Abstract

Background

The U.S. primary care system is under tremendous strain to deliver care to an increased volume of patients with a concurrent primary care physician shortage. Nurse Practitioner (NP)-physician co-management of primary care patients has been proposed by some policymakers to help alleviate this strain. To date, no collective evidence demonstrates the effects of NP-physician co-management in primary care.

Purpose

This is the first review to synthesize all available studies that compare the effects of NP-physician co-management to an individual physician managing primary care.

Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) framework guided the conduct of this systematic review. Five electronic databases were searched. Titles, abstracts, and full texts were reviewed and inclusion/exclusion criteria applied to narrow search results to eligible studies. Quality appraisal was performed using Downs and Black’s quality checklist for randomized and nonrandomized studies.

Results

Six studies were identified for synthesis. Three outcome categories emerged: 1) PCP adherence to recommended care guidelines; 2) empirical changes in clinical patient outcomes; and 3) patient/caregiver quality of life. Significantly more recommended care guidelines were completed with NP-physician co-management. There was variability of clinical patient outcomes with some findings favoring the co-management model. Limited differences in patient quality of life were found. Across all studies, the NP-physician co-management care delivery model was determined to produce no detrimental effect on measured outcomes, and in some cases, was more beneficial in reaching practice and clinical targets.

Practice Implications

The use of NP-physician co-management of primary care patients is a promising delivery care model to improve the quality of care delivery and alleviate organizational strain given the current demands of increased patient panel sizes and primary care physician shortages. Future research should focus on NP-physician interactions and processes to isolate the attributes of a successful NP-physician co-management model.

Keywords: Teamwork, Primary Care, Nurse Practitioners, Systematic Review, Co-Management

Introduction

Primary care physician shortages, an increase in the number of insured patients, rising healthcare costs, and the epidemic of chronic disease, continue to pose a strain on the United States (US) primary care system (Bodenheimer & Pham, 2010; Mitka, 2007). Primary care plays a vital role in our health care system as it serves as the first point of contact for patients to access care services and focuses on addressing a variety of patient needs, particularly to those with chronic conditions (Halcomb et al., 2005; Starfield, Shi, & Macinko, 2005). For example, by 2020, an estimated 157 million Americans will be living with a chronic disease who will need timely and high quality primary care to manage their conditions; yet current care models are threatened by primary care physician shortages that are expected to reach a 40,000 physician deficit over the next five years (Lopez, Mathers, Ezzati, Jamison, & Murray, 2006; Wu & Green, 2000).

In traditional care models, a single physician individually manages a primary care patient panel, which is a subgroup of the population assigned to a single primary care provider (PCP) by respective insurance carriers (Murray, 2007). However, as patient panel sizes are increasing, it is estimated that it takes an unrealistic 21 hours per day for a single PCP to complete all recommended care guidelines in primary care (Yarnall, Ostbye, Krause, Pollak, Gradison, & Michener, 2009). Thus, policy makers are calling for ways to alleviate this burden and assure that patients have access to high quality primary care through the investigation of various care delivery models.

The implementation of team-based care models have been proposed by policy makers, researchers, and clinicians, as one option for care delivery in primary care organizations (Bodenheimer, Ghorob, Willard-Grace, & Grumbach, 2014). In one type of team, organizations are integrating nurse practitioners (NPs) into care delivery to help alleviate the challenges facing our health care system as NPs are capable of delivering high quality care (Stanik-Hutt et al., 2013). Individual NP care has been found to provide care equivalent to physicians in terms of achieving the same clinical outcomes and with favorable patient satisfaction (Lenz, Mundinger, Kane, Hopkins, & Lin, 2004). However, to date, while many studies have examined the primary care outcomes of an individual physician or an individual NP, this is the first review to examine the potential of NP-physician co-management of primary care patients and its impact on patient outcomes and care delivery.

The NP workforce currently has the fastest growth rate of all health care professions in the U.S. and is projected to continue its growth well over the next decade marking its potential to help alleviate some strain of delivering primary care (Auerbach, 2012). Eighty four percent of currently licensed NPs in the United States (U.S.) are educationally prepared, trained, and certified to work in primary care settings (AANP, 2015). Furthermore, a recent survey shows that 74% of primary care physicians and 88% of primary care NPs would ideally prefer to work in a practice of both NPs and physicians (Buerhaus, DesRoches, Dittus, & Donelan, 2015). There is a discrepancy of perspectives, however, regarding NP reimbursement rates, hospital admitting privileges and having a NP lead a medical home (Donelan, DesRoches, Dittus, & Buerhaus, 2013). For example, a recent systematic review found potential for cost savings when NPs complement physician-based care (Martin-Misener et al., 2015). Yet, while the American College of Physicians (ACP) (2009) supports the expansion of NP scope of practice to help alleviate the strain in primary care, other medical organizations firmly believe that primary care patients should be strictly physician-managed (American Academy of Family Physicians, 2012). Despite this variability of perceptions of the NP role, the overarching question remains whether the quality of care and clinical outcomes are improved, maintained, or negatively impacted, when a patient is co-managed by a NP and physician, together, sharing the responsibility of patient care for the same primary care patient. In this review, we define co-management as two types of PCPs jointly sharing the responsibility and workload required for achieving optimal patient care management and outcomes. Co-management can be viewed as a subset of team-based care that is focused on more than one PCP integrated within the team, rather than a single physician, who equally oversee the management of a patient. The purpose of this study is to identify and synthesize all available studies that explore the outcomes of NP-physician co-management compared to a traditional single physician managing care.

