Abstract

Background

Prelacteal feeding (PLF) is a barrier to exclusive breast feeding.

Objective

To determine factors associated with PLF in rural and urban Nigeria.

Methods

We utilized data from the 2013 Nigerian Demographic and Health Survey. Bivariate and multivariate analyses were used to test for association between PLF and related factors.

Results

Prevalence of PLF in urban Nigeria was 49.8%, while in rural Nigeria it was 66.4%. Sugar or glucose water was given more in urban Nigeria (9.7% vs 2.9%), plain water was given more in rural Nigeria (59.9% vs 40.8%). The multivariate analysis revealed that urban and rural Nigeria shared similarities with respect to factors like mother's education, place of delivery, and size of child at birth being significant predictors of PLF. Mode of delivery and type of birth were significant predictors of PLF only in urban Nigeria, whereas, mother's age at birth was a significant predictor of PLF only in rural Nigeria. Zones also showed variations in the odds of PLF according to place of residence.

Conclusion

Interventions aimed at decreasing PLF rate should be through a tailored approach, and should target at risk sub-groups based on place of residence.

Keywords: Pre-lacteal feeds, mothers, infants, urban, rural, Nigeria

Background

Exclusive breast feeding (EBF) from birth through six months of age has long-term health and emotional benefits for both mother and child and is associated with lower infant morbidity and mortality as well as better growth1. Also, provision of mother's breast milk to infants within one hour of birth ensures that the infant receives colostrum which is rich in immunoglobulin (Ig) and other bioactive molecules important for nutrition, growth and for passive immunity2.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) during the Innocenti Declaration in 1990 called for policies that would cultivate breast feeding culture and encourage women to breastfeed their infants exclusively for the first six months of life3.

Among the 10 steps to successful breast feeding is giving infants no food or drink other than breast milk, unless medically indicated3. Pre-lacteal feeds are foods given to newborns before breast feeding is established or before breast milk comes in4. Studies have shown that introducing these pre-lacteal feeds has the following negative effects; delaying breast feeding initiation, interfering with EBF, disrupting the mother-baby dyad, interfering with suckling, and exposing the baby to risk of infection5–8. In addition, pre-lacteal feeds have fewer nutrients and immunological components as compared to breast milk9.

Nigeria became a fully independent country in October 196010. The population of Nigeria is estimated to be 182 million as of 2015 and the total health expenditure in 2014 was 3.7% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP)11. In Nigeria, neonatal, infant and child mortality as well as malnutrition continue to be major health issues affecting the country10. Nigeria's neonatal mortality rate stands at 37 deaths per 1,000 live births while the infant mortality rate stands at 69 deaths per 1,000 live births10. However, despite these rates, studies have observed that the core indicators of optimal breast feeding in Nigeria are still low with only about 34.7 % of children initiating breast-feeding early and 17.4 % of infants under-five months of age being exclusively breast fed1,12.

Previous literature has shown that the determinant of PLF are multi-factorial in nature and includes factors such as mode of delivery, type of birth, occupation, education, place of delivery, size at birth, and regions5–7,9,13. Studies done in India and Malawi observed rural-urban differences in PLF prevalence with the prevalence of PLF reportedly being higher in rural areas as compared to urban areas14,15.

Breast feeding practices such as Early Initiation of Breast Feeding (EIBF) and EBF are the key and easiest intervention to reducing child death and morbidity1–2. An understanding of factors associated with PLF is important in the promotion of EBF and EIBF. In Nigeria, most previous research with regards to PLF has been based on nationally non-representative samples and these studies have been limited in their ability to compare urban and rural differences in PLF practice. This research fills this gap by examining a nationally representative sample to determine factors associated with PLF in rural and urban residence. This study aims to examine prevalence of PLF, types of pre-lacteal feeds and the determinants of PLF in urban and rural Nigeria. We hypothesized that the factors influencing PLF differ between urban and rural areas in Nigeria.

Methods

Study setting and ethics

This was a cross-sectional study using nationally representative data from the 2013 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) and authorization to use the data was given by Measure DHS. The 2013 NDHS was implemented by the National Population Commission and it is the fifth in the series of Demographic and Health Surveys conducted so far in Nigeria. NDHS have the approval of the National Health Research Ethics Committee.

Administratively, Nigeria is divided into 36 states, and the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja. Each state is sub-divided into local government areas (LGAs), and each LGA is divided into localities.

Sample

The sample for the 2013 NDHS was a stratified sample, selected independently in three stages. Stratification was achieved by separating each state into urban and rural areas. In the first stage, 893 localities were selected with probability proportional to size. In the second stage, one cluster was selected by simple random sampling. In a few larger localities, more than one cluster was selected. In total, 904 clusters (372 in urban areas and 532 in rural areas.) were selected. In the third stage of selection, a fixed number of 45 households were selected in every urban and rural cluster through equal probability systematic sampling.

All women aged 15–49 years who were either permanent residents of the households in the 2013 NDHS sample or visitors present in the households on the night before the survey were eligible to be interviewed. Three sets of validated questionnaires were utilized to collect data and included; a household questionnaire, a woman's questionnaire and a man's questionnaire.

A four-week-long training course in January and February 2013 was conducted for the field staff and the fieldwork was conducted from February 15, 2013, to the end of May (with the exception of the two teams in Kano and Lagos, who completed fieldwork in June).

