Abstract

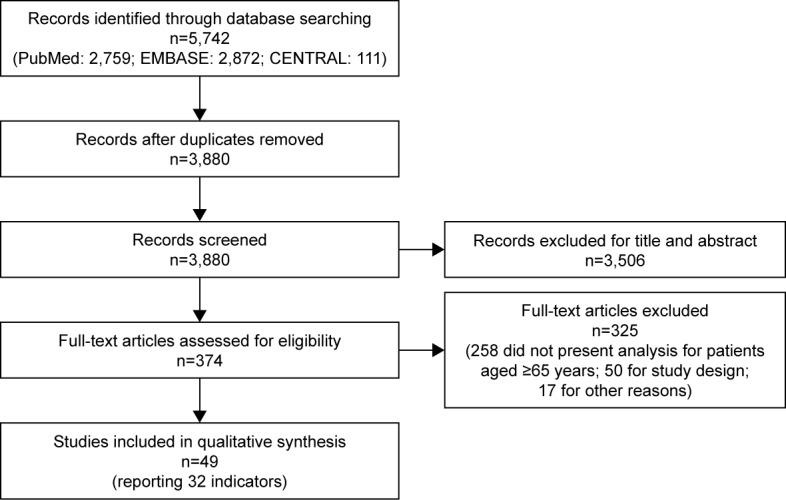

Avoiding medications in which the risks outweigh the benefits in the elderly patient is a challenge for physicians, and different criteria to identify inappropriate prescription (IP) exist to aid prescribers. Definition of IP indicators in the Italian geriatric population affected by cardiovascular disease and chronic comorbidities could be extremely useful for prescribers and could offer advantages from a public health perspective. The purpose of the present study was to identify IP indicators by means of a systematic literature review coupled with consensus criteria. A systematic search of PubMed, EMBASE, and CENTRAL databases was conducted, with the search structured around four themes and combining each with the Boolean operator “and”. The first regarded “prescriptions”, the second “adverse events”, the third “cardiovascular conditions”, and the last was planned to identify studies on “older people”. Two investigators independently reviewed titles, abstracts, full texts, and selected articles addressing IP in the elderly affected by cardiovascular condition using the following inclusion criteria: studies on people aged ≥65 years; studies on patients with no restriction on age but with data on subjects aged ≥65 years; and observational effectiveness studies. The database searches produced 5,742 citations. After removing duplicates, titles and abstracts of 3,880 records were reviewed, and 374 full texts were retrieved that met inclusion criteria. Thus, 49 studies reporting 32 potential IP indicators were included in the study. IP indicators regarded mainly drug–drug interactions, cardio- and cerebrovascular risk, bleeding risk, and gastrointestinal risk; among them, only 19 included at least one study that showed significant results, triggering a potential warning for a specific drug or class of drugs in a specific context. This systematic review demonstrates that both cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular drugs increase the risk of adverse drug reactions in older adults with cardiovascular diseases.

Keywords: inappropriate prescriptions, elderly, cardiovascular diseases, chronic diseases, systematic review

Introduction

The world population is aging at a rapid rate, in high- and low-income countries, challenging health care services from both the organizational and the economic point of view. Throughout the world, the number of people over 60 years doubled in the last century and in Europe, for example, the share of older population is expected to peak at up to 30% by 2050.1 Such epidemiological transition drives the pressing burden of the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases in this age group.2 In addition to the complexities related to the clinical management of older people suffering from multiple chronic diseases, one of the challenges physicians are facing is the consequent complication of complex pharmacological regimens.

Even if the potential benefits of pharmacological therapy are unquestionable, the hazards of negative drug-related outcomes often raise relevant concerns in older adults. Polypharmacy increases the risk of drug–drug and drug–disease interactions, and age-related changes in several physiological characteristics, as well as the presence of chronic illnesses (eg, chronic kidney or liver disease), may affect drugs’ pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Such issues potentially increase the risk of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and explain the significant excess of morbidity, mortality rate, and health care costs within the older population.

In this context, what constitutes an appropriate or inappropriate prescription (IP) in the context of the geriatric population is still debated. Indeed, in order to identify inappropriate pharmacological prescriptions, different criteria have been proposed in recent years. The best known are the Beers criteria,3 the Screening Tool of Older People’s Prescriptions (STOPP), Screening Tool to Alert to Right Treatment (START),4 as well as the Medication Appropriateness Index (MAI),5 and the Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elderly (ACOVE)6 criteria. These criteria and tools are based on expert consensus and are not specifically tailored to any particular disease, even though stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), and other cardiovascular disorders constitute the most frequently treated clinical conditions by physicians in Western countries. Moreover, their impact has not been exhaustively validated toward “hard” end points, and they do not comprise an accurate selection and validation process of drug–drug interactions in light of overlying comorbidities.

Thus, the definition of IP indicators for older adults affected by cardiovascular disease and chronic comorbidities could be extremely useful for the prescriber and might offer advantages from a public health perspective. The aim of the present review was to identify and suggest to the scientific community a list of potential indicators for older adults suffering from cardiovascular diseases and other chronic comorbidities, to be subsequently validated in an ad hoc selected population sample, and eventually proposed as IP indicators. More specifically, we identified all the studies reporting a suspect of drug-related harm in the context of multimorbid older adults suffering from cardiovascular diseases and clustered them according to homogenous groups. Cardiovascular diseases are defined according to the World Health Organization as

a group of disorders of the heart and blood vessels and include coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral arterial disease, rheumatic heart disease, congenital heart disease, and deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.60

Methods

We performed this systematic review in keeping with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews and reported the results according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). The protocol was registered a priori on PROSPERO (N CRD42017057795).

Data source and search strategy

We conducted a systematic search of PubMed, EMBASE, and CENTRAL databases up to October 2, 2014. A librarian (ZM) structured the search on free text and MESH terms with regard to four different domains: “prescriptions”, “adverse events”, “cardiovascular conditions”, and “older people”.

The PubMed search was ((“Drug Prescriptions”[MeSH] OR “Drug Utilization”[MeSH] OR “Adverse Drug Reactions”[tiab] OR “adverse drug events”[tiab] OR “drug safety”[tiab] OR “drug-drug interactions” OR ADRs[tiab] OR “Drug Interactions”[MeSH] OR ((inappropriate*[tiab] OR incorrect*[tiab] OR excess*[tiab] OR harmful*[tiab]) AND (medici*[tiab] OR prescrib*[tiab] OR prescription*[tiab] OR drug*[tiab] OR refill*[tiab] OR claim*[tiab])) OR “Drug-Related Side Effects and Adverse Reactions”[Mesh] OR ((“drug induced”[tiab] OR medication*[ti] OR prescription*[tiab]) AND (“adverse effects” [Subheading:NoExp] OR “adverse effects”[tiab] OR “adverse events”[tiab] OR mortality[sh])))) AND (“Cardiovascular Diseases”[Mesh:noexp] OR “Stroke”[MeSH] OR “Arrhythmias, Cardiac”[MeSH] OR “Hypertension”[MeSH] OR “Heart Diseases”[MeSH] OR “Brain Ischemia” [MeSH] OR “Brain Infarction”[MeSH] OR “Myocardial Ischemia”[MeSH] OR “Peripheral Arterial Disease”[MeSH] OR “Angina Pectoris”[MeSH] OR cardiovascular[tiab] OR “heart disease”[tiab] OR “heart diseases”[tiab] OR “coronary disease”[tiab] OR “coronary diseases”[tiab] OR “heart failure”[tiab] OR “cardiac failure”[tiab] OR “all cause mortality” OR cerebrovascular[tiab])) AND (Aged[Mesh] OR “old people”[tiab] OR “older people”[tiab] OR “old age”[tiab] OR “older age”[tiab] OR “older person”[tiab] OR “old person”[tiab] OR geriatric*[tiab] OR elder*[tiab] OR senior*[tiab]).

Identical searches were conducted in EMBASE and CENTRAL databases.

