Abstract

We describe a platform utilizing two methods based on hydrogen–deuterium exchange (HDX) coupled with mass spectrometry (MS) to characterize interactions between a protein and a small-molecule ligand. The model system is apolipoprotein E3 (apoE3) and a small-molecule drug candidate. We extended PLIMSTEX (protein–ligand interactions by mass spectrometry, titration, and H/D Exchange) to the regional level by incorporating enzymatic digestion to acquire binding information for peptides. In a single experiment, we not only identified putative binding sites, but also obtained affinities of 6.0, 6.8, and 10.6 µM for the three different regions, giving an overall binding affinity of 7.4 µM. These values agree well with literature values determined by accepted methods. Unlike those methods, PLIMSTEX provides site-specific binding information. The second approach, modified SUPREX (stability of unpurified proteins from rates of H/D exchange) coupled with electrospray ionization (ESI), allowed us to obtain detailed understanding about apoE unfolding and its changes upon ligand binding. Three binding regions, along with an additional site, which may be important for lipid binding, show increased stability (less unfolding) upon ligand binding. By employing a single parameter ΔC1/2%, we compared relative changes of denaturation between peptides. This integrated platform provides information orthogonal to commonly used HDX kinetics experiments, providing a general and novel approach for studying protein–ligand interactions.

Keywords: protein–ligand interaction, hydrogen deuterium exchange of proteins, mass spectrometry, protein binding affinity, unfolding, Apolipoprotein E, protein-ligand interactions by mass spectrometry, titration, HDX (PLIMSTEX), SUPREX

Graphical abstract

Introduction

The interaction of proteins with various ligands, their resulting stoichiometry, binding interfaces, conformational changes, thermodynamics, and kinetics are key to many biochemical processes. Although methods using fluorescence1 or Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR),2 provide essential binding constants, they often require specific reporter labels and afford limited if any spatial or site-specific information. High resolution methods (e.g., Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)3 and X–ray crystallography4), are often difficult because they require relatively large amounts of sample and considerable expertise. Hydrogen–deuterium exchange (HDX), because it is non-perturbing and simple to execute while providing high sensitivity and spatial resolution of the protein,5–9 has become one of the most applied mass spectrometry-based footprinting approaches in studying protein conformational change and locating protein–ligand interactions. Ligand binding can directly or indirectly affect protein local hydrogen-bond networks and change solvent accessibility. Backbone amide hydrogen exchange with D2O responds to these changes. In HDX kinetics, as most commonly practiced, the protein needs only to be incubated in D2O and time-dependent measurements made. Plots of deuterium uptake extent against exchange times, inform on binding regions when comparing HDX in the presence and absence of a ligand.7

To increase the utility of HDX, two methods have been advanced to determine protein–ligand binding affinities. One is PLIMSTEX (protein–ligand interactions by mass spectrometry, titration, and H/D Exchange),10 in which a protein in solution is submitted to HDX at a pre-determined time with increasing ligand concentration. A plot of HDX against ligand concentration produces a “PLIMSTEX curve”, from which binding affinity can be extracted by mathematical model fitting.11 In addition, at protein concentrations much higher than the ligand dissociation constant, PLIMSTEX can be used to determine binding stoichiometry or purity of the protein.10,12 PLIMSTEX is a titration-based platform employing the same idea as conventional fluorescence-based titration methods, but without introducing a fluorophore, which often requires amino acid substitutions. An HDX method allows a protein to be investigated in solution in its native or near-native state.

PLIMSTEX has been successfully applied to a variety of complicated systems in which binding affinities estimated at the global level agree well with literature values.10,11,13–15 Its application at the peptide-level, however, has developed more slowly. One reason is that we chose for our development metal-binding systems that appear to involve multiple, more complicated binding processes14,15 than do the more tractable 1:1 systems. Additionally, application to tight binding requires low protein concentrations, which formerly was challenging but now readily addressed with today’s mass spectrometers.

SUPREX (stability of unpurified proteins from rates of H/D exchange), is another HDX-based method for measuring protein folding energy changes and binding constants.16 Although SUPREX was originally developed for application with matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) MS, it is also suitable for electrospray ionization (ESI) MS17. In SUPREX, a protein in the presence and absence of ligand is incubated with different concentrations of denaturant and then submitted to HDX as a function of deuterium exchange times. Each SUPREX curve is constructed by plotting the protein mass shift against denaturant concentration and fit to a four-parameter sigmoidal equation by nonlinear regression to determine a transition midpoint, . Multiple determinations at varied exchange times are used to calculate an m value18 (i.e., dependence of folding free energy change on denaturant) and ΔGf, (i.e, the folding free energy in the absence of denaturant). The binding constant can then be calculated from the ΔΔGf between bound and unbound states.19–21 Thermodynamics of domains22 or of large peptides23 can also be probed with SUPREX coupled with enzyme digestion.

We recently performed the usual differential HDX kinetics experiment of bound and unbound states of apolipoprotein E (apoE) and a small molecule effector (drug candidate).24 The apoE family consists of three isoforms that differ by single amino-acid changes at two sites out of 299 residues: apoE2 (Cys112/Cys158), apoE3 (Cys112/Arg158), and apoE4 (Arg112/Arg158).25 The motivation for our interest is apoE4, a major genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (AD)26; in contrast, apoE2 and apoE3 have no such detrimental effect.27 We found binding at three regions of the C-terminal domain: 229–235 (LDEVKEQ), 234–243 (EQVAEVRAKL) and 258–265 (QARLKSWF). To explore the potential of PLIMSTEX to characterize this system for local binding, we extended it by coupling it with tandem protease digestion and obtained binding constants at peptide levels. Additionally, we implemented a modified peptide-level SUPREX protocol to investigate regional binding-induced unfolding changes, particularly of the C-terminus.

