Abstract

Objectives

Some studies suggest that bioavailable 25-(OH)D is more accurate than total 25-(OH)D as an assessment of vitamin D status in black individuals, We hypothesized that increases in bioavailable 25-(OH)D would correlate better with improvement in bone outcomes among black HIV-infected adults.

Design

This is a secondary analysis of ACTG A5280, a randomized, double-blind study of Vitamin D3 and calcium (VitD/Ca) supplementation in HIV-infected participants initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Methods

Effect of VitD/Ca on total and calculated bioavailable 25-(OH)D, parathyroid hormone (PTH), bone turnover markers (BTMs) and bone mineral density (BMD) in black and non-black participants were evaluated at 48 weeks. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests and Wilcoxon rank sum tests assessed within and between-race differences.

Results

Of 165 participants enrolled, 129 (40 black and 89 non-black) had complete data. At baseline, black participants had lower total 25-(OH)D [median (Q1,Q3) 22.6 (15.8, 26.9) vs. 31.1 (23.1, 38.8) ng/ml, p<0.001] but higher bioavailable 25-(OH)D [2.9 (1.5, 5.2) vs. 2.0 (1.5, 3.0) ng/ml, p=0.022] than non-black participants. After 48 weeks of VitD/Ca supplementation, bioavailable 25-(OH)D increased more in black than non-black participants, but there were no between-race differences in change in BTMs or BMD. The associations between increases in 25-(OH)D levels and change in bone outcomes appeared similar for both total and bioavailable 25-(OH)D.

Conclusions

Baseline and change in bioavailable 25-(OH)D were higher among black adults initiating ART with VitD/Ca; however, associations between 25-(OH)D and bone outcomes appeared similar for total and bioavailable 25-(OH)D. The assessment of total 25-(OH)D may be sufficient for evaluation of vitamin D status in black HIV-infected individuals.

Keywords: vitamin D, vitamin D binding protein, HIV, bone loss

Introduction

In ACTG A5280, we reported that vitamin D and calcium (VitD/Ca) supplementation prevented bone loss that has been associated with antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation with efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir DF (EFV/FTC/TDF)[1]. After 48 weeks, percentage decline in bone mineral density (BMD) at total hip was smaller in the VitD/Ca arm compared to the placebo arm. Notably, no racial differences were apparent regarding this effect on BMD.

In the general population, black Americans have lower levels of 25-(OH)D than white Americans, yet have higher bone mass and lower fracture rates [2]. Studies from the general population have highlighted racial differences in the relationship between vitamin D and both parathyroid hormone (PTH) and BMD [3], suggesting that the threshold for vitamin D deficiency may differ between black and white individuals [3]. One plausible explanation may be related to differences in expression of Vitamin D binding protein (VDBP). VDBP is the major serum transport protein for all vitamin D metabolites. VDBP has both a high capacity and affinity for vitamin D metabolites, binding 85% to 90% of total circulating 25-(OH)D. Bioavailable 25-(OH)D consists of albumin-bound 25-(OH)D (10–15% of total) and free 25-(OH)D (less than 1% of total)[4]. Recently, Powe et al reported that black Americans have lower serum VDBP concentrations as measured by a monoclonal antibody assay than white Americans; therefore, despite a lower total 25-(OH)D level in black Americans, the calculated bioavailable concentration of 25-(OH)D is similar for black and white Americans [5]. These data suggest that the commonly reported low vitamin D levels for black Americans may reflect the measurement of total rather than bioavailable 25-(OH)D concentrations[6]; however, this interpretation remains controversial since results differ with another VDBP assay[7–10]. In addition, two recent studies reported increases in both PTH and VDBP with initiation of tenofovir (TDF)-containing ART [11, 12], suggestive of an induced “functional” vitamin D defiency, but neither study calculated bioavailable 25-(OH)D or compared differences by race.

In this pre-specified secondary analysis of A5280, we sought to clarify the complex relationship between vitamin D metabolism and race in HIV-infected participants receiving TDF-containg ART, by examing the effect of VitD/Ca supplementation on total 25-(OH)D, bioavailable 25-(OH)D, VDBP, PTH, bone turnover markers levels and BMD by race in black and non-black participants. We hypothesized that changes in bioavailable 25-(OH)D would correlate better with changes in calciotropic hormone levels and bone outcomes in black persons.