Study selection

Two trained investigators (NL and DLV) independently reviewed titles and abstracts, and excluded papers using the following criteria:

Studies published in languages other than English

Studies on pediatric population

Studies regarding exposures other than drugs

Studies on diseases other than cardiovascular ones (eg, patients with cancer without cardiovascular disease, with Parkinson without cardiovascular disease, and with diabetes without cardiovascular disease)

Non-outcome studies.

The same investigators independently reviewed full texts and selected articles addressing inappropriate prescribing in elderly patients affected by cardiovascular condition using the following inclusion criteria:

Studies on people aged ≥65 years

Studies on patients with no restriction of age but with data on subjects aged ≥65 years

Observational effectiveness studies.

We resolved disagreement by discussion and consensus with a third trained assessor (DLC). Additionally, we reviewed the reference lists of the included studies and previous reviews to identify additional papers that met inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and quality assessment

For each selected study, we extracted the following data: year of publication, study design, drugs, outcomes, country and setting, characteristic of the study population (eg, sample size, age, and gender), information on follow-up, and main results (ie., estimated with corresponding confidence intervals for each outcome) and additional results.

Two investigators (NL and DLC) independently assessed the methodological quality of included studies using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS)7 for case–control and cohort study, the scale proposed by Jadad et al for randomized controlled trials,8 and the following criteria for case-crossover studies and self-controlled case series:

Clearly stated aims

Appropriate methods are used

Well constituted context of the study

Clearly described, valid, and reliable results

Clearly described analysis

Possible influences of the outcome are considered

Conclusion is linked to the aim, analysis, and interpretation of results of the study

Limitations on research are identified.

Results

The PRISMA flow diagram of study selection is shown in Figure 1. The database search produced 5,742 citations. After removal of duplicates, we reviewed titles and abstracts of 3880 records, among which 374 met the inclusion criteria and the corresponding full texts were retrieved and reviewed. Subsequently, 325 studies were removed because they did not present analysis for patients aged ≥65 years (258 papers) and had inappropriate study design (50), or for other reasons (6 were not original studies, 4 were on patients without cardiovascular disease, 2 with no safety outcomes, 2 with efficacy outcomes only, 2 were duplicate publications, and 1 was on exposure other than drug).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Supplementary material reports the characteristics of the 49 selected studies grouped according to 32 homogeneous potential IP indicators.9–57 Briefly, among the selected studies, two investigated bisphosphonates; seven investigated statins alone or in combination with ezetimibe and their interactions with other pharmacological agents (clopidogrel, vitamin K antagonists, and macrolides); eight investigated antipsychotics; one investigated long-acting beta-adrenoceptor agonist (LABAs) and long-acting anticholinergic drugs (LAAs); four regarded antidiabetics; one was on aspirin in association with clopidogrel and enoxaparin; two regarded anticholinergic drugs; one was on donepezil and its interactions with the antibacterial clarithromycin; two regarded calcium channel blockers (CCBs; short-acting nifedipine) and their interaction with Cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) inhibitors; four regarded clopidogrel and its interactions with proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs); three regarded nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID); four regarded oral anticoagulants (OACs); one regarded postmenopausal hormones; one was on opioids; one investigated angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitors; four investigated antidepressants; one investigated cholinesterase inhibitors; one was on benzodiazepines and benzodiazepine-related drugs; and one investigated the angiotensin receptor blocker olmesartan alone or in combination with other antihypertensive drugs.

Among the 32 homogeneous potential IP indicators, only 19 included at least one study that showed significant and direct association with adverse events (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of the 49 articles included in the review based on 32 IP indicators

| First author (country, data source) (quality assessment) | Study design | Outcomes | Characteristics of the population

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | Estimates (95% CI) | |||

| Anticholinergics (no 1) | ||||

| Huang et al25 (China, Longitudinal Health Insurance database of the National Health Insurance Research Database) (NOS 8/9) |

Retrospective cohort study Population: elder people aged >65 Exposure: Potentially inappropriate anticholinergics vs no-potentially inappropriate one (the Anticholinergic Risk Scale was the criterion) |

(1) Emergency visit (2) Hospitalization (3) Constipation (4) Delirium (5) Cardiac arrhythmia (6) Cognitive impairment |

54,888 vs 17,668 | (1) 1.85 (1.76–1.95) (2) 1.07 (1.01–1.13) (3) 1.87 (1.72–2.03) (4) 1.51 (1.18–1.93) (5) 1.16 (1.05–1.28) |

| In cardiovascular patients (no 2) | ||||

| Uusvaara et al50 (Finland, ad hoc data of previous RCT) (NOS 6/9) |

Prospective cohort study Population: home-dwelling individuals aged 75–90 years with diagnosis of CardioV disease Exposure: patients users of anticholinergic drugs vs nonusers |

(1) Hospitalization (2) Mortality |

295 vs 105 | (1) 2.08 (1.23–3.51) |

| Antidepressants (no 3) | ||||

| Blanchette et al12 (USA, Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey) (NOS 8/9) |

Historical pooled cohort Population: community residents who are ≥65 years Exposure: users of antidepressant (SSRIs or other) vs nonusers |

Acute MI | 1,814 vs 10,856 (1,052 SSRI; 762 others) |

For SSRI: 1.85 (1.13–3.00) |

| Coupland et al15 (UK, supplying data to the QResearch primary care database) (NOS 8/9) |

Cohort study Population: patients with a diagnosis of depression and between the ages of 65 and 100 years Exposure: antidepressants users (TCA, SSRI, others) vs nonusers |

(1) All-cause mortality (2) Attempted suicide/self-harm (3) MI (4) Stroke/transient ischaemic attack (5) Falls (6) Fractures (7) Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (8) Epilepsy/seizures (9) Road traffic accidents (10) ADRs (11) Hyponatraemia |

54,038 vs 6,708 (TCA 21,043; SSRI 29,763; others 3,060) |

For TCA: (1) 1.16 (1.10–1.22) (2) 1.70 (1.28–2.25) (5) 1.30 (1.23–1.38) (6) 1.26 (1.16–1.37) (7) 1.29 (1.10–1.51) For SSRI: (1) 1.54 (1.48–1.59) (2) 2.16 (1.71–2.71) (3) 1.15 (1.04–1.27) (4) 1.17 (1.10–1.26) (5) 1.66 (1.58–1.73) (6) 1.58 (1.48–1.68) (7) 1.22 (1.07–1.40) (8) 1.83 (1.49–2.26) (11) 1.52 (1.33–1.75) For others: (1) 1.66 (1.56–1.77) (2) 5.16 (3.90–6.83) (4) 1.37 (1.22–1.55) (5) 1.39 (1.28–1.52) (6) 1.64 (1.46–1.84) (7) 1.37 (1.08–1.74) (8) 2.24 (1.60–3.15) |

| Zivin et al57 (USA, Veterans Health Administration data) (NOS 7/9) |

Cohort study Population: patients with a diagnosis of depression and at least one citalopram or sertraline prescription Exposure: users of citalopram vs users of sertraline |

(1) Ventricular arrhythmia (2) All-cause mortality (3) Cardiac mortality (4) Non-cardiac mortality |

618,450 vs 365,898 (patients 70–79 years: 71,187 vs 46,585; patients ≥80 years: 54,557 vs 33,487) |

Among patients aged 70–79 years, For citalopram: (1) 5.52 (3.97–7.66) (2) 5.99 (5.30–6.77) (3) 28.60 (18.58–44.03) (4) 4.16 (3.66–4.73) For sertraline: (1) 2.99 (2.13–4.21); (2) 8.22 (6.89–9.82); (3) 23.06 (14.27–37.25); (4) 5.98 (4.94–7.24) Among patients aged ≥80 years, for citalopram: (1) 4.59 (3.28–6.41); (2) 9.96 (8.81–11.25); (3) 54.63 (35.50–84.05); (4) 6.38 (5.62–7.26) For sertraline: (1) 2.75 (1.94–3.90); (2) 13.57 (11.36–16.20); (3) 41.81 (25.88–67.54); (4) 9.33 (7.71–11.3) |

| In CAD patients (no 4) | ||||

| Wu et al55 (Taiwan, National Health Insurance Research database) (Quality Assessment 8/9) |

