Abstract

Recognizing predictive relationships is critical for survival, but an understanding of the underlying neural mechanisms remains elusive. In particular it is unclear how the brain distinguishes predictive relationships from spurious ones when evidence about a relationship is ambiguous, or how it computes predictions given such uncertainty. To better understand this process we introduced ambiguity into an associative learning task by presenting aversive outcomes both in the presence and absence of a predictive cue. Electrophysiological and optogenetic approaches revealed that amygdala neurons directly regulate and track the effects of ambiguity on learning. Contrary to established accounts of associative learning however, interference from competing associations was not required to assess an ambiguous cue-outcome contingency. Instead, animals’ behavior was explained by a normative account that evaluates different models of the environment’s statistical structure. These findings suggest an alternative view on the role of amygdala circuits in resolving ambiguity during aversive learning.

To enhance their chance of survival animals learn to make predictions based on sensory cues in their environment. However, it is not clear how they identify stimuli that are relevant for specific predictions, and how they distinguish coincidence between environmental events from actual predictive relationships. If an outcome occurs both in the presence and the absence of a cue for example, a contingent and therefore predictive relationship between the two is no longer obvious. An understanding of how the brain assesses such ambiguity in cue-outcome relationships is missing, and most accounts of animal learning confound ambiguity in the environment’s statistical structure (i.e. which relationships are predictive or causal in the environment), and uncertainty about the strength of established associations (e.g. the probability with which an outcome follows a predictive cue).

We investigated how animals assess ambiguous predictive relationships using classical threat conditioning. In this paradigm animals come to display defensive responses to stimuli predicting dangerous or aversive events, after pairings of an initially neutral conditioned stimulus (CS), such as a tone, and a biologically salient unconditioned stimulus (US), such as a mild footshock1–4. Humans and non-human animals alike show graded contingency learning, depending on how well a given outcome is predicted by a sensory cue. In particular, rodents are known to exhibit reduced conditioning to a tone-CS if footshocks are presented both in the presence and absence of the tone, a phenomenon known as ‘contingency degradation’5.

The prevailing interpretation explains contingency degradation in terms of cue competition6–8, where multiple cues compete for the ability to predict an outcome by partitioning a limited associative strength. For example, it is thought that during contingency degradation, a strong association formed between the conditioning context and the shock-US reduces subsequent learning of the tone-shock association. This process is referred to as contextual blocking5,9, and is thought to be implemented in the brain through attenuation of US processing during tone-shock pairings when the US is already predicted by the context3,10. Alternatively, a strong contextual association could be competing with the tone-CS at the time of memory expression8. Importantly, either type of cue competition would rely on contextual learning, a hippocampus-dependent process.

Cue competition can be problematic under some circumstances, since it assesses the ambiguity of predictive relationships only indirectly: instead of checking for dependencies between variables and learning statistical structure by evaluating different models of the environment, it sidesteps model selection and learns associations between any contiguous cue-outcome pair in a competitive manner.

Suggesting a different view, a previous in-vitro study11 found that the cellular-level process thought to underlie aversive memory storage in the lateral amygdala (LA) is itself sensitive to stimulus contingencies. Thus the brain might possess neural mechanisms at the level of the amygdala to evaluate contingencies between environmental stimuli, without relying on cue competition.

To make predictions in a statistically principled way from a small number of observations, the learning mechanism needs to take into account the overall pattern of events in the environment and account for possibly complex interactions between the different cue-outcome associations. While there is strong evidence that sensory cues become associated with aversive (or rewarding) outcomes through strengthening of sensory input synapses in the LA during associative learning1–4, a principled learning strategy has to go beyond evaluating single cue-outcome contingencies in isolation.

An understanding of both the learning strategy animals use on the computational level, and of the neural circuitry involved is thus critical for identifying the circuit mechanisms and algorithmic level processes that could implement contingency evaluations in the face of ambiguity. Here we used a combination of behavioral and computational approaches together with optogenetics, electrophysiology and pharmacology to address these questions. We find that cue competition is not necessary for contingency degradation, and does not give a satisfactory explanation of this phenomenon. Instead, animal’s behavior is best explained by models that evaluate the overall statistical structure of the environment. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the amygdala tracks contingency changes in the environment, and we reveal its important role in resolving ambiguity during learning.

Results

Contingency evaluation independently of cue competition

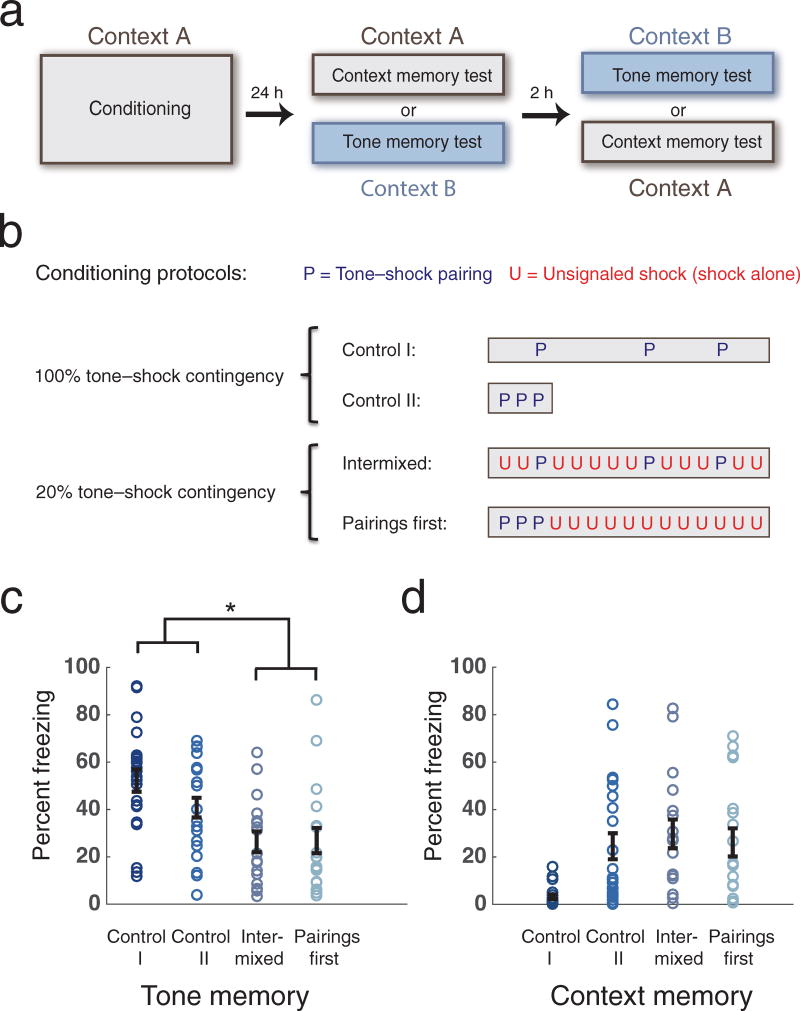

We first determined whether predictions of the cue competition models were supported when ambiguity in the ability of a given CS to predict the US was high. To test this we first examined trial order sensitivity and the relationship between Context and CS memory strength by varying the order of CS-US pairings and unsignaled USs (UUSs). Animals were given either three massed tone-shock pairings before, or three spaced tone-shock pairings intermixed with 12 unsignaled shocks (Pairings first and Intermixed groups respectively, both with 20% contingency), and tested for aversive memories by measuring contextual and tone-evoked freezing 24h later (Fig. 1a,b). Control I and II animals were given three CS-US pairings only (100% contingency). The Control I group received three CS-US pairings spaced (identical to the Intermixed protocol) but with all UUS omitted. The control II group received massed CS-US pairings identical to the Pairings First group, with the subsequent UUSs omitted, and conditioning terminated after the third CS-US pairing (Fig. 1b). Animals showed similar levels of tone-evoked freezing in both reduced contingency conditions, and these freezing levels were significantly lower than for Control animals (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 1). Animals were therefore sensitive to the ambiguity of the CS-US relationship and demonstrated the ability to integrate contingency information irrespective of the temporal order of training trials, contradicting a traditional cue competition based ‘contextual blocking’ account of contingency degradation.

Figure 1.

Reduced CS-US contingency results in reduced CS memory, irrespective of trial order and with or without changes in context memory. (a) Experimental design. Animals underwent threat conditioning on day 1 and were tested for contextual and tone (or tone and contextual) memories 24 hours later. (b) Conditioning protocols. Rats received sequences of tone-shock pairings (P) and unsignaled shocks (U), or tone-shock pairings only. The boxes indicate time spent in the conditioning chamber, ~7 min for CTL II group and ~31 min for all other groups. (c) A 20% CS-US contingency during training leads to significantly lower CS-induced freezing compared to 100% contingency, whether unpaired shocks are given intermixed with, or after with tone-shock pairings (n=22, 22, 17, 18, 2-way ANOVA, no significant interaction F1,75 = 1.63, p=0.21, main effect for contingency F1,75 = 18.02, * p=0.00006, simple effects for contingency F1,75 = 15.0, p=0.0002, F1,75 = 4.48, p=0.038 for spaced and massed condition respectively)‥ (d) Context memory strengths for the same animals. Reduction of CS memory with degraded CS-US contingency is not explained by changes in context memory strengths, as there was no difference between context memories of Control II and Pairings First groups (2-way ANOVA, significant interaction F1,75 = 6.44, p=0.013, simple effect for contingency F1,75 = 0.00008, p=0.81, not significant). Error bars indicate s.e.m.