Theory

The Conceptual Framework for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice (ICP) guided this systematic review (Stutsky & Spence Laschinger, 2014). The ICP framework is centered around four dimensional constructs that lead to increased collaborative practice between different types of professions: collective ownership of goals; interdependence; knowledge exchange; and understanding of roles. The first dimension, collective ownership, involves active participation of all providers and patients in achieving mutual goals for patient care. The second, knowledge exchange, includes the sharing of information that is vital to the care of the patient and includes a provider’s willingness to do so. The third dimension highlights that an understanding of individual provider roles (e.g. NP versus physician) is vital and includes the identification, appreciation, and subsequent respect of each discipline’s value in patient care. The final dimension, interdependence, includes the reciprocal reliance of provider interaction to reach mutual goals. It also encompasses the need to examine the level of equality of power within the relationship. When all four dimensions are present collectively, provider work behaviors and satisfaction are optimized and as a result, patient safety, patient outcomes, and the quality of care is enhanced.

Upon application of the ICP framework to our research question we decided to focus our PCP co-management type to NPs and physicians. Although other types of PCPs, such as physician assistants, deliver high quality primary care, their scope of practice often involves one of physician oversight of tasks and clinical patient care decisions. NPs, on the other hand, can currently practice independently of physicians in 26 U.S. states (AANP, 2015). Since the ICP framework highlights the importance of equality of provider roles, we deemed it important to examine co-management effects of two types of PCPs that have the most potential in holding equal organizational decision making. Therefore, we focused this review on NP- and physician-PCP disciplines. Using this ICP framework, we hypothesize that NPs and physicians can collaboratively co-manage patients and enhance the quality of care delivered in a primary care setting.

Methods

Search Strategy

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRIMSA) framework guided the conduct of this systematic review (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & Group, 2009). Comprehensive search strategies were developed and applied during the electronic search of five databases: MEDLINE, PubMed, CINAHL, EMBASE and Cochrane. A search for grey literature was also conducted in an effort to identify unpublished studies and/or conference abstracts. Keywords searched included ‘team,’ ‘teamwork,’ ‘interprofessional,’ ‘nurse practitioner,’ ‘advanced practice nurse,’ ‘primary care,’ and ‘primary healthcare’ and ‘co-management.’

