Abstract

Background:

The efficacy of traditional medical treatments for alopecia areata (AA) is limited, leading some to pursue alternative treatments. The utilization and nature of these treatments are unclear.

Objective:

To assess the extent to which patients with AA pursue alternative treatments and to characterize these treatments.

Methods:

A 13-item electronic survey was E-mailed by the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (NAAF) to their patient database and shared on the NAAF social media to individuals with AA.

Results:

Of 1083 respondents, 78.1% of patients were very or somewhat unsatisfied, compared to 7.7% who were very or somewhat satisfied with the current medical treatments for AA. Approximately a third of patients pursued therapy-related mental health services (31.2%) and attended support groups (29.0%). Patients were more likely to pursue a mental health-related therapy if they had long-standing alopecia, or if they were young, female, or white.

Limitations:

This was a convenience sample of patients recruited online and via the NAAF AA registry.

Conclusion:

Many patients with AA are dissatisfied with current treatments and are seeking mental health treatment for AA. While the efficacy of alternative therapies is unknown, further research is needed to determine their role in the treatment of AA.

Key words: Alopecia areata, alopecia totalis, alopecia universalis, alternative, complementary, dermatology, emotional, hair loss, mental health, predictors, psychiatry, psychological, psychology, psychotherapy, satisfaction, support group, survey, therapy, treatments, unconventional

INTRODUCTION

Alopecia areata (AA) is a common autoimmune disease characterized by nonscarring patches of hair loss[1,2,3,4,5,6] and has an estimated global prevalence of 1.7%.[1,2,7,8] While most patients have disease limited to the scalp, approximately 1% of patients with AA have loss of all scalp and body hair (alopecia universalis, AU).[9] There is no cure for AA,[9,10,11] and treatments are limited with varying efficacy and tolerability.[5,6,12,13] Patients typically experience relapses following treatment, which is distressing and devastating to many patients.[14] Patients may turn to alternative modalities of care to alleviate the psychological burden of the condition.[15]

Complementary and alternative therapies are defined as treatments outside of the contemporary allopathic treatments including biofeedback,[16] cognitive behavioral therapy,[17] and support group use.[18,19] Little is known about patients' current satisfaction with medical treatments for AA, and less is known about their interest in and use of alternative treatments.

In this study, we aim to assess patient satisfaction with current medical treatments for AA and evaluate the levels of utilization of various alternative treatments for AA through a national survey, and to identify characteristics of individuals who use these alternative treatments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and setting

We administered a cross-sectional national survey between May 2016 and August 2016 to a convenience sample of adult individuals who had a diagnosis of AA from the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (NAAF) patient database. NAAF is a nonprofit organization dedicated to serving people impacted by AA through providing information and supporting research about AA. In addition, the survey was shared through NAAF's Twitter and Facebook profiles. Dartmouth College's Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (CPHS) and the Partners Human Research Committee (PHRC) considered this project exempt from Institutional Review Board review. All surveys were completed online and hosted by Qualtrics (Qualtrics LLC, Provo, Utah, USA).

Survey

A 13-item electronic survey was designed using Qualtrics and tested for usability and comprehension among a small group of patients. This survey consisted of questions organized into the following domains: demographics (age, gender, state of residence, race, ethnicity, and employment status), satisfaction with medical treatments, and pursuance of nonmedical treatments. All questions were developed to address the research aims of this study.

Administration

Anonymized links to the survey were shared by NAAF via E-mail to their patient database and posted publicly on their Facebook and Twitter platforms. The survey had two screening questions that eliminated patients younger than 18 years and respondents who indicated that they did not have AA. The estimated time to complete the survey was 15 min.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics on respondent characteristics and utilization of alternative treatments were calculated. Univariable logistic regression models tested for associations between patient characteristics and use of therapy for AA. Variables that were significant at P < 0.15 were included in a multivariable logistic regression model.

RESULTS

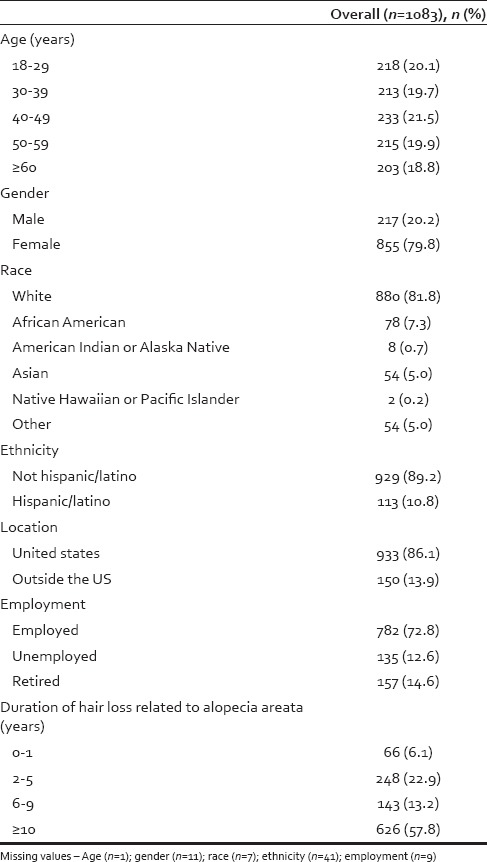

In total, 1184 responses were collected. Forty-six patients were excluded for being younger than 18 years old, and 83 patients were excluded for indicating that they did not have AA. Of the remaining 1083 respondents, the majority (n = 880, or 81.8%) were white and female (n = 855, or 79.8%) [Table 1]. Over half (n = 651, or 60.2%) of patients were 40 years of age or older, and the majority (n = 626, or 57.8%) of patients had alopecia for over 10 years.

