Abstract

Background

The goal of this study was to compare angiographic interpretation of coronary arteriograms by sites in community practice versus those made by a centralized angiographic core laboratory.

Methods and Results

The study population consisted of 2013 American College of Cardiology–National Cardiovascular Data Registry (ACC–NCDR) records with 2- and 3- vessel coronary disease from 54 sites in 2004 to 2007. The primary analysis compared Registry (NCDR)-defined 2- and 3-vessel disease versus those from an angiographic core laboratory analysis. Vessel-level kappa coefficients suggested moderate agreement between NCDR and core laboratory analysis, ranging from kappa=0.39 (95% confidence intervals, 0.32–0.45) for the left anterior descending artery to kappa=0.59 (95% confidence intervals, 0.55–0.64) for the right coronary artery. Overall, 6.3% (n=127 out of 2013) of those patients identified with multivessel disease at NCDR sites had had 0- or 1-vessel disease by core laboratory reading. There was no directional bias with regard to overcall, that is, 12.3% of cases read as 3-vessel disease by the sites were read as <3-vessel disease by the core laboratory, and 13.9% of core laboratory 3-vessel cases were read as <3-vessel by the sites. For a subset of patients with left main coronary disease, registry overcall was not linked to increased rates of mortality or myocardial infarction.

Conclusions

There was only modest agreement between angiographic readings in clinical practice and those from an independent core laboratory. Further study will be needed because the implications for patient management are uncertain.

Keywords: angiography, catheterization, percutaneous coronary intervention, program evaluation

With ≈600 000 percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs) being performed in the United States each year, procedure appropriateness and the clinical validation of angiographic scores of coronary artery disease extent and complexity have emerged as paramount issues in current cardiovascular medicine.1,2 Previous analyses of the appropriateness of coronary interventions have assumed that the assessment of the clinical site of the disease extent and left main severity are accurate, and the angiograms have generally not been independently verified by a core laboratory.1,3–6 Clinical interpretation of angiograms can be quite variable, even when a rigorous scoring system such as the Synergy between PCI with Taxus and Cardiac Surgery (SYNTAX) score is applied.7–9 There has been no description, in this or other similar trials, of whether interobserver disagreement was tied to poor clinical outcomes.

The American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF), the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS), and the Duke Clinical Research Institute are collaborating on a comparative effectiveness study (American College of Cardiology Foundation–Society of Thoracic Surgeons Collaboration on the Comparative Effectiveness of Revascularization Strategies [ASCERT]) of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and PCI, funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health.10,11 An additional aim of ASCERT is to develop novel, long-term mortality risk prediction models for CABG and PCI.12,13 The assessment of the clinical sites of the disease extent is included in these models, and the quality of the clinical interpretation of the sites of the angiogram is therefore integral to the validity of this model. In addition, the number of vessels diseased by angiographic assessment was used in the propensity score model for comparative effectiveness in ASCERT.10 However, far more importantly, angiographic assessment is used in clinical decision making on a routine basis.

The goals of the present study were (1) to assess the rate of concordance between clinical sites and an independent angiographic core laboratory in their interpretation of the angiogram, and (2) to determine whether discordance among interpreters served as a marker for poor clinical outcomes.