Sample Selection

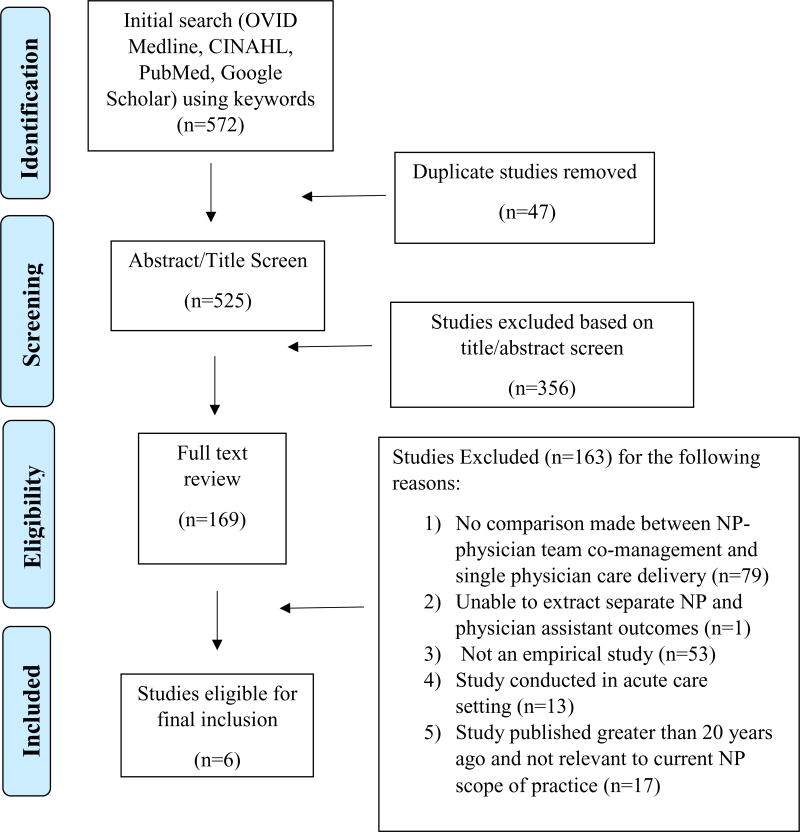

The initial literature search yielded 572 studies which were imported into reference management software, Endnote. Forty-seven duplicates were removed, leaving 525 records for screening. Two investigators reviewed the abstracts and titles of the remaining articles and applied the following inclusion criteria: 1) The use of a team-based care delivery care model; 2) The study was conducted in a primary care ambulatory setting; 3) A NP was a member of the infrastructure of the team; and 4) The study was conducted in the US. Given that NP roles, responsibilities, and scope of practice often differ across countries, this search was limited to studies conducted in the US. One hundred sixty-nine studies met eligibility for full text review. Next, four researchers applied the following exclusion criteria during full text review: 1) No comparison made between a NP-physician team that co-manages patients and a single physician delivering patient care (n=79); 2) Unable to extract separate NP and physician assistant outcomes (n=1); 3) Not an empirical study (e.g. opinion editorials) (n=53); 4) Studies conducted strictly in the acute care setting (n=13); and 5) Studies conducted more than 20 years ago (n=17). The studies that were published greater than 20 years ago were deemed by the authors as not relevant to current NP scope of practice regulations. Six studies remained for final inclusion. Although some studies included in the final synthesis do not exemplify the highest level of evidence (e.g. case study), they are the only studies that met the criteria of this review and are the most current available evidence meeting this study’s purpose. A PRISMA flow diagram of the literature search strategy is presented in Figure 1. Table 1 outlines the characteristics of each individual study including the aim, design, sample, study quality, setting, measures, and key findings.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram of Literature Search

Table 1.

Study Characteristics

| Study | Characteristics & Quality Appraisal | Outcome | Measure | Effect | NP-Physician Co-management | Physician-led care | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fortinsky et al. (2014) | Design: RCT Purpose: To determine the efficacy of a nurse practitioner intervention called “Proactive Primary Dementia Care” on health-related outcomes in patients and family members, as well as the acceptability of the intervention based on satisfaction expressed by physicians, patients and caregivers. |

Recommended Guidelines Adherence |

Did Not Measure | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Clinical | NPI | Median | ||||||

| Outcome | 6 months | 3 | 3 | .59 | ||||

| 12 months | 9 | 3.5 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Quality of Life | QOL-AD | Median | ||||||

| 6 months | 39 | 41 | .95 | |||||

| 12 months | 37 | 40 | ||||||

| CES-D | ||||||||

| 6 months | 5 | 4.5 | .80 | |||||

| 12 months | 6 | 2 | ||||||

| Symptom Management Self Efficacy |

||||||||

| 6 months | 39 | 45 | .92 | |||||

| 12 months | 37 | 44.5 | ||||||

| Sample: 31 patients | Support Service Self Efficacy |

|||||||

| Quality Appraisal: Medium (Score: 22) | 6 months | 36 | 38 | .14 | ||||

| 12 months | 35 | 38 | ||||||

| Zarit-Burden | ||||||||

| 6 months | 10 | 3 | .60 | |||||

| 12 months | 10 | 3 | ||||||

| Ganz et al. (2013) | Design: RCT | Recommended | Care Guidelines | % Met | ||||

| Guidelines | Dementia | 51 | 30 | <.001 | ||||

| Purpose: To determine whether NP-physician co-management improves quality of care | Adherence | Depression | 51 | 28 | .07 | |||

| Falls | 44 | 17 | .00 | |||||

| Heart Failure | 82 | 71 | .06 | |||||

| Incontinence | 58 | 26 | .01 | |||||

| All diagnoses | 54 | 34 | <.001 | |||||

| Sample: 200 patients | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Quality Appraisal: High (Score: 23) |

Clinical Outcome | Did Not Measure | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Quality of Life | Did Not Measure | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Reuben et al. (2013) | Design: Case Study | Recommended | Care Guidelines | % Met | ||||

| Guidelines | Overall | 71 | 35 | <.001 | ||||

| Purpose: To determine if community-based NP-physician co-management improves the quality of care for geriatric conditions: falls, urinary incontinence, dementia, and depression. | Adherence | |||||||

| Falls | 78 | 32 | ||||||

| Incontinence | 66 | 20 | ||||||

| Dementia | 59 | 38 | ||||||

| Depression | 63 | 60 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Clinical Outcome | Did Not Measure | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Sample: 485 patients | Quality of Life | Did Not Measure | ||||||

| Quality Appraisal: High (Score: 24) | ||||||||

| Ohman-Strickland et al. (2008) | Design: Cross Sectional | Recommended | Guidelines | % Met | ||||

| Purpose: To assess whether the quality of diabetes care differs among practices employing NPs, PAs, or neither, and which practice attributes contribute to any differences. | Guidelines | HbA1C | 65.5 | 48.9 | <.001 | |||

| Adherence | Blood Pressure | 80.1 | 83.2 | .63 | ||||

| Lipids | 80.1 | 68.3 | .007 | |||||

| Microalbumin | 31.9 | 18.6 | .10 | |||||

| Treatment Guidelines | ||||||||

| HbA1C | 98.2 | 100 | N/A | |||||

| Blood Pressure | 76.1 | 78.3 | .72 | |||||

| Lipids | 76.6 | 65.7 | .03 | |||||

| Microalbumin | 79.6 | 65.7 | .11 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Sample: 846 patients with diabetes 46 Practices | Clinical Outcome | Target Attainment | ||||||

| HbA1C | 50.7 | 44.5 | .36 | |||||

| Blood Pressure | 36.5 | 47.3 | .13 | |||||

| Quality Appraisal: Medium (Score: 19) | Lipids | 53.5 | 54.4 | .85 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Quality of Life | Did Not Measure | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Callahan et al. (2006) | Design: RCT Purpose: To determine the effectiveness of a collaborative care model with an interdisciplinary team to improve the quality of care for patients with Alzheimer’s Disease in primary care. |

