Abstract

AIM

To investigate a comprehensive range of factors that contribute to long-term patient satisfaction post-total joint replacement (TJR) in people who had undergone knee or hip replacement for osteoarthritis.

METHODS

Participants (n = 1151) were recruited from Nottinghamshire post-total hip or knee replacement. Questionnaire assessment included medication use, the pain-DETECT questionnaire (PDQ) to assess neuropathic pain-like symptoms (NP) and TJR satisfaction measured on average 4.8 years post-TJR. Individual factors were tested for an association with post-TJR satisfaction, before incorporating all factors into a full model. Data reduction was carried out using LASSO and receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to quantify the contribution of variables to post-TJR satisfaction.

RESULTS

After data reduction, the best fitting model for post-TJR satisfaction included various measures of pain, history of revision surgery, smoking, pre-surgical X-ray severity, WOMAC function scores and various comorbidities. ROC analysis of this model gave AUC = 0.83 (95%CI: 0.80-0.85). PDQ scores were found to capture much of the variation in post-TJR satisfaction outcomes: AUC = 0.79 (0.75-0.82). Pre-surgical radiographic severity was associated with higher post-TJR satisfaction: ORsatisfied = 2.06 (95%CI: 1.15-3.69), P = 0.015.

CONCLUSION

These results highlight the importance of pre-surgical radiographic severity, post-TJR function, analgesic medication use and NP in terms of post-TJR satisfaction. The PDQ appears to be a useful tool in capturing factors that contribute to post-TJR satisfaction.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Patient satisfaction, Total joint arthroplasty, Neuropathic pain, Surgery outcomes

Core tip: The growing number of total joint replacement (TJR) surgeries performed worldwide every year means that research in this area has the potential to impact millions of people. These results highlight the importance of a number of factors with regards to post-TJR satisfaction. The pain-DETECT questionnaire for neuropathic pain-like symptoms (NP) appears to be a useful tool in capturing factors that contribute to post-TJR satisfaction. Individuals with NP pre- or post-TJR could be indicated using this short questionnaire and referred for further testing and treatment to improve outcomes at every stage of their osteoarthritis treatment process.

INTRODUCTION

A total joint replacement (TJR) is the only treatment for clinically severe osteoarthritis (OA). A TJR should be considered in individuals with marked symptoms of OA which significantly limit activity and participation and reduce quality of life if conservative treatments (e.g., exercise, weight loss if overweight, analgesic medication) are insufficient[1]. In the United Kingdom alone 160000 TJR are performed every year[2]. Generally very good outcomes are reported post-TJR[3] but pain can remain a concern for some individuals. According to one study, 27% of people who had undergone total hip replacement (THR) and 44% of people who had undergone a total knee replacement (TKR) had joint pain 3-4 years after surgery[4]. This pain can be inflammatory, nociceptive or neuropathic in nature[5].

Patient satisfaction post-TJR has been the subject of some studies[6-10] which have focused only on pain and function post-TJR[11]. Pre-operative radiographic severity, co-occurrence of painful conditions, a history of revision surgery, other comorbidities, and pain catastrophizing have also been linked to post-TJR outcomes in the literature but not all in the same cohort[7,12-15].

Neuropathic pain-like symptoms (NP) are caused by changes or damage to the nervous system, which can result from chronic nociceptive input (as seen in chronic pain states) and nerve damage during surgery[5,16,17]. NP has been reported in people with OA and post-TJR[4,18]. However, to our knowledge, currently no studies have investigated the role of NP on patient satisfaction post-TJR.

As TJR is currently the only long-term treatment for OA, if its effectiveness can be improved with better understanding of the individual differences in post-operative outcomes, this must be addressed. Due to the high number of TJR carried out in the United Kingdom and worldwide, research in this area has the potential to impact many individuals.

The aim of the present study was to investigate a comprehensive range of factors that contribute to long-term patient satisfaction post-TJR in people who had undergone knee or hip replacement for OA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