In the interviewed households, a total of 39,902 women aged 15–49 years (Urban= 15,972 and rural = 23,930 women) were identified as eligible for individual interviews, and 98 percent of them were successfully interviewed10.

Analysis for this study was restricted to last-born ever breastfed children born in the past two years preceeding the survey and the total sample size was 3879 for urban and 7888 for rural residence. After accounting for sample weights, this corresponded to a sample size of 4172 for urban and 7637 for rural areas.

Outcome variable

In the NDHS woman's questionnaire, mothers were asked “In the first three days after delivery, was (NAME) given anything to drink other than breast milk? What was (NAME) given to drink? (Options were: milk (other than breast milk); plain water; sugar or glucose water, gripe water, sugar salt water solution; fruit juice; infant formula; tea infusion; coffee, honey; and/others)10. Our outcome variable pre-lacteal feeding was defined as having given anything to drink other than breast milk in the first three days after delivery. The types of pre-lacteal feeds were reported as frequencies and percentages.

Independent variables

The explanatory factors were chosen based on previous studies5–7,9,13,14 and grouped into two categories namely; maternal socio-demographic factors and antenatal and postnatal factors.

Explanatory variables included the following;

(i) Maternal socio-demographic factors; Ungrouped mothers age at birth was recoded into <=19, 20–24, 25–29, 3034 and >=35 years. Mother's education was categorized as no education, primary, secondary and above. Mother's occupation was re-grouped into not working and working. DHS wealth index was categorized into lowest (poorest), second (poorer), middle, fourth (richer) and highest (richest) wealth quintile, the index was constructed using household asset data via a principal components analysis. All the six geopolitical zones were included in the study.

(ii) Antenatal and postnatal factors; We created a new variable combined birth interval and birth rank to compare the effect of birth order and subsequent birth interval with PLF, this variable was categorized into 5 categories namely; 1st birth rank, 2nd–3rd birth rank and preceding birth interval < =23 month, 2nd–3rd birth rank and preceding birth interval 24 month and above, 4th and above birth rank and preceding birth interval < =23 months, 4th and above and preceding birth interval 24 month and above. Number of antenatal care (ANC) visits was recoded into 0, 1–3, 4 and above visit. Place of delivery was categorized as home and health facility. Also considered was mode of delivery (spontaneous vaginal or caesarean-section). Birth type was recoded into singleton or twin/multiple, sex of child was as reported in the 2013 NDHS (male-female), size of child at birth based on mothers perception (subjective birth weight) and was categorized into three groups namely; large, average and small.

Statistical analysis

Chi square tests were performed to evaluate the association of the independent variables with PLF. Rate of PLF and distribution by different independent variables were reported as weighted percentages and 95 % CI using Stata version 13.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA). Before running the multivariate analysis, we examined the correlation between explanatory variables that had high potential for collinearity. Binary logistic regression was used to examine the likely predictors of PLF in Nigeria. Factors considered for the multivariable model were based from previous literature. The logistic regression analysis consisted of 2 models. Model 1 was the maternal socio-demographic model while model 2 included model 1+ antenatal and postnatal factors. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with their 95% confidence interval (CI) were reported. The multivariate analysis accounted for the sample design and sample weight using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) complex sample analysis method (SPSS version 21).

Results

Characteristics of the sample disaggregated by urban-rural residency

A higher proportion of urban and rural mothers at the time of birth were within the ages of 25–29 years (30.4% and 25.8%, respectively). 60.0% of urban mothers had secondary and above education, on the other hand, 57.8% of rural mothers had no education. The percentages of male and female children were more or less equal in both settings (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of mother-baby pair sample (Nigeria, DHS 2013)

| Urban | Rural | |||||||||||

| Characteristics | Total | Children who received PLF | Total | Children who received PLF | ||||||||

| N † | % ¶ | n § | % ‡ | 95%CI | P value | N † | % ¶ | n§ | % ‡ | 95%CI | P value | |

|

Maternal socio demographic, characteristics |

||||||||||||

| Mother's age at birth | ||||||||||||

| <=19 | 317 | 8.2 | 217 | 63.5 | (58.4–68.6) | <0.001 | 1336 | 16.9 | 1019 | 73.7 | (71.4–76.0) | <0.001 |

| 20–24 | 931 | 24.0 | 507 | 51.6 | (48.5–54.7) | 1998 | 25.3 | 1248 | 64.7 | (62.5–66.8) | ||

| 25–29 | 1181 | 30.4 | 630 | 48.4 | (45.7–51.1) | 2035 | 25.8 | 1256 | 64.2 | (62.1–66.4) | ||

| 30–34 | 820 | 21.1 | 387 | 44.2 | (41.0–47.5) | 1282 | 16.3 | 761 | 63.0 | (60.3–65.7) | ||

| >=35 | 630 | 16.2 | 334 | 49.9 | (46.1–53.7) | 1237 | 15.7 | 788 | 67.8 | (65.1–70.5) | ||

| Mother's education | ||||||||||||

| No education | 774 | 20.0 | 553 | 64.3 | (61.1–67.5) | <0.001 | 4557 | 57.8 | 3596 | 75.7 | (74.5–76.9) | <0.001 |

| Primary | 774 | 20.0 | 427 | 52.6 | (49.2–56.0) | 1502 | 19.0 | 731 | 55.8 | (53.1–58.4) | ||

