Abstract

Background

This case study was undertaken in an effort to assess whether children/adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) experience improvement in comorbid ADHD following Cogmed Working Memory Training (CWMT). This treatment intervention has been shown to improve ADHD symptoms in children and adolescents; however, there have been no studies on its use with individuals with ASD.

Material/Methods

CWMT is a computer-based program that consists of 13 auditory, visual, visual spatial, and combined exercises that are practiced for 45 minutes a day, 5 days a week, for 5 weeks. Fifteen children/adolescents between the ages of 9 and 19 years with ASD and comorbid ADHD undertook a trial of CWMT. A 1-month follow-up and 2 longitudinal follow-ups were implemented.

Results

The retrospective chart analysis and follow-up demonstrated improvement in attention and focus, impulsivity, emotional reactivity, and academic achievement in individuals with ASD and comorbid ADHD. Those benefits remained the same or increased over time. A number of participants also had benefits in their social interaction/social awareness.

Conclusions

CWMT has the potential to be an effective treatment intervention for children and adolescents with ASD because of its benign computer-based nature that seems to engage the unique learning style of this population. The authors hope that this paper will encourage others to study the ability of CWMT to be utilized in improving ADHD symptoms as well as social interaction/social awareness in individuals with ASD.

MeSH Keywords: Autistic Spectrum Disorder, Children, Adolescents, Working Memory

Background

In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (DSM-V), Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is characterized by persistent deficits in communication and interaction, and restrictive, repetitive patterns in behavior, interests, and activities. Individuals with ASD also often have difficulties with distractibility, impulsivity, high activity level, and emotional reactivity. In DSM-IV, these symptoms were subsumed under a diagnosis of Autistic Disorder, while in DSM-V, a diagnosis of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is made separately [1]. Deficits in working memory have been postulated as one of the underlying factors in ADHD [2,3]. Working memory is defined as short-term memory applied to cognitive tasks, as a multi-component system that holds and manipulates information in short-term memory. Essentially, it is the use of attention to manage short-term memory [4]. Cogmed Working Memory Training (CWMT) is a computer program that first demonstrated improvement in ADHD symptoms in the Klingberg et al. study in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in 2004 [5]. Since then, additional studies on the effectiveness of CWMT in treating ADHD symptoms have been performed. Of the studies performed, several support the conclusion reached in the initial Klingberg et al. study, and, while other studies found no evidence of improvement in ADHD symptoms after CWMT, further study of the program was advocated [6, 7].

In October of 2006, our practice began utilizing CWMT on children/adolescents with ADHD. Out of over 400 children/adolescents that have completed the training in our practice, a majority have exhibited improvement in their ADHD symptoms. Despite the fact that individuals with ASD frequently suffer from comorbid ADHD, there have been no published data about the potential of utilizing CWMT for this population. Individuals with ASD are often more sensitive to medication side effects and do not consistently have robust benefits from pharmacologic intervention [8,9]. It was hypothesized that individuals with ASD might respond positively to CWMT, given their clinical presentation, including obsessive-compulsive characteristics and interest in routine and structure. Given this, as well as the very benign nature of this intervention, it appeared reasonable to consider trials of CWMT for ADHD for individuals with ASD.

Material and Methods

The participants chosen for this study were the first 15 children and adolescents with ASD and comorbid ADHD who completed CWMT in our practice from 2007 to 2009. All 15 participants in this study undertook a single trial of CWMT, with the exception of participant #15, who completed a second trial due to an expressed interest in potentially improving benefits. Prior to CWMT, each of the 15 participants in this study initially went through a 3-part child and adolescent psychiatric evaluation. The majority of these individuals had significant comorbidities, as seen in Table 1. For the duration of CWMT and for 1 month after completing CWMT, no changes were made to the participant’s treatment or medication.

Table 1.