Methods

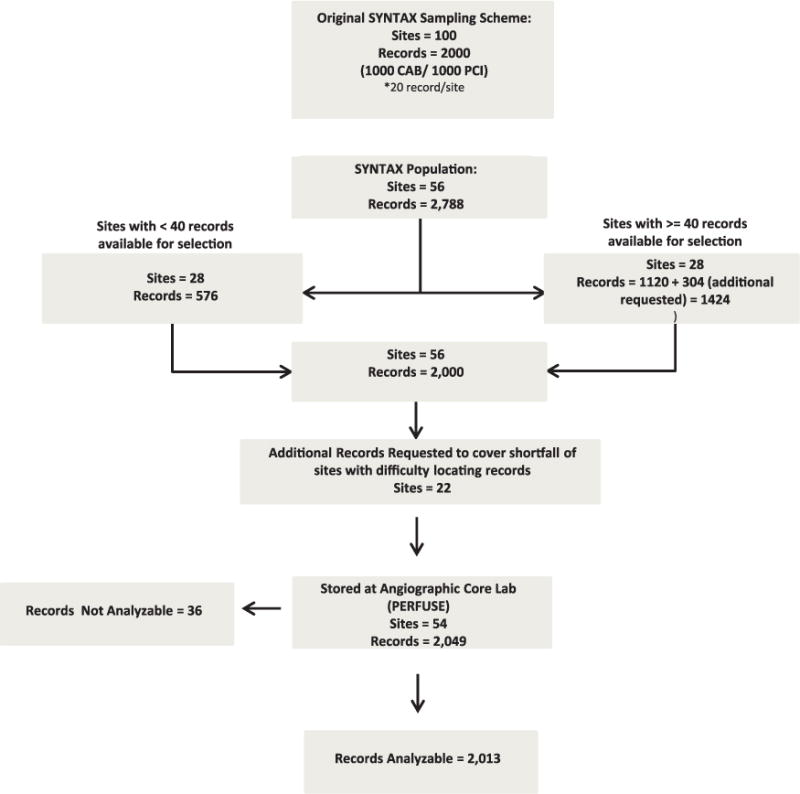

The sampling scheme for the SYNTAX substudy is described in Figure 1. Briefly, patients with diagnostic catheterization information in the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) undergoing PCI or CABG and with 2- and 3- vessel coronary artery disease were randomly selected from the NCDR and STS registry, respectively, in equal proportions and were submitted to the angiographic core laboratory for validation of the recorded number of diseased vessels (N=2049) by visual assessment. The study was approved by an institutional review committee, and the subjects involved in the registry gave informed consent. A total of 36 records that had >1 cardiac catheterization laboratory visit on the same procedure date were excluded. The final study population included 2013 patient records (932 ultimately undergoing PCI, 1081 ultimately undergoing CABG) from 54 hospitals.

Figure 1.

Study population. Records available from Synergy between percutaneous coronary intervention with Taxus and Cardiac Surgery (SYNTAX) study with angiographic analysis performed at the Percutaneous/Pharmacologic Endoluminal Revascularization for Unstable Syndrome and its Evaluation (PERFUSE) angiographic core laboratory.

The primary end point was a lesion-based analysis evaluating the rate of concordance (ie, the kappa coefficient) between the site and the core laboratory as to whether a significant (>50%) lesion was present by visual assessment anywhere in the vessel. Clinical outcomes including death and recurrent myocardial infarction were evaluated for patients with overcalled left main disease (ie, patients with left main disease by registry analysis but not by core laboratory analysis) compared with those with left main agreement.

Patient characteristics are presented for the overall study population and also stratified by agreement of NCDR and Percutaneous/Pharmacologic Endoluminal Revascularization for Unstable Syndrome and its Evaluation (PERFUSE) data in all 4 coronary vessels (left main, left anterior descending, left circumflex, and right coronary artery) versus disagreement in ≥1 vessel. Summary statistics are presented as percentages for categorical variables and medians with 25th and 75th percentiles for continuous variables. Baseline patient characteristics were compared across treatment groups using the Pearson χ2 test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variable distributions; 2×2 tables were constructed describing disease status for each coronary vessel based on NCDR and core laboratory data; from these tables kappa coefficients for agreement were derived. Clinical outcomes are presented as survival curves, which were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method for censored data. Follow-up time was administratively censored on December 31, 2008. The log-rank test was used to evaluate significant differences between the survival curves in the left main concordant and discordant groups (R statistical software, version 2.13.0, Survival Library).

Core laboratory angiographers were blinded to site interpretations and clinical information for each case. The angiograms were performed per clinical protocol of each site, and the number of views for each study was not mandated. The angiograms were of high quality and had orthogonal views sufficient to evaluate the appropriate revascularization strategy. All core laboratory angiograms were overread by the chair of the PERFUSE angiographic core laboratory. All PERFUSE angiographers, cardiologists, and technicians passed an angiographic certification test after rigorous training, including completion and review of ≥50 angiographic films with a certified interventional cardiologist.

