.10 In particular, CAM use may be under-reported in minority populations where herbs and spices commonly used for medicinal purposes are not considered to be medications.11–15 Nevertheless, there is little data specifically regarding attitudes toward disclosure of herbal remedies by immigrant Hispanic women and Latinas. Past studies have focused on Mexican herbs and spices or on specific geographical regions not taking into account the variation of herbal/botanical use within Hispanic/Latina cultures.9

Data from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN), New Jersey site, provided the opportunity to examine CAM use prevalence, attitudes toward CAM use, and regarding communicating CAM use to healthcare providers among Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women in a community-based sample. We hypothesize that Hispanic women/Latinas would have a higher frequency of botanical/herbal use relative to non-Hispanic white women and that the use of vitamin supplements and self-care practices would be lower in Hispanic women/Latinas. Furthermore, we hypothesize that Hispanic women/Latinas would be less likely to communicate CAM use to physicians and less likely to consider CAM and herbal remedies as medicines.

Methods

Study population

SWAN is a prospective, multiethnic cohort study of women at seven clinical sites in the United States. Between 1996 and 1997, each site recruited whites and one ethnic minority group. This analysis is based on data from the New Jersey site (Newark, NJ) where white and Hispanic women were recruited. The Hispanic/Latina group includes women who identified as Puerto Rican, Dominican, Cuban, and Central and South American. Women were eligible for SWAN if they were aged 42–52 years and premenopausal or early perimenopausal at baseline. Women who had undergone a hysterectomy or bilateral oophorectomy, were pregnant, or were using hormone replacement therapy or oral contraceptives at baseline were excluded.16 All women signed informed consent following protocols approved by the local institutional review board.

This paper utilizes data from the 13th SWAN follow-up (conducted 2011–2012). Of the 420 (142 non-Hispanic white, 278 Hispanic) women enrolled, 201 participated in the 13th visit. The analysis is based on 171 (64 non-Hispanic white and 171 Hispanic) women who completed both the SWAN core CAM questionnaire, which focuses on CAM practices with a heavy emphasis on Asian medicine, and a site-specific Hispanic/Latina Herbal CAM questionnaire targeting the use of herbal remedies and regarding attitudes toward CAM and communication of CAM use with healthcare providers.