Experimental

Materials and Reagents

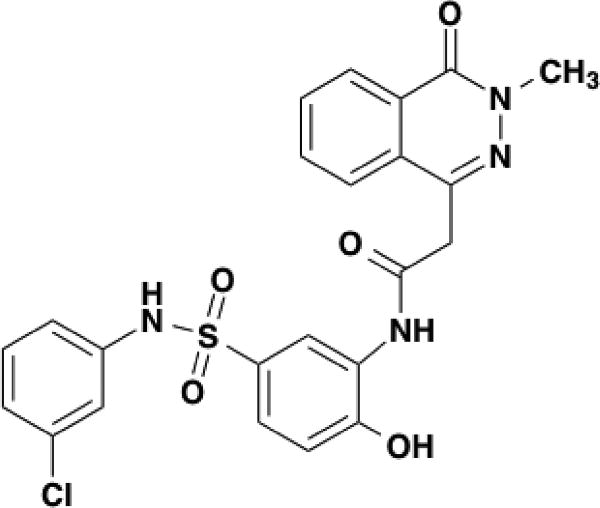

As previously reported24 and briefly described here, apoE3 was expressed as a thioredoxin fusion protein in E. coli that was grown in LB media to OD600 = 0.6. A PreScission peptide was inserted between the thioredoxin and apoE. After purification using an N-terminal 6X-Histag, thioredoxin was removed with the PreScission protease (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA). Phosphate buffer saline (PBS), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), dithiothreitol (DTT), urea, formic acid, trifluoroacetic acid, porcine pepsin, fungal XIII, HPLC grade water and acetonitrile were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). D2O was from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories Inc. (Andover, MA). The compound, N-5-[(3-chlorophenyl)sulfamoyl]-2-hydroxyphenyl-2-(3-methyl-4-oxo-3,4-dihydrophthalazin-1-yl)acetamide (C23H19ClN4O5S, name shortened to EZ-482), was from Enamine LLC (Monmouth Junction, NJ). The structure of this compound is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The structure of EZ-482.

Sample Preparation

For PLIMSTEX, 10 µM apoE3 (1X PBS containing 2 mM DTT, pH 7.4) was incubated with different concentrations of EZ-482 (dissolved in DMSO) for 1 h at 25 °C prior to HDX analysis. All stock solutions contained 2% DMSO including the apoE3 sample without ligand.

In the originally described SUPREX experiment, the protein was dissolved and submitted to denaturant and D2O exchange by including the denaturant in deuterated exchange buffers. In this work, the unbound and bound (10 µM apoE3 and 500 µM EZ-482; 1:50 protein:ligand) apoE3 solutions were incubated for 1 h at 25 °C. Then various concentrations of urea were added to the master solutions and incubated for 1 h at 25 °C again before HDX analysis. The final urea concentration was measured by a hand-held refractometer (Atago U.S.A., Bellevue, WA).

HDX Protocol

Both PLIMSTEX and modified SUPREX were conducted with the same HDX protocol24 after sample preparation. Briefly, HDX was initiated by 10-fold dilution of 4 µL stock solution into D2O buffer (1× PBS, pD 7.4) for 2 min at 25 °C, followed by mixing 2:3 (v/v) with 1 mg/mL fungal XIII, 3 M urea, and 1% formic acid on ice for additional 2 min. The quenched and fungal XIII digested peptides were then submitted to online pepsin digestion, trapped and desalted on an Agilent C8 trap column (2.1 mm × 1.5 cm, Santa Clara, CA). The sequentially digested and desalted peptides were then separated over 11 min on a C18 column (2.1 mm × 5 cm, 3 µm Hypersil Gold, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). Data were collected on a Bruker maXis quadrupole time of flight (Bremen, Germany) mass spectrometer via positive-ion ESI. The entire procedure was carried out in a custom-built water-ice bath to minimize back exchange. All data points were taken in duplicate.

Data Analysis

Peptides from sequential digestion prior to HDX analysis were submitted to collision-induced dissociation fragmentation (CID) on a Thermo LTQ 7 T FT-MS (San Jose, CA) in a data-dependent mode. Product-ion spectra were identified in MassMatrix (version 2.4.2),28 and manually verified. Deuterium uptake of each peptide was deconvoluted with HDExaminer (2.0, SierraAnalytics, Inc., Modesto, CA). No corrections for back exchange. For peptides whose deuterium uptake extent (HDX%) level off at high urea concentration, some (e.g. 79−93, 175−191, and 234−243) have <20% back exchange, whereas some shorter peptides (e.g. 229−235 and 264−271) have <40% back exchange.

Peptide-level PLIMSTEX data were analyzed by a customized program11 implemented in MathCAD (v14, Parametric Technology Corp., Needhad, MA). The program is available upon request. Briefly, a general model for specific binding was used to calculate species fractions as a function of postulated binding affinities and experimental ligand concentrations. Postulated species mass shifts were weighted by the corresponding species fractions to obtain a signal function, which was compared with the titration experiment data in a nonlinear least-squares fit. Satisfactory results were obtained with a 1:1 binding model in this case by fitting the data either independently for each of three binding regions or, after combining, considering that each peptide region is part of a single binding site. The first approach allowed each peptide to be independently fit with different ligand-binding models and signal functions, producing binding affinities for each peptide. In contrast, the simultaneous fit constrained the data from three peptides that displayed HDX difference to be fit with a single binding model but different signal functions to obtain a single binding affinity. A Bootstrap resampling strategy29 was employed for statistical evaluation of binding affinities, in which 4 k trial datasets were constructed by randomly resampling experimental data with replacement. Resampling times equaled the number of replicates at all ligand concentrations. Standard deviations were calculated from all trial Kd that were generated by each newly constructed PLIMSTEX curve.

