Abstract

Exposure to chronic stress often elevates basal circulating glucocorticoids during the circadian nadir and leads to exaggerated glucocorticoid production following exposure to subsequent stressors. While glucocorticoid production is primarily mediated by the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, there is evidence that the sympathetic nervous system can affect diurnal glucocorticoid production by direct actions at the adrenal gland. Experiments here were designed to examine the role of the HPA and sympathetic nervous system in enhancing corticosterone production following chronic stress. Rats were exposed to a four-day stress paradigm or control conditions then exposed to acute restraint stress on the fifth day to examine corticosterone and ACTH responses. Repeated stressor exposure resulted in a small increase in corticosterone, but not ACTH, during the circadian nadir, and also resulted in exaggerated corticosterone production 5, 10, and 20 min following restraint stress. While circulating ACTH levels increased after 5 min of restraint, levels were not greater in chronic stress animals compared to controls until following 20 min. Administration of astressin (a CRH antagonist) prior to restraint stress significantly reduced ACTH responses but did not prevent the sensitized corticosterone response in chronic stress animals. In contrast, administration of chlorisondamine (a ganglionic blocker) returned basal corticosterone levels in chronic stress animals to normal levels and reduced early corticosterone production following restraint (up to 10 min) but did not block the exaggerated corticosterone response in chronic stress animals at 20 min. These data indicate that increased sympathetic nervous system tone contributes to elevated basal and rapid glucocorticoid production following chronic stress, but HPA responses likely mediate peak corticosterone responses to stressors of longer duration.

Keywords: HPA axis, Corticosterone, ACTH, CRH, Ganglionic blocker

1. Introduction

Chronic stress causes deleterious health impairments such as depressive-like states (Tafet and Bernardini, 2003; van Praag, 2005), reduction in immune responses (Segerstrom and Miller, 2004), elevated blood pressure (Spruill, 2010), increased blood glucose production (Mathews and Liebenberg, 2012) and metabolic syndrome (Chrousos, 2000; Lamounier-Zepter et al., 2006). Elevated levels of circulating glucocorticoids, primarily corticosterone (in rodents) or cortisol (in humans), during times of stress are implicated in playing a major role in many of these health impairments. Glucocorticoid receptors are widely expressed on cells throughout the body and administration of corticosterone suppresses immune responses, growth hormones, and reproductive hormones (Sapolsky et al., 2000), while chronic administration leads to symptoms of depression (Iijima et al., 2010; Marks et al., 2009) and metabolic syndrome (Karatsoreos et al., 2010). Repeated exposure to stressors often elevate basal corticosterone levels and sensitize corticosterone responses to subsequent exposure to heterotypic stressors (Akana et al., 1992; Bhatnagar and Dallman, 1998; Herman et al., 1995; Johnson et al., 2002) while habituation of corticosterone responses is often observed following repeated exposure to homotypic stressors (Girotti et al., 2006; Sabban and Serova, 2007; Weinberg et al., 2009). Experiments presented here focus on understanding the biological mechanisms by which repeated stressor exposure enhances corticosterone production.

The hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis is viewed as the primary regulator of circulating corticosterone. In response to a stressor, the HPA axis is activated and is critical for the elevation in circulating glucocorticoids. Neurons within the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus release corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) into the hypophyseal portal blood system that then acts upon cells in the anterior pituitary to stimulate the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) into the general circulation. ACTH acts at the adrenal cortex to stimulate corticosterone (or cortisol) production. Repeated stressor exposure alters the regulatory control of the HPA axis in a fashion that enhances corticosterone responses, including: increasing CRH release or secretagogues such as arginine vasopressin (AVP) that increase ACTH production (Herman et al., 1995; Imaki et al., 1991; Kiss and Aguilera, 1993; Makino et al., 1995), increasing excitatory input onto PVN neurons (Flak et al., 2009), altering glutamate and GABAA receptor expression on PVN neurons (Cullinan and Wolfe, 2000; Ziegler et al., 2005), and impairing negative feedback (Buwalda et al., 1999; Greenberg et al., 1989; O’Connor et al., 2003). However, exposure to stressors often result in elevated basal corticosterone during the circadian nadir in the absence of a corresponding increase in circulating ACTH (Johnson et al., 2002; O’Connor et al., 2003; Sterlemann et al., 2008) suggesting other biological system(s) contribute to the regulation of circulating glucocorticoids.

The sympathetic nervous system innervates the adrenal cortex and influences plasma corticosterone production (Engeland and Arnhold, 2005). Stimulation of the splanchnic nerve, the branch of the sympathetic nervous system that innervates the adrenal, increases cortisol secretion in calves and dogs by increasing adrenal sensitivity to ACTH (Edwards and Jones, 1987; Engeland and Gann, 1989). Under normal physiological conditions the contribution of the sympathetic nervous system on circulating glucocorticoid levels appears to be limited to times when HPA responses are extremely low relative to sympathetic responses. For example, during circadian fluctuations when the diurnal amplitude in plasma ACTH is extremely small, splanchnicectomy reduces peak circulating corticosterone levels (Dijkstra et al., 1996; Ulrich-Lai et al., 2006). Another example is following stressors that do not acutely stimulate HPA responses such as dehydration stress when corticosterone responses can again be blocked by splanchnicectomy (Ulrich-Lai and Engeland, 2002).

Repeated stressor exposure often elevates basal sympathetic nervous system tone measured by decreased heart rate variability and elevated circulating epinephrine measured 24 h after the last stressor exposure (Grippo et al., 2002; Remus et al., 2015). Animals exposed to chronic stress also show exaggerated sympathetic nervous system responses to subsequent stressors (Grippo et al., 2002), similar to what is observed with HPA responses. Despite the evidence that the sympathetic nervous system can modulate both basal and stress-induced levels of corticosterone production, there is currently no evidence on whether sympathetic responses contribute to the elevated basal corticosterone or sensitized corticosterone response in chronic stress animals. The current set of experiments tested the hypothesis that the elevated basal corticosterone and sensitized corticosterone response in chronically stressed rats are due, at least in part, to stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and housing

Male Fischer 344 rats were used (Harlan, Indianapolis, Indiana) since this strain is highly stress responsive and susceptible to stress-induced pathology compared to many other rat strains (Camp et al., 2012; Dhabhar et al., 1997; Porterfield et al., 2011; Uchida et al., 2008). Adult animals (250–350 g) were single-housed in standard rat cages, and given access to food and water ad libitum, except when undergoing food restriction stress (see below). Rats were kept on a 12:12 h light–dark cycle (lights on at 0800). All animals were handled according to the Animal Welfare Act and The Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The Kent State University Institutional Animal and Care Committee approved all procedures.