Results

Table 1 depicts the characteristics of the overall study population (n=2013), as well as clinical predictors stratified by agreement of NCDR and the core laboratory data in all 4 coronary vessels (n=1225) versus disagreement in ≥vessel (n=788). Overall, there were no significant differences between groups. The only characteristic that reached a statistically significant difference between groups was history of chronic lung disease (16.7% versus 22.0%, P=0.003).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristics | Overall (N=2013) |

Agreement All Vessels (N=1225) |

Disagreement 1* Vessels (N=788) |

P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, no. (%) | ||||

| ≥85 | 109 (5.4) | 73 (6.0) | 36 (4.6) | 0.35 |

| ≥80 and <85 | 295 (14.7) | 179 (14.6) | 116 (14.7) | |

| ≥75 and <80 | 476 (23.7) | 278 (22.7) | 198 (25.1) | |

| ≥70 and <75 | 559 (27.8) | 324 (26.5) | 235 (29.8) | |

| ≥65 and <70 | 574 (28.5) | 371 (30.3) | 203 (25.8) | |

| Sex, no. (%) | ||||

| Female | 738 (36.7) | 439 (35.8) | 299 (37.9) | 0.34 |

| Male | 1275 (63.3) | 786 (64.2) | 489 (62.1) | |

| Race/ethnicity, no. (%) | ||||

| Other | 75 (3.7) | 48 (3.9) | 27 (3.4) | 0.17 |

| Native American | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.3) | |

| Asian | 16 (0.8) | 8 (0.7) | 8 (1.0) | |

| Hispanic | 17 (0.8) | 14 (1.1) | 3 (0.4) | |

| Black | 66 (3.3) | 38 (3.1) | 28 (3.6) | |

| White | 1833 (91.1) | 1116 (91.1) | 717 (91.0) | |

| Risk factors | ||||

| BMI category, kg/m2,‡ no. (%) | ||||

| ≥35 | 240 (11.9) | 148 (12.1) | 92 (11.7) | 0.93 |

| ≥30 and <35 | 452 (22.5) | 279 (22.8) | 173 (22.0) | |

| ≥25 and >30 | 829 (41.2) | 493 (40.2) | 336 (42.6) | |

| ≥18.5 and <25 | 471 (232.4) | 290 (23.7) | 181 (23.0) | |

| <18.5 | 19 (0.9) | 13 (1.1) | 6 (0.8) | |

| Previous MI (>7 d), no. (%) | ||||

| Yes | 320 (15.9) | 197 (16.1) | 123 (15.6) | 0.76 |

| No | 1685 (83.7) | 1022 (83.4) | 663 (84.1) | |

| Previous CHF, no. (%) | ||||

| Yes | 208 (10.3) | 128 (10.5) | 80 (10.2) | 0.83 |

| No | 1799 (89.4) | 1093 (89.2) | 706 (89.6) | |

| Diabetes/control, no. (%) | ||||

| Insulin diabetes mellitus | 191 (9.5) | 119 (9.7) | 72 (9.1) | 0.18 |

| Noninsulin diabetes mellitus | 532 (26.5) | 340 (27.8) | 192 (24.4) | |

| No diabetes mellitus | 1287 (63.9) | 764 (62.4) | 523 (66.4) | |

| Renal failure/dialysis, no. (%) | ||||

| Dialysis | 20 (1.0) | 15 (1.2) | 5 (0.6) | 0.29 |

| Nondialysis renal failure | 82 (4.1) | 46 (3.8) | 36 (4.6) | |

| No renal failure | 1911 (94.9) | 1164 (95.0) | 747 (94.8) | |

| Cerebrovascular disease, no. (%) | ||||

| Yes | 319 (15.9) | 189 (15.4) | 130 (16.5) | 0.53 |

| No | 1690 (84.0) | 1033 (84.3) | 657 (83.4) | |

| Peripheral vascular disease, no. (%) | ||||

| Yes | 309 (15.3) | 182 (14.9) | 127 (16.1) | 0.45 |

| No | 1700 (84.5) | 1040 (84.9) | 660 (83.8) | |

| Chronic lung disease, no. (%) | ||||

| Yes | 379 (18.8) | 205 (16.7) | 174 (22.1) | 0.003 |

| No | 1628 (80.9) | 1015 (82.9) | 613 (77.8) | |