| Secondary and above | 2331 | 60.0 | 1096 | 43.8 | (41.9–45.8) | 1829 | 23.2 | 745 | 47.3 | (44.8–49.8) | ||

| Mother's occupation | ||||||||||||

| Non-working | 1042 | 27.0 | 638 | 56.3 | (53.4–59.1) | <0.001 | 2645 | 33.7 | 1780 | 68.9 | (67.1–70.7) | 0.001 |

| Working | 2820 | 73.0 | 1427 | 47.3 | (45.5–49.0) | 5200 | 66.3 | 3272 | 65.1 | (63.8–66.4) | ||

| Wealth index | ||||||||||||

| Lowest | 144 | 3.7 | 93 | 64.6 | (56.9–72.6) | <0.001 | 2455 | 31.1 | 1995 | 77.0 | (75.3–78.6) | <0.001 |

| Second | 269 | 6.9 | 167 | 56.2 | (50.6–61.9) | 2463 | 31.2 | 1583 | 66.2 | (64.2–68.0) | ||

| Middle | 677 | 17.5 | 389 | 58.3 | (54.5–62.0) | 1675 | 21.2 | 911 | 58.3 | (55.9–60.8) | ||

| Fourth | 1216 | 31.3 | 686 | 52.3 | (49.6–55.0) | 975 | 12.4 | 467 | 57.7 | (54.3–61.1) | ||

| Highest | 1573 | 40.6 | 741 | 42.3 | (40.0–44.6) | 320 | 4.1 | 116 | 41.3 | (35.6–47.1) | ||

| Zones | ||||||||||||

| North Central | 530 | 13.7 | 146 | 37.6 | (32.8–42.4) | <0.001 | 1204 | 15.3 | 673 | 54.3 | (51.5–57.1) | <0.001 |

| North East | 505 | 13.0 | 321 | 63.6 | (59.4–67.8) | 1905 | 24.2 | 1217 | 79.6 | (77.6–81.6) | ||

| North West | 684 | 17.6 | 629 | 67.6 | (64.6–70.6) | 2963 | 37.6 | 2428 | 72.3 | (70.8–73.8) | ||

| South East | 688 | 17.7 | 405 | 55.0 | (51.4–58.6) | 382 | 4.8 | 193 | 56.8 | (51.5–62.0) | ||

| South South | 437 | 11.3 | 161 | 41.4 | (36.5–46.3) | 989 | 12.5 | 375 | 51.6 | (48.0–55.2) | ||

| South West | 1035 | 26.7 | 414 | 33.9 | (31.2–36.5) | 445 | 5.6 | 185 | 41.8 | (37.2–46.4) | ||

| Antenatal and postnatal factors | ||||||||||||

| Combined birth interval and rank | ||||||||||||

| 1st birth rank | 869 | 22.4 | 485 | 51.7 | (48.4–54.9) | <0.001 | 1447 | 18.4 | 947 | 66.5 | (64.1–67.0) | 0.052 |

| 2nd–3rd birth rank,<=23 months interval |

324 | 8.4 | 177 | 50.3 | (45.1–55.5) | 445 | 5.8 | 263 | 63.2 | (58.6–67.9) | ||

| 2nd–3rd birth rank, 24 months and above interval |

1079 | 27.9 | 498 | 43.8 | (40.9–46.7) | 1904 | 24.2 | 1222 | 64.7 | (62.5–66.8) | ||

| 4th and above birth rank,<=23 months interval |

253 | 6.5 | 149 | 56.9 | (50.7–62.7) | 618 | 7.9 | 380 | 64.5 | (60.7–68.4) | ||

| 4th and above birth rank, 24 months and above interval |

1346 | 34.8 | 757 | 51.4 | (48.9–60.0) | 3445 | 43.8 | 2246 | 68.0 | (66.4–69.6) | ||

| Antenatal care visit | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 384 | 10.3 | 268 | 63.1 | (58.4–67.6) | <0.001 | 3421 | 44.2 | 2539 | 73.2 | (71.8–74.7) | <0.001 |

| 1–3 | 432 | 11.6 | 276 | 57.4 | (52.9–61.7) | 1130 | 14.6 | 727 | 67.4 | (64.6–70.2) | ||

| 4 and above | 2917 | 78.1 | 1477 | 47.3 | (45.6–49.1) | 3187 | 41.2 | 1737 | 59.0 | (57.2–60.7) | ||

| Place of delivery | ||||||||||||

| Home | 1337 | 34.5 | 930 | 61.6 | (59.1–64.0) | <0.001 | 5937 | 75.4 | 4245 | 72.5 | (71.3–73.6) | <0.001 |

| Health facility | 2535 | 65.5 | 1145 | 43.1 | (41.2–45.0) | 1934 | 24.6 | 821 | 46.5 | (44.1–48.8) | ||

| Mode of delivery | ||||||||||||

| Spontaneous vaginal delivery | 3637 | 95.4 | 1964 | 50.0 | (48.5–51.6) | 0.238 | 7789 | 98.9 | 5025 | 66.6 | (65.5–67.7) | 0.009 |

| Caesarean section | 175 | 4.6 | 92 | 54.8 | (47.2–62.3) | 87 | 1.1 | 43 | 52.4 | (41.4–63.2) | ||

| Type of birth | ||||||||||||

| Single | 3814 | 98.3 | 2027 | 49.4 | (47.9–51.0) | <0.001 | 7759 | 98.4 | 4981 | 66.4 | (65.3–67.4) | 0.782 |

