Abstract

Background

Medication nonadherence is common in the treatment of serious mental illness (SMI) and leads to poor outcomes. The digital medicine system (DMS) objectively measures adherence with oral aripiprazole in near-real time, allowing recognition of adherence issues. This pilot study evaluated the functionality of an integrated call center in optimizing the use of the DMS.

Materials and methods

An 8-week, open-label, single-arm trial at four US sites enrolled adults with bipolar I disorder, major depressive disorder, and schizophrenia on stable oral aripiprazole doses and willing to use the DMS (oral aripiprazole + ingestible event marker [IEM], IEM-detecting skin patch, and software application). Integrated call-center functionality was assessed based on numbers and types of calls. Ingestion adherence with prescribed treatment (aripiprazole + IEM) during good patch wear and proportion of time with good patch wear (days with ≥80% patch data or detected IEM) were also assessed.

Results

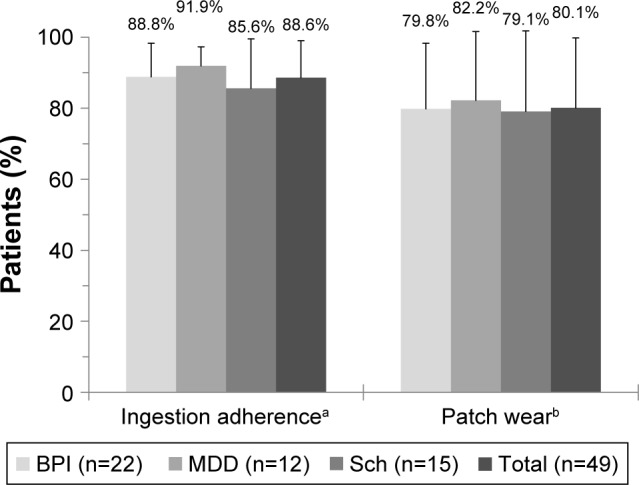

All enrolled patients (n=49) used the DMS and were included in analyses; disease duration overall approached 10 years. For a duration of 8 weeks, 136 calls were made by patients, and a comparable 160 calls were made to patients, demonstrating interactive communication. The mean (SD) number of calls made by patients was 2.8 (3.5). Approximately half of the inbound calls made by patients occurred during the first 2 weeks and were software application- or patch-related. Mean ingestion adherence was 88.6%, and corresponding good patch wear occurred on 80.1% of study days.

Conclusion

In this pilot study, the integrated call center facilitated DMS implementation in patients with SMI on stable doses of oral aripiprazole. In clinical practice, the call center and the DMS will facilitate objective measurement of adherence and potentially improve rates of adherence in patients with SMI.

Keywords: schizophrenia, bipolar I disorder, major depressive disorder, digital medicine, adherence

Plain language summary

Why was the study done? Nonadherence is common in serious mental illness (SMI) and leads to poor outcomes but is difficult to identify. The Digital Medicine System (DMS) was developed to objectively measure nonadherence in near real time so that adherence issues can be proactively recognized and resolved. This pilot study evaluated how well an integrated call center functioned in assisting patients with SMI to use the DMS.

What did the researchers do and find? The frequency and types of calls to and from the integrated call center were measured in an 8-week, open-label, single-arm trial conducted in adults with SMI who were stabilized on oral aripiprazole. Interactive communication was observed between patients and the call center, confirming the call center’s functionality. Most calls were made to resolve issues that patients had when initially using the technology during the first 2 weeks of the study. The observed rate of treatment adherence was higher than that typically reported for patients with SMI.

What do these results mean? The DMS objectively measures adherence in patients with SMI who are stabilized on oral aripiprazole, and an integrated call center can provide functional patient assistance to optimize the use and resulting impact of the DMS.

Introduction

Medication nonadherence is a well-recognized problem in the treatment of serious mental illness (SMI)1–3 and is associated with poor treatment outcomes and increased risk of disease relapse1,3,4 as well as increasing health-care utilization and costs.5,6 Common methods used to assess treatment adherence, whether by direct (eg, pill count) or indirect (eg, patient self-report) means, are known to have limitations.7–9 Even direct measurement of plasma drug levels is limited by cost, lack of established therapeutic concentrations for all drugs, and because a single laboratory assessment may not accurately reflect a patient’s routine adherence pattern (especially for drugs with longer half-lives).7,9 Notably, physician perceptions regarding patient adherence have been shown to overestimate actual medication use,10,11 increasing the risk that treatment decisions will result in suboptimal or adverse outcomes.9 Advancements in the methodologies used to assess adherence could improve health-care provider awareness of patient nonadherence, leading to a proactive medication management approach that could reduce the risk of disease recurrence.