SUPREX curves were fit to a four-parameter sigmoidal equation (1) using a nonlinear regression procedure30 and MathCAD. Because the percentage deuterium exchange used in this work is proportional to the mass shift, these two quantities were used interchangeably.

| (1) |

In equation 1, ΔMass[Urea] is the mass shift compared to non-deuterium exchanged mass at certain urea concentration. The term ΔM0 models mass shift before globally protected protons exchange with deuterium. [Urea] is the molar concentration of urea. is the half-way transition point of a SUPREX curve; a and b are unknown parameters describing amplitude and steepness of the transition region of a SUPREX curve.

The Bootstrap strategy was again used for statistical evaluation of precision with 16 k trial datasets. Each newly constructed SUPREX curve generated a trial . By using a Monte Carlo method,29 4 million random pairs of (i.e. for holo state) and (i.e. for apo state) were used to calculate ΔC1/2% with equation (2). The results for each peptide were compiled by using a histogram distribution with 101 bins. Empirical, two tailed p-values were calculated to report the significance of the difference between pairs of peptide ΔC1/2% distributions.

| (2) |

DFT calculations

Details of DFT calculations are provided in SI.

Results and Discussion

Putative binding sites

The kinetics of HDX reveals regions of a protein, represented by peptides, involved in conformational changes upon ligand binding. Decreased deuterium uptake of the holo state compared to the apo state suggests, but does not guarantee, the binding sites. Thus, we refer to the regions that show decreased HDX upon ligand binding as “putative binding sites”. Although these different peptide regions may all respond to one ligand binding (i.e. all responsive regions constitute one binding site that is discontinuous, as in multi-valent metal binding or multi-epitope antigen binding), they could represent different binding sites.

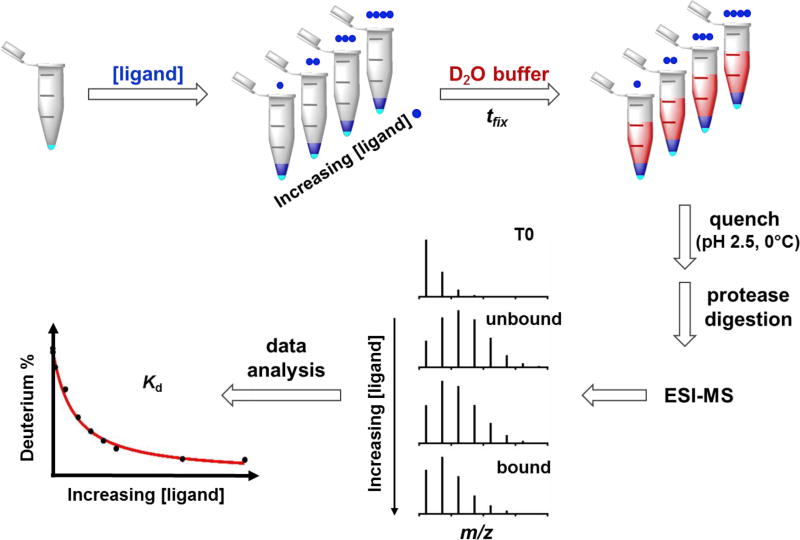

The workflow of PLIMSTEX begins with incubation of protein aliquots with increasing ligand concentration, then initiation of HDX at a fixed time (tfix), followed by sample digestion and analysis (Figure 2). It is important to find an appropriate tfix at which there is a significant HDX difference between bound and unbound states (i.e., a large difference between the starting and end point on the titration curve) to optimize accuracy. The precision of the measurements can be further improved if deuterium exchange at this time point is nearly constant. Based on our previous HDX study,24 we chose to sample the system at 2 min, at which time the HDX difference between bound and unbound states is sufficient for analysis, and the kinetic curve of the bound state is not steep and highly time-sensitive. Considering that there is no difference of EZ-482 binding properties to the C-terminal domains of apoE3 and apoE4 as determined by multiple methods,24 we carried out this work with apoE3 for the purpose of characterizing more completely this system and demonstrating the extensions of PLIMSTEX and SUPREX at the peptide level of the full protein.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of peptide-level PLIMSTEX workflow. Protein (cyan) is first incubated with a solution containing increasing concentration of ligand (blue). Deuterium buffer (red) is then mixed and incubation occurs for a fixed time (tfix). HDX is quenched and the protein is submitted to protease digestion. Centroid deuterium incorporation for the responsive peptide is decreased from unbound to bound state. Binding affinity is extracted from fitting of PLIMSTEX curve that is obtained by plotting HDX extent against ligand concentration.

