Abstract

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) and γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors (GABAARs) are members of the pentameric ligand-gated ion channel superfamily. Drugs acting as positive allosteric modulators of muscle-type α2βγδ nAChRs, of use in treatment of neuromuscular disorders, have been hard to identify. However, identification of nAChR allosteric modulator binding sites has been facilitated by using drugs developed as photoreactive GABAAR modulators. Recently, R-1-methyl-5-allyl-5-(m-trifluoromethyl-diazirinylphenyl) barbituric acid (R-mTFD-MPAB), an anesthetic and GABAAR potentiator, has been shown to inhibit Torpedo α2βγδ nAChRs, binding in the ion channel and to a γ+–α− subunit interface site similar to its GABAAR intersubunit binding site. In contrast, S-1-methyl-5-propyl-5-(m-trifluoromethyl-diazirinylphenyl) barbituric acid (S-mTFD-MPPB) acts as a convulsant and GABAAR inhibitor. Photolabeling studies established that S-mTFD-MPPB binds to the same GABAAR intersubunit binding site as R-mTFD-MPAB, but with negative rather than positive energetic coupling to GABA binding. We now show that S-mTFD-MPPB binds with the same state (agonist) dependence as R-mTFD-MPAB within the nAChR ion channel, but it does not bind to the intersubunit binding site. Rather, S-mTFD-MPPB binds to intrasubunit sites within the α and δ subunits, photolabeling αVal-218 (αM1), δPhe-232 (δM1), δThr-274 (δM2), and δIle-288 (δM3). Propofol, a general anesthetic that binds to GABAAR intersubunit sites, inhibited [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeling of these nAChR intrasubunit binding sites. These results demonstrate that in an nAChR, the subtle difference in structure between S-mTFD-MPPB and R-mTFD-MPAB (chirality; 5-propyl versus 5-allyl) determines selectivity for intra- versus intersubunit sites, in contrast to GABAARs, where this difference affects state dependence of binding to a common site.

Keywords: allosteric regulation, anesthetic, GABA receptor, nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR), photoaffinity labeling

Introduction

Excitatory nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs)2 and inhibitory γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors (GABAARs) are members of the pentameric ligand-gated ion channel superfamily that also contains receptors for the neurotransmitters serotonin and glycine in vertebrates and for glutamate and biogenic amines in invertebrates (1–5). Drugs that modulate nAChR function have many potential therapeutic uses, as nAChR subtypes are widely expressed in neuronal and non-neuronal tissues and are involved in a wide variety of physiological and pathological processes, including neuromuscular disorders, cognition, nicotine addiction, and Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases (6–8). Neuronal nAChR positive allosteric modulators (PAMs), some with subtype selectivity, have been identified through screens of natural products and chemical libraries (9, 10). Muscle-type α2βγδ nAChR PAMs, potentially of use in treatment of ALS, myasthenia gravis, and other neuromuscular disorders, have been harder to identify, and neuronal nAChR PAMs often act as channel blockers of muscle-type nAChRs (11, 12).

Identification of binding sites for allosteric modulators is facilitated by the models of receptor structure that can be derived from crystal structures of soluble, homomeric acetylcholine binding proteins (13, 14) and from X-ray or cryo-electron microscopy structures of distantly related prokaryotic channels and homomeric invertebrate glutamate-gated chloride channels and vertebrate glycine, GABAA, and serotonin receptors (15), as well as a structure of a heteromeric α4β2 neuronal nAChR (16). In an α2βγδ nAChR, agonist-binding sites are in the extracellular domain at the α–γ and α–δ subunit interfaces, and allosteric modulator sites have been identified in proximity to the agonist-binding sites and at corresponding positions at other interfaces (11, 17). The transmembrane domain (TMD) of each receptor subunit consists of a bundle of four transmembrane α helices (M1–M4), with M2 helices from each subunit associating at the central axis of the receptor to form the ion channel and the M1, M3, and M4 helices forming an outer ring in contact with membrane lipids. In addition to drug-binding sites in the TMD within the ion channel, potential intrasubunit drug binding sites are present in pockets within each subunit helix bundle and intersubunit binding sites in pockets at each subunit interface.

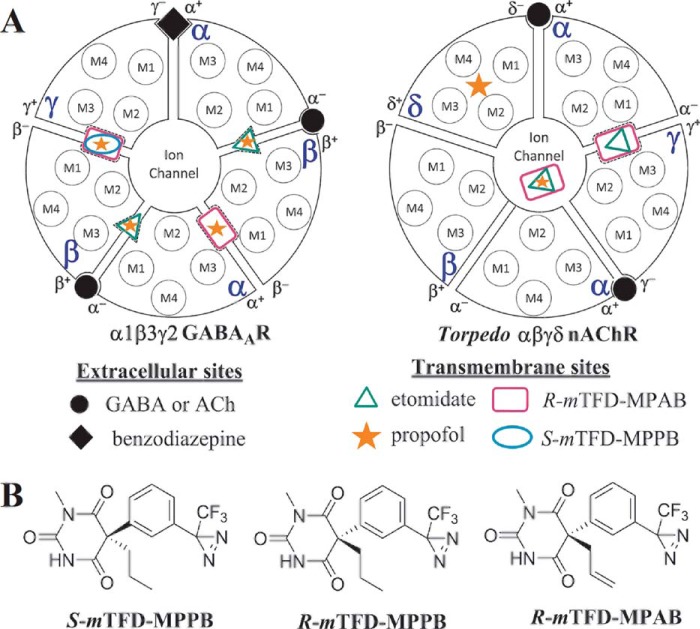

Studies using photoreactive analogs of general anesthetics, including etomidate, propofol, and mephobarbital that act as GABAAR PAMs but as nAChR inhibitors, have identified two homologous classes of intersubunit binding sites in the TMD of α1β3γ2 GABAARs (Fig. 1A; reviewed in Refs. 18 and 19). In α2βγδ nAChRs, these drugs each bind to sites in the ion channel and to intrasubunit sites within the nAChR δ subunit helix bundle and/or intersubunit sites at the γ+–α− subunit interface, where a photoreactive etomidate analog that acts as a low efficacy PAM also binds (20, 21).

Figure 1.

A, locations of drug-binding sites in an α1β3γ2 GABAAR (left) or Torpedo αβγδ nAChR (right). B, chemical structures of S-mTFD-MPPB, R-mTFD-MPPB, and R-mTFD-MPAB.

In α1β3γ2 GABAARs, the photoreactive anesthetic barbiturate R-mTFD-MPAB (Fig. 1B) binds selectively to sites at the α+/γ+–β− interfaces (22, 23). R- and S-mTFD-MPAB act as GABAAR PAMs (22). S-mTFD-MPPB, differing from R-mTFD-MPAB only in terms of chirality and a 5-propyl versus 5-allyl substituent, acts in vivo as a convulsant and as an α1β3γ2 GABAAR inhibitor, whereas R-mTFD-MPPB acts as a PAM (24). Direct GABAAR photolabeling with [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB established that it binds to the same sites as R-mTFD-MPAB, but with opposite state dependence; R-mTFD-MPAB binds with highest affinity in the presence of GABA, whereas S-mTFD-MPPB binds preferentially in the presence of the inverse agonist bicuculline (25).

R- and S-mTFD-MPAB act as potent inhibitors of the Torpedo α2βγδ muscle-type nAChR, each binding with high affinity to a site in the ion channel in the desensitized state and with R-mTFD-MPAB also binding to a site at the γ+–α− interface (26). In this report, we identify the Torpedo nAChR amino acids photolabeled by [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB to determine whether or not it binds to the same sites as R-mTFD-MPAB. We find that both barbiturates bind to the same site in the ion channel. In addition, S-mTFD-MPPB binds in the transmembrane domain to intrasubunit sites within the α and δ subunits, but not to the intersubunit site that binds R-mTFD-MPAB. These results provide the first demonstration of the subtle difference in structure that is sufficient to determine drug selectivity for inter- or intrasubunit sites in a heteromeric nAChR.

Results

Radioligand binding assays

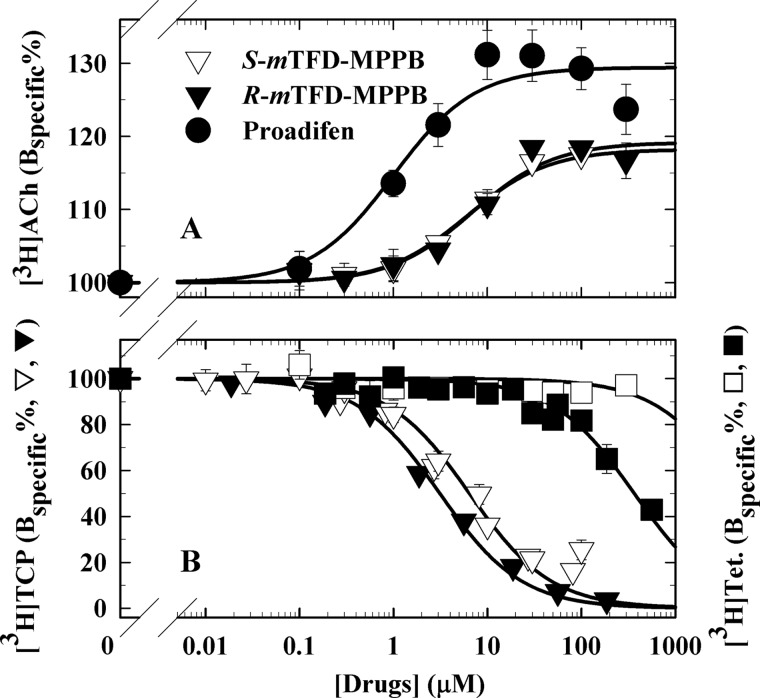

The effect of mTFD-MPPB on the equilibrium binding of [3H]ACh was determined at [3H]ACh concentrations sufficient to occupy ∼20% of nAChR-binding sites to allow determination of enhancement or reduction of binding. Similar to R-mTFD-MPAB (26), S- and R-mTFD-MPPB each increased [3H]ACh binding with EC50 values of 6.4 ± 2.3 and 7.6 ± 2.8 μm, respectively (Fig. 2A and Table 1). The ∼20% maximal enhancement of binding indicated lower efficacy as a desensitizing agent than for proadifen, a prototypic desensitizing non-competitive antagonist (27) that in parallel experiments increased binding by 30% (EC50 = 0.95 ± 0.40 μm).

Figure 2.