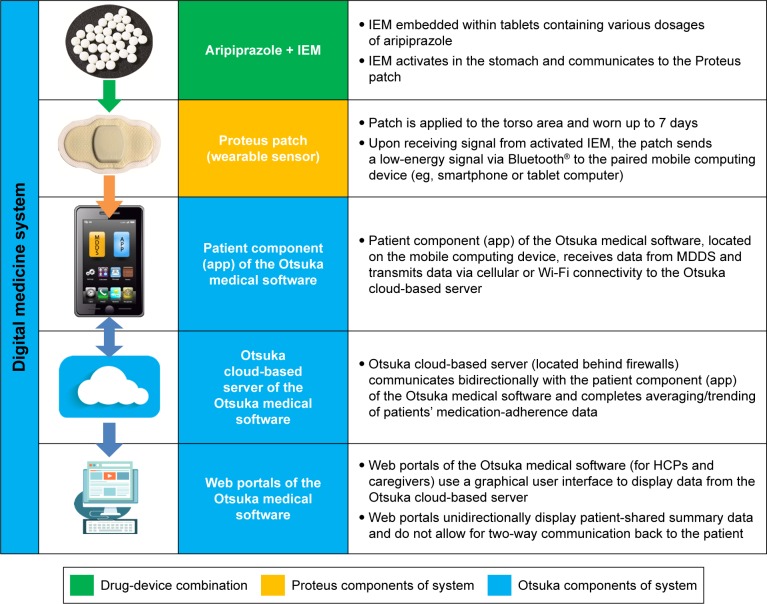

A novel medication adherence-assessment device, the digital medicine system (DMS), was designed to assist health-care providers in objectively assessing patient adherence with oral aripiprazole.12–15 The DMS offers health-care providers timely information on patient adherence, allowing them to intervene early to resolve problems and make more informed treatment decisions. The DMS comprises oral aripiprazole at various dosages embedded with an ingestible event marker (IEM), an accompanying 7-day adhesive patch that detects ingestion of the IEM once activated in the stomach, a medical device data system that receives a signal from the patch, a software application for the patient that transmits adherence data to a secure cloud-based server, and web portals for patient-designated health-care providers and caregivers. Adherence data are accessible to the patient via a mobile app and to their health-care provider and caregiver (with the patient’s consent) via the respective web portals. To protect the security of patient information, access to the DMS and its data transmissions is encrypted using industry-standard methods, and the patient mobile app does not store or display personal information, such as medical diagnoses or medication names.

The DMS improves on existing methods for measuring adherence, such as patient self-report, which is limited by patients’ ability to recall adherence accurately, or prescription refill data, which provide an estimate of the amount of medication a patient has obtained but do not directly assess how much of that medication they have taken.16,17 Because adherence to a scheduled dose is only recorded by the DMS after a patient has actually ingested a tablet, the DMS could offer a more objective and reliable method for measuring adherence.

An integrated call center was established to provide patients with support in using the DMS. The primary objective of this study was to test the functionality of the integrated call center in optimizing use of the DMS by adult patients receiving oral aripiprazole for the treatment of bipolar I disorder (BPI), major depressive disorder, or schizophrenia.

Materials and methods

Study design

A multicenter, open-label, single-arm, pilot trial was conducted at four sites in the US (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02722967). Patients were screened for eligibility for ≤7 days; those meeting study criteria entered an 8-week assessment period consisting of two phases. The first was a 2-week prospective phase during which patients’ DMS use was assessed. Patients who were engaged (defined by the percentage of patch wear by the patient) and wore the DMS patch ≥50% of the time during the 7 days before their week 2 visit continued into a 6-week observation phase. DMS utilization continued to be assessed during this second phase of the assessment period. Primary and exploratory analyses were performed on the intent-to-treat population, which included all patients who entered the trial and used the DMS, including those patients from the 2-week prospective phase who did not continue into the 6-week observation phase. The study concluded with a safety follow-up that occurred 1 week after patients completed the observation phase. Postbaseline study visits occurred at weeks 2, 4, and 8, and the final safety follow-up was done by phone at week 9.

The study was conducted in accordance with International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and institutional review board (Copernicus Group IRB, One Triangle Drive, Suite 100, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA) approval of the study was obtained before enrolling the first participant.

Patients

Adult patients aged 18–65 years with a primary diagnosis of BPI, major depressive disorder, or schizophrenia defined by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-5 criteria and receiving treatment with stable, once-daily oral doses of aripiprazole in the outpatient setting were enrolled. Eligible patients were able to read and understand English and were willing to use and keep a study-provided smartphone containing the DMS software application with them at all times (with satisfactory mobile phone reception or Wi-Fi). Assistance from a caregiver was allowed; however, patients were encouraged to use the DMS independently. All patients had to have an area of skin on the torso that was undamaged (eg, free of any dermatologic problems, such as dermatitis or abrasions) so that the DMS patch could be applied. Patients who were prescribed concomitant antidepressants and/or psychotropic medications were required to have taken stable doses and regimens of those medications for at least 2 weeks and be deemed likely to remain on such therapy during the study.

Patients with DSM-5–defined psychiatric diagnoses other than BPI, major depressive disorder, or schizophrenia (eg, schizoaffective disorder, dementia, an intellectual development disorder, or any diagnosis/condition that might have impaired their ability to participate) were excluded, as were patients with prominent negative symptoms or those with borderline, antisocial, paranoid, schizoid, schizotypal, or histrionic personality disorders. In addition, patients with a positive screen for suicidality on item 4 or 5 of the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale or who were deemed by the investigator to be at serious risk of suicide were not enrolled. Those with underlying medical conditions that would put them at increased risk for adverse events (AEs) or with unstable mood or acute psychotic symptoms at screening that would likely require hospitalization were also excluded.