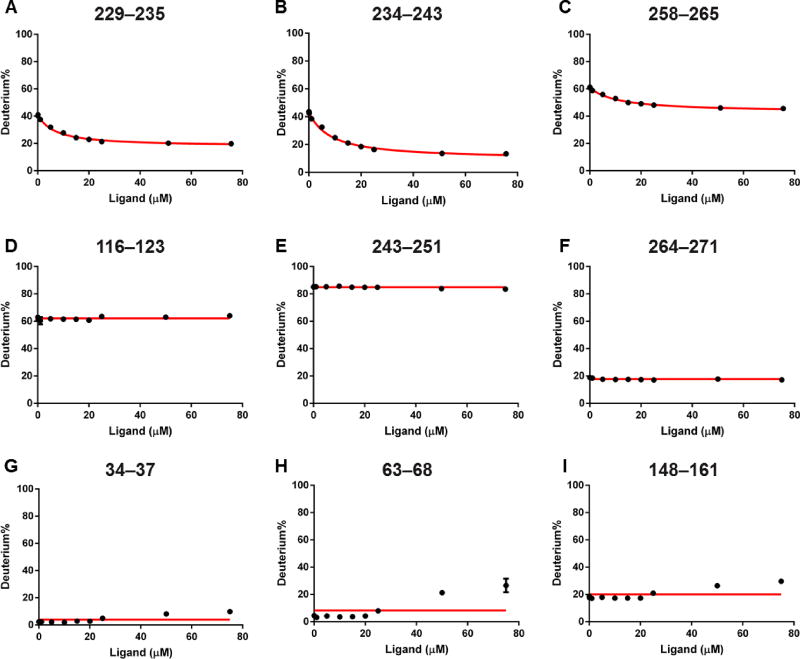

PLIMSTEX curves show binding at three different regions revealed by the peptide-level data; each can be used for obtaining binding affinities (Figure 3; curves covering the entire protein sequence are in Figure S1). Only these three regions, 229–235, 234–243 and 258–265, represented by corresponding peptides, exhibit a decrease in HDX extent upon increasing the concentration of EZ-482 (Figure 3A–C; data fitting of the three regions is discussed in the next section). Decreases of HDX with increasing ligand concentrations indicate increased protection by direct interaction with ligand or as a remote conformational change. Nearby regions adjoining 243–251 and 264–271 display no HDX change with increasing ligand concentrations (Figure 3E–F). Another region, as represented by peptide116–123, shows no HDX change and is included to represent regions in the N-terminal domain that do not change (Figure 3D). A horizontal line (red) at the average HDX value across all time points is drawn in the figure to guide the eye. This constant HDX extents in the PLIMSTEX curves of three peptides, ranging from protected areas (~ 20% HDX) to intermediate (~ 60% HDX) and flexible regions (~ 80% HDX), represent the majority of the protein and can be viewed as negative controls for those regions that do change in PLIMSTEX (Figure S1). Only peptides showing a decrease in HDX are likely to be involved in ligand binding, although we cannot completely rule out that peptides with no HDX response may also be involved in ligand binding (this concern also applies to HDX kinetics).31

Figure 3.

PLIMSTEX curves of (A)–(C) of peptides representing putative binding sites that show a gradual HDX decrease; (D)–(F) representative peptides from both N-terminal and C-terminal domains displaying no HDX response against ligand concentration; (G)–(I) representative peptides in N-terminal domain showing increased HDX at high concentration of the ligand. Red lines in (A)–(C) are 1:1 fitting curves, and the horizontal lines are averaged HDX across all time points in (D)–(I).

Interestingly, a third class of behavior is seen for peptides representing regions 34–37, 63–68, and 148–161 (Figure 3G–I) as well as 27–30 and 52–62 (Figure S1). HDX, initially constant, starts to increase at high concentration (50 and 75 µM) of the ligand. We did not observe this de-protection in the N-terminal domain of apoE3 in previous kinetics experiments24 because the ligand concentration used to examine the bound state was smaller (25 µM). We do not know the cause of this weak effect but suggest that the ligand acts as a denaturant at high concentration. The ligand could affect locally the environment of the N-terminal domain, either directly or through the C-terminal domain when the ligand concentration is high.

Binding affinities at regional level of apoE

Next, we want to determine the binding affinities at the regional levels by fitting the three PLIMSTEX curves (i.e., for regions 229–235, 234–243 and 258–265) independently. A satisfactory fit of each peptide (R2 = 0.99) with a 1:1 binding model affords binding constants of 6.0 ± 0.3, 6.8 ± 0.3, and 10.6 ± 0.5 µM, respectively. We did not constrain the last titration point as 100% bound state because the highest ligand concentration we can achieve without experiencing solubility issues after dilution was 75 µM (compared to 1 µM protein concentration). We assumed each region binds the ligand 1:1. Results from independent fits of the three peptides indicate their binding constants are essentially the same (within a factor of 2), strongly suggesting that each is part of a single binding region. Assuming the three regions are part of a single binding site, we also fit simultaneously the data for the three peptides and acquired an “average” binding constant of 7.4 ± 0.3 µM. The R2 value of overall fit is slightly improved compared to individual fits, probably because more titration points are involved. This treatment reflects binding at global level because contributions from all putative binding sites are considered. Indeed, this single “global” dissociation constant (7.4 µM) is very close to the average value of three locally fit results (7.8 µM).

Instead of ligand binding simultaneously to three different regions, it is possible that binding to region 258–265 involves a different protein conformation given its slightly larger, different dissociation constant (10.6 ± 0.5 µM vs. 6.0 ± 0.3, 6.8 ± 0.3 µM). Although the HDX technical precision is sufficient to discriminate, biological replicates, which bear higher errors,32 are not tested here. There may be other small, systematic differences in the protein or protocol, and in the absence of other evidence, we prefer to classify the three regions as part of the same binding phenomenon.

Another issue for mass spectrometry-based footprinting methods is that regional differences between two states can occur because there are remote conformational changes resulting from the binding. We assume that if any of the responsive regions are not a direct binding site, the “global” fitting would be less accurate than the individual local fitting as regions that are not involved directly in ligand binding may introduce uncertainty in the “global” fitting. Indeed, PLIMSTEX at global level (i.e., no enzyme digestion, no bottom up analysis) gives a readout that is a combination of responses of both direct interaction and conformational change to ligand binding. Thus, executing PLIMSTEX at the peptide level to obtain regional binding affinities, even for the simplest 1:1 binding system, is preferred.