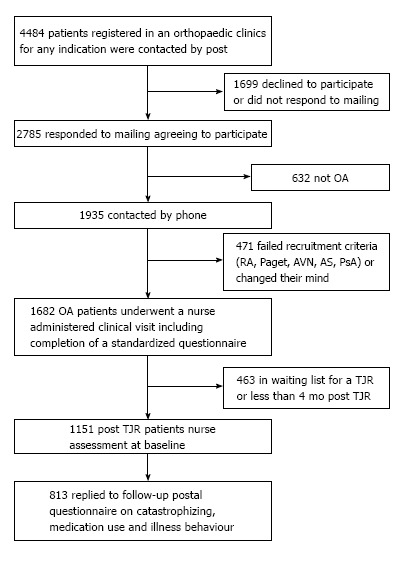

The North Nottinghamshire Research Ethics Committee approved the study protocol (REC number: 07/Q2501/ 22). Participants who had undergone a TJR for OA were recruited from secondary care in Nottinghamshire (n = 1151) and gave written, informed consent. All participants had symptomatic and radiographic OA prior to TJR surgery. Between 2008 and 2011, nurse-administered questionnaires were completed by participants (n = 1219) on average 18 mo after surgery. These questionnaires included information on demographic variables, pain scores, TJR satisfaction and medication use. A subsequent follow-up postal questionnaire was sent to those who consented to further involvement in the study. This questionnaire was very similar in design to the baseline questionnaire. There was an average of 3.3 years between the first and second questionnaires. When the baseline and follow-up responses of participants who completed both questionnaires were compared there were no significant differences in age (P < 0.38), sex (P < 0.89), BMI (P < 0.07) or WOMAC pain scores (P < 0.51). There was not a significant difference in satisfaction levels (P = 0.22). Individuals had not been not phenotyped for pain pre-surgery but pre-operative radiographic severity grade has been linked previously to TJR outcomes[12]. The study design is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow-chart of participant recruitment for the current study.

Statistical analysis

Statistical review of this study was performed by a biomedical statistician. The statistics package R (version 3.0.2) was used to run logistic regression analyses to measure associations between TJR satisfaction and potential risk factors.

To select the risk factors contributing to post-TJR satisfaction, the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator method (LASSO) was used. LASSO is a feature selection method which, given a set of input measurements and an outcome measurement (in this case post-TJR satisfaction), fits a linear model[19]. We employed a LASSO-regularised regression model as implemented by the R package “glmnet”[20] (http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/glmnet/index.html) using a logistic link function and the fitted LASSO coefficients derived were used.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to quantify the contribution of variables in the above models. The discrimination ability of the models was examined using the “PredictABEL” package for R (http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/PredictABEL/index.html).

Trait definitions for statistical analysis

Neuropathic pain-like symptoms at the operated joints (knees or hips): The PDQ is a validated instrument for assessing NP. Scores range from 0-35, with > 12 indicating possible NP and ≥ 19 indicating likely NP[21].

Pain severity: A visual analogue scale (VAS) was used to categorise individuals with high or low pain intensity at the operated joint (knee or hip). Scores range from 0-10, with ≥ 6 used to categorise high pain intensity.

TJR satisfaction: Individuals were asked to state how satisfied they felt with their TJR using an ordinal scale of “very satisfied”, “not very satisfied” and “dissatisfied”. For logistic regression analysis, individuals were dichotomised between: (1) “very satisfied”; and (2) “not very satisfied” and “dissatisfied”.

Radiographic severity: The extent of joint damage evident by X-rays was categorised by assessment of pre-surgery knee and hip radiographs by a single observer. For knees, the Kellgren-Lawrence (K/L) grading system was used. Scores range from 0-4, with ≥ 3 classified as severe and 2 classified as not severe (K/L < 2 no OA)[22]. An association with minimum joint space width (JSW) pre-surgery and pain post-surgery has been reported in a separate cohort[12]. The minimum JSW was therefore used to classify hip OA, with minimum JSW ≤ 2.5 mm (which is a standard cut-off)[23] being classified as radiographically severe. For bilateral surgery the joint with the most severe radiographic score was used.

Pain catastrophizing: The 13-item Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) is a measure of the tendency to exaggerate the threat of a perceived harmful stimulus[24]. Scores range from 0-52 and the highest tertile was used as a cut-off point to classify individuals as high catastrophizers, as previously described[25].

WOMAC pain, stiffness and function: The OA-specific Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) questionnaire includes questions about pain (scored from 0-20), stiffness (scored from 0-8) and function (scored from 0-76)[26]. WOMAC function scores were categorised according to an OMERACT-defined PASS score of “acceptable function” (a score of ≤ 22) to allow a clinical guideline to be used in this study to put the importance of post-TJR satisfaction into a clinical context[27,28].

Medication use

Questionnaire responses were used to classify participants as taking over-the-counter analgesics (OTC), opioids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or other prescription medications which can be used to treat pain, as previously described[25].

Comorbidities

Comorbid conditions are commonly seen in people with OA, and people with OA are more likely to develop comorbid conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes[29]. A list of comorbidities was included in the questionnaire. Participants were asked to indicate which of these conditions they had been previously diagnosed with by a doctor.