2.2. Chronic stress protocol

Upon arrival, rats were allowed to acclimate to the colony room for 7 days, then handled for 5 consecutive days to acclimate them to the stress of being picked up by research staff. Beginning on day 14 after arrival, rats were either exposed to a 4-day stress protocol, as described previously (Camp et al., 2012), or left undisturbed to serve as home cage controls. Stressors were divided into morning (AM) stressors and evening (PM) stressors. AM stressors were brief (1–3 h) while PM stressors lasted approximately 18 h. AM stressors included: restraint (60 min), foot shock (a total of two 2 s foot shocks delivered over a 30 min period) repeated for two days, and cage tilt (180 min). PM stressors included: food restriction, constant light, and wet bedding. Rats were exposed to stressors in the following order: Day 1: Restraint/Food Deprivation; Day 2: Foot Shock/Constant Light; Day 3: Cage Tilt/Wet Bedding; Day 4: Foot Shock/No PM stressor. Chronic stress paradigms have been shown to alter glucocorticoid responses within a week of initiation of stressor exposure (Bhatnagar and Vining, 2003; Flak et al., 2009; McGuire et al., 2010). This particular stress protocol is sufficient to result in a large number of physiological and behavioral changes that can be measured 24 h after the last stressor including: increased circulating epinephrine (Remus et al., 2015), impaired glucose maintenance (Remus et al., 2015), increased norepinephrine turnover in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex (Porterfield et al., 2012), decreased sucrose intake and preference (Remus et al., 2015), increased consolidation of fearful memories (Camp and Johnson, 2015; Camp et al., 2012), and decreased behavioral inhibition (Camp and Johnson, 2015).

2.3. Acute Restraint Protocol

In the morning on day-5, approximately 24 h after the last stressor, some animals were individually removed from the colony room and exposed to restraint stress in a procedural room across the hall. Animals were gently wrapped in a 38 cm × 45 cm cotton hand towel, and placed under a 5 cm wide Velcro restraint strap attached to a Plexiglas platform that was secured to a bench top. The animals’ tail hung free from the towel to be manipulated for tail vein blood collections. Animals were removed from the colony room to minimize disturbance to the other animals and quickly restrained to obtain an initial blood sample (t = 0). Exposure to restraint stress occurred between 0900 and 1200 h in order to measure corticosterone levels at their circadian nadir.

2.4. Blood collection

For serial blood sampling, animals were restrained and a knick in the tail tip was made using a #11 scalpel blade and approximately 25 μL of whole blood was collected in 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes. In some experiments, rapid decapitations were performed to quickly obtain blood from the trunk. Trunk blood was collected in 7 mL 12 mg EDTA BD Vacutainer ® blood collections tubes (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Blood was placed on ice and plasma was separated from whole blood by centrifuging for 10 min in a refrigerated centrifuge at 4 °C and plasma was collected and stored at −80 °C until ready for analysis.

2.5. Plasma analysis

Corticosterone levels were quantified using a commercially available corticosterone EIA kit (ENZO Life Sciences, Plymouth Meeting, PA). Plasma for corticosterone analysis was diluted at 1:50 in dH2O, and 50 μL of diluted plasma was loaded into each sample well. The detection limit of the assay is 27 pg/ml and the intra-assay and inter-assay coefficient of variation were 7.6% and 15.3% respectively. ACTH levels were quantified using a commercially available ELISA kit (ALPCO, Salem NH). Plasma used to quantify ACTH was not diluted, and 200 μL of plasma was loaded into each sample well. The detection limit of the assay is 0.22 pg/ml and the intra-assay and inter-assay coefficient of variation were 14.8% and 6.6% respectively. In both instances procedures followed the instructions provided by the manufacturer.

2.6. Biotelemetry

Rats were implanted with TR43PB biotelemetry transmitters (Millar Instruments, Houston, TX). Animals were anesthetized under Isoflurane and given an intraperitoneal injection of 2 mg/kg Ketoprofen for pain relief. Animals were shaved and incision sites were cleaned with povidone-iodine antiseptic solution. A mid-line incision was made along the abdominal wall and a sterile transmitter inserted then the abdominal muscle sutured closed. Electrocardiogram (ECG) leads were guided under the skin and sutured into either thoracic muscle over the heart (positive lead) or abdominal muscle along the side (negative lead). Animals were allowed 10 days to recover. Telemetry data were collected and analyzed using ADInstruments PowerLab and LabChart 7. Continuous recordings were collected over a 30 min period and averaged over 5 min blocks for analysis and graphing purposes.

2.7. Study design

2.7.1. Experiment 1

To examine how quickly sensitized corticosterone responses could be observed in chronic stress animals, rats (n = 8/group) were exposed to the chronic stress paradigm described above or remained in the colony room as controls. On day-5, rats were placed in an acute restraint device and blood samples were collected at 0, 5, and 10 min after placing the rat in the restraint.

2.7.2. Experiment 2

To examine if the rapid sensitized corticosterone rise observed in chronic stress animals is associated with a corresponding rise in ACTH, additional rats (n = 8–9/group) were exposed to chronic stress or remained in the colony room to serve as controls. On day five, rats were either placed in the acute restraint device for five minutes then decapitated to collect trunk blood or rats were immediately decapitated without prior restraint.

