Abstract

There are limited data on the safety and efficacy of switching to secukinumab from cyclosporine A (CyA) in patients with psoriasis. The purpose of the present study was to assess the efficacy and safety of secukinumab for 16 weeks after direct switching from CyA in patients with moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis. In this multicenter, open‐label, phase IV study, 34 patients with moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis and inadequate response to CyA received secukinumab 300 mg s.c. at baseline and weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, 8 and 12. The primary end‐point was ≥75% improvement from baseline in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score (PASI 75) at week 16. The efficacy of secukinumab treatment was evaluated up to week 16, and adverse events (AE) were monitored during the study. The primary end‐point of the PASI 75 response at week 16 was achieved by 82.4% (n = 28) of patients receiving secukinumab. Early improvements were observed with secukinumab, with PASI 50 response of 41.2% at week 2 and PASI 75 response of 44.1% at week 4. AE were observed in 70.6% (n = 24) of patients, and there were no serious AE or deaths reported in the entire study period. Secukinumab showed a favorable safety profile consistent with previous data with no new or unexpected safety signals. The results of the present study show that secukinumab is effective in patients with psoriasis enabling a smooth and safe direct switch from CyA to biological therapy.

Keywords: cyclosporine A, interleukin‐17A, psoriasis, secukinumab, switch

Introduction

Plaque psoriasis is a chronic, inflammatory, depressing skin disorder, which is associated with a period of recurrence and a reduced quality of life.1, 2 The majority of patients with psoriasis are treated with traditional systemic therapies before prescribing biologics. Cyclosporine A (CyA), an immunosuppressive drug that modulates the activity of T lymphocytes and other immune cells, is a common systemic therapy for plaque psoriasis.3 In cases with inadequate responses or adverse reactions, CyA should be discontinued. Currently, there is limited evidence on the methods of transitioning from conventional systemic therapy, such as CyA, to biological therapy, either directly or with an overlap. When CyA is abruptly stopped and directly switched, psoriasis symptoms often worsen because the introduction of biological treatment does not rapidly compensate for the effect of CyA.4 An international consensus report as well as the USA, Europe, and Japan guidelines describe that a short overlap period (e.g. 2–8 weeks) between CyA and biological therapy can be considered in order to reduce the risk of relapse.5, 6, 7, 8, 9 However, co‐administration of CyA and biologics is not recommended because of undesirable immune suppression.6

It has been reported that interleukin‐17A (IL‐17A), a pro‐inflammatory cytokine secreted mainly by T helper 17 cells, plays an important role in disease progression and maintenance of psoriasis.10 Secukinumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody that selectively neutralizes IL‐17A, has been shown to have a significant efficacy in the treatment of moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis11, 12, 13, 14 and psoriatic arthritis,15, 16, 17 showing a rapid onset of action and sustained responses with a favorable safety profile. Secukinumab has been approved for the treatment of multiple indications, such as moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis in USA and Europe.15, 17, 18 In Japan, it is approved for plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and generalized pustular psoriasis.19 The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of secukinumab after immediate withdrawal of CyA. Our hypothesis was that because of the rapid mode of action of secukinumab, it could compensate for the abrupt discontinuation of CyA providing a safe and effective alternative for patients with psoriasis who require a switch from CyA.

Methods

Study design

The present phase IV, multicenter, single‐arm, open‐label study assessed the efficacy and safety of secukinumab for 16 weeks after direct switching from CyA. The study was carried out at 11 sites in Japan between June 2015 and May 2016, and included three periods: (i) screening period (up to 4 weeks); (ii) induction period (4 weeks); and (iii) maintenance period (12 weeks). Eligible patients who had an inadequate response to CyA ceased the treatment 1 day before the baseline visit, and then received subcutaneous (s.c.) secukinumab 300 mg using pre‐filled syringes at baseline, and weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, 8 and 12, in alignment with the approved label.