RESULTS

The descriptive characteristics, stratified by TJR satisfaction status, are shown in Table 1. One fourth of study participants (290) were dissatisfied or not very satisfied with the outcome of their surgery. The study was thus powered (80%, P < 0.05) to detect associations with odds ratios of 1.75 or higher for binary traits with a prevalence of 10% or higher in the satisfied group, such as neuropathic pain (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics categorised by total joint replacement satisfaction status and their contribution to the risk of dissatisfaction post-total joint replacement

| Trait | Very satisfied (n = 861) | Not very satisfied (n = 227) | Dissatisfied (n = 63) | OR not very satisfied/dissatisfied (95%CI)1 | |

| Demographic and morphometric | Age ± SD (yr) | 73.2 ± 8.6 | 73.0 ± 8.8 | 72.2 ± 9.1 | 1.00 (0.98-1.01) |

| % female | 57.4 | 56.8 | 47.6 | 0.85 (0.65-1.12) | |

| BMI ± SD (kg/m2) | 29 ± 5.2 | 29.4 ± 5.1 | 30.7 ± 5.9 | 1.03 (1.00-1.06)a | |

| Type of surgery | THR (n = 494) | 407 (82.4%) | 74 (15.0%) | 13 (2.6%) | 0.58 (0.44-0.77)e |

| TKR (n = 591) | 410 (69.4%) | 136 (23.0%) | 45 (7.6%) | 2.02 (1.50-2.71)e | |

| THR + TKR (n = 66) | 44 (66.7%) | 17 (25.8%) | 5 (7.6%) | 1.63 (0.95-2.78) | |

| Years since most recent surgery | 4.26 | 3.96 | 4.58 | 0.99 (0.96-1.03) | |

| Pre-operative X-ray | Radiographically severe OA | 92.10% | 93.40% | 96.50% | 0.49 (0.27-0.87)a |

| History of surgery | Previous arthroscopic knee surgery3 | 20.00% | 26.40% | 34.90% | 1.65 (1.21-2.25)c |

| Revision surgery | 5.70% | 9.30% | 14.30% | 2.36 (1.44-3.86)e | |

| Psychological | % depression | 15.9 | 22.0 | 28.6 | 1.64 (1.17-2.30)c |

| PCS score (0-52) | 8.2 | 12.8 | 19.7 | 1.06 (1.05-1.08)e | |

| Top tertile of PCS2 | 20.80% | 37.00% | 55.60% | 3.40 (2.52-4.59)e | |

| Use of medication | % opioid | 21.7 | 39.5 | 41.3 | 2.37 (1.77-3.18)e |

| % OTC | 49.0 | 64.5 | 61.9 | 1.33 (0.84-2.12) | |

| % NSAIDs | 7.8 | 12.3 | 3.2 | 1.83 (1.38-2.42)e | |

| % other prescription analgesics | 12.2 | 20.0 | 23.8 | 1.85 (1.29-2.66)e | |

| Measures of pain | PDQ score (0-35) | 4.8 | 10.1 | 14.3 | 1.15 (1.13-1.18)e |

| Possible Neuropathic Pain (PDQ > 12) | 10.00% | 33.90% | 57.10% | 5.91 (4.22-8.29)e | |

| Likely Neuropathic Pain (PDQ ≥ 19) | 6.50% | 18.10% | 34.90% | 7.66 (4.80-12.22)e | |

| VAS (0-10) | 3.1 | 5.8 | 7.0 | 1.35 (1.29-1.41)e | |

| HighVAS (> 5) | 30.80% | 61.20% | 76.20% | 6.47 (4.80-8.73)e | |

| WOMAC pain (0-20) | 5.2 | 8.5 | 10.9 | 1.28 (1.23-1.33)e | |

| WOMAC stiffness (0-8) | 2.9 | 4.1 | 4.4 | 1.62 (1.49-1.76)e | |

| WOMAC function (0-76) | 25.7 | 38.0 | 47.8 | 1.07 (1.06-1.08)e | |

| Comorbidities | % heart disease/angina | 16.7 | 19.4 | 27.0 | 1.34 (0.95-1.89) |

| % stroke | 5.1 | 9.3 | 12.7 | 2.09 (1.26-3.44)c | |

| % hypertension | 52.3 | 50.2 | 57.1 | 0.95 (0.72-1.25) | |

| % asthma/COPD | 13.8 | 15.4 | 14.3 | 1.07 (0.73-1.57) | |

| % irritable bowel syndrome | 10.2 | 14.5 | 11.1 | 1.44 (0.96-2.17) | |

| % diabetes | 11.8 | 15.0 | 19.0 | 1.28 (0.86-1.90) | |

| % gout | 7.5 | 11.9 | 11.1 | 1.50 (0.95-2.37) | |

| % osteoporosis | 11.0 | 10.1 | 19.0 | 1.23 (0.80-1.88) | |

| % cancer | 15.9 | 19.8 | 17.5 | 1.29 (0.91-1.83) | |

| % current smoker | 6.5 | 11.0 | 14.3 | 1.93 (1.22-3.07)c |

All ORs are adjusted for age, sex and BMI;

Individuals in the top tertile of scores for the PCS questionnaire were classified as high catastrophizing;

This classification includes any previous arthroscopic knee surgery.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001. PCS: Pain Catastrophizing Scale; BMI: Body mass index.