Use of complementary and alternative therapies

SWAN core CAM survey

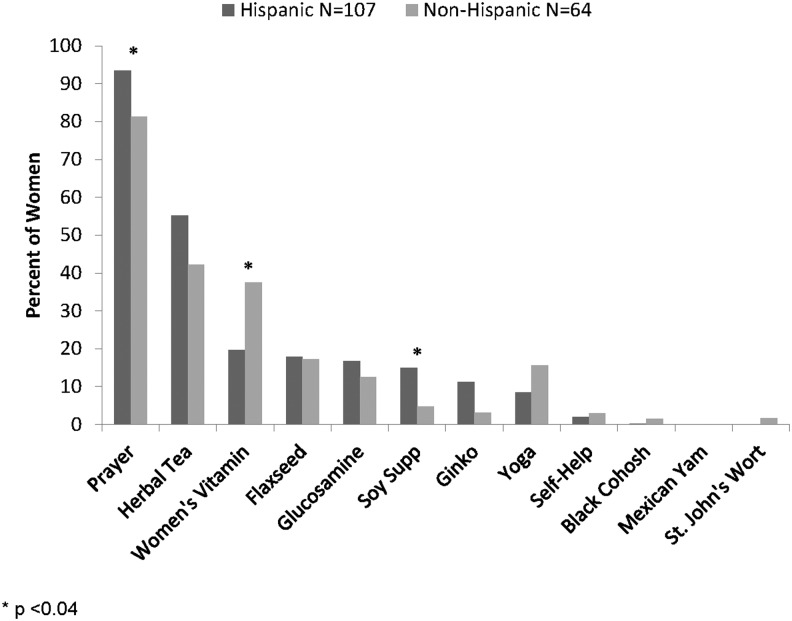

The self-administered SWAN core general CAM questionnaire included a list of 21 CAM modalities separated into three main domains; herbal, spiritual, and physical—herbs or herbal remedies, such as homeopathy or Chinese herbs or teas; special diets or nutritional remedies, such as macrobiotic or vegetarian diets, vitamins, or supplements; psychological or spiritual methods, such as prayer, meditation, mental imagery, or relaxation techniques; physical methods, such as massage, acupressure, or acupuncture; and folk medicine or traditional Chinese medicine. The questionnaire was translated into Spanish by a certified translation service. Women were asked to indicate which modalities they had used in the past 12 months and reasons for their use.17 The modalities included are shown in Figure 1.

FIG. 1.

Frequency of general complementary and alternative medicine use for Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women at Study of Women's Health Across the Nation, New Jersey site, 2011–2013.

Site-specific herbal remedy instrument

Participants at the New Jersey site were invited to complete an additional 48-item survey geared to the use of herbal remedies. The survey was available in both English and Spanish and mailed to participants following the 13th SWAN clinic visit. The 24 herbs included were selected based on available literature regarding the use of botanical herbal remedies in Hispanic and Latino populations from diverse countries of origin.7 The survey asked about herbs commonly used for treatment purposes (not as food or seasonings) taken either orally or mixed in a salve (pomade) or by boiling leaves to make a tea. The herbs were listed in both English and Spanish, along with a picture to provide visual/pictorial and name recognition. The herbs/remedies listed were Aloe Vera, Garlic, Cloves, Ginger, Mint, Dandelions, Fenugreek, Star Anise, Cinnamon, Cumin, Eucalyptus, Lemon, Cat's Claw, Linden, Tea, Bark Whole, Fish Oil, Mistletoe, Oaxaca Herb, Flax Seed, Rose hips, Noni juice, Shark oil, and Greasewood. The questionnaire also included items regarding attitudes and beliefs toward herbal treatments and questions regarding whether respondents discuss herbal treatments with their physician.

Demographic and socioeconomic status variables

Years of education were ascertained at the SWAN baseline and classified as ≤high school or >high school. Financial strain, employment status, health insurance status, number of physician visits in the past year, and medication use were self-reported. Prescription medication use was confirmed by visual inspection of containers. Financial strain was assessed by asking “How hard is it for you to pay for basics? (Very hard, Somewhat hard, or Not hard at all)” and dichotomized as somewhat/very hard versus not hard at all.

Statistical methods

Demographic variables, prevalence of CAM use, and responses to questions regarding attitudes and communication of CAM use were compared for Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women and by demographic characteristics. Comparisons were made using the chi-square test for categorical variables and two-sample t-tests for continuous variables. Analyses were completed using SAS, version 9.4.

Results

Comparison of baseline characteristics for women included and not included in the analysis shows that those in the analysis sample were more likely to have completed high school (52.8% vs. 37.3%) and are less likely to report financial strain (14.7% vs. 24.2%; p < 0.01). The two groups were not significantly different regarding baseline age, whether born in the United States, and the proportion who were Hispanic.

Characteristics of Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women in the analysis population are shown in Table 1. Compared with non-Hispanic white women, Hispanic women were less likely to have completed high school, to be employed, and to have health insurance and were more likely to indicate financial strain. However, the overall frequency of seeing a physician in the past year was not significantly different.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Hispanic and Non-Hispanic Women at Study of Women's Health Across the Nation, New Jersey Site, Visit 13 (2011–2013)

| Hispanic (n = 107) | Non-Hispanic (n = 64) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 62.0 (3.0) | 61.6 (2.6) | 0.36 |