Diagnosis of the 15 participants.

| ID | Age | Sex | Diagnosis(es) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12 | M | ASD |

| 2 | 15 | M | ASD with ADHD, OCD |

| 3 | 9 | M | ASD with ADHD, Specific Learning Disabilities |

| 4 | 10 | M | ASD with ADHD |

| 5 | 15 | F | ASD with ADHD, OCD, GAD, Unspecified Depressive Disorder |

| 6 | 14 | M | ASD with ADHD, Tourette’s Syndrome, OCD |

| 7 | 15 | M | ASD with ADHD, OCD, Unspecified Tic Disorder |

| 8 | 16 | M | ASD with ADHD, OCD, Tourette’s Syndrome, Unspecified Depressive Disorder |

| 9 | 11 | M | ASD with ADHD, OCD |

| 10 | 15 | M | ASD with ADHD, Unspecified Depressive Disorder |

| 11 | 15 | F | ASD with ADHD, MDD in Remission, GAD, Panic Disorder without Agorophobia |

| 12 | 9 | M | ASD with ADHD, Tourette’s Syndrome, OCD |

| 13 | 16 | F | ASD with ADHD, Unspecified Anxiety Disorder |

| 14 | 8 | M | ASD with ADHD,OCD, Unspecified Depressive Disorder |

| 15 | 14 | M | ASD with ADHD, OCD |

Before beginning this study, Investigational Review Board approval from Munson Medical Center was requested by the first author and, after review by this committee, the study was exempted. Parents of the individuals who were included in this review expressed an interest in the CWMT treatment intervention. After being provided with information and giving informed consent, a trial of CWMT was undertaken.

CWMT utilizes approximately 13 auditory, visual, and visual spatial or combined exercises done on a daily basis on the computer. The computer program is in the guise of a video game and uses a robot mascot to encourage and coach the participants. The participants spent approximately 45 minutes a day, 5 days a week, for 5 weeks, on the CWMT computer program working their way through multiple intense memory exercises. The simplest example of the 13 exercises required the participant to remember the order of flashing lights on a 4 by 4 grid. The participant then needed to recall the presentation of the variables and enter them into the program in the correct order. When the participant demonstrated that they are able to do this consistently, another variable was added. When the participant made an error, the variables did not decrease to where the participant originally started, but instead either stayed the same or decreased by one variable at a time. The participant’s progressed through the program with a training aide, usually a parent, as well as with a Cogmed-trained coach who spoke with the parent and child at least once per week over the phone. The coach, participant, and training aide, with the appropriate password, were able to log in to Cogmed and view the participant’s progress each day in a user-friendly manner, that is available in the form of understandable graphs.

A retrospective chart analysis of this group, assessed by the first author approximately 1 month after completion of CWMT, was accomplished by averaging parent, child, teacher, and clinician ratings, standardized questionnaires, and continuous performance tests when available. This was done using the definition of improvement in a patient’s comorbid ADHD of 10% to 30% as mild, improvement of 30% to 50% as moderate, and improvement greater than 50% as large. To further assess the potential longitudinal effects of CWMT, a brief questionnaire was mailed out to all participants’ parents in June of 2009 followed by a phone interview 25 months later. Depending on when the participants completed CWMT, the questionnaires and phone interviews were completed anywhere from 4 to 32 months and 29 to 57 months after treatment intervention, respectively.