Recommended Guidelines Adherence |

Did Not Measure | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Clinical Outcomes | NPI | MD (SD) | ||||||

| 6 months | 9.4 (12.9) | 11.1 (16.4) | .61 | |||||

| 12 months | 8.0 (12.0) | 16.1 (19.4) | .01 | |||||

| 18 months | 8.4 (10.2) | 16.2 (18.7) | .01 | |||||

| # NPI Modules ≥ 1 | ||||||||

| 6 months | 2.7 (2.6) | 2.9 (2.4) | .75 | |||||

| 12 months | 2.5 (2.5) | 3.5 (2.7) | .05 | |||||

| 18 months | 2.3 (2.4) | 3.6 (2.8) | .02 | |||||

| Sample: 154 patients | CSDD | |||||||

| 6 months | 4.3 (6.0) | 5.2 (5.4) | .65 | |||||

| Quality Appraisal: High (Score: 25) | 12 months | 3.5 (3.9) | 5.8 (5.9) | .17 | ||||

| 18 months | 4.2 (3.9) | 5.4 (4.4) | .94 | |||||

| Telephone Cognitive Interview | ||||||||

| 6 months | 16.9 (8.8) | 16.0 (7.1) | .46 | |||||

| 12 months | 16.7 (8.9) | 14.6 (8.2) | .22 | |||||

| 18 months | 16.0 (9.5) | 15.3 (9.0) | .93 | |||||

| ADCSG ADLs | 49.3 (8.8) | 47.0 (16.7) | .73 | |||||

| 48.6 (17.7) | 44.6 (17.0) | .44 | ||||||

| 45.7 (20.1) | 42.1 (16.8) | .18 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Quality of Life | Total Caregiver NPI | MD (SD) | ||||||

| 6 months | 4.4 (6.4) | 5.7 (7.2) | .92 | |||||

| 12 months | 3.5 (5.8) | 7.7 (8.7) | .03 | |||||

| 18 months | 4.6 (6.3) | 7.4 (9.7) | .33 | |||||

| Caregiver Patient | ||||||||

| 6 months | 3.6 (5.0) | 4.3 (5.1) | .50 | |||||

| 12 months | 3.1 (3.9) | 4.6 (5.6) | .21 | |||||

| 18 months | 3.1 (4.5) | 5.2 (5.3) | .02 | |||||

| Litaker et al. (2003) | Design: RCT | Recommended | Care Guidelines | MD | ||||

| Guidelines | Influenza vaccination | 62 | 37 | <.001 | ||||

| Purpose: To compare a traditional physician-only model of care with a more collaborative, team based approach to chronic disease management (hypertension & diabetes management) | Adherence | Pneumovax | 32 | 12 | <.001 | |||

| Foot exam | 79 | 28 | <.001 | |||||

| Eye exam | 62 | 53 | .10 | |||||

| Smoking cessation | 13 | 3 | <.001 | |||||

| Education | ||||||||

| Exercise | 79 | 42 | <.001 | |||||

| Sodium restriction | 77 | 31 | <.001 | |||||

| Alcohol moderation | 16 | 5 | <.001 | |||||

| Sample: 156 | Medication side effects | 79 | 38 | <.001 | ||||

| Weight control | 79 | 59 | <.001 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Quality Appraisal: High (Score: 25) | Clinical Outcomes | Medication Adherence | MD | 79 | 74 | .06 | ||

| Laboratory Values | ||||||||

| HgbA1C | −0.68 | −0.15 | .02 | |||||

| HDL | 3 | 0.4 | .02 | |||||

| Total cholesterol | −10.8 | −9.89 | .85 | |||||

| Vital Signs | # patients meeting target | |||||||

| Blood Pressure (BP) | 11 | 10 | .84 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Quality of Life | Physical Component | MD | 0.5 | −1.27 | .19 | |||

| Mental Component Diabetes QOL |

3.27 | 1.13 | .17 | |||||

| Life satisfaction | 9.18 | 3.76 | .04 | |||||

| Life impact | 1.46 | 0.39 | .39 | |||||

| Social worry | 2.3 | 1.73 | .81 | |||||

| Life worry | 1.3 | 0.59 | .80 | |||||

MD: mean difference; AF: absolute frequency; RCT: Randomized Control Trial; pt.: patient; QOL: quality of life; SD: standard deviation; ADLs: Activities of daily living; ADSC: Alzheimers disease cooperative study group; NPI: Neuropsychiatric; Inventory; CSCC: Cornell Scale for Depression in

Quality Appraisal

The Downs and Black (1998) checklist for measuring quality of both randomized and nonrandomized studies was applied to each of the included studies. This tool contains 27 items with ‘yes,’ ‘no,’ or ‘not applicable’ responses to assess each study’s overall quality (10 items), external validity (3 items), study bias (7 items), confounding and selection bias (6 items), and power of the study (1 items). The creators of the tool designated a predetermined score for each item’s response that yields a potential maximum score of 30. The higher the score, the higher the quality of the study. Two investigators independently appraised each study using the checklist and then compared each item’s score in an attempt to reach a conclusive agreement of the study’s quality. If a consensus was not reached on a particular item of the checklist, a third researcher was asked to determine the final assessment. Study quality was classified as low quality/high risk of bias (score 1–11), medium quality/unclear risk of bias (12–22), and high quality/low risk of bias (23–30).