| Hypertension, no. (%) | ||||

| Yes | 1644 (81.7) | 1002 (81.8) | 642 (81.5) | 0.84 |

| No | 366 (18.2) | 221 (18.0) | 145 (18.4) | |

| Smoking status, no. (%) | ||||

| Current | 242 (12.0) | 142 (11.6) | 100 (12.7) | 0.41 |

| Former | 819 (40.7) | 512 (41.8) | 307 (39.0) | |

| No | 943 (46.9) | 565 (46.1) | 378 (48.0) | |

| Dyslipidemia, no. (%) | ||||

| Yes | 1473 (73.2) | 890 (72.7) | 583 (74.0) | 0.56 |

| No | 535 (26.6) | 331 (27.0) | 204 (25.9) | |

| Family history of CAD, no. (%) | ||||

| Yes | 530 (26.3) | 323 (26.4) | 207 (26.3) | 0.96 |

| No | 1480 (73.5) | 900 (73.5) | 580 (73.6) | |

| Ejection fraction, no. (%) | ||||

| ≥60 | 950 (47.2) | 581 (47.4) | 369 (46.8) | 0.8254 |

| ≥45 and <60 | 679 (33.7) | 400 (32.7) | 279 (35.4) | |

| ≥30 and <45 | 293 (14.6) | 189 (15.4) | 104 (13.2) | |

| <30 | 91 (4.5) | 55 (4.5) | 36 (4.6) | |

| Treatment | ||||

| CABG, no. (%) | 1081 (53.7) | 607 (49.6) | 474 (60.2) | <0.0001 |

| PCI, no. (%) | 932 (46.3) | 618 (50.5) | 314 (39.9) | |

| Other | ||||

| Symptoms on admission | ||||

| ACS: STEMI | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.4) | 0.24 |

| ACS: Non-STEMI | 36 (1.8) | 24 (2.0) | 12 (1.5) | |

| ACS: Unstable angina | 947 (47.0) | 593 (48.4) | 354 (44.9) | |

| Stable angina | 450 (22.4) | 258 (21.1) | 192 (24.4) | |

| Atypical chest pain | 241 (12.0) | 142 (11.6) | 99 (12.6) | |

| No symptoms/angina | 335 (16.6) | 207 (16.9) | 128 (16.2) | |

| Cardiogenic shock | ||||

| Yes | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.3) | 0.33 |

| No | 2004 (99.6) | 1220 (99.6) | 784 (99.5) | |

| IABP | ||||

| Yes | 38 (1.9) | 16 (1.3) | 22 (2.8) | 0.017 |

| No | 1973 (98.0 | 1208 (98.6) | 765 (97.0) | |

| Cath status | ||||

| Emergency | 23 (1.1) | 14 (1.1) | 9 (1.1) | 0.40 |

| Urgent | 698 (34.7) | 437 (35.7) | 261 (33.1) | |

| Elective | 1221 (60.7) | 726 (59.2) | 495 (62.8) | |

| Missing | 71 (3.5) | 48 (3.9) | 23 (2.9) |

Data are presented for the overall patient population, as well as for the 2 subgroups: those patients with angiographic agreement between the registry analysis (American College of Cardiology–National Cardiovascular Data Registry) and the core laboratory analysis (Percutaneous/Pharmacologic Endoluminal Revascularization for Unstable Syndrome and its Evaluation [PERFUSE]), as well as those patients with disagreement in ≥1 vessels. Hypothesis testing was performed to compare these 2 groups, and P values are presented. Missing data are not shown because they do not exceed 0.4% in any category, except for other: cath status, for which missing data are shown. All tests treat the column variable as ordinal. ACS indicates acute coronary syndrome; BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; and STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

P values do not correspond to the table exactly as it is presented here. More appropriately, P values were calculated by comparing only nonmissing row values.