Effects of S-mTFD-MPPB (▿, □), R-mTFD-MPPB (▾, ■) or proadifen (●) on the equilibrium binding to Torpedo nAChR-rich membranes of [3H]ACh (A) and [3H]TCP (+ Carb) and [3H]tetracaine (+ α-bungarotoxin) (B). Binding assays were performed at 4 °C by centrifugation. Each independent experiment was performed in duplicate, and the data were normalized to the specific binding in the absence of competitor. Pooled data (average ± S.D.) are plotted. See Table 1 for the number of independent experiments and the calculated IC50/EC50 values. For all samples, the final ethanol concentration was 1% (v/v), a concentration that reduced [3H]TCP and [3H]tetracaine binding by <10% and enhanced [3H]ACh binding by <10%. The total control/nonspecific binding were as follows: for [3H]ACh, 2,600/60 cpm; for [3H]TCP, 6,200/1,600 cpm; for [3H]tetracaine, 4,300/1,180 cpm.

Table 1.

The potencies of S-mTFD-MPPB, R-mTFD-MPPB, and proadifen as modulators of [3H]ACh, [3H]TCP (+Carb), and [3H]tetracaine (+α-bungarotoxin) equilibrium binding to Torpedo nAChRs

For each independent equilibrium binding assay, binding at each modulator concentration was determined in duplicate, and the specific binding at each concentration was normalized to the total specific binding in the absence of modulator. n, number of independent experiments; ND, not determined.

| Ligands | [3H]ACh |

[3H]TCP |

[3H]Tetracaine |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 | Emax | n | IC50 | n | IC50 | n | |

| μm | % | μm | μm | ||||

| S-mTFD-MPPB | 6.4 ± 2.3 | 118 ± 2 | 4 | 6.6 ± 0.9 | 5 | >1000 | 2 |

| R-mTFD-MPPB | 7.6 ± 2.8 | 119 ± 1 | 2 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 2 | 408 ± 27 | 2 |

| Proadifen | 0.95 ± 0.40 | 130 ± 6 | 4 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

We also characterized the effects of S- and R-mTFD-MPPB on the binding of cationic channel blockers that bind preferentially to the nAChR ion channel in the desensitized state stabilized by the agonist Carb ([3H]tenocyclidine ([3H]TCP), a PCP analog (28, 29)) or in the resting, closed channel state stabilized by α-bungarotoxin ([3H]tetracaine (30, 31)). As shown in Fig. 2B and Table 1, in the presence of Carb, S- and R-mTFD-MPPB each fully inhibited [3H]TCP binding with IC50 values of 6.6 ± 0.9 and 3.1 ± 0.3 μm, respectively. In contrast, in the presence of α-bungarotoxin, R-mTFD-MPPB inhibited [3H]tetracaine binding with an IC50 of 408 ± 27 μm, whereas S-mTFD-MPPB even at 300 μm did not inhibit binding (Fig. 2B and Table 1). These results establish that S- and R-mTFD-MPPB each bind in the ion channel with >100-fold higher affinity in the nAChR-desensitized state than in the resting, closed channel state.

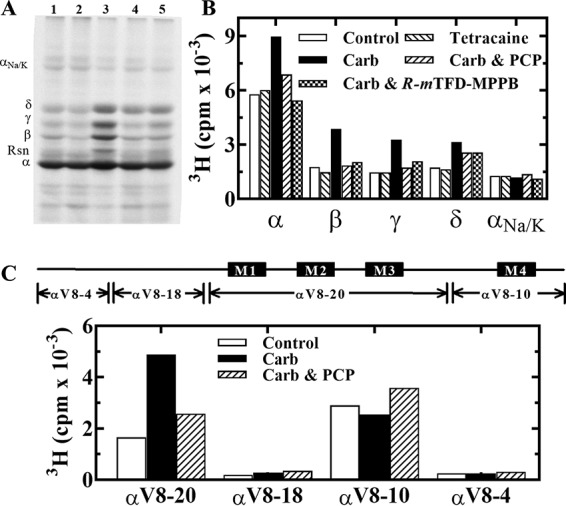

[3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeling of Torpedo nAChR-rich membranes

After irradiation, membrane suspensions were fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and the covalent incorporation of [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB was characterized by fluorography (Fig. 3A) and by liquid scintillation counting of bands excised from the stained gels (Fig. 3B). In the absence of other drugs (control conditions), the nAChR α subunit was labeled most prominently. Photoincorporation into each nAChR subunit was enhanced in the presence of agonist (Carb) compared with control. Tetracaine did not reduce subunit photolabeling in the absence of agonist, but the enhanced nAChR subunit photolabeling in the presence of Carb was reduced in the presence of PCP or R-mTFD-MPPB. For the nAChR α, β, and γ subunits, PCP or R-mTFD-MPPB reduced photolabeling to levels close to that in the control condition, whereas for the δ subunit, the inhibition was partial. These results suggest that the Carb-enhanced nAChR subunit photolabeling results from [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeling in the ion channel in the nAChR-desensitized state, with an additional PCP-insensitive binding site within the nAChR δ subunit.

Figure 3.

[3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photoincorporation into Torpedo nAChR-rich membranes. [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB (0.9 μm) was photoincorporated in the absence (control, lane 1) or presence of 100 μm tetracaine (lane 2), 1 mm Carb (lane 3), 1 mm Carb and 100 μm PCP (lane 4), or 1 mm Carb and 60 μm R-mTFD-MPPB (lane 5), and aliquots in duplicate were fractionated by SDS-PAGE. After staining the gel with GelCodeTM Blue Safe Protein Stain, one set was prepared for fluorography (A), and gel bands were excised from the second for 3H determination (B). The electrophoretic mobilities of the nAChR α, β, γ, and δ subunits, rapsyn (Rsn), and the Na+/K+-ATPase α subunit (αNa/K) are indicated on the left of A. C, 3H incorporation in the large nAChR α subunit fragments generated by in-gel digestion of α subunits with V8 protease. Gel bands containing α subunits were isolated by SDS-PAGE from nAChR-rich membranes photolabeled with 1.5 μm [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB in the absence (control) or presence of 1 mm Carb, without or with 100 μm PCP (Carb and Carb/PCP, respectively). The gel bands containing αV8-20, αV8-18, αV8-10, and αV8-4 were excised from the stained mapping gels, and 3H incorporation was determined by liquid scintillation counting.

To provide an initial characterization of the location of photolabeled residues within a nAChR subunit, we used in-gel digestion of labeled α subunits to generate four large non-overlapping fragments of 4 kDa (αV8-4, predominately starting from αSer-1), 18 kDa (αV8-18, beginning at αThr-52 and containing ACh-binding site segments A and B), 20 kDa (αV8-20, beginning at αSer-173 and containing ACh-binding site segment C and extending through the M1-M2-M3 transmembrane helices), and 10 kDa (αV8-10, beginning at αAsn-339 in the cytoplasmic domain and extending through the M4 helix) (32). Based on liquid scintillation counting, >95% of [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeling was within αV8-20 and αV8-10, with the Carb-enhanced and PCP-inhibitable photolabeling restricted to αV8-20 (Fig. 3C). [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB incorporation within αV8-10 varied by <25% in the three conditions. This demonstrates that S-mTFD-MPPB incorporates primarily within the nAChR TMD rather than the extracellular domain, with agonist-enhanced labeling restricted to the fragment containing the M1, M2, and M3 helices.

[3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabels residues in αM2 and αM1

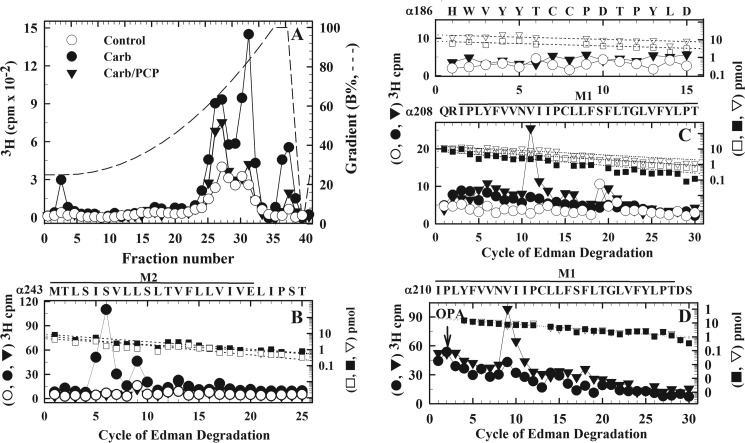

To identify photolabeled amino acids within αV8-20, this fragment was isolated from nAChRs photolabeled on a preparative scale in three conditions (control, Carb, and Carb/PCP). When EndoLys-C digests of αV8-20 were fractionated by rpHPLC (Fig. 4A), there were peaks of 3H eluting at ∼60 and ∼80% organic solvent, where fragments beginning at αHis-186 and extending though αM1 and at αMet-243, the N terminus of αM2, respectively, are known to elute (33). 3H within both peaks was increased in the presence of agonist, but PCP strongly reduced labeling only in the more hydrophobic peak.

Figure 4.

Identification of [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeled amino acids within αM1 and αM2. nAChR-rich membranes were photolabeled with 0.4 μm [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB in the absence of other drugs (control; ○, □), or in the presence of 1 mm Carb (●, ■) or 1 mm Carb and 100 μm PCP (▾, ▿), and αV8–20 was isolated by in-gel digestion of α subunits with V8 protease. A, 3H elution profiles for EndoLys-C digests of αV8–20 fractionated by rpHPLC. B and C, 3H (control (○), Carb (●), and Carb/PCP (▾)) and PTH-derivatives (control (□), Carb (■), and Carb/PCP (▿)) released during sequence analysis of fragments containing αM2 (B) and αM1 (C) from rpHPLC fractions 30–32 and 25–28, respectively. B, when sequencing the fragment beginning at αMet-243 (I0 = 5 (□), 9 (■), and 7 (▿) pmol), the major peak of 3H release in cycle 6 indicates photolabeling in the presence Carb of αSer-248 (αM2-6′), with lower-level labeling of αM2-5′, -9′, -13′, and -17′. For this sample, the efficiencies of photolabeling of αSer-248 were 51 cpm/pmol (Carb), 3 cpm/pmol (control), and 1.8 cpm/pmol (Carb/PCP). C, top, no peaks of 3H release were detected when the fragment beginning at αHis-186 (I0 = 8 (□) and 19 (▿) pmol) was sequenced for 15 cycles. The sequencing filters were then treated with CNBr to cleave at αMet-207. C, bottom, when sequencing was continued from αGln-208 (I0 = 10 (□), 7 (■), and 16 (▿) pmol), the peak of 3H release in cycle 11 was consistent with photolabeling of αVal-218 at efficiencies of <0.2 cpm/pmol (control), 1.6 cpm/pmol (Carb), and 5 cpm/pmol (Carb/PCP). D, 3H (Carb (●) and Carb/PCP (▾)) and PTH-derivatives (Carb (■) and Carb/PCP (▿)) released during sequence analysis of a fragment beginning at αIle-210 (I0 = 22 pmol, both conditions) isolated by rpHPLC from trypsin digests of α subunits from an independent photolabeling of nAChR-rich membranes with 0.4 μm [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB in the presence of 1 mm Carb without or with 100 μm PCP. Sequencing filters were treated with OPA at cycle 2 to prevent further sequencing of any fragments not containing a proline in that cycle. The peak of 3H release in cycle 9 confirmed photolabeling of αVal-218 at efficiencies of 3 cpm/pmol (Carb) and 12 cpm/pmol (Carb/PCP).