Cue competition could also account for contingency degradation beyond such a forward blocking account. Some learning models suggest competition between associations at the time of memory retrieval10 or trial-order independent cue completion based on statistical learning principles, such as when learning strength parameters for predictive cues or causes in a predetermined generative model of the US12. However, we observed a reduction in CS memory strength between the Pairings First and Control II groups without a corresponding change in Context memory strength (Fig 1d, see also Supplementary Fig. 2a and b for a time-binned analysis and a more salient conditioning context). This suggests that competition where a strong contextual association would suppress tone-evoked responding at the time of memory retrieval, also fails to account for contingency learning. Thus while under some circumstances there can be an apparent inverse relationship between the different cue-outcome associations (notably in the case of the spaced condition, where the low rate of shock delivery in the CTL I group results in low context freezing), this is not generally the case, and in particular is not necessary for the animals to learn a degraded tone-shock contingency. Looking at individual animals, we also observed that the correlation between tone and context freezing was positive in all four conditions (Supplementary Fig. 1).

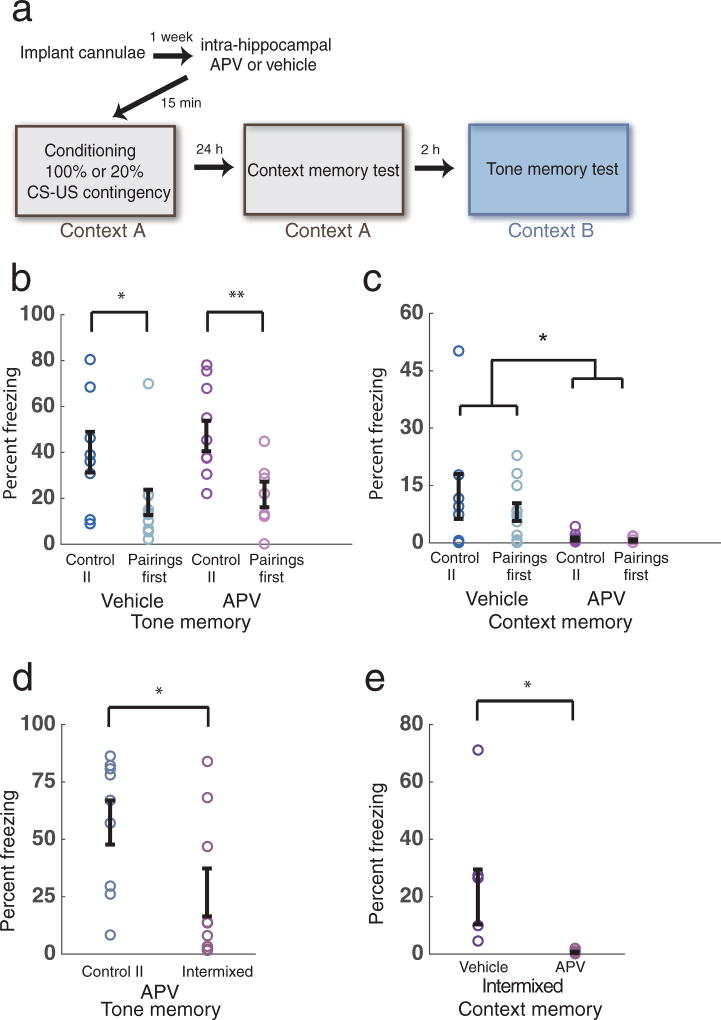

To better understand the influence of contextual associations on learning the tone-shock contingency, and to directly test for cue competition during learning and/or retrieval, we next infused the NMDA-receptor antagonist APV into the dorsal hippocampus (DH) prior to conditioning (Fig. 2a), a manipulation known to block the formation of contextual memories13. Consistent with previous results using a different paradigm14, this intervention had no effect on contingency degradation, despite significantly impairing contextual learning both in the spaced and the massed conditions (Fig. 2b–e). This provided further evidence that contingency degradation of auditory threat memories does not depend on competition between auditory and contextual cues, whether information about the reduced tone-shock contingency is delivered after tone-shock pairings, or the different types of shocks are intermixed (Fig. 2d, e). We further validated these results by comparing an alternative measure of threat response (defecation) in the spaced condition, and found that it paralleled our results measuring freezing (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Conditioning to the Context is not required for contingency degradation. (a) Experimental design depicting pharmacological inactivation of NMDA receptors in DH before conditioning. (b) Hippocampal APV injections have no effect on learning the reduced auditory CS-US contingency (n=8, 11, 10, 7, 2-way ANOVA, no significant interaction F1,32 = 0.07, p=0.79, main effect for contingency F1,32 = 11.98, p=0.0015, simple effect for contingency F1,32 = 8.60, * p= 0.011, F1,32 = 5.45, ** p= 0.026 for Vehicle and APV groups respectively). (c) NMDA receptor blockade impairs the acquisition of contextual aversive memories (2-way ANOVA, no significant interaction, F1,32 = 0.38, p= 0.54, main effect for drug treatment, F1,32 = 9.47, * p=0.0043). d) Similarly to the Pairings First case, contingency degradation to the auditory stimulus is unaffected in the Intermixed condition by APV infusion in DH (n=9, 9, unpaired sample t-test, t16 = 2.14, * p=0.048). (e) Impaired contextual aversive memory formation after NMDA receptor blockade in the Intermixed condition (n=7, 9, unpaired sample t-test, t14 = 2.31, * p=0.037). Error bars indicate s.e.m.

We also verified that the observed decrements in the tone-evoked responding were not due simply to delivering a larger number of shock USs (so-called ‘Reinforcer Devaluation’). Groups of animals that received 15 or 21 tone-shock pairings (Supplementary Fig. 4a) displayed similarly high levels of tone freezing, indicating that learning the tone-shock association was at a stable asymptote, and that the larger number of footshocks did not lead to a devaluation of this US. Further, if instead of delivering UUSs, shocks following the three tone-shock pairings were signaled by a second discrete CS (a flashing light), contingency degradation did not occur (Supplementary Fig. 4b), consistent with the so-called cover-stimulus effect15,16. Thus delivering a larger number of USs did not in itself cause contingency degradation; instead the animals’ learning reflected the precise environmental contingencies during learning.