| Education > high school % | 37.8 | 77.1 | 0.0001 |

| Currently working | 49.5 | 68.8 | 0.01 |

| Financial strain | 0.0001 | ||

| (Somewhat or very hard to pay for basics) | 72.6 | 39.1 | |

| Have health insurance | 73.8 | 87.5 | 0.03 |

| Number of times seen a doctor in the past year | 0.21 | ||

| 0 | 5.6 | 10.9 | |

| 1–2 | 35.5 | 25.0 | |

| 3+ | 58.9 | 64.1 |

The prevalence of use for CAM modalities included in the SWAN core CAM questionnaire is shown in Figure 1. Prayer, women's vitamin supplements, and herbal tea were the most frequently reported modalities for both Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women. Few women of either race/ethnic group reported the use of self-help modalities or yoga. Hispanic women were more likely to report the use of prayer for general health (93.5% Hispanic vs. 81.3% non-Hispanic; p = 0.01) and soy supplements (15.0% Hispanic vs. 4.7% non-Hispanic; p = 0.04). In contrast, non-Hispanic white women were more likely to report using women's vitamin supplements (19.6% Hispanic vs. 37.5% non-Hispanic; p = 0.01).

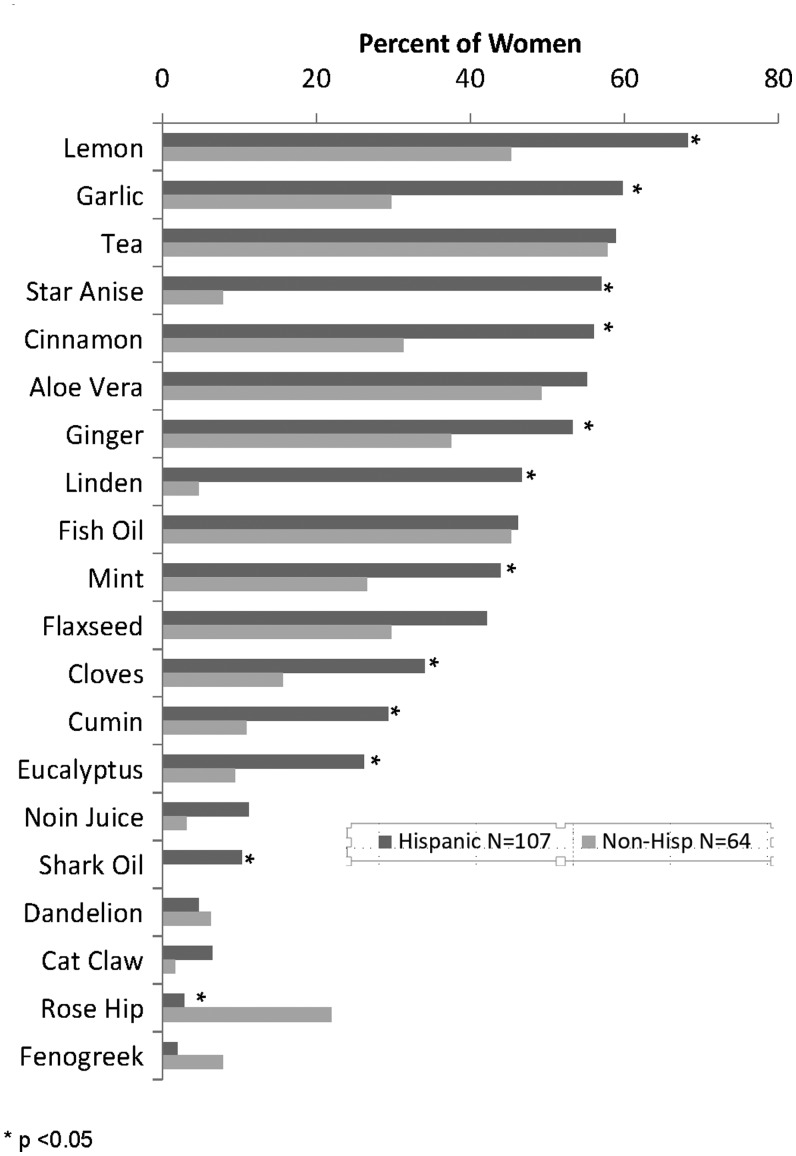

The prevalence of use for items included in the site-specific Herbal remedy questionnaire is shown in Figure 2. Use was very common among women of either race/ethnic group, with 88.8% of Hispanic and 81.3% of non-Hispanic white women reporting the use of at least one herbal remedy. Women reported the use of multiple herbal modalities, with Hispanic women reporting a mean of 7.1 types (±0.47 standard error of the mean [SEM]) and non-Hispanic women reporting 4.4 types (±0.51 SEM; p = 0.0003).