Methods

ACTG A5280 was a 48-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in which 165 HIV-infected participants, naïve to ART, with 25-(OH)D level ≥10 and <75 ng/mL (≥25 and <188 nmol/L), CrCl ≥60 ml/min by Cockcroft-Gault, and serum calcium <10.5 mg/dl were randomized to receive 4000 IU cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) daily plus 500mg calcium carbonate twice daily or identically matching placebos (Tishcon Corporation, Westbury, NY). Primary and secondary treatment outcomes of percentage change in total hip and lumbar spine BMD, and bone turnover markers, procollagen-1 N-terminal peptide (P1NP) and C-terminal telopeptide of type 1 collagen (CTX). from baseline to 48 weeks have been previously reported [1].

Biomarker Assays

Serum samples were stored at −80°C until batched analysis at the Irving Institute Biomarkers Core at Columbia University Medical Center (New York, NY). We measured 25(OH) D2 and D3 by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry; intact PTH (radioimmunoassay; Scantibodies, Santee, CA; interassay CV, 6.8%). We used the same monoclonal VDBP antibody assay use by Powe et al [5] (RIA; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; interassay CV, 7.2%).

Statistical analyses

This analysis included all available data regardless of treatment change/discontinuation. Race groups in this report are defined as black and non-black. The black group included all A5280 participants who self-identified as black or African American (N=52). The non-black group included those self-identifying as white, Asian, or American Indian (N=97). Participants with more than one race and with unknown race (N=7) were excluded from the analyses with race. All 25-(OH)D Vitamin D values below the lower limit of 1.25 ng/mL were imputed to 0 ng/mL and VDBP values above the upper limit of 500 ug/mL were imputed to 501 ug/mL. Bioavailable vitamin D was calculated using a formula that includes total 25-(OH)D, VDBP and albumin levels from Powe et al [5]. The primary outcome measures of interest were defined by absolute change from baseline; post-hoc secondary analyses outcomes defined as percentage change from based were also displayed graphically.

Stratified Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to test for differences in outcomes between the two treatment arms, stratified by the screening 25-(OH)D vitamin D stratum (10–20 ng/mL vs. 21–75 ng/mL). Exact Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to test for differences in the two racial groups (black vs. non-black both with respect to baseline characteristics as well as the primary and secondary outcomes of interest). Spearman correlations were used to evaluate associations between outcomes. Non-parametric smooth curves LOESS fits with 95% confidence limits were added to each scatter plot. All analyses by race were performed separately within treatment group. In the setting of relatively small subgroup sample sizes, inferences regarding between race group differences in response to treatment are guided by both the magnitude of effect size as well as statistical significance.

All statistical tests are two-sided interpreted at the 5% nominal level of significance without adjustment for multiple testing. Analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software 9.4.

Results

Table 1 summarizes baseline demographic, immunologic, virologic and other baseline parameters of the 149 black and non-black populations. Overall, the median age was 32 years, 91% male, median CD4 count 342 cells/mm3 with 19% having CD4 count ≤ 200 cells/mm3. No participants were co-infected with hepatitis B or C. The median estimated dietary calcium and vitamin D intake at entry were 859 mg and 129 IU respectively; 17% and 21% of the participants reported calcium and vitamin D supplement use, respectively, within 30 days of study entry. The median BMD at the hip and at the spine were 1.06 g/cm3 and 1.13 g/cm3 (Z-scores 0.00 and −0.30) respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by race

| Race | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline parameters | Total (N=149) |

Black (N=52) |

Non-black (N=97) |

p-valuec | |

| Age (yrs) | Median (Q1 – Q3) | 32 (26 – 46) | 32 (25 – 46) | 32 (27 – 46) | 0.663 |

| Sex | M | 136 (91%) | 44 (85%) | 92 (95%) | 0.063 |

| F | 13 (9%) | 8 (15%) | 5 (5%) | ||

| Entry HIV-1 RNA (log10 copies/mL) | Median (Q1 – Q3) | 4.5 (4.1 – 5.0) | 4.4 (3.9 – 4.9) | 4.6 (4.2 – 5.1) | 0.098 |

| Entry CD4 count (cells/mm3) | Median (Q1 – Q3) | 342 (231 – 490) | 319 (241 – 431) | 347 (231 – 497) | 0.502 |

| Entry BMI (kg/m2) | Median (Q1 – Q3) | 24.4 (21.9 – 28.0) | 25.3 (22.4 – 30.1) | 24.2 (21.9 – 26.8) | 0.042 |

