Abstract

Impulsivity, a multifaceted behavioral hallmark of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), strongly influences addiction vulnerability and other psychiatric disorders that incur enormous medical and societal burdens yet the neurobiological underpinnings linking impulsivity to disease remain poorly understood. Here we report the critical role of ventral striatal cAMP-response element modulator (CREM) in mediating impulsivity relevant to drug abuse vulnerability. Using an ADHD rat model, we demonstrate that impulsive animals are neurochemically and behaviorally more sensitive to heroin and exhibit reduced Crem expression in the nucleus accumbens core. Virally increasing Crem levels decreased impulsive action, thus establishing a causal relationship. Genetic studies in seven independent human populations illustrate that a CREM promoter variant at rs12765063 is associated with impulsivity, hyperactivity and addiction-related phenotypes. We also reveal a role of Crem in regulating striatal structural plasticity. Together, these results highlight that ventral striatal CREM mediates impulsivity related to substance abuse and suggest that CREM and its regulated network may be promising therapeutic targets.

Impulsivity is a symptom that spans psychiatric diagnostic boundaries comprising risky behavior, unreflective decision making, premature actions and deficits in delaying gratification1. It is notably a core feature of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and highly comorbid with substance use disorders (SUDs)2–7. Multiple human and animal investigations show a strong relationship between pre-existing impulsivity traits and SUD vulnerability. Psychostimulants are the drug class mainly examined with impulsivity, but recent clinical evidence suggests that heroin-dependent individuals also exhibit greater impulsivity and sensation-seeking traits8–10 which is significant considering that opiates are the second most abused illicit drugs in the USA11.

Although the neurobiology relating impulsivity with SUD is unknown, frontostriatal and mesocorticolimbic circuits that mediate decision-making and motivation likely play critical roles12, 13. The nucleus accumbens (Acb) is an important neuroanatomical hub within these circuits given that the core (AcbC) and shell (AcbSh) subregions modulate different components of impulsivity, such as impulsive choice, reflecting cognitive impulsivity, and impulsive action, reflecting motor impulsivity and inhibitory control14–18. The molecular underpinnings of drug addiction vulnerability within specific Acb subregions relevant to distinct impulsive behavioral domains remain unknown.

Here, we used a multidisciplinary approach to identify neurobiological substrates of impulsivity associated with opiate abuse. We demonstrate that spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs), a common ADHD model, have greater behavioral and neurochemical sensitivity to heroin. Using this model revealed a critical role of the transcription factor Crem in the AcbC in mediating impulsive action with epigenetic and genetic factors contributing to its regulation. Studying multiple human cohorts, we showed associations between CREM polymorphism and impulsivity, hyperactivity, and substance abuse in individuals with ADHD and SUD. We identified a molecular network associated with Crem related to synaptic plasticity and directly demonstrated that Crem regulates dendritic morphology. Altogether, this translational study provides a novel molecular target for components of impulsivity trait important for substance abuse.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal models and behavioral tasks

Animals

Male SHRs and WKYs, obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Raleigh, NC), were housed in a humidity- and temperature-controlled environment on a reversed 12-hr light/dark cycle (lights off at 09:00) with ad libitum access to food and water. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. For surgical procedures, see Supplementary Information.

Behavioral tasks

Impulsivity was studied using a temporal discounting task known as intolerance-to-delay (ITD) during which animals selected either an immediate single-pellet or a delayed 5-pellet reward. Novelty-seeking and heroin-induced locomotor activity were assessed in open-field arenas. For self-administration (SA) experiments, rats were trained to intravenously self-administer heroin, then underwent extinction training and cue-induced reinstatement. For details, see Supplementary Information.

In vivo neurochemistry, molecular biology, and cell culture

Dopamine concentration after acute heroin injection was measured from AcbC of SHRs and WKYs using in vivo microdialysis and high-performance liquid chromatography. Gene expression was measured from Acb of SHRs and WKYs using RT-qPCR. Epigenetic modifications near Crem were assessed in Acb of SHRs and WKYs using either chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and qPCR, or bisulfite conversion and sequencing. Primary cortical and striatal neurons derived from Long-Evans embryos were co-cultured for dendritic neuromorphology. For details, see Supplementary Information.