For comparison, several fluorescence-based techniques, including measuring fluorophore signals of a cysteine mutant, also give binding affinities of EZ-482 to apoE, as described in our previous report.24 These methods all assumed a 1:1 binding system, yielding binding affinities within a range of 5–10 µM under different conditions. Binding affinities determined by PLIMSTEX (i.e., 6.0, 6.8, 10.6 µM for individual fits, and 7.4 µM for an overall fit) agree well with that range. An advantage of PLIMSTEX, however, is that it does not require introduction of specific probes or additional amino acids that may perturb protein structure. Additionally, conformational changes and binding affinities of various binding sites can be monitored in a single PLIMSTEX experiment.

One of the complications of using apoE isoforms in biophysical studies is their tendency to self-associate. ApoE exists in a lipid-free solution as a mixture of monomer, dimer, and tetramer even at low micromolar concentrations.33–35 Regions 229–235, 234–243 and 258–265, which are involved in ligand binding, also may be protein self-association interfaces36. Although it is unclear how each apoE subunit is oriented in the oligomer, it is possible, for example, that the ligand binds to region 229–235 and 234–243 on one subunit and affects peptide 258–265 on another subunit in the oligomer. On the other hand, the interaction between EZ-482 and apoE3 is likely to be multi-valent, and all three regions interact with one ligand directly.

The fact that the binding interfaces overlap with the oligomer interface raises a concern that the binding affinities measured by PLIMSTEX may be compromised with oligomer association/dissociation because both processes can affect the signal readout we used (HDX). Fortunately, the distribution of apoE oligomers is not affected by EZ-482 binding according to analytical centrifugation.24 Additionally, the PLIMSTEX results are consistent with binding affinities measured by fluorescence experiments, in which protein concentrations were slightly lower (0.5 µM), and the fluorophores were introduced at non-oligomerization interfaces.24 These observations indicate that oligomerization is not an important issue when considering the ligand binding to apoE. Therefore, we interpret the successful fit as indicating that this is a 1:1 binding system as one ligand bound per protein, independent of the protein oligomeric states.

Unfolding followed by SUPREX

Lipid binding to apoE is associated with a large conformational change of the protein.37 Studying the effect of EZ-482 binding on protein unfolding at the peptide level should provide insight into how this ligand affects apoE lipid binding. SUPREX, another approach involving HDX but reporting on thermodynamic-stability changes, should be useful for this purpose. We modified the canonical SUPREX approach to evaluate unfolding profiles at the peptide level upon ligand binding, with a strong interest in the C-terminus. SUPREX is analogous to the chemical denaturation equilibrium assay typically measured by circular dichroism (CD) at the global level of a protein. Reasons to choose SUPREX are that it can provide information at the peptide or regional level, and it has high sensitivity. High sequence coverage is not necessarily required because a single peptide with a well-defined SUPREX curve is sufficient to represent the global or sub-global stability change induced by ligand binding.23 Representative peptides in domains of interest should be sub-globally protected, insensitive to local fluctuations, and not solvent accessible.22

Our modification of SUPREX is motivated to characterize denaturation of various regions of the C-terminal domain where binding of the ligand occurs, to gain more information about ligand binding. Conventional SUPREX requires multiple HDX experiments performed at different deuterium exchange times to extract the binding affinity. We acquired only one SUPREX curve for each state because we are mainly interested in qualitative comparisons between the apo and holo states, having already determined the binding constants. We used the same exchange time (i.e., 2 min) as for PLIMSTEX, to permit comparisons. At 8 M denaturant before diluting with D2O, ApoE is unfolded. The most important change is that we diluted the urea concentration by adding pure D2O, causing partial protein renaturation of the N-terminus, as shown by other spectroscopic methods,38,39 but not of the interesting C-terminus. Indeed, the overall denaturation of ApoE is biphasic as the N- and C-terminal domains unfold and fold independently.38,39 The C-terminal domain completely unfolds before the N-terminal domain starts to unfold, over the range of 0–2 M urea and 3–6 M urea, respectively.39 Owing to the difference in the domain stabilities of apoE, the modified SUPREX approach allows us to investigate complete unfolding of the C-terminal domain and to verify renaturation of the N-terminal domain.

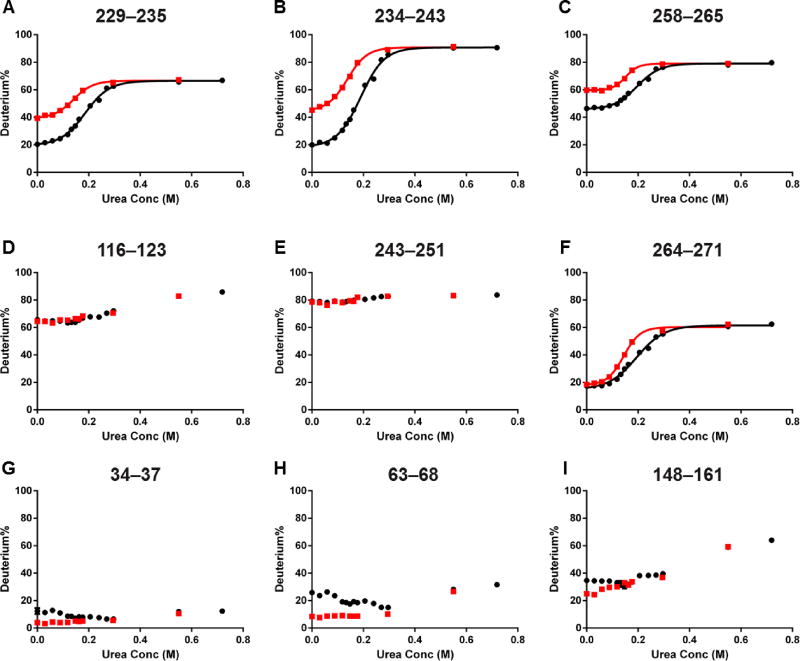

We plotted the deuterium uptake of bound and unbound states as a function of urea concentration (after D2O dilution) to obtain SUPREX curves and found good consistency between the SUPREX and PLIMSTEX, as shown in Figure 4 (SUPREX curves of peptides from the entire sequence are in Figure S2). The SUPREX curves are particularly informative for the putative binding regions 229–235, 234–243 and 258–265 (Figure 4A–C). The bound state undergoes less HDX than the unbound in the absence of denaturant, consistent with PLIMSTEX. The SUPREX curve of the bound state shifts to the right of that of the unbound for all three peptide regions, indicating increased stability induced by ligand binding. That the HDX%’s of the four peptides reach plateaus over the range of 0–0.2 M urea, if corrected for the 10-fold dilution by adding D2O, is consistent with the literature reports on denaturation.39

Figure 4.