| Screening Vitamin D level (ng/mL) | Median (Q1 – Q3) | 24 (18 – 33) | 21 (14 – 24) | 26 (21 – 37) | <0.001 |

| Estimated dietary calcium intake (mg)a | Median (Q1 – Q3) | 859 (435 – 1,259) | 720 (433 – 1,219) | 934 (445 – 1,288) | 0.221 |

| Estimated dietary Vitamin D intake (IU)a | Median (Q1 – Q3) | 129 (59 – 264) | 124 (50 – 243) | 131 (64 – 271) | 0.310 |

| Calcium supplement useb | None | 124 (83%) | 45 (87%) | 79 (81%) | 0.444 |

| 10 – 100 | 6 (4%) | 3 (6%) | 3 (3%) | ||

| 101 – 250 | 16 (11%) | 4 (8%) | 12 (12%) | ||

| 251 – 500 | 3 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (3%) | ||

| Vitamin D supplement useb | None | 117 (79%) | 41 (79%) | 76 (78%) | 0.218 |

| 200 – 500 | 23 (15%) | 10 (19%) | 13 (13%) | ||

| 501 – 800 | 9 (6%) | 1 (2%) | 8 (8%) | ||

| Estimated sunlight exposure (UV index) | Median (Q1 – Q3) | 3.9 (3.5 – 5.3) | 3.5 (3.4 – 4.5) | 3.9 (3.5 – 5.3) | 0.013 |

| BMD at hip (g/cm2) | Median (Q1 – Q3) | 1.06 (0.96 – 1.18) | 1.10 (1.02 – 1.24) | 1.05 (0.93 – 1.11) | <0.001 |

| BMD at spine (g/cm2) | Median (Q1 – Q3) | 1.13 (1.02 – 1.22) | 1.17 (1.07 – 1.24) | 1.08 (0.99 – 1.19) | 0.003 |

| Z score for BMD at hip | Median (Q1 – Q3) | 0.00 (−0.80 – 0.50) | −0.20 (−0.80 – 0.50) | 0.10 (−0.70 – 0.60) | 0.576 |

| Z score for BMD at spine | Median (Q1 – Q3) | −0.30 (−1.10 – 0.50) | −0.20 (−1.15 – 0.55) | −0.40 (−1.00 – 0.50) | 0.707 |

Entry calcium and vitamin D dietary intake were estimated using a 3-day food recall calculator

Supplement use within 30 days of study entry

Exact Wilcoxon rank-sum p-values for continuous variables and Fisher's exact p-values for categorical variables

Baseline and change in total 25-(OH)D, VDBP, bioavailable 25-(OH)D, and PTH by treatment arm in all participants

At baseline, the distribution of levels of total 25-(OH)D (median (Q1, Q3) 28.4 (20.9, 38.5) vs 26.4 (19.6, 33.0) ng/mL), bioavailable 25-(OH)D (2.1 (1.6, 3.8) vs 2.1 (1.4, 3.3) ng/mL) and PTH (28.3 (24.5, 34.5) vs 27.6 (22.1, 33.9) pg/mL) appeared to be similar between VitD/Ca and placebo arms. Total 25-OHD increased from baseline to week 48 in the VitD/Ca arm (median (Q1, Q3) +24.2 (+14.3, +35.8) ng/mL) but not in the placebo arm (+0.6 (−6.1, +4.3) ng/mL); (p<0.001). Within arm increases in VDBP from baseline to 48 weeks were seen in both treatment groups (all p<0.005), but a difference between the VitD/Ca and placebo arms was not apparent (p=0.20). Bioavailable 25-(OH)D from baseline to 48 weeks increased significantly in the VitD/Ca arm (+1.5 (+0.5, +3.5) ng/ml, p<0.001), but not in the placebo arm (−0.1 (−0.5, +0.4) ng/ml, p=0.50); (between arm p<0.001). In contrast, PTH increased from baseline to 48 weeks in the placebo arm (+5.2 (−0.7, +12.6) pg/ml, p<0.001), but not in the VitD/Ca arm (+1.1 (−4.0, +6.1) pg/mL, p=0.40); (between arm p=0.004).