All patients provided informed consent before participating in any study procedures. Patients were encouraged to use the DMS independently, but could designate a caregiver to assist them if needed. To ensure patient privacy, DMS access information, which was stored on the sponsor’s secure server, and data transmission to the cloud-based server were protected using industry-standard encryption protocols. In addition, no medical diagnoses or drug names were displayed or stored on the patient mobile app. All participants were identified by subject number, initials, and date of birth in the sponsor’s database. No protected health information was obtained or transmitted to the sponsor. In addition, data entered into the patient app were dummy data (ie, email addresses).

DMS and integrated call center

Components of the DMS are shown in Figure 1; Archer IEM and DW5 patch combination with software application version 1.5.3 (Proteus Digital Health, Redwood City, CA; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development and Commercialization, Princeton, NJ, USA) were used (the IEM and wearable patch are 510[k]-cleared devices). Patients received the oral drug–device combination (aripiprazole + IEM) at doses of 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, or 30 mg according to the stable prescribed dose they were taking at screening, although they could have their dose adjusted to another permitted aripiprazole dose during the trial if clinically indicated. The IEM has previously been described in detail.18

Figure 1.

Digital medicine-system components and data communication flow.

Notes: Profit D, Rohatagi S, Zhao C, Hatch A, Docherty JP, Peters-Strickland TS. Developing a digital medicine system in psychiatry: ingestion detection rate and latency period. J Clin Psychiatry. 77(9):e1095–e1100. Copyright 2016, Physicians Postgraduate Press. Adapted by permission.13

Abbreviations: IEM, ingestible event marker; App, application; MDDS, medical device data system; HCPs, health-care professionals.

The patch apparatus consists of an unmedicated sensor patch worn on the patient’s skin (applied to the torso) and an associated compatible software application. Patches were changed every 7 days; they could be changed more frequently to maintain good skin contact. Adherence data from the patch sensor are communicated to a secure server via a software application on a wirelessly connected mobile computing device (eg, a smartphone). The DMS has previously been shown to detect 97% of ingested doses of oral aripiprazole within approximately 1 minute.13

Commercially available smartphones and accessories were provided to patients by study staff at each investigational site, along with basic instructions for use, including the need to charge the battery daily and keep the phone in a location within easy access. A DMS app was loaded on the smartphone, and patients were instructed at each study visit by research coordinators to contact the integrated call center if any technical questions arose.

The integrated call center tracked inbound and outbound calls from and to patients and coordinated feedback to both patients and study sites to optimize use of the DMS. Scheduled outbound calls occurred 48 hours after patients received DMS training at study sites and on day 8 to assess for any difficulties the patient might be having after the first week of DMS use. DMS data, including patch adherence and IEM ingestion, were monitored on a daily basis. The site staff reviewed the dashboard data with the patient during the observation phase at weeks 4 and 8 and discussed any concerns such as poor patch wear or suspected nonadherence. Between clinic visits, the integrated call center reviewed the real-time DMS data daily, and based on predefined triggers contacted the patient, health-care provider, and/or caregiver (if applicable) as needed; this outreach occurred as often as needed to assist in system compliance. More specifically, if the patient did not have a registered pill on the previous day, the patient would receive an “adherence survey” to find out why there was no pill registered. The survey questions had a branching logic depending on patient response. This information was then displayed on the health-care provider dashboard as the reason for no pill registration. The options the patient could choose included such responses as 1) took pill but did not register, 2) forgot to take the pill, and 3) did not want to take the pill. In addition, at the patient visit (and more frequently if needed), the site staff reviewed the data available in the health-care provider dashboard to guide discussions with the patient. If the integrated call center was unable to resolve a technical issue with the DMS, the call was routed to a technology support representative.

The call center was staffed 8 am to 7 pm Central Standard Time (CST) on Monday to Friday and from 8 am to 4 pm CST on Saturday and Sunday. Minimum qualifications for call center agents were completion of Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative human subjects research training and a high school diploma. Call center experience and technical troubleshooting experience were preferred. The average amount of time spent on calls with both health-care providers and subjects was 7 minutes.

Study outcomes and assessments

The primary objective of the study was to evaluate the functionality of an integrated call center in optimizing the use of the DMS by adult patients receiving oral aripiprazole for the treatment of BPI, major depressive disorder, or schizophrenia. More specifically, an integrated call center was established to provide coordinated feedback to the patient and investigative site to optimize use of the DMS. Functionality of the call center was measured by evaluation of information collected during both inbound and outbound calls regarding the type of help needed. The secondary objective was to assess the use of the DMS as measured by the proportion of time during the trial when a patient wore a patch and the proportion of ingested IEMs registered on the digital health data server versus expected IEMs ingested. Ingestion adherence with the prescribed treatment (aripiprazole + IEM) during good patch wear was calculated by dividing the total number of ingested IEMs transmitted to the server by the total number of treatment days with good patch coverage. Patch wear (ie, good patch coverage) was defined as either ≥80% patch data on a given day or a detected IEM within the 24-hour period. The proportion of time patients wore the DMS patch overall was determined by dividing the total time patches were worn by the duration of time a patient was in the study.

Clinical Global Impression – Severity and Personal and Social Performance scale scores were assessed at baseline, and Clinical Global Impression – severity scores were assessed again at week 8. In addition, patients were assessed for AEs and suicidality (using the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale) throughout the trial. A skin irritation scoring system19 was used to grade AEs related to the patch; those of grade ≥2 were considered medically significant.