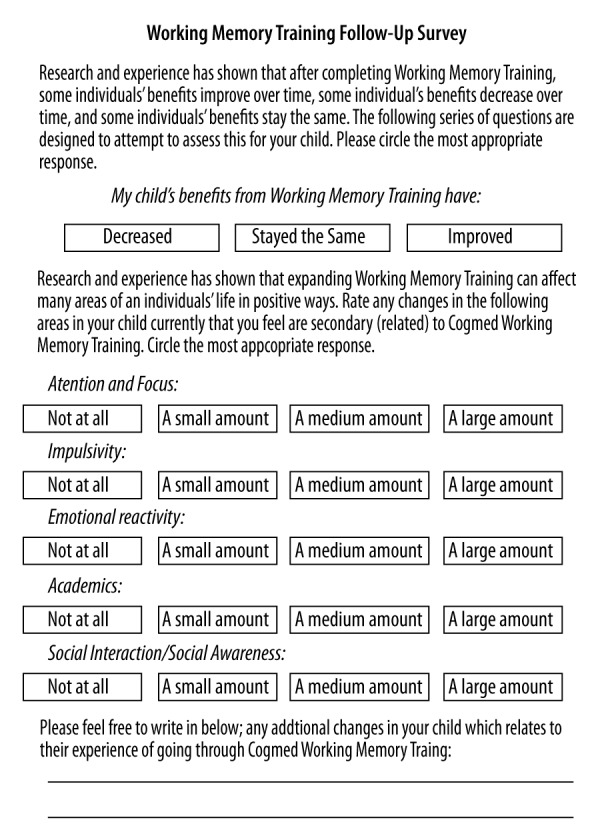

Both the questionnaire and phone interview asked parents to indicate their perspective of how their child’s benefits had changed over time. Specifically, parents were asked to rate their child’s changes in 5 categories that they felt were secondary to CWMT. These included attention and focus, impulsivity, emotional reactivity, and academic achievement. An additional category of social interaction/social awareness was added after some parents spontaneously commented on improvements in this area during the one-month follow-up. Some of the improvements noted included increased eye contact, reciprocal conversation, understanding of nonverbal communication, awareness of personal space and surroundings, and success in relationships. In each of the categories, parents were asked to rate changes as: “not at all,” “a small amount,” “a medium amount,” or “a large amount.” During the phone interview, participants who were now over the age of 18 were also interviewed along with their parents when possible. At the bottom of the questionnaire and at the end of the phone interview, parents and the participants themselves were asked if they had any additional comments (Figure 1). These anecdotal responses were then recorded and collected. For the purposes of this paper, 2 of these 15 participants will be discussed in detail, although data from all 15 participants will be included. Participant #7 and participant #11 will be discussed under the pseudonyms Mark and Tracey.

Figure 1.

Working memory training follow-up survey (questionnaire).

Results

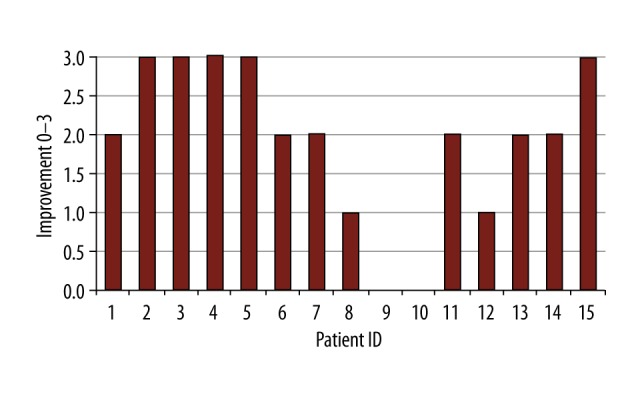

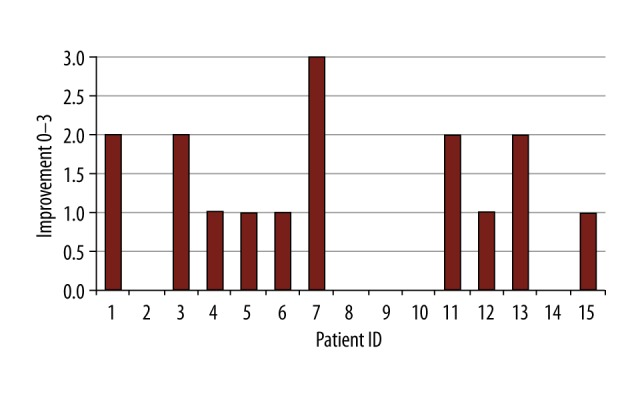

As seen in Figure 2, the retrospective review of the data at one-month post-training demonstrated that of the 15 participants reviewed, 2 showed no change, 4 showed mild improvement, 6 showed moderate improvement, and 3 showed large improvement with their comorbid ADHD. In addition, this retrospective review of the data at one-month post-CWMT revealed that 5 of the individuals who had improvements in their comorbid ADHD also described positive changes in their social interaction/social awareness.