LA neural activity controls and tracks contingency

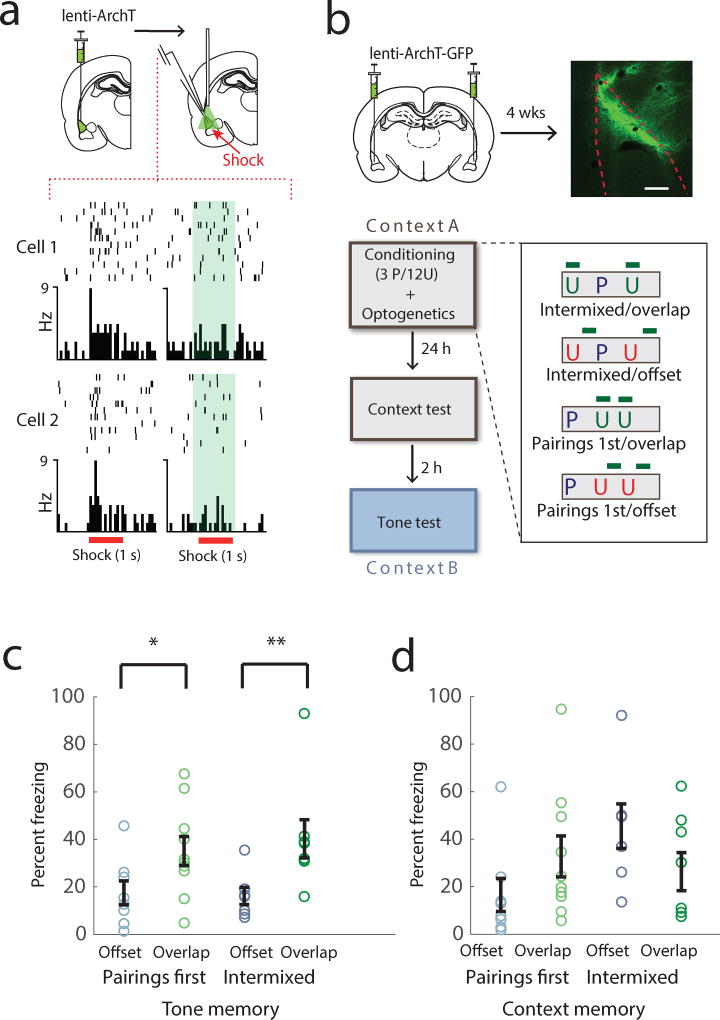

As animals could learn a reduced tone-shock contingency without relying on hippocampal plasticity and contextual memory formation, we next explored the role of the amygdala in contingency degradation. Previous research suggests that the amygdala is important for contingency evaluations during reward learning17,18. It is also well established that synaptic enhancement of auditory inputs to LA pyramidal neurons occurs during, and is necessary for auditory aversive learning, and that this enhancement is dependent on US-evoked activation of LA neurons coincident with the auditory CS1–4,19. A direct representation of the CS-US contingency needs to integrate information about the number of CS-US pairings vs. UUSs, so the activation of LA pyramidal cells by the UUSs could be an important trigger for learning contingency degradation. To test if this is the case, we expressed the outward-proton-pump Arch-T20 in these neurons, using intra-LA injection of a lenti-viral vector (Fig. 3a–b). In previous work 21 we demonstrated pyramidal cell specific targeting of Arch-T expression using this viral targeting approach and laser-induced inhibition of shock evoked responding in these cells (see figure Fig. 3a for further physiological demonstration of this technique). We used this approach here to test whether activity in LA pyramidal neurons during UUSs is necessary for the degraded contingency effects to occur. We found that inactivating these cells during UUSs, but not at other times in the conditioning session, rescued freezing to the tone on the long term memory test (Fig. 3b–c Suppl. Fig. 5), but caused no significant change in context memory (Fig. 3d). The US-evoked depolarization of LA pyramidal neurons can thus differentially modulate the strength of auditory aversive memories depending on its timing relative to the CS, and this can occur independently of changes in contextual memory strength.

Figure 3.

Activation of LA pyramidal cells during unsignaled USs is required to learn the degraded CS-US contingency. (a) Optogenetic inhibition of shock evoked firing rate (Hz) responses in single LA neurons. Perievent time rasters (top) and histograms (bottom) show shock evoked (red bars) responses in 2 example neurons without (left) and with optical inhibition (right, laser on denoted by green bar). (b) Design of optogenetic behavioral experiments. (top) Graphical depiction of lentivirus injection and example of Arch-T expression in LA pyramidal neurons (scale bar = 160 um). Virus expression within LA was verified for all experimental animals included in study. Experimental protocols with laser illumination either coinciding, or offset from UUSs (bottom). 3 tone-shock US pairings (P) were presented either intermixed with, or prior to 12 unsignaled USs (U). (c) Inactivation of LA pyramidal neurons during, but not offset from UUSs prevents the learning of the degraded auditory CS-US contingency (n=7, 8, 8, 10, 2-way ANOVA, no significant interaction, F1,29 = 0.28, p=0.60, main effect for inactivation, F1,29 = 11.41, p=0.0021, simple effects for inactivation F1,29 = 7.02, * p=0.013,, F1,29 = 4.45, ** p=0.044 for Pairings First and Intermixed groups respectively) (d) Context memory strength was unaffected by optogenetic manipulation (2-way ANOVA, significant interaction, F1,29 = 4.39, p=0.045, main effect for inactivation F1,29 = 0.0297, p=0.86, not significant, simple effects for inactivation F1,29 = 2.37, p=0.13, F1,29 = 2.03, p=0.17, not significant). Error bars indicate s.e.m.

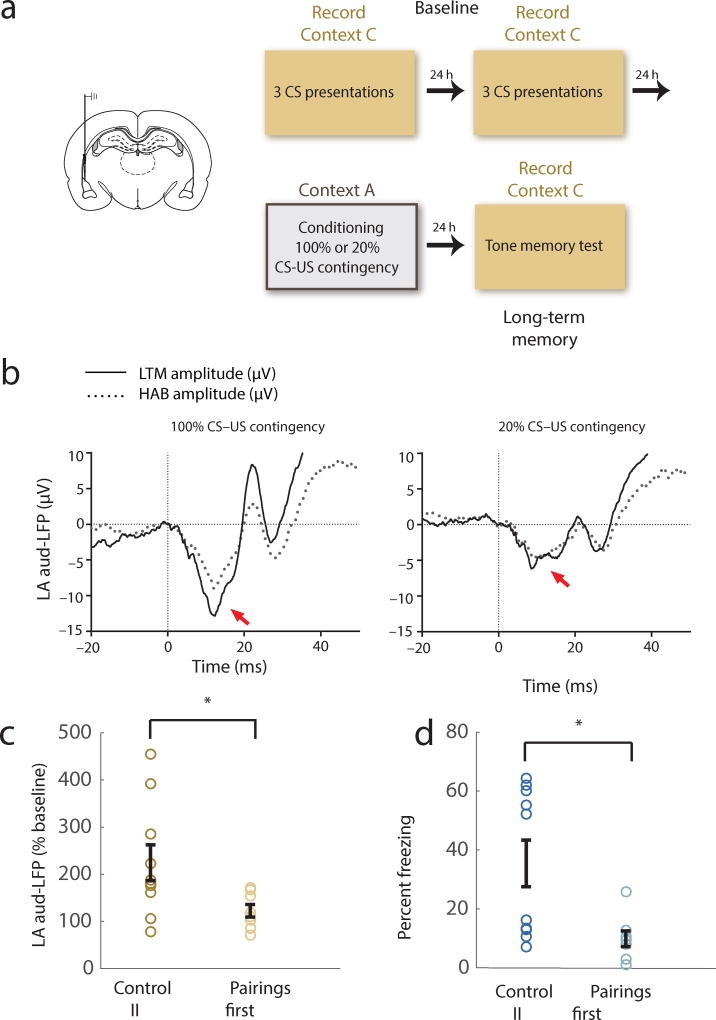

As discussed above, the enhancement of auditory input synapses in the LA underlies the expression of auditory aversive memories. Importantly, at the level of the LA this representation corresponds to the association between the sensory features of the auditory stimulus and aversive outcome and is not correlated with the motor output directly22. Additionally, previous work in humans23 and primates18,24 has indicated that amygdala neurons can adapt their activity according to the higher order structure of the task environment. A reduction in the overall enhancement of auditory processing in the LA could therefore regulate behavioral responses during retrieval in the case of contingency degradation. To test if this is the case, we next examined whether UUSs given after CS-US pairings reduced the learning induced enhancement of the auditory-evoked local field potential (A-LFP) response, a measure of synaptic enhancement in the threat learning circuit. We recorded A-LFPs in the LA before and after 3 tone-shock pairings (Control II protocol) or 3 tone-shock pairings followed by unpaired shocks (Pairings First protocol) (Fig. 4a). Consistent with previous findings, A-LFP was enhanced 24 hours after conditioning with 100% tone-shock contingency, however this enhancement was significantly reduced in animals that were trained with a reduced contingency (Fig. 4b–c Supplementary Fig. 6,7), paralleling a reduction in freezing behavior in the same animals (Fig 4d). Thus, consistent with the behavioral results the learning induced changes in auditory processing in LA reflects the broader environmental contingencies.

Figure 4.

Degraded CS-US contingency leads to reduced enhancement of CS processing in the LA. (a) Experimental design for the in-vivo physiology experiment. (b) Population-averaged A-LFP traces before (HAB), and after (LTM) conditioning in the Control II group (left) and Pairings First group (right). Vertical line at t=0 indicates CS onset, red arrow indicates peak depolarization. (c) Population averaged post training A-LFP % pre-training baseline. Reduced CS-US contingency leads to reduced potentiation of auditory CS processing (n=10, 8, unpaired t-test, t11,1 = 2.54, * p=0.028). (d) Animals in the in vivo physiology experiment also showed reduced CS memory in the reduced contingency (Pairings First) condition (unpaired t-test, t11,0 = 3.07, * p=0.011). Error bars indicate s.e.m.

Assessing ambiguity with structure learning

Amygdala processing thus plays a key role in the learning and retrieval of an ambiguous CS-US relationship, and this learning doesn’t rely on cue competition, though it might incorporate more complex context-cue interactions. However, in the absence of cue competition it is not clear what computational strategy animals use to resolve ambiguity during associative learning. Addressing this question requires the establishment of a computational framework that can quantitatively account for our behavioral findings as well as predict the effects of the neural manipulations we performed, and account for known conditioning phenomena that arise due to ambiguity in the predictive relationship between cues and outcomes.

We propose a structure learning model (SLM) that directly assesses uncertainty in the environment’s statistical structure, determining which relationships are actually predictive by considering statistical dependencies (as well as temporal order and contiguity) between variables. Given events during conditioning, SLM learns a posterior probability distribution over the possible sets of predictive relationships in the environment (represented by different graph structures, Fig.5a) using the formalism of Bayesian networks25, During retrieval, the strength of an association can be evaluated by calculating the posterior probability of a connection (a direct edge or a path in the graph) between the corresponding cue and outcome using a model-averaging procedure (Online Methods). Unlike simple cue competition, structure learning compares different configurations of interactions between variables and weighs these representations against each other. Such a model is able to learn a cue-outcome contingency even in the absence of a competing cue, while incorporating flexibility in the range of possible interactions between cues.