Case-crossover study Population: patients with a hospitalization for a primary diagnosis of CerebroV event Exposure: users of antipsychotics |

Hospitalization for CerebroV events | 24,214 (16,258 aged ≥65 years) |

Among patients aged 65–75 years: 1.48 (1.30–1.68); Among patients aged ≥75 years: 1.56 (1.37–1.78) |

| Antidiabetics (no 5) | ||||

| Margolis et al37 (UK, The Health Information Network THIN Data) (NOS 7/9) |

Retrospective cohort study Population: patients with at least two records for diabetes and at least 40 years old Exposure: users of insulin or sulfonylureas or biguadine or meglitinide or thiazolidinediones or rosiglitazone or pioglitazone vs nonusers |

Serious atherosclerotic vascular disease of the heart | 63,579 (15,514 patients aged 70–80 years; 6,930 patients aged >80 years) |

Among subjects aged 70–80 years: 3.3 (3.0–3.7) Among subjects aged >80 years: 2.8 (2.5–3.2) |

| Vanasse et al51 (Canada, Québec’s provincial hospital discharge register and Québec’s provincial demographic database) (NOS 6/9) |

Nested case-control study Population: diabetic patients aged ≥65 years Exposure: users of rosiglitazone |

(1) All cause death (2) CV death (3) Hospitalization for acute MI (4) Hospitalization for congestive HF (5) Hospitalization for stroke |

18,335 vs 370,866 4,455 vs 89,037 4,274 vs 85,480 4,274 vs 85,480 4,711 vs 94,209 |

(1) 0.87 (0.76–0.99) (3) 1.41 (1.21–1.65) (4) 1.94 (1.71–2.19) |

| Winkelmayer et al54 (USA, New Jersey Pharmaceutical Assistance for the Aged and Disabled program and the Pennsylvania Pharmaceutical Assistance Contract for Elderly program) (NOS 6/9) |

Inception cohort study Population: people >65 years with state-sponsored prescription drug benefits who had diabetes mellitus Exposure: patients initiated treatment with rosiglitazone vs pioglitazone |

(1) All-cause mortality (2) MI (3) Stroke (4) H ospitalization for congestive HF |

14,101 vs 14,260 | (1) 1.15 (1.05–1.26) (4) 1.13 (1.01–1.26) |

| In end-stage renal disease or disabled patients (no 6) | ||||

| Graham et al22 (USA, Medicare) (NOS 7/9) |

Retrospective cohort study Population: patients aged ≥65 years who have end-stage renal disease or are disabled Exposure: new users of rosiglitazone vs new users of pioglitazone |

(1) Acute MI (2) Stroke (3) HF (4) All-cause mortality (5) Composite end point of acute MI, stroke, HF or death |

67,593 vs 159,978 | (2) 1.27 (1.12–1.45) (3) 1.25 (1.16–1.34) (4) 1.14 (1.05–1.24) (5) 1.18 (1.12–1.23) |

| Antipsychotics (no 7) | ||||

| Franchi et al17 (Italy, Drug Administration database of the Lombardy Region) (NOS 6/9) |

Retrospective case-control study Population: community-dwelling elderly patients aged between 65 and 94 years Exposure: patients who were given at least two consecutive boxes of antipsychotics (any, typical, atypical) |

Hospital discharge diagnosis of CerebroV events | 3,855 vs 15,420 (13,805 patients aged ≥75 years) |

For typical antipsychotics: 2.4 (1.08–5.5) |

| Gisev et al21 (Finland, Finnish National Prescription Register and the Special Reimbursement Register) (NOS 8/9) |

Retrospective cohort study Population: community-dwelling older adults (≥65 years) Exposure: users of antipsychotics vs nonusers |

Mortality | 139 vs 2,085 | 2.07 (1.73–2.47) |

| Pratt et al42 (Australia, Australian Government Department of Veterans’ Affairs administrative claims dataset) (Quality Assessment 8/8) |

Self-controlled case series Population: elderly users of antipsychotics aged ≥65 years Exposure: users of antipsychotic vs nonusers |

Hospitalization for stroke after (1) 1 week (2) 2–4 weeks (3) 5–8 weeks and (4) 8 or more weeks of treatment |

514 typical, 564 atypical vs 9,560 | For typical antipsychotics: (1) 2.25 (1.32–3.83) (3) 1.62 (1.14–2.32) |

| Setoguchi et al48 (USA, General practice database) (NOS 6/9) |

Cohort study Population: British Columbia residents aged ≥65 years who were new users of antipsychotics Exposure: new users of atypical antipsychotics agents vs users of conventional agents |

(1) Overall non-cancer death (2) CardioV death (3) Out-of-hospital CardioV death (4) Infection (including pneumonia) (5) Respiratory disorders (excluding pneumonia) (6) Nervous system disorders (7) Mental disorders (8) Others disorders |

24,359 vs 12,882 | For typical antipsychotics: (1) 1.27 (1.18–1.37) (2) 1.23 (1.10–1.36) (3) 1.36 (1.19–1.56) (5) 1.71 (1.35–2.17) (6) 1.42 (1.01–1.86) (8) 1.27 (1.07–1.51) |

| Vasilyeva et al52 (Canada, Manitoba Population Health Research Data Repository) (NOS 7/9) |

Retrospective cohort study Population: residents in Manitoba aged ≥65 years treated with antipsychotics for the first time Exposure: users of first or second generation antipsychotics |

(1) CerebroV events (2) MI (3) Cardiac arrhythmia (4) Congestive HF (5) Mortality |

4,655 vs 7,779 | For atypical antipsychotics: (2) 1.61 (1.02–2.54) |

| In dementia patients (no 8) | ||||

| Chan et al14 (Japan, ad hoc data) (NOS 6/9) |

Retrospective cohort study Population: patients with vascular and mixed dementia or Alzheimer disease aged ≥65 years Exposure: users of typical and atypical antipsychotic vs nonusers |

CerebroV events | 72 atypical, 654 typical vs 363 non-user | No association |

| Liperoti et al33 (USA, Systematic Assessment of Geriatric drug use via Epidemiology database) (NOS 6/9) |

Retrospective cohort study Population: nursing homes residents with dementia, aged ≥65 years, who were new users of antipsychotics Exposure: users of conventional antipsychotics vs users of atypical ones |

All cause-mortality | 6,524 vs 3,205 | For typical antipsychotics: 1.26 (1.13–1.42) |

| Pariente et al39 (Canada, Public prescription drug and medical services coverage programs databases) (NOS 7/9) |

Retrospective cohort study Population: community-dwelling elderly (≥65 years) patients with dementia, who were new users of cholinesterase inhibitors Exposure: incident antipsychotic users vs antipsychotic nonusers |

MI after (1) 30 days (2) 60 days (3) 90 days and (4) 365 days of treatment |

10,969 vs 10,969 (17,532 patients aged ≥75 years) |

(1) 2.19 (1.11–4.32) |

| Aspirin + clopidogrel + enoxaparin in NSTE-ACS patients (no 9) | ||||

| Heer et al24 (Germany, Acute Coronary Syndromes Registry) (NOS 5/9) |

Observational retrospective multicenter study Population: patients with NSTE-ACSs Exposure: users of aspirin + clopidogrel + enoxaparin vs users of aspirin + UFH |

(1) Hospital mortality (2) Non-fatal reinfarction (3) Congestive HF (4) Stroke (5) CABG (6) MACE (7) All bleeding (8) Major bleeding |

2,956 (128 vs 760 patients aged ≥75 years) |

Among subjects aged ≥75 years: (6) 0.44 (0.20–0.96) |

| Atorvastatin + ezetimibe + OAC in AF patients (no 10) | ||||

| Enajat et al16 (the Netherlands, ad hoc data) (Jadad 4/5) |

Randomized double-blind clinical trial Population: patients aged between 69 and 85 years with chronic or paroxysmal AF with blood cholesterol levels between 4.5 and 7.0 mmol/L Exposure: users of OAC + atorvastatin 40 mg/day + ezetimibe 10 mg/day vs users of OAC + Placebo (target INR of 2.5–3.5) |