P values are based on χ2 rank–based group means score statistics for all categorical row variables (equivalent to Kruskal–Wallis test for row variables with 3+ levels and Wilcoxon test for 2 levels).

P values are based on χ2 1 degree of freedom rank correlation statistics for all continuous/ordinal row variables.

There was no direction bias with regard to overcall, that is, 20.9% (247 out of 1182) of cases read as 3-vessel disease by the sites were read as <3-vessel disease by the core laboratory, and 23.0% (280 out of 1215) of core laboratory 3-vessel cases were read as <3-vessel by the sites. Table 2 depicts agreement between NCDR and core laboratory data at the vessel level. All kappa coefficients presented fall in the range of at most moderate agreement, with the highest kappa values occurring in right coronary artery group (kappa=0.59, 95% CI [0.55–0.64]). Vessel-level data focusing on left main disease demonstrated that 11.2% (17 out of 152) of the cases called as left main disease by the core laboratory were deemed normal by registry data (core laboratory overcall), whereas 56.7% (177 out of 312) that were read as left main disease by the registry but had no left main lesion by core laboratory analysis (registry overcall).

Table 2.

Analysis of Agreement on Vessel-Level Results

| Core Laboratory Readings

|

||

|---|---|---|

| NCDR Readings | No Disease | Disease |

| Left main (Kappa=0.53, 95% CI [0.48–0.59]) | ||

| No disease* | 1684 (83.66%) | 17 (0.84%) |

| Disease | 177 (8.79%) | 135 (6.71%) |

| LAD (Kappa=0.39, 95% CI [0.32–0.45]) | ||

| No disease | 92 (4.57%) | 104 (5.17%) |

| Disease | 120 (5.96%) | 1697 (84.30%) |

| Circumflex (Kappa=0.53, 95% CI [0.53–0.57]) | ||

| No disease | 275 (13.66%) | 181 (8.99%) |

| Disease | 143 (7.10%) | 1414 (70.24%) |

| RCA (Kappa=0.59, 95% CI [0.55–0.64]) | ||

| No disease | 221 (10.98%) | 98 (4.87%) |

| Disease | 128 (6.36%) | 1566 (77.79%) |

| 3+ Vessel disease (Kappa=0.46, 95% CI [0.42–0.50]) | ||

| < 3VD | ≥3VD | |

| < 3VD | 551 (27.37%) | 280 (13.91%) |

| ≥3VD | 247 (12.27%) | 935 (46.45%) |

Kappa coefficients are presented demonstrating whether there is agreement regarding the presence/absence of stenosis as determined by Percutaneous/Pharmacologic Endoluminal Revascularization for Unstable Syndrome and its Evaluation (PERFUSE) versus CATHPCI. CI indicates confidence intervals; LAD, left anterior descending; NCDR, National Cardiovascular Data Registry; RCA, right coronary artery; and VD, vessel disease.

Disease is defined as vessel stenosis ≥50%.

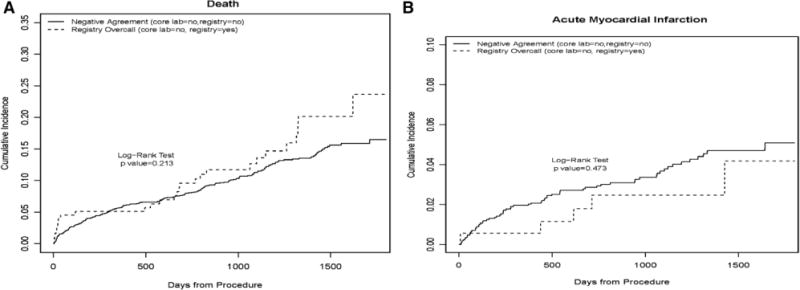

Survival analysis was performed evaluating the clinical outcomes of death and recurrent myocardial infarction because they relate to both negatively concordant left main disease (patients deemed to have no left main coronary artery disease by the NCDR as well as core laboratory) and registry overcall of left main disease (patients deemed to have left main disease by NCDR but no disease by core laboratory). The results are depicted in Figure 2, which demonstrates no statistically significant difference between groups: for death, the 3-year event rate for the concordant group was 11.3% versus 12.7% in the registry overcall group (P=0.21), and for myocardial infarction, 3.7% versus 2.5% (P=0.47). A similar analysis was performed comparing 4 groups based on left main disease agreement (positive concordance, negative concordance, registry overcall, and core laboratory overcall); however, once again no statistically significant differences were found (P=0.30 for death, P=0.41 for myocardial infarction).