Patients

Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years and diagnosed with plaque psoriasis at least 6 months before baseline. Patients had to be taking CyA for at least 12 weeks before baseline, and should have experienced a primary or secondary inadequate response to the treatment, as defined by the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score ≥10 and Investigator's Global Assessment modified (IGA mod) 2011 score ≥2 at baseline. The key exclusion criteria were forms of psoriasis other than chronic plaque, ongoing use of prohibited treatments, previous exposure to secukinumab or any other biological drug directly targeting IL‐17A or the IL‐17 receptor, or discontinuation of CyA treatment because of its side effects, such as renal impairment and hypertension at screening.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of each participating site, and the study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Eligible patients provided written informed consent.

Outcomes

The primary end‐point was the proportion of patients achieving a ≥75% improvement from baseline in the PASI score (PASI 75) response at week 16. Secondary efficacy end‐points included reduction in the PASI score compared with baseline at week 4, PASI 50 and PASI 75 responses at week 4, PASI 90, IGA 0 or 1 response, percentage change from baseline in Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) score and proportion of patients achieving a DLQI response of 0 or 1 at week 16. The safety and tolerability of secukinumab after abrupt withdrawal of CyA was also evaluated as a secondary end‐point. Adverse events (AE) were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities terminology.

Exploratory analyses included evaluation of the PASI 100 response at week 16, and PASI 50/75/90 response rates in subgroups according to previous systemic therapy and extent of exposure to CyA, either by the time after the first use of CyA (including the intermittent treatment period) or by the CyA dose of the regimen used the longest during 24 weeks before baseline.

Statistical analysis

Approximately 30 patients entered into the induction period, as the sample size provided the expected lower limit of the 95% confidence interval for the PASI 75 response rate to be 59.5%, which is substantially higher compared with the response rate of 5% for the placebo group observed in secukinumab phase III trials. The response rates with the 95% confidence intervals of the efficacy variables were assessed in the full analysis set. The full analysis set comprised all patients who entered the induction period. Missing values with respect to response variables based on PASI and IGA mod 2011 scores were imputed as a non‐response (non‐responder imputation). For DLQI results, missing values were replaced using a last observation carried forward approach; baseline values were not carried forward. Safety analyses were carried out on the safety set including all patients who received at least one dose of the study drug during the treatment period.

Results

Patients

Of 37 Japanese patients screened, 34 patients were enrolled in the present study, and all patients completed the required 16 weeks of treatment. The mean time since diagnosis of psoriasis was 18.6 years, and the mean PASI score at baseline was 15.1 (Table 1). Of the 34 patients, six were previously treated and failed with biological systemic therapies (ustekinumab, n = 3; infliximab, n = 1; adalimumab, n = 1; and CNTO1959 [an anti‐IL‐23 monoclonal antibody], n = 1). The trend of the psoriasis condition from 3 months before baseline was mostly “no change” (61.8%) or “worsening” (32.4%), with just two patients showing an “improving” (5.9%) trend. The time since the first use of CyA was >5 years in 41.2% of patients, and the mean daily exposure to CyA (with the regimen that was used longest) during 24 weeks before baseline was 121.32 mg.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics

| Demographic variable | Secukinumab n = 34 |

|---|---|

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 51.50 ± 12.08 |

| Male, n (%) | 24 (70.6) |

| Ethnicity: Japanese, n (%) | 34 (100.0) |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 24.25 ± 3.89 |

| Weight, kg (mean ± SD) | 67.27 ± 13.36 |

| Baseline PASI score (mean ± SD) | 15.05 ± 3.48 |

| Baseline IGA mod 2011 score, n (%) | |

| 2 Mild disease | 5 (14.7) |

| 3 Moderate disease | 24 (70.6) |

| 4 Severe disease | 5 (14.7) |

| Time since first diagnosis of psoriasis therapy, years (mean ± SD) | 18.64 ± 11.22 |

| Systemic psoriasis therapy except CyA, n (%) | 25 (73.5) |

| Failure to systemic psoriasis therapy | 23 (92.0) |

| Biologic systemic psoriasis therapy, n (%) | 6 (17.6) |

| Failure to biologic systemic psoriasis therapy | 6 (100.0) |

| Change in psoriasis condition, n (%) | |

| Improving | 2 (5.9) |

| No change | 21 (61.8) |

| Worsening | 11 (32.4) |

| Duration after the first use of CyA, n (%) | |

| ≤6 months | 1 (2.9) |

| >6 months–1 year | 3 (8.8) |

| >1 year–2 years | 7 (20.6) |

| >2 years–5 years | 9 (26.5) |

| >5 years | 14 (41.2) |

| Duration after the first use of CyA (days) | |

| Mean ± SD | 2061.1 ± 2236.97 |

| Min–max | 133–9457 |

| Exposure to CyA (mg/day) used longest from 24 weeks before baseline | |

| Mean ± SD | 121.32 ± 54.78 |

| Min–max | 28.6–250.0 |

BMI, body mass index; CyA, cyclosporine; IGA, Investigator's Global Assessment; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; SD, standard deviation.