Major and minor bleeding; intracerebral bleeding; change in median total cholesterol level and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level | 14 vs 17 | No association |

| Benzodiazepines + benzodiazepines-related drugs (no 11) | ||||

| Gisev et al20 (Finland, Finnish National Prescription Register) (NOS 8/9) |

Population-based retrospective cohort study Population: community-dwelling people aged ≥65 years Exposure: users of benzodiazepine + benzodiazepine-related drugs (zoplicone and zolpidem) vs nonusers |

Mortality | 325 vs 1,520 | No association |

| Bisphosphonates | ||||

| In fracture patients (no 12) | ||||

| Abrahamsen et al10 (Denmark, National Hospital Discharge Register and National Prescription Database) (NOS 9/9) |

Register-based restricted cohort study Population: fractures patients Exposure: new users of bisphosphonates vs nonusers |

(1) Probable AF (2) Hospital-treated AF (3) Ischemic stroke (4) MI |

14,302 vs 28,731 | Among subjects aged >75 years: (1) 1.20 (1.07–1.34) (2) 1.17 (1.02–1.34) |

| In women with CKD (no 13) | ||||

| Hartle et al23 (USA, EpicCare, Geisinger Medical Center’s electronic health records) (NOS 8/9) |

Retrospective cohort study Population: women aged 18–88 years who were enrolled for primary care at any Geisinger facility and with baseline CKD Exposure: users of bisphosphonates vs nonusers |

(1) Death (2) Composite major CardioV events |

3,234 vs 6,370 (5,100 patients aged ≥73 years) |

(1) 0.78 (0.66–0.93) |

| CCBs + CYP3A4 inhibitors in hypertensive patients (no 14) | ||||

| Yoshida et al56 (Japan, Administrative database) (NOS 6/9) |

Nested case-control study Population: hypertensive patients treated with CCBs Exposure: users of CCB + CYP3A4 inhibitor or CCB + other drugs (non CYP3A4 inhibitor) vs users of CCBs alone |

ADRs | 17,430 (Patients >70 years old 30 vs 160) |

No association |

| CCBs in hypertensive patients (no 15) | ||||

| Jung et al27 (Korea, Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service database) (Quality Assessment 7/8) |

Observational case-crossover study Population: elderly patients aged ≥65 years with at least one diagnosis of hypertension and at least one prescription of CCBs Exposure: users of nifedipine vs users of other CCBs |

(1) Stroke (total risk) (2) Ischemic stroke (3) Hemorrhagic stroke (4) Intracranial hemorrhage (5) Subarachnoid Hemorrhage |

373/16,069 (5,546 patients aged 70–74 years) |

(1) 2.56 (1.96–3.37) (2) 2.56 (1.89–3.47) (3) 5.16 (2.29–11.66) (4) 3.60 (1.34–9.66) (5) 14.10 (1.84–108.25) |

| Cholinesterase inhibitors in dementia patients (no 16) | ||||

| Gill et al19 (Canada, Ontario administrative healthcare databases) (NOS 689) |

Population-based cohort study Population: community-dwelling patients aged ≥66 years with a prior diagnosis of dementia Exposure: users of cholinesterase inhibitors vs nonusers |

(1) Hospital visits for syncope (2) Hospital visits for bradycardia (3) Permanent pacemaker insertion (4) Hospitalization for hip fracture |

19,803 vs 61,499 | (1) 1.76 (1.57–1.98) (2) 1.69 (1.32–2.15) (3) 1.49 (1.12–2.00) (4) 1.18 (1.04–1.34) |

| Clopidogrel + PPIs (no 17) | ||||

| Juurlink et al28 (Canada, Ontario Public Drug Program) (NOS 7/9) |

Nested case-control study Population: subjects ≥66 years with a prescription of clopidogrel within 3 days after hospital discharge following treatment for acute MI Exposure: users PPIs |

(1) Recurrent MI <90 days (2) Death <90 days (3) Recurrent MI <1 year (4) Death <1 year |

734 vs 2,057 | (1) 1.27 (1.03–1.57) (3) 1.23 (1.01–1.49) |

| Mahabaleshwarkar et al36 (USA, Medicare) (NOS 6/9) |

Nested case-control study Population: subjects ≥65 years who had initiated clopidogrel therapy and with no gap of 30 days or more between clopidogrel prescription fills Exposure: users of PPIs |

(1) Major CardioV events or all-cause mortality (composite) (2) Acute MI (3) Stroke (4) CABG (5) PCI (6) All-cause mortality (7) Any major CardioV events |

9,908 vs 9,908 | (1) 1.26 (1.18–1.34) (6) 1.40 (1.29–1.53) |

| Rassen et al43 (USA, Provincial health care system funded by the British Columbia government, Pharmaceutical Assistance Contract for the Elderly in Pennsylvania and Pharmaceutical Assistance to the Aged and Disabled in New Jersey) (NOS 7/9) |

Cohort study Population: subjects that underwent PCI or hospitalized for ACS and were new users of clopidogrel Exposure: concurrent users of PPIs vs nonusers |

MI hospitalization or death; MI hospitalization; all-cause death; revascularization |

Cohort 1: 1,353 vs 9,038 Cohort 2: 1,352 vs 2,824 Cohort 3: 1,291 vs 2,707 |

No association |

| Rossini et al44 (Italy, Administrative database) (NOS 7/9) |

Observational study Population: patients that underwent PCI and drug-eluting stents implantation treated with aspirin and clopidogrel Exposure: concurrent users of PPIs vs nonusers |

MACE; bleeding; death; any stent thrombosis | 1,158 vs 170 | No association |

| Donepezil + clarithromycin (no 18) | ||||

| Hutson et al26 (Canada, Ontario Provincial healthcare database) (NOS 6/9) |

Nested case-control study Population: residents aged ≥66 years and users of antibacterial agents for respiratory tract infections Exposure: recent users of antibacterial agents |

Hospitalization for CardioV events | 59 vs 295 | No association |

| LABA and LAA in COPD patients (no 19) | ||||

| Gershon et al18 (Canada, Ontario health care database) (NOS 6/9) |

Nested case-control study Population: individuals aged ≥66 with COPD Exposure: new users of inhaled LABAs or LAAs |

(1) Hospitalization or emergency department visit for ACS (2) HF (3) Cardiac arrhytmia (4) Ischemic stroke |

26,628 vs 26,628 | For LAAs: (1) 1.30 (1.04–1.62) (2) 1.31 (1.08–1.60) (4) 0.68 (0.50–0.91) For LABAs: (1) 1.43 (1.08–1.89) (2) 1.42 (1.10–1.83) |

| New ACE inhibitors in AF patients (no 20) | ||||

| Mujib et al38 (USA, Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure) (NOS 7/9) |

Cohort study Population: patients aged ≥65 years with HF and preserved ejection fraction ≥40% Exposure: users of ACE inhibitors vs nonusers |

(1) Composite outcome (all-cause mortality or HF hospitalization) (2) All-cause mortality (3) HF hospitalization (4) All-cause hospitalization |

After propensity score matching: 1,337 vs 1,337 | (1) 0.91 (0.84–0.99) |

| NSAIDs (no 21) | ||||

| Abraham et al9 (USA, Veterans Affairs – Pharmacy Benefits Management) (NOS 8/9) |

Retrospective cohort study Population: veterans >65 years prescribed an NSAID at any Veterans Affairs facility Exposure: users of NSAIDs, NSAIDs + PPIs, coxib, coxib + PPIs, PPIs vs NSAIDs nonusers |

All-cause mortality following (1) Upper GI events (2) MI (3) CerebroV events |

474,495 | (1) 3.3 (2.8–3.4) (2) 10.3 (9.2–11.6) (3) 12.4 (10.9–14.3) |

| Caughey et al13 (Australia, Administrative database) (NOS 7/9) |

Retrospective cohort study Population: Australian veterans with incident dispensing of an NSAIDs Exposure: users of NSAIDs |