Figure 2.

Analysis of clinical outcomes by left main agreement. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier (KM) method for censored data. Follow-up time was administratively censored on December 31, 2008. For myocardial infarction (MI), patients who died were retained in the denominator, that is, these patients were not censored on date of death. The resulting KM curves are interpreted as actual rather than actuarial probabilities. The log-rank test evaluates whether there is difference between the survival curves. A, KM curve for the outcome of death. B, Curve for recurrent MI.

Discussion

There was modest agreement between interpretation of clinical sites of the angiographic disease severity and that of an independent angiographic core laboratory. The sample sizes were large enough to provide excellent stability for the analysis, with relatively narrow 95% confidence intervals. For the patients with significant disagreement in the diagnosis of left main disease, there was no apparent negative effect on the clinical outcomes measures of death and recurrent myocardial infarction. This particular group was selected as a worse-case scenario, where an overcall or undercall could have a significant impact on clinical management and outcome.14–16 Of course, the power of this analysis is limited, and clinical implications are limited by the sampling nature of this study, with all patients slotted for 1 of 2 revascularization strategies.

These findings demonstrate at best moderate consistency between registry data and core laboratory analysis with regard to patients with 2- and 3-vessel coronary artery disease, a cohort of patients where selection of revascularization strategy is imperative. These results expand on smaller previous reports of interobserver variability, such as that seen in the SYNTAX analysis.9,17 Although several studies have demonstrated the superiority of quantitative coronary angiography (QCA),18 these results indicate a modest agreement between independent angiographers in the ASCERT study. Indeed, QCA, which uses image calibration and arterial contour detection to determine the severity of a coronary lesion, has its own limitations, including difficulty with the evaluation of smaller diameter vessels and complex lesion morphology with irregular borders.8,19 Other issues with QCA include the paucity of views generally used to determine vessel diameter stenosis, and the presence of foreshortening on selected views, which may be easily recognized by a human angiographer. The findings of this study complement the recent report by Nallamothu et al,20 who found that physicians tend to overcall lesions in patients receiving PCI compared with a QCA analysis.

The results of this analysis have significant implications for both research and, potentially, clinical practice. Validation of the angiographic data from the NCDR is necessary for a meaningful nationwide study of the optimal revascularization strategy for patients with multivessel coronary artery disease. Beyond the ASCERT study, reliable angiographic interpretation of multivessel disease must be demonstrated to validate appropriateness and outcome studies nationwide that rely on expert angiographic interpretation in conjunction with advanced imaging methods such as intravascular ultrasound, optical coherence tomography, and physiological methods such as fraction flow reserve.

The data and results presented must be interpreted in the context of the study design. The impact that QCA would have on these results is not clear because QCA was not used in the cases evaluated by either the NCDR sites or the angiographic core laboratory. In addition, the analysis of the clinical impact of disagreement in left main disease between registry and core laboratory data may have been hindered by the relatively small sample size of the disagreement group, and therefore may have been underpowered to detect a real difference. Notably, disagreement did seem to be fairly asymmetrical for left main disease. Although interobserver variability, as noted in previous analyses,17,21,22 may account for overall rates of disagreement, it does not explain this asymmetry; however, this finding must be interpreted in the setting of moderate agreement at the vessel-level (left main kappa=0.53, 95% confidence intervals [0.49–0.59]), and a valid conclusion cannot be drawn with relatively few patients in the registry overcall group (n=17). It should be noted that in this cohort a diseased vessel was defined as having ≥50% diameter stenosis, and results may have varied if a 70% diameter stenosis cutoff was used. Finally, generalization of these results to centers that do not participate in the NCDR must be approached with caution because nonstandardized angiograms may not demonstrate the same level of agreement seen in these results.