| Multiple | 65 | 1.7 | 49 | 73.1 | (61.8–83.4) | 129 | 1.6 | 91 | 67.9 | (59.8–75.7) | ||

| Sex of child | ||||||||||||

| Male | 1963 | 50.6 | 1027 | 49.4 | (47.2–51.5) | 0.642 | 4010 | 50.8 | 2566 | 66.9 | (65.4–68.4) | 0.370 |

| Female | 1916 | 49.4 | 1048 | 50.1 | (48.0–52.3) | 3878 | 49.2 | 2506 | 65.9 | (64.4–67.4) | ||

| Size of child at birth | ||||||||||||

| Small | 478 | 12.4 | 303 | 58.3 | (53.9–62.4) | <0.001 | 1321 | 16.8 | 964 | 75.1 | (72.7–77.4) | <0.001 |

| Average | 1604 | 41.5 | 939 | 53.3 | (51.0–55.7) | 3141 | 40.1 | 2133 | 70.7 | (69.0–72.3) | ||

| Large | 1784 | 46.1 | 828 | 44.1 | (41.8–46.3) | 3379 | 43.1 | 1952 | 59.2 | (57.5–60.9) | ||

Unweighted case numbers,

Column %,

Weighted case numbers,

Row %.

Prevalence of pre-lacteal feeds and types disaggregated by urban-rural residency

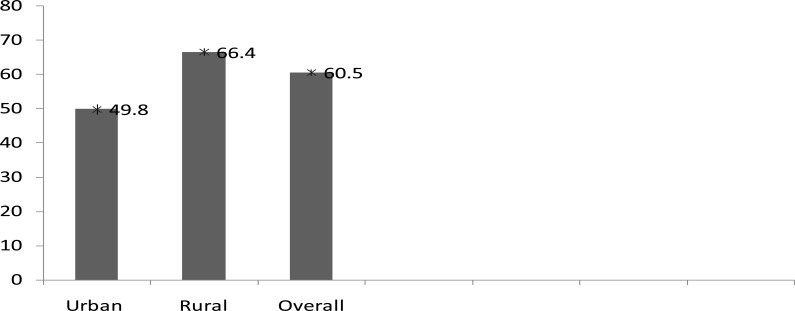

The overall prevalence of PLF in Nigeria was 60.5% (95 % CI: 59.6%–61.4%). The prevalence of PLF observed in urban area was 49.8%, (95 % CI: 48.2%–51.3%). while in rural areas it was 66.4% (95 % CI: 65.3%–67.5%) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Prevalence of pre-lacteal feeding in Nigeria (Nigeria, DHS 2013).

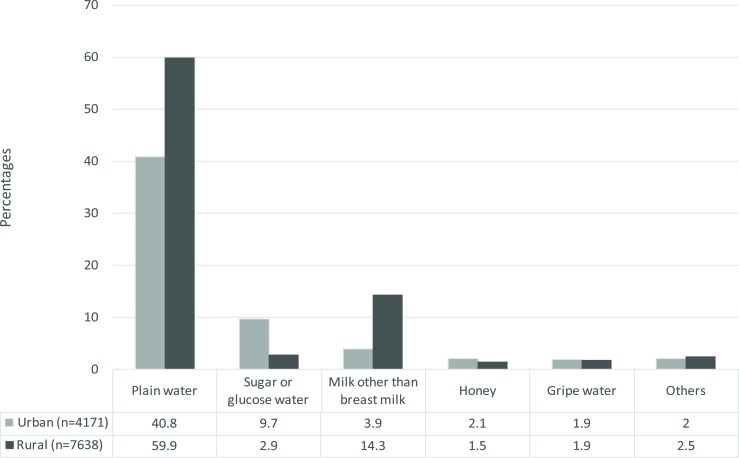

Sugar or glucose water (9.7 vs 2.9%) and honey (2.1 vs 1.5%) were predominatly given in urban Nigeria, whereas plain water (59.9 vs 40.8%), milk other than breast milk (14.3% vs 3.9%) and other pre-lacteal feeds (2.5 vs 2%) were commonly given in rural Nigeria. Gripe water was evenly given in both urban and rural Nigeria (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Determinants of PLF in urban-rural Nigeria (Nigeria, DHS 2013)

| Urban | Rural | ||||||||||||

| Model 1 † | Model 2 ¶ | Model 1 † | Model 2 ¶ | ||||||||||

| Characteristics | AOR | (95%CI) | p | AOR | 95%CI | p | AOR | (95%CI) | p | AOR | 95%CI | p | |

|

Maternal sociodemographic characteristics |

|||||||||||||

| Mother's age at birth | |||||||||||||

| <=19 | 1.61 | (1.13–2.28) | 0.008 | 1.42 | (0.95–2.12) | 0.092 | 1.42 | (1.16–1.73) | 0.001 | 1.35 | (1.02–1.79) | 0.037 | |

| 20–24 | 1.08 | (0.83–1.42) | 0.569 | 1.09 | (0.80–1.48) | 0.592 | 1.03 | (0.88–1.22) | 0.686 | 1.04 | (0.85–1.28) | 0.682 | |

| 25–29 | 1.07 | (0.82–1.39) | 0.638 | 1.03 | (0.77–1.37) | 0.857 | 0.95 | (0.81–1.12) | 0.553 | 0.98 | (0.82–1.17) | 0.800 | |