Results

Six studies were eligible for inclusion in the review and consisted of randomized control trials (n=4), a cross sectional study (n=1), and a case study (n=1). The most common investigated diagnoses in the included studies were Alzheimer’s dementia, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension. All studies compared outcomes of co-management by NP-physician teams and individual physician-led care delivery for primary care patients.

Outcome Measures

There were three outcomes that emerged from the studies; 1) PCP adherence to recommended care guidelines; 2) empirical changes in clinical patient outcomes; and 3) self-reported quality of life for the patient and their caregiver. Not every outcome was measured in every study, yet this is the only evidence currently available surrounding NP-physician co-management of primary care patients and the researchers deemed it important to analyze and assess all three outcomes in order to make recommendations for practice implications and future research. The first category, adherence to recommended care was measured as the percentage of compliance in following recommended practice guidelines that have previously been found to support optimal patient outcomes. For example, the percentage of a patient with diabetes receiving a recommended vaccination or annual ophthalmologic examination. The second category, clinical outcomes, includes changes in diagnosis-specific empirical measurements such as vital signs or laboratory values that are measured during a visit to assess how well a disease is being controlled, such as a change in blood pressure in a patient with hypertension. In patients with Alzheimer’s disease, clinical cognitive changes were assessed using the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia to measure changes in mood, behavior, and physical change. Behavior change was also measured using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), a widely-used instrument in clinical trials of anti-dementia medications. The third category, self-reported quality of life was measured across the studies using various instruments to scale the level of self-reported quality of life reported by patients when being treated for a particular diagnosis. The quality of life of caregivers was also evaluated. The synthesized results of each category are described below:

Adherence to Recommended Care Guidelines

Four studies evaluated and compared how NP-physician co-management of patient care impact compliance with completing recommended care guidelines (Ganz et al., 2010; Litaker et al., 2003; Ohman-Strickland et al., 2008; Reuben et al., 2013). In patients with hypertension, elevated cholesterol, and/or diabetes, several diagnosis-specific care guidelines are recommended to improve the quality of care delivered by the PCP in an effort to improve patient outcomes. For example, Reuben et al. (2013) found that 71% of overall recommended guidelines were completed with NP-physician co-management compared to 35% completed by a single physician (p<.001). This study was rated by the researchers as high quality, with limited bias identified. It is important to note that there was variability in the referral of patients to NPs for co-management of patient care, which was described as the result of patient preference or the unwillingness of physicians to make the referral.

Ganz et al. (2010) also found that a higher percentage of completed guidelines favored the NP-physician teams, specifically in patients with dementia (p<.001), falls (p=.00), incontinence (p=.01) and all diagnoses (p<.001). This study had a sample size of 200 patients and was conducted using rigorous methodology that scored as low risk of bias during quality appraisal. Litaker et al. (2003) found that recommended influenza and pneumonia vaccinations for patients with chronic disease such as diabetes was more likely to be completed by NP-physician teams (p<.001). Also, recommended smoking cessation and foot examinations were more likely to be performed (p<.001). There was no difference in the incidence of recommended completion of an annual eye exam by an ophthalmologist (p=.10). Patient education was also more likely to be completed such as dietary and activity recommendations that included sodium reduction (p<.001), moderation in alcohol consumption (p<.001), and weight control or reduction (p<.001). While medication side effects were discussed more by NP-physician teams, there was no difference between groups in the occurrence of medication compliance conversations. This study was appraised as high quality by the researchers with a low risk of bias. They demonstrated external validity and a clear effort to reduce bias and confounders. A small sample size (n=156) was identified as a threat to generalizability.

Ohman-Strickland et al. (2008) examined the occurrence of recommended chronic disease assessment or monitoring specifically for diabetic patients. This was a large study across 46 practice sites and included 846 patients with diabetes. The researchers reviewed charts to determine the adherence to American Diabetes Association guidelines, such as measuring glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) percentages or lipid levels that assess disease control. The PCPs in the study included NPs, physicians, and physician assistants. For the purpose of this review, we extracted only data relevant to physicians and NPs. The study found that significantly more patients were monitored for diabetic control (p<.001) and hyperlipidemia (p=.007) when co-managed by NPs and physicians compared to a single physician managing care. No difference was found for blood pressure monitoring (p=.63). This study was identified as medium quality by the researchers. There was limited information about the patients in this study and therefore it was hard to determine uniformity of the sample at baseline. Also, given the large amount of practices evaluated, we felt it possibly introduced bias and confounders surrounding a patient’s exposure to different team members, care processes, and facility resources. Despite the researcher’s attempt to adjust for potential confounders for organizational attributes and practices, we felt this variability could introduce influence a provider’s compliance with recommended care guidelines.