Conclusions

There was modest agreement between angiographic readings in clinical practice and those from an independent core laboratory. Overcall of left main disease severity within the registry compared with core laboratory measures was not associated with increased or decreased risk of death or myocardial infarction among this subset of patients. Further study will be needed because the implications for patient management are uncertain.

WHAT IS KNOWN

Coronary angiographic interpretation has intraobserver and interobserver variability, which may impact clinical management.

Quantitative coronary angiography is an objective tool used in core laboratories that can aid in angiographic interpretation but does not eliminate observer variability.

Previous studies evaluating the appropriateness of percutaneous coronary intervention include angiographic interpretations that have generally not been independently verified by a core laboratory.

WHAT THE STUDY ADDS

This article demonstrates the level of concordance between the interpretations of coronary angiograms of clinical sites with a centralized angiographic core laboratory.

This article provides a context with which clinicians can interpret percutaneous coronary intervention appropriateness studies and registry data referencing clinical angiographic data that may not be validated by an independent angiographic core laboratory.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by a grant (RC2HL101489) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The primary author reports no conflicts. Dr Peterson has received consulting fees and honoraria from Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Genentech, Boehringer Ingelheim as well as research grants from Eli Lilly and Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Dr Weintraub has received consulting fees and honoraria from Eli Lilly, Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, and Amarin. Dr Gibson has received consulting fees and honoraria from Johnson & Johnson Corp, Bayer Corporation, Ischemix, Inc, BCRI, Sanofi-Aventis Corp, Genentech, Inc, Merck & Co, CSL Behring, Biogen Idec, Daiichi Sankyo, Inc, Bristol Meyer Squibb, The Medicines Company, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Regado Biosciences, Inc, St. Jude Medical Corp., Ortho McNeil, Portola Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, and GlaxoSmithKline, as well as research grants from Lantheus Medical Imaging, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Bayer Corporation, Genentech Inc, Merck & Co, Atrium Medical Systems, Roche Diagnostics, Ikaria, Inc, Portola Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson Corp, Angel Medical Corporation, Volcano Corp, Stealth Peptides, Sanofi-Aventis, Walk Vascular, and St Jude’s Medical, as well as other financial support from UpToDate in Cardiovascular Medicine. All other authors report no conflicts.