| 30–34 | 0.90 | (0.70–1.16) | 0.413 | 0.93 | (0.72–1.21) | 0.598 | 0.91 | (0.75–1.10) | 0.317 | 0.91 | (0.75–1.12) | 0.367 | |

| >=35 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Mother's education | |||||||||||||

| No education | 1.53 | (1.13–2.07) | 0.006 | 1.48 | (1.07–2.04) | 0.017 | 2.95 | (2.30–3.78) | <0.001 | 2.71 | (2.11–3.48) | <0.001 | |

| Primary | 1.33 | (1.04–1.69) | 0.022 | 1.31 | (1.02–1.69) | 0.037 | 1.40 | (1.15–1.71) | 0.001 | 1.34 | (1.08–1.66) | 0.008 | |

| Secondary and above | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Mother's occupation | |||||||||||||

| Non-working | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Working | 0.87 | (0.71–1.06) | 0.162 | 0.88 | (0.72–1.09) | 0.244 | 1.14 | (0.97–1.33) | 0.107 | 1.13 | (0.97–1.32) | 0.128 | |

| Wealth index | |||||||||||||

| Lowest | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Second | 0.79 | (0.47–1.32) | 0.364 | 0.78 | (0.45–1.35) | 0.369 | 0.80 | (0.66–0.98) | 0.028 | 0.84 | (0.69–1.03) | 0.099 | |

| Middle | 0.99 | (0.68–1.44) | 0.944 | 1.05 | (0.70–1.58) | 0.821 | 0.88 | (0.67–1.14) | 0.335 | 0.98 | (0.74–1.31) | 0.906 | |

| Fourth | 1.05 | (0.74–1.51) | 0.772 | 1.16 | (0.77–1.73) | 0.478 | 1.18 | (0.86–1.60) | 0.304 | 1.38 | (0.99–1.91) | 0.053 | |

| Highest | 1.03 | (0.70–1.53) | 0.869 | 1.11 | (0.72–1.72) | 0.646 | 0.73 | (0.50–1.07) | 0.103 | 0.93 | (0.62–1.38) | 0.714 | |

| Zones | |||||||||||||

| North Central | 1.06 | (0.73–1.54) | 0.778 | 1.04 | (0.70–1.54) | 0.845 | 1.49 | (0.96–2.33) | 0.076 | 1.45 | (0.95–2.21) | 0.089 | |

| North East | 2.69 | (1.88–3.86) | <0.001 | 2.63 | (1.78–3.89) | <0.001 | 3.76 | (2.33–6.05) | <0.001 | 3.25 | (2.05–5.16) | <0.001 | |

| North West | 3.37 | (2.31–4.90) | <0.001 | 3.20 | (2.13–4.81) | <0.001 | 2.22 | (1.42–3.47) | 0.001 | 1.83 | (1.19–2.82) | 0.006 | |

| South East | 2.41 | (1.74–3.32) | <0.001 | 2.19 | (1.56–3.08) | <0.001 | 2.67 | (1.53–4.65) | 0.001 | 2.72 | (1.55–4.75) | <0.001 | |

| South South | 1.38 | (0.99–1.91) | 0.056 | 1.31 | (0.89–1.93) | 0.177 | 1.88 | (1.21–2.91) | 0.005 | 1.66 | (1.08–2.55) | 0.021 | |

| South West | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

|

Antenatal and postnatal factors |

|||||||||||||

| Combined birth interval and rank |

|||||||||||||

| 1st birth rank | 1.25 | (0.94–1.67) | 0.129 | 1.11 | (0.86–1.45) | 0.426 | |||||||

| 2nd–3rd birth rank <=23 months interval |

1.03 | (0.76–1.39) | 0.871 | 1.00 | (0.74–1.34) | 0.983 | |||||||

| 2nd–3rd birth rank, 24 months and above interval |

0.94 | (0.73–1.21) | 0.627 | 0.99 | (0.83–1.19) | 0.948 | |||||||

| 4th birth rank <=23 months interval |

1.20 | (0.87–1.67) | 0.264 | 0.82 | (0.65–1.04) | 0.095 | |||||||

| 4th birth rank, 24 months and above interval |

1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Antenatal care visit | |||||||||||||

| None | 0.84 | (0.61–1.16) | 0.290 | 0.91 | (0.76–1.08) | 0.280 | |||||||

| 1–3 | 0.84 | (0.62–1.15) | 0.285 | 0.96 | (0.78–1.19) | 0.722 | |||||||

| 4 and above | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Place of delivery | |||||||||||||

| Home | 1.53 | (1.24–1.89) | <0.001 | 2.05 | (1.72–2.43) | <0.001 | |||||||

| Health facility | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Mode of delivery | |||||||||||||

| Spontaneous vaginal delivery |

1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Caesarean section | 1.87 | (1.25–2.80) | 0.003 | 1.21 | (0.68–2.15) | 0.511 | |||||||

| Type of birth | |||||||||||||

| Single | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Multiple | 2.37 | (1.14–4.95) | 0.022 | 1.20 | (0.75–1.94) | 0.449 | |||||||

| Size of child at birth | |||||||||||||

| Small | 1.46 | (1.10–1.94) | 0.009 | 1.77 | (1.44–2.17) | <0.001 | |||||||

| Average | 1.57 | (1.27–1.93) | <0.001 | 1.66 | (1.45–1.91) | <0.001 | |||||||

| Large | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Sex of child | |||||||||||||

| Male | 1.02 | (0.85–1.21) | 0.863 | 1.07 | (0.96–1.21) | 0.227 | |||||||

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

|

Nagelkarke Pseudo R Square |

0.114 | 0.141 | 0.127 | 0.160 | |||||||||

Model 1 = Maternal sociodemographic characteristics,

Model 2= Model1 + Antenatal and postnatal factors.