Table 1.

Respondent demographics and characteristics

Satisfaction with current medical treatments

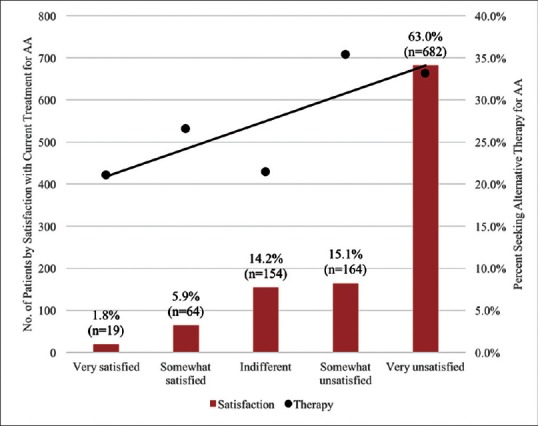

When asked “How satisfied are you with the current medical treatments for AA?” 78.1% (n = 846) of patients were somewhat unsatisfied or very unsatisfied, compared to 7.7% (n = 83) who were very or somewhat satisfied [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Patient satisfaction with current medical treatments. Respondents were asked, “How satisfied are you with the current medical treatments for alopecia areata?” Along the second Y-axis, the percent of respondents who sought alternative therapies are stratified by how satisfied they were with current medical treatments

Utilization of alternative treatments

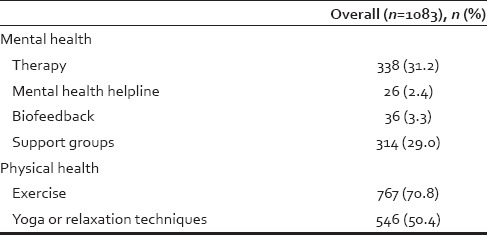

When asked, “Outside of medical treatments, have you done any of the following?” most patients pursued physical health-oriented alternative treatments such as exercise (n = 767, or 70.8%), while half of respondents tried yoga or another relaxation technique (n = 546, or 50.4%).

Nearly a third (n = 338, or 31.2%) of patients pursued therapy, including cognitive behavioral therapy, psychodynamic psychotherapy, supportive-expressive therapy, licensed counselor, psychiatrist, and psychologists [Table 2]. Support groups were attended by 29.0% (n = 314) of patients. Fewer of the respondents used biofeedback (n = 36, or 3.3%) and mental health helpline (e.g., suicide prevention hotline) (n = 26, or 2.4%).

Table 2.

Utilization of alternative treatments for alopecia areata

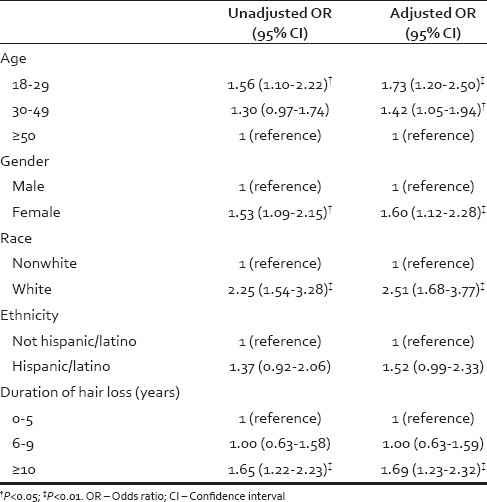

Predictors of seeking therapy

Adults aged 18–29 years were 1.73 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.20, 2.50) and adults aged 30–49 years were 1.42 (95% CI: 1.05, 1.94) times more to seek therapy (including cognitive behavioral therapy, psychodynamic psychotherapy, supportive-expressive therapy, licensed counselor, psychiatrist, and psychologists) for their AA than adults aged 50 years and over [Table 3]. Females were 1.60 (95% CI: 1.12, 2.28) times more likely than males to seek therapy. Whites were more likely to seek therapy than nonwhites (OR: 2.51, 95% CI: 1.68, 3.77). Patients who have had hair loss related to alopecia for 10 or more years were 1.69 (95% CI: 1.23, 2.32) times as likely to seek therapy than those with hair loss for 0–5 years.

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for patient characteristics associated with seeking therapy for alopecia areata

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that many patients with AA are dissatisfied with current medical treatments for their condition. A substantial number of respondents sought mental health services including therapy (including cognitive behavioral therapy, psychodynamic psychotherapy, supportive-expressive therapy, licensed counselor, psychiatrist, and psychologist) to aid in the management of their disease. Patients who are younger, female, or white were more likely to seek these forms of mental health services. Patients who have had hair loss for over 10 years were also more likely to seek therapy.