Modified SUPREX results for the same set of peptides as in Figure 3. Red squares are data from the unbound state, and black dots are from the bound state. Data fitting is performed with four peptides showing complete unfolding profiles (A)–(C), (F).

Unlike the above peptides, most peptides in the C-terminus do not show any HDX difference between bound and unbound states in the HDX kinetics experiment,24 do not change with ligand concentration in PLIMSTEX, and afford nearly identical SUPREX curves for both bound and unbound states (Figure 4D and E for representative peptides). Those peptides representing flexible or solvent-accessible regions that carry little information about protein unfolding over the exchange time. The only exception is peptide 264–271 from the C-terminal domain. There is initially no HDX difference between two states in the absence of denaturant for this peptide, consistent with the kinetics and PLIMSTEX results (Figure 4F). The SUPREX curve of the bound state, however, is shifted to the right of that of the unbound state, indicating increased stability upon ligand binding. This peptide must be relatively rigid or located at a solvent-inaccessible region, considering the low initial HDX extent (~ 20%) compared to other peptides. Behavior of this region demonstrates an advantage of SUPREX that a peptide representing a protected region can reveal the stabilizing influence of ligand binding whether or not there is a conformational change upon ligand binding. Interestingly, region 261–272 is reported to be important for lipid binding,40,41 suggesting that the EZ-482 ligand could potentially affect protein–lipid interactions. This detail would be missed if the entire protein sequence is not covered in the HDX experiment.

As predicted based on previous knowledge about apoE unfolding and observed in the modified SUPREX experiment, peptides without high initial HDX in the N-terminal domain do not produce complete SUPREX curves (Figure S2) because the denaturation scope used in this work is designed to probe the C-terminal domain and is insufficient to maintain complete denaturation of the highly structured N-terminal helix bundle37,42 upon D2O dilution. At the highest urea concentration, HDX of peptides 34–37 (<10%), 34–43 (<40%) remains the same as for the apo state, suggesting no denaturation (complete renaturation) of this region. In contrast, HDX of peptide 102–109 increases from <10% to 80%, indicating complete denaturation (no renaturation) in this region. Between the two extremes is region 148–161, for which HDX increases from ~20% to 60%, an indication of partial unfolding. Our HDX data suggest that helix 1 (residues 26–40)37 is more stable than other helices in the N-terminal domain. For those regions that show increased HDX at high ligand concentrations (50 and 75 µM) in the PLIMSTEX experiment (Figure 3G–I), the corresponding SUPREX curves of the bound state (50 µM ligand concentration) start at a higher HDX, decrease to the same level as that of the unbound state before increasing again in a similar way as the unbound state (Figure 4G–I). Although both ligand dissociation and denaturation can cause the higher HDX, separating these two factors cannot be done for the C-terminal domain. At the N-terminal domain, however, the ligand interaction reduces its stability. Decreasing the effective ligand concentration should reverse this “denaturant” effect, and return HDX to a lower level. That HDX of representative peptides in the N-terminal domain decreases before increasing indicates that urea initially attenuates the ligand interaction before unfolding the protein.

This modified SUPREX experiment is designed as a differential study of protein unfolding between an apo and holo state with no intent to obtain binding affinity. One modification, not adding denaturant in the D2O buffer, allows us to harmonize the deuterium labeling step between PLIMSTEX and modified SUPREX for comparison; such a protocol is sufficient for a domain (protein) that is relatively easy to unfold. For highly structured domain/protein, however, one would use deuterium buffer containing the same amount of denaturant or a smaller dilution factor to avoid protein renaturation during deuterium labeling step.

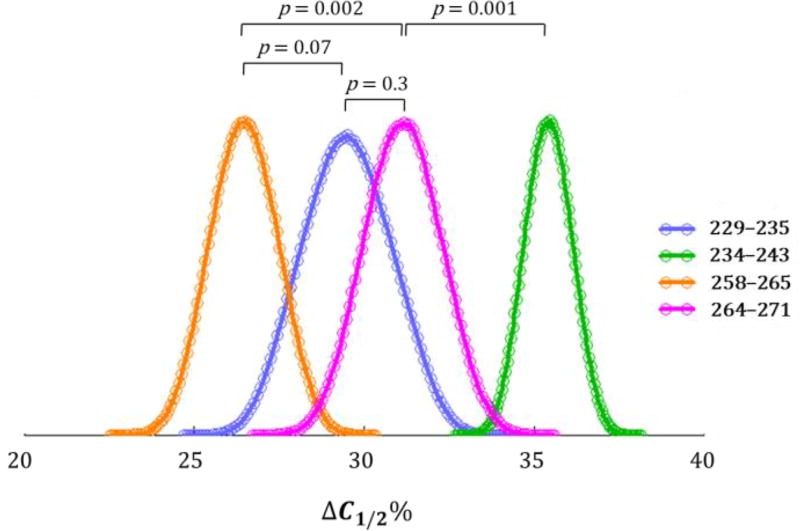

SUPREX reports different local binding-induced unfolding change

Next, we are interested in investigating the unfolding changes upon ligand binding for the four peptides 229–235, 234–243, 258–265, and 264–271 in the C-terminal domain to identify the most sensitive region for ligand binding. We employed a single parameter, ΔC1/2%, the relative unfolding change upon ligand binding for comparison. Denaturation signals are not only a result of free energy changes (ΔGf) but also affected by the dependence of ΔGf on denaturant (m).43 Both parameters contain information of changes induced by ligand binding. Therefore, we chose the relative unfolding change, ΔC1/2%, instead of absolute halfway transition shift , for a fair comparison between different regions.