Statistical methods

Primary and exploratory analyses included all patients who entered the trial and used the DMS (ie, intent-to-treat analysis). Mean Clinical Global Impression – severity scores were determined using last observation carried forward for missing data. The safety analysis also included all enrolled patients who used the DMS. Descriptive statistics were used for baseline demographics and disease characteristics, as well as all study outcomes. The number and proportion of patients with inbound and outbound calls were summarized by type of help for each disease state and overall; exploratory outcomes were also summarized for each disease state and overall.

Results

Patients

Of 51 patients who were screened, 49 met inclusion criteria and were enrolled; all used the DMS and were included in all analyses (Table 1). Following the 2-week prospective phase, 40 of the 49 enrolled patients (81.6%) met criteria for the 6-week observation phase, and 38 of 49 enrolled patients (77.6%) completed the study. Of the 40 patients entering the 6-week observation phase, 38 of 40 (95%) completed the study. Nine of 49 (18.4%) patients discontinued during the prospective phase; inconsistent use of the patch (four of 49 [8.2%]) was the primary reason for withdrawal.

Table 1.

Patient disposition

| Disposition, n (%) | BPI disorder (n=22) |

MDD (n=12) |

Schizophrenia (n=15) |

Total (N=49) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screened | 51 | |||

| Screen failure | 2 | |||

| Enrolled | 22 (100) | 12 (100) | 15 (100) | 49 (100) |

| Treated | 22 (100) | 12 (100) | 15 (100) | 49 (100) |

| Completed | 17 (77.3) | 10 (83.3) | 11 (73.3) | 38 (77.6) |

| Discontinued before observation phasea | 4 (18.2) | 2 (16.7) | 3 (20) | 9 (18.4) |

| Adverse event | 1 (4.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Lost to follow-up | 0 | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Noncompliant with patch wearing | 2 (9.1) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (6.7) | 4 (8.2) |

| Patient decision | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 1 (2) |

| Physician decision | 1 (4.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Otherb | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 1 (2) |

| Discontinued during observation phase | 1 (4.5) | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 2 (4.1) |

| Patient decision | 1 (4.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Otherb | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 1 (2) |

| Analyzed for safetyc | 22 (100) | 12 (100) | 15 (100) | 49 (100) |

| Intent to treatd | 22 (100) | 12 (100) | 15 (100) | 49 (100) |

Notes:

Discontinuations that occurred before the observation phase included those that occurred during the prospective phase;

discontinued due to patch not adhering to skin;

patients who received ≥1 dose of aripiprazole + IEM were included in the safety analysis;

patients who entered the trial and used the DMS. Percentages based on the number of enrolled patients.

Abbreviations: BP, bipolar; MDD, major depressive disorder; DMS, digital medicine system; IEM, ingestible event marker.

The mean (SD) age of the study population was 46.4 (13) years, and most were female (31 of 49 [63.3%]; Table 2). Overall, 95.9% (47 of 49) of the enrolled patients reported using one or more medications prior to the initiation of study treatment, with antidepressants being the most frequently reported class (25 of 49 [51%]). The majority of patients with BPI and major depressive disorder were white (14 of 22 [63.6%] and nine of 12 [75%], respectively), and most with schizophrenia were black (nine of 15 [60%]). Mean (SD) body-mass index across disease states was 35.9 (8.4) kg/m2 (range 21.7–60.9). All patients were fluent in English, and all but four patients had ≥12 years of education.

Table 2.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of enrolled patients

| Characteristics | BPI disorder (n=22) |

MDD (n=12) |

Schizophrenia (n=15) |

Total (n=49) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, years | 45.5 (15.2) | 49.3 (11.2) | 45.5 (11.1) | 46.4 (13) |

| Weight, kg | 99.1 (25.7) | 102.3 (17.9) | 105.5 (25.9) | 101.8 (23.8) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 35 (8.8) | 35.3 (6) | 37.5 (9.7) | 35.9 (8.4) |

| Female, n (%) | 15 (68.2) | 7 (58.3) | 9 (60) | 31 (63.3) |

| Education level, years | 13.7 (2.5) | 15.3 (3.2) | 12.3 (1.8) | 13.7 (2.7) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 14 (63.6) | 9 (75) | 5 (33.3) | 28 (57.1) |

| Black | 7 (31.8) | 2 (16.7) | 9 (60) | 18 (36.7) |

| Asian | 1 (4.5) | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 2 (4.1) |

| Other | 0 | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic, n (%) | 0 | 1 (8.3) | 1 (6.7) | 2 (4.1) |

| English fluency, n (%) | 22 (100) | 12 (100) | 15 (100) | 49 (100) |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Disease duration, years | 8.1 (6.6) | 8.9 (12.4) | 10.9 (11.7) | 9.2 (9.8) |

| CGI-S | 3.2 (1) | 2.4 (0.9) | 3.6 (0.6) | 3.1 (1) |

| PSP | 76.9 (13.6) | 85.1 (12.4) | 69.3 (7) | 76.6 (12.9) |

Note: Values are mean (SD) unless otherwise noted.

