Abstract

Background and Aims

Premises licensed for the sale and consumption of alcohol can contribute to levels of assault‐related injury through poor operational practices that, if addressed, could reduce violence. We tested the real‐world effectiveness of an intervention designed to change premises operation, whether any intervention effect changed over time, and the effect of intervention dose.

Design

A parallel randomized controlled trial with the unit of allocation and outcomes measured at the level of individual premises.

Setting

All premises (public houses, nightclubs or hotels with a public bar) in Wales, UK.

Participants

A randomly selected subsample (n = 600) of eligible premises (that had one or more violent incidents recorded in police‐recorded crime data; n = 837) were randomized into control and intervention groups.

Intervention and comparator

Intervention premises were audited by Environmental Health Practitioners who identified risks for violence and provided feedback by varying dose (informal, through written advice, follow‐up visits) on how risks could be addressed. Control premises received usual practice.

Measurements

Police data were used to derive a binary variable describing whether, on each day premises were open, one or more violent incidents were evident over a 455‐day period following randomization.

Findings

Due to premises being unavailable at the time of intervention delivery 208 received the intervention and 245 were subject to usual practice in an intention‐to‐treat analysis. The intervention was associated with an increase in police recorded violence compared to normal practice (hazard ratio = 1.34, 95% confidence interval = 1.20–1.51). Exploratory analyses suggested that reduced violence was associated with greater intervention dose (follow‐up visits).

Conclusion

An Environmental Health Practitioner‐led intervention in premises licensed for the sale and on‐site consumption of alcohol resulted in an increase in police recorded violence.

Keywords: Alcohol, Environmental Health, intervention, licensed premises, randomized controlled trial, violence

Introduction

Premises licensed for the sale and on‐site consumption of alcohol and that are characterized by disorder typically feature lax door security, late licenses, poor risk management and other poor operating practices 1, 2, 3. In England and Wales it is estimated that 211 514 people attended health‐care services in 2014 for treatment following violence 4. Alcohol is involved with 47% of all violent offences 5 and an estimated 20% of all violence occurs in or around pubs, bars or nightclubs 6. While quasi‐experimental and similar studies suggest that intervention in premises can reduce harm 7, there is only limited evidence from methodologically sound trials to inform how policy can address violence, none of which have been conducted in the United Kingdom. Two systematic reviews of the international literature have been completed 8, 9. One review focused upon server training interventions, and concluded that research in the context of the licensed trade should be broadened to develop interventions that address multiple risk factors across the full socio‐ecological environment 9. The second 8 included a broader range of approaches, but only identified five randomized controlled trials, many of which were methodologically weak (poorly defined outcomes, ad‐hoc follow‐up periods, no consideration of intervention sustainability, inappropriate control groups and failure to achieve random allocation). Moreover, a significant barrier to research and development in this area is the unwillingness of premises to engage. An earlier feasibility study 10 found that 5% of premises invited into a voluntary harm reduction initiative engaged.

The aim of the All‐Wales Licensed Premises Intervention (AWLPI) was to evaluate the effectiveness of the SMILE (Safety Management in the Licensed Environment) intervention, designed to reduce violence in licensed premises. SMILE included a risk audit to identify areas of operation associated with violence, which prompted feedback on how operations could be improved to address risks. The primary objective was to (1) compare the day‐by‐day rate of violence in premises that receive the intervention to those that received usual practice during a 455‐day follow‐up period. Secondary objectives included (2) analysis of change in the rate of violence over time during the follow‐up period that any intervention effect might take time to bed in or wane. We further sought to (3) explore intervention dose on outcomes. An embedded process evaluation assessed fidelity, reach, acceptability and dose, results from which are available elsewhere 11.

Methods

The study was approved by the Cardiff University Dental School Research Ethics Committee (Reference 12/08). It was undertaken and reported in accordance with the Consolidated Standards Of Reporting Trial (CONSORT) 12. Details of pre‐registered hypotheses, design, intervention development and logic models are available elsewhere 10, 11, 13.