Efficacy

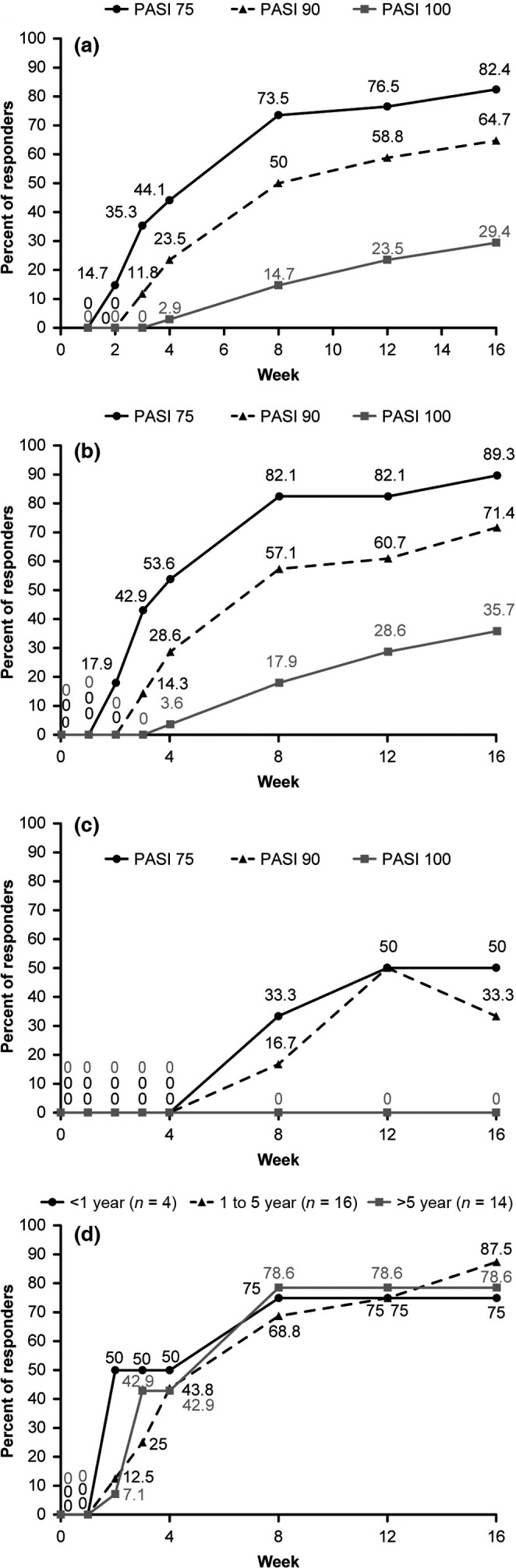

The primary end‐point of PASI 75 response at week 16 was achieved by 82.4% (n = 28) of patients receiving secukinumab (Fig. 1a). PASI 90, PASI 100, and IGA0/1 responses were achieved by 64.7% (n = 22), 29.4% (n = 10), and 70.6% (n = 24) of the patients, respectively, at week 16 (Fig. 1a, Fig. S1). Early improvements were also observed after the treatment with PASI 50 response achieved in 41.2% (n = 14) of the patients at week 2 (Fig. 2, Fig. S2). The mean percentage change from baseline in PASI score at week 4 was ‐65.6% (Fig. S3), and PASI 50 and PASI 75 responses were achieved by 76.5% (n = 26) and 44.1% (n = 15) of patients, respectively, at week 4.

Figure 1.