This study aligns with previous research that has shown that women are more likely than men to seek psychiatric support such as therapy and counseling for their mental health concerns.[20] Research has also shown that whites are more likely than nonwhites to pursue mental health care[21] and various forms of complementary and alternative medicine.[22]

Patients may be motivated to seek alternative care due to their dissatisfaction with traditional medical treatments. It is clear that patients with AA frequently demonstrate low health-related quality of life scores, with patients scoring lower the more extensive their hair loss.[23] Although some may use alternative treatments with the goal of regrowing hair, the majority of patients appear to participate in activities that aid in the management of the psychosocial and emotional burden of the condition.

These results must be considered within the context of the study design. Although this is the largest survey of alternative therapies in patients with AA to date, there are some limitations to this study. This was a nonrandomized convenience sample of patients, most of whom were recruited through the NAAF patient database. Consequently, we were unable to compare respondents to nonrespondents, or determine a survey response rate, allowing for potential selection bias in survey respondents. Our respondents were mostly white and female, while AA can impact both genders and all races. In addition, the respondents were more likely to have severe AA (81% of respondents described having hair loss across their body and not just on the scalp, as is most common) compared to the average patient with AA.[9] We were also unable to measure socioeconomic status, which may account for some differences in accessing alternative and mental health care resources.[24]

Future research should seek to confirm these data in the broader population and explore in depth the motivations of patients who seek alternative treatments. Despite their moderate level of utilization, there is a paucity of research investigating the efficacy of alternative therapies in the care for patients with AA. Ideally, this research will be integrated into current efforts to elucidate the pathophysiology of AA, and subsequent studies should evaluate the impact of alternative therapeutics on both clinical outcomes and disease biology. Specific emphasis should be made to understand quality of life improvements for patients, as these gains may not be necessarily linked to hair regrowth. Linking allopathic remedies with alternative therapeutics may prove to be the optimal approach for providing physical and mental relief for patients with AA.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hordinsky MK. Overview of alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2013;16:S13–5. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.2013.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alsantali A. Alopecia areata: A new treatment plan. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2011;4:107–15. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S22767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finner AM. Alopecia areata: Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and unusual cases. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:348–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2011.01413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grahovac T, Ruzic K, Sepic-Grahovac D, Dadic-Hero E, Radonja AP. Depressive disorder and alopecia. Psychiatr Danub. 2010;22:293–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Islam N, Leung PS, Huntley AC, Gershwin ME. The autoimmune basis of alopecia areata: A comprehensive review. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14:81–9. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacLean KJ, Tidman MJ. Alopecia areata: More than skin deep. Practitioner. 2013;257:29–32, 3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alkhalifah A, Alsantali A, Wang E, McElwee KJ, Shapiro J. Alopecia areata update: Part I. Clinical picture, histopathology, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:177–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kos L, Conlon J. An update on alopecia areata. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21:475–80. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32832db986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amin SS, Sachdeva S. Alopecia areata: A review. J Saudi Soc Dermatol Dermatol Surg. 2013;17:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shapiro J. Dermatologic therapy: Alopecia areata update. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:301. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2011.01422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hordinsky M, Donati A. Alopecia areata: An evidence-based treatment update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:231–46. doi: 10.1007/s40257-014-0086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madani S, Shapiro J. Alopecia areata update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:549–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Messenger AG, McKillop J, Farrant P, McDonagh AJ, Sladden M. British Association of Dermatologists' guidelines for the management of alopecia areata 2012. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:916–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunt N, McHale S. The psychological impact of alopecia. BMJ. 2005;331:951–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7522.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alkhalifah A, Alsantali A, Wang E, McElwee KJ, Shapiro J. Alopecia areata update: Part II. Treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shenefelt PD. Psychological interventions in the management of common skin conditions. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2010;3:51–63. doi: 10.2147/prbm.s7072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piaserico S, Marinello E, Dessi A, Linder MD, Coccarielli D, Peserico A. Efficacy of biofeedback and cognitive-behavioural therapy in psoriatic PatientsA Single-blind, randomized and controlled study with added narrow-band ultraviolet B therapy. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:91–5. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rolstad T, Zimmerman G. Patient advocacy groups. A key prescription for dermatology. Dermatol Clin. 2000;18:277–85, ix. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70173-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seng TK, Nee TS. Group therapy: A useful and supportive treatment for psoriasis patients. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:110–2. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1997.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oliver MI, Pearson N, Coe N, Gunnell D. Help-seeking behaviour in men and women with common mental health problems: Cross-sectional study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:297–301. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.4.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGuire TG, Miranda J. Racial and ethnic disparities in mental health care: Evidence and policy implications. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:393–403. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. National Health Statistics Reports: No. 12. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2008. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use among Adults and Children: United States, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu LY, King BA, Craiglow BG. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among patients with alopecia areata (AA): A systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;76:806–12.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chow JC, Jaffee K, Snowden L. Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of mental health services in poverty areas. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:792–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]