Study design and participants

This was a parallel randomized controlled trial where premises were randomized into two groups: control and intervention. Premises in the intervention group received the SMILE intervention; no contact was made with control premises who received usual practice. Police violent crime data were used to describe whether violence was present (denoting failure in premises operation) or not following randomization and daily for 455 days. These longitudinal data were then used to determine whether there were differences in the rate of failure across control and intervention groups. SMILE was delivered by Environmental Health Practitioners (EHPs), who are employed by local authorities (LAs) to protect public health by enforcing legislation and provide support. EHPs work mainly with health and safety legislation, which is applicable to all businesses whether licensed or not, and they have a ‘violence in the work‐place’ remit. While EHPs had little experience working with licensed premises 11, they had regulatory powers that enabled their entry into premises, needed to overcome the expected unwillingness of premises to engage 9, and they are trained to conduct work‐place risk assessments 14. Premises were not able to opt out of the study. SMILE was designed to work within EHPs’ statutory remit and to translate the applicable research base to inform activity. The underlying logic of the intervention recognized that violence arises through a complex interaction between place, person and social norms 15. As perpetrators are probably intoxicated, appealing to personal control is less effective compared to modifying the premises environment 16. Our approach emphasized opportunity (e.g. perceived surveillance), guardianship (e.g. door security) and cues (e.g. the perceived acceptability of disorder) and EHPs were prompted to work with premises staff and managers to develop appropriate policy and procedures that mitigate the risk of violence.

Premises were eligible if they were licensed for the sale and onsite consumption of alcohol, were a public house, nightclub or hotel with a public bar and that between the months May 2011 to April 2012 had had one or more violent incidents recorded in police‐recorded crime data. Premises were excluded if they were cafes, restaurants or entertainment venues, such as sports facilities and concert halls. The police data used to select eligible premises did not identify premises that had changed purpose (e.g. from bar to restaurant) or had ceased trading. LA business rate data (these fees are paid only by businesses that are trading) were used to cross‐check all study premises and determine whether they ceased to trade in the follow‐up period and when. All premises were also telephoned by researchers to cross‐check eligibility. The control group received usual practice. As EHPs only visited licensed premises for food‐related matters, usual practice would include management by police and LA licensing teams, to which both control and intervention premises were exposed.

Materials

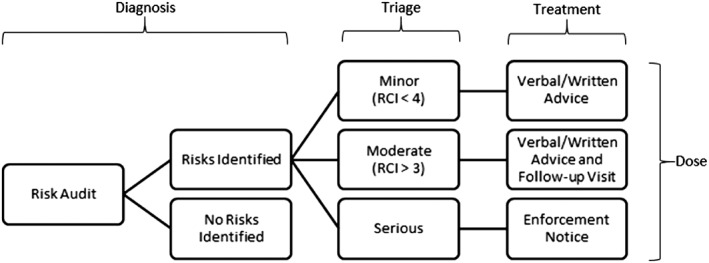

SMILE was developed from EHP usual practice 14, 17, and used existing audits and related measures used by EHPs as a template. All intervention premises received an audit that covered 11 areas of operation [Supporting information, Appendix S1]. For each area a Risk Control Indicator (RCI) scale that ranged from zero to seven was completed. Based on the RCI, EHPs determined the level of enforcement required to bring about change, and this increased from no feedback (no risk), verbal feedback, written advice, to follow‐up visits (RCI > 3) to enforce compliance (Fig. 1). For serious infringements that placed the public at risk formal notices could be issued. These placed a legal requirement on premises to comply and made them liable to punitive measures (e.g. fines). EHPs could also refer premises to partner agencies (police, licensing and fire) if they discovered risks that were not within their remit. EHPs’ usual approach requires that they intervene proportionately to the evidence for risk, with the emphasis on dialogue to assist those they regulate achieve compliance 17.

Figure 1.