(1) All stroke (2) Ischaemic stroke (3) Hemorrhagic stroke |

162,065 | (1) 1.88 (1.70–2.08) (2) 1.90 (1.65–2.18) (3) 2.19 (1.74–2.77) |

| Roumie et al45 (USA, Tennesee Medicaid program) (NOS 7/9) |

Retrospective Observational Study Population: non-institutionalized person aged 35–94 years who did not have evidence of any non-cardiovascular serious medical illness prior to cohort entry Exposure: users of NSAIDs vs nonusers, with CardioV or not |

Hospitalization for acute MI, stroke, or death from coronary heart disease | NSAIDs users with history of CardioV disease: – Colecoxib 1,882 – Rofecoxib 1,354 – Valdecoxib 394 – Ibuprofen 6,236 – Naproxen 7,249 – Indomethacin 1,361 – Diclofenac 496 NSAIDs non–users with history of CardioV disease: 60,784 NSAIDs users without history of CardioV disease: – Colecoxib 7,117 – Rofecoxib 6,840 – Valdecoxib 1,742 – Ibuprofen 44,261 – Naproxen 48,103 – Indomethacin 6,730 – Diclofenac 3,420 NSAIDs non–users without history of CardioV disease: 380,434 |

In patients aged ≥65 years and among subjects without CVD history, for rofecoxib: 1.26 (1.05–1.51) for valdecoxib: 1.40 (1.05–1.87) for indomethacin: 1.57 (1.15–2.14) |

| OACs (no 22) | ||||

| Poli et al41 (Italy, Elderly Patients followed by Italian Centres for Anticoagulation study) (NOS 5/9) |

Multicenter prospective observational study Population: old patients who started vitamin K antagonist treatment after 80 years of age for thromboprophylaxis of AF or venous thromboembolism Exposure: users vitamin K antagonist |

Major bleedings | 4,093 | NA |

| In CAD patients (no 23) | ||||

| Ruiz Ortiz et al46 (Spain, Administrative database) (NOS 7/9) |

Observational study Population: patients aged ≥80 years with non-valvular AF treated Exposure: users of OAC vs nonusers |

(1) Embolic events (2) Severe bleeding (3) All embolic and hemorrhagic events (4) All-cause death |

164 vs 105 (196 patients aged 80–84 years; 57 patients aged 85–89 years; 16 patients aged ≥90 years) |

(1) 0.17 (0.07–0.41) (3) 0.46 (0.25–0.83) (4) 0.52 (0.31–0.88) |

| Tanaka et al49 (Japan, Administrative database) (NOS 2/9) |

Retrospective case-control study Population: patients treated with antithrombotic drugs Exposure: users of OACs |

GI injuries, including gastric ulcers, duodenal ulcers, and hemorrhagic injuries | 172 vs 3,099 (39 vs 156 patients aged 60–69 years; 102 vs 408 patients aged ≥70 years) |

Among patients aged 60–69 years, for clopidogrel: 4.41 (1.56–12.43) for NSAIDs: 4.01 (1.83–8.86) Among patients aged ≥70 years, for low–dose aspirin: 1.91 (1.17–3.16) for clopidogrel: 3.07 (1.62–5.77) for warfarin: 2.45 (1.35–4.43) for NSAIDs: 4.26 (2.65–6.93) |

| Olmesartan medoxomil in hypertensive patients (no 24) | ||||

| Saito et al47 (Japan, ad hoc database) (NOS 2/9) |

Prospective cohort study Population: olmesartan-naïve hypertensive patients aged ≥65 years Exposure: olmesartan alone, in combination with drugs, or by switching from other antihypertensive medications |

Blood pressure; Clinical laboratory tests; ADRs | 550 (280 young-old patients 65–74 years; 270 older-old patients ≥75 years) |

No association |

| Opioids (no 25) | ||||

| Li et al32 (UK, General Practice Research Database) (NOS 6/9) |

Nested case-control study Population: non-cancer pain patients who had a record for at least one opioid prescription Exposure: users of opioids |

MI | 11,693 vs 44,897 | Among patients aged 71–80 years old, for male: 1.46 (1.23–1.75) for female: 1.34 (1.12–1.61) |

| Postmenopausal hormones (no 26) | ||||

| Løkkegaard et al34 (Denmark, Danish Sex Hormone Register Study) (NOS 8/9) |

Retrospective cohort study Population: healthy Danish women aged 51–69 years Exposure: users of hormone therapy vs nonusers |

MI | Patients aged 65–69 years: – Previous use 27,338; – Current use 75,473 |

For patients aged 65–69 years, for past use: 0.77 (0.60–0.99) |

| Statins + clopidogrel in PCI patients (no 27) | ||||

| Blagojevic et al11 (Canada, Health Insurance databases of Quebec) (NOS 6/9) |

Population-based cohort study Population: PCI patients aged ≥66 years and receiving their first post discharge clopidogrel prescription within 5 days of the hospital discharge date Exposure: users of clopidogrel + non-CYP3A4-metabolized statins, or clopidogrel + CYP3A4-metabolized statins vs clopidogrel and no statins |

Death; MI; unstable angina; hospitalization with repeat revascularization; CerebroV events | 8,417 vs 2,074 | No association |

| Statins + macrolides (no 28) | ||||

| Patel et al40 (Canada, Ontario Drug Benefit database, Canadian Institute for health Information Discharge Abstract database, Ontario Health Insurance Plan database, and Registered persons database of Ontario) (NOS 7/9) |

Population-based cohort study Population: continuous statin users >65 years with macrolide antibiotic co-prescription Exposure: users of statin + clarithromycin or erythromycin vs users of statin + azithromycin |

(1) H ospitalization for rhabdomyolysis (2) Hospitalization for acute kidney injury (3) Hospitalization for hyperkalemia (4) All-cause mortality |

75,858 vs 68,478 | (1) 2.17 (1.03 to 4.52) (2) 1.83 (1.52 to 2.19) (4) 1.57 (1.37 to 1.82) |

| Statins | ||||

| In CAD patients (no 29) | ||||

| Kulik et al29 (USA, Medicare, Pennsylvania Pharmaceutical Assistance Contract for the Elderly program, and the New Jersey Pharmaceutical Assistance to the Aged and Disabled program) (NOS 7/9) |

Observational population-based study Population: patients ≥65 years old who had been hospitalized for acute MI or coronary revascularization Exposure: users of statins vs nonusers |

New-onset AF | 8,450 vs 20,638 | 0.90 (0.85–0.96) In PCI cohort: 0.89 (0.82–0.96) In MI cohort: 0.84 (0.76–0.92) |

| Macchia et al35 (Italy, Administrative database) (NOS 7/9) |

Observational retrospective cohort study Population: patients discharged alive with a first diagnosis of MI treated with statins Exposure: users of statins + n–3 PUFA vs users of statins |

(1) All-cause death (2) Death or MI (3) Death or AF (4) Death or congestive HF (5) Death or stroke |

4,302 vs 7,230 (4,812 patients aged ≥70 years) |

(1) 0.59 (0.52–0.66) (3) 0.78 (0.71–0.86) (4) 0.81 (0.74–0.88) (5) 0.66 (0.59–0.74) In paired–matched cohort: (1) 0.63 (0.56–0.72) (3) 0.82 (0.75–0.90) (4) 0.86 (0.79–0.95) (5) 0.65 (0.58–0.73) |

| In COPD patients (no 30) | ||||

| Lawes et al31 (New Zeland, Administrative database) (NOS 7/9) |

Retrospective cohort study Population: patients with 50–80 years discharged from hospital with a first admission of COPD Exposure: users of statins vs nonusers |

All-cause mortality | 596 vs 1,091; (patients aged 70–79: 354 vs 593) |

2.22 (1.60–3.07) |

| In women (no 31) | ||||

| LaCroix et al30 (USA, Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study) (NOS 4/9) |

Prospective Study Population: women aged 65–79 years who did not have frailty at baseline Exposure: users of statin vs nonusers |

