Abstract

Aims:

Tzanck smear is an old but useful test for diagnosis of cutaneous dermatoses. The aim of this study was to highlight the potential usefulness and diagnostic pitfalls of Tzanck smear for diagnosis of cutaneous dermatoses and infections.

Materials and Methods:

This hospital based cross-sectional study was carried out on all Tzanck smears received for a period of twenty months (January 2014–August 2015). The smears were assessed to establish the utility of Tzanck smears in corroborating or excluding a diagnosis of immunobullous lesion or herpetic infection. Cases with discrepant diagnosis on histopathology were reviewed to identify additional cytomorphological features.

Results:

A total of 57 Tzanck smears were performed during the study period. Out of the 18 clinically suspected cases of immunobullous disorders, Tzanck smear findings corroborated the clinical diagnosis in 7/18 cases, one case was diagnosed as cutaneous candidiasis, and diagnosis of immunobullous lesions could be excluded in 5/18 cases. Out of the 19 suspected cases of herpetic infections, viral cytopathic effect was observed in 8/19 cases. Besides immunobullous lesions and herpetic infections, acantholytic cells were also observed in spongiotic dermatitis and genodermatosis. Dyskeratotic keratinocytes seen in vacuolar interface dermatitis were not easily distinguishable from acantholytic cells on Tzanck smear.

Conclusions:

Tzanck smear test is an inexpensive and useful diagnostic tool for certain skin diseases. It can aid in establishing a rapid clinical diagnosis and can serve as a useful adjunct to routine histological examination. We recommend the use of Tzanck smear as a first-line investigation for vesiculobullous, erosive, and pustular lesions.

Keywords: Acantholysis, immunobullous, Tzanck smear, viral cytopathic effect

INTRODUCTION

Tzanck smear was first introduced in 1947 by Frenchman Tzanck as a tool of diagnostic cytology for diagnosis of vesiculobullous conditions, especially herpes simplex.[1,2] With time it evolved and Tzanck smear findings for several other dermatological conditions like immunobullous disorders, genodermatosis, cutaneous infections, and cutaneous tumors have also been described.[3] This test offers the advantage of being a simple, fast, and inexpensive diagnostic test but it requires certain amount of skill and experience for accurate interpretation.[4] The technique of this test is simple that can be performed with minimal patient discomfort or cost. It provides a helpful aid for corroboration or exclusion of a clinically suspected diagnosis. A positive Tzanck smear result can lead to rapid confirmation of the diagnosis of herpetic infection, even when viral culture fails. Presence of acantholytic cells or typical Tzanck-like cells in Tzanck smears can suggest a diagnosis of pemphigus group of diseases. Skin is the largest desquamating organ and though exfoliative cytology is routinely used for diagnosis in other medical and surgical specialties, but studies on cutaneous cytology remain limited. Certain studies have been published in Western literature regarding the accuracy and diagnostic reliability of Tzanck smear.[5,6] However, there is a paucity of studies in Indian literature regarding the utility and limitations of Tzanck smear cytology for different groups of dermatological diseases.[7] The aim of this study is to highlight the potential usefulness and diagnostic pitfalls of Tzanck smear for diagnosis of various types of dermatoses and cutaneous infections.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

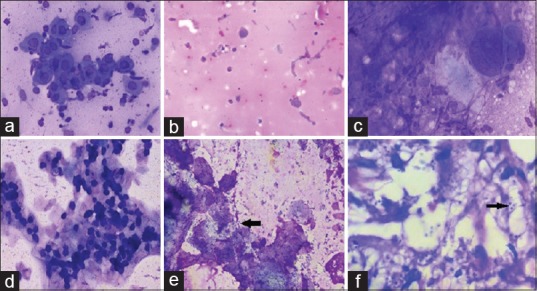

This hospital based cross-sectional study was carried out in the departments of Dermatology and Pathology at a tertiary care hospital. All Tzanck smears received for a period of twenty months (January 2014–August 2015) were included in the study. All consecutive patients with suspected infectious (Herpes simplex, Herpes Zoster, Varicella, Molluscum contagiosum) and non-infectious vesiculobullous/vesiculopustular diseases (both with intraepidermal bullae like pemphigus group and subepidermal bullae like pemphigoid), visiting the dermatology outdoor clinics were included in the study. An informed consent was obtained from all the patients. Non-consenting patients were excluded from the study. Clinical and demographic details of all the consenting patients were recorded. Tzanck smear was then prepared by gentle scraping from the base of a fresh vesicle, blister, or pustule or directly from the crusted lesion. For suspected viral infections, samples were taken from a fresh vesicle, rather than a crusted one, to ensure maximum yield of viral infected cells. In other vesiculobullous lesions, the vesicle was unroofed, and the base of the lesion was gently scraped with a scalpel or the edge of a spatula. The material thus obtained was smeared onto two microscopic slides. Both air dried and alcohol-fixed smears were prepared and subsequently stained with Wright–Giemsa and Papanicolaou stains, respectively. The stained smears were subsequently examined under light microscope for identification of viral cytopathic effect, acantholytic cells, inflammatory cells, and any other cutaneous infection. Suggestive diagnosis of pemphigus was given after observing many acantholytic cells and typical Tzanck cells [Figure 1a]. Numerous eosinophils were seen in addition to acantholytic cells in cases diagnosed as pemphigoid lesions [Figure 1b].