For nAChRs labeled in the presence of Carb, sequence analysis of the fragment beginning at αMet-243 revealed a major peak of 3H release in cycles 5 and 6 with additional peaks in cycles 9 and 13, consistent with photolabeling of αIle-247, αSer-248, αLeu-251, and αVal-255 at positions M2–5′, M2–6′, M2–9′, and M2–13′ that line the lumen of the ion channel (Fig. 4B). The efficiencies of photolabeling (cpm/pmol) at M2-5′ and -6′ were 10-fold higher in the presence of Carb than in its absence, and PCP inhibited that photolabeling by >90%, whereas both the state dependence and PCP sensitivity were reduced at M2–9′ (Table 2).

Table 2.

[3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photoincorporation efficiencies at amino acids within Torpedo nAChR M2 helices that line the ion channel (cpm/pmol of PTH-derivative)

The photolabeling efficiency (cpm/pmol of PTH derivative) for each residue was calculated from the observed 3H release, the initial peptide mass, and repetitive yield as described under “Experimental procedures.” n, the number of samples sequenced. For n = 2, the average efficiencies ± S.D. are tabulated.

| Residues | Photolabeling efficiency |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M2-5′ | M2-6′ | M2-9′ | M2-13′ | M2-/17′ | |

| cpm/pmol | |||||

| α (n = 1) | |||||

| Control | 1 | 3.3 | 16 | 1.4 | <1 |

| Carb | 19 | 51 | 21 | 10 | 13 |

| Carb/PCP | 1.5 | 1.8 | 9 | 18 | 10 |

| β | |||||

| Control (n = 1) | 0.6 | 2 | 6 | 1 | <1 |

| Carb (n = 2) | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 15 ± 1 | 21 ± 11 | 4.5 ± 1.8 | 5.8 ± 2.6 |

| Carb/PCP (n = 2) | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 9 ± 4 | 4.2 ± 0.2 |

| γ (n = 2) | |||||

| Control | <1 | 4 ± 1 | 4 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 |

| Carb | 2 ± 1 | 34 ± 6 | 20 ± 13 | 4 ± 1 | 6 ± 2 |

| Carb/PCP | 5 ± 4 | 5 ± 4 | 10 ± 5 | 5 ± 3 | 5 ± 3 |

| δ (n = 2) | |||||

| Control | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 0.20 ± 0.05 | 0.21 ± 0.03 |

| Carb | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 27 ± 2 | 5.2 ± 0.5 | 4.1 ± 0.6 |

| Carb/PCP | <0.1 | 0.30 ± 0.05 | 9.3 ± 1.0 | 5.6 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.1 |

Sequence analysis of the fragment beginning at αHis-186 from nAChRs photolabeled in the absence of agonist revealed no peaks of 3H release during 15 cycles of Edman degradation, which included the core aromatics αTyr-190 and αTyr-198 of ACh binding site segment C (top panel in Fig. 4C). To identify labeling within αM1, the filter was then treated with CNBr to cleave at αMet-207 before M1. Sequencing through αM1 then identified a single peak of 3H release in cycle 11, consistent with photolabeling of αVal-218, but only for the sample from nAChRs photolabeled in the presence of Carb and PCP (bottom panel in Fig. 4C and Table 3).

Table 3.

Pharmacological specificity of [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeling of Torpedo nAChR amino acids within intrasubunit binding pockets in the α and δ subunit helix bundle pockets (cpm/pmol of PTH-derivative)

The photolabeling efficiency (cpm/pmol of PTH derivative) for each residue was calculated from the observed 3H release, the initial peptide mass, and repetitive yield as described under “Experimental procedures.” For Experiment 1, single samples were sequenced to determine photolabeling efficiency in the absence of Carb (EControl), and two independent experiments were carried out in the presence of Carb to determine photolabeling efficiencies in the absence (ECarb) and presence of PCP (ECarb/PCP). To take into account the differences in ECarb between experiments, the effect of PCP was quantified as the ratio ECarb/PCP/ECarb for each paired experiment. For Experiment 2, two αM1 and δM2 samples and single samples for the δ subunit fragments were sequenced. The effect of propofol was quantified as the ratio ECarb/PCP/propofol/ECarb/PCP for each sample. Averages ± S.D. were tabulated when two samples were sequenced.

| Labeled residues | Experiment 1 |

Experiment 2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EControl | ECarb | Ratio ECarb/PCP/ECarb | ECarb/PCP | Ratio ECarb/PCP/propofol/ECarb/PCP | |

| cpm/pmol | cpm/pmol | cpm/pmol | |||

| αVal-218 | <0.6 | 2.4 ± 1.1 (n = 2) | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.2 (n = 2) | 0.3 ± 0.2 |

| δPhe-232 | <0.2 | 5.3 ± 1.2 (n = 2) | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 2 | 0.4 |

| δThr-274 | 0.2 ± 0.2 (n = 2) | 4.5 ± 1.8 (n = 3) | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.6 (n = 2) | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| δIle-288 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.8 | 0.25 | 0.6 |

To confirm [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeling of αVal-218 in αM1, fragments beginning at αIle-210 were isolated for sequence analysis by rpHPLC from trypsin digests of α subunit (26) from an independent photolabeling experiment in the presence of Carb or Carb plus PCP (Fig. 4D). The peak of 3H release in cycle 9 confirmed photolabeling of αVal-218 at ∼3-fold higher efficiency in the presence of Carb and PCP than in the presence of Carb alone (Table 3). There was no evidence of photolabeling of αLeu-231, the residue in αM1 at the γ+–α− interface photolabeled by [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB (26). In Torpedo nAChR structural models based either upon cryo-electron microscopy analyses of Torpedo nAChR-rich membrane tubular crystals (34) or X-ray structure of expressed, purified (α4)2(β2)3 human nAChR (16), αVal-218 projects into the α subunit helix bundle pocket (see “Discussion”).

[3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabels δ subunit residues in the ion channel and in the helix bundle pocket

That PCP produced only a partial inhibition of the Carb-enhanced labeling in the δ subunit (Fig. 3B) indicated that [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB may photolabel nAChR δ subunit residues in addition to those in the ion channel. The δ subunit helix bundle pocket is a likely site, because the photoreactive propofol analog [3H]AziPm binds there in an agonist-dependent manner, photolabeling residues in δM1 (δPhe-232) and δM2 (δThr-274 and δM2–18′), with photolabeling inhibited by propofol but not by PCP (35).

Photolabeling within δM1 and δM2 was determined by sequence analysis of fragments of ∼13 kDa that can be isolated by SDS-PAGE and rpHPLC from δ subunit digested with EndoLys-C (35, 36). When these fragments from [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB-labeled δ subunits were separated by rpHPLC (Fig. 5A), the major peak of 3H eluted at ∼70% organic solvent, where the fragment beginning at the N terminus of δM2 (δMet-257) elutes, and a minor peak of 3H eluted at ∼60% organic where the fragment beginning at δPhe-206 before δM1 elutes. Sequence analysis of the fragment beginning at δMet-257 (Fig. 5B) showed that for nAChRs labeled in the presence of Carb, there was a major peak of 3H release in cycle 9 with smaller peaks of release in cycles 6, 13, 17, and 18, indicating primary photolabeling at δM2-9′ in the ion channel with lower level photolabeling of channel lining residues at δM2–6′, 13′, and 17′ as well as labeling of δM2–18′ (δThr-274) that contributes to the δ subunit helix bundle. Photolabeling of M2-6′ and M2-9′ was at 5–10-fold higher efficiency in the desensitized state (Carb) than in the absence of agonist, whereas PCP in the presence of Carb inhibited photolabeling at M2-6′ and M2-9′ by ∼90 and ∼70%, respectively, with little, if any, inhibition of photolabeling at M2-13′ and M2-18′ (Tables 2 and 3).

Figure 5.

Identification of [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeled amino acids within δM1 and δM2. EndoLys-C digests of δ subunits from the photolabeling experiment of Fig. 4 were fractionated by Tricine SDS-PAGE. A, 3H (control (○), Carb (●), and Carb/PCP (▾)) elution profile when material from an ∼13-kDa gel band was further fractionated by rpHPLC. B and C, 3H (Control (○), Carb (●), and Carb/PCP (▾)) and PTH-derivatives (control (□), Carb (■), and Carb/PCP (▿)) released during sequence analysis of fragments containing δM2 (B) and δM1 (C) from rpHPLC fractions 27–29 and 23–25, respectively. B, when sequencing the fragment beginning at δMet-257 (I0 = 90 pmol, each condition), the major peak of 3H release in cycle 9 indicated photolabeling in the presence of Carb of δLeu-265 (δM2-9′), with lower level labeling of δM2-6′, -13′, -17′, and -18′. The efficiencies of δLeu-265 photolabeling were 26 cpm/pmol (Carb), 3 cpm/pmol (control), and 10 cpm/pmol (Carb/PCP). C, when sequencing the fragment beginning at δPhe-206 (I0 = 32 pmol, each condition), the peak of 3H release at cycle 27 indicated photolabeling of δPhe-232 at efficiencies of <0.2 cpm/pmol (control), 6 cpm/pmol (Carb), and 10 cpm/pmol (Carb/PCP). The small peak of 3H release at cycle 9 (Carb) is consistent with photolabeling of δM2-9′ in the fragment beginning at δMet-257, which was present at ∼5% the level of the δPhe-206 fragment.

Sequence analysis of the fragment beginning at δPhe-206 (Fig. 5C) revealed a single major peak of 3H release at cycle 27, consistent with photolabeling of δPhe-232 in δM1, for the sample from nAChRs labeled in the presence of agonist. That residue was photolabeled at >10-fold higher efficiency in the presence of Carb than in its absence, and PCP in the presence of Carb slightly enhanced rather than inhibited photolabeling (Table 3).