Figure 2.

Pragmatic assessment of benefits at one months post-CWMT.

At 1-month follow-up, Mark’s parents noted that he was more socially confident and aware and was focusing approximately 20% better overall. Mark himself noted an improvement in concentration and focus of 80% and felt positive about the training. One month after completing CWMT, Tracey’s mother noticed that she was more settled and more “functional”. She reported that her daughter had a number of successful social experiences since completing CWMT. Tracey described an improvement of approximately 50% in focus, concentration, and organization since completing CWMT.

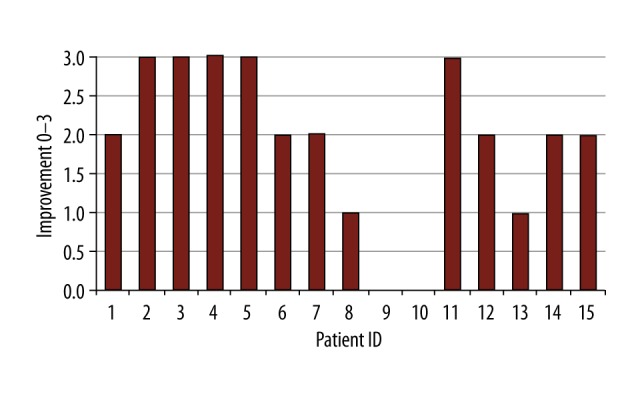

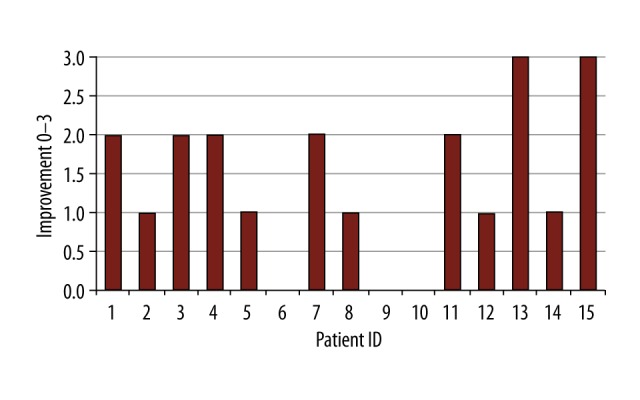

After data from the follow-up questionnaires were collected, it was determined that out of the 15 participants who took part in the case study, 2 had still received no benefits, 1 had experienced a decrease in benefits, 4 had benefits that stayed constant, and 8 had an increase in overall benefits, as shown in Table 2. Figures 3–7 illustrate the findings in each specific area described above, with improvement noted on the X-axis and the consistent patient ID noted on the Y-axis. As illustrated in Figures 3–7, the majority of the participants experienced an increase in benefits in all 5 specific areas of interest, with 11 noting greater success in their social interaction/social awareness. It should be noted that patient #10, whose parent did not return the questionnaire, was included in all of the following graphs as a non-responder to CWMT in all areas. At an appointment, with the first author assessing overall functioning and pharmacologic needs, approximately 6 months after completion of CWMT, his father reported no benefits.

Table 2.