Human genetic studies

Association studies were performed to understand the relationship between CREM and traits related to impulsivity. All participants provided informed consent and studies were conducted in accordance with institutional approval (Queens College, CUNY, for preschool and adolescent ADHD studies; Wayne State University for post mortem opiate use studies; Semmelweis University, Hungary, for post mortem heroin use studies; and Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, for cannabis dependence studies). For details and demographics, see Supplementary Information.

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as mean (± s.e.m.) unless otherwise indicated and statistical analyses, as detailed in Supplementary Information, were performed using SPSS (v22), GraphPad Prism (v6), and PLINK (v1.06)19. Sample sizes for animal studies were determined based on experience of effects typically encountered in behavioral and molecular studies while human studies were based on previously published datasets. For details, see Supplementary Information.

RESULTS

ADHD animal model characterized by enhanced impulsivity and heroin sensitivity

In order to better understand the relationship between behavioral traits and addiction vulnerability, we first characterized SHRs to discern different aspects of impulsivity relevant to human substance abuse. Since SHRs are genetically derived from Wistar-Kyoto rats (WKYs), these animals were used as controls. Animals performed a temporal discounting task (intolerance-to-delay, ITD) that measured choice between an immediate small reward (1 food pellet) and a delayed large reward (5 food pellets) (Supplementary Fig. 1). The delay length was gradually increased during the test phase and impulsive choice was reflected by relative preference for the immediate reward (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Both SHRs and WKYs decreased preference for the large reward as delay increased (F6,174=53.76, p<0.001). This relative shift in preference towards the smaller, immediate reward was, however, significantly faster in impulsive rats (F6,174=3.05, p=0.007) confirming that SHRs exhibit elevated impulsive choice (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 2a). Lever presses were also recorded during the delay period, after pressing L5 but before receiving food. Although intra-delay presses did not result in additional food-delivery, shifting responses to L1 during this period reflected impulsive action (Supplementary Fig. 1d). While both strains displayed more intra-delay L1 presses as the delay increased (F5,145=36.73, p<0.001), this increase was more pronounced in SHRs (F5,145=10.55, p<0.001), consistent with this strain’s elevated impulsive action (Fig. 1b). Since the delay period strictly followed L5 presses, not L1, perseveration on this lever during the delay was used to distinguish compulsivity from impulsive action. Thereby, intra-delay L5 presses also increased in both strains during the testing phase (F5,145=27.13, p<0.001) and, while there was a strain × time interaction (F5,145=2.83, p=0.02), post-hoc analysis did not reveal significant differences between strains during any session (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Similar pressing patterns were observed during the fixed time-out period—during which a cue signaled the unavailability of a reward—and responses on L1 were significantly different between SHRs and WKYs (F1,29=32.79, p<0.001, Supplementary Fig. 2c).

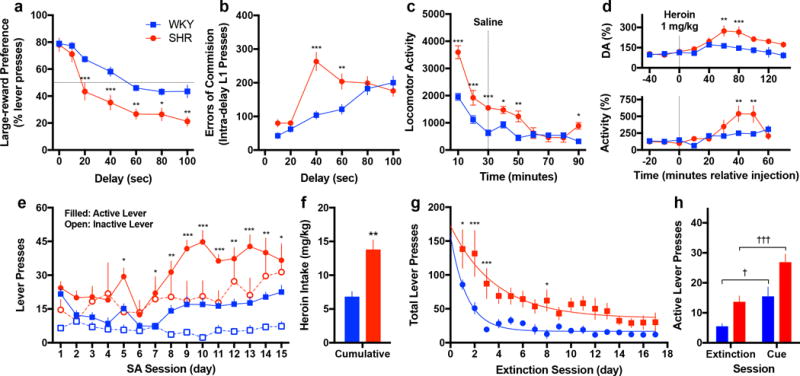

Figure 1. Increased heroin addiction risk in impulsive animals.