Propofol inhibits intrasubunit binding site photolabeling

Propofol, a widely used intravenous anesthetic and GABAAR PAM, binds to intersubunit binding sites in GABAARs (37). In Torpedo nAChRs, propofol acts as a desensitizing negative allosteric modulator and, based upon inhibition of [3H]AziPm photolabeling, it binds in the δ subunit helix bundle pocket and also within the ion channel (35). To determine whether propofol also bound in the α subunit helix bundle pocket, we examined the effects of propofol on [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeling in the presence of Carb with PCP included to enhance [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeling αM1 and minimize photolabeling in the ion channel. As shown in Fig. 6A and Table 3, sequence analysis through αM1 established that propofol inhibited photolabeling of αVal-218 in the presence of Carb and PCP. Similarly, sequence analysis of photolabeling in δM1 and δM2 (Fig. 6, B and C) established that propofol also inhibited photolabeling in the δ helix bundle pocket of δPhe-232 and δThr-274 (δM2-18′) (Table 3) as well as in the ion channel (δM2-9′, -13′, and -17′). Consistent with the results of Fig. 5B, no photolabeling of δM2–6′ was seen in the presence of PCP. These results indicate that in Torpedo nAChRs, S-mTFD-MPPB binds to sites within the α and δ subunit helix bundle pockets, and propofol inhibits binding at both sites.

Figure 6.

Propofol inhibits [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeling in αM1 (αVal-218), δM1 (δPhe-232), and δM2. Fragments containing αM1 (A), δM1 (B), and δM2 (C) were isolated for sequence analysis from nAChR-rich membranes photolabeled with 0.4 μm [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB in the presence of 1 mm Carb + 100 μm PCP (▾, ▿) or 1 mm Carb + 100 μm PCP + 100 μm propofol (♦, ♢). Shown are 3H (▾, ♦) and PTH-derivatives (▿, ♢) released during sequence analysis of fragments beginning at αIle-210 (A, I0 = 50 pmol, each condition, sequencing filters treated with OPA at cycle 2), δPhe-206 (B, I0 = 45 pmol, each condition), and δMet-257 (C, I0 = 100 pmol, each condition). The peaks of 3H release in cycles 9 (A) and 27 (B) indicated photolabeling of αVal-218 at 1.7 cpm/pmol (Carb/PCP) and 0.3 cpm/pmol (Carb/PCP/propofol) and of δPhe-232 at 2 cpm/pmol (Carb/PCP) and 0.8 cpm/pmol (Carb/PCP/propofol). C, the peaks of 3H release at cycles 9, 13, 17, and 18 indicated photolabeling of ion channel residues δM2-9′, -13′, and -17′ and of δThr-274 in the δ helix bundle, with propofol inhibiting photolabeling by 60–80%.

[3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeling in βM2 and γM2

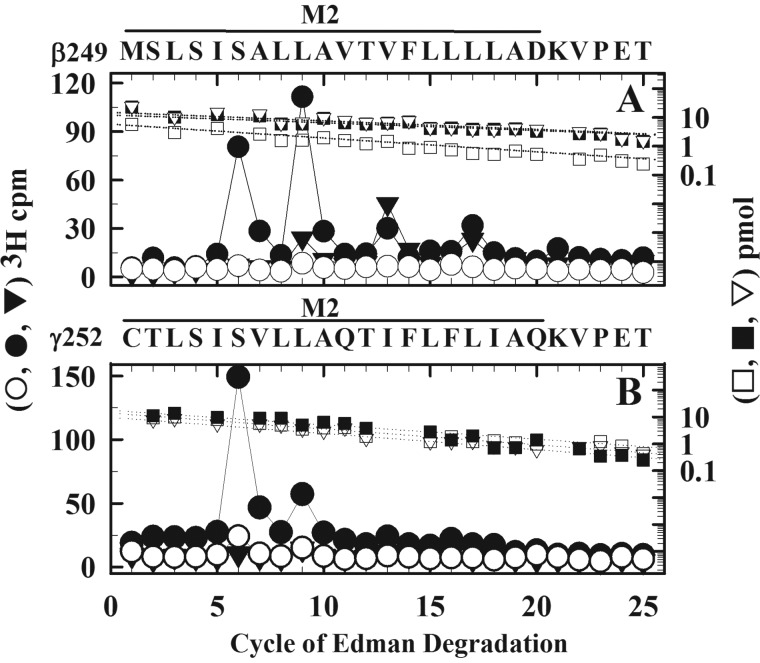

To extend the characterization of photolabeling in the M2 ion channel domain, we also sequenced fragments beginning at the N termini of βM2 and γM2, fragments beginning at βMet-249 that can be isolated from subunit trypsin digests by SDS-PAGE and rpHPLC (38) and at γCys-252 that can be isolated by rpHPLC from EndoLys-C digests of ∼24- or 14-kDa γ subunit fragments produced by in-gel digestion with V8 protease fragment (26, 39). Sequencing through βM2 from nAChRs photolabeled in the presence of agonist (Fig. 7A) revealed major peaks of 3H release in cycles 6 and 9, with additional peaks in cycles 13 and 17, consistent with photolabeling ion channel residues M2-6′, -9′, -13′, and -17′ Sequencing through γM2 (Fig. 7B) revealed a major peak of 3H release in cycle 6 with an additional peak in cycle 9. As seen for photolabeling in αM2 and δM2, labeling efficiency at M2-6′ was increased by ∼7-fold in the presence of agonist compared with the absence, and PCP strongly inhibited photolabeling at M2-6′ and -9′, but not at M2-13′ or M2-17′ (Table 2).

Figure 7.

Agonist-enhanced and PCP-inhibitable [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeling within βM2 (A) and γM2 (B) helices. 3H (control (○), Carb (●), and Carb/PCP (▾)) and PTH-derivatives (control (□), Carb (■), and Carb/PCP (▿)) released during sequencing are shown for fragments isolated from β and γ subunits from the photolabeling experiment of Fig. 5. The fragment beginning at βMet-249 was isolated by Tricine SDS-PAGE and rpHPLC from β subunit trypsin digests. The fragment beginning at γCys-252 was isolated by rpHPLC from an EndoLys-C digest of ∼14-kDa fragments produced by in-gel digestion of γ subunit with V8 protease. A, for the fragment beginning at βMet-249 (I0 = 6 (□), 12 (■), and 15 (▿) pmol), the major peaks of 3H release in cycles 6 and 9 (Carb) indicate photolabeling of βM2-6′ (βSer-254) and βM2-9′ (βLeu-257) with lower-level labeling at βM2-13′ and βM2-17′. The efficiencies of photolabeling for control/Carb/Carb + PCP were as follows: for βM2–6′, 2/15/0.6 cpm/pmol; for βM2-9′, 6/28/5 cpm/pmol. B, for the fragment beginning at γCys-252 (I0 = 14 (□), 17 (■), and 10 (▿) pmol), the peak of 3H release at cycle 6 in B indicates photolabeling of γM2-6′ (γSer-257) at 4.7 cpm/pmol (control), 29 cpm/pmol (Carb), and 1.4 cpm/pmol (Carb/PCP).

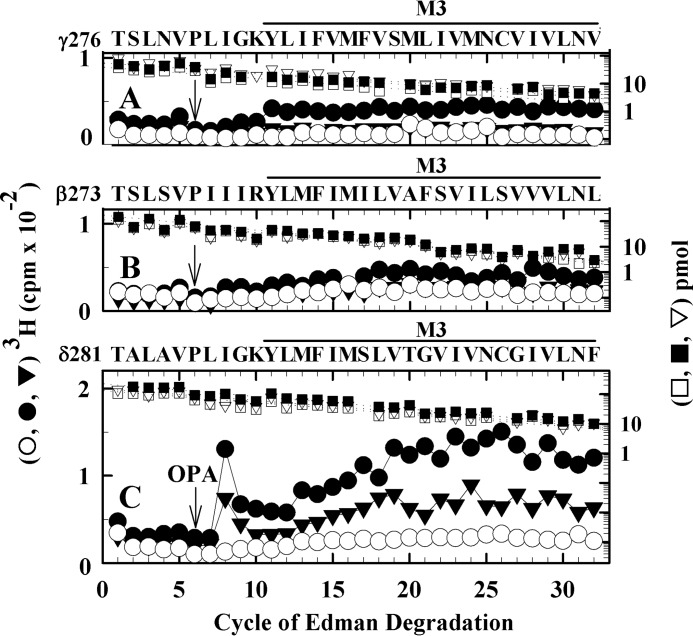

Photolabeling in the M3 helices

Inspection of nAChR structural models allows identification of residues in M3 helices that are predicted to be exposed to lipid, to intersubunit interfaces, or to the intrasubunit helix bundles pocket. [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeled residues in γM3 (γMet-299) and αM1 (αLeu-231) that contribute to a binding pocket at the γ+–α− interface (26). Photolabeling of γMet-299 was state-independent and insensitive to PCP, but it was inhibited in a concentration-dependent manner by R-mTFD-MPAB. In contrast, the hydrophobic probe [125I]TID, which also contains the trifluoromethylphenyl diazirine reactive group, photolabeled γPhe-292, γLeu-296, and γAsn-300, residues exposed at the lipid interface, and the corresponding residues in βM3 and δM3 (40). To determine whether [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeled γMet-299 or other residues in γM3, we isolated and sequenced a fragment beginning at γThr-276 from nAChRs labeled in the absence or presence of Carb or in the presence of Carb and PCP (Fig. 8A). We found no evidence of photolabeling (peaks of 3H release above background) in 30 cycles of Edman degradation. Similarly, there was no evidence of photolabeling in βM3 (Fig. 8B). [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB incorporation in γM3 and βM3, if it occurred, was at <10% the photolabeling efficiency of ion channel residues (Carb). In contrast, [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeled γMet-299 at the same efficiency as the most prominently labeled residues in the ion channel.

Figure 8.

[3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabels δIle-288 without labeling other residues within γM3 (A), βM3 (B), or δM3 (C) helices. 3H (control (○), Carb (●), and Carb/PCP (▾)) and PTH-derivatives (control (□), Carb (■), and Carb/PCP (▿)) released during sequencing are shown for fragments isolated by rpHPLC from V8 protease digests of nAChR β, γ, and δ subunits from the photolabeling experiment of Fig. 5. The major peaks of 3H from the rpHPLC fractionations of the subunit digests were sequenced with OPA treatment at cycle 6 of Edman degradation (indicated by the arrows), which prevents further sequencing of peptides not containing a proline at this cycle and chemically isolates the fragments beginning at γThr-276, βThr-273, and δThr-281. A, after OPA treatment, sequencing continued for the fragment beginning at γThr-276 (I0 = 38 (□) and 55 (■, ▿) pmol). B, after OPA treatment, sequencing continued of the fragment beginning at βThr-273 (I0 = 110 (□, ▿) and 170 (■) pmol). No evidence was seen for labeling in γM3 or βM3, based upon the absence of any peaks of 3H release >25% above the background level of release. C, after OPA treatment, sequencing continued for the fragment beginning at δThr-281 (I0 = 140 (□, ▿) and 220 (■) pmol). The peak of 3H release at cycle 8 in C indicated photolabeling of δIle-288 at <0.2 cpm/pmol (control), 2.0 cpm/pmol (Carb), and 1.5 cpm/pmol (Carb/PCP). The progressive increase in background 3H release in cycles 13–32 of Edman degradation results from random cleavages of other fragments in the sequenced sample that contain residues labeled in δM2 and δM1. Although present, sequencing of those fragments was prevented by treatment of the sequencing filters with OPA in cycle 6, which blocks further sequencing of peptides not containing a proline at that cycle (44, 54).