Proportion of patients with clinical responses through week 16. (a) Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 75, PASI 90 and PASI 100 responses in the overall population. (b) PASI 75, PASI 90 and PASI 100 responses in biologic therapy naïve patients. (c) PASI 75, PASI 90 and PASI 100 responses in patients with previous exposure to biological therapy. (d) The proportion of patients with PASI 75 response; in the subgroups by duration after the first use of cyclosporine A (CyA). Data from full analysis set. PASI response was calculated from baseline (the day of switching from CyA); missing data were imputed as non‐responses.

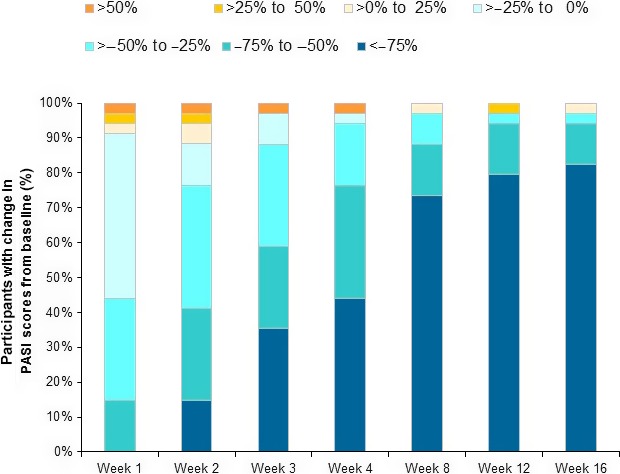

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients with change in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scores from baseline. Data from full analysis set.

Although four patients (11.8%) experienced an increase in the PASI score from baseline at week 2, an improvement was observed from week 3 in three of these four patients. In one patient (2.9%), symptoms worsened with >50% increase in the PASI score, and no improvement was observed until week 16 (Fig. 2).

Higher response rates were observed in biological therapy‐naïve patients compared with those who were exposed to biological therapy previously, with 89.3% and 71.4% response rates for PASI 75 and PASI 90 responses, respectively, in the biological therapy‐naïve patients at week 16 (Fig. 1b). Improvement in clinical symptoms was also observed in patients with previous exposure to biological therapy, with PASI 75 and PASI 90 responses achieved by half and one‐third of the patients, respectively, at week 16 (Fig. 1c).