2.7.3. Experiment 3

To further investigate a potential role of ACTH in sensitized CORT responses, rats (n = 6–8/group) were exposed to the chronic stress paradigm or remained in the colony room as control animals. On day five, rats were given injections of the corticotrophin-releasing hormone antagonist astressin (0.3 mg/kg i.p.; American Peptide Company, Sunnyvale, CA) dissolved in sterile injectable-grade saline or an equivalent volume of saline following a previously published protocol (Lutfy et al., 2012), and 1 h later were restrained and tail blood collected after 0 and 5 min of restraint. Approximately 300 μL of whole blood was collected in order to perform ACTH analysis on plasma collected from tail blood. Astressin was chosen because it has previously been shown to suppress stress-induced ACTH levels without affecting sympathetic responses (Uetsuki et al., 2005).

2.7.4. Experiment 4

We investigated the potential contribution of the sympathetic nervous system on stress-induced enhancement in corticosterone. Here, rats (n = 8/group) were given injections of the ganglionic blocker chlorisondamine diiodide (0.5 mg/kg, s.c.; Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in sterile injectable-grade saline or vehicle. Tail blood was collected at 0, 5, and 10 min following the commencement of restraint stress. Rats remained in the restraint device for 20 min at which time they were euthanized by rapid decapitation and trunk blood collected. In order to avoid a sympathetic response from large blood volume loss over four time points only approximately 25–50 μl of blood was collected at each time-point from the tail vein. Analysis of ACTH, which requires a larger volume of plasma than corticosterone analysis, was only performed using trunk blood at 20 min. This dose of chlorisondamine was chosen because it was previously shown to block sympathetic responses (Houghtling and Bayer, 2002). Due to the longer duration of action of this drug that has been shown to having lasting effects that are observed up to 24 h after injection (Maxwell et al., 1956), injections were made at 18:00 h (approximately 15 h prior to acute restraint exposure). This decreased the stress due to handling and injection on the day of acute stress testing, but to verify the duration of chlorisondamine’s actions rats (n = 4) were implanted with ECG electrodes so heart rate could be monitored. Baseline ECG recordings were recorded for 30 min for each animal between 09:00–11:00 h. At 18:00 h, animals were injected i.p. with 0.5 mg/kg chlorisondamine and ECG recordings were taken again between 09:00–11:00 h the next day.

2.8. Statistics

For most experiments a repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) across time was run first. When a significant interaction was observed additional analyses using either one-way or two-way ANOVAs (based on experimental design) at individual time-points were run. For experiments where endocrine factors were only measured at a single time-point, a one-way or two-way ANOVA (based on experimental design) was used to compare groups. Alpha levels were set at 0.05 for all analyses. Statistics were run using IBM SPSS version 22.

3. Results

3.1. Experiment 1

3.1.1. Effects of chronic stress on corticosterone responses

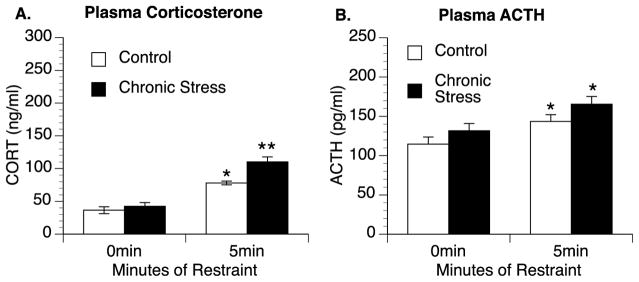

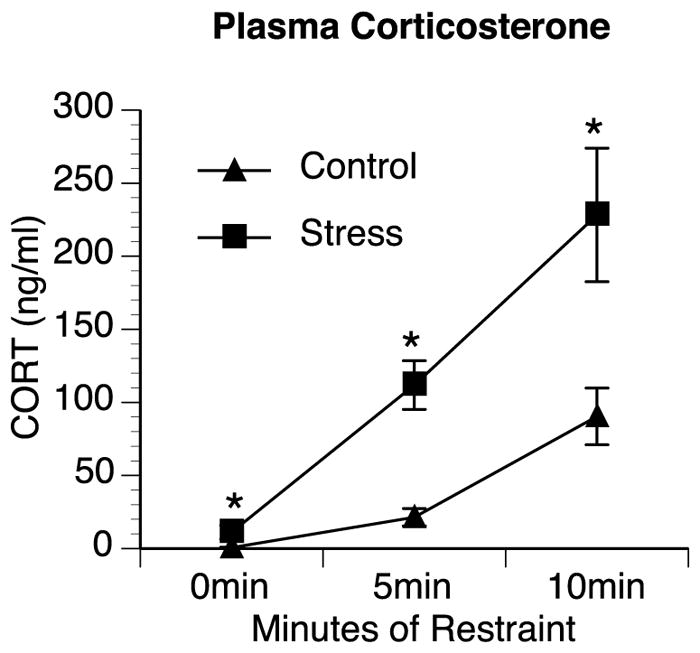

A repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant interaction between treatment group (control vs. chronic stress) and time [F(2,28) = 4.883, p = 0.015] with animals previously exposed to chronic stress having a significantly greater corticosterone response to restraint stress than control animals. Further analyses showed that chronic stress rats had significantly greater plasma corticosterone levels at 0 min (11.2 ng/ml compared to 0.6 ng/ml in control) [F(1,14) = 5.085, p = 0.041], and after 5 min [F(1,14) = 26.173, p < 0.001] and 10 min [F(1,14) = 7.713, p = 0.015] of restraint stress compared to control rats (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Chronic stress elevates basal and enhances stress-induced corticosterone production. Rats exposed to chronic stress (stress) for four days had significantly higher plasma corticosterone (CORT) levels at baseline during the circadian nadir and sensitized corticosterone responses to acute restraint stress at 5 min and 10 min compared to rats that were not previously exposed to stressors (Control). Group means with SEM are graphed. * represents significant differences (p < 0.05) compared to control.