Empirical Changes in Clinical Outcomes

Four studies examined clinical outcomes achieved by NP-physician teams compared to a single physician and were reported as empirical changes in laboratory values or vital signs. (Callahan et al., 2006; Fortinsky et al., 2014; Litaker et al., 2003; Ohman-Strickland et al., 2008) Overall, studies presented either an improvement of clinical outcomes with NP-physician co-management or outcomes equivalent to care managed by a single physician. Two studies compared the decrease of the patient’s HbA1c percentages, used as an indicator of diabetic control, with the goal of decreasing the level to a percentage that is a recommended clinical target. In the first study, Litaker et al. (2003) reported a favorable reduction in the HbA1c level by 0.63% among patients cared for by NP-physicians teams compared to a 0.15% reduction among patients treated solely by a physician (p=.02) (Litaker et al., 2003). Given the narrow window of HbA1c percentage for diabetic control, we felt this was clinically significant. This study was appraised as high quality and used rigorous methods to ensure a low risk of bias especially with attention to selection of patients by assessing their baseline medical complexity and baseline medication use.

In the second study, the attainment of HbA1c targets lacked a significant difference (p=.36) (Ohman-Strickland et al., 2008). As previously mentioned, however, although this second study was much larger, the introduction of potential bias across the 46 practice sites could have potentially influenced the attainment of diabetic targets based on provider resources. In addition, there was no uniformity of patient medications prior to the start of the intervention.

These same two studies measured whether patients with hypertension and hyperlidemia achieved the intended clinical target for blood pressure (SBP<130 mmHg; DBP<85 mmHg) and lipid levels (LDL-cholesterol ≤ 100 mg/dL) and neither found a significant difference between patients co-managed and patient managed by an individual physician (blood pressure: p=.839, p=.13; lipid: p=.85, p=.78) (Litaker et al., 2003; Ohman-Strickland et al., 2008). Litaker et al. (2003) did however find significantly more patients with a beneficial increase of their high-density lipoproteins (HDL) levels (p=.02).

Clinical outcomes for patients with Alzheimer’s disease were investigated in two studies using the Cornell Scale and NPI that scores cognitive and behavior impairment. The first study, Callahan et al. (2006), was rated as high quality by the researchers with low risk for bias. Their study included blinded randomization of physicians to either managing patient care single handedly or co-managing with a NP. They found no statistically significant cognitive and behavior changes using the Cornell Scale of Depression for Dementia after 18 months (p=.94) or following a telephone interview assessment for cognition (p=.93). Using the NPI as the assessment tool, however, they found a significant increase in patient behavior (p=.01). Fortinsky et al. (2014) also used the NPI to assess patient behavior and found no statistically significant changes between the patients managed by NP-physician co-management and physicians alone (p=.18). During quality appraisal, this study was deemed medium quality with a potential risk for bias. The sample size was extremely small (n=31) questioning generalizability and the possibility that due to the small sample size there was not enough power to detect differences between groups.

Patient/Caregiver Quality of Life

Three studies investigated self-reported patient and caregiver quality of life (Callahan et al., 2006; Fortinsky et al., 2014; Litaker et al., 2003). Caregiver quality of life was measured using two tools, NPI and Caregiver Patient Health questionnaire, and administered concurrently at either 6, 12, and/or 18 months. There was no statistical significance between groups for caregiver quality of life at 6 and 12 months, yet an improvement was noted by 18 months (p=.02) (Callahan et al., 2006). Similarly, Fortinsky et al. (2014) found no statistical significance at 6 and 12 months yet there was no 18 month follow up assessment for comparison. Again, their small sample size and shorter follow up compared to the other studies may have inhibited finding significance. In the same study, neither care delivery model produced a superior increase in quality of life for patient with dementia (p=.95).

A third rigorous study, appraised as high quality by the researchers, found an increase in self-reported quality of life in patients with diabetes, specifically life satisfaction, and favoring those being treated within a co-management model (p=.04). All other quality of life measures, such as diabetes quality of life impact, social worry, or life worry, were found to be not significantly different between types of care delivery (Litaker et al., 2003).

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to determine the effects of NP-physician co-management in primary care in comparison to care delivered by an individual physician. Three outcome categories emerged from the studies: PCP adherence to recommended care guidelines; empirical changes in clinical patient outcomes; and patient or caregiver quality of life. It is evident from the literature search that with only six studies available, the investigation of this type of care delivery is still very premature. The findings of this review, however, shed light on the promise of co-management to help organizations meet the demand for care by adhering to recommended care guidelines and maintaining the quality of care. For example, significantly more guidelines were completed for patients with Dementia, Falls, and Incontinence. Further, patients with diabetes were more likely to have their Hgba1c and lipids monitored for changes, as well as receive recommended vaccinations. The application of, and compliance with, these recommended care guidelines is essential for the earlier detection of disease, decreased diagnosis-specific complications, reduced hospitalizations, and reduced health care spending (Penning-van Beest et al., 2007).