Intervention components, risk control indicator (RCI) scores

Procedures

Senior EHPs piloted the intervention in 10 premises that were excluded from the main study. Minor revisions to intervention documentation were made. EHPs were trained in intervention delivery at one of three training sessions that included researchers, senior EHPs and consultants in emergency medicine who raised awareness of assault‐related injury, as EHPs were naive to the extent and severity of violence in this context. EHPs initially wrote to premises advising that they were to visit. When visiting they undertook a risk audit and provided feedback to premises staff on how identified risks could be addressed. Following the audit and feedback, additional materials were distributed to premises staff that included template policies and educational films.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome measure was police‐recorded violence (including homicide, violence with injury and violence without injury), notifiable offences that are reported to and recorded by the police. These data were collected independently by the four police forces in Wales; they contained the location, time and nature (using UK Home Office crime classification codes) of all violence in Wales, but were otherwise anonymous. For the baseline query eligible premises were identified through manually screening data. LA licensing teams and the premises themselves were telephoned by researchers to ensure that they were operational and met eligibility criteria. Using the baseline data as a training set, automated search algorithms were designed to screen follow‐up data and extract events associated with study premises. A random selection of 20% of these follow‐up data were also screened manually and compared. Events were scored 1 if they appeared in both data sets, otherwise 0; the proportion in agreement was 0.97.

The primary analysis was the comparison of failure rates between intervention and control premises during the follow‐up period with time 0 being 1 January 2013, the earliest date an audit could be delivered. While police‐recorded violence provided data for the primary outcome, a derivative of these data were used. Police data record violent events but do not indicate whether or not they are independent. We therefore ascribed each day using a binary indicator set to 1 when a day yielded one or more violent offences (indicating a failure in premises operation to prevent violence) and 0 otherwise. These longitudinal data facilitate an analytical approach that can include time‐varying covariates and account for when premises close temporarily or permanently (censoring). The primary data set used data extracted using automated search procedures; sensitivity analyses were conducted on data curated manually using the methods used to create the baseline data. Using the date and time of violent incidents, incidents were organized into sessions. A session was defined as 12 noon to 12 noon the following day and took the date of the first 12‐hour period.