References

- 1.Chan PS, Patel MR, Klein LW, Krone RJ, Dehmer GJ, Kennedy K, Nallamothu BK, Weaver WD, Masoudi FA, Rumsfeld JS, Brindis RG, Spertus JA. Appropriateness of percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2011;306:53–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costa RA, Reiber JH. QCA editorial. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;27:155–156. doi: 10.1007/s10554-011-9827-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brener SJ, Haq SA, Bose S, Sacchi TJ. Three-year survival after percutaneous coronary intervention according to appropriateness criteria for revascularization. J Invasive Cardiol. 2009;21:554–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stone GW, Moses JW. Interventional cardiology: how should the appropriateness of PCI be judged? Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8:544–546. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradley SM, Chan PS, Spertus JA, Kennedy KF, Douglas PS, Patel MR, Anderson HV, Ting HH, Rumsfeld JS, Nallamothu BK. Hospital percutaneous coronary intervention appropriateness and in-hospital procedural outcomes: insights from the NCDR. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:290–297. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.966044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marso SP, Teirstein PS, Kereiakes DJ, Moses J, Lasala J, Grantham JA. Percutaneous coronary intervention use in the United States: defining measures of appropriateness. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serruys PW, Morice MC, Kappetein AP, Colombo A, Holmes DR, Mack MJ, Ståhle E, Feldman TE, van den Brand M, Bass EJ, Van Dyck N, Leadley K, Dawkins KD, Mohr FW, SYNTAX Investigators Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:961–972. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ng VG, Lansky AJ. Novel QCA methodologies and angiographic scores. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;27:157–165. doi: 10.1007/s10554-010-9787-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanboga IH, Ekinci M, Isik T, Kurt M, Kaya A, Sevimli S. Reproducibility of syntax score: from core lab to real world. J Interv Cardiol. 2011;24:302–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2011.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weintraub WS, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Weiss JM, O’Brien SM, Peterson ED, Kolm P, Zhang Z, Klein LW, Shaw RE, McKay C, Ritzenthaler LL, Popma JJ, Messenger JC, Shahian DM, Grover FL, Mayer JE, Shewan CM, Garratt KN, Moussa ID, Dangas GD, Edwards FH. Comparative effectiveness of revascularization strategies. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1467–1476. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein LW, Edwards FH, DeLong ER, Ritzenthaler L, Dangas GD, Weintraub WS. ASCERT: the American College of Cardiology Foundation–the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Collaboration on the comparative effectiveness of revascularization strategies. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:124–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weintraub WS, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Weiss JM, Delong ER, Peterson ED, O’Brien SM, Kolm P, Klein LW, Shaw RE, McKay C, Ritzenthaler LL, Popma JJ, Messenger JC, Shahian DM, Grover FL, Mayer JE, Garratt KN, Moussa ID, Edwards FH, Dangas GD. Prediction of long-term mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention in older adults: results from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Circulation. 2012;125:1501–1510. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.066969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shahian DM, O’Brien SM, Sheng S, Grover FL, Mayer JE, Jacobs JP, Weiss JM, Delong ER, Peterson ED, Weintraub WS, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Klein LW, Shaw RE, Garratt KN, Moussa ID, Shewan CM, Dangas GD, Edwards FH. Predictors of long-term survival after coronary artery bypass grafting surgery: results from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database (the ASCERT study) Circulation. 2012;125:1491–1500. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.066902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brennan JM, Dai D, Patel MR, Rao SV, Armstrong EJ, Messenger JC, Curtis JP, Shunk KA, Anstrom KJ, Eisenstein EL, Weintraub WS, Peterson ED, Douglas PS, Hillegass WB. Characteristics and long-term outcomes of percutaneous revascularization of unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis in the United States: a report from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry, 2004 to 2008. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:648–654. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.10.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang HW, Brent BN, Shaw RE. Trends in percutaneous versus surgical revascularization of unprotected left main coronary stenosis in the drug-eluting stent era: a report from the American College of Cardiology-National Cardiovascular Data Registry (ACC-NCDR) Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;68:867–872. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teirstein PS. Percutaneous revascularization is the preferred strategy for patients with significant left main coronary stenosis. Circulation. 2009;119:1021–1033. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.759712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zir LM, Miller SW, Dinsmore RE, Gilbert JP, Harthorne JW. Interobserver variability in coronary angiography. Circulation. 1976;53:627–632. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.53.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farooq V, Brugaletta S, Serruys PW. Contemporary and evolving risk scoring algorithms for percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart. 2011;97:1902–1913. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hermiller JB, Cusma JT, Spero LA, Fortin DF, Harding MB, Bashore TM. Quantitative and qualitative coronary angiographic analysis: review of methods, utility, and limitations. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1992;25:110–131. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1810250207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nallamothu BK, Spertus JA, Lansky AJ, Cohen DJ, Jones PG, Kureshi F, Dehmer GJ, Drozda JP, Jr, Walsh MN, Brush JE, Jr, Koenig GC, Waites TF, Gantt DS, Kichura G, Chazal RA, O’Brien PK, Valentine CM, Rumsfeld JS, Reiber JH, Elmore JG, Krumholz RA, Weaver WD, Krumholz HM. Comparison of clinical interpretation with visual assessment and quantitative coronary angiography in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in contemporary practice: the Assessing Angiography (A2) project. Circulation. 2013;127:1793–1800. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Detre KM, Wright E, Murphy ML, Takaro T. Observer agreement in evaluating coronary angiograms. Circulation. 1975;52:979–986. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.52.6.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trask N, Califf RM, Conley MJ, Kong Y, Peter R, Lee KL, Hackel DB, Wagner GS. Accuracy and interobserver variability of coronary cineangiography: a comparison with postmortem evaluation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1984;3:1145–1154. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(84)80171-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]