Clinically, there was a variability of results for empirical patient outcomes when comparing NP-physician co-management and a single physician managing care. For example, while some patients that were co-managed had a significantly greater reduction in target A1c levels for diabetic patients, other studies found no difference. The improvement may be attributed to the aforementioned increase in PCP adherence to recommended care guidelines given that an increased incidence of diabetic education, such as dietary and nutritional recommendations, has been found to improve patient outcomes, including HbA1c levels (Padgett, Mumford, Hynes & Carter, 1988). Yet, the lack of consistent findings across studies remains, thus suggesting that there may be differences in NP-physician co-management interactions or processes; something worth investigating and recommended as future research. Further, it is unknown whether the patients in the studies were being treated with the same medications to control total cholesterol levels and blood pressure. Only one study reported an effort to control for baseline medications but only by the number of medications and not by pharmaceutical class or mechanism of action. This lack of knowledge potentiates a variability in treatment modalities that could skew the reduction of empirical clinical changes in patients. A study that controls for baseline blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and medications, is recommended.

The lack of the co-management process or PCP interaction descriptions were evident across all studies and could have potentiated the variability of the included studies’ findings in this review. Most noteworthy, there remains a lack of instruments that assess PCP interactions with each other, and with patients or caregivers, within a co-management model and needed to optimize the care that is delivered. For example, there was limited to no description of how NPs and physicians allocated tasks between each other or what type of ancillary support or resources were available to each PCP. As primary care continues to be delivered in team-based environments, a closer look at PCP relationships and interactions could benefit the implementation and future investigation of co-management care delivery.

In summary, this review demonstrates promising evidence that the integration of NPs and physicians in a co-management care model is as effective as a single physician managing a primary care patient. This finding highlights a potential solution to overcoming some of the primary care strain of managing larger patient panel sizes while maintaining the quality of care. It is important to note that individual outcome categories were not examined across all studies and were predominantly limited to two to three studies each. This further illuminates that this emerging care model requires additional research to determine its long-term effect on primary care.

Practice Implications

The findings of this systematic review suggest significant practice, policy, and research implications. First, in terms of practice, the implementation of a NP-physician co-management care model increases the ability of primary care organizations to adhere to recommended clinical care guidelines. It is unclear whether the increase that is demonstrated in this review is due to an increase in the number of PCPs available to the patient or the combination of individual discipline values (medicine and advanced practice nursing) that contribute to patient care. Regardless, an increase in adherence will improve the quality of patient care delivered, as guidelines are based on the most current evidence-based and cost-effective practice. Completion of care guidelines have been found to decrease the incidence of patient disease complications, thereby alleviating unexpected exacerbations of illness that lead to increased patient visits and hospitalizations.

The process of co-management needs to be carefully examined within individual organizational institutions for successful implementation. Characteristics of effective co-management include effective communication, trust and respect, and a shared philosophy of care to ensure clinical alignment. These characteristics need to be supported by ensuring that both providers have access to each other’s patient care documentation; a mutually agreed up on mode of communication; and strategies to promote alignment of clinical management. Policies and an organizational culture that recognizes NPs as independent providers will be necessary to allocate equivalent support and resources that are needed to deliver optimal patient care. It has also been noted that over time, trust and respect between providers increases, and moreover, will be strengthened when providers are given enough time and space to co-manage through collaboration. Organizational policy should reflect these efforts and the provision of such resources will promote the success of interprofessional teams when providers from various disciplines co-manage the patient’s plan of care.

It is important to also recognize that NP-physician co-management holds potential in helping organizations adhere to changes in national policy. For example, as the U.S. shifts from volume-based to value-based payment (VBP) infrastructure, the strain to complete all recommended care guidelines is vital for an organization to be reimbursed for its patient care services. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) are increasingly shifting toward reimbursements for patient care that are based on the completion of disease-targeted outcomes and guidelines are required to maintain a high quality of care (Burwell, 2015). As previously mentioned, the ability of a single PCP to complete all recommended guidelines for each patient is often difficult and unrealistic when working as the sole PCP. This review demonstrates early evidence of the potential for NP-physician co-management to help alleviate this organizational strain.

In regards to research implications, a substantial amount of research is warranted to understand more about the NP-physician co-management delivery model. First, the current literature lacks a description of how NP-physician co-management is carried out, such as the delegation of tasks, communication between the NP and physician, or how they interact. It is also unclear if each discipline is willing to work within a co-management care delivery model. Research that is qualitative in nature is recommended to obtain descriptions of the process of existing NP-physician co-management care delivery, as well as, the PCP and/or patient perspective of this type of care delivery. This should include a closer look at what attributes strengthen or impede a successful co-management relationship between NPs and physicians so that health services researchers can continue to evaluate patient and practice outcomes for this care delivery model. Further, due to some of the identified limitations of the studies included in this review, future research should include studies that control for baseline blood pressure and lab values, as well as medications, thereby eliminating bias and potential confounders when investigating co-management effects. Finally, given that primary care is increasingly being delivered by teams with various types of PCPs, it is also recommended that future studies explore co-management care delivery by other types of PCPs, such as physician assistants.

In summary, as the NP workforce continues to increase and policymakers encourage the expansion of NP scope of practice, such as independent NP practice, the results of this review shed light on the potential benefit of NPs and physicians co-managing primary care patients together. More research is needed to determine the best way for organizations, managers, and researchers to successfully implement such a model. The authors of this review support the movement to continually expand the NP workforce in primary care given the emerging and promising evidence of NP-physician co-management to deliver high quality patient care.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding:

This study is funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) Comparative and Cost-Effectiveness Research Training for Nurse Scientists, T32 NR014205 (PI: Stone) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Nurse Faculty Scholars Program.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

None declared.