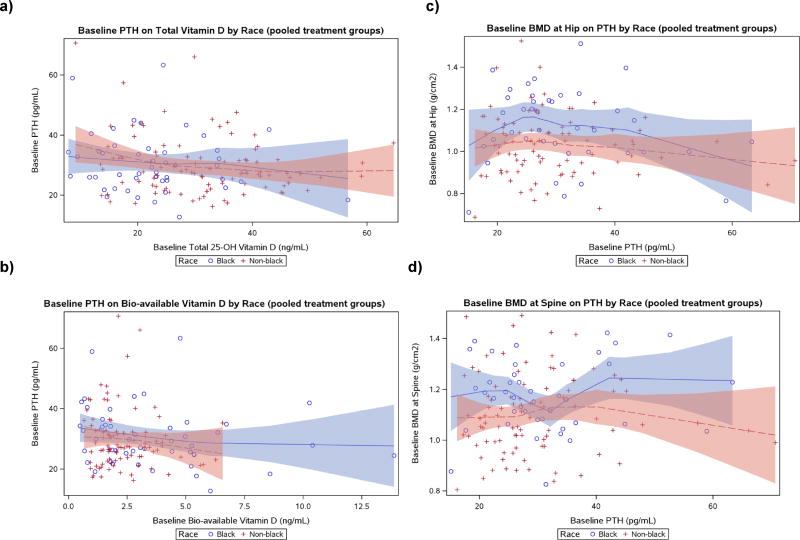

Baseline and change in total 25-(OH)D, VDBP, bioavailable 25-(OH)D, and PTH by race

At baseline, black participants had lower total 25-(OH)D [22.6 (15.8, 26.9) vs. 31.1 (23.1, 38.8) ng/ml, p<0.001] and VDBP [125.6 (79.0, 264.0) vs. 289.6 (207.7, 393.2) µg/ml, p<0.001], but higher bioavailable 25-(OH)D [2.9 (1.5, 5.2) vs. 2.0 (1.5, 3.0) ng/ml, p=0.022] than non-black participants (Table 2a). Black participants also had slightly higher BMI than non-black participants [25.3 (22.4, 30.1) vs 24.2 (21.9, 26.8) kg/m2, p=0.04]. Overall, a difference between the race groups in PTH levels was not apparent for any given 25-(OH)D level (Figure 1a). However, the relationship between bioavailable vitamin D and PTH revealed a different pattern: black participants tended to have modestly higher levels of PTH compared to non-black for any given level of bioavailable vitamin D at baseline (Figure 1b). Furthermore, for a given level of PTH, black participants tended to have higher levels of BMD both at hip and spine compared to non-black participants (Figure 1c and 1d).

Table 2.

| a Baseline and absolute change from 0 to 48 weeks by race within treatment group for total 25-(OH)D, Vitamin D binding protein (VDBP), bioavailable 25-(OH)D, and parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels. | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables Median (Q1, Q3) |

Baseline & Change 0–48 week |

Placebo | Vitamin D/calcium | ||||||

| Nblack / Nnon-black |

Black | Non-black | p | Nblack / Nnon-black |

Black | Non-black | p | ||

| Total 25OHD (ng/mL) | Baseline | 19 / 46 | 20.2 (16.0, 27.3) | 29.8 (22.2, 35.6) | 0.004 | 21 / 43 | 23.0 (14.6, 25.1) | 34.7 (23.1, 40.5) | 0.001 |

| Change | −2.5 (−6.3, 4.3) | 1.3 (−5.5, 4.7) | 0.25 | 32.2 (14.3, 42.6) * | 22.5 (14.2, 34.1) * | 0.27 | |||

| VDBP (ug/mL) | Baseline | 20 / 43 | 179 (92, 299) | 272 (181 ,353) | 0.007 | 20 / 40 | 93 (77, 255) | 313 (216 , 408) | <0.001 |

| Change | 25.9 (−4.8, 40.6) * | 11.2 (−6.9, 38.7) | 0.43 | 9.4 (−0.2, 28.3) | 27.0 (0.0, 60.0) * | 0.098 | |||

| Bioavailable 25OHD (ng/mL) | Baseline | 18 / 43 | 2.6 (1.4, 4.3) | 2.0 (1.4, 3.3) | 0.53 | 19 / 40 | 4.4 (1.8, 5.3) | 2.1 (1.6, 2.6) | 0.014 |

| Change | −0.1 (−1.4, 0.1) | 0.1 (−0.4, 0.5) | 0.063 | 3.9 (1.4, 7.3) * | 1.1 (0.4, 2.2)* | <0.001# | |||

| PTH (pg/mL) | Baseline | 22 / 47 | 28.9 (25.9, 34.0) | 27.1 (21.3, 33.1) | 0.44 | 22 / 43 | 27.5 (22.5, 35.5) | 28.0 (25.4, 32.4) | 0.89 |

| Change | 5.9 (−0.4, 12.2) * | 4.3 (−1.4, 12.3) * | 0.49 | −0.9 (−8.2, 4.2) | 1.7 (−1.9, 7.2) | 0.11 | |||

| b Baseline and percent change from 0 to 48 weeks by race within treatment group for BMD at the hip and spine and bone turnover markers. | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables Median (Q1, Q3) |