Sequence analysis of the corresponding fragment from the δ subunit, which begins at δThr-281, revealed a single major peak of 3H release in cycle 8 (δIle-288) for nAChRs labeled in the presence of agonist but not in the absence (Fig. 8C and Table 3). Similar to δPhe-232 in δM1 and δThr-274 in δM2, δIle-288, which is in the M3 helix, contributes to the binding pocket near the extracellular end of the δ subunit helix bundle. All three residues were also photolabeled in an agonist-dependent manner by [125I]TID (41, 42) and by the photoreactive propofol analog [3H]AziPm (35), but not by [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB (26).

[3H]S-mTFD-MPPB labeling in αM4

To further examine photolabeling at the lipid interface, we also sequenced the fragment beginning at αTyr-401, which contains αM4 (Fig. 9). Within αM4, the single major peak of 3H release in cycle 12 indicated photolabeling of αCys-412 at similar efficiency in the absence or presence of Carb or Carb plus PCP. αCys-412 is the residue in αM4 labeled most efficiently by [125I]TID, [3H]AziPm, and [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB (26, 35, 40). Similar to [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB, the efficiency of [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeling of αCys-412 (∼60 cpm/pmol), although state-independent, was similar to that seen for the ion channel residues labeled most efficiently in the nAChR-desensitized state.

Figure 9.

[3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabels αCys-412 in αM4. 3H (control (○), Carb (●), and Carb/PCP (▾)) and PTH-derivatives (control (□), Carb (■), and Carb/PCP (▿)) released during sequencing are shown for the fragment beginning at αTyr-401 ((I0 = 16 (□, ■) and 8 (▿) pmol) isolated by rpHPLC from a trypsin digest of αV8-10 from the photolabeling experiment of Fig. 5. The peak of 3H release at cycle 12 indicates photolabeling of αCys-412 at efficiencies of 50 cpm/pmol (control and Carb) and 70 cpm/pmol (Carb/PCP).

Discussion

S-mTFD-MPPB, a convulsant in vivo, acts as an inhibitor of αβγ GABAARs, whereas R-mTFD-MPAB, which differs only by chirality and the presence of a 5-allyl rather than 5-propyl substituent, acts as an anesthetic in vivo and as an αβγ GABAAR PAM (22, 24). In α1β3γ2 GABAARs, photoaffinity labeling studies established that S-mTFD-MPPB and R-mTFD-MPAB bind to the same binding site in the TMD at the γ+–β− subunit interface, but with the opposite state dependence and in different orientations (23, 25). S-mTFD-MPPB binds preferentially in the presence of bicuculline, an inverse agonist, whereas R-mTFD-MPAB binds preferentially in the presence of GABA. In a muscle-type nAChR, R-mTFD-MPAB acts as an inhibitor, binding to sites in the TMD in the ion channel and at the γ+–α− subunit interface (26).

To determine whether S-mTFD-MPPB and R-mTFD-MPAB also bind to the same binding sites in a nAChR, in this report, we used radioligand binding assays and photoaffinity labeling to identify binding sites in the Torpedo nAChR for S-mTFD-MPPB. We found that S-mTFD-MPPB binds to the same site in the nAChR ion channel in the desensitized state as R-mTFD-MPAB and with similar high affinity. However, our results establish that S-mTFD-MPPB does not bind to the intersubunit site that binds R-mTFD-MPAB. Rather, S-mTFD-MPPB binds to homologous intrasubunit sites in the α and δ subunits in pockets formed by each subunit's bundle of transmembrane helices. Furthermore, propofol, but not the positively charged channel blocker PCP, inhibits binding of S-mTFD-MPPB to those intrasubunit sites. Whereas anesthetics, including halothane, propofol, and the photoreactive propofol analog AziPm, have been shown previously to bind in a state-dependent manner within the δ subunit helix bundle pocket (35, 43), this is the first time, to our knowledge, that anesthetics or other drugs have been found to bind within the α subunit intrasubunit site.

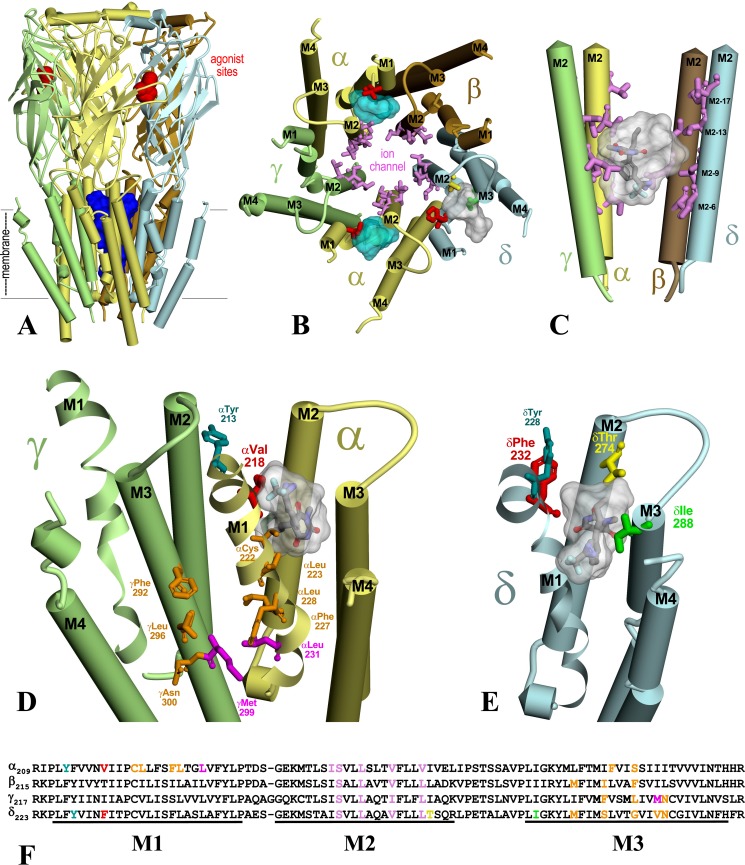

A comparison of S-mTFD-MPPB and R-mTFD-MPAB actions and binding sites in Torpedo nAChR and α1β3γ2 GABAAR is shown in Table 4. The locations of the amino acids photolabeled by [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB that define the ion channel and intrasubunit binding sites are shown in Fig. 10 in a Torpedo californica nAChR homology model based upon the recently determined structure of an expressed human (α4)2(β2)3 nAChR (16). Also shown in Fig. 10 (B–E) are the most energetically favorable binding poses predicted by computational docking for S-mTFD-MPPB in each of the binding sites.

Table 4.

Comparison of interactions of R-mTFD-MPAB and S-mTFD-MPPB with Torpedo α2βγδ nAChR and α1β3γ2 GABAAR

| Drugs |

Torpedo α2βγδ nAChR |

α1β3γ2 GABAAR |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity | Binding sites | State dependence | Activity | Binding sites | State dependence | |

| R-mTFD-MPAB | Inhibitor | Ion channel | Desensitized | Enhancer | Intersubunit (α+–β− and γ+–β−) | Desensitized (+ GABA) |

| Intersubunit (γ+–α−) | No | |||||

| S-mTFD-MPPB | Inhibitor | Ion channel | Desensitized | Inhibitor | Intersubunit (γ+–β−) | Resting (+bicuculline) |

| Intrasubunit (α and δ) | Desensitized | |||||

Figure 10.

S-mTFD-MPPB binding sites in the Torpedo nAChR. A T. californica nAChR homology model was constructed based on the crystal structure of human (α4)2(β2)3 nAChR (Protein Data Bank entry 5KXI (16)). A, side view of the nAChR extracellular and transmembrane domains (α (yellow), β (brown), γ (green), and δ (light blue)) with nicotine (red Connolly surface) in the ACh-binding sites and the ion channel in blue. B, a view of the nAChR TMD from the base of the extracellular domain. C, the binding site in the ion channel. D and E, views from the lipid of the γ–α subunit interface (D) and the δ subunit TMD (E), at a tilt angle optimizing visualization of the α and δ subunit helix bundle pockets. The amino acids photolabeled by [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB are shown in stick representation in the ion channel (B and C; pink), in the α subunit helix bundle (B and D; αVal-218 (red)), and in the δ subunit helix bundle (B and E; δPhe-232 (red), δThr-274 (yellow), and δIle-288 (green)). In C–E, the locations of S-mTFD-MPPB (molecular volume = 269 Å3) docked in the binding sites are shown in stick representations (carbon (gray), hydrogen (white), oxygen (red), nitrogen (blue), and fluorine (cyan)) in the most favorable binding mode and/or as Connolly surface representations of the volumes defined by the ensemble of the 10 most energetically favorable binding poses. Also highlighted in D and E are the amino acids photolabeled by [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB (magenta, αLeu-231 and γMet-299 (26)) at the γ–α interface, by [14C]halothane (teal, αTyr-213 and δTyr-228 (43)) in the helix bundle pockets, and by [125I]TID (orange, αCys-222, αLeu-223, αPhe-227, αLeu-228, γPhe-292, γLeu-296, and γAsn-300) at the lipid interface. F, subunit sequence alignment for the M1–M3 region, with the same color coding of amino acids as shown in B–E to identify photolabeled residues.

S-mTFD-MPPB and propofol bind within the α subunit helix bundle pocket

In models of nAChR based upon the structures of the α4β2 (Fig. 10D) or Torpedo nAChR (not shown), αVal-218 in αM1, which is photolabeled by [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB but not by [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB, projects into the α subunit helix bundle pocket. In the aligned subunit sequences (Fig. 10F), αVal-218 is the amino acid homologous to δPhe-232 in δM1, which is in the δ subunit helix bundle pocket and photolabeled by [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB, [125I]TID, and [3H]AziPm, but not by [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB (26, 35, 38). In the presence of Carb and PCP, αVal-218 was photolabeled by [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB at similar efficiency as δPhe-232 or δThr-274 (δM2-18′), another photolabeled residue projecting into the δ subunit helix bundle pocket (Table 3). Propofol at 100 μm inhibited αVal-218 photolabeling by ∼70%, and it inhibited photolabeling of each δ subunit helix bundle residue by ∼50%. We found no evidence of [3H]S-mTFD-MPAB labeling of αM2-18′ (αIle-260), but our procedures generate αM2 fragments at only 10% the level of δM2 fragments, and thus, labeling of αM2-18′ would not be detectable if labeled at a similar efficiency as δM2-18′.