Parent perspective of benefits from CWMT at time of written follow-up questionnaire.

| Patient ID | Result | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Improved over time | Assessed after 31 months |

| 2 | Stayed the same | Assessed after 13 months |

| 3 | Stayed the same | Assessed after 21 months |

| 4 | Improved over time | Assessed after 20 months |

| 5 | Improved over time | Assessed after 21 months |

| 6 | Stayed the same | Assessed after 4 months |

| 7 | Improved over time | Assessed after 11 months |

| 8 | Decreased over time | Assessed after 32 months |

| 9 | Had no benefits initially and had no benefits with follow-up questionnaire after 18 months | |

| 10 | Had no benefits, no follow-up questionnaire | |

| 11 | Improved over time | Assessed after 11 months |

| 12 | Stayed the same | Assessed after 10 months |

| 13 | Improved over time | Assessed after 6 months |

| 14 | Improved over time | Assessed after 5 months |

| 15 | Improved over time | Assessed after 23 months |

Figure 3.

Benefits from CWMT on attention/focus.

Figure 4.

Benefits from CWMT on impulsivity.

Figure 5.

Benefits from CWMT on emotional reactivity.

Figure 6.

Benefits from CWMT on academics.

Figure 7.

Benefits from CWMT on social interaction/awareness.

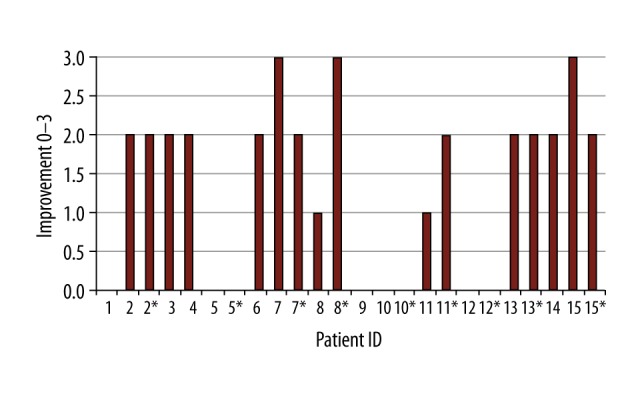

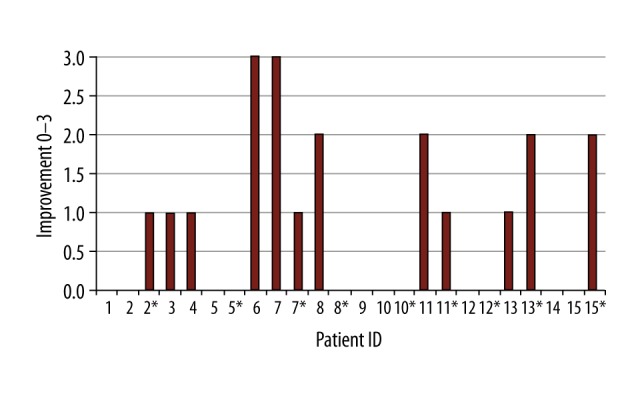

As portrayed in Table 3, of the 13 parents who took part in the phone interview, 9 of them reported that their children’s benefits from CWMT had increased or stayed the same as compared to the second follow-up. All of the participants who were contacted who were over the age of 18 agreed with their parents on this assessment (Figures 8–12).

Table 3.

Parent perspective of benefits from CWMT at phone interview.

| Patient ID | Result | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Decreased over time | Assessed after 56 months |