Contributor Information

Allison Andreno Norful, PhD Candidate-Center for Health Policy; Columbia University School of Nursing.

Kyleen Swords, DNP Candidate-Columbia University School of Nursing.

Mickaela Marichal, DNP Candidate-Columbia University School of Nursing.

Hwayoung Cho, PhD Candidate-Columbia University School of Nursing.

Lusine Poghosyan, Assistant Professor-Columbia University School of Nursing.

References

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Primary care for the 21st century: ensuring a quality, physician-led team for every patient. 2012 Retrieved October 25, 2014 from http://www.aafp.org/online/en/home/membership/initiatives/nps/patientcare.html.

- American Academy of Nurse Practitioners (AANP) NP fact sheet. 2015 Retrieved October 1, 2015 from http://www.aanp.org/all-about-nps/np-fact-sheet.

- American College of Physicians (ACP) Nurse practitioners in primary care: A policy monograph of the American College of Physicians. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association. Influenza and Pneumonial Vaccination in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(1):s111–s113. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.S111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach DI. Will the NP workforce grow in the future? New forecasts and implications for healthcare delivery. Medical Care. 2012;50(7):606–610. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318249d6e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Ghorob A, Willard-Grace R, Grumbach K. The 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care. Annals of Family Medicine. 2014;12(2):166–171. doi: 10.1370/afm.1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Pham HH. Primary care: current problems and proposed solutions. Health Affairs. 2010;29(5):799–805. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burwell SM. Setting value-based payment goals—HHS efforts to improve US health care. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(10):897–899. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt FW, Austrom MG, Damush TM, Perkins AJ, Hendrie HC. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer disease in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(18):2148–2157. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.18.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donelan K, DesRoches CM, Dittus RS, Buerhaus P. Perspectives of physicians and nurse practitioners on primary care practice. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368(20):1898–1906. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1212938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortinsky RH, Delaney C, Harel O, Pasquale K, Schjavland E, Lynch J, Crumb S. Results and lessons learned from a nurse practitioner-guided dementia care intervention for primary care patients and their family caregivers. Research in Gerontological Nursing. 2014;7(3):126–137. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20140113-01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz DA, Koretz BK, Bail JK, McCreath HE, Wenger NS, Roth CP, Reuben DB. Nurse practitioner comanagement for patients in an academic geriatric practice. American Journal of Managed Care. 2010;16(12):e343–355. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halcomb EJ, Davidson PM, Daly JP, Griffiths R, Yallop J, Tofler G. Nursing in Australian general practice: directions and perspectives. Australian Health Review. 2005;29(2):156–166. doi: 10.1071/ah050156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litaker D, Mion L, Planavsky L, Kippes C, Mehta N, Frolkis J. Physician - nurse practitioner teams in chronic disease management: the impact on costs, clinical effectiveness, and patients’ perception of care. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2003;17(3):223–237. doi: 10.1080/1356182031000122852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. The Lancet. 2006;367(9524):1747–1757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Misener R, Harbman P, Donald F, Reid K, Kilpatrick K, Carter N, Charbonneau-Smith R. Cost-effectiveness of nurse practitioners in primary and specialised ambulatory care: systematic review. BMJ Open. 2015;5(6):e007167. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitka M. Looming shortage of physicians raises concerns about access to care. JAMA. 2007;297(10):1045–1046. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.10.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009;62(10):1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray M, Davies M, Boushon B. Panel size: how many patients can one doctor manage? Fam Pract Manag. 2007;14(4):44–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohman-Strickland PA, Orzano AJ, Hudson SV, Solberg LI, DiCiccio-Bloom B, O’Malley D, Crabtree BF. Quality of diabetes care in family medicine practices: influence of nurse-practitioners and physician’s assistants. Annals of Family Medicine. 2008;6(1):14–22. doi: 10.1370/afm.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penning-van Beest FJ, Termorshuizen F, Goettsch WG, Klungel OH, Kastelein JJ, Herings RM. Adherence to evidence-based statin guidelines reduces the risk of hospitalizations for acute myocardial infarction by 40%: a cohort study. European heart journal. 2007;28(2):154–159. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuben DB, Ganz DA, Roth CP, McCreath HE, Ramirez KD, Wenger NS. Effect of nurse practitioner comanagement on the care of geriatric conditions. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2013;61(6):857–867. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanik-Hutt J, Newhouse RP, White KM, Johantgen M, Bass EB, Zangaro G, Heindel L. The quality and effectiveness of care provided by nurse practitioners. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 2013;9(8):492–500. e413. [Google Scholar]

- Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank quarterly. 2005;83(3):457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutsky BJ, Spence Laschinger H. Development and testing of a conceptual framework for interprofessional collaborative practice. Health and Interprofessional Practice. 2014;2(2):eP1066. doi: 10.7710/2159-1253.1066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SY, Green A. Projection of chronic illness prevalence and cost inflation. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Health; 2000. 2000. [Google Scholar]