Abbreviations: BP, bipolar; MDD, major depressive disorder; BMI, body-mass index; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression – Severity scale; PSP, Personal and Social Performance scale.

The overall duration of disease for enrolled patients approached 10 years (Table 2). Mean (SD) baseline scores on the Clinical Global Impression – severity and Personal and Social Performance scales were 3.1 (1; mildly ill)20 and 76.6 (12.9; mild functional difficulty),21 respectively. Mean (SD) score on Clinical Global Impression – severity at end of study (week 8 or early termination visit) was 2.9 (1.2), and mean (SD) change from baseline was −0.2 (0.7).

Integrated call center activity

Inbound calls

A total of 136 inbound calls overall were made to the integrated call center by approximately three-quarters of patients in the overall study population (36 of 49 [73.5%]) (Table 3); the proportion of patients who made inbound calls was lowest among patients with BPI (14 of 22 [63.6%]). Mean (SD) numbers of calls made by patients in each disease group were 1.5 (1.9), 2.7 (2.9), and 4.7 (4.9) for BPI, major depressive disorder, and schizophrenia, respectively; for the study group overall, this was 2.8 (3.5). The top five reasons for calls were related to the pill status tile on the patient app (20 of 49 patients [40.8%]), account creation (eleven of 49 [22.4%]), issues with the patch (nine of 49 [18.4%]), status icon or patch status on the patient app (nine of 49 [18.4%]), and logging in to the patient app (eight of 49 [16.3%]). Because individual patients may have made more than one call, the number of inbound calls was analyzed by the most frequent issue type overall, and the pill-status tile remained the most common reason for calls (51 of 136 [37.5%]). A little over half of the inbound calls (71 of 136 [52.2%]) from patients occurred during the first 2 weeks of the trial (ie, prospective phase).

Table 3.

Patientsa making and receiving integrated call-center calls during the study, by DMS-related issue type

| n (%) | BPI disorder (n=22) |

MDD (n=12) |

Schizophrenia (n=15) |

Total (n=49) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inbound calls from patients | ||||

| Patient app | ||||

| Account creation | 3 (13.6) | 6 (50) | 2 (13.3) | 11 (22.4) |

| General app questions | 1 (4.5) | 1 (8.3) | 5 (33.3) | 7 (14.3) |

| Logging in | 4 (18.2) | 1 (8.3) | 3 (20) | 8 (16.3) |

| Opening DMS app | 1 (4.5) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (6.7) | 3 (6.1) |

| Patch change | 0 | 0 | 2 (13.3) | 2 (4.1) |

| Patch issues | 2 (9.1) | 3 (25) | 4 (26.7) | 9 (18.4) |

| Patch pair | 0 | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Patch-related | 1 (4.5) | 1 (8.3) | 2 (13.3) | 4 (8.2) |

| Pill registration | 1 (4.5) | 0 | 2 (13.3) | 3 (6.1) |

| Pill-related | 1 (4.5) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (6.7) | 3 (6.1) |

| Pill-status tile | 6 (27.3) | 5 (41.7) | 9 (60) | 20 (40.8) |

| Profile | 1 (4.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Push notification | 0 | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Status of icon or patch | 2 (9.1) | 2 (16.7) | 5 (33.3) | 9 (18.4) |

| HCP portal, connection invitation | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 1 (2) |

| Other | 5 (22.7) | 2 (16.7) | 1 (6.7) | 8 (16.3) |

| Overall | 14 (63.6) | 10 (83.3) | 12 (80) | 36 (73.5) |

| Outbound calls to patients | ||||

| Patient app | ||||

| Account creation | 3 (13.6) | 0 | 0 | 3 (6.1) |

| General app questions | 3 (13.6) | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 4 (8.2) |

| Logging in | 2 (9.1) | 1 (8.3) | 5 (33.3) | 8 (16.3) |

| DMS app | 1 (4.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Opening DMS app | 0 | 1 (8.3) | 1 (6.7) | 2 (4.1) |

| Patch change | 3 (13.6) | 1 (8.3) | 3 (20) | 7 (14.3) |

| Patch issues | 18 (81.8) | 11 (91.7) | 10 (66.7) | 39 (79.6) |

| Pill-related | 5 (22.7) | 5 (41.7) | 5 (33.3) | 15 (30.6) |

| Pill-reminder tile | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 1 (2) |

| Pill-status tile | 6 (27.3) | 4 (33.3) | 2 (13.3) | 12 (24.5) |

| Status of icon or patch | 4 (18.2) | 2 (16.7) | 5 (33.3) | 11 (22.4) |

| Otherb | 14 (63.6) | 9 (75) | 9 (60) | 32 (65.3) |

| Overall | 22 (100) | 12 (100) | 15 (100) | 49 (100) |

Notes:

Intent-to-treat analysis (ie, all patients who entered the trial and used the DMS);

includes planned outbound calls on study days 2 and 8.

Abbreviations: DMS, Digital Medicine System; BP, bipolar; MDD, major depressive disorder; App, application; HCP, health-care provider.