Figure 1.

(a) Multiple acantholytic cells seen in pemphigus vulgaris (Wright-Giemsa stain, ×400). (b) Occasional acantholytic cells with predominance of eosinophils in bullous pemphigoid (Pap stain ×200). (c) Viral cytopathic effect with multinucleation, ground glass nuclei, and nuclear moulding (Wright-Giemsa stain, ×400). (d) Keratinocytes showing intracytoplasmic basophilic inclusions (Molluscum bodies) (Pap stain ×200). (e) Candidiasis showing multiple budding yeast forms (Black arrow) (Pap stain ×400). (f) Cutaneous Leishmaniosis showing intracellular Leishmanial bodies ingested by macrophages (Black arrow) (Pap stain ×1000)

The study was carried out after due approval from the Human Ethics Committee of the Institute.

RESULTS

A total of 57 Tzanck smears were performed during the study period. Age of patients ranged from 10–80 years. Most patients clinically presented with vesiculo-pustular lesions. Mucosal involvement was predominantly seen in pemphigus vulgaris. Out of 57 cases, the findings of Tzanck smears were suggestive of immunobullous lesions in 9 cases and that of viral infections in 10 cases (Herpes and Varicella infections found in 8 cases, two were diagnosed as molluscum contagiosum). One case each was diagnosed as candidiasis and cutaneous leishmaniasis [Table 1]. Histopathological data was available for 20/57 lesions.

Table 1.

Details of Tzanck smear diagnosis

Out of the 18 clinically suspected cases of immunobullous disorders, Tzanck smear findings corroborated the clinical diagnosis in 7/18 cases, one case was diagnosed as cutaneous candidiasis, and diagnosis of immunobullous lesions could be excluded in 5/18 cases. Smears of cases diagnosed as pemphigus vulgaris revealed multiple typical acantholytic cells (Tzanck cells) described as large round keratinocytes having hyperchromatic nucleus with perinuclear halo and deep basophilic cytoplasm. Histopathological examination was done in 13/18 suspected cases of immunobullous lesions.

Out of the 19 suspected cases of herpetic infections (simplex/varicella/zoster), characteristic viral cytopathic effects were observed in 8/19 cases. These smears displayed multinucleated cells with ground glass nuclei, nuclear moulding, and margination of nuclear chromatin typical of herpes simplex and varicella infection [Figure 1c]. Six cases were diagnosed as acute inflammatory lesion; one of these lesions was diagnosed as paedrus dermatitis on histopathology, biopsy was not performed on the other 5 cases. Also, 2/3 cases suspected to be of molluscum contagiosum [Figure 1d] showed characteristic molluscum bodies on Tzanck smear. The other case did not show molluscum bodies on Tzanck smear, but showed presence of granulomas. Histology of this case subsequently turned out to be that of molluscum contagiosum.

One case diagnosed as candidiasis showed multiple budding yeast forms [Figure 1e]. Intracellular leishmania bodies were seen in the case diagnosed as cutaneous leishmaniasis [Figure 1f].

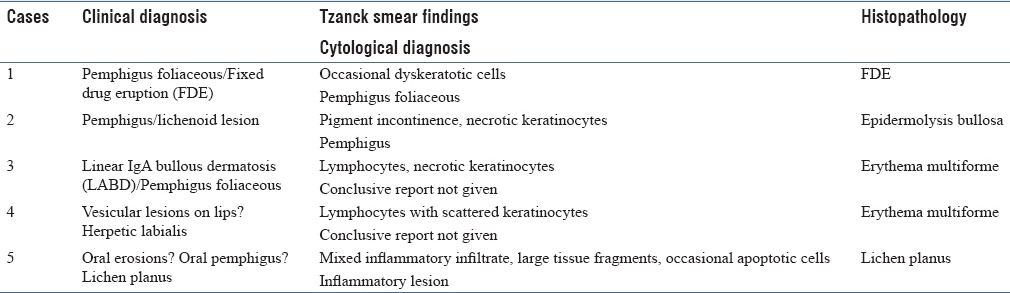

Table 2 depicts the histological diagnosis of those 5 cases where either a discrepant diagnosis or nonspecific findings were reported on Tzanck smear. These cases were reviewed to identify any additional cytomorphological details.