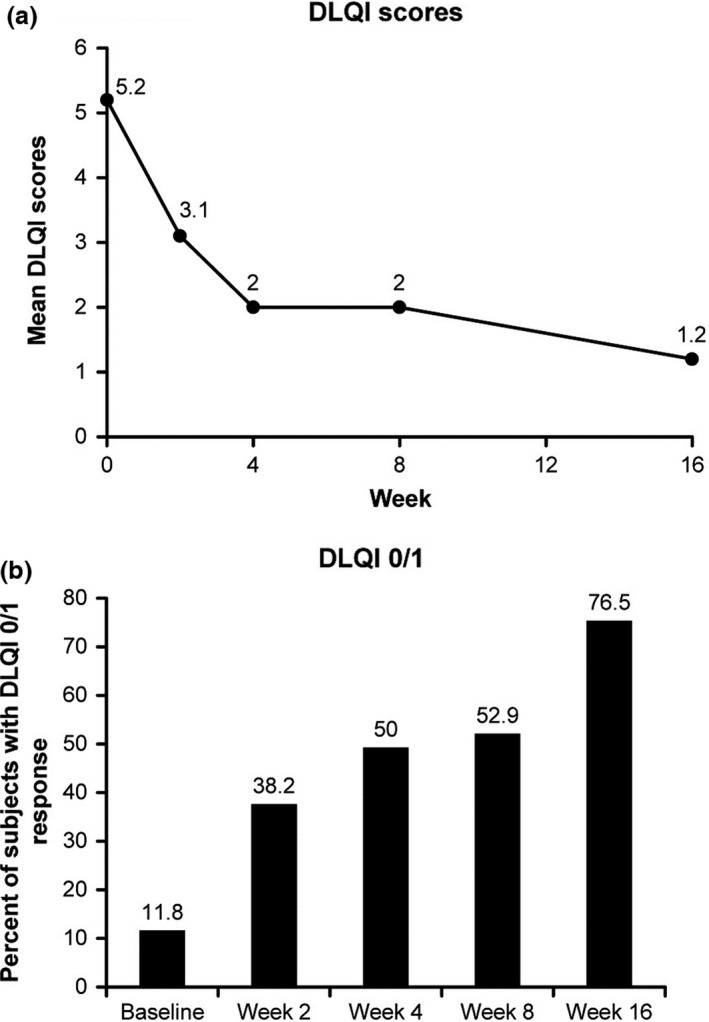

The mean DLQI score, which was 5.2 at baseline, reduced to 1.2 at week 16 (Fig. 3a). The proportion of patients with a DLQI response of 0 or 1 was increased from 11.8% at baseline to 76.5% at week 16 (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

(a) Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores through week 16 and (b) the proportion of patients with a response of DLQI 0/1 by visit. Data from full analysis set.

The effects of exposure to CyA on secukinumab treatment response were assessed by comparing the PASI response among the subgroups with different durations after the first use of CyA (Fig. 1d), and among the subgroups with different CyA doses before baseline (Fig. S4). Similar improvements in symptoms were observed across the subgroups of different durations of CyA use (PASI 75 response of 75.0%, 87.5%, and 78.6% for <1 year, 1–5 years, and >5 years, respectively, at week 16) or different doses (PASI 75 response of 81.8%, 88.9%, 75.0%, and 83.3% for <1.5 mg/kg, 1.5–2.0 mg/kg, 2.0–2.5 mg/kg, and ≥2.5 mg/kg, respectively, at week 16).

Safety

Compared with the pooled phase III secukinumab safety data,20 the present study showed no new or unexpected safety signals. AE were reported in 70.6% (n = 24) of patients, and there were no serious AE or deaths reported during the entire study period (Table 2). One serious AE (angina pectoris) was observed after completion of the study (day 118); however, the investigator did not suspect it to be related to secukinumab treatment. The most common treatment‐emergent AE, by preferred term, were nasopharyngitis (n = 7), dermatitis contact (n = 2), hypertension (n = 2) and rash (n = 2). No cases of candidiasis, neutropenia, inflammatory bowel disease or tuberculosis were reported.

Table 2.

Adverse events during the 16‐week period

| Variable | Secukinumab n = 34 n (%) |

|---|---|

| Patients with any AE | 24 (70.6) |

| Patients with serious or other significant events | |

| Death | 0 (0.0) |

| Non‐fatal SAE | 0 (0.0) |

| Discontinued study treatment due to any AE | 0 (0.0) |

| Most common AEa | |

| Nasopharyngitis | 7 (20.6) |

| Dermatitis contact | 2 (5.9) |

| Hypertension | 2 (5.9) |

| Rash | 2 (5.9) |

Common adverse events (AE) are expressed by the preferred term and are those that occurred in more than one patient during the 16‐week treatment period. SAE, serious adverse event.

Discussion

There are a number of circumstances when switching from a conventional therapy to biologics can be appropriate; for example, in the case of loss of efficacy or appearance of toxicity or intolerance of the conventional therapy.9 Among available transitioning biological therapies, infliximab has the greatest efficacy and the fastest onset of action, followed by ustekinumab, adalimumab and etanercept.21, 22, 23 It has been reported that, in cases when CyA is directly switched to a biological therapy with a slow onset of clinical response (e.g. etanercept), psoriasis flare might occur.24 However, when CyA was abruptly switched to infliximab, PASI scores decreased without worsening of psoriasis,4 suggesting that biologics with a rapid response do not require co‐administration of CyA for a smooth transition. Accumulating evidence has shown that new anti‐IL‐17A therapies offer a more reliable response with an improved efficacy.10 Furthermore, a recent study investigating the mechanism of relapse induced by CyA withdrawal showed that production of IL‐17A was increased after discontinuation of CyA in the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice and the severity of relapse was reduced by treatment with anti‐IL‐17A antibody, suggesting that a burst of IL‐17A production is at least partially responsible for the relapse.25 This evidence suggest that a rapidly acting anti–IL‐17A therapy might show quick improvement in symptoms without relapse after a direct switch from CyA.