To utilize full statistical value of the data, we combined Bootstrap and Monte Carlo approaches29 to generate a histogram of ΔC1/2% (Figure 5). The peak point of each distribution is the most probable value, and the width of the distribution is a measure of the precision (Table 1). We also calculated two-tailed empirical p-values for statistical evaluation of the differences between each distribution. The value of ΔC1/2% for peptide 234–243 is significantly larger than that of the other three (p = 0.001 when compared to the closest distribution), indicating that this region is the most sensitive to unfolding upon ligand binding. Unfolding responses of peptide 229–235 and 264–271 are similar (p = 0.3), whereas ΔC1/2% of peptide 258–265 is significantly smaller than that of peptide 264–271 (p = 0.002), but not comparable to the adjacent peptide 229–235 (p = 0.07) using a p-value cutoff 0.05. This p = 0.07 value, however, approaches the borderline of significance, suggesting a difference.

Figure 5.

Histogram of ΔC1/2% for peptides 229–235 (blue), 234–243 (green), 258–265 (yellow), and 264–271 (magenta). Each empty circle is a bin for grouping Monte Carlo random sampling results. Each p-value for comparing two peptides is listed above the two profiles.

Table 1.

| ΔC1/2% | ΔHDX% | |

|---|---|---|

| 229–235 | 30 ± 1 | 20 ± 1 |

| 234–243 | 35 ± 1 | 30 ± 1 |

| 258–265 | 26 ± 1 | 16 ± 1 |

| 264–271 | 31 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 |

See equation (2) and experimental section for calculation details.

HDX difference between unbound and bound state.

There is a correlation between ΔC1/2% and the amplitude of PLIMSTEX curve ΔHDX% (i.e., HDX change from the beginning to the end) for the three regions representing the putative binding sites (Table 1). The region represented by peptide 234–243 possesses the largest ΔC1/2% and ΔHDX%, whereas that of 258–265 has the smallest values for both. Region 264–271, one not directly involved in ligand binding, serves as a negative control showing that PLIMSTEX and SUPREX are independent but complementary methods. We suggest that region 234–243 is the most sensitive to ligand binding followed by those of 229–235 and 258–265, considering both methods point to the same trend. It is of interest to test whether this correlation between the two methods holds up with other protein/ligand systems.

Candidates of binding sites for EZ-482

The pKa of EZ-482 may provide insights on the binding mechanism and help locate the site of its binding. To this end, we performed DFT calculations to determine its pKa (see details in SI). The results indicate that the first ionization of EZ-482 is at pH = 6.9 and involves the phenol group. The sulfonamide is less acidic with a pKa of 9.6. Thus at the pH = 7.4 used here, EZ-482 largely carries one negative charge. Three putative binding regions, 229–235 (LDEVKEQ), 234–243 (EQVAEVRAKL) and 258–265 (QARLKSWF), all contain positive-charged residues, suggesting that EZ-482 interacts with the protein via electrostatics. Additionally, hydrogen bonds may form between EZ-482 and the three binding regions. In either binding mechanism, the three putative binding sites are available to interact directly with EZ-482.

Conclusion

Compared to conventional spectroscopic approaches to affinity and unfolding, HDX-MS based methods require no site-specific mutagenesis for introducing optical probes, thus avoiding perturbation of native protein structure. Unlike most other methods, HDX can give regional resolution when it is coupled with enzyme digestion. The two approaches used in this work can be viewed as orthogonal approaches to the widely adopted HDX kinetics experiment. With standard differential HDX kinetics, a protein with and without ligand is amide exchanged as a function of time to afford a comprehensive picture of protein structure and dynamics over a wide range of exchange times (seconds to days). In PLIMSTEX, however, HDX is followed at a single time point as a function of ligand concentration to give, additionally, binding affinities at both regional and “global” levels. The affinities determined here agree with those from other methods. Peptide-level results should also be more precise because they do not include regions not directly involved in ligand binding; such regions may “dilute” the global-level information. Further, peptides respond more sensitively to MS than do whole proteins.

The SUPREX experiment provides information in another dimension by monitoring HDX with increasing denaturant concentration to follow denaturation of both bound and unbound states. Unlike “high-turnaround” SUPREX, which gains a throughput advantage at the expense of reduced structural resolution by focusing only on a domain portion,22 SUPREX over the entire sequence reports on ligand-induced unfolding changes at different regions of the protein, giving a more fundamental view. The modified approach used here focused on the C-terminal region that contains the three binding regions. These regions show increased stability upon ligand binding, demonstrating consistency between the methods. An additional peptide, 264–271 in the C-terminal domain, displays the same behavior as the binding regions, reflecting a sub-global stability change upon ligand binding. Statistical analysis shows that region 234–243 is the most sensitive to ligand-induced unfolding change.

This integrative approach should be considered for future applications because binding interfaces, affinities, and thermodynamics are key to protein–ligand interactions. Ongoing experiments include applying peptide-level PLIMSTEX to more complicated binding systems involving binding of more than one ligand (e.g. 2:1, 4:1).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, NIGMS grant P41GM103422 (MLG) and by NIH RF1 AG044331 (CF). We are grateful to Berevan Baban for providing protein samples, Dr. Chris M.W. Ho for insights on protein/ligand interactions, and Dr. Jagat Adhikari for helpful discussion on SUPREX data interpretation.