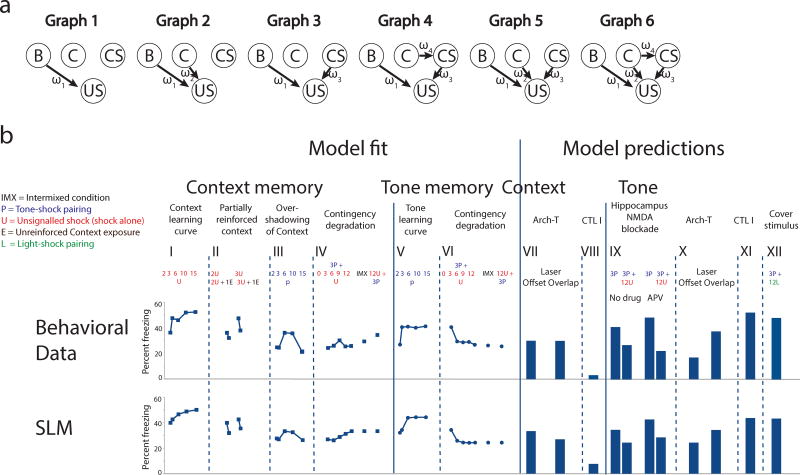

Figure 5.

Comparison of the fit of the structure learning model (SLM) and behavioral data. (a) The six different graphical representations of statistical associations in the environment that are compared in SLM. (b) Context and tone CS memory strengths (Behavioral data, top and SLM, bottom). Data points are % freezing at long term memory, after different conditioning protocols. Context memory: (I), 2, 3, 6, 10 or 15 unsignaled USs (UUSs). (II), 2 or 3 UUS followed by no or 1 unreinforced ITI in the conditioning chamber (III), 2, 3, 6, 10 or 15 CS-US pairings. (IV), 3 CS-US pairings followed by 0, 3, 6, 9, or 12 UUSs. Intermixed condition, and Pairings Last condition (3 CS-US pairings + 12 UUS). Tone memory: (V), Same groups as in III. (VI), Same groups as in IV. (SLM, bottom) Memory strength as predicted by SLM. Values are averages of 20 runs using the best-fit parameters. Model was fitted to data in I-VI. Best-fit parameters were then used to predict the effects of neural interventions (see Online Methods and Supplementary Modeling) and freezing scores for CTL I and Cover stimulus groups.

We examined whether this type of model could simultaneously explain responding to discrete cues and the conditioning context. We build on previous work characterizing human causal judgments using a structure learning approach26, extending it to the threat conditioning framework and to modeling neural interventions and more complex environments. We also provide a thorough analysis of the importance of the different components of the model in fitting a wide range of behavioral data.

To enable model fitting and comparison we collected further behavioral data in a manner similar to experiment 1 (Fig 1A), but using varied numbers of UUSs and CS-US pairings, allowing us to test which models can simultaneously explain learning under different conditions of ambiguity. In particular, if USs arrive only in the presence of the CS (i.e. only CS-US pairings are given) the association between Context and US is itself ambiguous, as it is not clear whether predictive power should be attributed to just the Context, or just the CS, or both27. We further included behavioral results for different degrees of contingency degradation, by varying number of UUSs after CS-US pairings.

We found that SLM successfully accounted for standard learning curves of context and tone memory strength (Fig.5b I, V) and predicted how associative strength is attributed under ambiguity, including the effects of contingency degradation (Fig. 5b IV, VI), the effects of partially reinforcing (or extinguishing) the context (Fig. 5b, II), and the u-shaped learning curve of the context memory strength during overshadowing by the CS (Fig.5b III). SLM could also account for freezing levels in the CTL I group (resulting from a low rate of shock delivery), and successfully explained our first experiment (Fig. 5b VIII, XI). In addition, SLM successfully predicted the effects of hippocampal NMDA receptor blockade, using the best-fit parameters from the behavioral data set, and predicted the result of the amygdala inactivation experiments (Fig. 5b, VII, IX, X). In summary, SLM was able to capture how the different associations interact in driving behavior both in cases where these interactions appear competitive, and in cases where there is an apparent dissociation or facilitation between associations.

A straightforward extension of SLM (Supplementary Fig. 8) that included a second CS (such as a light), but kept the best-fit parameters and scaling of the original model, could also account for a range of previously documented conditioning phenomena involving the assessment of ambiguous stimuli. SLM could thus account for the effects of signaling the UUSs with a second CS (the cover stimulus effect described above) and gave a good fit both for our replication of this phenomenon (Fig. 5b XII, Supplementary Fig. 9a), and qualitatively similar predictions to previous studies28 using related experimental paradigms (Supplementary Fig. 9a). The model’s prediction for other phenomena (including blocking10, overshadowing and recovery from overshadowing29) are further detailed in the Supplementary Materials (Supplementary Fig. 9b–d).

Model comparison

We compared SLM to three models that assume a fixed structure and evaluate contingencies by learning strength parameters for associations through some form of cue competition (Supplementary Fig. 10a–d and Supplementary Modeling). For the most direct comparison between a structure learning and parameter learning/cue competition approach, we fit a parameter learning model12, or PLM, that uses an identical Bayesian network representation, but assumes the maximally connected structure (Fig. 5a, Graph 6). PLM learns a strength parameter for each edge starting from flexible, independent prior distributions over these edge parameters, fit to best explain behavioral data‥ Despite this flexibility, the parameter learning approach that implements cue competition in a statistical learning framework did not capture well how animals evaluated contingencies across the different conditions (Table I, Supplementary Fig. 10c.)

Table 1.

Comparison of model fits. Mean squared error (MSE) for the best fit of each model, followed by the standard error, and the error in predicting the hippocampal interventions with each value representing % freezing squared. The Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) provides a principled measure of model comparison, taking into account the number of model parameters.

| Model | MSE | Standard Error of the MSE |

MSE for hippocampus APV injection |

Free Parameters |

Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure learning | 13.44 | 0.0054 | 34.03 | 2 | 88.82 |

| Structure & parameter | 12.61 | 0.054 | 18.29 | 9 | 110.54 |

| Parameter learning | 20.80 | 0.024 | 245.64 | 8 | 121.69 |

| SOCR(Extended Comparator Hypothesis) | 32.45 | - | 292.53 | 6 | 127.85 |

| HW-RW(Extended Rescorla-Wagner model) | 67.06 | - | 848.88 | 8 | 155.64 |

Further, we included two advanced associative models that represent modern implementations of the cue competition idea formulated in the original Rescorla-Wagner (RW) model. These extend the RW model to allow for retrospective updating of associations and to capture the covariance information between cues and outcomes. Like the RW model, Van Hamme and Wasserman’s extension7 (Supplementary Fig. 10d) implements cue competition during learning, but also updates associations when either the cue or the outcome (or both) are absent. Although this model utilizes the covariance information between a cue and an outcome, it evaluates these cue-outcome correlations in isolation for each cue, and as such did not give a good account of the behavior we observed (Table 1). A further shortcoming of this model is that it cannot account for the hippocampal interventions, since it doesn’t predict contingency degradation in the absence of a competing variable (c.f. Fig. 2b,c). We therefore also evaluated a version of this model where we added the Background cue, however this modification didn’t result in a significantly better model fit (Supplementary Table 1). The sometimes competing retrieval model8 (SOCR) considers the covariance information both between cues and outcomes and between different cues, in this sense approximating the principles of a Bayesian parameter learning model, and implements cue competition at the time of memory retrieval. We fit this model to the behavioral data both in its original form, and with the added Background variable, but it did not provide a comparable fit to SLM (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1).

SLM thus provided a better quantitative fit than PLM or associative cue-competition models, while also using fewer free parameters, and was robust to changes in specific components of the model (Supplementary Table 2), suggesting that it is the principle of evaluating different models of the environment that enables it to match observed behavior.

A model implementing full Bayesian inference by learning both a distribution over structures and corresponding parameters (SPLM) provided a similar fit to SLM (Supplementary Fig. 10b), but performed worse according to measures controlling for extra model parameters (Table 1) with Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), indicating that improvements from adding parameter learning did not justify adding even a single parameter to the model.

Discussion

Here we examined the neural and computational processes through which ambiguity regulates aversive memory strength. First, we identified key neural processes regulating contingency learning, revealing a novel function of amygdala pyramidal neurons: in addition to their known role in storing associative aversive memories, they also actively participate in regulating a given association in response to signals (unsignaled aversive outcomes) that increase ambiguity in the cue-outcome association. Further, our results demonstrate that the degree of enhancement of auditory CS processing in amygdala neurons directly reflects a given CS-US contingency. Finally, we found converging evidence on the computational and implementation levels against learning models that rely only on learning competing cue-outcome associations, supporting instead an account that directly assesses ambiguity in the environment’s structure.