The efficiency of [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeling of αVal-218 was 3-fold higher in the presence of Carb and PCP than in the presence of Carb alone, whereas PCP inhibited [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeling of the ion channel residues M2-6′ by ∼90% and M2-9′ by 50–80%. The simplest interpretation of the enhanced αVal-218 photolabeling is that when PCP binds in the ion channel at the level of M2-2′ and M2-6′, there is a change in structure of the α subunit helix bundle that increases S-mTFD-MPPB binding affinity. Interestingly, for TDBzl-etomidate, which binds at the γ+–α− interface and photolabels αM2-10′, PCP increased by ∼2-fold αM2-10′ photolabeling in the presence of Carb (44). These results indicate that PCP binding in the ion channel stabilizes an nAChR structure that differs from that of the desensitized state stabilized by agonist alone.

The selective [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB labeling in αM1 of αVal-218 contrasts strongly with the photolabeling of other residues in αM1 reported previously for other drugs. Thus, [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeled αLeu-231, with any photolabeling of αVal-218, if it occurred, at <5% the efficiency of αLeu-231 photolabeling (26). αLeu-231 contributes to a binding pocket in the γ+–α− interface (Fig. 10D), where [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB also photolabels γMet-299 at 10-fold higher efficiency than αLeu-231. [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeling of γMet-299 or other residues in γM3, if it occurs, is at <25% the efficiency of αVal-218. In addition to R-mTFD-MPAB, photoreactive analogs of etomidate also bind to this intersubunit site (44, 45). [14C]Halothane (43) and a buproprion analog ([125I]SADU-3-72 (46)) each photolabel αTyr-213 at the extracellular end of αM1. Although within 9 Å of αVal-218, in current structural models, αTyr-213 projects more toward the γ+–α− interface than into the intrasubunit pocket (Fig. 10D). Early studies with [125I]TID (40) established photolabeling at the lipid interface in γM3 of γPhe-292, γLeu-296, and γAsn-300 and in αM1 of αCys-222, αLeu-223, αPhe-227, and αLeu-228.

S-mTFD-MPPB and propofol bind within the δ subunit helix bundle pocket

As seen for other nAChR negative allosteric modulators, including [14C]halothane (43), [125I]TID (36, 41), and the photoreactive anesthetics ([3H]TFD-etomidate and [3H]AziPm (35, 45)), [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeled in an agonist-dependent manner residues contributing to the δ subunit helix bundle pocket (Fig. 10E). [125I]TID photolabeling was greatly enhanced in the nAChR open channel and transient desensitized states compared with the equilibrium desensitized state (36, 42), and further studies using rapid-mixing and freeze-quench techniques will be necessary to determine whether [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB has a similar state dependence. Propofol inhibition of [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeling of these residues is consistent with its previously reported inhibition of [3H]AziPm photolabeling (35). In contrast to the enhanced [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeling of αVal-218 in the presence of PCP, little, if any, enhancement was seen for photolabeling in the δ subunit helix bundle. That PCP did not enhance δ intrasubunit photolabeling serves as a control that the enhanced photolabeling seen at αVal-218 results from positive allosteric coupling between PCP binding in the channel and the α intrasubunit site and is not simply due to an increase in the free [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB concentration resulting from its displacement by PCP from the ion channel.

S-mTFD-MPPB binding in the nAChR ion channel

Barbiturates of diverse structures act as state-dependent inhibitors of Torpedo nAChR (47), and they probably bind to sites in the ion channel because they fully inhibit binding of channel blockers (48, 49). Our photolabeling results establish that S-mTFD-MPPB binds to the same region in the ion channel as R-mTFD-MPAB (26) and with the same >10-fold selectivity for the desensitized state compared with the resting, closed channel state. Both barbiturates photolabel residues at M2-6′ and M2-9′ most efficiently and also photolabel M2-13′ and M2-17′. Consistent with the location in the agonist-stabilized desensitized state of the high affinity PCP binding site near the cytoplasmic end of the ion channel (50) and the capacity of PCP and uncharged anesthetics to bind simultaneously in the channel, PCP fully inhibited photolabeling at the level of M2-6′ but did not inhibit labeling at the level of M2-13′ or M2-17′. Whereas S-mTFD-MPPB and R-mTFD-MPAB, which are N-methylated, bind in the ion channel preferentially in the desensitized state, many barbiturates lacking the N-methyl group bind preferentially in the resting, closed channel state (49). In recently solved crystal structures of the cationic prokaryotic nAChR homolog GLIC in a locally closed state, the barbiturate binding site in the ion channel has also been localized to the level of M2-2′ to M2-9′ (51).

S-mTFD-MPPB and R-mTFD-MPAB each bind with higher affinity to a site in the ion channel than to intra- or intersubunit sites, and it is binding to the ion channel site that most likely produces nAChR desensitization and inhibition for nAChRs equilibrated with either drug. However, further studies defining the kinetics of inhibition and kinetics of binding to these different classes of sites will be necessary to determine whether either or both barbiturates act primarily as an open channel blocker upon transient exposure to drug and agonist. Electrophysiological and time-resolved photolabeling studies have shown that TID binding to the δ subunit intrasubunit site contributes to inhibition upon initial exposure and that binding in the ion channel occurs more slowly (36).

Computational docking calculations

Based upon calculated CDOCKER interaction energies, S-mTFD-MPPB is predicted to bind to the α (−49 kcal/mol) and δ (−40 kcal/mol) subunit intrasubunit sites and with lower affinity in the ion channel (−37 kcal/mol at the cytoplasmic end centered near M2-2′, −28 kcal/mol at the level of M2-6′ and -9′). However, the results of these calculations also predict that R-mTFD-MPAB binds with similar affinity as S-mTFD-MPPB to the intrasubunit sites that it does not photolabel and that S-mTFD-MPPB binds with similar affinity as R-mTFD-MPAB (−30 kcal/mol) to the γ+–α− site that it does not photolabel. Potentially, the use of improved lipid-embedded nAChR structural models and docking algorithms in conjunction with molecular dynamics simulations may facilitate computational predictions consistent with the experimental evidence that S-mTFD-MPPB binds to intrasubunit sites, whereas R-mTFD-MPAB binds to an intersubunit site.

Functional significance of intrasubunit and intersubunit binding sites in muscle-type nAChR

There is great interest in developing PAMs for muscle-type nAChRs that could be of use in the treatment of ALS, myasthenia gravis, and other neuromuscular disorders. However, this has proven challenging, as most general anesthetics that act as GABAAR PAMs (21) and many neuronal nAChR PAMs act as potent α2βγδ nAChR channel blockers (11, 12). For Torpedo nAChRs, studies with photoreactive anesthetics led to the identification of drugs that bind with only low affinity to the ion channel, including TDBzl-etomidate, a low efficacy PAM that binds to the γ+–α− intersubunit site (44) and TFD-etomidate, a potent inhibitor that binds to that intersubunit site and to the δ subunit helix bundle pocket (45). The identification of S-mTFD-MPPB as a drug binding to the α subunit intrasubunit pocket will facilitate the identification of other drugs binding potentially with higher affinity and selectivity to that site.

Experimental procedures

Materials

Torpedo nAChR-rich membranes, isolated from T. californica electric organs (Aquatic Research Consultants, San Pedro, CA) as described (52), contained ∼1 nmol of [3H]ACh binding sites/mg of protein, as determined by an ultracentifugation assay. R- and S-mTFD-MPPB, R-mTFD-MPAB, and [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB (49.9 Ci/mmol) were synthesized previously (22, 24, 25). Diisopropylphosphofluoridate, tetracaine, Carb, PCP, propofol, proadifen, and CNBr were from Sigma-Aldrich. [3H]ACh (30 Ci/mmol) was synthesized by esterification of choline and [3H]acetic anhydride. [3H]TCP (58 Ci/mmol) and [3H]tetracaine (30 Ci/mmol) were obtained from PerkinElmer Life Sciences and Sibtech (Newington, CT), respectively. Staphylococcus aureus endopeptidase Glu-C (V8 protease) was from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH), l-1-tosylamido-2-phenylethyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-treated trypsin was from Worthington, Lysobacter enzymogenes endoproteinase Lys-C (EndoLys-C) was from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN), and o-phthalaldehyde (OPA) was from Alfa Aesar. All other chemicals were obtained from standard commercial sources.

Radioligand binding assays

Equilibrium binding of [3H]ACh, [3H]TCP, or [3H]tetracaine to Torpedo nAChR-rich membranes in Torpedo physiological saline buffer (250 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 3 mm CaCl2, 2 mm MgCl2, and 5 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.0) was determined by centrifugation as described (45). In brief, membrane suspensions were pre-equilibrated with radioligand for 30 min on ice and then incubated with various concentrations of non-radioactive drugs for 1 h at 4 °C before centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 45 min. After removal of the supernatants, membrane pellets were resuspended in 200 μl of 10% SDS overnight, with pellet and supernatant 3H determined by liquid scintillation counting. For [3H]ACh binding, membrane suspensions (40 nm ACh-binding sites) were pretreated with 0.5 mm diisopropylphosphofluoridate for 15 min to inhibit acetylcholinesterase activity before incubation with 4 nm [3H]ACh. [3H]TCP and [3H]tetracaine binding was determined with membrane suspensions containing 500 nm ACh-binding sites and 10 nm radioligand. For [3H]TCP binding, nAChRs were stabilized in the desensitized state by preincubation for 30 min with the agonist Carb at 1 mm. For [3H]tetracaine, membranes were preincubated with the competitive antagonist α-bungarotoxin at 5 μm to stabilize nAChRs in the resting, closed channel state. Nonspecific binding of [3H]ACh, [3H]TCP, or [3H]tetracaine was determined in the presence of 100 μm Carb, PCP, or tetracaine, respectively.

For each radioligand, fx, the specifically bound 3H (cpmtotal − cpmnonspecific) in the presence of competitor at concentration x, was normalized to f0, the specifically bound 3H in the absence of competitor. The concentration-dependent enhancement of [3H]ACh binding was fit using non-linear least squares regression (SigmaPlot version 11) to the equation, fx/f0 = 100 + Emax/(1 + EC50/x), and inhibition of [3H]TCP or [3H]tetracaine binding was fit to the equation, fx/f0 = 100/(1 + x/IC50), where EC50 and IC50 are the ligand concentrations producing half-maximal enhancement or inhibition, and Emax is the maximal enhancement of [3H]ACh binding.