Baseline & Change 0–48 week |

Placebo | Vitamin D/calcium | ||||||

| Nblack / Nnon-black |

Black | Non-black | p | Nblack / Nnon-black |

Black | Non-black | p | ||

| BMD at Total Hip | Baseline (g/cm2) | 25 / 48 | 1.05 (0.99, 1.20) | 1.01 (0.90, 1.10) | 0.12 | 21 / 42 | 1.19 (1.05, 1.24) | 1.05 (0.96, 1.14) | 0.005 |

| %Change (%) | −2.52 (−4.83, −1.02)* | −3.21 (−5.54, −0.73)* | 0.85 | −1.46 (−3.86, 0.59) | −1.45 (−3.13, −0.70)* | 0.91 | |||

| BMD at Lumber Spine | Baseline (g/cm2) | 26 / 48 | 1.14 (1.06, 1.23) | 1.05 (0.96, 1.19) | 0.067 | 22 / 43 | 1.19 (1.08, 1.30) | 1.13 (1.02, 1.24) | 0.087 |

| %Change (%) | −2.43 (−4.07, −0.40)* | −3.09 (−4.84, −0.95)* | 0.79 | −1.76 (−3.78, 0.00)* | −1.41 (−4.29, −0.53)* | 0.87 | |||

| P1NP (ng/mL) | Baseline | 22 / 47 | 47 (38, 65) | 45 (34, 58) | 0.52 | 22 / 43 | 55 (44, 69) | 52 (40, 66) | 0.96 |

| Change | 17 (−1, 32)* | 18 (9, 42)* | 0.21 | 5 (−15, 49) | 15 (4, 29)* | 0.53 | |||

| CTX (ng/mL) | Baseline | 22 / 47 | 0.35 (0.26, 0.47) | 0.33 (0.24, 0.57) | 0.87 | 22 / 43 | 0.40 (0.29, 0.44) | 0.45 (0.32, 0.55) | 0.22 |

| Change | 0.19 (0.09, 0.42)* | 0.14 (0.02, 0.27)* | 0.24 | 0.08 (−0.10, 0.25) | 0.14 (0.00, 0.30)* | 0.90 | |||

p<0.05 within race group change from baseline.

p<0.05 difference between race groups (black vs. non-black) in change from baseline

Figure 1.

Scatter-plots of parathyroid hormone (PTH) on other parameters at baseline by race with LOESS fits

- Lines represent non-parametric smooth curves LOESS fits, with corresponding 95% confidence limits in shaded colors.

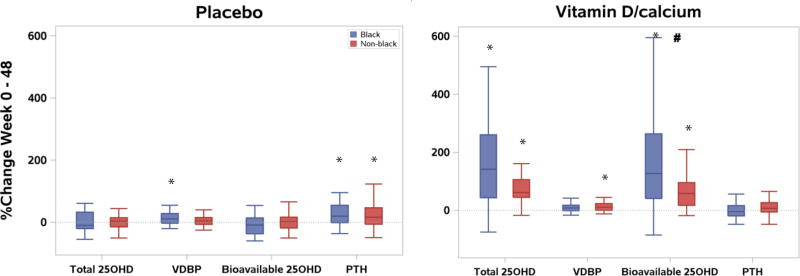

Among participants receiving VitD/Ca, increases in total 25-(OH)D and bioavailable 25-(OH)D levels from week 0 to 48 were observed in both blacks and non-black groups, but differences between race-groups were only apparent for bioavailable 25-(OH)D (p<0.001, Table 2a). Similarly, percentage increase from baseline in bioavailable 25-(OH)D over 48 weeks was also greater in black compared to non-black participants (Figure 2). While an increase in levels of VDBP from baseline was apparent among non-black participants, this was not apparent in black participants; a difference between the 2 racial groups was not evident (p=0.098). Changes in PTH from baseline were not apparent in either race group (Table 2a).

Figure 2.