FIG. 2.

Frequency of herbal remedy use for Hispanic and non-Hispanic women at Study of Women's Health Across the Nation, New Jersey site, 2011–2013. Botanical names (in order listed above): Citrus limonium, Allium sativum, Tea (general term applies), Pimphella anisum, Cinnamonum cassia, Aloe barbadensis, Zingiber officinale, Tilia, Mentha, Linum usitatissium, Syzgium aromaticum, Cuminum cyminum, Eucalyptus globulus, Movinda citvifolia, Taraxacum, Uncaria tomentosa, Rosa canina, Trigonella foenum-graecum. The two non-botanicals in the list are fish oil and shark oil.

Table 2 shows the mean number of herbal remedies according to demographic characteristics and number of prescription medications. The number of remedies is significantly greater among women who indicated financial strain and among those without health insurance (p < 0.05). The mean number of remedies used was similar regardless of the number of prescription medications used, with an average of 6.5, 6.3, 5.9, and 5.8 herbal remedies for women taking 0, 1–2, 3–4, or 5 or more prescription medications, respectively (p = 0.91).

Table 2.

Mean Number of Herbal Remedies by Demographic Characteristics and Prescription Drug Use

| Mean N herbal remedies (SE) | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Hispanic | 7.1 (0.5) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 4.4 (0.5) | 0.0003 |

| Education | ||

| ≤High school | 6.8 (0.6) | |

| >High school | 5.6 (0.5) | 0.12 |

| Financial strain | ||

| Somewhat/very hard to pay for basics | 7.0 (0.5) | |

| Not hard at all to pay for basics | 4.9 (0.5) | 0.005 |

| Health insurance | ||

| No | 7.8 (0.8) | |

| Yes | 5.7 (0.4) | 0.02 |

| Number of prescription medications | ||

| 0 | 6.5 (0.9) | |

| 1–2 | 6.3 (0.6) | |

| 3–4 | 5.9 (0.7) | |

| ≥5 | 5.8 (0.8) | 0.91 |

SE, standard error.

Women's attitudes regarding herbal remedies are presented in Table 3. Hispanic women were less likely than non-Hispanic white women to consider herbal remedies to be drugs (15.9% vs. 37.5%; p = 0.005). However, there was no significant difference in the proportions of Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women who felt that herbal remedies are safer then prescription drugs. Hispanic women were more likely to have had herbal remedies recommended by a family member (46.2% Hispanic vs. 28.6% non-Hispanic white; p = 0.02). Hispanic women were also more likely to indicate that they have given an herbal remedy to children or grandchildren, although the trend was not statistically significant. Hispanic women were less likely to indicate that they share the use of herbal remedies with their doctor (14.0% vs. 34.4%; p = 0.001).

Table 3.

Attitudes Regarding Herbal Remedies and Communication with Physicians Regarding Their Use

| Hispanic | Non-Hispanic | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes | |||

| Herbal remedies are drugs | |||

| Yes | 15.9 | 37.5 | 0.005 |

| No | 57.9 | 46.9 | |

| Don't know | 26.2 | 15.6 | |

| Herbal remedies are safer than prescription or over-the-counter drugs | |||

| Yes | 28.0 | 20.3 | 0.45 |

| No | 38.3 | 46.9 | |

| Don't know | 33.6 | 32.8 | |

| A family member has recommended an herbal remedy for me | |||

| Yes | 46.2 | 28.6 | 0.02 |

| No | 53.8 | 71.4 | |

| I have given children/grandchildren herbal remedies | |||

| Yes | 33.6 | 20.6 | 0.07 |

| No | 66.4 | 79.4 | |

| Communication with MD | |||

| My doctor asks me whether I use herbal remedies (%) | |||

| Yes | 37.4 | 28.1 | 0.45 |

| No | 60.7 | 70.3 | |

| Don't know | 1.9 | 1.6 | |

| My doctor has recommended herbal remedies for me (%) | |||

| Yes | 10.3 | 18.8 | 0.12 |

| No | 89.7 | 79.7 | |

| Don't know | 0 | 1.5 | |

| Do you share use of herbal remedies with your doctor? (%) | |||

| Yes | 14.0 | 34.4 | 0.001 |

| No | 85.0 | 32.8 | |

| Don't know | 1.0 | 32.8 | |

MD, medical doctor.