We hypothesized that the rapid mode of secukinumab's action could quickly compensate for CyA, providing a safe and effective transition, and thus we carried out this first prospective study to assess the efficacy of secukinumab after an abrupt discontinuation of CyA. The results showed that secukinumab enables a smooth and direct switch from CyA in patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis without relapse of symptoms. The primary end‐point of PASI 75 at week 16 was achieved by 82.4% of patients receiving secukinumab. This response rate was highly comparable with the results of a previous pivotal phase III study (ERASURE),12 in which the PASI 75 response with secukinumab 300 mg in Japanese patients was 82.8% at week 16.26 More stringent treatment goals of PASI 90 and PASI 100 responses were achieved by 64.7% and 29.4% of patients, respectively, at week 16. Furthermore, the DLQI total score was greatly reduced from baseline with the proportion of patients achieving a DLQI response of 0 or 1 (indicating no impairment of patient's quality of life as a result of skin problems) reaching 76.5% at week 16.

One of the major objectives of the present study was the evaluation of the short‐term response after the switch to secukinumab, as relapse was often observed in the cases of switching to other biological therapies.24 Early improvements in clinical responses were observed, with 41.2% of patients achieving the PASI 50 response at week 2. An improvement was seen in all clinical responses at week 4, with PASI 75 response achieved by 44.1% of patients at week 4. The DLQI score dropped at week 2, and the proportion of patients with a DLQI response of 0 or 1 increased to 38.2% at week 2 from 11.8% at baseline. These results suggest that the direct switch to secukinumab enables a rapid improvement in psoriasis symptoms in a majority of patients.

Similar to previous clinical studies in patients with psoriasis, response rates were higher in biological therapy‐naïve patients. However, a notable improvement in symptoms was also observed in patients with a history of previous exposure or inadequate response to biological therapy.

Of the 34 enrolled patients, only one (2.9%) did not achieve a decrease in the PASI score during the 16‐week treatment period compared with baseline (11.2), with the highest score of 36.8 at week 2 and 12.8 at week 16. This male patient was a 75‐year‐old non‐smoker with a disease duration of 22 years, and had received the first prescription of CyA at the time of diagnosis. This patient had failed previous ustekinumab therapy, and reinitiated CyA treatment with a daily exposure of 150 mg/day over 24 weeks up to the start of the current study. Notably, this patient had various comorbidities, such as hypertension, hyperuricemia, dyslipidemia and renal impairment, and experienced angina pectoris after completion of the 16‐week study treatment. As accumulating evidence has shown the association of psoriasis with metabolic and cardiovascular diseases, simultaneous treatments of psoriasis and comorbid diseases with appropriate medications can be essential to achieve a better control of psoriasis.

There was no reported study evaluating the possible relationship between the clinical response to switching to biological therapy and the extent of exposure to CyA. In the current study, CyA was used for many years by a majority of the patients, and the CyA dose varied from the minimum daily dose of <50 mg/day (2 days/week) to the maximum of 250 mg/day, suggesting that patients can tolerate CyA for years with a flexible CyA regimen. Nevertheless, CyA was apparently inadequate to control the symptoms in those patients. Treatment with secukinumab showed efficacy in the majority of the patients, irrespective of the duration and dosage of the previous treatment with CyA, indicating that regardless of the extent of exposure to CyA, secukinumab rapidly improves psoriasis symptoms after the switch.

A direct switch is a transition method that avoids excessive immune suppression, which is a common safety concern in the case of switch with an overlap period. In agreement with the concept, the present direct switch study showed no new or unexpected safety signals during the 16‐week treatment, with a safety profile consistent with that reported in the pivotal secukinumab phase III trials.12, 14, 16, 17 It is noteworthy that the incidence of AE during the 4‐week induction period was lower (29.4%) than that of the 16‐week entire study period (70.6%), suggesting a smooth switch to secukinumab without major safety concerns.