Table 2.

Pitfalls of Tzanck smears

DISCUSSION

The utility of Tzanck smear is no longer restricted to corroborate the diagnosis of pemphigus group of lesions and herpetic infections. It can even obviate the need of biopsy in certain cutaneous infections like molluscum contagiosum, candidiasis, and leishmaniasis. The findings of Tzanck smear should always be interpreted in appropriate clinical context to optimally utilize the benefits of this old but valuable technique.

Tzanck smear test is particularly helpful in providing a provisional diagnosis of Pemphigus vulgaris when the site of the lesion is not amenable for biopsy or the disease is in a very early stage.[3] Typical acantholytic cells are usually observed on Tzanck smear in cases of Pemphigus vulgaris, while other bullous lesions show scarcity of keratinocytes, absence of acantholytic cells, and relative predominance of inflammatory cells. Eosinophils are seen in abundance in cases of bullous pemphigoid.[3] Similar cytological features of pemphigus vulgaris and bullous pemphigoid were also noted in our study. Some authors have even suggested the use of direct immunofluroscence test for detection of immunoglobin deposits on Tzanck smear, to make the test more specific.[8]

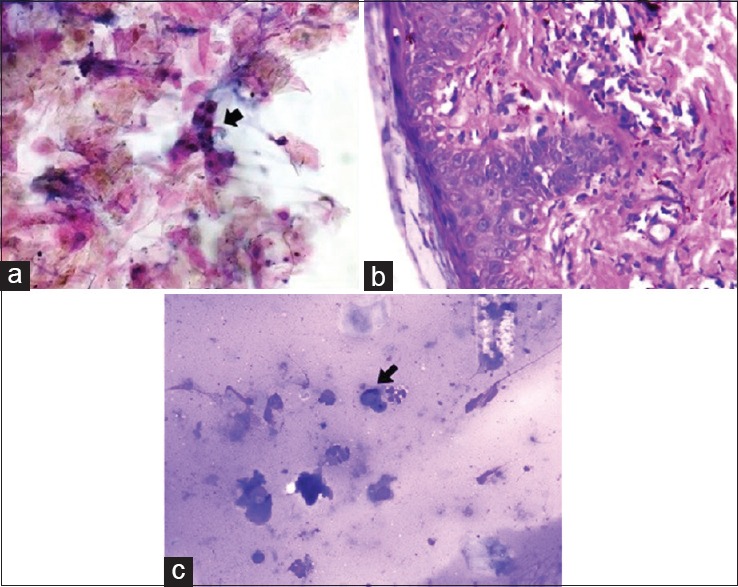

It may be difficult to differentiate dyskeratotic cells observed in lichen planus and fixed drug eruptions (FDE) from the acantholytic cells seen in pemphigus group of lesions. We encountered this diagnostic dilemma while reporting the Tzanck smear findings of a case where pemphigus foliaceous and FDE were the two clinical possibilities. Few clusters of dyskeratotic cells were observed on Tzanck smear, since pemphigus foliaceous usually shows fewer acantholytic cells and may show presence of dyskeratotic cells, we interpreted the case as pemphigus foliaceous. However, the histological features were consistent with FDE [Figure 2a and b]. Similar diagnostic challenge of differentiating necrotic keratinocytes and acantholytic cells was faced while interpreting the Tzanck cytology of a case where possibilities of lichen planus and oral pemphigus were being considered. Besides lichen planus and FDE, other common types of vacuolar interface dermatitis that may present as blisters are erythema multiformae (EM), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS). We encountered two cases of EM in our study, which showed lymphocytes in addition to necrotic keratinocytes. Tzanck smear findings of TEN and SSSS are well reported in the literature. In SSSS, the Tzanck smear shows many acantholytic keratinocytes without inflammatory cells, whereas smear in TEN shows few necrotic keratinocytes along with fibroblasts and inflammatory cells.[9] However, the morphological features of these entities should always be correlated with clinical features before giving a final diagnosis. Acantholytic cells were also observed on Tzanck smear in cases of spongiotic dermatitis and herpetic infections in our study.

Figure 2.