| 2 | Stayed the same | Assessed after 38 months |

| 3 | Stayed the same | Assessed after 46 months |

| 4 | Improved over time | Assessed after 46 months |

| 5 | Unable to contact | |

| 6 | Stayed the same | Assessed after 29 months |

| 7 | Improved over time | Assessed after 36 months |

| 8 | Decreased over time | Assessed after 57 months |

| 9 | Experienced no benefits | Assessed after 43 months |

| 10 | Experienced no benefits | Assessed after 56 months |

| 11 | Stayed the same | Assessed after 36 months |

| 12 | Unable to contact | |

| 13 | Stayed the same | Assessed after 31 months |

| 14 | Stayed the same | Assessed after 30 months |

| 15 | Improved over time | Assessed after 48 months |

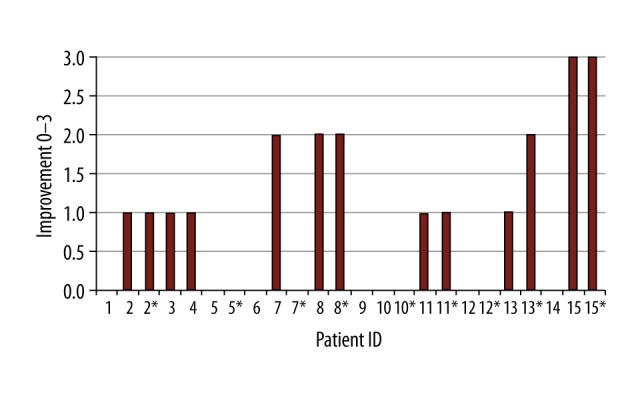

Figure 8.

Benefits from CWMT on attention/focus. Data from 2nd follow-up (phone interview). Any # with an * next to represents the data from participants themselves who are over the age of 18. Any # without an * next to represents the data from the parents of the participants.

Figure 9.

Benefits from CWMT on impulsivity. Data from 2nd follow-up (phone interview). Any # with an * next to represents the data from participants themselves who are over the age of 18. Any # without an * next to represents the data from the parents of the participants.

Figure 10.

Benefits from CWMT to emotional reactivity. Data from 2nd follow-up (phone interview). Any # with an * next to represents the data from participants themselves who are over the age of 18. Any # without an * next to represents the data from the parents of the participants.

Figure 11.

Benefits from CWMT on academic achievement. Data from 2nd follow-up (phone interview). Any # with an * next to represents the data from participants themselves who are over the age of 18. Any # without an * next to represents the data from the parents of the participants.

Figure 12.

Benefits from CWMT on social interaction/awareness. Data from 2nd follow-up (phone interview). Any # with an * next to represents the data from participants themselves who are over the age of 18. Any # without an * next to represents the data from the parents of the participants.

Specifically, in the areas of social interaction/social awareness and attention and focus, 10 of the 15 parents reported that their child/participant were still experiencing benefits. Out of these 10 participants, 5 were over the age of 18 and all 5 described ongoing benefits in their social interaction/social awareness and attention and focus.

Both Mark and Tracey reported that changes in functioning stayed the same or improved since the 1-month follow-up. Mark thought that benefits had stayed the same, but his mother endorsed an improvement. They both noted a moderate to large improvement in Mark’s attention and focus, impulsivity, and social interaction/social awareness. Mark’s mother reported that the most noticeable change in her son’s functioning was in his emotional reactivity; however, Mark only described a minor change in this area. His mother described that Mark was no longer “bent out of shape” when his interaction with others did not go exactly as planned. Also, while Mark noted no change in his academics, his mother believed that it had improved a moderate amount, noting an improvement in his grades in classes he was not interested in.

Tracey, along with her mother, described her benefits as having stayed the same since the last follow-up. Both noted a small to moderate improvement in her attention and focus, impulsivity, emotional reactivity, and academics. While Tracey reported a moderate change in her social interaction/social awareness, her mother thought she had experienced a large change, as she was now calling and receiving calls from peers and making new friends. Tracey’s mother stated that “We have a more connected and more aware daughter”. Tracey described noticing large improvements in her organizational skills, including more successfully keeping her school work “together” and more independently managing her time, which she previously struggled with and which frequently led to significant anxiety. She acknowledged that this appeared to be a long-lasting benefit that had significantly reduced her “stress”.

Discussion

As a whole, it appeared that CWMT, as a treatment intervention utilizing computers, interactive memory challenges, and a consistent structure, along with routine and limited contact with a therapist/coach over the phone, fit well with the characteristics of individuals with ASD. Most of the participants in this study described enjoying the process, and were interested in continuing the exercises at follow-up if possible. Overall, they were motivated to complete the exercises on a daily basis as it fit well into their need for sameness and interest in structure and a consistent routine.