Structure and Parameter learning as complementary strategies

When learning from sparse and ambiguous data, structure learning and model selection are important prerequisites for making successful predictions. Falsely assuming predictive relationships where they don’t exist leads to a form of overfitting30 and to poor generalization for future predictions. Quickly distinguishing spurious and predictive relationships is therefore important, and structure learning achieves this by also considering sparser structures that might lead to better predictions by identifying which variables actually interact.

While the exact contingencies between variables (e.g. the strength of a generative causal process) often change over time, the existence or lack of a predictive relationship tends to be a stable property of an environment over time. This provides a strong rationale for separating the structure and parameter aspects of learning in certain domains, and for engaging a structure learning mechanism when the brain is initially faced with a new environment or task.

Once enough information is gathered to evaluate different structures with a certain confidence, an important next step is to fine-tune the individual parameters of those models. We theorize that as animals explore their environment, initial learning is geared towards structure learning, with a (potentially gradual) switch to parameter learning following suit, resulting in distributed representations of associations Since continually updating a distribution over structures is computationally expensive and likely inadvisable, structure might be reengaged only if new environmental variables are encountered or the events in the environment strongly violate expectations based on the current model. Such a dual learning mechanism could in turn help explain the difficulty of persistently weakening aversive memories, and account for some important phenomena in memory updating and reconsolidation31.

Brain structures such as the medial prefrontal cortex or the anterior cingulate have been indicated in updating or representing internal models of the environment32,33. These brain regions together with the amygdala24,34, as well as certain neuromodulators35, could help determine which type of learning is employed, depending on the level of ambiguity in the environmental contingencies, and on how rapidly or drastically these contingencies appear to change. A more exact understanding of the circumstances that engage the different learning strategies would be important in understanding how aversive memories are updated, with possible clinical applications in the treatment of persistent and/or exaggerated responses.

Context as both cue and modulator for internal models

Here we examined the conditioning context’s role as a CS, however the context is also known to have important effects on learning that go beyond forming predictive associations, by modulating memory retrieval. While first-learned associations often easily transfer between (physical or temporal) contexts for retrieval36, if learning that takes place over multiple epochs or in multiple contexts, behavior can be sensitive to the retrieval context as well. Thus it is possible that in complex paradigms different distributions over structures get associated with different environments, or a change of context determines whether structure or parameter learning is preferentially engaged, which could explain the context’s role as a modulator of memory.

A different formulation of structure learning using latent causes, on which our current work also builds37, proceeds by clustering together similar events in the environment, with subsequent work successfully modeling phenomena related to extinction, and renewal38,39. The context-specific nature of these phenomena in particular could be an important example of how structure learning results in context-specific behaviors. Though these different formulations of structure learning rely on different computational processes, and explain different learning phenomena, they all give support to the idea that the brain could employ structure learning to deal with certain types of uncertainty.

Neural implementation of structure learning

The experimental findings and SLM together suggest a potential novel algorithmic level view on how structure learning and structured representation of the environment could emerge in associative learning, by implying a circuit architecture in which this learning could be implemented. The LA is known to be an important integrative site through which sensory information from different modalities are associated with aversive (or rewarding) outcomes. Current views suggest that plasticity of modality specific sensory input synapses to LA neurons mediates this form of aversive learning. However, cells in the LA and in thalamic and cortical structures that provide sensory input to the LA show a diversity of response properties, with some cells responding to several sensory cues, rather than a single one 40–42. This representation parallels the diversity of graph structures seen in our statistical model, with different combination of cues associated with the US in different graphs.

Several models have been proposed for how neurons might compute inference in graphical models43,44 Some in particular have suggested that simple learning rules can produce synaptic weights and firing rates which represent how well patterns of sensory stimuli in the environment agree with an internal generative model45. A synaptic learning rule tracking the likelihood of a generative model represented by input synapses, together with an appropriately learnt normalization to translate these likelihoods into a probability distribution across the structures could then implement structure learning in SLM. In such an implementation the priors of the model correspond to an initial distribution over synaptic weights and the ratio of cells with different combinations of sensory input. Such a neural representation could provide a simple and efficient probabilistic code for structure learning46. Unlike traditional models of associative learning where a single weight and corresponding synaptic connection(s) controls an association, here information about each association is represented by, and distributed over, multiple weights. An important characteristic of such a distributed representation is that computations can proceed in parallel over different microcircuits representing different models of the environment, but with all of them affecting each other at the time of behavioral readout. Updating multiple graphical structures representing the different features of a given learning environment at amygdala neuron synapses, and/or at synapses in upstream areas, could be accomplished through well-established heterosynaptic plasticity mechanisms47,48 which allow for synaptic weight changes even at synapses which are not directly recruited during plasticity induction.

Explicitly representing the many possible structures of a complex environment can be a challenge, even though calculating the posterior probability over specific features (such as edge probability) can be done efficiently even for a large number of variables under reasonable constraints49 (such as imposed by temporal relationships between cues and the complexity of models considered). However, a synaptic sampling mechanism, where the inherent variability of synapses represents a distribution of synaptic strengths might provide a more efficient alternative to an exact enumeration of graph structures and in particular might implement the integration over many different parameter values through sampling over stochastic synaptic features and spine motility50.

Our electrophysiology data demonstrate that averaged (LFP) neural activity in LA can track contingencies over broad timescales and that activation of LA neurons is important in regulating contingency evaluations during learning. This supports the idea that LA neural activity reflects and can causally modulate inferential processes. While these data suggest that LA (or other) neuronal ensembles can encode sensory information as probabilistic graphical structures, an ideal test of this model is to examine more closely whether neuronal ensembles in these circuits encode information in this way and how learning affects these representations. However, this requires the ability to chronically monitor large-scale neuronal population dynamics. Until recently this has not been possible, but recent advances in neuronal recording and imaging techniques4 may allow researchers to examine when and how these types of representations are encoded and altered with learning. The structure learning model along with the experimental data described here provide a powerful framework for guiding future research in this area. This approach could reveal novel insights into how environmental stimuli are selected to become associated with biological threats, and could be a key step in understanding anxiety disorders that are characterized by maladaptive and inappropriate responses to stimuli.

Online Methods

Subjects

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Hilltop) approximately 8 weeks old and weighing 275–300g (225–250g for the electrophysiology experiments) on arrival were individually housed on a 12h light/dark cycle and given food and water ad libitum. All animals were naive and had no previous history prior to the conditioning experiment or surgery appropriate to their group. All procedures were approved by the New York University Animal Care and Use Committee, and the Animal Care and Use Committees of the RIKEN Brain Science Institute, and conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals.

Viral Vectors

Lentiviral vectors (lentivirus-CaMKII-ArchT-GFP) were produced by, and purchased from the University of North Carolina Vector Core. Previous work21 has demonstrated specific expression in LA pyramidal neurons using these vectors.

Behavioral conditioning experiments

Animals were placed into a custom-modified Med Associates sound-isolating chamber with plexiglass walls, illuminated only by infra-red light, and underwent one of several conditioning protocols consisting of sequences of CS-US pairings and/or unsignaled USs (UUSs). The CS for all experiments was a series of 5kHz tone pips (pips at 1Hz with 250ms on and 750ms off) for 30 seconds. US onset occurred and coterminated with the final pip. The US was a 1 sec, 1 mA footshock. Inter-trial intervals (ITIs) between the USs were randomized around 120 seconds. For the cover stimulus experiment, the light CS was a 30s flashing white light. Animals were removed from the training context 60s after the final US of the conditioning protocol (except for animals that received unreinforced context exposure, which were removed 60s after the end of the last ITI), and spent around 120s in total outside both the conditioning chamber and the behavioral colony (in the room used for conditioning while the conditioning chamber was cleaned, and in transit to and from the behavioral colony). During the long-term Context memory testing phase 24h later, animals were placed back in the original conditioning context for 330s. During long-term CS memory testing animals were placed in a novel, peppermint-scented testing chamber (Context B, Coulbourn Instruments), that was different from the conditioning chamber in shape and size, was illuminated by a visible houselight, and had a smooth plastic floor. After a 150s acclimation period, animals were presented with the identical CS five times, with a randomized ITI of around 120s. During the training and testing phases the animals’ behavior was recorded on DVD or on a digital storage unit. A rater who was blind with respect to the treatment group scored the animals’ behavioral freezing during the first 5min of the Context test and during the 5 CSs, as well as the 2 minutes before the first CS in the CS test. Scoring was done offline using a digital stopwatch, and freezing was defined as the cessation of all bodily movement with the exception of respiration-related movement. Percentages were calculated as the ratio of time spent freezing to the total time of 300s for the Context memory test, and to the combined 150s duration of the 5 CSs for the CS memory test. Animals that froze for more than 18s (15%) of the 2 minutes prior to the onset of the first test CS in the novel testing environment of the CS test were excluded from the study, as this freezing interfered with our ability to evaluate the level of the CS memory. The remaining animals showed very low levels of pre-CS freezing (with a mean< 1%). Sample sizes for the different conditioning protocols used for the modeling study are summarized in Supplementary Table 3. Eleven animals only received the CS test, but no Context test, as noted in Supplementary Table 3. These animals were included in the modeling study, but not in the analysis of Experiment 1. As the order of the Context and CS tests had no statistically significant effect on freezing (Supplementary Table 4), Context testing was always done first for behavioral experiments with surgerized animals. All conditioning and testing was done during the light cycle.