Discussion

We observed a high rate of botanical/herbal usage for both Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women in the SWAN New Jersey cohort. This finding was unexpected as prior studies have suggested that herbal remedies are used more among Hispanics.18,19 The high use among non-Hispanic white women was particularly surprising given that the herbal remedy use questionnaire was designed to include products used within the Hispanic population. The women in the cohort reside in Hudson County, New Jersey, which is ethnically diverse; many of the herbs/botanicals are available in major supermarkets and local grocery stores promoting cross-cultural exposure and accessibility.

The high prevalence of overall CAM use by SWAN participants at the New Jersey site may be the result of aggressive marketing of herbals and botanicals as all-natural products and the ease of purchase without a prescription.20 Alternatively, the expense of prescription medications may be prohibitive for individuals with limited or no health insurance21 and thereby drives the use of botanicals and herbal remedies as an affordable alternative. This may be particularly relevant for the populations queried in this study. Indeed, in our cohort, we observed greater utilization of CAM in women who lacked health insurance or who reported financial strain. Financially strapped women may rely on alternative therapies in lieu of paying for expensive medical prescriptions. When compared with all SWAN sites, over half of the women at the New Jersey site (51.3%) reported that it is very or somewhat hard to pay for basics, whereas the proportions at other SWAN sites ranged from 15.6% to 40.8%. It is important to note that the overall use of CAM in our cohort was greater than those reported in the National Health Interview Survey 2012–20151 (>80% vs. 34% of U.S. adults). Higher financial strain in both Hispanic and non-Hispanic women in our sample may explain why we observed an overall increased use of herbal therapies regardless of race/ethnicity.

Prior work demonstrates that within Hispanic communities, herbal remedies are often purchased from a local Latino/Hispanic market or Botanica or are obtained from individuals' home country or from relatives or friends. Obtaining supplements and treatments in this way may prove far less expensive than obtaining supplements from more traditional stores such as pharmacies and vitamin shops and may also explain herbal polypharmacy by Hispanic women.22

Analyses of the core SWAN CORE CAM questionnaire revealed that regardless of race and ethnicity, prayer, women's vitamin supplements, and herbal tea were the most frequently reported modalities used. The prevalence of prayer and soy supplement use was higher in Hispanic women, while non-Hispanic white women were more likely to report the use of women's vitamin supplements. Few women of either race/ethnic group reported the use of self-help modalities or yoga. This may reflect the low socioeconomic status in our population as yoga and other self-help modalities are often not covered by medical insurance and therefore the expense may be prohibitive. Additionally, cultural attitudes and spiritual beliefs toward Yoga and other self-help modalities may result in lower use by some racial/ethnic groups.1 The SWAN core questionnaire included few queries about specific herbals. The high prevalence of herbal use identified using our more in-depth herbal remedy questionnaire underscores the importance of adding botanicals/herbals to standard CAM questionnaires.

Our data suggest that attitudes toward the use of herbal remedies differ significantly among Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women. Hispanic women in our sample were more likely to say that herbal remedies were recommended by a family member and to indicate that they give herbal remedies to children or grandchildren. This is consistent with data showing that in some Hispanic/Latino populations, attitudes and beliefs about the use of botanical medicines are part of a cultural belief system transmitted through female relatives. Herbal/botanical remedies may have been passed down through generations and may hold a unique importance as a link to countries of origin and culture.7,23

In our sample, Hispanic women were less likely to consider herbal remedies to be drugs. This is consistent with prior studies showing that Hispanics may not consider herbals remedies as therapies, even when specifically taken to treat a minor illness. Instead, they think of them as naturally occurring remedies and part of common curative health practices in their countries of origin.24 Furthermore, Hispanics may believe that these remedies are culturally syntonic and efficacious even when there is no scientific evidence based on Western medical practice standards.11