Outbound call reasons

The integrated call center made a total of 257 outbound calls to patients. In addition to the two planned outbound calls on days 2 and 8 (97 scheduled calls made in total; one patient declined to receive the second outbound call), 160 unscheduled calls were triggered by technical or adherence issues the integrated call center identified. Other than the scheduled outbound calls (32 of 49 [65.3%]), the top five reasons for outbound calls overall were patch issues (39 of 49 [79.6%]), pill-related reasons (15 of 49 [30.6%]), pill status tile (12 of 49 [24.5%]), status of icon or patch (eleven of 49 [22.4%]), and logging in (eight of 49 [16.3%]). The most common issues overall by total number of calls, scheduled and unscheduled, were related to the patch (142 of 257 [55.3%]).

Of the unscheduled calls made to patients, the greatest proportion of patients were called to resolve technical issues with the patch (37 of 49 [75.5%]), patient wearing the patch but no registration of ingestion of study drug (17 of 49 [34.7%]), and replacement of the first patch (seven of 49 [14.3%]). There was no notable difference in the reasons for triggered outbound calls among disease types.

DMS use and tolerability

Patients’ mean ingestion adherence was similar across disease types and high overall (88.6% of days; Figure 2). Patients had good patch wear over the duration of the study (80.1% of study days), with no notable differences among disease types (Figure 2). The mean (SD) proportion of patch-wearing time (regardless of good patch wear) appeared similar across disease types and was 77.9% (17.6%) overall (BPI 80.1% [17.3%], major depressive disorder 76.8% [19.7%], schizophrenia 75.6% [17%]).

Figure 2.

Proportion of time over the study period that patients adhered with ingested treatment (oral aripiprazole + ingestible event marker) and had good patch wear (ie, coverage), for each psychiatric diagnosis and the total study population (by intent-to-treat analysis).

Notes: aIngestion adherence defined as total number of ingestible event markers registered on digital health data server as ingested, divided by total number of treatment days with good patch wear during study; bpatch wear (ie, good patch coverage) defined as either ≥80% patch data on a given day or a detected ingestible event marker within the 24-hour period. Bars represent mean, error bars SD; all patients in intent-to-treat population included.

Abbreviations: BP, bipolar; MDD, major depressive disorder; Sch, schizophrenia.

A total of 20 patients (40.8%) experienced treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs), and 17 (34.7%) experienced device-associated TEAEs (Table 4). One patient experienced a mild, nonserious AE of erythema related to the patch (grade 2 on skin-irritation scale), which resolved on discontinuation from the trial; this was the only TEAE resulting in discontinuation from the trial. There were no serious TEAEs or AEs related to suicidality. The most frequent device-associated TEAE was rash (eleven of 49 [22.4%]), and most events were mild in severity. Medically significant patch-related TEAEs occurred in eight patients (16.3%; seven were grade 2, one grade 3). Medication-associated TEAEs also occurred in eight patients (16.3%; Table 4); none was reported for more than two patients or severe.

Table 4.

Device- and medication-associated treatment-emergent AEs

| n (%) | BPI disorder (n=22) |

MDD (n=12) |

Schizophrenia (n=15) |

Total (n=49) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any device-associated AEa | 9 (40.9) | 8 (66.7) | 0 | 17 (34.7) |

| Hyperesthesia | 1 (4.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | ||||

| Rash | 5 (22.7) | 6 (50) | 0 | 11 (22.4) |

| Erythema | 2 (9.1) | 0 | 0 | 2 (4.1) |

| Pruritus | 1 (4.5) | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 2 (4.1) |

| Skin irritation | 0 | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Any medication-associated AEb | 2 (9.1) | 5 (41.7) | 1 (6.7) | 8 (16.3) |

| Nausea | 1 (4.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Peripheral swelling | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 1 (2) |

| Sinusitis | 0 | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 2 (4.1) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 1 (4.5) | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 2 (4.1) |

| Meniscus injury | 0 | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Sunburn | 0 | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Pain in extremity | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 1 (2) |

| Headache | 1 (4.5) | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 2 (4.1) |

| Syncope | 0 | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 1 (2) |

Notes:

Events associated with any part of the Digital Medicine System, except aripiprazole;

events reported as “general” AEs (ie, not device-associated AEs).

Abbreviations: AEs, adverse events; BP, bipolar; MDD, major depressive disorder.

Discussion

The results demonstrated that the integrated call center functioned as intended when implementing DMS use in patients with SMI. The comparable number of calls made to and from patients over the 8-week assessment period in this study shows that the integrated call center successfully established interactive communication with patients. A large proportion of patients made inbound calls (>70%), suggesting that they understood they could obtain assistance from the call center. Furthermore, the interaction between patients and the call center appears to have supported adherence, given that ingestion adherence with oral treatment (88.6%) and the corresponding proportion of days with good patch wear (80.1%) exceeded typical adherence rates of ≤60% based on reports in the literature.1–3 Moreover, the high rate of ingestion adherence in the current study is supported by results from a similar DMS usability study that enrolled 67 patients with schizophrenia.15 Like the current study, patients in the prior DMS study had stable disease, and 70% had a Clinical Global Impression – severity score indicating mild disease. The mean ingestion adherence in the previous study was 73.9%,15 also representing better adherence relative to rates reported in the literature for patients with schizophrenia.1 The higher ingestion adherence observed in the current study compared with that in the prior DMS study suggests that the emphasis on the role of the integrated call center in the current study may have facilitated improved adherence.