Intermediate frailty; Frail | 2,122 vs 23,256 | No association |

| Warfarin + potentially interacting drugs (no 32) | ||||

| Vitry et al53 (Australia, Australian Department of Veterans’ Affairs administrative claims database) (NOS 6/9) |

Retrospective cohort study Population: veterans aged ≥65 years who were new users of warfarin Exposure: users of Warfarin + potentially interacting drugs vs users of warfarin |

Bleeding-related hospitalization | 17,661 | For clopidogrel: 2.23 (1.48–3.36) for clopidogrel + aspirin: 3.44 (1.28–9.23) for amiodarone: 3.33 (1.38–8.00) for antibiotics: 2.34 (1.55–3.54) for macrolides: 3.07 (1.37–6.90) for trimetoprim or cotrimoxazole: 5.08 (2.00–12.88) |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting-enzyme; ACS, acute coronary syndromes; ADR, adverse drug reaction; AF, atrial fibrillation; CardioV, cardiovascular; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CAD, coronary artery disease; CCB, calcium channel blocker; CerebroV, cerebrovascular; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD, CardioV disease; CYP3A4, Cytochrome P450 3A4; GI, gastrointestinal; HF, heart failure; INR, international normalized ratio; LAA, long-acting anticholinergic; LABA, long-acting beta-agonist; MACE, major adverse cardiac events; MI, myocardial infraction; NA, no association; NOS, Newcastle Ottawa Scale; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; NSTE, non-ST segment elevation; OAC, oral anticoagulant; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid; TCA, tricyclic antidepressants; UFH, unfractionated heparin; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

In greater detail, the potentially identified IP indicators were:

Anticholinergics (No 1) were associated with cardiac arrhythmia, constipation, delirium, emergency visit, and hospitalization.

Anticholinergics in cardiovascular patients (No 2) were associated with hospitalization.

Antidepressants (No 3) were associated with attempted suicide/self-harm, epilepsy seizures, falls, fractures, hyponatremia, MI, mortality, stroke/transient ischaemic attack, upper gastrointes tinal bleeding, and ventricular arrhythmia.

Antidepressants in coronary artery disease (CAD) patients (No 4) were associated with cerebrovascular events.

Antidiabetics (No 5) were associated with acute MI, atherosclerotic vascular heart disease, congestive heart failure (HF), and mortality.

Antidiabetics in end-stage renal disease or disabled patients (No 6) were associated with HF, mortality, and stroke.

Typical antipsychotics (No 7) were associated with cardiovascular death, cerebrovascular events, nervous system disorders, non-cancer death, respiratory disorders, and stroke. Atypical antipsychotics were also associated with mortality and MI.

Typical antipsychotics in dementia patients (No 8) were associated with mortality, and MI.

Bisphosphonates in fracture patients (No 12) were associated with atrial fibrillation (AF).

CCBs in hypertensive patients (No 15) were associated with stroke.

Cholinesterase inhibitors in dementia patients (No 16) were associated with bradycardia, hip fractures, permanent pacemaker insertion, and syncope.

Clopidogrel + PPIs (No 17) were associated with MI, major cardiovascular events, and/or all-cause mortality.

LABA and LAA in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients (No 19) were associate with acute coronary syndrome and HF. LAA were also associated with cardiac arrhythmia.

NSAIDs (No 21) were associated with mortality following upper gastrointestinal events, MI and cerebrovascular events, stroke, acute MI or stroke, or death from coronary heart disease.

OACs in CAD patients (No 23) were associated with embolic and hemorrhagic events, gastrointestinal injuries, and mortality.

Opioids (No 25) were associated with MI.

Statins + Macrolides (No 28) were associated with acute kidney injury, mortality, and rhabdomyolysis.

Statins in COPD patients (No 30) were associated with mortality.

Warfarin + potentially interacting drugs (No 32) were associated with bleeding.

Studies had a good quality (NOS: 9 or 8/9, quality assessment: 7 or 8/8, Jadad: 4/5) in 14 out of 49 cases (29%), moderate (NOS: 7 or 6/9) in 30 cases (61%), and low (NOS: <6/9) in 5 cases (10%).

Discussion

The present systematic review led to the selection of 32 groups of studies indicating potential drug-related harm in older people with cardiovascular diseases. Among them, only 19 included at least one study that showed significant and direct association with adverse events, triggering a potential warning for a specific drug or class of drugs in a specific context. According to the authors of the present review, these 19 groups can be deemed as potential indicators of IP in multimorbid older adults affected by cardiovascular diseases.

The optimization of pharmacological therapy is an essential part of the process of care for an older person. In the past 20 years, several expert panels in Canada, the USA, and Europe have developed different sets of criteria useful for making quality assessments of prescribing practices and medication use in older adults and potentially helpful during the process of medication review. The most widely used criteria for inappropriate medications are the Beers criteria,3 initially developed in 1991 in the USA to target nursing home residents and then revised in 1997, 2003, 2012, and most recently in 2015. These criteria include more than 50 medications assigned to one of three possible categories: those that should always be avoided, those that are potentially inappropriate in older adults with particular health conditions or syndromes, and those that should be used with caution. It has been shown that potentially inappropriate medications included in the Beers criteria are associated with poor health outcomes such as confusion, falls, and mortality. Another important set of criteria is represented by START/STOPP4 which were first published in 2008 and last updated in 2014. STOPP criteria identify prescriptions that are potentially inappropriate to use in patients aged ≥65 years, while START criteria list drug therapies that should be considered where no contraindication to prescription exists in the same group of patients. Beers and START/STOPP criteria overlap in several areas, making them able to predict ADRs, but often with different reliability.58,59

The list of indicators provided in the present review is intended as a set of potential indicators of IP that need to be tested in the real world through a validation process based on tailored studies to explore health outcomes in different older populations and across different care settings. Eventually, these validation studies might lead to a structural proposal for a new set of criteria of IP in older adults suffering from multiple chronic conditions and affected by cardiovascular diseases. This systematic review represents the first step in the process of validation of new indicators, granted by the Italian Medicine Agency (AIFA) and carried out by the I-GrADE consortium.

Our list of potential indicators partially overlaps those proposed by the Beers and STOPP criteria. Several drugs highlighted in this review, including anticoagulants, anti-platelet, blood pressure lowering medications, and many psychotropic drugs, are listed by at least one of the aforementioned criteria. However, this can be no more than an indirect comparison, considering that this review specifically focuses on multimorbid older people suffering from cardiovascular diseases. However, when the attention of such criteria is focused on specific conditions, the agreement intensifies. For example, Beers criteria include a section of recommendations valid in specific contexts and make the case of HF. They point out NSAIDs, CCBs, thiazolidinediones, cilostazol, and dronedarone as potentially inappropriate medications in older adults suffering from HF. Interestingly, three out of five of these drugs have been included in our list. Several selection criteria beyond the specific selection of a population affected by cardiovascular diseases, and the decision-making process itself, might explain these and other discrepancies.

Several drugs not recommended for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases (but that have a potential role in determining ADRs in people with heart diseases) have been included in our list. Some of them are proposed here for the first time as potentially inappropriate. For example, in the study from Abrahamsen et al10 bisphosphonates showed a possible correlation with AF in patients with an underling cardiac disease. This finding, considering the high prevalence of both osteoporosis and cardiovascular diseases in the older population, represents an interesting area of future research, especially when considering the broad set of bisphosphonates with different pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics and the actual possibility of replacing these drugs with compounds recently developed for the treatment of osteoporosis, with a more favorable safety profile and good tolerance.

On the other hand, our research underlines the potential harm linked to drugs that have been synthesized and are recommended for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. This is the case of statins whose toxicity, according to a research published in 2013 by Patel et al,40 may be exacerbated when co-prescripted with macrolides (especially clarithromycin and erythromycin). Considering the high frequency of use of both classes of drugs related to the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases in elders and the presence of macrolides in first-line therapy of community-acquired pneumonia – which is in turn a main cause of hospitalization in patients over 65 – it is very important to clarify the possible effect of such a co-prescription. In fact, the natural decline in renal function that accompanies aging may exaggerate the consequences of a rhabdomyolysis with a dramatic increase in the frequency of acute kidney failure and an excess of mortality.