Boxplots for percent change in 25-(OH)D, vitamin D binding protein (VDBP), bioavailable 25-(OH)D, and parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels by race and treatment arm

* Post-hoc Wilcoxon sign-rank p < 0.05 for within-race-group absolute change from baseline to week 48.

# Post-hoc Wilcoxon rank sum p<0.001 for difference in absolute change from baseline to week 48 between the two race groups.

Among participants who received placebo, no changes in 25-(OH)D or bioavailable 25-(OH)D were apparent from week 0 to 48 for either race group. While an increase in levels of VDBP from baseline was apparent among black participants, this was not apparent in non-black participants; a difference between the 2 racial groups was not evident (p=0.43). In contrast, an increase in levels of PTH was apparent in both race groups; the magnitude of this increase did not differ between groups (p=0.49) (Table 2a).

BMD, P1NP, and CTX by treatment arm and race

At baseline, BMD was higher in the black than the non-black group at the spine and hip, but Z scores did not differ between groups (Table 1). No differences between black and non-black groups in change in BMD were apparent in either the VitD/Ca or placebo arms (Table 2b). Similarly, there were no between-race differences in bone turnover marker response (P1NP and CTX) in either the VitD/Ca and placebo arms (Table 2b).

Examination of the relationships between 48-week increases in total or bioavailable 25-(OH)D and increases in hip or spine BMD or decreases in P1NP and CTX among those who received VitD/Ca revealed weak associations among non-black participants (r=0.306 to r=0.431, p<0.05) that were not apparent among blacks (all r<|0.40|, all p>0.15). Visual examination of these data in scatterplots with LOESS fits (supplementary Figure 1) highlight greater variability in total or bioavailable 25-(OH)D changes among blacks compared to non-blacks that contribute to this finding. Overall, the associations between change in bone outcomes and changes in bioavailable 25-(OH)D versus total 25-(OH)D appear consistent.

Discussion

With VitD/Ca supplementation, total and bioavailable 25-(OH)D levels increased over 48 weeks with beneficial effects on BMD in both black and non-black participants initiating ART. Despite having a total 25-(OH)D in the insufficient range (median <30ng/ml), black HIV-infected individuals had higher bioavailable 25-(OH)D and similar PTH values at baseline, and achieved greater increases in bioavailable 25-(OH)D with VitD/Ca supplementation compared to non-black participants. While changes in both total and bioavailable 25-(OH)D levels appeared to be weakly associated with bone outcomes among non-black participants, associations were not apparent for either measure among black participants. These data fail to confirm that bioavailable vitamin D is a more useful measure of vitamin D status compared to total 25-(OH)D in HIV-infected blacks initiating ART and receiving vitamin D and calcium supplementation.

The importance of measuring vitamin D levels in the setting of HIV infection has been hotly debated, particularly given the “epidemic” of hypovitaminosis D reported among HIV-infected persons (and the general population) despite unclear benefit beyond established BMD protection[13, 14]. The well characterized racial differences in total 25-(OH)D have created consternation among clinicians given the fact that black Americans tend to have higher BMD despite lower 25-(OH)D levels than whites. Furthermore, PTH levels have been reported lower for black Americans at any given 25-(OH)D level suggesting that either total vitamin D measurement may not reflect the active vitamin D metabolites or an alternative set point at which PTH expression increases [3]. The recognition that much of the measured vitamin D is actually bound to VDBP provides the opportunity to explain these discrepancies by estimating free or bioavailable vitamin D after measurement of VDBP levels.

Unfortunately, the measurement of VDBP has not been standardized. Recent studies suggest that the monoclonal antibody assay for VDBP (R&D Systems, Minneapolis MN), used by Powe and colleagues and in our study, detects a lower concentration of VDBP in black Americans due to a lower affinity for DBP/GC1f, which is commonly expressed in people of African origin, and a higher affinity for DBP/GC1s or DBP/GC12 which are commonly expressed in white individuals[8–10]. In contrast to findings reported with the monoclonal antibody assay, studies using an alternative polyclonal Ab assay [7–10], or liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry to directly measure VDBP [7, 15] have not found VDBP to be lower or bioavailable 25-(OH)D higher in black individuals. Currently, there is no consensus regarding which assay to use, or whether bioavailable 25-(OH)D is a better predictor of vitamin D status or clinical endpoints than total 25-(OH)D [5, 16, 17].