Randomization

Animals were randomly assigned to experimental groups before the start of each experiment. Experiments were blocked so that groups alternated and the first group for each day was randomly selected. ITIs were pseudorandom around 2min.

Stereotaxic cannula implantation, virus injection, and electrode surgery

Animals were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine/xylazine, surgerized and implanted with bilateral chronic guide cannulae (22 gauge, Plastics One) above the DH (stereotaxic coordinates from Bregma anterior-posterior: −3.8 mm, dorsal-ventral: −2.6 mm, medial-lateral: 1.5 mm) or the LA (21 gauge, stereotaxic coordinates from Bregma anterior-posterior: −3.0 mm, dorsal-ventral: −6.6 mm, medial-lateral: 5.4 mm). For optogenetic experiments simultaneous bilateral injections of 0.5ul lentivirus were made following cannula placement, through an injector cannula on each side (26 gauge, Plastics One) that protruded 1.4mm beyond the tip of the guide cannula, and was attached to a 1µl Hamilton syringe (gauge 25s) by polyethylene tubing. Injections were controlled by an automatic pump (PHD 2000, Harvard Apparatus) and were made at a rate of 0.07 µl/min. Injector cannulae were left in place for 20 min post injection and then replaced with clean dummy cannulae.

For awake, behaving electrophysiological experiments, animals were anesthetized as above, and an insulated stainless steel recording wire (1–2MΩ) (FHC, Inc) , attached to a circuit board (Pentalogix) was lowered such that the tip of the electrode targeted the left LA ( stereotaxic coordinates from Bregma, anterior-posterior: −3.0 mm, dorsal-ventral: −8.0 mm, medial-lateral: 5.4 mm). Additionally, two silver wires, one placed contralaterally and one ipsilaterally above the neocortex served as a reference and ground respectively. For all experiments, guides and electrode boards were affixed to the skull using surgical screws and dental cement.

Awake-behaving psychopharmacology experiments

Approximately one week after DH cannula surgery the competitive NMDA receptor antagonist APV (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in saline at a concentration of 10µg/ µl. Animals were taken one-by-one and injection guides (28 gauge), connected to 1µl Hamilton syringes (gauge 25s) mounted onto an automatic pump (PHD 2000, Harvard Apparatus) were inserted through the implanted cannulae, such that they extended 1mm below tip of the cannulae. After the injectors were in place, rats received bilateral infusions of ether 0.5µl saline or 0.5µ of the 10µg/µl APV-saline solution (5µg APV per hemisphere), at a rate of 0.1µl per minute, for 5min. The injectors were left in place for 4min after the infusion was completed, and replaced with clean dummy cannulae. Animals were returned to the animal colony for 6min, after which time the conditioning session began. Conditioning and testing were conducted as described in the Behavioral conditioning experiments session.

Awake-behaving optogenetic experiments

Approximately 4 weeks after virus infusion, a fibre optic cable attached to a 532 nm diode pumped solid state laser (Shanghai Laser and Optics Century Co, Ltd) was inserted through, and screwed onto each of the bilateral cannulae targeting the LA, such that the tip of the fiber optic cable extended 1 mm beyond the tip of the cannula. The tubing surrounding the fibre optic cables was painted black, so that the laser illumination caused no perceptible illumination of the conditioning chamber. Rats with the fibre optic cables attached then underwent conditioning as described in the Behavioral conditioning experiments section, except that they received laser illumination either occurring 250 ms prior to UUS onset and lasting 50 ms after UUS termination (‘Overlap’ group), or an identical laser illumination delayed after the UUS by a random time interval of around 30s (‘Offset’ group). The fiber optic cables were also attached to the cannulae prior to the Context test, but no laser illumination was given.

Awake-behaving local field potential physiology

During the first two consecutive days of the awake-behaving physiology experiments, animals were taken one-by one, attached to the electrophysiological setup, and placed in a novel, peppermint-scented testing chamber conditioning chamber (Context C) that was distinct from Context A (and Context B) in shape and size, illuminated by a visible houselight, with metal bar walls and a plastic floor. After a 5min acclimation period, animals were habituated with 3 presentations of the CS (with the same CS as described in the Behavioral conditioning experiments section) with a randomized ITI of between 1 and 5min. LA local field potentials were recorded during these two sessions. The third day all rats were conditioned as previously described in the behavioral conditioning experiments method section. 24 hours after conditioning rats were placed back in Context C, and after 5 minutes acclimation 5 CSs were delivered with a random ITI of between 90s and 150s, while LA local field potentials and freezing behavior were recorded. CS presentation was automated using Spike2 software (CED, Cambridge UK). Electrical signals were recorded and analyzed as described previously21. Latencies of the A-LFP and the average waveform amplitudes during habituation for the two groups are given in Supplementary Table 5. Statistical comparisons were made using two-tailed unpaired t-tests, and two-way ANOVA for the latencies.

Single unit physiology

For single unit electrophysiological studies, rats received chronically implanted driveable microdrives consisting of 16 stereotrode bundles (0.001-inch insulated tungsten wire (Ø=25µm), California Fine Wire Company) and eyelid wires for shock delivery51. Following recovery from surgery, daily screening sessions were conducted until single, shock responsive units were isolated (testing was done using mild, single pulse (2 ms) 1 mA eyelid shocks). Animals then received intermixed shocks (12 trials of each condition) alone (2 ms, 2 mA at 7 Hz for 1 sec) or shocks with laser illumination (589 nm, Shanghai `Laser Company). Laser onset occurred 400 ms prior to shocks and was turned off 50 ms after US termination. Spike data were acquired using a Neuralynx data acquisition system. Spike clustering and single unit isolation were performed using Neuralynx SpikeSort 3D software and spiking data. Single unit isolation was assumed if spike trains had a refractory period of greater than 1 ms and a mean spike amplitude of at least 70 µV.

Histology

After behavioral testing was completed, animals were anesthetized with an overdose of chloral hydrate and perfused with paraformaldehyde (for optogenetic experiments) or with either 10% buffered formalin or Prefer. For animals with electrode implants, the location of the electrode was marked by passing a small current (4 µA; 5 s) through the electrode tips prior to perfusion. Following perfusions, brains were sectioned into 40 µm coronal slices and stained with Nissl (Sigma-aldrich, C5042, staining only for animals with electrode implants or hippocampal cannulation). An experimenter blind to the identity of the animal and treatment assessed the placement of the cannulae, electrodes and virus expression. For animals to be included in the analysis of the optogenetic experiment, Arch-T had to be expressed in LA neurons, with the tip of the each guide cannula dorsal and proximal to the LA (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Statistical analysis

Experiments 1–3 had a two-way design and were analyzed accordingly with a two-way ANOVA model with interaction. CS and Context scores were analyzed separately. Experiment 4 was analyzed using unpaired t-tests. We tested for normality using a Lilliefors test with a critical value of 0.01, and for equality of variances in experiments 1–3 using Levene’s test. The groups compared were found to be normally distributed with equal variances, with two exceptions. The Lilliefors test was significant for the context test scores for CTL II group in experiment 1. However, given the large sample size (n = 22) in this experiment, and the strong negative result (p > 0.8) for a difference between CTL II and Pairings First groups, the result of the ANOVA test can be expected to be robust to this violation. Levene’s test found unequal variances among the context test scores in experiment 2, since the scores from the APV groups tended to lie very close to 0, resulting in a small variance. We used the “Keppel” correction to correct for this violation by substituting α/2 for the original critical value α = 0.05. Since our p-value was very small (p = 0.0043), changing the critical value had no effect on the test’s conclusion and our result is expected to be robust against this violation. We also found unequal variances using the two-sampled F test for both freezing scores and amplitude changes in experiment 4, and accordingly used an unpaired two sample t test with unequal variances. Since repeated measures ANOVAs can be especially susceptible to violations in sphericity, we used a lower bound correction when sphericity was violated (Supplementary Fig. 2 and 7).

F and p values for interaction and main effects, as well as for simple effects, are summarized in Supplementary Table 6. For simple effects we report the individual p values, as adjusting for multiple comparison by the Holm-Sidak procedure did not affect statistical significance. We also used a two-way ANOVA to evaluate the effect of the order of the Context and CS tests, for data from experiment 1, as well as using data from all the behavioral experiments where the order of testing was varied (Supplementary Table 4). We measured the effect size of contingency on CS memory in experiment 1, and performed power analysis to determine an appropriate range of sample sizes for the subsequent experiments. The effect size of f = 0.31 fell in the medium (0.25) to high (0.40) range for this type of test, with a power of 0.78. We set the target sample size for experiments 2 and 3 to detect a strong effect (f = 0.4) with a power of at least 0.6, requiring a total n of at least 33. The t test comparing changes in LFP amplitudes in experiment 3 had an effect size of 1.15.