3.2. Experiment 2

3.2.1. Effects of chronic stress on corticosterone and ACTH responses

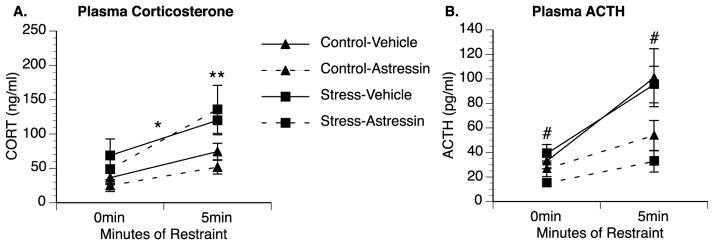

In the previous study, the exaggerated corticosterone response in previously stressed animals was observed as early as 5 min after stressor exposure. To determine if the enhanced corticosterone response corresponded with an enhanced ACTH response, a second group of chronic stress and control animals were rapidly decapitated after either 0 min or 5 min of restraint stress. A 2 × 2 ANOVA analyzing corticosterone levels revealed a significant group by time interaction [F(1,30) = 4.94, p = 0.034] (Fig. 2A). Secondary analysis indicated that there was no significant difference in corticosterone levels between control and chronic stress rats not exposed to restraint (0 min) (p = 0.471). However, rats previously exposed to chronic stress again showed significantly greater corticosterone responses after 5 min of restraint stress compared to control rats [F(1,14) = 12.825, p = 0.001]. A 2 × 2 ANOVA analyzing ACTH levels revealed a significant main effect of acute stressor exposure [F(1,28) = 14.19, p = 0.001], but no significant effect of chronic stressor exposure [F(1,28) = 2.604, p = 0.118] or between-groups interaction [F(1,28) = 0.718, p = 0.404] (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Sensitized corticosterone responses are not accompanied by enhanced ACTH responses in chronic stress animals following 5 min of restraint. Rats exposed to chronic stress for four days had significantly higher plasma corticosterone (CORT) responses after 5 min of acute restraint stress than control rats (A). While restraint stress increased plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in both control and previously stressed rats, the response was not sensitized in chronic stress animals (B). Group means with SEM are graphed. * represents significant differences (p < 0.05) compared to control animals not exposed to acute restraint stress. ** represents significant differences (p < 0.05) compared to control animals exposed to restraint.

3.3. Experiment 3

3.3.1. Effects of CRH blockade on ACTH and CORT in chronic stress animals

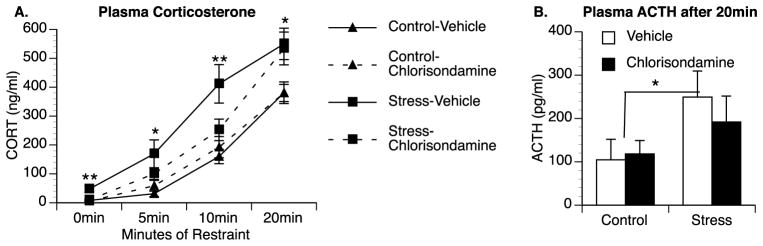

While animals exposed to chronic stress did not have statistically greater ACTH levels compared to control animals following restraint stress in the previous study, there was a trend (p = 0.118) for overall greater ACTH levels in chronic stress animals. To further investigate the possible role of ACTH in mediating the exaggerated corticosterone responses, chronic stress and control animals were administered either vehicle or astressin (CRH antagonist) prior to restraint stress and blood samples were collected at 0 and 5 min. Astressin was previously shown to attenuate ACTH responses to stressors but not affect sympathetic responses measured by heart rate, blood pressure, plasma norepinephrine and plasma epinephrine (Uetsuki et al., 2005). We also observed an attenuated ACTH response in our study; a repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of drug treatment [F(1,25) = 11.006, p = 0.003], such that both control and chronic stress rats administered astressin had lower levels of ACTH than animals given vehicle (Fig. 3B). Similar to our previous experiment, ACTH increased after 5 min of restraint, but there was no interaction with stress condition (p = 0.469) indicating that ACTH increased equally in control and previous stressed animals after 5 min of restraint. ACTH levels were overall lower in this experiment, which may be due to the fact blood samples were collected from a tail vein into 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes compared to trunk blood collected into EDTA coated tubes in experiment 2 (EDTA is a preservative and anticoagulant that likely helps prevent the breakdown of EDTA and preservation of plasma). In contrast to ACTH, a repeated-measures ANOVA analyzing corticosterone levels (Fig. 3A) revealed no significant interaction between drug treatment and time [F(1,25) = 0.031, p = 0.863], but continued to reveal a significant interaction between stress condition and time [F(1,28) = 6.71, p = 0.015] and a main effect of stress condition across both time-points [F(1,28) = 6.03; p = 0.021] indicating previously stressed animals have greater overall corticosterone levels and continue to show enhanced corticosterone responses to restraint compared to control animals. Plasma corticosterone levels at 0 min were slightly higher in this experiment than other experiments possibly because animals were given an injection 1 h prior to blood collection. Basal corticosterone levels were again greater in previously stressed rats (68.8 ng/ml in Stress-Vehicle animals compared to 36.4 ng/ml in Control-Vehicle animals) but this did not reach significance in a two-way ANOVA analyzing corticosterone levels at 0 min (p = 0.121). However, corticosterone levels following 5 min of restraint were significantly greater in previously stressed animals compared to controls [F(1,25) = 8.32, p = 0.007]; there was no effect of drug treatment (p = 0.882) or interaction between stress condition and drug treatment (p = 0.395) at this time.

Fig. 3.

CRH receptor antagonist reduces restraint-induced ACTH responses but does not block sensitized corticosterone responses in previously stressed animals. Rats exposed to chronic stress for four days had significantly higher plasma corticosterone (CORT) responses compared to control rats and injections of 0.3 mg/kg of the CRH-antagonist astressin had no effect on baseline corticosterone or corticosterone levels following 5 min of acute restraint stress (A). In contrast, basal and restraint-induced plasma ACTH levels did not differ between control and chronic stress animals, however, astressin treatment attenuated ACTH levels in both groups (B). Group means with SEM are graphed. * represents significant main effect of chronic stressor exposure (p < 0.05) compared to control animals. # represents significant main effect of drug treatment (p<0.05) compared to vehicle-treated animals.