Randomization

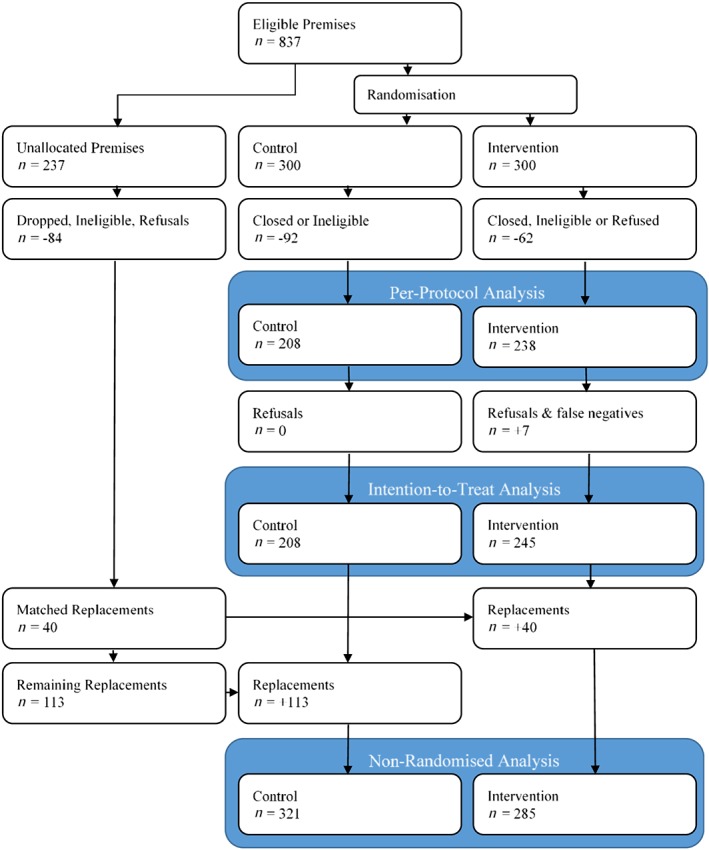

The total number of premises eligible for randomization was 837. An earlier exploratory trial used simulation on an assumed hazard rate of 0.9, based on pilot data, to estimate what overall group size (n = 274 premises) would be sufficient to provide a power of 90% to detect a relative 10% reduction in the failure rate at a significance level of 0.05 18. This was rounded up to 600 premises to account for premises ceasing business before the trial began. Premises were selected randomly from the total eligible population for randomization (the remaining unallocated premises were used later in additional sensitivity analyses; Fig. 2). Allocation to control and intervention groups was in a 1:1 ratio. Optimal allocation was used to carry out the randomization where a balancing algorithm minimized the imbalance between treatment groups across the pre‐specified balancing factors [opening hours: low (0–4 hours open after 11 p.m. across Friday and Saturday evening in total) versus high; number of baseline incidents: low (one or two incidents) versus high] on a block (LA) basis. This ensured that overall balance was maintained within blocks, and also between blocks by conditioning on the previous block allocation 19. LAs with greater capacity to carry out audits were not supplemented with other LA's premises, as EHPs do not go beyond their boundary. At the point of inclusion in the study, no one knew to which arm the premises would be randomized, and as randomization occurred at a single time‐point independently from the trial team and EHPs, allocation concealment was ensured. Control premises were not aware of their participation and intervention premises were not allowed to exclude themselves from the study. For the unallocated sensitivity analyses, premises that were closed prior to receiving an audit were replaced with a premises selected randomly from a matched list of any remaining premises within that LA. Randomization was carried out by an independent statistician to conceal allocation from the trial team.

Figure 2.

Trial profile. Eligible premises were allocated randomly into control and intervention groups. The premises that were available for the intervention comprise the per‐protocol group. Three premises refused and four were false positives (premises that were closed at the time of audit but re‐opened within the time available for Environmental Health Practitioners (EHPs) to audit them). In the unallocated group, premises that were not available for the intervention were replaced from the pool of remaining unallocated premises (selected randomly from the same strata of the premises being replaced; if no premises were available in that strata then no replacement was made); all remaining premises following replacement into the intervention group were added to the control group, this was conducted so that EHPs could meet their quota. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Blinding

EHPs were aware of the intervention premises, but blinded to control premises identities. Although it is feasible that EHPs who were aware of the premises in their LA could deduce which premises were in the control group, this is moderated by the large number of premises in Wales (approximately 2725). Independent statisticians in the South East Wales Trials Unit undertook the primary and secondary analyses.

Analytical strategy

Violence in premises repeats over time, and premises are prone to closure (temporary and permanent, otherwise known as censoring). A simple time to first event ignores the recurrent nature of these data and is therefore unlikely to reveal whether an intervention effect wanes over time. As our hypotheses were both specific to the rate of failure and the nature of any change over time, an analytical approach was selected that could test for both. An Andersen–Gill model was used to analyse failure in premises during the follow‐up period 20. The intervention effect was realized as a time‐varying predictor for both initial and later follow‐up visits. Variables used to balance randomization were included in the analysis. As the randomization was stratified by LA, analyses included LA as shared frailty. Frailty assumes premises within the same LA may be subject to similar influences on their risk of failure causing the LA responses to be heterogeneous. The intervention was interacted further with e–0.03t, where t was analysis time, to assess any change over time. Primary analyses were conducted on the intention‐to‐treat groups (premises assigned to control and intervention groups, irrespective of whether or not they received the intervention) with sensitivity analyses conducted on the per protocol groups (premises that received the intervention) and the non‐randomized groups that included additional premises that were added to the control and intervention groups after randomization (Fig. 2). Further exploratory analyses considered intervention dose in the intervention group only. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 14MP.

Results

The initial analysis of police data identified 837 eligible premises and a total of 2236 violent incidents throughout the 12‐month baseline period (Table 1). Most premises were open beyond 11 p.m. and hours open past 11 p.m. were similar on Friday and Saturday evenings (0 hours: Friday = 13.3%, Saturday = 13.3%; 0.5–1 hour: Friday = 12.9%, Saturday = 12.5%; 1.5–2 hours: Friday = 27.5%, Saturday = 27.7%; 2.5–3 hours: Friday = 25.9%, Saturday = 25.4%; 3.5–4 hours: Friday = 12.1%, Saturday = 12.3%; 4.5–5 hours: Friday = 5.5%, Saturday = 5.9%; 5.5–7 hours: Friday = 2.9%, Saturday = 2.9%), although opening hours may vary throughout the year, as premises can close early if there are few or no customers. Of the 837 eligible premises capacity data were available for 144 from LA licensing records. Capacity data were included historically as a licensing condition and was determined by fire services. Deregulation allowed premises to determine their own capacity, meaning that only a subset of premises licensing data included these historical data. For these 144 premises, baseline total violence was associated with capacity (Spearman's ρ = 0.38, P < 0.01), suggesting that stratifying on baseline violence was adequate.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for premises allocated initially that remained in the intention‐to‐treat analysis and those in the per‐protocol and non‐randomized sensitivity analyses. Binary indicator variables were created and designated premises as high or low in respect of historical violence and weekend opening hours. Mean and standard deviations (SD) of raw figures are included.