Importantly, we also found that the majority of women indicated that they do not discuss the use of herbal remedies with their doctor and Hispanic women were only half as likely to do so compared with non-Hispanic white women (14% Hispanics vs. 34% non-Hispanic whites). Hispanic women may also not disclose the use of herbal remedies to Western physicians because they perceive that there is a stigma attached to the use of these treatments.25 Herbal remedies can interfere with the effectiveness and toxicity of prescription drugs; therefore, it is critical that clinical providers appreciate these attitudes within Hispanic populations. The data also indicate that even among non-Hispanic white women, rates of disclosure are low.

It is also important to note that among all women, the use of herbal remedies was high regardless of how many prescription medications were being taken. We observed that the average number of herbal remedies was close to six, regardless of how many prescription medications were used. In a recent American Association of Retired Persons/National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine survey, almost two-thirds (63%) of those surveyed reported simultaneous CAM and prescription drug use.26 This combined with the fact that the majority of women did not disclose the use of herbal therapies suggests the need for increased awareness by clinicians, particularly those who treat Hispanic women, regarding the need to ascertain CAM use and specifically herbal remedies. Further work is needed to determine the extent to which women use CAM instead of prescribed medications or in combination with prescriptions where adverse drug interactions might occur.

A limitation of our study is that our sample was relatively small, and the data are subject to the limitations of self-report. Furthermore, the Hispanic subgroup in our analysis includes a nonhomogeneous Hispanic population, with women of Puerto Rican, Cuban, Dominican, and Central and South American origin. We did not have an adequate sample size to explore differences among these cultural groups.

In conclusion, we observed high rates of CAM use and particularly the use of herbal remedies in our midlife cohort of women. Women in the cohort reported a form of polypharmacy with herbal therapies regardless of the number of prescription medications used, and Hispanic women were less likely to report their use to physicians. Further work is needed to increase physician awareness of the types of alternative therapies used by women in general and by women from different cultural backgrounds. In addition, future studies are needed to assess whether CAM use is related to compliance with traditional treatments and to explore potential interactive effects with pharmaceutical prescriptions.