On univariate analysis, the majority of the variables tested were found to be significantly associated with satisfaction post-TJR. This includes a higher BMI, various measures of pain (such as PDQ scores, high pain intensity and WOMAC pain scores), WOMAC function scores and pain catastrophizing (Table 1). Additionally, THR participants reported higher levels of being very satisfied (82.4%) than TKR patients (69.4%) (Table 1). Some factors were highly correlated with each other, such as PDQ scores and high pain intensity, PDQ scores and WOMAC pain scores and WOMAC pain scores and high pain intensity (P < 0.001 for all).

Given the large number of factors associated, many of them correlated with each other, we performed data reduction, using LASSO to identify which factors remain important contributors to post-TJR, post-THR and post-TKR satisfaction. After data reduction, the factors that remained in all three groups were: BMI, WOMAC function scores, PDQ scores, high pain intensity, severe pre-surgery radiographic OA and a past stroke. The full results of these analyses are shown in Table 2. Some differences were observed in the factors that contribute to satisfaction post-THR and post-TKR, most notably a history of a revision surgery for THR and the WOMAC stiffness score for TKR. In both cases PDQ and VAS scores contribute significantly after adjustment for all other factors.

Table 2.

The best fitting and pain-DETECT questionnaire models showing the contribution of factors to post-total joint replacement, post-total hip replacement and post-total knee replacement satisfaction

| Full/best fitting model | pain-DETECT questionnaire scores | |

| Total joint replacement satisfaction | 2.207 + (-0.013∙PCS) + (0.189∙sex) + (-0.398∙TKR) + (0.016∙BMI) + (-0.027∙WOMAC function) + (-0.042∙WOMAC stiffness) + (-0.012∙past knee surgery) + (-0.056∙PDQ) + (-0.483∙highVAS) + (-0.380∙revision surgery) + (0.352∙severe pre-surgical radiographic OA) + (-0.066∙OTC) + (-0.113∙opioid) + (-0.010∙current smoker) + (-0.218∙stroke) + (0.051∙hypertension) + (0.062∙IBS) + (-0.055∙gout) + (-0.123∙depression) | 2.796 + (-0.142∙PDQ) + (-0.015∙age) + (0.382∙sex) + (0.004∙BMI) |

| Total hip replacement satisfaction | 2.985 + (0.014∙years since surgery) + (-0.018∙age) + (0.036∙BMI) + (-0.036∙WOMAC function) + (0.599∙past knee surgery) + (-0.018∙PDQ) + (-0.725∙high VAS) + (-0.723∙revision surgery) + (0.779∙severe pre-surgical radiographic OA) + (-0.248∙OTC) + (-0.119∙opioid) + (-0.429∙other medications for pain relief) + (-0.442∙current smoker) + (-0.014∙stroke) + (-0.514∙depression) + (-0.022∙cancer) | 4.788 + (-0.121∙PDQ) + (-0.038∙age) + (0.036∙sex) + (0.008∙BMI) |

| Total knee replacement satisfaction | 2.425 + (-0.018∙PCS) + (0.190∙sex) + (0.00045∙BMI) + (-0.015∙WOMAC function) + (-0.130∙WOMAC stiffness) + (-0.076∙PDQ) + (-0.313∙high VAS) + (0.009∙severe pre-surgical radiographic OA) + (-0.143∙stroke) + (0.072∙hypertension) + (0.334∙IBS) + (-0.120∙gout) | 1.072 + (-0.146∙PDQ) + (0.003∙age) + (0.467∙sex) + (0.011∙BMI) |

Higher pre-operative radiographic severity was also significantly associated with increased odds of TJR satisfaction: ORsatisfied = 2.06 (1.15-3.69), P = 0.015.

It was investigated whether patient satisfaction was related to measures of healthcare usage, specifically the use of analgesic medication. Strong associations were found between dissatisfaction and an increased likelihood of the use of some prescription analgesics (opioids and other prescription medications which can be used to treat pain) and OTC analgesics, but not prescription NSAIDs (Table 1). After adjustment for possible NP, high pain catastrophizing and high pain intensity (VAS) these associations become non-significant except in the case of opioids and OTC analgesics [ORdissatisfied = 1.68 (1.21-2.34), P = 0.002; ORdissatisfied = 1.44 (1.06-1.97), P = 0.020, respectively].

Post-TJR satisfaction is strongly associated with a measure of acceptable function post-TJR, according to OMERACT-defined PASS scores in the literature[27,28]. This definition of acceptable function, according to a clinical guideline, was a very strong contributor to post-TJR satisfaction in this study after adjusting for age, sex and BMI: ORsatisfied = 9.88 (95%CI: 6.58-14.85), P < 0.001. This association remained significant after further adjustment for possible NP, high pain catastrophizing and high pain intensity: ORsatisfied = 4.82 (95%CI: 3.08-7.55), P < 0.001.