FIG. 2.

Types of prelacteal feed given among last-born children under two years of age (Nigeria, DHS 2013)

Note: Others category include any of the following prelacteal feeds; sugar/salt solution, fruit juice, infant formula, tea/infusions, coffee, or other.

Bivariate results

Urban Nigeria: In urban Nigeria, the explanatory variables that were significantly associated with higher PLF rates included: Mothers age at birth being <=19 years, no education, non-working mothers, belonging to the lowest wealth quartile, all geopolitical zones as compared to the South Western zone, 4th birth rank and above with preceding birth interval of less than or equal to 23 months, no ANC visits, home delivery, multiple births, and small size of baby at birth (Table 1).

Rural Nigeria: In rural Nigeria, the significant covariates associated with higher PLF rates included; Mother's age at birth being <=19 years, no education, non-working mothers, belonging to the lowest wealth quintile, all geopolitical zones as compared to the South West zone, no ANC visits, home delivery, spontaneous vaginal delivery and small size of child at birth. (Table 2).

Multivariate results

Urban Nigeria: When maternal socio-demographic, antenatal and postnatal factors were controlled for (Model 2), urban mothers with no education and primary educational status had significantly 48 and 31% higher odds of PLF as compared to mothers with secondary and above educational status (Adjusted Odd Ratio (AOR)=1.48, 95% CI=1.07–2.04 and AOR=1.31, 95% CI=1.02–1.69, respectively). Also, compared to the South Western geopolitical zone, urban mothers, who lived in the following geopolitical zones of Nigeria, were significantly more likely to give prelacteal feeds: North East (AOR=2.65, 95% CI=1.78–3.89); North West (AOR=3.20, 95% CI=2.13–4.81); and South East (AOR=2.19, 95% CI=1.56–3.08). Urban mothers who delivered at home had significantly higher odds of PLF as compared to urban mothers whose place of delivery were health facility (AOR=1.53, 95% CI=1.24–1.89). The odds of PLF was 1.87 times higher for urban mothers who had caesarean section as compared to urban mothers who had spontaneous vaginal delivery (AOR=1.87, 95% CI=1.25–2.80). In addition, urban mothers with multiple births had a 2.37 times the odds of PLF as compared to mothers with singleton birth (AOR= 2.37, 95% CI=1.14–4.95). We further observed that urban mothers who perceived the size of their child at birth to be small or average had significantly higher odds for PLF as compared to urban mothers who perceived the size of their child at birth to be large (AOR=1.46, 95% CI=1.10–1.94 and AOR=1.57, 95% CI=1.27–1.93, respectively).

Rural Nigeria: In rural Nigeria, Model 2 showed that mothers who were aged <=19 years at birth were significantly more likely to give pre-lacteal feeds as compared to those aged 35 years and above at birth (AOR=1.35, 95% CI=1.02–1.79). Also, rural mothers with no education (AOR=2.71, 95% CI=2.11–3.48) and primary educational status (AOR=1.34, 95 % CI=1.08–1.66) were significantly more likely to give pre-lacteal feeds as compared to mothers with secondary and above educational status. Compared to the South Western geopolitical zone, rural mothers, who lived in the following geopolitical zones of Nigeria, were significantly more likely to give prelacteal feeds: North East (AOR=3.25, 95% CI=2.05–5.16); North West (AOR=1.83, 95% CI= 1.19–2.82); South East (AOR=2.72, 95% CI=1.55–4.75) and South South (AOR=1.66, 95% CI=1.08–2.54). The odds of PLF was 2.05 times higher for rural mothers who delivered at home as compared to mothers who delivered in a health facility (AOR=2.05, 95% CI= 1.72–2.43). Rural mothers who perceived their babies as small (AOR=1.77, 95 CI=1.44–2.17) or average sized (AOR 1.66, 95% CI=1.45–1.91) at birth were more likely to give pre-lacteal feeds as compared to rural mothers who perceived their child to be large at birth.

Discussion

The main finding of this study was that PLF practice was more common in rural Nigeria (66.4%) as compared to urban Nigeria (49.8%). Prevalence of PLF was also higher in rural as compared to urban areas in India and Malawi14–15. The observed difference in PLF prevalence between urban and rural areas may be explained by the fact that urban areas differ socio-culturally from rural areas in many ways and such differences at both individual, household and community levels may play a role16.

The commonest prelacteal feeds in Nigeria were plain water, sugar or glucose water and milk other than breast milk. This agrees with previous studies done in countries like Kenya17, Philippines18, and Nepal7. We also observed that sugar or glucose-water and honey were given more in urban Nigeria, whereas, plain water, milk other than breast milk and other pre-lacteal feeds were given commonly more in rural Nigeria. We postulated that the variation between urban and rural areas in the types of pre-lacteal feeds could be attributed to the availability of different feeds and/or cultural differences in both settings.