In the setting of HIV infection, two studies have reported an increase in both PTH and VDBP, using the monoclonal antibody assay, with initiation of TDF-containing ART [11, 12], but neither study calculated bioavailable 25-(OH)D or compared differences by race. Hsieh et al reported a 30% increase in median VDBP levels from 154 (91, 257.4) to 198.3 (119.6, 351.9) ug/ml in Chinese individuals after 48 weeks of EFV/FTC/TDF. Similarly, Haven et al reported an increase in VDBP using the monoclonal antibody assay with TDF-containing ART that corresponded to a decrease in free 1,25(OH)2D, suggesting a functional vitamin D deficiency induced by TDF[12]. Within the placebo arm of our study, modest (14%) increases in VDBP levels were apparent only among black participants and did not translate to a decrease in bioavailable 25-(OH)D. In contrast, within the VitD/Ca arm, an increase in VDBP from baseline was observed in the non-black group only, but increases in bioavailable 25-(OH)D were apparent in both black and non-black groups. Notably the increase in bioavailable 25-(OH)D within the VitD/Ca arm, was greater for black than non-black groups. Whether this fact relates back to the specific monoclonal antibody assay used or an actual difference in VDBP for these different groups cannot be determined based on available data. Since all participants received TDF, our data also cannot completely address the functional vitamin D defiency associated with TDF-exposure reported by Haven and colleagues. However, the observed increases in PTH in both race groups in the placebo but not the VitD/Cal supplementation arm are suggestive of a similar process.

While having total 25-(OH)D levels in the insufficient range (<30ng/ml), black participants had higher bioavailable 25-(OH)D at baseline, similar PTH levels, and greater increases in bioavailable 25-(OH)D with VitD/Ca supplementation than non-black participants. These data suggest that total 25-(OH)D levels do not uniformly indicate vitamin D deficiency. Previous studies have evaluated the relationship between total serum 25-(OH)D levels and PTH by race; in these studies, the inflection point in a LOESS curve, which represents the 25-(OH)D level above which PTH levels remain constant, occurs at a lower 25-(OH)D level in black compared to white individuals[18]. One can extrapolate that vitamin D sufficiency has a lower 25-(OH)D set point for black than white individuals and the accepted threshold for vitamin D deficiency (<20ng/ml 25-(OH)D) may not have the same physiological implications [3]. Our LOESS curves for total or bioavailable 25-(OH)D versus PTH did not reveal a clear inflection point in either blacks or non-black participants (Figure 1); however, overall, it appeared that for the same level of bioavailable 25 (OH) vitamin D at baseline, black participants tend to have a modestly, although not significantly, higher level of PTH at baseline compared to non-black participants.

We recognize that this study has limited power to confidently estimate the relationship between race, VDBP expression and bioavailable 25-(OH)D. Our analyses were limited to within subgroup analyses and were underpowered to formally assess effect modification via tests for interaction. To this end, we are conservative with our inferences, paying attention to effect size differences and not solely relying on subgroup tests of statistical significance, Another limitation of this secondary analysis is that we estimated bioavailable 25-(OH)D using a single assay, the monoclonal antibody test for VDBP, and did not compare results to the polyclonal antibody assay or directly measured bioavailable 25-(OH)D. Given the current controversies regarding the VDBP assays and the appropriate mechanism to measure bioavailable vitamin D, additional research is needed to establish best practices for determining these clinical parameters and their utility in bone health and beyond.

In conclusion, with Vit/Ca supplementation during ART initiation, we observed similar increases in total 25-(OH)D, but greater increases in calculated bioavailable 25-(OH)D in black compared to non-black participants when using a monoclonal assay to measure VDBP. VitD/Ca supplementation prevented BMD loss at both the spine and hip in both black and non-black participants. However the benefits of supplementation was not consistently reflected in outcomes of bioavailable 25-(OH)D by race. Given the current uncertainties with available VDBP assays, calculating bioavailable 25-(OH)D does not appear to provide benefit beyond measuring total 25-(OH)D for assessment of vitamin D status in black HIV-infected persons.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to gratefully acknowledge all of the study sites and study participants who have devoted their time and effort to this research endeavor.

Sources of Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UM1 AI068634, UM1 AI068636, UM1 AI106701, R01 AI095089 and supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR). “This publication was also supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Number UL1TR001873.The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases or the National Institutes of Health, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Gilead funded the DXA scans and ancillary laboratory testing. Study medications were provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, and Tischcon Corporation.