With regards to comorbidities, a history of stroke was associated with an increased risk of dissatisfaction post-TJR, as was being a current smoker (vs ex- smokers and people who have never smoked); P < 0.01 for both, see Table 1.

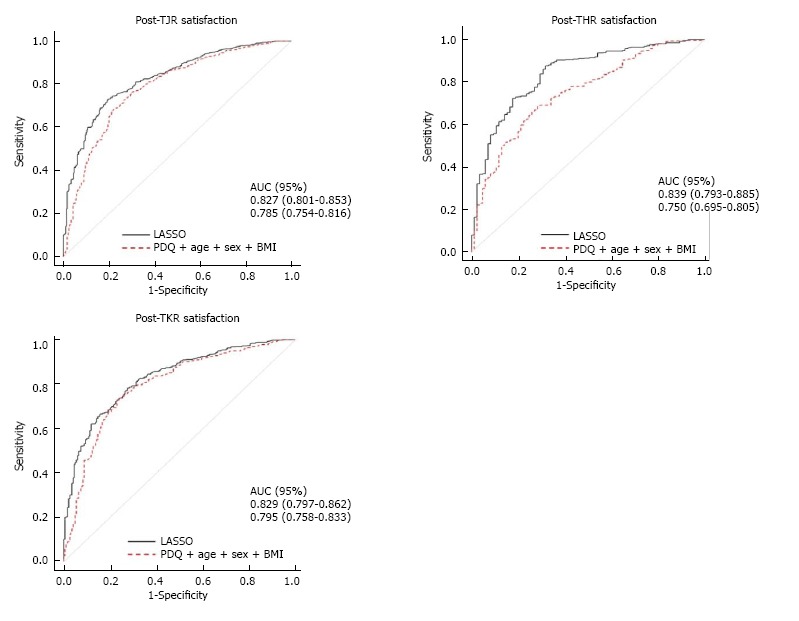

It was quantified how much these models contribute to satisfaction. The results of ROC analysis of the best-fitting model for each surgery group are shown in Table 2 and Figure 2. The results show that the list of identified factors explains an AUC of 0.83 of patient satisfaction for post-TJR, 0.84 for post-THR and 0.83 for post-TKR. This, however, includes a large number of factors and it was investigated whether one of the factors may capture the effects of most of the other factors.

Figure 2.

Receiver operator characteristic curves adjusted for age, sex and body mass index to show the amount of post-surgery satisfaction predicted by preoperative radiographic severity, pain-DETECT questionnaire scores and the best fit model. A: Post-TJR (THR and TKR combined); B: Post-TKR; C: Post-THR. TJR: Total joint replacement; THR: Total hip replacement; TKR: Total knee replacement.

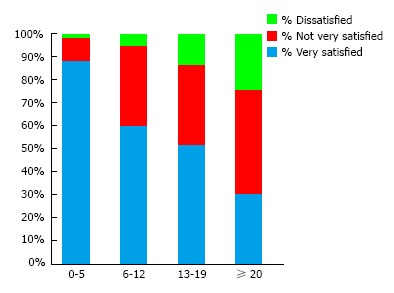

Possible NP, classified using PDQ scores, was seen in 17.3% of participants in this study. However, in the dissatisfied group the prevalence of possible NP was 3.8 times higher than in the very satisfied group ORpossNP = 5.91 (4.22-8.29), P < 0.001 and the prevalence of likely NP was 5.4 times higher: ORlikNP = 7.66 (4.80-12.22), P < 0.001 (see Table 1). Possible NP was less common in THR than TKR participants (11.9% and 22.3%, respectively) (Table 1). Likely NP has been reported previously to be present only in a small proportion of individuals post-TJR[4] using as a definition a PDQ > 19. However strong differences exist in satisfaction at various lower cut-offs which explains why pain-DETECT scores capture such a large proportion of patient satisfaction in these data (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Proportion of post-total joint replacement patients reporting to be dissatisfied, not very satisfied or very satisfied depending on their pain-DETECT score.

Given this strong effect we hypothesised that PDQ scores, being strongly correlated with pre-surgery X-ray scores (Spearman’s rho = -0.13, P < 0.001) and associated with post-TJR pain intensity [ORhighpainintensity = 1.35 (1.30-1.40), P < 0.001], may capture much of the variation in post-TJR satisfaction outcomes, and indeed we find that this is the case. According to ROC analysis of PDQ scores (adjusted for age, sex and BMI), there is a significant contribution to post-TJR, post-THR and post-TKR satisfaction when this model is used (Table 2 and Figure 2). AUC values of 0.75 and over were reached in all three groups, even without the inclusion of any of the other available measures.

DISCUSSION

This study incorporated a comprehensive range of factors and shows that a number of factors including pain, comorbidities, smoking, history of revision surgery and pre-surgical radiographic severity contribute to post-TJR satisfaction 4.8 years after surgery. Scores measuring the presence of NP appear to capture a large proportion of the variation seen.