To compare means of discrete measures, such as defecation (Supplementary Fig. 3), we used the Mann-Whitney U test. All tests used in this study were two-tailed. Mean and standard error values for our data are listed in Supplementary Table 7.

A supplementary Reporting and Methods checklist is available

Bayesian Network models

The Bayesian network models represented the environment with graphs over four binary variables, the Background, Context, CS (tone) and US. For notational simplicity we’ll also refer to these as X1,X2,X3 and X4 respectively, or as the vector of variables X, with each taking either the value 0 (absent) or 1 (present). For each training protocol, a series of observations Xt was summarized into counts of the eight different configurations of the four binary variables (eight rather than sixteen, since the Background, by definition, will always be ‘present’ during the experiment). We adopted the use of the Background variable from causal learning models, to represent the sum of all unobservable or unspecified influences on our system (in particular on the US occurrence). As such, the Background will always be present during learning, but absent for predictions during recall, and an edge from the Background to the US (X1 → X4) present in all graphs. An alternative to having the Background variable is to specify an (e.g beta) prior distribution for the probability of US occurrence for the case when the US has no parent variables, or when all of its parent variables are absent, allowing one to calculate likelihoods of observations. This can yield to a similar fit as the original SLM, but the Background variable from the PLM is highly detrimental to its fit. (see Supplementary Information and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 and further discussion).

We considered potential edges that conform with the ordering Xi < Xj iff i < j: between the Context and the US X2 → X4, the Tone and the US X3 → US and between the Context and the Tone X2 → X3, with corresponding parameters ω1,4, ω2,4, ω3,4 and ω2,3, respectively. We assumed that the animals learn this ordering because , of the temporal order and duration of the stimuli. Edges between variables represented noisy-or generating functions, corresponding to the assumption that different parent variables predict a child variable independently (analogous to independent generative causes, but without making assumptions about causality). For edges with parameters 0 ≤ ωi,j ≤ 1, the relevant probabilities are then given by

| (1) |

and

| (2) |

with uniform U[0,1] priors for

Pa(X) is the parent set of X (all the variables sending edges to X). More details about the temporal representation of trials and about the assumptions of the model about the stationary nature of the environment in the Supplementary Information.

Structure learning (SLM)

For SLM we calculated the posterior distribution over different Bayesian network structures, without assuming or learning specific parameter values ωi for the edges. We considered the six possible graph structures Gi ∈ G that can lead to different predictions about the US (Fig. 5a). In Graphs 1 and 2, leaving out, or adding the edge X2 → X3 is irrelevant when making predictions about the US, we therefore considered only one of each of these pairs of functionally equivalent graphs ( the one with no X2 → X3 edge)

By Bayes’ rule

| (4) |

so to calculate the posterior probability of a graph structure G, we integrated out the parameters in the graph, assuming that each comes, independently, from the uniform distribution U[0,1]. We fitted a prior P(G1) = ρ for the minimally connected graph G1, to account for the fact that the Cs and the Context are initially largely neutral stimuli that don’t predict threats. The other graphs had equal priors . Unlike parameter priors, which strongly influence structure learning no matter the amount of data, the effect of these structure priors on the predictions of the model becomes less important as the number of training trials increases (i.e. as the data overwhelmed the priors).

The likelihood term for a graph Gi is the probability of observing a particular combination of stimuli during a complete training protocol, given a graph structure G and parameters ω|Gi (for the edges present in Gi). To calculate this probability, we took the product over the sequence of observations xt so that

| (5) |

T here is the total number of time bins during the experiment, including the time outside the training context, and the sum of fragmented bins as described above. (For notational simplicity we chose to write the integral as integrating over a sequence of trials, rather than counts of a specific trial type, but the two approaches are of course equivalent).

To calculate the posterior probability of a feature f, such as particular edge, or a path, we used model averaging over the graph structures

| (6) |

where f(G) is 0 or 1, depending on whether the feature f is in graph G or not. Such model averaging is a popular tool for prediction problems when limited data means that the posterior distribution over graphs is not peaked at a single structure (i.e. the choice of a single structure for predictions is inappropriate).

The behavioral response to the tone CS is then predicted to be proportionate to the posterior probability of the edge X3→X4:

The context can be connected to the US both by a direct edge X2 → X4 and indirectly through the path X2 → X3 → X4. In cases where a direct connection doesn’t exist, an indirect connection still signifies statistical dependency in cases when the intermediate variable(s) cannot be observed (i.e. an unconditional dependency). Such a connection can therefore serve as a basis for a (possibly weaker) behavioral response. Such a weaker response has been reported observed in many studies in the form of second-order conditioning, or facilitation. Such a relationship could be represented in the brain by disynaptic or polysynaptic connections, resulting in a weaker feedforward response. We therefore introduced a second model parameter α, 0 ≤ α ≤ 1 that reflects a discounting factor for such secondary relationships, as well as weighing this indirect context-US relationship by a simple estimate of the Context-CS association, depending on the frequency the CS appeared in the Context, .

where , for some constant α.

This parameter could also potentially account for influences of temporal discounting, as well as substituting for the need to specify a non-uniform prior distribution for the CS-on probability.

For training protocols where no tone was played, the posterior is calculated only over two structures with the variables X1, X2 and X4. Here P (Gi|D)∝

| (7) |

where P (G) is a uniform prior. In this case we have

Since the integrals in (5) and (6) cannot be evaluated analytically when any variable has two or more parents, we used a Monte Carlo stimulation to approximate their value. For each calculation, 2.5 * 105 samples of the parameter vector ω were drawn from a uniform distribution, and the resulting likelihoods averaged over. For given parameters P1 and α this gave predicted behavioral responses for all the different training protocols.

Parameter learning (PLM)

PLM predicts behavioral responses based on learning the posterior mean of the parameter values in the maximally connected graph, Graph 6 (Fig. 5a). For parameter ωj,k (for the edge Xi → Xj) using the joint prior over ω, we have

| (8) |

Predictions are based on standard inference in the network with parameters ω̂ such that

Each of the four Bayesian network parameters, ωj,k has an independent beta prior distribution. Fitting the model thus includes finding a pair of parameters for each of these four prior beta distributions (8 parameters in total), such that they best explain the behavioral data across all training protocols. We carried out this optimization using a genetic algorithm separately for different discretization parameters t that determined the temporal subdivision of the 2 minute trials. We allowed some flexibility towards the discretization of the CS in form of a binary choice when t does not uniquely determine the discretization of the CS. (E.g. when t=5 the CS could be both length two or length one). We found that the default discretization of t=1 provided a considerably better fit than all other values of t.

Learning both structure and parameters (PSLM)

Learning a full posterior over the Bayesian network representations includes first learning a distribution over the graph structures as in 2.1.4, and then learning a posterior distribution for the parameters present for each structure. Predictions are then made by averaging over predictions from the different graph structures weighed by the posterior probability of each graph.

where for notational simplicity we take if the corresponding edge is not present in graph Gi. We assumed a prior over the relevant graph structures as in 2.1.4, with ρ a free parameter, uniform priors for parameters for structure learning, and fitted Beta priors for the parameter learning as in 1.1.2, such that these Beta priors were shared across all graph structures where the respective parameters were present. Accordingly, this model fits nine parameters.

Model fitting

Since our data has two distinct measures (CS freezing and context freezing) we used mean squared error (MSE) rather than R-squared as a measure of model fit. To evaluate the fit of the model, predicted responses were scaled to freezing scores by multiplication with a scaling factor found by linear regression. This was done separately for the context and for the CS freezing scores, since the different behavioral testing procedures are likely to result in different scaling factors. Mean squared error (MSE) was then calculated by summing these squared error terms and dividing by 29, the number of different conditioning protocols. The best fitting parameters were found using a genetic algorithm, using MATLAB’s ga function. Parameters for the Beta priors were constrained to lie between 0.01 and 30. For each model, we repeated the optimization process at least ten times, with each run giving approximately the same minimum error values. Values for α and P(G1) for SLM (and SPLM) were also consistent across runs, but the best-fit Beta parameters varied, since different pairs of Beta parameters can determine very similar distributions. For each model, we then averaged over twenty runs with each of the 50 best-fitting set of parameters found during the optimization process, and chose the set of parameters which gave the smallest average error (Supplementary Table 1). For each model, we checked the feasibility of this optimization by generating a dataset from the model using four sets of randomly generated parameters. These four datasets per model were scaled so that the means of the CS and context scores matched the means from the behavioral data (so that MSEs could be appropriately compared). Fitting these generated datasets by the procedure outlined above (but running the genetic algorithm only once rather then 10 times), we 2 obtained MSEs that were all below 0.05 %2. Best-fit parameters for the models are listed in Supplementary Table 8.

Modeling neural interventions

The inactivation of the hippocampus during learning was modeled using the best-fit parameters from the behavioral data, and removing the variable X2 and the corresponding edges from the model (or equivalently, by setting the prior for all these edges to the delta function), and calculating the predicted CS-elicited freezing scores. Amygdala inactivation during the US was modeled by excluding trials with inactivation from the trial counts (such that they counted neither towards the reinforced, nor the unreinforced trials).