We selected an open‐label, single‐arm design, because the use of a placebo or control arm with switching after washout was not ethical considering the severity of psoriasis disease and probable flare during the washout period in the patients who had an inadequate response to CyA. The study design (without control/comparator group) resembled a previous open‐label, uncontrolled study, wherein the abrupt switch from CyA to infliximab resulted in a marked reduction in PASI scores without worsening of psoriasis.4 Additionally, the current study did not compare between direct switch from CyA and co‐administration with CyA tapering, because the co‐administration of CyA and biologics was generally not a recommended transition method because of undesirable immune suppression.6

One limitation of the present study was that patients who showed side‐effects as a result of CyA treatment at screening were excluded from the study. Thus, the results of the present study are not applicable to those cases in which CyA needs to be discontinued due to the appearance of side‐effects/safety issues.

In conclusion, the direct switch from CyA to secukinumab led to an early improvement in psoriasis symptoms without a CyA withdrawal‐associated relapse in the majority of patients. Treatment with secukinumab, initiated immediately after discontinuing CyA, was well tolerated without unexpected safety signals. These results supported our hypothesis indicating that secukinumab is effective with fast onset of action in patients with plaque psoriasis, and serves as a potential biological therapy enabling a smooth and safe transition from CyA. This is the first study reporting a successful direct switch from CyA to anti‐IL‐17A therapy, which guides the treatment transition in real‐world clinical practice.

Conflict of Interest

H. F., A. F., M. Y., R. T., and Y. Tani are employees of Novartis. M. O., A. M., A. I., S. I., and Y. Tada received research grants and/or honorariums from Novartis and/or Maruho. H. N. received honorariums from Maruho. M. O., A. M., S. I., and H. N. received consultancy fee from Novartis.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Proportion of patients with Investigator's Global Assessment modified 2011 0 or 1 response through week 16 in the overall population.

Figure S2. Proportion of patients with Psoriasis Area and Severity Index 50 response through week 16 in the overall population.

Figure S3. The mean percentage change from baseline in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index through week 16 in the overall population.

Figure S4. The proportion of patients with Psoriasis Area and Severity Index 75 response: In the subgroups by cyclosporine A dose used longest during 24 weeks before baseline.

Acknowledgments

The following principle investigators are acknowledged for their support in the trial: Dr Mamitaro Ohtsuki from Jichi Medical University Hospital, Tochigi, Japan; Dr Atsuyuki Igarashi from NTT Medical Center Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan; Dr Hideshi Torii from Japan Community Health Care Organization Tokyo Yamate Medical Center, Tokyo, Japan; Dr Akimichi Morita from Nagoya City University Hospital, Aichi, Japan; Dr Shinichi Imafuku from Fukuoka University Hospital, Fukuoka, Japan; Dr Mari Higashiyama from Nissay Hospital, Osaka, Japan; Dr Tadashi Terui from Nihon University Itabashi Hospital, Tokyo, Japan; Dr Takafumi Etoh from Tokyo Teishin Hospital, Tokyo, Japan; Dr Tomotaka Mabuchi from Tokai University Hospital, Kanagawa, Japan; Dr Yayoi Tada from Teikyo University Hospital, Tokyo, Japan; and Dr Yoshinori Umezawa from The Jikei University Hospital, Tokyo, Japan. The authors thank Nori Mamiya (Novartis Pharma KK) and Vasundhara Pathak (Novartis Healthcare Private Limited) for providing medical writing assistance. The sponsor (Novartis) performed the statistical analysis, and Dr Ohtsuki takes responsibility for the accuracy of the results. All authors reviewed and provided feedback on subsequent versions and agreed on the final version and to submit the manuscript for publication. Novartis Pharma KK and Maruho Co., Ltd. funded the present study.