Patient satisfaction is an outcome measure which is simple to use and accounts for the complex aspects of TJR[30]. It has been recommended that patient satisfaction should be incorporated into assessments of post-TJR outcomes[30]. Our results suggest that although post-TJR satisfaction is influenced by a large number of factors, it is well summarised by one single instrument, namely PDQ scores.

The proportion of possible NP identified in this study falls within the range reported by previous studies on NP post-TJR (reviewed in[31]) particularly when differences in methodology and sample composition are taken into consideration[4,15,32-37]. At first sight the importance of NP post-TJR detailed here appears to contrast with the report by Wylde et al[4] who suggested that NP is a minor component of post-TJR pain.

The current data indicate that people who undergo TJR with only modest radiographic structural damage are more likely to report NP post-surgery. Although this might suggest that the NP was also present pre-surgery, we lack the pre-operative pain assessments necessary to confirm if that is the case. In addition, pain may derive from other sources, such as bone marrow lesions, that are not evident on radiographs and may still be present post-surgery[38]. Central nervous system involvement in OA, such as seen in NP, seems likely when the inconsistent correlation between pain and radiographic severity and the non-linear relationship between nociception and pain experienced are considered[17] supporting the findings in this study.

In this study we fitted prediction models for patient dissatisfaction using all the contributing risk factors selected by LASSO. These models are fairly complicated in terms of the number of variables and therefore may not be applicable in clinical practice. However, we also show that PDQ scores have almost as much predictive value as the best fitting models. Therefore, in terms of clinical application our data suggest that assessing NP symptoms using the PDQ will help identify patients at highest risk of surgery dissatisfaction.

One key limitation to this study is the lack of pre-surgical pain data. However, Phillips et al[39] found that it was not possible to reliably predict post-TKR outcomes from pre-operative pain intensity and PDQ scores[39], whereas Dualé et al[16] have reported a higher risk of NP post-surgery if peripheral NP is present pre-surgery. Although the self-administered PDQ allows data collection from a large number of individuals it does not provide definitive evidence of NP[40]. Nonetheless, one study showed a correlation between PDQ scores and periaqueductal grey matter activation (which is involved in central sensitisation) in people with OA in areas of referred pain in response to punctate stimuli[41].

Although in this study we did not use the widely accepted National Joint Registry agreed Patient Reported Outcomes (PROMS) data[42], 92% of the questions in the Oxford hip and knee score (OXHS and OXKS, respectively) questionnaires are accounted for by the questionnaire used in this study, as was 83% of the content in the EQ-5D questionnaire. The questionnaire measured used in this study therefore reflects a large majority of the material covered in the PROMS. On the other hand we have examined other factors that are not usually included as part of post TJR PROMS, such as comorbidities, use of analgesic medication and pre-surgery X-ray severity all of which contribute to patient self-reported satisfaction in our data. To our knowledge this is one of the few studies to date which has looked at pain assessment integrated with comorbidities and use of medication.

Some of the factors identified as contributing to satisfaction could be addressed pre-surgery or considered when assessing outcomes post-surgery. The presence of comorbid conditions appears also to have a considerable effect on patient satisfaction, and this information may be use to manage patient expectations pre-surgery.

In conclusion, the PDQ appears to be particularly useful in capturing factors that contribute to post-TJR outcomes and may be considered as an important post-surgical assessment. These results also highlight the importance of understanding the mechanisms behind NP symptoms post-TJR, as it is a significant factor contributing to post-TJR satisfaction and, importantly, affects a considerable proportion of individuals post-TJR.

COMMENTS

Background

Total joint replacement is a very common type of surgery. Understanding the determinants of patient satisfaction is necessary to address the increasing need for this type of surgery with population aging.

Research frontiers

The authors investigated for the first time the relationship between pre-operative radiographic severity and neuropathic pain symptoms and satisfaction post total joint replacement.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The authors show that neuropathic pain symptoms are the most important contributor to post-total joint replacement satisfaction. Other contributors are smoking and low pre-operative radiographic severity.

Applications

The prediction models used in this work can be applied to patients undergoing total joint replacement surgery for osteoarthritis.

Terminology

Neuropathic pain symptoms, caused by changes or damage to the nervous system. Pre-operative radiographic severity, refers to the extent of large joint (hip or knee) damage detected in X-rays prior to surgery.

Peer-review

This manuscript aims to evaluate factors predict satisfaction post total joint replacement. It is a vary serious paper dealing with the results of joints replacement. A well written paper and well organized study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Sally Doherty and Maggie Wheeler to patient assessments at baseline, data collection and entry.

Footnotes

Supported by PhD studentship awarded by the University of Nottingham (to Warner SC); EULAR project grant to AMV, No. 108239; ARUK Pain Centre, No. 18769.