Nonadherence to medication is a common concern in SMI1,3,9 that has been shown to contribute to lower rates of treatment response4 and increased hospitalizations and associated costs.22 As a result, expert consensus guidelines highlight the importance of improving adherence in order to prevent relapse, reduce hospitalization and health-care costs, and improve long-term social functioning.9

To avoid unwarranted dosing or medication changes and the potential adverse outcomes that can result when poor adherence is not identified and addressed,23 it is essential that adherence assessments are accurate. Adherence is most often assessed using indirect methods, such as patient and physician reports.8 However, indirect methods have been shown to overestimate actual adherence.10 Other more objective methods may also be inaccurate or unreliable, such as electronic pill trays or pill counts, which are unable to confirm the number of pills that were truly ingested,7 or measurement of plasma drug levels, which can confirm adherence just prior to the assessment, but do not reflect a patient’s daily adherence. Because the DMS addresses daily adherence by detecting and registering the ingestion of actual doses taken by a patient, it provides an alternative and objective means of closely managing medication therapy to ensure adherence and optimal outcomes.

The integrated call center also demonstrated an important role in this trial. Most inbound calls were received during the first 2 weeks of the study, and the most common reasons for calls were related to the pill status tile and account creation, indicating that the call center provided assistance to the overall patient population as they became familiar with use of the DMS. The greater number of calls during the first 2 weeks of the trial also indicates that patients became increasingly comfortable with using the DMS over time. Consistent with the observation that ingestion adherence among patients with schizophrenia was lower in the prior DMS usability study than the current study,15 more than half of the calls in the present study were made by patients with schizophrenia, indicating that this patient group may need or seek more assistance when initiating use of the DMS.

Other common reasons for inbound calls included issues with the patient app. Because patients were provided a smart-phone for study use, some of the patients’ app issues may have occurred as they adjusted to and became familiar with these phones. Patch issues were another common reason for inbound calls, although less than 20% of patients made calls to resolve patch issues. Notably, few patients discontinued before the observation phase because they were unable to comply consistently with using the patch; therefore, it appears that many patients were able to resolve their patch issues with assistance from the integrated call center.

Other than the two planned outbound calls to confirm patient understanding of DMS use, outbound calls from the integrated call center most commonly occurred when patients had technical issues with the patch or were wearing the patch but ingestion of the study drug was not registered. Therefore, the call center demonstrated the potential for early detection of adherence problems and issues related to use of the DMS, likely contributing to the high adherence rate observed, given that the resulting communication with clinicians and patients enabled them to respond to adherence issues proactively. Furthermore, the integrated call center appeared to be effective in helping address technical issues with the DMS, given that the analyses included patients who prematurely withdrew from the trial, yet overall patch wear and ingestion adherence still exceeded commonly reported adherence rates in SMI.1–3

Safety outcomes in this trial were consistent with previous reports.13–15 Notably, patients in this trial had relatively minor issues with use of the DMS patch, a finding that is consistent with previous reports in healthy volunteers.13,14 Identification of appropriate patients who will likely be able to use and benefit from the DMS is an important consideration. As previously noted, patients enrolled in this trial were clinically stable on oral aripiprazole and had the capacity to use the DMS technology and a smartphone. Recognizing the reasons that patients may be nonadherent with treatment is also important. Notably, the current DMS is intended to be of particular use in addressing common factors associated with intentional nonadherence among patients with SMI (ie, patients proactively deciding not to take their medication). However, such issues as forgetfulness and not understanding the need for ongoing treatment24–26 might also be ideally addressed with the DMS by considering the apparatus and inherent interactive adherence-related communication involved with the system, which could serve as a reminder of the need for ongoing treatment and medication taking. This may be an area of future refinement with subsequent versions of the DMS, such that both unintentional and intentional causes of nonadherence can be addressed.

A potential limitation of the trial is the study design feature that required patients to be adherent with the DMS to advance to the observation phase. However, the primary analyses were performed in the intent-to-treat population; therefore, the results reported here reflect the functionality of the DMS in all patients, regardless of whether they demonstrated an acceptable level of adherence during the prospective phase. Nevertheless, the prospective data do show that some patients will not be suitable candidates for the DMS, whether due to underlying disease, lack of technical savvy, or other reasons. The small sample sizes for the individual disease types were an additional limitation. Results in the three diagnosis groups, however, were consistent with the overall findings, suggesting potential broad utility of the DMS and integrated call center in appropriately selected patients with BPI, major depressive disorder, or schizophrenia. More data on specific diagnoses are needed to determine whether there are differences in utility of the DMS across diagnostic categories.

Finally, because this was a prospective clinical trial, it is possible that increased monitoring from study personnel may have contributed to a portion of the interaction between the integrated call center and clinical study sites, although it is unclear to what extent interactions initiated by the study sites may have influenced overall study outcomes (eg, call center use, ingestion adherence, patch wear). When considering the high rate of call activity overall, results from this trial suggest that if implemented in a real-world setting, the integrated call center could provide beneficial assistance to patients initiating the DMS.