In the full model, urban and rural Nigeria shared similarities with respect to factors like mothers education, place of delivery, and size of child at birth being significant predictors of PLF, however some factors such as mode of delivery, type of birth, and mother's age at birth, showed variation in terms of significance according to place of residence. Mode of delivery, and type of birth were significant predictors of PLF only in urban Nigeria, whereas, mother's age at birth was a significant predictors of PLF only in rural Nigeria. Zones also showed variations in the odds of PLF according to place of residence. In urban Nigeria, caesarean section contributed significantly to a higher likelihood of PLF. The high rates of PLF among women who had caesarean section as compared to spontaneous vaginal deliveries could be linked to the fact that caesarean section (CS) is associated with prolonged maternal-infant separation, antibiotics safety concern on the child, pain and discomfort, and longer stay in the hospital19. However, we observed a lack of significance between caesarean section and PLF in rural Nigeria, though, rural mothers who had CS were more likely to give pre-lacteal feeds as compared to rural mothers who had spontaneous vaginal delivery. The 2013 NDHS reported the prevalence of caesarean section to be 1.0 % in rural areas as compared to 3.9 % in urban areas10.

The result of this study showed that urban mothers who had multiple births were more likely to give PLF as compared to urban mothers who had singleton births. This result is in consonance with findings of a previous study that report that establishment of breastfeeding after multiple births is extremely difficult20. Another study reported the following reasons for breast feeding among mothers with multiple births; mother simply did not want to breast feed, maternal or infant illness, physician advice against insufficient milk supply, and not enough time21. In the case of rural Nigeria, rural mothers with multiple where also more likely to give pre-lacteal feed as compared to rural mothers with singleton birth, however, this finding was not a significant finding for rural Nigeria. We postulated that the major reason for the lack of significance among rural mothers was that rural mothers who had multiple births have lower access to expensive infant feeding alternatives as compared to urban mothers. On the other hand, this argument alone cannot explain the lack of significance observed in rural Nigeria and raises the need for further investigation.

In rural Nigeria, mothers aged less than or equal to 19 years were significantly more likely to offer pre-lacteal feed as compared to older mothers aged 35 years and above. The reason could be that younger mothers may lack knowledge or experience about appropriate breastfeeding practices22. In urban Nigeria, this finding was true controlling only for other maternal socio-demographic characteristics. However, this significance was lost when antenatal and postnatal variables were controlled for.

Maternal education was an important determinant of PLF, although not strongly so, in both settings. The odds of PLF were higher for mothers with no education or primary education as compared to mothers with secondary and above educational status. A probable reason could be that the longer time spent in formal education put mothers in a better position to self-educate themselves on infant nutrition23.

Our study findings showed that place of delivery was significantly associated with PLF practice in both urban and rural Nigeria. Mothers who delivered at home were more likely to give pre-lacteal feeds as compared to mothers who delivered in a health facility. This is in consonance with a study done in Ethopia24. These findings could be as a result of the fact that mothers who deliver in the hands of health personnel's were more likely to be encouraged and counseled for healthy infant feeding practices. In the Nigerian context, our result was not a surprising finding as many of the primary health care centers and hospitals in Nigeria have adopted the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) and the policy in these health care facilities is for the midwife or any other available skilled provider to give newborn infants no food or drink other than breast milk, unless medically indicated25.

Mothers in both urban and rural Nigeria, mothers who perceived their infant to be small or average sized at birth were more likely to introduce pre-lacteal feeds as compared to mothers who perceived their infants to be large sized. In consonance, Flaherman and colleagues found that higher birth weight was strongly associated with exclusive breastfeeding26 while Berde and Yalcin12 reported that larged sized infant had higher likelihood of EIBF. Flaherman and collegues suggested that mothers of smaller sized infants might worry more about infant weight and about milk supply, possibly leading to unnecessary formula supplementation26.

The current study observed significant zonal variations in PLF odds in both urban and rural Nigeria. Regional differences in PLF in both urban and rural Nigeria could be in part a function of access to health service, inequitable distribution of health services, health information, resources and other geographic differences, as shown in another study7. In addition, cultural practices may play a role and this role has been observed to vary across different settings7,27–31.

This study is not without some limitations, the study limitation relates to the fact that the data was based on a cross-sectional study and is subject to recall bias. In addition, due to the cross-sectional nature of the data, caution must be exercised in making causal influence of the identified determinants of PLF. On the other hand, the study has strength of being a nationally representive study with a high response rate, in addition, complex sample analysis was performed to account for the sampling strategy and sample weight, thus, the findings are generalizable to the entire country. Future studies using qualitative approaches such as in-depth interview of some key informants will help in enriching the knowledge on PLF in Nigeria.