Footnotes

The supporting information is available on the ACS Publications website at DOI:

PLIMSTEX results of peptides representing the entire protein sequence; SUPREX results of peptides representing the entire protein sequence; details of DFT calculations.

References

- 1.Yan Y, Marriott G. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:635–640. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Willets KA, Van Duyne RP. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2007;58:267–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.58.032806.104607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalvit C. Drug Discov Today. 2009;14:1051–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis AM, Teague SJ, Kleywegt GJ. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2003;42:2718–2736. doi: 10.1002/anie.200200539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engen JR. Anal Chem. 2009;81:7870–7875. doi: 10.1021/ac901154s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konermann L, Pan J, Liu YH. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:1224–1234. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00113a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chalmers MJ, Busby SA, Pascal BD, West GM, Griffin PR. Expert review of proteomics. 2011;8:43–59. doi: 10.1586/epr.10.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Englander SW. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2006;17:1481–1489. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woods VL, Jr, Hamuro Y. Journal of cellular biochemistry. Supplement. 2001;(Suppl 37):89–98. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu MM, Rempel DL, Du Z, Gross ML. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:5252–5253. doi: 10.1021/ja029460d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu MM, Rempel DL, Gross ML. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2004;15:388–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu MM, Chitta R, Gross ML. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2005;240:213–220. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sperry JB, Shi X, Rempel DL, Nishimura Y, Akashi S, Gross ML. Biochemistry. 2008;47:1797–1807. doi: 10.1021/bi702037p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sperry JB, Huang RY, Zhu MM, Rempel DL, Gross ML. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2011;302:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang RY, Rempel DL, Gross ML. Biochemistry. 2011;50:5426–5435. doi: 10.1021/bi200377c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghaemmaghami S, Fitzgerald MC, Oas TG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8296–8301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140111397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang L, Sundaram S, Zhang J, Carlson P, Matathia A, Parekh B, Zhou Q, Hsieh MC. MAbs. 2013;5:114–125. doi: 10.4161/mabs.22695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greene RF, Jr, Pace CN. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:5388–5393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powell KD, Ghaemmaghami S, Wang MZ, Ma L, Oas TG, Fitzgerald MC. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:10256–10257. doi: 10.1021/ja026574g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powell KD, Fitzgerald MC. Biochemistry. 2003;42:4962–4970. doi: 10.1021/bi034096w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang L, Hopper ED, Tong Y, Sadowsky JD, Peterson KJ, Gellman SH, Fitzgerald MC. Anal Chem. 2007;79:5869–5877. doi: 10.1021/ac0700777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang L, Roulhac PL, Fitzgerald MC. Anal Chem. 2007;79:8728–8739. doi: 10.1021/ac071380a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hopper ED, Pittman AM, Tucker CL, Campa MJ, Patz EF, Jr, Fitzgerald MC. Anal Chem. 2009;81:6860–6867. doi: 10.1021/ac900854t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mondal T, Wang H, DeKoster GT, Baban B, Gross ML, Frieden C. Biochemistry. 2016;55:2613–2621. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weisgraber KH, Rall SC, Jr, Mahley RW. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:9077–9083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small GW, Roses AD, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA. Science. 1993;261:921–923. doi: 10.1126/science.8346443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu CC, Kanekiyo T, Xu H, Bu G. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:106–118. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu H, Freitas MA. Proteomics. 2009;9:1548–1555. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manly BFJ. Randomization, bootstrap, and Monte Carlo methods in biology. 3. Chapman & Hall/ CRC; Boca Raton, FL: 2007. p. 455. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang MZ, Shetty JT, Howard BA, Campa MJ, Patz EF, Jr, Fitzgerald MC. Anal Chem. 2004;76:4343–4348. doi: 10.1021/ac049536j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sowole MA, Konermann L. Anal Chem. 2014;86:6715–6722. doi: 10.1021/ac501849n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engen JR, Wales TE. Annu Rev Anal Chem (Palo Alto Calif) 2015;8:127–148. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anchem-062011-143113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Westerlund JA, Weisgraber KH. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:15745–15750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perugini MA, Schuck P, Howlett GJ. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36758–36765. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005565200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garai K, Frieden C. Biochemistry. 2010;49:9533–9541. doi: 10.1021/bi101407m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang RY, Garai K, Frieden C, Gross ML. Biochemistry-Us. 2011;50:9273–9282. doi: 10.1021/bi2010027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen J, Li Q, Wang J. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:14813–14818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106420108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morrow JA, Segall ML, Lund-Katz S, Phillips MC, Knapp M, Rupp B, Weisgraber KH. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11657–11666. doi: 10.1021/bi000099m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nguyen D, Dhanasekaran P, Nickel M, Mizuguchi C, Watanabe M, Saito H, Phillips MC, Lund-Katz S. Biochemistry. 2014;53:4025–4033. doi: 10.1021/bi500340z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanaka M, Vedhachalam C, Sakamoto T, Dhanasekaran P, Phillips MC, Lund-Katz S, Saito H. Biochemistry. 2006;45:4240–4247. doi: 10.1021/bi060023b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nguyen D, Dhanasekaran P, Nickel M, Nakatani R, Saito H, Phillips MC, Lund-Katz S. Biochemistry. 2010;49:10881–10889. doi: 10.1021/bi1017655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hatters DM, Peters-Libeu CA, Weisgraber KH. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:445–454. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pace CN. Trends Biotechnol. 1990;8:93–98. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(90)90146-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.