| Group | Control | Intervention | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n High | Mean (SD) | n High | Mean (SD) | |

| Initial allocation | (n = 300) | (n = 300) | ||

| Violence | 85 | 2.53 (3.16) | 87 | 2.78 (4.39) |

| Opening hours | 134 | 4.26 (2.94) | 132 | 4.47 (3.05) |

| Intention‐to‐treat | (n = 208) | (n = 238) | ||

| Violence | 54 | 2.41 (3.03) | 73 | 2.93 (4.75) |

| Opening hours | 97 | 4.35 (2.86) | 109 | 4.49 (2.86) |

| Per‐protocol | (n = 208) | (n = 245) | ||

| Violence | 54 | 2.41 (3.03) | 72 | 2.92 (4.75) |

| Opening hours | 97 | 4.35 (2.86) | 106 | 4.47 (2.86) |

| Non‐randomized | (n = 321) | (n = 285) | ||

| Violence | 103 | 2.64 (4.31) | 73 | 2.78 (4.46) |

| Opening hours | 172 | 4.32 (2.75) | 109 | 4.34 (2.80) |

For the initial audit, there were three refusals following EHPs’ letter of introduction, and these premises were not audited (one premises name was identical to the village in which they were situated and thus it was not possible to disambiguate the exact location of the incident in police data, another premises had recently been reviewed for licensing violations, and EHPs indicated that they did not wish to audit a third premises). There were four premises that were closed at the time of audit but re‐opened within the time available for EHPs to audit them and were audited (false negatives). All remaining premises unavailable to the study were no longer trading (as indicated in business rate data).

All available intervention premises were eligible for auditing from 1 January 2013, 25% were audited by 11 February, 50% by 25 February and 100% by 29 April.

From 1 January 2013 onwards, a total 1829 incidents were observed in the automatically curated data (1762 in the manually curated data). For the intention‐to‐treat group, overall there were 891 failures with an average 1.19 [standard deviation (SD) = 0.70] violent incidents per failure. Few premises received a second follow‐up audit (n = 16, although 97 premises scored greater than three on one or more RCIs indicating that 81 more premises should have received a follow‐up visit); for those that did there were 17 failures, representing 19 incidents (average violence per failure = 1.12, SD = 0.49) and for premises receiving an audit but no follow‐up there were 512 failures, representing 620 violent incidents (average violence per failure = 1.21, SD = 0.72). Ten control premises closed before the follow‐up period ended; these sessions were marked as missing in the data, yielding an average follow‐up period of 447.48 days (SD = 43.38) (min 76, max 455); the intervention group follow‐up average was 449.78 sessions (SD = 32.61; min 162, max 455).

Referring to Fig. 1, of the 245 intervention premises 24 premises received no feedback and presumably had no evident risks and 200 premises received verbal or written and verbal feedback. Of the remaining 21 premises, five received a follow‐up audit but no formal notice, one received a formal notice and a follow‐up audit and 15 received a follow‐up audit and no notice. EHPs could also refer premises to partner agencies. There were no referrals to the police, seven premises were referred to the fire services and 22 were referred to LA licensing. Reasons for referral to LA licensing were for premises not operating according to their licensing conditions. Reasons for formal notices covered lack of safety policies and records (n = 3), inadequate staff training (n = 1), poor condition of the premises (n = 2), poor lighting (n = 1) and significant failing in respect of gas safety (n = 1). One premises received a prohibition notice for inadequate fire safety but also demonstrated failings with regard to CCTV and staff training.