(a) Presence of dyskeratotic cells and occasional acantholytic cells in fixed drug eruptions in Tzanck smear (Black arrow) (Pap stain ×400). (b) Histopathology of fixed drug eruptions showing vacuolar interphase dermatitis with vacuolar degeneration at dermoepidermal junction and necrotic keratinocytes. (H and E stain ×400). (c) Presence of melanophages (Black arrow) in addition to necrotic keratinocytes and inflammatory cells in epidermolysis bullosa. (Wright-Giemsa stain, ×200)

Amongst the various genodermatosis, Tzanck smear cytology of Hailey–Hailey disease is described in literature, typical Tzanck cells are usually identified in this disease.[9] On reviewing the Tzanck smear cytology of a case of epidermolysis bullosa in our study, we could identify melanophages in addition to necrotic keratinocytes and inflammatory cells [Figure 2c]. Because some variants of epidermolysis bullosa can elicit a lichenoid reaction pattern, identification of pigment laden macrophages in such cases suggests damage to epidermal and dermal junction and abnormal dermal reactivity due to blister formation.[10]

Viral infections like herpes simplex are usually diagnosed clinically, but at times the clinical features may overlap with those of other venereal diseases or genital aphthous ulcers.[9] In such cases, Tzanck smears may be used as a useful diagnostic tool. Two cases were diagnosed as genital herpes in our study, one of these cases also showed presence of inflammatory atypia along with presence of acantholytic cells and multinucleated giant cells. The sensitivity and specificity of Tzanck smear for diagnosing herpetic infections has been compared with other techniques like polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and indirect immunofluorescence in various other studies.[11] Though PCR has better sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis, and species identification is not possible on Tzanck smear, this test is often recommended as an inexpensive but reliable diagnostic tool for diagnosing herpetic infections.[12]

Clinical features of molluscum contagiosum may sometimes overlap with other infections or milia, in such cases identification of typical molluscum bodies on Tzanck smear can be a useful diagnostic clue.[9] We also observed granulomatous reaction in one case of molluscum contagiosum, which has been only rarely described in literature. Granulomatous response may be attributed to rupture and discharge of contents of the molluscum bodies into the dermis.[13]

Tzanck smear cytology can aid the dermatologist in establishing clinical diagnosis with ease and rapidity and can serve as a useful adjunct to routine histologic study. Positive Tzanck smear test in infective conditions like herpes, molluscum, fungal and leishmaniasis enables the clinician to start treatment promptly. Similarly negative Tzanck smear test is equally useful in exclusion of certain diagnostic categories like pemphigus group of diseases.

Since Tzanck smear test is a simple and inexpensive technique and does not require a specialized laboratory setup, we recommend the use of Tzanck smear as a first-line investigation for vesiculobullous, erosive, and pustular lesions. Routine use of Tzanck smear in such lesions will help us in identifying cytological features for lesions other than immunobullous or infectious diseases.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tzanck A. Le cytodiagnostic immediate en dermatology. Ann Dermatol Syphiligr. 1947;7:68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Durdu M, Baba M, Seckin D. The value of Tzanck smear test in diagnosis of erosive, vesicular, bullous and pustular skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:958–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta LK, Singhi MK. Tzanck smear: A useful diagnostic tool. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:295–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grossman MC, Silvers DN. The Tzanck smear: Can dermatologists accurately interpret it? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:403–5. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70207-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solomon AR, Rasmussen JE, Weiss JS. A comparison of the Tzanck smear and viral isolation in varicella and herpes zoster. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:282–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eryılmaz A, Durdu M, Baba M, Yıldırım FE. Diagnostic reliability of the Tzanck smear in dermatologic diseases. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:178–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sabir F, Aziz M, Afroz N, Amin SS. Clinical and cyto-histopathological evaluation of skin lesions with special reference to bullous lesions. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:41–6. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.59181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aithal V, Kini U, Jayaseelan E. Role of direct immunofluorescence on Tzanck smears in pemphigus vulgaris. Diagn Cytopathol. 2007;35:403–7. doi: 10.1002/dc.20657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruocco E, Brunetti G, Del Vecchio M, Ruocco V. The practical use of cytology for diagnosis in dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:125–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cambiaghi S, Brusasco A, Restano L, Cavalli R, Tadini G. Epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa. Dermatology. 1997;195:65–8. doi: 10.1159/000245691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yaeen A, Ahmad QM, Farhana A, Shah P, Hassan I. Diagnostic value of Tzanck smear in various erosive, vesicular, and bullous skin lesions. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:381–6. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.169729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozcan A, Senol M, Saglam H, Seyhan M, Durmaz R, Aktas E, et al. Comparison of the Tzanck test and polymerase chain reaction in the diagnosis of cutaneous herpes simplex and varicella zoster virus infections. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:1177–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poojary SA, Kokane PT. Giant molluscum contagiosum with granulomatous inflammation and panniculitis: An unusual clinical and histopathological pattern in an HIV seropositive child. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2015;36:95–8. doi: 10.4103/2589-0557.156750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]