[3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeling and gel electrophoresis

[3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeling of Torpedo nAChR-rich membranes (0.9 nmol of ACh-binding sites/mg of protein; 2 mg of protein/ml in Torpedo physiological saline buffer supplemented with 1 mm oxidized glutathione as an aqueous scavenger) was performed at 4 °C on analytical or preparative scales using 0.1 or 10 mg of protein per condition, respectively. After incubation with [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB (0.4–0.9 μm) for 30 min and an additional 30-min incubation in the absence or presence of other ligands, the membranes on ice were irradiated for 30 min using a 365-nm UV lamp (model EN-280L, Spectronics Corp., Westbury, NJ) at a distance of <2 cm. After photolabeling, membrane polypeptides were resolved by Tris-glycine SDS-PAGE on gels composed of 8% polyacrylamide, 0.33% bisacrylamide and visualized with GelCodeTM Blue Safe Protein Stain (ThermoFisher). For analytical photolabelings, duplicate samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, with stained subunit bands excised from one set for 3H quantification by liquid scintillation counting and the other set analyzed by fluorography using Amplify (GE Healthcare). For preparative photolabelings, bands containing the nAChR α, β, γ, and δ subunits were excised from the stained gels, and material was eluted passively for 3 days at room temperature in elution buffer (100 mm NH4HCO3, 2.5 mm dl-dithiothreitol, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.4). Eluted samples were filtered, concentrated to a final volume of <400 μl by centrifugal filtration using Vivaspin 15 Mr 5000 concentrators (Vivascience, Stonehouse, UK), precipitated by 75% acetone overnight at −20 °C, and resuspended in digestion buffer (15 mm Tris, 0.5 mm EDTA, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.1). For most preparative photolabelings, only 25% of the α and γ subunit gel bands were eluted, with 75% of those gel bands used for in-gel digestion with V8 protease (100 μg) on 15% polyacrylamide, 0.76% bisacrylamide mapping gels (32, 40). The resultant subunit fragments (αV8-20, αV8-10, γV8-24, and γV8-14) were recovered from gel bands by passive elution, concentrated, and resuspended in digestion buffer. In addition, α subunits from Torpedo nAChR-rich membranes (0.5 mg of protein) photolabeled on an analytical scale with 1.5 μm [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB were digested in gel by V8 protease (5 μg), with 3H distribution in the fragments determined by liquid scintillation counting.

Proteolytic digestions

All enzymatic digestions were performed at room temperature. From preparative labelings, ∼50% of eluted α and β subunits and 100% of αV8-10 in digestion buffer were diluted 5-fold with 50 mm NH4HCO3 (pH 8.1) containing 0.5% Genapol to reduce the SDS concentration to 0.02% and then digested with 200 μg of TPCK-treated trypsin in the presence of 0.4 mm CaCl2 overnight (β subunit) or for 2–3 days (α subunit and αV8-10). αV8-20, γV8-24, γV8-14, and 60% of δ subunit in digestion buffer were digested with 0.5 units of EndoLys-C for 2 weeks. Aliquots of β (50%), γ (25%), and δ (40%) subunits were digested with 200 μg of V8 protease for 2–3 days in digestion buffer. Small pore Tricine SDS-PAGE gels (16.5% T, 6% C) (36, 53) were used to fractionate the β and δ subunits after digestion in solution with trypsin and EndoLys-C, respectively. The resultant fragments were recovered from Tricine gel bands by passive elution and concentrated by centrifugation for the further purification by rpHPLC.

rpHPLC and sequence analyses

rpHPLC was performed as described (45) using an Agilent 1100 binary rpHPLC system, a Brownlee Aquapore BU-300 column, and a mobile phase consisting of aqueous solvent A (0.08% trifluoroacetic acid) and organic solvent B (3:2 acetonitrile/isopropyl alcohol and 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid). Material was eluted at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min using a non-linear gradient with solvent B increasing from 25 to 100% over 90 min. Fractions were collected every 2.5 min, and 3H was deterimined by counting 10%.

rpHPLC fractions containing αM1, αM4, or δM1 were loaded onto PVDF membrane filters using Applied Biosystems ProSorbTM sample preparation cartridges. All other rpHPLC fractions containing 3H-labeled peptides were drop-loaded onto the Applied Biosystems Micro TFA glass fiber filters at 45 °C. Samples were treated with Biobrene Plus after loading to stabilize the peptides on the filters and then sequenced on an Applied Biosystems Procise 492 protein sequencer. For certain samples, sequencing was interrupted at predetermined cycles to treat the filter with OPA to prevent further sequencing of other peptides not containing a proline at that cycle (52, 54). To facilitate identification of [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB photolabeling in αM1, samples containing the fragment beginning at αHis-186 were sequenced for 15 cycles, and filters were then treated with CNBr as described (17, 55) to cleave at the C-terminal side of αMet-207 before αM1.

During N-terminal sequencing, two-thirds of the material was injected into an rpHPLC system for quantifying the amino acid at each cycle, and one-third of the sample was collected for determination of 3H release. The masses of released phenylthiohydantoin (PTH)-amino acid derivatives were fit versus cycles of Edman degradation (SigmaPlot version 11) according to the equation, fx = I0 × Rx, where fx is the mass of amino acid on cycle x, I0 is the initial mass of the peptide, and R is the repetitive yield of Edman degradation. The labeling efficiencies (cpm/pmol) of residues photolabeled by [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB were calculated based on the expression, (2 × (cpmx − cpm(x − 1)))/(I0 × Rx).

Computational docking

A homology model of the T. californica nAChR was constructed based on the recently solved (3.9 Å) crystal structure of a neuronal (α4)2(β2)3 nAChR (Protein Data Bank entry 5KXI (16)) using the Create Homology Model tool in Discovery Studio 2017 (Biovia). Torpedo α sequences were substituted for the two α4 subunits, and the three β2 subunits were replaced with Torpedo β, γ, and δ subunits in their known positions relative to the α subunits (i.e. clockwise αβδαγ when viewed from the extracellular side). The α4 to α substitution required a single-residue insert in loop C of the agonist binding site (Torpedo αThr-196). To align the Torpedo β, γ, and δ subunits with β2, the following adjustments were made. (i) For β and γ subunits, β2Pro-14 and β2Ser-15 were deleted. (ii) Insertions were made between β2Glu-165 and β2Val-166 of 10 (β), 8 (γ), or 12 (δ) residues in the structurally undefined agonist site loop F region. Because the structures of these large inserts are unknown, these inserts were removed from the model before docking. (iii) Four residue insertions were made in γ and δ subunit loop C regions between β2Asp-192 and β2Asp-193. (iv) A single residue was inserted for γ in the M1-M2 loop between β2Cys-237 and β2Gly-238. Nicotine molecules bound to the two agonist sites in the α4β2 structure were retained in the homology model. The model was placed in a membrane force field, and the entire model was minimized to −85,106 kcal/mol.

Initial attempts to dock S-mTFD-MPPB to a pocket between the M1, M2, and M3 helices at the extracellular end of the α or δ transmembrane helix bundles were unsuccessful. To create a pocket in this region, S-mTFD-MPPB was placed within the helix bundle between M1, M2, and M3 adjacent to the labeled residues (for both α and δ subunits), and the model was minimized to −107,840 and −84,853 kcal/mol for α and δ subunits, respectively. A binding site sphere of 12-Å radius was placed around the minimized S-mTFD-MPPB, and the sphere was seeded with 12 copies each of S-mTFD-MPPB and R-mTFD-MPAB. Each seeded molecule was subjected to 40 molecular dynamics-induced alterations, and each altered structure was rotated/translated into 40 different starting orientations. Each sampling was minimized with the residues within the sphere, the final interaction energy was determined, and the lowest-energy solutions were collected along with the predicted orientations of the bound molecules. S-mTFD-MPPB and R-mTFD-MPAB were also docked using 12-Å binding site spheres in the pocket at the γ–α interface and at three levels in the ion channel using binding site spheres centered at M2-2′, M2-6′/9′, and M2-13′/17′. For individual binding sites, docking results are displayed as Connolly surface representations defined by a 1.4-Å diameter probe of the 10 solutions with the lowest CDOCKER interaction energies.

Author contributions

Z. Y. and J. B. C. designed and analyzed the experiments that were performed by Z. Y. Both authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Pavel Savechenkov and Prof. Karol Bruzik (University of Illinois, Chicago) for providing R- and S-mTFD-MPPB and [3H]S-mTFD-MPPB. We also thank Drs. David Chiara and Selwyn Jayakar for useful advice during the course of these studies and for comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM-58448 (to J. B. C.) and by the Edward and Anne Lefler Center of Harvard Medical School. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- nAChR

- nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- PAM

- positive allosteric modulator

- TMD

- transmembrane domain

- mTFD-MPPB

- 1-methyl-5-propyly-5-(m-trifluoromethyl-diazirinylphenyl) barbituric acid

- R-mTFD-MPAB

- R-1-methyl-5-allyl-5-(m-trifluoromethyl-diazirinylphenyl) barbituric acid

- GABAAR

- γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor

- Carb

- carbamylcholine

- PCP

- phencyclidine

- TCP

- tenocyclidine

- ACh

- acetylcholine

- AziPm

- 2-isopropyl-5-[3-(trifluoromethyl)-3H-diazirin-3-yl]phenol

- TID

- 3-(trifluoromethyl)-3-(m-iodophenyl)diazirine

- V8 protease

- S. aureus endopeptidase Glu-C

- EndoLys-C

- L. enzymogenes endoproteinase Lys-C

- TPCK

- l-1-tosylamido-2-phenylethyl chloromethyl ketone

- OPA

- o-phthalaldehyde

- PTH

- phenylthiohydantoin

- rpHPLC

- reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography

- Tricine

- N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine.