Comparison of the rate of failure in intervention and control premises

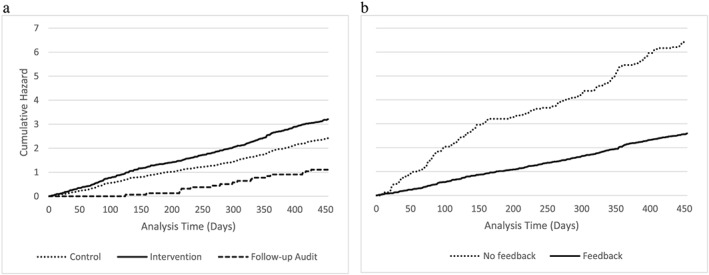

Primary analyses indicated that the intervention was associated with an increase in the rate of failure and therefore police‐recorded violence (Table 2, Fig. 3a) for the intervention group compared to the control group, a result replicated in sensitivity analyses across both automatically extracted and manually extracted data and with the per‐protocol and non‐randomized groups. For all analyses the likelihood test for LA heterogeneity (θ = 0) yielded a robust result (chibar2 > 150 for each test), justifying the inclusion of shared frailty by LA. All models performed significantly better than the null (χ2 > 470 for each model). Baseline characteristics were associated significantly with violence and higher historical levels of violence and longer opening hours were associated positively with failure in the follow‐up period.

Table 2.

Results of primary (intention‐to‐treat) analysis and sensitivity analyses (per‐protocol and non‐randomized) for both automatically extracted and manually curated data sets.

| Group | Data set | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Automated | Manual | |||

| Intention‐to‐treat | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI |

| Intervention | 1.34*** | 1.20 1.51 | 1.23** | 1.07 1.41 |

| Violence group (1 = high) | 2.55*** | 2.21 2.94 | 3.45*** | 3.00 4.01 |

| Opening hours group (1 = high) | 2.52*** | 2.22 2.85 | 2.00*** | 1.69 2.37 |

| Per‐protocol | ||||

| Intervention | 1.35*** | 1.20 1.52 | 1.24** | 1.07 1.42 |

| Violence group (1 = high) | 2.54*** | 2.24 2.88 | 3.49*** | 3.00 4.07 |

| Opening hours group (1 = high) | 2.51*** | 2.17 2.89 | 1.96*** | 1.65 2.32 |

| Non‐randomized | ||||

| Intervention | 1.33*** | 1.20 1.48 | 1.15* | 1.02 1.29 |

| Violence group (1 = high) | 2.78*** | 2.48 3.12 | 3.74*** | 3.28 2.47 |

| Opening hours group (1 = high) | 2.44*** | 2.15 2.77 | 2.13*** | 1.84 2.47 |

HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.0001.

Figure 3.

Nelson Aalen cumulative hazard estimate. (a) For control premises against all intervention premises and intervention premises receiving a follow‐up enforcement visit. (b) Intervention premises only, for those premises receiving feedback (written and verbal) and those receiving no feedback

Analysis of change in the rate of violence over time during the follow‐up period

Analyses examined whether the intervention effect waned during the follow‐up period; however, no significant interaction with time was noted.

The effect of intervention dose on outcomes

Additional unplanned exploratory analyses considered the effect of follow‐up visits (n = 16 premises received a follow‐up visit) on failure (Fig. 3a) against the control group and, for the intervention group alone, whether or not receiving EHP feedback effected failure (Fig. 3b). The net hazard ratio (HR) for the effect of a follow‐up audit was determined through multiplying the audit HR (Table 2) with the follow‐up audit HR (HR = 0.46, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.26 0.71, P < 0.01; HR = 0.57), suggesting premises that received a follow‐up audit experienced fewer failures. To explore further the effect of the intervention on failure, intervention premises were divided into two groups according to the nature of the feedback given: premises that received no advice and premises that received feedback. For the intention‐to‐treat group, using the automated data and controlling for violence and opening‐hours groups, premises receiving feedback (n = 217) yielded a lower hazard rate compared to those that did not (n = 21; HR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.42 to 0.63, P < 0.001) and controlling for baseline violence and opening hours. These secondary analyses are problematic, however, given the low number of premises and that the effects might be attributable to regression to the mean.

Discussion

Our findings show that, compared to usual practice, the SMILE intervention was associated with a sustained increase in police recorded violence. The large number of premises that closed before the intervention was delivered, probably attributable to the economic recession at that time, meant that a lower sample size than target was achieved and the trial was underpowered. Furthermore, the methodological approach assumed a continuous process (premises operational over time) that may or may not produce violence but only from randomization onwards. Studies adopting similar methods may benefit from including pre‐randomization outcome data and modelling the effect of the intervention as a time‐varying covariate. This may identify where underlying trends emerge, whether they are due to the intervention or preceded the intervention.