As in the most recent 2015 version of Beers criteria, we took into account some drug–disease or drug–syndrome interactions. Some of them are well known and have been extensively explored in the literature, as is the case for antipsychotics and dementia, while others are completely new (ie., antidiabetics and stage renal disease or disability), thus opening the way to new and interesting knowledge acquisitions or future research areas.

To our knowledge, the present work is the first time a systematic review of studies has reported any kind of association between drug use and ADRs in multimorbid older adults suffering from cardiovascular diseases. However, the results we report should be read keeping in mind some limitations. First, we did not include any study assessing under use of medications, and it is now clear that underprescribing appropriate medications can be as great a concern as is overprescribing. Prescribing strategies that seek to simply limit the overall number of drugs prescribed to older adults in the name of improving quality of care may be seriously misdirected. Second, considering the broad and complex spectrum of scenarios existing when it comes to multimorbid older adults, and the heterogeneity of studies present in the literature, our search strategy might have missed some relevant hits. However, bibliographies of the selected papers were scrutinized in an attempt to reduce such occurrence. Third, the heterogeneity of study methodologies and care settings precludes the direct translation of our findings in definitive criteria of IP. However, this was an a priori assumption that suggests the setting up and running of ad hoc studies aimed at validating the criteria suggested here. Finally, a judgment of appropriateness cannot be issued on the basis of an all-or-nothing principle, but we should consider dose-dependent appropriateness of every drug for every target population. In this regard, none of the possible indicators relates to drug dosage, and we know that drug doses can be a main determinant for adverse drug events. Moreover, older patients often present an increased volume of distribution and a decreased drug clearance, which can prolong drug half-lives and lead to increased plasma drug concentrations. In addition, a decline in hepatic function with advancing age may account for significant variability in drug metabolism among older adults.

Other limitations were the exclusion of studies published in languages other than English and a lack of risk-of-bias assessment while quality of reporting was assumed to be directly related to quality of information.

Conclusion

The correct clinical and pharmacological management of complex older adults requires the availability of reliable tools of risk stratification, outcome prediction, and appropriateness of care. According to the present systematic review, both cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular drugs increase the risk of ADRs in older adults with cardiovascular diseases. As part of the I-GrADE consortium, the authors of the present study propose a list of potential indicators of IP for application in the context of multimorbid older adults suffering from cardiovascular diseases. It is worth passing such potential indicators through a validation process carried out in the real-world older population and across different care settings. This is part of the commitment of I-GrADE, and such a process will eventually lead to the publication of a reliable list of indicators of IP tailored to the aforementioned population. This and other efforts by the scientific community are required in the near future in order to cope with the emergency that stems from the rapid aging of the world population and to eventually provide better and more sustainable care to older adults.

Acknowledgments

*I-GrADE members: Alessandra Bettiol, Niccolò Lombardi, Ersilia Lucenteforte, Alessandro Mugelli, Alfredo Vannacci (University of Florence, Florence), Alessandro Chinellato (ULSS 9 Treviso, Treviso), Stefano Bonassi, Massimo Fini, Cristiana Vitale (IRCCS San Raffaele Pisana, Rome), Roberto Bernabei, Graziano Onder, Davide Liborio Vetrano (Catholic University, Rome), Claudia Bartolini, Rosa Gini, Francesco Lapi, Giuseppe Roberto (ARS Toscana, Florence), Nera Agabiti, Silvia Cascini, Marina Davoli, Ursula Kirchmayer, Chiara Sorge (ASL 1 Rome), Giovanni Corrao, Federico Rea (University of Milano-Bicocca, Milano), Achille Patrizio Caputi, Francesco Giorgianni, Michele Tari, and Gianluca Trifirò (University of Messina, Messina).

Footnotes

Disclosure

EL received research support from the Italian Agency of Drug (AIFA), which is not related to this study. AM received research support from the AIFA, the Italian Ministry for University and Research (MIUR), Gilead, and Menarini. In the past 2 years he has received personal fees as speaker/consultant from Menarini Group, IBSA, Molteni, Angelini, and Pfizer Alliance, none of which are related to this study. GC received research support from the European Community (EC), the European Medicine Agency (EMA), the Italian Agency of Drug (AIFA), and the Italian Ministry of Health, and of University and Research (MIUR). He has taken part in a variety of projects that were funded by pharmaceutical companies (ie, Novartis, GSK, Roche, AMGEN, and BMS). He has also received honoraria as member of the Advisory Board from Roche. None of these is related to this study.

AV, in the past 2 years, has received personal fees as consultant from Molteni, which is not related to this study. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.European Commision Global Europe 2050. 2012. [Accessed July 24, 2017]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/research/social-sciences/pdf/policy_reviews/global-europe-2050-report_en.pdf.