3.4. Experiment 4

3.4.1. Effects of pharmacological sympathectomy on ACTH and CORT responses in chronic stress animals

To examine the contribution of the sympathetic nervous system on elevated corticosterone levels in chronic stress animals, chronic stress and control animals were administered vehicle or chlorisondamine (a ganglionic blocker) prior to acute restraint stress. A repeated-measures ANOVA revealed that in our experimental design, where chlorisondamine is injected 15 h prior to blood collection, that chlorisondamine significantly reduces heart rate [F(1,6) = 8.14; p = 0.029] (Supplemental Fig. S1). A repeated-measures ANOVA analyzing plasma corticosterone levels revealed a significant effect of stress condition across time [F(3,84) = 3.43, p = 0.045] and a significant interaction between stress condition and drug treatment [F(1,28) = 6.3, p = 0.018] (Fig. 4A). Analysis of 0 min corticosterone levels using a two-way ANOVA also revealed a significant interaction between stress condition and drug treatment [F(1,28) = 7.36; p = 0.011]. Basal corticosterone levels were significantly greater in vehicle-treated animals previously exposed to chronic stress compared to control animals (47.4 ng/ml for Stress-Vehicle animals compared to 8.1 ng/ml for Control-Vehicle animals) (p = 0.008) and this elevation was blocked by pretreatment with chlorisondamine. Following exposure to restraint stress, plasma corticosterone increased more rapidly in animals previously exposed to chronic stress resulting in a significant main effect of chronic stress following 5 min [F(1,28) = 10.184, p = 0.003], 10 min [F(1,28) = 12.416; p = 0.001], and 20 min of restraint [F(1,28) = 12.335; p = 0.002]. Interestingly, chlorisondamine-treatment attenuated the exaggerated corticosterone responses in chronic stress animals at the earlier time-points. While this was not significant at 5 min (p = 0.099) there was a significant interaction between stress condition and drug treatment [F(1,28) = 4.706; p = 0.039] following 10 min of restraint with chlorisondamine treated animals having attenuated plasma corticosterone responses compared to vehicle-treated chronic stress animals. Plasma ACTH levels were also analyzed from trunk blood after 20 min of restraint (Fig. 4B); insufficient amounts of plasma were available from earlier time-points due to the small volume of blood collected during the serial tail vein collection. A 2 × 2 ANOVA revealed significantly greater ACTH levels in animals previously exposed to chronic stress compared to controls [F(1,27) = 4.573, p = 0.042].

Fig. 4.

A ganglionic blocker eliminates the elevation in basal corticosterone and attenuates the rapid corticosterone response following restraint stress in chronic stress animals. Vehicle-treated rats exposed to chronic stress show greater basal and restraint-induced plasma corticosterone levels compared to controls. Injections of 0.5 mg/kg of the ganglionic blocker chlorisondamine reduced baseline corticosterone levels in chronically stressed animals to near control levels and attenuated the rapid increase in corticosterone following restraint stress at 10 min but not following 20 min of restraint (A). Exposure to restraint increase plasma ACTH in both groups but previously stressed animals showed greater elevations in plasma ACTH following 20 min of restraint compared to controls (B). Group means with SEM are graphed. * represents significant main effect of chronic stressor exposure (p < 0.05) compared to control animals. ** represents significant differences between chronic stress animals treated with vehicle compared to chlorisondamine.

4. Discussion

The main findings of this study are (1) repeated exposure to stress often elevates basal corticosterone levels during the circadian nadir and sensitizes corticosterone responses to subsequent stressor exposure (in this case restraint stress); (2) elevated basal corticosterone and rapid corticosterone responses within 5 min are not accompanied by elevated basal or exaggerated ACTH responses; (3) reduction of stress-induced plasma ACTH by administration of a CRH antagonist does not eliminate sensitized corticosterone responses in chronic stress animals; and (4) injection of a ganglionic blocker eliminates the basal elevation in corticosterone in chronic stress animals and attenuates the early sensitized corticosterone response in chronic stress animals. These data compliment previous findings that exposure to chronic stress sensitize corticosterone responses to subsequent acute stressors, and demonstrates enhanced sympathetic nervous system activation also contributes to greater corticosterone levels in chronic stress animals.

The data presented here suggest a greater role for the sympathetic nervous system in regulating stress-induced changes in plasma corticosterone levels than previously appreciated. It has been established that the splanchnic nerve innervates the adrenal gland and can modulate glucocorticoid production (Edwards and Jones, 1987; Engeland and Gann, 1989). Chronic stress is known to increase sympathetic nervous system tone (Grippo et al., 2002; Remus et al., 2015), but the impact this has on glucocorticoid production in chronic stress animals had not been previously investigated. The data presented here indicate that greater sympathetic tone in animals exposed to chronic stress contributes to the elevation in basal corticosterone and rapid increases in corticosterone (within 10 min) following subsequent stressor exposure. Interestingly, chlorisondamine did not block the greater corticosterone response in chronic stress animals at 20 min indicating sympathetic responses do not affect peak corticosterone responses (at least to stressors that persist for longer than 10 min). Greater peak corticosterone levels in chronic stress animals at later time-points are most likely mediated by the combination of greater ACTH production and greater capacity to produce corticosterone due to adrenal hyperplasia and hypertrophy (Ulrich-Lai et al., 2006). The fact that greater corticosterone responses in chronic stress animals at 0 min and at early time-points following stressor exposure are not associated with greater ACTH responses is not necessarily an aberrant finding. Differential activation of ACTH and glucocorticoids has previously been reported and often occur in disease states (Bornstein et al., 2008; Chittiprol et al., 2008; Kern et al., 2014). Greater sympathetic nervous system activation may mediate some of these situations and should be more closely examined.

Animals exposed to chronic stress show a rapid ability to increase plasma corticosterone. Significant elevations in plasma corticosterone levels were consistently measured in chronic stress animals within five minutes of exposure to restraint stress, a time-point when plasma corticosterone were only beginning to increase in control animals and rarely reached significance. In the current set of experiments, we did not explore exactly how quickly elevations in corticosterone levels can be observed in chronic stress animals; however, it is interesting to note that in the one experiment where animals were euthanized by rapid decapitation (experiment 2), we failed to observe a basal increase in plasma corticosterone in chronic stress animals. Thus, it is possible that simply the extra 1–2 min of time it took to restraint an animal and take a blood sample was sufficient to elevate plasma corticosterone and may be responsible for (or contribute to) the elevation in plasma corticosterone in chronic stress animals at t = 0 in experiments where serial blood collections were made.