The collaborative approach to the intervention aided the successful adoption, development and implementation of SMILE within EHP working practices, resulting in high levels of premises reach and the successful completion of a robust randomized controlled trial in a complex area of study. However, data presented here and confirmed in an embedded process evaluation highlight implementation failure of a key intervention mechanism of action: the expected follow‐up enforcement visits were not delivered by EHPs 11. This raises questions about EHPs confidence in this new area of work. Future delivery of statutory interventions may require partnership working with more experienced partners, such as licensing officers, to overcome EHP resistance 11, 13. The earlier feasibility study that informed the current trial 10 was not conducted by EHPs, but a private organization that was not partnered with the police and licensing. In this feasibility study all intervention premises received a follow‐up audit. While EHPs overcame the barrier involved with recruiting premises it also brought about failures elsewhere.

The study would have benefited from more objective measures of violence, such as those available in hospital unscheduled care data. Police‐recorded violence only include offences that have been reported to or observed by them, and therefore underestimate levels due to difficulties in ascertainment, which result from fear of reprisals, poor attitudes towards police involvement and an unwillingness to have conduct scrutinized 21. Therefore, a potential explanation of this study's results is that EHP scrutiny increased the ascertainment of violence by the police, as has happened elsewhere 22.

Violence is a burden on individuals and health services. This trial demonstrates that EHPs are able to identify risks, willing to work with premises and submit to robust evaluation methods. However, work in this new context, together with revised working practices for EHPs, which emphasizes a lighter approach to regulation 14, 17, blunted the opportunity to enforce change. EHPs have a public health remit and could still play an important role in assisting health services such as the NHS to discharge their responsibilities to address proactively the causes of violence.

Trial registration

This trial was registered at the UK Clinical Research Network Study Portfolio (www.ukctg.nihr.ac.uk) (14077) and the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number Register (www.isrctn.com) (78924818).

Declaration of interests

None.

Supporting information

Appendix S1 The risk audit developed for use in the Safety Management in the Licensed Environment (SMILE) intervention. Descriptive statistics for all premises audited are presented in Supporting information, Appendix S2.

Appendix S2 Descriptive statistics.

Acknowledgements

The trial is funded by the National Institute of Health Research Public Health Research (NIHR PHR) Programme (project number 10/3010/21). The funder had no role in study design, data analysis, data interpretation, data collection or writing of the paper. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. This paper is independent research commissioned by the National Institute of Health Research. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR PHR Programme or the Department of Health. The work was undertaken with the support of The Centre for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions for Public Health Improvement (DECIPHer), a UKCRC Public Health Research Centre of Excellence. Joint funding (MR/KO232331/1) from the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Economic and Social Research Council, Medical Research Council, the Welsh Government and the Wellcome Trust, under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration, is gratefully acknowledged. Thanks are due to Claire Simpson and Helen Stanton for administrative work on the project. We would also like to thank the Senior EHPs (Richard Henderson, Sarah Jones, Iwan Llewellyn, Simon Morse, Liz Vann, and Gweirydd Williams) for their help during the development stage of the trial and their useful comments and suggestions throughout, and also to all EHPs who delivered the intervention to licensed premises in Wales. Study protocol can be retrieved from www.biomedcentral.com/1471‐2458/14/21 and http://orca.cf.ac.uk/56949/. The protocol was published before data collection had ended. The authors confirm that (a) the material has not been published in whole or in part elsewhere; (b) the manuscript is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere; (c) all authors have been personally and actively involved in substantive work leading to the report, and will hold themselves jointly and individually responsible for its content; (d) all relevant ethical safeguards have been met in relation to subject protection and has been reviewed by an appropriate ethical review committee. The research complies with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Moore, S. C. , Alam, M. F. , Heikkinen, M. , Hood, K. , Huang, C. , Moore, L. , Murphy, S. , Playle, R. , Shepherd, J. , Shovelton, C. , Sivarajasingam, V. , and Williams, A. (2017) The effectiveness of an intervention to reduce alcohol‐related violence in premises licensed for the sale and on‐site consumption of alcohol: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction, 112: 1898–1906. doi: 10.1111/add.13878.