- 2.Calderon-Larranaga A, Vetrano DL, Onder G, et al. Assessing and measuring chronic multimorbidity in the older population: a proposal for its operationalization. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016 Dec 21; doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw233. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.By the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel American Geriatrics society 2015 updated beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227–2246. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, O’Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44(2):213–218. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Samsa GP, et al. A method for assessing drug therapy appropriateness. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(10):1045–1051. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90144-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wenger NS, Roth CP, Shekelle P, ACOVE Investigators Introduction to the assessing care of vulnerable elders-3 quality indicator measurement set. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(Suppl 2):S247–S252. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. [Accessed March 22, 2016]. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 8.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abraham NS, Castillo DL, Hartman C. National mortality following upper gastrointestinal or cardiovascular events in older veterans with recent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28(1):97–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abrahamsen B, Eiken P, Brixen K. Atrial fibrillation in fracture patients treated with oral bisphosphonates. J Intern Med. 2009;265(5):581–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blagojevic A, Delaney JA, Levesque LE, Dendukuri N, Boivin JF, Brophy JM. Investigation of an interaction between statins and clopidogrel after percutaneous coronary intervention: a cohort study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(5):362–369. doi: 10.1002/pds.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blanchette CM, Simoni-Wastila L, Zuckerman IH, Stuart B. A secondary analysis of a duration response association between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use and the risk of acute myocardial infarction in the aging population. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18(4):316–321. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caughey GE, Roughead EE, Pratt N, Killer G, Gilbert AL. Stroke risk and NSAIDs: an Australian population-based study. Med J Aust. 2011;195(9):525–529. doi: 10.5694/mja11.10055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan MC, Chong CS, Wu AY, et al. Antipsychotics and risk of cerebrovascular events in treatment of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia in Hong Kong: a hospital-based, retrospective, cohort study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(4):362–370. doi: 10.1002/gps.2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coupland C, Dhiman P, Morriss R, Arthur A, Barton G, Hippisley-Cox J. Antidepressant use and risk of adverse outcomes in older people: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2011;343:d4551. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Enajat M, Teerenstra S, van Kuilenburg JT, et al. Safety of the combination of intensive cholesterol-lowering therapy with oral anticoagulation medication in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Drugs Aging. 2009;26(7):585–593. doi: 10.2165/10558450-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franchi C, Sequi M, Tettamanti M, et al. Antipsychotics prescription and cerebrovascular events in Italian older persons. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(4):542–545. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3182968fda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gershon A, Croxford R, Calzavara A, et al. Cardiovascular safety of inhaled long-acting bronchodilators in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(13):1175–1185. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gill SS, Anderson GM, Fischer HD, et al. Syncope and its consequences in patients with dementia receiving cholinesterase inhibitors: a population-based cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(9):867–873. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gisev N, Hartikainen S, Chen TF, Korhonen M, Bell JS. Mortality associated with benzodiazepines and benzodiazepine-related drugs among community-dwelling older people in Finland: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56(6):377–381. doi: 10.1177/070674371105600609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gisev N, Hartikainen S, Chen TF, Korhonen M, Bell JS. Effect of comorbidity on the risk of death associated with antipsychotic use among community-dwelling older adults. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(7):1058–1064. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212000117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graham DJ, Ouellet-Hellstrom R, MaCurdy TE, et al. Risk of acute myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, and death in elderly Medicare patients treated with rosiglitazone or pioglitazone. JAMA. 2010;304(4):411–418. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartle JE, Tang X, Kirchner HL, et al. Bisphosphonate therapy, death, and cardiovascular events among female patients with CKD: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(5):636–644. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heer T, Juenger C, Gitt AK, et al. Acute Coronary Syndromes (ACOS) Registry Investigators Efficacy and safety of optimized antithrombotic therapy with aspirin, clopidogrel and enoxaparin in patients with non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndromes in clinical practice. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2009;28(3):325–332. doi: 10.1007/s11239-008-0294-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang KH, Chan YF, Shih HC, Lee CY. Relationship between potentially inappropriate anticholinergic drugs (PIADs) and adverse outcomes among elderly patients in Taiwan. J Food Drug Anal. 2012;20(4):930–937+985. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hutson JR, Fischer HD, Wang X, et al. Use of clarithromycin and adverse cardiovascular events among older patients receiving donepezil: a population-based, nested case-control study. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(3):205–211. doi: 10.2165/11599090-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jung SY, Choi NK, Kim JY, et al. Short-acting nifedipine and risk of stroke in elderly hypertensive patients. Neurology. 2011;77(13):1229–1234. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318230201a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juurlink DN, Gomes T, Ko DT, et al. A population-based study of the drug interaction between proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel. CMAJ. 2009;180(7):713–718. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.082001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kulik A, Singh JP, Levin R, Avorn J, Choudhry NK. Association between statin use and the incidence of atrial fibrillation following hospitalization for coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105(12):1655–1660. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.01.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LaCroix AZ, Gray SL, Aragaki A, et al. Women’s Health Initiative Statin use and incident frailty in women aged 65 years or older: prospective findings from the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(4):369–375. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.4.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawes CM, Thornley S, Young R, et al. Statin use in COPD patients is associated with a reduction in mortality: a national cohort study. Prim Care Respir J. 2012;21(1):35–40. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2011.00095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li L, Setoguchi S, Cabral H, Jick S. Opioid use for noncancer pain and risk of myocardial infarction amongst adults. J Intern Med. 2013;273(5):511–526. doi: 10.1111/joim.12035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liperoti R, Onder G, Landi F, et al. All-cause mortality associated with atypical and conventional antipsychotics among nursing home residents with dementia: a retrospective cohort study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(10):1340–1347. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04597yel. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lokkegaard E, Andreasen AH, Jacobsen RK, Nielsen LH, Agger C, Lidegaard O. Hormone therapy and risk of myocardial infarction: a national register study. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(21):2660–2668. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macchia A, Romero M, D’Ettorre A, Tognoni G, Mariani J. Exploratory analysis on the use of statins with or without n-3 PUFA and major events in patients discharged for acute myocardial infarction: an observational retrospective study. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e62772. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahabaleshwarkar RK, Yang Y, Datar MV, et al. Risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality associated with concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors in elderly patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29(4):315–323. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2013.772051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Margolis DJ, Hoffstad O, Strom BL. Association between serious ischemic cardiac outcomes and medications used to treat diabetes. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17(8):753–759. doi: 10.1002/pds.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mujib M, Patel K, Fonarow GC, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and outcomes in heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Am J Med. 2013;126(5):401–410. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pariente A, Fourrier-Reglat A, Ducruet T, et al. Antipsychotic use and myocardial infarction in older patients with treated dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(8):648–653. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.28. discussion 654–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel AM, Shariff S, Bailey DG, et al. Statin toxicity from macrolide antibiotic coprescription: a population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(12):869–876. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-12-201306180-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Poli D, Antonucci E, Testa S, et al. Bleeding risk in very old patients on vitamin K antagonist treatment: results of a prospective collaborative study on elderly patients followed by Italian Centres for Anticoagulation. Circulation. 2011;124(7):824–829. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.007864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pratt NL, Roughead EE, Ramsay E, Salter A, Ryan P. Risk of hospitalization for stroke associated with antipsychotic use in the elderly: a self-controlled case series. Drugs Aging. 2010;27(11):885–893. doi: 10.2165/11584490-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rassen JA, Choudhry NK, Avorn J, Schneeweiss S. Cardiovascular outcomes and mortality in patients using clopidogrel with proton pump inhibitors after percutaneous coronary intervention or acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2009;120(23):2322–2329. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.873497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rossini R, Capodanno D, Musumeci G, et al. Safety of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors in patients undergoing drug-eluting stent implantation. Coron Artery Dis. 2011;22(3):199–205. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e328343b03a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roumie CL, Choma NN, Kaltenbach L, Mitchel EF, Jr, Arbogast PG, Griffin MR. Non-aspirin NSAIDs, cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and risk for cardiovascular events-stroke, acute myocardial infarction, and death from coronary heart disease. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(11):1053–1063. doi: 10.1002/pds.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruiz Ortiz M, Romo E, Mesa D, et al. Outcomes and safety of anti-thrombotic treatment in patients aged 80 years or older with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(10):1489–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saito I, Kushiro T, Hirata K, et al. The use of olmesartan medoxomil as monotherapy or in combination with other antihypertensive agents in elderly hypertensive patients in Japan. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10(4):272–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07460.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Setoguchi S, Wang PS, Alan Brookhart M, Canning CF, Kaci L, Schneeweiss S. Potential causes of higher mortality in elderly users of conventional and atypical antipsychotic medications. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(9):1644–1650. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanaka M, Tanaka A, Suemaru K, Araki H. The assessment of risk for gastrointestinal injury with anticoagulant and antiplatelet drugs: the possible beneficial effect of eicosapentaenoic Acid for the risk of gastrointestinal injury. Biol Pharm Bull. 2013;36(2):222–227. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b12-00584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Uusvaara J, Pitkala KH, Kautiainen H, Tilvis RS, Strandberg TE. Association of anticholinergic drugs with hospitalization and mortality among older cardiovascular patients: a prospective study. Drugs Aging. 2011;28(2):131–138. doi: 10.2165/11585060-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vanasse A, Carpentier AC, Courteau J, Asghari S. Stroke and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with rosiglitazone use in elderly diabetic patients. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2009;6(2):87–93. doi: 10.1177/1479164109336047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vasilyeva I, Biscontri RG, Enns MW, Metge CJ, Alessi-Severini S. Adverse events in elderly users of antipsychotic pharmacotherapy in the province of Manitoba: a retrospective cohort study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(1):24–30. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31827934a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vitry AI, Roughead EE, Ramsay EN, et al. Major bleeding risk associated with warfarin and co-medications in the elderly population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(10):1057–1063. doi: 10.1002/pds.2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Winkelmayer WC, Setoguchi S, Levin R, Solomon DH. Comparison of cardiovascular outcomes in elderly patients with diabetes who initiated rosiglitazone vs pioglitazone therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(21):2368–2375. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.21.2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu CS, Wang SC, Cheng YC, Gau SS. Association of cerebrovascular events with antidepressant use: a case-crossover study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(5):511–521. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10071064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoshida M, Matsumoto T, Suzuki T, Kitamura S, Mayama T. Effect of concomitant treatment with a CYP3A4 inhibitor and a calcium channel blocker. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17(1):70–75. doi: 10.1002/pds.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zivin K, Pfeiffer PN, Bohnert AS, et al. Evaluation of the FDA warning against prescribing citalopram at doses exceeding 40 mg. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(6):642–650. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12030408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tosato M, Landi F, Martone AM, et al. Potentially inappropriate drug use among hospitalised older adults: results from the CRIME study. Age Ageing. 2014;43(6):767–773. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wallace E, McDowell R, Bennett K, Fahey T, Smith SM. Impact of potentially inappropriate prescribing on adverse drug events, health related quality of life and emergency hospital attendance in older people attending general practice: a prospective cohort study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(2):271–277. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) [webpage on the Internet] World Health Organization; [Accessed September 21, 2017]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/ [Google Scholar]