References

- 1. Changeux J. P. (2012) The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: the founding father of the pentameric ligand-gated ion channel superfamily. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 40207–40215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sigel E., and Steinmann M. E. (2012) Structure, function, and modulation of GABAA receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 40224–40231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dutertre S., Becker C. M., and Betz H. (2012) Inhibitory glycine receptors: an update. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 40216–40223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lummis S. C. R. (2012) 5-HT3 receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 40239–40245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wolstenholme A. J. (2012) Glutamate-gated chloride channels. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 40232–40238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jensen A. A., Frølund B., Liljefors T., and Krogsgaard-Larsen P. (2005) Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: structural revelations, target identifications, and therapeutic inspirations. J. Med. Chem. 48, 4705–4745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Taly A., Corringer P. J., Guedin D., Lestage P., and Changeux J. P. (2009) Nicotinic receptors: allosteric transitions and therapeutic targets in the nervous system. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 8, 733–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hurst R., Rollema H., and Bertrand D. (2013) Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: from basic science to therapeutics. Pharmacol. Ther. 137, 22–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Williams D. K., Wang J., and Papke R. L. (2011) Positive allosteric modulators as an approach to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-targeted therapeutics: advantages and limitations. Biochem. Pharmacol. 82, 915–930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chatzidaki A., and Millar N. S. (2015) Allosteric modulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 97, 408–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hamouda A. K., Wang Z. J., Stewart D. S., Jain A. D., Glennon R. A., and Cohen J. B. (2015) Desformylflustrabromine (dFBr) and [3H]dFBr-labeled binding sites in a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 88, 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hamouda A. K., Deba F., Wang Z. J., and Cohen J. B. (2016) Photolabeling a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) with an (α4)3(β2)2 nAChR-selective positive allosteric modulator. Mol. Pharmacol. 89, 575–584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rucktooa P., Smit A. B., and Sixma T. K. (2009) Insight in nAChR subtype selectivity from AChBP crystal structures. Biochem. Pharmacol. 78, 777–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Olsen J. A., Ahring P. K., Kastrup J. S., Gajhede M., and Balle T. (2014) Structural and functional studies of the modulator NS9283 reveal agonist-like mechanism of action at α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 24911–24921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nemecz Á., Prevost M. S., Menny A., and Corringer P. J. (2016) Emerging molecular mechanisms of signal transduction in pentameric ligand-gated ion channels. Neuron 90, 452–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Morales-Perez C. L., Noviello C. M., and Hibbs R. E. (2016) X-ray structure of the human α4β2 nicotinic receptor. Nature 538, 411–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hamouda A. K., Kimm T., and Cohen J. B. (2013) Physostigmine and galanthamine bind in the presence of agonist at the canonical and noncanonical subunit interfaces of a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. J. Neurosci. 33, 485–494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sieghart W. (2015) Allosteric modulation of GABAA receptors via multiple drug-binding sites. Adv. Pharmacol. 72, 53–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Puthenkalam R., Hieckel M., Simeone X., Suwattanasophon C., Feldbauer R. V., Ecker G. F., and Ernst M. (2016) Structural studies of GABA-A receptor binding sites: which experimental structure tells us what? Front. Mol. Neurosci. 9, 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hamouda A. K., Jayakar S. S., Chiara D. C., and Cohen J. B. (2014) Photoaffinity labeling of nicotinic receptors: diversity of drug binding sites! J. Mol. Neurosci. 53, 480–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Forman S. A., Chiara D. C., and Miller K. W. (2015) Anesthetics target interfacial transmembrane sites in nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuropharmacology 96, 169–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Savechenkov P. Y., Zhang X., Chiara D. C., Stewart D. S., Ge R., Zhou X., Raines D. E., Cohen J. B., Forman S. A., Miller K. W., and Bruzik K. S. (2012) Allyl m-trifluoromethyldiazirine mephobarbital: an unusually potent enantioselective and photoreactive barbiturate general anesthetic. J. Med. Chem. 55, 6554–6565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chiara D. C., Jayakar S. S., Zhou X., Zhang X., Savechenkov P. Y., Bruzik K. S., Miller K. W., and Cohen J. B. (2013) Specificity of intersubunit general anesthetic-binding sites in the transmembrane domain of the human α1β3γ2 γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 19343–19357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Desai R., Savechenkov P. Y., Zolkowska D., Ge R. L., Rogawski M. A., Bruzik K. S., Forman S. A., Raines D. E., and Miller K. W. (2015) Contrasting actions of a convulsant barbiturate and its anticonvulsant enantiomer on the α1β3γ2L GABAA receptor account for their in vivo effects. J. Physiol. 593, 4943–4961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jayakar S. S., Zhou X., Savechenkov P. Y., Chiara D. C., Desai R., Bruzik K. S., Miller K. W., and Cohen J. B. (2015) Positive and negative allosteric modulation of an α1β3γ2 γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptor by binding to a site in the transmembrane domain at the γ+-β− interface. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 23432–23446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hamouda A. K., Stewart D. S., Chiara D. C., Savechenkov P. Y., Bruzik K. S., and Cohen J. B. (2014) Identifying barbiturate binding sites in a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with [3H]allyl m-trifluoromethyldiazirine mephobarbital, a photoreactive barbiturate. Mol. Pharmacol. 85, 735–746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boyd N. D., and Cohen J. B. (1984) Desensitization of membrane-bound Torpedo acetylcholine receptor by amine noncompetitive antagonists and aliphatic alcohols: studies of [3H]-acetylcholine binding and 22Na+ ion fluxes. Biochemistry 23, 4023–4033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Katz E. J., Cortes V. I., Eldefrawi M. E., and Eldefrawi A. T. (1997) Chlorpyrifos, parathion, and their oxons bind to and desensitize a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: relevance to their toxicities. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 146, 227–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Arias H. R., Trudell J. R., Bayer E. Z., Hester B., McCardy E. A., and Blanton M. P. (2003) Noncompetitive antagonist binding sites in the Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ion channel. structure-activity relationship studies using adamantane derivatives. Biochemistry 42, 7358–7370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moore M. A., and McCarthy M. P. (1995) Snake venom toxins, unlike smaller antagonists, appear to stabilize a resting state conformation of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1235, 336–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Middleton R. E., Strnad N. P., and Cohen J. B. (1999) Photoaffinity labeling the Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with [3H]tetracaine, a nondesensitizing noncompetitive antagonist. Mol. Pharmacol. 56, 290–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. White B. H., and Cohen J. B. (1988) Photolabeling of membrane-bound Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with the hydrophobic probe 3-trifluoromethyl-3-(m-[125I]iodophenyl)diazirine. Biochemistry 27, 8741–8751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pratt M. B., Husain S. S., Miller K. W., and Cohen J. B. (2000) Identification of sites of incorporation in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor of a photoactivatible general anesthetic. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 29441–29451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Unwin N. (2005) Refined structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at 4 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 346, 967–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jayakar S. S., Dailey W. P., Eckenhoff R. G., and Cohen J. B. (2013) Identification of propofol binding sites in a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with a photoreactive propofol analog. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 6178–6189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Arevalo E., Chiara D. C., Forman S. A., Cohen J. B., and Miller K. W. (2005) Gating-enhanced accessibility of hydrophobic sites within the transmembrane region of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor's δ-subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 13631–13640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jayakar S. S., Zhou X., Chiara D. C., Dostalova Z., Savechenkov P. Y., Bruzik K. S., Dailey W. P., Miller K. W., Eckenhoff R. G., and Cohen J. B. (2014) Multiple propofol-binding sites in a γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor (GABAAR) identified using a photoreactive propofol analog. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 27456–27468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. White B. H., and Cohen J. B. (1992) Agonist-induced changes in the structure of the acetylcholine receptor M2 regions revealed by photoincorporation of an uncharged nicotinic non-competitive antagonist. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 15770–15783 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chiara D. C., Hamouda A. K., Ziebell M. R., Mejia L. A., Garcia G. 3rd, and Cohen J. B. (2009) [3H]Chlorpromazine photolabeling of the Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor identifies two state-dependent binding sites in the ion channel. Biochemistry 48, 10066–10077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Blanton M. P., and Cohen J. B. (1994) Identifying the lipid-protein interface of the Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: secondary structure implications. Biochemistry 33, 2859–2872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hamouda A. K., Chiara D. C., Blanton M. P., and Cohen J. B. (2008) Probing the structure of the affinity-purified and lipid-reconstituted Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Biochemistry 47, 12787–12794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yamodo I. H., Chiara D. C., Cohen J. B., and Miller K. W. (2010) Conformational changes in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor during gating and desensitization. Biochemistry 49, 156–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chiara D. C., Dangott L. J., Eckenhoff R. G., and Cohen J. B. (2003) Identification of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor amino acids photolabeled by the volatile anesthetic halothane. Biochemistry 42, 13457–13467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nirthanan S., Garcia G. 3rd, Chiara D. C., Husain S. S., and Cohen J. B. (2008) Identification of binding sites in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor for TDBzl-etomidate, a photoreactive positive allosteric effector. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 22051–22062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hamouda A. K., Stewart D. S., Husain S. S., and Cohen J. B. (2011) Multiple transmembrane binding sites for p-trifluoromethyldiazirinyl-etomidate, a photoreactive Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor allosteric inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 20466–20477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pandhare A., Hamouda A. K., Staggs B., Aggarwal S., Duddempudi P. K., Lever J. R., Lapinsky D. J., Jansen M., Cohen J. B., and Blanton M. P. (2012) Bupropion binds to two sites in the Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor transmembrane domain: a photoaffinity labeling study with the bupropion analogue [125I]-SADU-3-72. Biochemistry 51, 2425–2435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. de Armendi A. J., Tonner P. H., Bugge B., and Miller K. W. (1993) Barbiturate action is dependent on the conformational state of the acetylcholine receptor. Anesthesiology 79, 1033–1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cohen J. B., Correll L. A., Dreyer E. B., Kuisk I. R., Medynski D. C., and Strnad N. P. (1986) Interactions of local anesthetics with Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Anesthetics (Roth S. H., and Miller K. W., eds) pp. 111–124, Plenum, New York [Google Scholar]

- 49. Arias H. R., McCardy E. A., Gallagher M. J., and Blanton M. P. (2001) Interaction of barbiturate analogs with the Torpedo californica nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ion channel. Mol. Pharmacol. 60, 497–506 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Arias H. R., Kem W. R., Trudell J. R., and Blanton M. P. (2003) Unique general anesthetic binding sites within distinct conformational states of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 54, 1–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fourati Z., Ruza R. R., Laverty D., Drège E., Delarue-Cochin S., Joseph D., Koehl P., Smart T., and Delarue M. (2017) Barbiturates bind in the GLIC ion channel pore and cause inhibition by stabilizing a closed state. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 1550–1558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Middleton R. E., and Cohen J. B. (1991) Mapping of the acetylcholine binding site of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: [3H]-nicotine as an agonist photoaffinity label. Biochemistry 30, 6987–6997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schägger H., and von Jagow G. (1987) Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal. Biochem. 166, 368–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Brauer A. W., Oman C. L., and Margolies M. N. (1984) Use of o-phthalaldehyde to reduce background during automated Edman degradation. Anal. Biochem. 137, 134–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Scott M. G., Crimmins D. L., McCourt D. W., Tarrand J. J., Eyerman M. C., and Nahm M. H. (1988) A simple in situ cyanogen bromide cleavage method to obtain internal amino acid sequence of proteins electroblotted to polyvinyldifluoride membranes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 155, 1353–1359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]