Acknowledgments

The Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) has grant support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), DHHS, through the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), and the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health (ORWH) (Grant Nos. U01NR004061, U01AG012505, U01AG012535, U01AG012531, U01AG012539, U01AG012546, U01AG012553, U01AG012554, and U01AG012495). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA, NINR, ORWH, or the NIH. The authors acknowledge support from the following institutions: Clinical Centers: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI—Siobán Harlow, PI 2011–present, MaryFran Sowers, PI 1994–2011; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA—Joel Finkelstein, PI 1999–present; Robert Neer, PI 1994–1999; Rush University, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL—Howard Kravitz, PI 2009–present; Lynda Powell, PI 1994–2009; University of California, Davis/Kaiser—Ellen Gold, PI; University of California, Los Angeles, CA—Gail Greendale, PI; Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY—Carol Derby, PI 2011–present, Rachel Wildman, PI 2010–2011; Nanette Santoro, PI 2004–2010; University of Medicine and Dentistry–New Jersey Medical School, Newark, NJ—Gerson Weiss, PI 1994–2004; and the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA—Karen Matthews, PI. NIH Program Office: NIA, Bethesda, MD—Chandra Dutta 2016–present; Winifred Rossi 2012–2016; Sherry Sherman 1994–2012; Marcia Ory 1994–2001; NINR, Bethesda, MD—Program Officers. Central Laboratory: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI—Daniel McConnell (Central Ligand Assay Satellite Services). Coordinating Center: University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA—Maria Mori Brooks, PI 2012–present; Kim Sutton-Tyrrell, PI 2001–2012; New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA—Sonja McKinlay, PI 1995–2001. Steering Committee: Susan Johnson, Current Chair. Chris Gallagher, Former Chair. The authors thank the study staff at each site and all the women who participated in SWAN.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, et al. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. Natl Health Stat Report 2015;79:1–16 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report 2008;12:1–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho DV, Nguyen J, Liu MA, et al. Use of and interests in complementary and alternative medicine by Hispanic patients of a community health center. J Am Board Fam Med 2015;28:175–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mackenzie ER, Taylor L, Bloom BS, et al. Ethnic minority use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM): A national probability survey of CAM utilizers. Altern Ther Health Med 2003;9:50–56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Semin Integr Med 2004;2:54–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amirehsani KA, Wallace DC. Tés, Licuados, and Cápsulas: Herbal self-care remedies of Latino/Hispanic immigrants for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ 2013;39:828–840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ortiz BI, Shields KM, Clauson KA, Clay PG. Complementary and alternative medicine use among Hispanics in the United States. Ann Pharmacother 2007;41:994–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arcury TA, Grzywacz JG, Bell RA, et al. Herbal remedy use as health self-management among older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2007;62:S142–S149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardiner P, Whelan J, White LF, et al. A systematic review of the prevalence of herb usage among racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health 2013;15:817–828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson A, McGrail MR. Disclosure of CAM use to medical practitioners: A review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Complement Ther Med 2004;12:90–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, et al. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med 1993;328:246–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Factor-Litvak P, Cushman LF, Kronenberg F, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among women in New York City: A pilot study. J Altern Complement Med 2001;7:659–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shelley BM, Sussman AL, Williams RL, et al. “They don't ask me so I don't tell them”: Patient-clinician communication about traditional, complementary, and alternative medicine. Ann Fam Med 2009;7:139–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graham RE, Ahn AC, Davis RB, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medical therapies among racial and ethnic minority adults: Results from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey. J Natl Med Assoc 2005;97:535–545 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Planta M, Gundersen B, Petitt JC. Prevalence of the use of herbal products in a low-income population. Fam Med 2000;32:252–257 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sowers MF, Crawford S, Sternfeld B, et al. Design, survey sampling and recruitment methods of SWAN: A multi-center, multi-ethnic, community-based cohort study of women and the menopausal transition. In: Wren J, Lobo RA, Kelsey J, Marcus R, eds. Menopause: Biology and Pathobiology. San Diego: Academic Press, 2000:175–188. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gold EB, Bair Y, Zhang G, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of specific complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use by racial/ethnic group and menopausal status: The Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Menopause 2007;14:612–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tindle HA, Davis RB, Phillips RS, Eisenberg DM. Trends in use of complementary and alternative medicine by US adults: 1997–2002. Altern Ther Health Med 2005;11:42–49 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bair YA, Gold EB, Greendale GA, et al. Ethnic differences in use of complementary and alternative medicine at midlife: Longitudinal results from SWAN participants. Am J Public Health 2002;92:1832–1840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vuckovic N, Nichter M. Changing patterns of pharmaceutical practice in the United States. Soc Sci Med 1997;44:1285–1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaufman DW, Kelly JP, Rosenberg L, et al. Recent patterns of medication use in the ambulatory adult population of the United States: The Slone Survey. JAMA 2002;287:337–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu J, Amirehsani K, Wallace DC, Letvak S. Perceptions of barriers in managing diabetes: Perspectives of Hispanic immigrant patients and family members. Diabetes Educ 2013;39:494–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faurot KR, Filipelli AC, Poole C, Gardiner PM. Patterns of variation in botanical supplement use among Hispanics and Latinos in the United States. Epidemiology 2015;5195 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dole EJ, Rhyne RL, Zeilmann CA, et al. The influence of ethnicity on use of herbal remedies in elderly Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites. J Am Pharm Assoc 2000;40:359–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chao MT, Wade C, Kronenberg F. Disclosure of complementary and alternative medicine to conventional medical providers: Variation by race/ethnicity and type of CAM. J Natl Med Assoc 2008;100:1341–1349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arcury TA, Bell RA, Altizer KP, et al. Attitudes of older adults regarding disclosure of complementary therapy use to physicians. J Appl Gerontol 2013;32:627–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]