Institutional review board statement: The North Nottinghamshire Research Ethics Committee approved the study protocol (REC number: 07/Q2501/22).

Informed consent statement: All participants gave written, informed consent prior to study inclusion.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no relevant conflicts of interest.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: December 2, 2016

First decision: February 17, 2017

Article in press: August 16, 2017

P- Reviewer: Fisher DA, Fenichel I, Tangtrakulwanich B S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

Contributor Information

Sophie C Warner, Academic Rheumatology, University of Nottingham, Clinical Sciences Building, Nottingham City Hospital, Nottingham NG5 1PB, United Kingdom; Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, University of Leicester and National Institute for Health Research, Leicester Cardiovascular Biomedical Research Unit, Leicester LE3 9QP, United Kingdom. scw27@le.ac.uk.

Helen Richardson, Academic Rheumatology, University of Nottingham, Clinical Sciences Building, Nottingham City Hospital, Nottingham NG5 1PB, United Kingdom.

Wendy Jenkins, Academic Rheumatology, University of Nottingham, Clinical Sciences Building, Nottingham City Hospital, Nottingham NG5 1PB, United Kingdom.

Thomas Kurien, Arthritis Research UK Pain Centre, Nottingham NG5 1PB, United Kingdom; Academic Division of Trauma and Orthopaedics, Queens Medical Centre, Nottingham NG7 2UH, United Kingdom.

Michael Doherty, Academic Rheumatology, University of Nottingham, Clinical Sciences Building, Nottingham City Hospital, Nottingham NG5 1PB, United Kingdom; Arthritis Research UK Pain Centre, Nottingham NG5 1PB, United Kingdom.

Ana M Valdes, Academic Rheumatology, University of Nottingham, Clinical Sciences Building, Nottingham City Hospital, Nottingham NG5 1PB, United Kingdom; Arthritis Research UK Pain Centre, Nottingham NG5 1PB, United Kingdom.