References

- 1. Menter A. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis overview. Am J Manag Care 2016; 22: s216–s224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ograczyk A, Miniszewska J, Kepska A, Zalewska‐Janowska A. Itch, disease coping strategies and quality of life in psoriasis patients. Postepy Dermatol Alergol 2014; 31: 299–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Maza A, Montaudie H, Sbidian E et al Oral cyclosporin in psoriasis: a systematic review on treatment modalities, risk of kidney toxicity and evidence for use in non‐plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2011; 25 (Suppl 2): 19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Torii H, Nakagawa H. Long‐term study of infliximab in Japanese patients with plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, pustular psoriasis and psoriatic erythroderma. J Dermatol 2011; 38: 321–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA et al Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 6. Guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: case‐based presentations and evidence‐based conclusions. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011; 65: 137–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ohtsuki M, Terui T, Ozawa A et al Japanese guidance for use of biologics for psoriasis (the 2013 version). J Dermatol 2013; 40: 683–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pathirana D, Ormerod AD, Saiag P et al European S3‐guidelines on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009; 23 (Suppl 2): 1–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith CH, Anstey AV, Barker JN et al British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for biologic interventions for psoriasis 2009. Br J Dermatol 2009; 161: 987–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mrowietz U, de Jong EM, Kragballe K et al A consensus report on appropriate treatment optimization and transitioning in the management of moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014; 28: 438–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gaffen SL, Jain R, Garg AV, Cua DJ. The IL‐23‐IL‐17 immune axis: from mechanisms to therapeutic testing. Nat Rev Immunol 2014; 14: 585–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hueber W, Patel DD, Dryja T et al Effects of AIN457, a fully human antibody to interleukin‐17A, on psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and uveitis. Sci Transl Med 2010; 2: 52ra72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M et al Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis–results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 326–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rich P, Sigurgeirsson B, Thaci D et al Secukinumab induction and maintenance therapy in moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase II regimen‐finding study. Br J Dermatol 2013; 168: 402–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thaci D, Humeniuk J, Frambach Y et al Secukinumab in psoriasis: randomized, controlled phase 3 trial results assessing the potential to improve treatment response in partial responders (STATURE). Br J Dermatol 2015; 173: 777–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McInnes IB, Mease PJ, Kirkham B et al Secukinumab, a human anti‐interleukin‐17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriatic arthritis (FUTURE 2): a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2015; 386: 1137–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McInnes IB, Sieper J, Braun J et al Efficacy and safety of secukinumab, a fully human anti‐interleukin‐17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with moderate‐to‐severe psoriatic arthritis: a 24‐week, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase II proof‐of‐concept trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73: 349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mease PJ, McInnes IB, Kirkham B et al Secukinumab Inhibition of Interleukin‐17A in Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1329–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Baeten D, Sieper J, Braun J et al Secukinumab, an Interleukin‐17A Inhibitor, in Ankylosing Spondylitis. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 2534–2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Imafuku S, Honma M, Okubo Y et al Efficacy and safety of secukinumab in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis: a 52‐week analysis from phase III open‐label multicenter Japanese study. J Dermatol 2016; 43: 1011–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van de Kerkhof PC, Griffiths CE, Reich K et al Secukinumab long‐term safety experience: a pooled analysis of 10 phase II and III clinical studies in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 75: 83–98. e84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nast A, Sporbeck B, Rosumeck S et al Which antipsoriatic drug has the fastest onset of action? Systematic review on the rapidity of the onset of action. J Invest Dermatol 2013; 133: 1963–1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reich K, Burden AD, Eaton JN, Hawkins NS. Efficacy of biologics in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis: a network meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Dermatol 2012; 166: 179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schmitt J, Rosumeck S, Thomaschewski G, Sporbeck B, Haufe E, Nast A. Efficacy and safety of systemic treatments for moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis: meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Dermatol 2014; 170: 274–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mrowietz U, Kragballe K, Nast A, Reich K. Strategies for improving the quality of care in psoriasis with the use of treatment goals–a report on an implementation meeting. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2011; 25 (Suppl 3): 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Saitoh K, Kon S, Nakatsuru T et al Anti‐IL‐17A blocking antibody reduces cyclosporin A‐induced relapse in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice. Biochem Biophy Rep 2016; 8: 139–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ohtsuki M, Morita A, Abe M et al Secukinumab efficacy and safety in Japanese patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis: subanalysis from ERASURE, a randomized, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 study. J Dermatol 2014; 41: 1039–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Proportion of patients with Investigator's Global Assessment modified 2011 0 or 1 response through week 16 in the overall population.

Figure S2. Proportion of patients with Psoriasis Area and Severity Index 50 response through week 16 in the overall population.

Figure S3. The mean percentage change from baseline in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index through week 16 in the overall population.

Figure S4. The proportion of patients with Psoriasis Area and Severity Index 75 response: In the subgroups by cyclosporine A dose used longest during 24 weeks before baseline.