The majority of the 15 participants with ASD experienced improvement in their ADHD symptoms after CWMT. Surprisingly, some parents/participants also noted an improvement in their social interaction/social awareness. Some of these changes included, “appears more mature and aware of his surroundings”, “she seems more confident and happy”, “improved eye contact”, “starting conversations with others more frequently”, “asking me about my day”, “talking with me and not at me”, and “respecting other people’s personal space better”. This information was exciting, as there are many treatment interventions which have been designed to improve social interaction/social awareness for individuals with ASD, yet none have been shown to consistently and significantly benefit impairments. The improvement of all symptoms at 1 month after CWMT was also intriguing, as clinical experience suggests that a significant portion of individuals who complete CWMT do not show substantial benefit until a few months after completion. The data collected from the 2 long-term follow-ups are promising and show that CWMT had continued longitudinal benefits on ADHD symptoms and social interaction/social awareness. Furthermore, the number of participants who experienced this benefit in social interaction/social awareness increased from 5 at the initial 1-month follow-up to 10 at the final phone interview.

There are a number of limitations regarding this retrospective study that are readily acknowledged by the authors, which include: no control group; a small sample size; various comorbidities; and ongoing and varied treatment interventions, including routine medication changes (there were no changes to medications or treatment interventions during CWMT and for 1 month following completion). Also, the follow-up questionnaire and phone interview were designed for the purpose of this study to be simple and concise and had not been used previously in clinical practice or research. Due to the long period of time that had elapsed from the participants’ completion of CWMT to the time of the questionnaire and phone interview, many parents, participants themselves, and the clinicians involved noted difficulty in trying to accurately gauge whether the longer-term benefits that the participant experienced were secondary to CWMT or due to brain maturation, changes in medication, or other treatment interventions.

Conclusions

This retrospective chart analysis and follow-up has been illuminating and has preliminarily demonstrated the effectiveness of CWMT in improving ADHD symptoms as well as social interaction/social awareness in children and adolescents with ASD. CWMT is a benign treatment intervention whose computer-based program is enjoyed by and fits well with the inherent cognitive style of people with ASD. Due to these factors, it is possible that this population may be more responsive to CWMT than those with ADHD alone. It is our hope that these thought-provoking clinical data will motivate clinicians to consider using this non-pharmacological approach and to generate future prospective controlled studies.

Footnotes

Source of support: Departmental sources

Conflicts of interests

None.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington D.C.: APA; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holmes J, Hilton K, Place M, et al. Children with low working memory and children with ADHD: Same or different? Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:976. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kofler M, Alderson M, Raiker J, et al. Working memory and intraindividual variability as neurocognitive indicators in ADHD: Examining competing model predictions. Neuropsychology. 2014;28(3):459–71. doi: 10.1037/neu0000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cowan N. Working memory underpins cognitive development, learning, and education. Educ Psychol Rev. 2014;26(2):197–223. doi: 10.1007/s10648-013-9246-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klingberg T, Fernell E, Olesen P, et al. Computerized training of working memory in children with ADHD – a randomized, controlled, trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(2):177–86. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200502000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steeger C, Gondoli D, Gibson B, Morrissey R. Combined cognitive and parent training interventions for adolescents with ADHD and their mothers: A randomized controlled trial. Child Neuropsychol. 2016;22(4):394–419. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2014.994485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bigorra A, Garolera M, Guijarro, et al. Long-term far-transfer effects of working memory training in children with ADHD: A randomized controlled trial. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;25(8):853–67. doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0804-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeFilippis M, Wagner K. Treatment of autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2016;46(2):18–41. doi: 10.64719/pb.4346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leitner Y. The co-occurrence of autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children— what do we know? Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:268. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]