References

- 1. Moore S. C., Brennan I., Murphy S. Predicting and measuring premises‐level harm in the night‐time economy. Alcohol Alcohol 2011; 46: 357–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Graham K., Homel R. Raising the Bar: Preventing Aggression In and Around Bars, Pubs and Clubs. Cullompton: Willan Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Alcohol 2004. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. Available at: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_status_report_2004_overview.pdf (accessed 16 May 2017) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6mDHTAjvF). [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sivarajasingam V., Moore S. C., Page N., Shepherd J. P. Violence in England and Wales in 2014: An Accident and Emergency Perspective. Cardiff: Cardiff University; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hoskins R., Benger J. What is the burden of alcohol‐related injuries in an inner city emergency department? Emerg Med J 2013; 30: e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Walker A., Flatley J., Kershaw C., Moon D. Crime in England and Wales 2008/09. London: Home Office; 2009. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/crime-in-england-and-wales-2009-to-2010-findings-from-the-british-crime-survey-and-police-recorded-crime (accessed 16 May 2017) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6mDHNHAJI). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tindall J., Groombridge D., Wiggers J., Gillham K., Palmer D., Clinton‐McHarg T. et al. Alcohol‐related crime in city entertainment precincts: public perception and experience of alcohol‐related crime and support for strategies to reduce such crime. Drug Alcohol Rev 2016; 35: 263–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brennan I., Moore S. C., Byrne E., Murphy S. Interventions for disorder and severe intoxication in and around licensed premises, 1989–2009. Addiction 2011; 106: 706–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ker K., Chinnock P. Interventions in the alcohol server setting for preventing injuries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; Issue 2 Art. No.: CD005244 https://doi.org/ 10.1002/14651858.CD005244.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moore S. C., Brennan I., Murphy S., Byrne E., Moore S., Shepherd J. et al. The reduction of intoxication and disorder in premises licensed to serve alcohol: an exploratory randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2010; 10: 607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Williams A., Moore S. C., Shovelton C., Moore L., Murphy S. An all‐Wales licensed premises intervention: a process evaluation of an environmental health intervention to reduce alcohol related violence in licensed premises. BMC Public Health 2016; 16: 455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Campbell M. K., Piaggio G., Elbourne D. R., Altman D. G. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 2012; 345: e5661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moore S. C., O'Brien C., Alam M. F., Cohen D., Hood K., Huang C. et al. All‐Wales licensed premises intervention (AWLPI): a randomised controlled trial to reduce alcohol‐related violence. BMC Public Health 2014; 14: 21–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kidney D. Environmental Health: a New Relationship for Regulators. London: Chartered Institute of Environmental Health; 2011. Available at: http://www.cieh.org/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=37640 (accessed 16 May 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rebellon C. J., Barnes J. C., Agnew R. A unified theory of crime and delinquency: foundation for biosocial criminology In: DeLisi M., Vaughn M. G., editors. The Routledge International Handbook of Biosocial Criminology. London: Routledge; 2015, pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Innes M. Understanding Social Control: Deviance, Crime and Social Order. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Regulators’ Code . Department for business innovation and skills, better regulation delivery office; 2014. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/regulators-code (accessed 16 May 2017) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6mDHiHH5o).

- 18. Moore S. C., Murphy S., Moore S. N., Brennan I., Byrne E., Shepherd J. P. et al. An exploratory randomised controlled trial of a premises‐level intervention to reduce alcohol‐related harm including violence in the United Kingdom. BMC Public Health 2012; 12: 412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carter B., Hood K. Balance algorithm for cluster randomized trials. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008; 8: 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cook R. J., Lawless J. F. The Statistical Analysis of Recurrent Events. New York: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Clarkson C., Cretney A., Davis G., Shepherd J. Assaults: the relationship between seriousness, criminalisation and punishment. Crim Law Rev 1994; 4: 4–20. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Burns L., Coumarelos C. Policing Pubs: Evaluation of a Licensing Enforcement Strategy. Sydney: New South Wales Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research; 1993. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1 The risk audit developed for use in the Safety Management in the Licensed Environment (SMILE) intervention. Descriptive statistics for all premises audited are presented in Supporting information, Appendix S2.

Appendix S2 Descriptive statistics.