Conclusion

We observed differences in PLF between urban and rural areas, with factors affecting PLF showing variation in terms of significance according to place of residence. Interventions aimed at decreasing PLF rate should be through a tailored approach, targeting at risk sub groups discovered in our study.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Measure DHS for making available the 2013 NDHS data set for this study

Disclosure

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Sources of support

Nil

References

- 1.Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJD, Franca GVA, Horton S, Krasevec J, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475–490. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Godhia ML, Patel N. Colostrum - its Composition, Benefits as a Nutraceutical - A Review. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci. 2013;1(1):37–47. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization/United Nations Children's Fund, author. The baby friendly initiative. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mukuria AG, Kothari MT, Abderahim N. Infant and Young Child Feeding Updates, Calverton. Maryland, USA: ORC Macro; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Legesse M, Demena M, Mesfin F, Haile D. Prelacteal feeding practices and associated factors among mothers of children aged less than 24 months in Raya Kobo district, North Eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Int Breastfeed J. 2014;9(1):189. doi: 10.1186/s13006-014-0025-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perez-Escamilla R, Segura-Millan S, Canahuati J. Pre-lacteal feeding is negatively associated with breastfeeding outcomes in Honduras. J Nutr. 1996;126(11):2765–2773. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.11.2765. (1996) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khanal V, Adhikari M, Sauer K, Zhao Y. Factors associated with the introduction of prelacteal feeds in Nepal: findings from the Nepal demographic and health survey 2011. Int Breastfeed J. 2013;8(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore ER, Anderson GC, Bergman N, Dowswell T. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;(5):CD003519. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003519.pub3. Art. No. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goyle A, Jain P, Vyas S, Saraf H, Sekhawat N. Colostrum and prelacteal feeding practices followed by families of pavement and roadside squatter settlements. Indian J Prev Soc Med. 2004;25(1):58–62. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Population Commission (NPC) (Nigeria) and ICF International, author. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2013. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF International; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.The World Bank Group, author. World Bank Open Data. Washington D.C., USA: 2016. [March 2017]. Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berde AS, Yalcin SS. Determinants of early initiation of breastfeeding in Nigeria: a population-based study using the 2013 demograhic and health survey data. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2016;16(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0818-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ibadin OM, Ofili NA, Monday P, Nwajei CJ. Prelacteal feeding practices among lactating mothers in Benin City, Nigeria. Niger J Paed. 2013;40(2):139–144. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raina SK, Vijay M, Gurdeep S. Determinants of Prelacteal Feeding among infants of RS Pura block of Jammu and Kashmir, India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2012;1(1):27–29. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.94446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Statistical Office (NSO) and ICF Macro, author. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2010. Zomba, Malawi, and Calverton, Maryland, USA: NSO and ICF Macro; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tran TK, Nguyen CT, Nguyen HD, Eriksson B, Bondjers G, Gottval K, et al. Urban-rural disparities in antenatal care utilization: a study of two cohorts of pregnant women in Vietnam. BMC health services research. 2011;11(1):120. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lakati AS, Makokha OA, Binns CW, Kombe Y. The effect of pre-lacteal feeding on full breastfeeding in Nairobi, Kenya. East African Journal of Public Health. 2010;7(3):258–262. doi: 10.4314/eajph.v7i3.64737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Statistics Office (NSO) and ICF Macro, author. Philippines National Demographic and Health Survey 2008. Manila, Philippines, and Calverton, Md, USA: NSO and ICF Macro; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prez-Escamilla R, Maulen Radovan I, Dewey KG. The association between caesarean delivery and breastfeeding outcomes in Mexican women. Am j Public health. 1996;86(6):832–836. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.6.832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yokoyama Y, Ooki S. Breast-feeding and bottle-feeding of twins, triplets and higher order multiple births. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. 2004;51(11):969–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Addy HA. The breast-feeding of twins. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. 1975;21(5):231–239. doi: 10.1093/tropej/21.5.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Victor R, Baines SK, Agho KE, Dibley MJ. Determinants of breastfeeding indicators among children less than 24 months of age in Tanzania: a secondary analysis of the 2010 Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey. BMJ open. 2013;3(1):e001529. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skafida V. The relative importance of social class and maternal education for breast-feeding initiation. Public health nutrition. 2009;12(12):2285–2292. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009004947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bekele Y, Mengistie B, Mesfine F. Prelacteal feeding practice and associated factors among mothers attending immunization clinic in Harari Region public health facilities, Eastern Ethiopia. Open J Prev Med. 2014;4(7):529–534. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okafor IP, Olatona FA, Olufemi OA. Breastfeeding practices of mothers of young children in Lagos, Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Paediatrics. 2013;41(1):43–47. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flaherman VJ, McKean M, Cabana MD. Higher birth weight improves rates of exclusive breastfeeding through 3 months. ICAN: Infant, Child, & Adolescent Nutrition. 2013;5(4):200–203. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khadduri R, Marsh DR, Rasmussen B, Bari A, Nazir R, Darmstadt Household knowledge and practices of newborn and maternal health in Haripur district, Pakistan. Journal of Perinatology. 2008;28(3):182–187. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steinman L, Doescher M, Keppel GA, Pak Gorstein S, Graham E, Haq A, et al. Understanding infant feeding beliefs, practices and preferred nutrition education and health provider approaches: an exploratory study with Somali mothers in the USA. Matern Child Nutr. 2009;6(1):67–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2009.00185.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ergenekon-Ozelci P, Elmaci N, Ertem M, Saka G. Breastfeeding beliefs and practices among migrant mothers in slums of Diyarbakir, Turkey, 2001. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16(2):143–148. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Semega-Janneh IJ, Bohler E, Holm H, Matheson I, Holmboe Ottesen G. Promoting breastfeeding in rural Gambia: combining traditional and modern knowledge. Health Policy Plan. 2001;16(2):199–205. doi: 10.1093/heapol/16.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roy MP, Mohan U, Singh SK, Vijay KS, Anand SK. Determinants of Pre-Lacteal Feeding in Rural Northern India. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5(5):658–663. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]