Footnotes

Trial registration number: NCT01403051

Conflicts of interest

Prior presentations:

This work was presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections 2016 (February 22–25, 2016, Abstract #700) in Boston, Massachusetts, USA

References

- 1.Overton ET, Chan ES, Brown TT, Tebas P, McComsey GA, Melbourne KM, et al. Vitamin D and Calcium Attenuate Bone Loss With Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation: A Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:815–824. doi: 10.7326/M14-1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cauley JA, Danielson ME, Boudreau R, Barbour KE, Horwitz MJ, Bauer DC, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and clinical fracture risk in a multiethnic cohort of women: the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:2378–2388. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gutierrez OM, Farwell WR, Kermah D, Taylor EN. Racial differences in the relationship between vitamin D, bone mineral density, and parathyroid hormone in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:1745–1753. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1383-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bikle DD, Gee E, Halloran B, Kowalski MA, Ryzen E, Haddad JG. Assessment of the free fraction of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in serum and its regulation by albumin and the vitamin D-binding protein. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986;63:954–959. doi: 10.1210/jcem-63-4-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powe CE, Evans MK, Wenger J, Zonderman AB, Berg AH, Nalls M, et al. Vitamin D-binding protein and vitamin D status of black Americans and white Americans. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1991–2000. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouillon R. Free or Total 25OHD as Marker for Vitamin D Status? J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31:1124–1127. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denburg MR, Hoofnagle AN, Sayed S, Gupta J, de Boer IH, Appel LJ, et al. Comparison of Two ELISA Methods and Mass Spectrometry for Measurement of Vitamin D-Binding Protein: Implications for the Assessment of Bioavailable Vitamin D Concentrations Across Genotypes. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31:1128–1136. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nielson CM, Jones KS, Bouillon R, Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Research G. Chun RF, Jacobs J, et al. Role of Assay Type in Determining Free 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels in Diverse Populations. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1695–1696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1513502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nielson CM, Jones KS, Chun RF, Jacobs JM, Wang Y, Hewison M, et al. Free 25-Hydroxyvitamin D: Impact of Vitamin D Binding Protein Assays on Racial-Genotypic Associations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:2226–2234. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henderson CM, Lutsey PL, Misialek JR, Laha TJ, Selvin E, Eckfeldt JH, et al. Measurement by a Novel LC-MS/MS Methodology Reveals Similar Serum Concentrations of Vitamin D-Binding Protein in Blacks and Whites. Clin Chem. 2016;62:179–187. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.244541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsieh E, Fraenkel L, Han Y, Xia W, Insogna KL, Yin MT, et al. Longitudinal Increase in Vitamin D Binding Protein Levels after Initiation of Tenofovir/Lamivudine/Efavirenz among Individuals with HIV. AIDS. 2016 doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Havens PL, Kiser JJ, Stephensen CB, Hazra R, Flynn PM, Wilson CM, et al. Association of higher plasma vitamin D binding protein and lower free calcitriol levels with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate use and plasma and intracellular tenofovir pharmacokinetics: cause of a functional vitamin D deficiency? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:5619–5628. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01096-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dao CN, Patel P, Overton ET, Rhame F, Pals SL, Johnson C, et al. Low vitamin D among HIV-infected adults: prevalence of and risk factors for low vitamin D Levels in a cohort of HIV-infected adults and comparison to prevalence among adults in the US general population. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:396–405. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hidron AI, Hill B, Guest JL, Rimland D. Risk factors for vitamin D deficiency among veterans with and without HIV infection. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124168. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aloia J, Dhaliwal R, Mikhail M, Shieh A, Stolberg A, Ragolia L, et al. Free 25(OH)D and Calcium Absorption, PTH, and Markers of Bone Turnover. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:4140–4145. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnsen MS, Grimnes G, Figenschau Y, Torjesen PA, Almas B, Jorde R. Serum free and bio-available 25-hydroxyvitamin D correlate better with bone density than serum total 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2014;74:177–183. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2013.869701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jemielita TO, Leonard MB, Baker J, Sayed S, Zemel BS, Shults J, et al. Association of 25-hydroxyvitamin D with areal and volumetric measures of bone mineral density and parathyroid hormone: impact of vitamin D-binding protein and its assays. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27:617–626. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3296-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hannan MT, Litman HJ, Araujo AB, McLennan CE, McLean RR, McKinlay JB, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and bone mineral density in a racially and ethnically diverse group of men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:40–46. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.