The mechanism by which chlorisondamine affected glucocorticoid production is not entirely clear. Chlorisondamine is a ganglionic blocker that blocks both sympathetic and parasympathetic responses. There are a number of small molecule neuro-transmitters (e.g., acetylcholine, norepinephrine, epinephrine) and neuropeptides [e.g., vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), neuropeptide Y (NPY), calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), substance P (SP), pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide (PACAP)] that can modulate steroid synthesis in the adrenal gland (Edwards and Jones, 1993). However some of these including, CGRP, SP and PACAP are primarily localized in sensory nerve fibers that do not appear to contribute to splanchnic nerve modulation of steroid production (Ulrich-Lai et al., 2006). One mechanism by which neurotransmitters can affect steroid synthesis is by induction of intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) that upregulates the rate-limiting step, the availability of free cholesterol necessary to synthesis steroids (Hall, 2001). Adrenal cAMP levels express a diurnal rhythm that is maintained in hypophysectomized animals (Guillemant et al., 1980) but reduced following splanchnic nerve transection (Ulrich-Lai et al., 2006) suggesting sympathetic responses may regulate steroid synthesis via modulating cAMP levels and the availability of free cholesterol. Alternatively, chlorisondamine can cause hemodynamic responses such as hypotension that may affect glucocorticoid production or its ability to enter systemic circulation. This would require chlorisondamine to have had different hemodynamic effects in control versus chronic stress animals, since chlorisondamine had no effect on glucocorticoid production in control animals.

Under normal conditions sympathetic responses likely do not significantly contribute to stress-induced corticosterone production as indicated by the fact pharmacological sympathectomy did not reduce stress-induced corticosterone levels in control animals. Presumably this is due to some type of change in the expression of neurotransmitters within the adrenal following chronic stressor exposure. For example, exposure to chronic stress upregulates tyrosine hydroxylase enzymatic activity resulting in greater storage of norepinephrine and epinephrine within the adrenal (McCarty et al., 1988), thus it is possible that medullary ganglion cells in chronic stress animal release greater levels of catecholamines onto adrenal cortical cells that are sufficient to trigger the lower affinity beta adrenergic receptors linked to the activation of adenylate cyclase. Alternatively, neuropeptides classically require greater neural activation to be release compared to small molecule neurotransmitters. Thus, animals exposed to chronic stress may preferentially have greater neuropeptide release within the adrenal and at least VIP is capable of stimulating steroid production even in the presence of fixed ACTH levels (Bloom et al., 1987). Clearly, more research is needed to understand the cellular/molecular mechanism by which sympathetic activation modulates glucocorticoid production.

The biological mechanisms underlying changes in the sympathetic nervous tone following chronic stressor exposure are unknown but may involve brain cytokines. Brain cytokines are soluble proteins that increase in the brain following exposure to chronic or severe acute stressors (Deak et al., 2005; Nguyen et al., 1998; Porterfield et al., 2011) and those actions are thought to mediate many of the deleterious effects associated with stressor exposure including cognitive impairments (Pugh et al., 1999), anxiety (Maier and Watkins, 1995), and depression (Goshen et al., 2008) (Koo and Duman, 2008). We previously reported that central administration of the IL-1 receptor antagonist prior to tailshock stressor exposure blocks the basal elevation in corticosterone 24 h after stressor exposure (Johnson et al., 2004). Additionally, IL-1 receptor type-1 knockout mice do not show elevated basal corticosterone levels following chronic mild stressor exposure (Goshen et al., 2008). Given that both brain IL-1 and sympathetic responses contribute to greater corticosterone following stressor exposure, one possibility is that elevated brain cytokines mediate greater sympathetic tone in animals exposed to chronic or severe acute stressors. There is precedence for brain cytokines to contribute to sympathetic nervous system responses to acute stressors (Engler et al., 2008; Goshen et al., 2008; Goshen and Yirmiya, 2009) but currently is unknown whether elevated brain cytokines mediate greater sympathetic nervous system tone following chronic stressor exposure. This may have important health implications since greater sympathetic responses contribute to hypertension, metabolic disease, pulmonary disorders, and other health impairments.

5. Conclusions

The data presented here demonstrate that the sympathetic nervous system contributes to greater corticosterone production in chronic stress animals compared to naïve controls. Overall, sympathetic responses appear to primarily influence basal circadian levels of corticosterone, while sensitized sympathetic responses are necessary to cause rapid corticosterone responses to subsequent stressors. These data support previous reports that ACTH and glucocorticoid responses can sometimes be disassociated, especially under pathological conditions, and suggest sympathetic responses should be considered as a potential mechanism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Role of funding source

This project was funded by a National Institutes of Health grant (MH099580) who provided funds for the supplies and salary support for Dr. Johnson. Kent State University Postdoctoral Training Fellowship Award provided funds to support the salary and benefits of Dr. Steven Lowrance.

We would like to thank Ankit Patel, M.A., Manuel Rocha, B.S., David Barnard, B.S., Nikita Ascherikin, and Austin Parker for their assistance in handling animals and in the collection of samples. This project was funded by a National Institutes of Health grant (MH099580) and a Kent State University Postdoctoral Training Fellowship Award.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.02.027.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests

The authors have no conflict of interests.

Contributors

Steven A. Lowrance contributed to the study design, collection and analysis of data, and writing the manuscript. Amy Ionadi contributed to the collection of data. Erin McKay contributed to the collection of data. Xavier Douglas contributed to the collection of data. John D. Johnson contributed to the study design, collection and analysis of data, and editing the manuscript.