Code availability

All MATLAB (R2014b) scripts used to fit and compare the computational models are available upon request.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Gardner, W.J. Ma and C. Yokoyama for advice and comments on the manuscript and N. Daw for helpful discussions during the course of this work. We thank the UNC vector core and E. Boyden (MIT) for the lentiviral vectors. This study was funded by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grants R01-MH046516 and R01-MH38774, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) grant DA029053 (J.E.L.), MEXT Strategic Research Program for Brain Sciences (11041047) and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (25710003, 25116531, 15H04264, 16H01291) grants (J.P.J.), and NYU Williamson Fellowship (T.J.M)

Footnotes

Note: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Author Contributions T.J.M designed the experiments, collected and analyzed data, developed the computational models and wrote the manuscript. J.P.J designed the experiments, collected data and wrote the manuscript. L.D.M collected and analyzed electrophysiology data. O.A. collected data. E.A.Y. collected and analyzed single cell electrophysiology data. J.E.L. contributed to data interpretation and the final version of the manuscript.

Competing Financial Interests Statement The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Maren S, Quirk GJ. Neuronal signalling of fear memory. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;5:844–852. doi: 10.1038/nrn1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.LeDoux JE. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2000;23:155–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herry C, Johansen JP. Encoding of fear learning and memory in distributed neuronal circuits. Nat. Neurosci. 2014;17:1644–1654. doi: 10.1038/nn.3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gründemann J, Lüthi A. Ensemble coding in amygdala circuits for associative learning. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2015;35:200–6. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rescorla Ra. Probability of shock in the presence and absence of CS in fear conditioning. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1968;66:1–5. doi: 10.1037/h0025984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rescorla RA, Wagner AR. Classical Conditioning II Current Research and Theory. 1972;21:64–99. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Hamme LJ, Wasserman EA. Cue Competition in Causality Judgments: The Role of Nonpresentation of Compound Stimulus Elements. Learn. Motiv. 1994;25:127–151. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stout SC, Miller RR. Sometimes-competing retrieval (SOCR): a formalization of the comparator hypothesis. Psychol. Rev. 2007;114:759–783. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.114.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pearce JM, Bouton ME. Theories of associative learning in animals. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001;52:111–139. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamin LJ. Attention-like” Processes In Classical Condiioning. Miami Symposium On The Production Of Behavior Aversive Stimulation. 1968:9–33. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauer EP, LeDoux JE, Nader K. Fear conditioning and LTP in the lateral amygdala are sensitive to the same stimulus contingencies. Nat. Neurosci. 2001;4:687–688. doi: 10.1038/89465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holyoak KJ, Cheng PW. Causal learning and inference as a rational process: the new synthesis. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2011;62:135–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JJ, DeCola JP, Landeira-Fernandez J, Fanselow MS. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist APV blocks acquisition but not expression of fear conditioning. Behav. Neurosci. 1991;105:126–133. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.105.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNish KA, Gewirtz JC, Davis M. Disruption of contextual freezing, but not contextual blocking of fear-potentiated startle, after lesions of the dorsal hippocampus. Behav. Neurosci. 2000;114:64–76. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durlach PJ. Effect of signaling intertrial unconditioned stimuli in autoshaping. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Process. 1983;9:374–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gunther LM, Miller RR. Prevention of the degraded-contingency effect by signalling training trials. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. B. 2000;53:97–119. doi: 10.1080/713932719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balleine BW, Killcross AS, Dickinson A. The effect of lesions of the basolateral amygdala on instrumental conditioning. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:666–75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00666.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bermudez Ma, Schultz W. Responses of amygdala neurons to positive reward-predicting stimuli depend on background reward (contingency) rather than stimulus-reward pairing (contiguity) J. Neurophysiol. 2010;103:1158–1170. doi: 10.1152/jn.00933.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogan MT, Stäubli UV, LeDoux JE. Fear conditioning induces associative long-term potentiation in the amygdala [see comments] [published erratum appears in Nature 1998 Feb 19;391(6669):818] Nature. 1997;390:604–607. doi: 10.1038/37601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chow BY, et al. High-performance genetically targetable optical neural silencing by light-driven proton pumps. Nature. 2010;463:98–102. doi: 10.1038/nature08652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johansen JP, et al. Hebbian and neuromodulatory mechanisms interact to trigger associative memory formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014;111:201421304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421304111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goosens KA, Hobin JA, Maren S. Auditory-Evoked Spike Firing in the Lateral Amygdala and Pavlovian Fear Conditioning. Neuron. 2003;40:1013–1022. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00728-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prévost C, McNamee D, Jessup RK, Bossaerts P, O’Doherty JP. Evidence for Model-based Computations in the Human Amygdala during Pavlovian Conditioning. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saez A, Rigotti M, Ostojic S, Fusi S, Salzman CD. Abstract Context Representations in Primate Amygdala and Prefrontal Cortex. Neuron. 2015;87:869–881. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pearl J. Probabilistic Reasoning in Intelligent Systems. Vol. 88. Morgan Kauffmann; San Mateo: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffiths TL, Tenenbaum JB. Structure and strength in causal induction. Cogn. Psychol. 2005;51:334–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall G, Symonds M. Overshadowing and latent inhibition of context aversion conditioning in the rat. Auton. Neurosci. Basic Clin. 2006;129:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Witnauer JE, Miller RR. Degraded contingency revisited: posttraining extinction of a cover stimulus attenuates a target cue’s behavioral control. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Process. 2007;33:440–450. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.33.4.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matzel LD, Schachtman TR, Miller RR. Recovery of an overshadowed association achieved by extinction of the overshadowing stimulus. Learning and Motivation. 1985;16:398–412. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koller D, Friedman N. Probabilistic Graphical Models: Principles and Techniques. Vol. 2009. Foundations; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quirk GJ, et al. Erasing fear memories with extinction training. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:14993–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4268-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karlsson MP, Tervo DGR, Karpova AY. Network resets in medial prefrontal cortex mark the onset of behavioral uncertainty. Science. 2012;338:135–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1226518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Behrens TEJ, Woolrich MW, Walton ME, Rushworth MFS. Learning the value of information in an uncertain world. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:1214–1221. doi: 10.1038/nn1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Likhtik E, Paz R. Amygdala-prefrontal interactions in (mal)adaptive learning. Trends Neurosci. 2015;38:158–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu AJ, Dayan P. Uncertainty, neuromodulation, and attention. Neuron. 2005;46:681–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosas JM, Todd TP, Bouton ME. Context Change and Associative Learning. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 2013;4:237–244. doi: 10.1002/wcs.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Courville A, Daw ND, Gordon G, Touretzky DS. Advances in Neural Information Processing. 2004;16 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gershman SJ, Blei DM, Niv Y. Context, learning, and extinction. Psychol. Rev. 2010;117:197–209. doi: 10.1037/a0017808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soto Fa, Gershman SJ, Niv Y. Explaining compound generalization in associative and causal learning through rational principles of dimensional generalization. Psychol. Rev. 2014;121:526–58. doi: 10.1037/a0037018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uwano T, Nishijo H, Ono T, Tamura R. Neuronal responsiveness to various sensory stimuli, and associative learning in the rat amygdala. Neuroscience. 1995;68:339–361. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Romanski LM, Clugnet MC, Bordi F, LeDoux JE. Somatosensory and auditory convergence in the lateral nucleus of the amygdala. Behav. Neurosci. 1993;107:444–450. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.3.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weinberger NM. Auditory associative memory and representational plasticity in the primary auditory cortex. Hear. Res. 2007;229:54–68. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pecevski D, Buesing L, Maass W. Probabilistic inference in general graphical models through sampling in stochastic networks of spiking neurons. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lochmann T, Deneve S. Neural processing as causal inference. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2011;21:774–781. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nessler B, Pfeiffer M, Buesing L, Maass W. Bayesian Computation Emerges in Generic Cortical Microcircuits through Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pouget A, Beck JM, Ma WJ, Latham PE. Probabilistic brains: knowns and unknowns. Nat. Neurosci. 2013;16:1170–8. doi: 10.1038/nn.3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chistiakova M, Bannon NM, Bazhenov M, Volgushev M. Heterosynaptic plasticity: multiple mechanisms and multiple roles. Neuroscientist. 2014;20:483–98. doi: 10.1177/1073858414529829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abraham WC. How long will long-term potentiation last? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2003;358:735–44. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Friedman N, Koller D. Being Bayesian about network structure. A Bayesian approach to structure discovery in Bayesian networks. Mach. Learn. 2003;50:95–125. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kappel D, Habenschuss S, Legenstein R, Maass W. Network Plasticity as Bayesian Inference. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2015;11:e1004485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johansen JP, Tarpley JW, LeDoux JE, Blair HT. Neural substrates for expectation-modulated fear learning in the amygdala and periaqueductal gray. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13:979–986. doi: 10.1038/nn.2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.