References

- 1.National Institure for Health and Care Excellence. NICE Pathways: Management of osteoarthritis. [accessed 2016 May 1] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Joint Registry for England and Wales. Hemel Hempstead: National Joint Registry for England and Wales; 2010. [accessed 2016 Jun 20]; 2016. 7th Annual Report. Available from: http://www.njrcentre.org.uk/njrcentre/Portals/0/NJR%207th%20Annual%20Report%202010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Losina E, Walensky RP, Kessler CL, Emrani PS, Reichmann WM, Wright EA, Holt HL, Solomon DH, Yelin E, Paltiel AD, et al. Cost-effectiveness of total knee arthroplasty in the United States: patient risk and hospital volume. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1113–1121; discussion 1121-1122. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wylde V, Hewlett S, Learmonth ID, Dieppe P. Persistent pain after joint replacement: prevalence, sensory qualities, and postoperative determinants. Pain. 2011;152:566–572. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet. 2006;367:1618–1625. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68700-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunbar MJ, Haddad FS. Patient satisfaction after total knee replacement: new inroads. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B:1285–1286. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B10.34981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunbar MJ, Richardson G, Robertsson O. I can’t get no satisfaction after my total knee replacement: rhymes and reasons. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B:148–152. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B11.32767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robertsson O, Dunbar M, Pehrsson T, Knutson K, Lidgren L. Patient satisfaction after knee arthroplasty: a report on 27,372 knees operated on between 1981 and 1995 in Sweden. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71:262–267. doi: 10.1080/000164700317411852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross CK, Steward CA, Sinacore JM. A comparative study of seven measures of patient satisfaction. Med Care. 1995;33:392–406. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199504000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carr AJ, Robertsson O, Graves S, Price AJ, Arden NK, Judge A, Beard DJ. Knee replacement. Lancet. 2012;379:1331–1340. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60752-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clement N. Patient factors that influence the outcome of total knee replacement: a critical review of the literature. OA Orthopaedics. 2013;1:11. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valdes AM, Doherty SA, Zhang W, Muir KR, Maciewicz RA, Doherty M. Inverse relationship between preoperative radiographic severity and postoperative pain in patients with osteoarthritis who have undergone total joint arthroplasty. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41:568–575. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peter WF, Dekker J, Nelissen RG, Fiocco M, van der Linden-van der Zwaag HM, Vermeulen EM, Tilbury C, Vliet Vlieland TP. Comorbidity in osteoarthritis patients following hip and knee joint replacement surgery. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2014;22:S185–S6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards RR, Haythornthwaite JA, Smith MT, Klick B, Katz JN. Catastrophizing and depressive symptoms as prospective predictors of outcomes following total knee replacement. Pain Res Manag. 2009;14:307–311. doi: 10.1155/2009/273783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nikolajsen L, Brandsborg B, Lucht U, Jensen TS, Kehlet H. Chronic pain following total hip arthroplasty: a nationwide questionnaire study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50:495–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.00976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dualé C, Ouchchane L, Schoeffler P; EDONIS Investigating Group, Dubray C. Neuropathic aspects of persistent postsurgical pain: a French multicenter survey with a 6-month prospective follow-up. J Pain. 2014;15:24.e1–24.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graven-Nielsen T, Wodehouse T, Langford RM, Arendt-Nielsen L, Kidd BL. Normalization of widespread hyperesthesia and facilitated spatial summation of deep-tissue pain in knee osteoarthritis patients after knee replacement. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2907–2916. doi: 10.1002/art.34466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hochman JR, Gagliese L, Davis AM, Hawker GA. Neuropathic pain symptoms in a community knee OA cohort. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19:647–654. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso: a retrospective. J R Stat Soc: Series B (Stat Methodol) 2011;73:273–282. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Regularization Paths for Generalized Linear Models via Coordinate Descent. J Stat Softw. 2010;33:1–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, Tölle TR. painDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:1911–1920. doi: 10.1185/030079906X132488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16:494–502. doi: 10.1136/ard.16.4.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Croft P, Cooper C, Wickham C, Coggon D. Defining osteoarthritis of the hip for epidemiologic studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:514–522. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and validation. Physchol Assessment. 1995;7:524–532. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valdes AM, Warner SC, Harvey HL, Fernandes GS, Doherty S, Jenkins W, Wheeler M, Doherty M. Use of prescription analgesic medication and pain catastrophizing after total joint replacement surgery. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;45:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Escobar A, Gonzalez M, Quintana JM, Vrotsou K, Bilbao A, Herrera-Espiñeira C, Garcia-Perez L, Aizpuru F, Sarasqueta C. Patient acceptable symptom state and OMERACT-OARSI set of responder criteria in joint replacement. Identification of cut-off values. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maxwell JL, Felson DT, Niu J, Wise B, Nevitt MC, Singh JA, Frey-Law L, Neogi T. Does clinically important change in function after knee replacement guarantee good absolute function? The multicenter osteoarthritis study. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:60–64. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stang PE, Brandenburg NA, Lane MC, Merikangas KR, Von Korff MR, Kessler RC. Mental and physical comorbid conditions and days in role among persons with arthritis. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:152–158. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000195821.25811.b4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halawi MJ. Outcome Measures in Total Joint Arthroplasty: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Directions. Orthopedics. 2015;38:e685–e689. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20150804-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haroutiunian S, Nikolajsen L, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS. The neuropathic component in persistent postsurgical pain: a systematic literature review. Pain. 2013;154:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baker PN, van der Meulen JH, Lewsey J, Gregg PJ; National Joint Registry for England and Wales. The role of pain and function in determining patient satisfaction after total knee replacement. Data from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:893–900. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B7.19091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clarke H, Kay J, Mitsakakis N, Katz J. Acute pain after total hip arthroplasty does not predict the development of chronic postsurgical pain 6 months later. J Anesth. 2010;24:537–543. doi: 10.1007/s00540-010-0960-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinez V, Fletcher D, Bouhassira D, Sessler DI, Chauvin M. The evolution of primary hyperalgesia in orthopedic surgery: quantitative sensory testing and clinical evaluation before and after total knee arthroplasty. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:815–821. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000278091.29062.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Remérand F, Le Tendre C, Baud A, Couvret C, Pourrat X, Favard L, Laffon M, Fusciardi J. The early and delayed analgesic effects of ketamine after total hip arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized, controlled, double-blind study. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1963–1971. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181bdc8a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanders JC, Gerstein N, Torgeson E, Abram S. Intrathecal baclofen for postoperative analgesia after total knee arthroplasty. J Clin Anesth. 2009;21:486–492. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh JA, Lewallen D. Predictors of pain and use of pain medications following primary Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA): 5,707 THAs at 2-years and 3,289 THAs at 5-years. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurien T, Kerslake R, Haywood B, Pearson RG, Scammell BE. Liverpool, UK: British Orthopaedic Research Society; 2015. Resection and resorption of bone marrow lesions is associated with improvement of pain after knee replacement surgery. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Phillips JR, Hopwood B, Arthur C, Stroud R, Toms AD. The natural history of pain and neuropathic pain after knee replacement: a prospective cohort study of the point prevalence of pain and neuropathic pain to a minimum three-year follow-up. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B:1227–1233. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B9.33756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bouhassira D, Attal N. Diagnosis and assessment of neuropathic pain: the saga of clinical tools. Pain. 2011;152:S74–S83. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gwilym SE, Keltner JR, Warnaby CE, Carr AJ, Chizh B, Chessell I, Tracey I. Psychophysical and functional imaging evidence supporting the presence of central sensitization in a cohort of osteoarthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1226–1234. doi: 10.1002/art.24837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Health and Social Care Information Centre. Monthly Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) in England. [accessed 2016 May 1] Available from: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/proms. [Google Scholar]