References

- Akana SF, Dallman MF, Bradbury MJ, Scribner KA, Strack AM, Walker CD. Feedback and facilitation in the adrenocortical system: unmasking facilitation by partial inhibition of the glucocorticoid response to prior stress. Endocrinology. 1992;131:57–68. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.1.1319329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar S, Dallman M. Neuroanatomical basis for facilitation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to a novel stressor after chronic stress. Neuroscience. 1998;84:1025–1039. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00577-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar S, Vining C. Facilitation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to novel stress following repeated social stress using the resident/intruder paradigm. Horm Behav. 2003;43:158–165. doi: 10.1016/s0018-506x(02)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom SR, Edwards AV, Jones CT. Adrenal cortical responses to vasoactive intestinal peptide in conscious hypophysectomized calves. J Physiol. 1987;391:441–450. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein SR, Engeland WC, Ehrhart-Bornstein M, Herman JP. Dissociation of ACTH and glucocorticoids. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2008;19:175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buwalda B, de Boer SF, Schmidt ED, Felszeghy K, Nyakas C, Sgoifo A, Van der Vegt BJ, Tilders FJ, Bohus B, Koolhaas JM. Long-lasting deficient dexamethasone suppression of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical activation following peripheral CRF challenge in socially defeated rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 1999;11:513–520. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1999.00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp RM, Johnson JD. Repeated stressor exposure enhances contextual fear memory in a beta-adrenergic receptor-dependent process and increases impulsivity in a non-beta receptor-dependent fashion. Physiol Behav. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp RM, Remus JL, Kalburgi SN, Porterfield VM, Johnson JD. Fear conditioning can contribute to behavioral changes observed in a repeated stress model. Behav Brain Res. 2012;233:536–544. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chittiprol S, Kumar AM, Satishchandra P, Taranath Shetty K, Bhimasena Rao RS, Subbakrishna DK, Philip M, Satish KS, Ravi Kumar H, Kumar M. Progressive dysregulation of autonomic and HPA axis functions in HIV-1 clade C infection in South India. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrousos GP. The role of stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome: neuro-endocrine and target tissue-related causes. Int J Obesity. 2000;24(Suppl 2):S50–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullinan WE, Wolfe TJ. Chronic stress regulates levels of mRNA transcripts encoding beta subunits of the GABA(A) receptor in the rat stress axis. Brain Res. 2000;887:118–124. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03000-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deak T, Bordner KA, McElderry NK, Barnum CJ, Blandino P, Jr, Deak MM, Tammariello SP. Stress-induced increases in hypothalamic IL-1: a systematic analysis of multiple stressor paradigms. Brain Res Bull. 2005;64:541–556. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhabhar FS, McEwen BS, Spencer RL. Adaptation to prolonged or repeated stress-comparison between rat strains showing intrinsic differences in reactivity to acute stress. Neuroendocrinology. 1997;65:360–368. doi: 10.1159/000127196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra I, Binnekade R, Tilders FJ. Diurnal variation in resting levels of corticosterone is not mediated by variation in adrenal responsiveness to adrenocorticotropin but involves splanchnic nerve integrity. Endocrinology. 1996;137:540–547. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.2.8593800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards AV, Jones CT. The effect of splanchnic nerve section on the sensitivity of the adrenal cortex to adrenocorticotrophin in the calf. J Physiol. 1987;390:23–31. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards AV, Jones CT. Autonomic control of adrenal function. J Anat. 1993;183(Pt. 2):291–307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engeland WC, Arnhold MM. Neural circuitry in the regulation of adrenal corticosterone rhythmicity. Endocrine. 2005;28:325–332. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:28:3:325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engeland WC, Gann DS. Splanchnic nerve stimulation modulates steroid secretion in hypophysectomized dogs. Neuroendocrinology. 1989;50:124–131. doi: 10.1159/000125211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler H, Bailey MT, Engler A, Stiner-Jones LM, Quan N, Sheridan JF. Interleukin-1 receptor type 1-deficient mice fail to develop social stress-associated glucocorticoid resistance in the spleen. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flak JN, Ostrander MM, Tasker JG, Herman JP. Chronic stress-induced neurotransmitter plasticity in the PVN. J Comp Neurol. 2009;517:156–165. doi: 10.1002/cne.22142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girotti M, Pace TW, Gaylord RI, Rubin BA, Herman JP, Spencer RL. Habituation to repeated restraint stress is associated with lack of stress-induced c-fos expression in primary sensory processing areas of the rat brain. Neuroscience. 2006;138:1067–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshen I, Kreisel T, Ben-Menachem-Zidon O, Licht T, Weidenfeld J, Ben-Hur T, Yirmiya R. Brain interleukin-1 mediates chronic stress-induced depression in mice via adrenocortical activation and hippocampal neurogenesis suppression. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:717–728. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg L, Edwards E, Henn FA. Dexamethasone suppression test in helpless rats. Biol Psychiatry. 1989;26:530–532. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(89)90074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grippo AJ, Moffitt JA, Johnson AK. Cardiovascular alterations and autonomic imbalance in an experimental model of depression. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;282:R1333–1341. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00614.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemant J, Guillemant S, Reinberg A. Circadian variation of adrenocortical cyclic nucleotides (cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP) in hypophysectomized rats. Experientia. 1980;36:367–368. doi: 10.1007/BF01952331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall P. Actions of corticotropin on the adrenal cortex: biochemistry and cell biology. In: McEwen BS, editor. Coping with the Environment. Oxford University Press; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Herman JP, Cullinan WE, Morano MI, Akil H, Watson SJ. Contribution of the ventral subiculum to inhibitory regulation of the hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenocortical axis. J Neuroendocrinol. 1995;7:475–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1995.tb00784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghtling RA, Bayer BM. Rapid elevation of plasma interleukin-6 by morphine is dependent on autonomic stimulation of adrenal gland. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;300:213–219. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima M, Ito A, Kurosu S, Chaki S. Pharmacological characterization of repeated corticosterone injection-induced depression model in rats. Brain Res. 2010;1359:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.08.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaki T, Nahan JL, Rivier C, Sawchenko PE, Vale W. Differential regulation of corticotropin-releasing factor mRNA in rat brain regions by glucocorticoids and stress. J Neurosci. 1991;11:585–599. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-03-00585.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JD, O’Connor KA, Deak T, Spencer RL, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Prior stressor exposure primes the HPA axis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2002;27:353–365. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JD, O’Connor KA, Watkins LR, Maier SF. The role of IL-1β in stress-induced sensitization of proinflammatory cytokine and corticosterone responses. Neuroscience. 2004;127:569–577. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karatsoreos IN, Bhagat SM, Bowles NP, Weil ZM, Pfaff DW, McEwen BS. Endocrine and physiological changes in response to chronic corticosterone: a potential model of the metabolic syndrome in mouse. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2117–2127. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern S, Rohleder N, Eisenhofer G, Lange J, Ziemssen T. Time matters – acute stress response and glucocorticoid sensitivity in early multiple sclerosis. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;41:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss A, Aguilera G. Regulation of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis during chronic stress: responses to repeated intraperitoneal hypertonic saline injection. Brain Res. 1993;630:262–270. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90665-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo JW, Duman RS. IL-1beta is an essential mediator of the antineurogenic and anhedonic effects of stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:751–756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708092105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamounier-Zepter V, Ehrhart-Bornstein M, Bornstein SR. Metabolic syndrome and the endocrine stress system. Horm Metab Res. 2006;38:437–441. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-947837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutfy K, Aimiuwu O, Mangubat M, Shin CS, Nerio N, Gomez R, Liu Y, Friedman TC. Nicotine stimulates secretion of corticosterone via both CRH and AVP receptors. J Neurochem. 2012;120:1108–1116. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier SF, Watkins LR. Intracerebroventricular interleukin-1 receptor antagonist blocks the enhancement of fear conditioning and interference with escape produced by inescapable shock. Brain Res. 1995;695:279–282. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00930-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino S, Smith MA, Gold PW. Increased expression of corticotropin-releasing hormone and vasopressin messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus during repeated stress: association with reduction in glucocorticoid receptor mRNA levels. Endocrinology. 1995;136:3299–3309. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.8.7628364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks W, Fournier NM, Kalynchuk LE. Repeated exposure to corticosterone increases depression-like behavior in two different versions of the forced swim test without altering nonspecific locomotor activity or muscle strength. Physiol Behav. 2009;98:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews EH, Liebenberg L. A practical quantification of blood glucose production due to high-level chronic stress. Stress Health. 2012;28:327–332. doi: 10.1002/smi.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell RA, Plummer AJ, Osborne MW. Studies with the ganglionic blocking agent, chlorisondamine chloride in unanesthetized and anesthetized dogs. Circ Res. 1956;4:276–281. doi: 10.1161/01.res.4.3.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty R, Horwatt K, Konarska M. Chronic stress and sympathetic-adrenal medullary responsiveness. Soc Sci Med. 1988;26:333–341. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90398-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire J, Herman JP, Horn PS, Sallee FR, Sah R. Enhanced fear recall and emotional arousal in rats recovering from chronic variable stress. Physiol Behav. 2010;101:474–482. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen KT, Deak T, Owens SM, Kohno T, Fleshner M, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Exposure to acute stress induces brain interleukin-1beta protein in the rat. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2239–2246. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-06-02239.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor KA, Johnson JD, Hammack SE, Brooks LM, Spencer RL, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Inescapable shock induces resistance to the effects of dexamethasone. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28:481–500. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porterfield VM, Gabella KM, Simmons MA, Johnson JD. Repeated stressor exposure regionally enhances beta-adrenergic receptor-mediated brain IL-1beta production. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:1249–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porterfield VM, Zimomra ZR, Caldwell EA, Camp RM, Gabella KM, Johnson JD. Rat strain differences in restraint stress-induced brain cytokines. Neuroscience. 2011;188:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh CR, Nguyen KT, Gonyea JL, Fleshner M, Wakins LR, Maier SF, Rudy JW. Role of interleukin-1 beta in impairment of contextual fear conditioning caused by social isolation. Behav Brain Res. 1999;106:109–118. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remus JL, Stewart LT, Camp RM, Novak CM, Johnson JD. Interaction of metabolic stress with chronic mild stress in altering brain cytokines and sucrose preference. Behav Neurosci. 2015;129:321–330. doi: 10.1037/bne0000056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabban EL, Serova LI. Influence of prior experience with homotypic or heterotypic stressor on stress reactivity in catecholaminergic systems. Stress. 2007;10:137–143. doi: 10.1080/10253890701404078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM, Romero LM, Munck AU. How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:55–89. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.1.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom SC, Miller GE. Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:601–630. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruill TM. Chronic psychosocial stress and hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2010;12:10–16. doi: 10.1007/s11906-009-0084-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterlemann V, Ganea K, Liebl C, Harbich D, Alam S, Holsboer F, Muller MB, Schmidt MV. Long-term behavioral and neuroendocrine alterations following chronic social stress in mice: implications for stress-related disorders. Horm Behav. 2008;53:386–394. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tafet GE, Bernardini R. Psychoneuroendocrinological links between chronic stress and depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:893–903. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5846(03)00162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida S, Nishida A, Hara K, Kamemoto T, Suetsugi M, Fujimoto M, Watanuki T, Wakabayashi Y, Otsuki K, McEwen BS, Watanabe Y. Characterization of the vulnerability to repeated stress in Fischer 344 rats: possible involvement of microRNA-mediated down-regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:2250–2261. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uetsuki N, Segawa H, Mayahara T, Fukuda K. The role of CRF1 receptors for sympathetic nervous response to laparotomy in anesthetized rats. Brain Res. 2005;1044:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich-Lai YM, Arnhold MM, Engeland WC. Adrenal splanchnic innervation contributes to the diurnal rhythm of plasma corticosterone in rats by modulating adrenal sensitivity to ACTH. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R1128–1135. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00042.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich-Lai YM, Engeland WC. Adrenal splanchnic innervation modulates adrenal cortical responses to dehydration stress in rats. Neuroendocrinology. 2002;76:79–92. doi: 10.1159/000064426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Praag HM. Can stress cause depression? World J Biol Psychiatry. 2005;6(Suppl 2):5–22. doi: 10.1080/15622970510030018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg MS, Bhatt AP, Girotti M, Masini CV, Day HE, Campeau S, Spencer RL. Repeated ferret odor exposure induces different temporal patterns of same-stressor habituation and novel-stressor sensitization in both hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity and forebrain c-fos expression in the rat. Endocrinology. 2009;150:749–761. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler DR, Cullinan WE, Herman JP. Organization and regulation of paraventricular nucleus glutamate signaling systems: N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. J Comp Neurol. 2005;484:43–56. doi: 10.1002/cne.20445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.