Conclusion

Results from this study demonstrate the functionality of an integrated call center in helping remedy issues that can arise during initiation of the DMS in patients with SMI. The DMS and integrated call center provide a proactive and effective means to measure objectively and be alerted to nonadherence, as shown by the types of calls made and overall high ingestion adherence rate observed here. Furthermore, the DMS was relatively well tolerated, with no new safety signals beyond what has been previously reported. Overall, results suggest that the DMS may be a useful tool for patients with SMI on stable doses of oral aripiprazole, and the integrated call center has the potential to be an important facilitator in successful use of the DMS.

Acknowledgments

Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development and Commercialization, Inc. sponsored the study. Editorial support for development of this manuscript was provided by Sheri Arndt at C4 MedSolutions LLC (Yardley, PA), a CHC Group company, and funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development and Commercialization, Inc.

Footnotes

Disclosure

RAB, CZ, CB, EL, and TPS are employees of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development and Commercialization, Inc. AK reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Dolder CR, Leckband SG, Jeste DV. Prevalence of and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(10):892–909. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu X, Chen Y, Faries DE. Adherence and persistence with branded antidepressants and generic SSRIs among managed care patients with major depressive disorder. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;3:63–72. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S17846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sajatovic M, Valenstein M, Blow FC, Ganoczy D, Ignacio RV. Treatment adherence with antipsychotic medications in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(3):232–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindenmayer JP, Liu-Seifert H, Kulkarni PM, et al. Medication nonadherence and treatment outcome in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder with suboptimal prior response. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(7):990–996. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ascher-Svanum H, Zhu B, Faries DE, Furiak NM, Montgomery W. Medication adherence levels and differential use of mental-health services in the treatment of schizophrenia. BMC Res Notes. 2009;2:6. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Offord S, Lin J, Wong B, Mirski D, Baker RA. Impact of oral antipsychotic medication adherence on healthcare resource utilization among schizophrenia patients with Medicare coverage. Community Ment Health J. 2013;49(6):625–629. doi: 10.1007/s10597-013-9638-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kane JM, Kishimoto T, Correll CU. Nonadherence to medication in patients with psychotic disorders: epidemiology, contributing factors and management strategies. World Psychiatry. 2013;12(3):216–226. doi: 10.1002/wps.20060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Velligan DI, Lam YW, Glahn DC, et al. Defining and assessing adherence to oral antipsychotics: a review of the literature. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(4):724–742. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al. The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(Suppl 4):1–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byerly MJ, Thompson A, Carmody T, et al. Validity of electronically monitored medication adherence and conventional adherence measures in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(6):844–847. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.6.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stephenson JJ, Tunceli O, Gu T, et al. Adherence to oral second-generation antipsychotic medications in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: physicians’ perceptions of adherence vs. pharmacy claims. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66(6):565–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02918.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kane JM, Perlis RH, DiCarlo LA, Au-Yeung K, Duong J, Petrides G. First experience with a wireless system incorporating physiologic assessments and direct confirmation of digital tablet ingestions in ambulatory patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):e533–e540. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Profit D, Rohatagi S, Zhao C, Hatch A, Docherty JP, Peters-Strickland TS. Developing a digital medicine system in psychiatry: ingestion detection rate and latency period. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(9):e1095–e1100. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m10643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rohatagi S, Profit D, Hatch A, Zhao C, Docherty JP, Peters-Strickland TS. Optimization of a digital medicine system in psychiatry. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(9):e1101–e1107. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m10693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peters-Strickland T, Pestreich L, Hatch A, et al. Usability of a novel digital medicine system in adults with schizophrenia treated with sensor-embedded tablets of aripiprazole. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:2587–2594. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S116029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shafrin J, Schwartz TT, Lakdawalla DN, Forma FM. Estimating the value of new technologies that provide more accurate drug adherence information to providers for their patients with schizophrenia. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(11):1285–1291. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.11.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valenstein M, Kavanagh J, Lee T, et al. Using a pharmacy-based intervention to improve antipsychotic adherence among patients with serious mental illness. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(4):727–736. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hafezi H, Robertson TL, Moon GD, Au-Yeung KY, Zdeblick MJ, Savage GM. An ingestible sensor for measuring medication adherence. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2015;62(1):99–109. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2014.2341272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Department of Health and Human Services Skin irritation and sensitization testing of generic transdermal drug products. 1999. [Accessed April 25, 2017]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/98fr/990236Gd.pdf.

- 20.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, National Institute of Mental Health, Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs; 1976. Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI) pp. 217–222. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, Ugolini S, Pioli R. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101(4):323–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Svarstad BL, Shireman TI, Sweeney JK. Using drug claims data to assess the relationship of medication adherence with hospitalization and costs. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(6):805–811. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.6.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al. Assessment of adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness: recommendations from the Expert Consensus Guidelines. J Psychiatr Pract. 2010;16(1):34–45. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000367776.96012.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelin K, Lambert T, Jr, Brnabic AJ, et al. Treatment discontinuation and clinical outcomes in the 1-year naturalistic treatment of patients with schizophrenia at risk of treatment nonadherence. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:213–222. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S16800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mert DG, Turgut NH, Kelleci M, Semiz M. Perspectives on reasons of medication nonadherence in psychiatric patients. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:87–93. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S75013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sajatovic M, Levin J, Fuentes-Casiano E, Cassidy KA, Tatsuoka C, Jenkins JH. Illness experience and reasons for nonadherence among individuals with bipolar disorder who are poorly adherent with medication. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52(3):280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]