(a–c) Impulsive SHRs exhibit a greater preference for the immediate reward as a function of delay (a), commit more errors of commission during the delay period (b), and show increased novelty seeking in an open-field arena (c) (for ITD, n = 15 SHR and 16 WKY; for open-field, n = 8 per group). (d) After an acute, single-dose injection of heroin, SHRs exhibit elevated extracellular dopamine in the AcbC (upper panel) and increased locomotor activity (lower panel) (for microdialysis, n = 4 SHR and 6 WKY and shown relative baseline; for open-field, n = 7 per group and shown relative saline-treated animals from panel c). (e–h) Impulsive SHRs also exhibit elevated heroin self-administration (e) and cumulative intake (f), attenuated extinction (g), and enhanced reinstatement (h) (n = 5 SHR and 6 WKY). All data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 relative WKY; †P < 0.05, †††P < 0.001 relative extinction day; independent or paired t-tests with Holm-Šidák correction, see results text for ANOVA statistics.

In addition to these behavioral measures of impulsivity, SHRs exhibited increased hyperactivity during ITD (F1,29=49.22, p<0.001, Supplementary Fig. 2d) and increased novelty seeking when placed in a novel open-field arena (F1,14=22.10, p<0.001, Fig. 1c). Moreover, SHRs were more sensitive to heroin’s acute neurochemical and behavioral effect. While there was no baseline difference in extracellular dopamine levels in the AcbC between the two strains (t8=1.10, p=0.30), SHRs exhibited a more pronounced heroin-induced increase (F9,72=3.39, p=0.002, Fig. 1d, upper panel), consistent with their enhanced locomotor response (F8,96=6.18, p<0.001, Fig. 1d, lower panel).

We next directly tested whether impulsive SHRs were more vulnerable to heroin addiction using a drug self-administration (SA) task that models different components of the abuse cycle. While lever pressing did not initially differ between the strains, SHRs pressed more on both active (F1,9=18.62, p=0.002. Fig. 1e) and inactive levers (F1,9=5.11, p=0.05, Fig. 1e) during the maintenance phase, and therefore cumulatively consumed more heroin than WKYs (t9=4.31, p=0.002, Fig. 1f). Despite their clear preference for the active lever, SHRs showed diminished motor inhibition evident by greater inactive lever pressing relative WKYs, which is in line with their elevated impulsive action as measured in the ITD task. While differences in inactive lever pressing could represent the strains’ baseline differences in locomotor activity, this does not fully explain the SA data since there was no correlation between inactive lever responses and general locomotion (Supplementary Fig. 3).

After stable maintenance, animals underwent an extinction phase at which time responses on the previously reinforced lever resulted in saline delivery, not heroin. As expected, lever pressing decreased over time in both strains (F16,128=10.27, p<0.001, Fig. 1g), yet as evident by non-linear regression, SHRs extinguished at a slower rate (k parameter: t32=2.84, p=0.008) and to a lesser extent (plateau parameter: t32=3.41, p=0.002). Following extinction, reinstatement liability was determined by exposing the animals to a non-extinguished cue previously associated with heroin delivery. The drug-associated cue promoted heroin seeking behavior in both strains (F1,8=37.61, p<0.001), but SHRs exhibited enhanced heroin seeking with a larger number of active lever presses than WKY (t8=2.64, p=0.03, Fig. 1h). Overall, these results demonstrate that SHRs have greater dopamine sensitivity to heroin, maintain higher levels of heroin intake, exhibit decreased capacity to extinguish their drug intake, and have a greater tendency for relapse, all supporting the hypothesis of enhanced drug addiction sensitivity associated with the impulsive phenotype.

Reduced AcbC Crem expression mediates impulsive action

Given the central role of the AcbC in behaviors related to impulsivity and drug addiction20, 21, our next goal was to identify molecular underpinnings of SHRs’ impulsive predisposition. Of the genes related to synaptic plasticity and neurotransmission included in our expression panel, the transcription factor Crem showed the greatest difference (t10=3.62, p=0.005, Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table 1). The decrease, specific to the AcbC (Fig. 2a inset), was verified using an independent qRT-PCR assay (t10=3.31, p=0.008) and reproduced in a separate cohort of animals (t15=2.22, p=0.042). Interestingly, acute heroin (1 mg/kg, ip) increased Crem mRNA expression in the AcbC of SHRs (t10=8.54, p<0.001) but not WKYs (t9=0.172, p>0.05), while Crem was equally induced in the AcbSh of both strains (Fig. 2b).

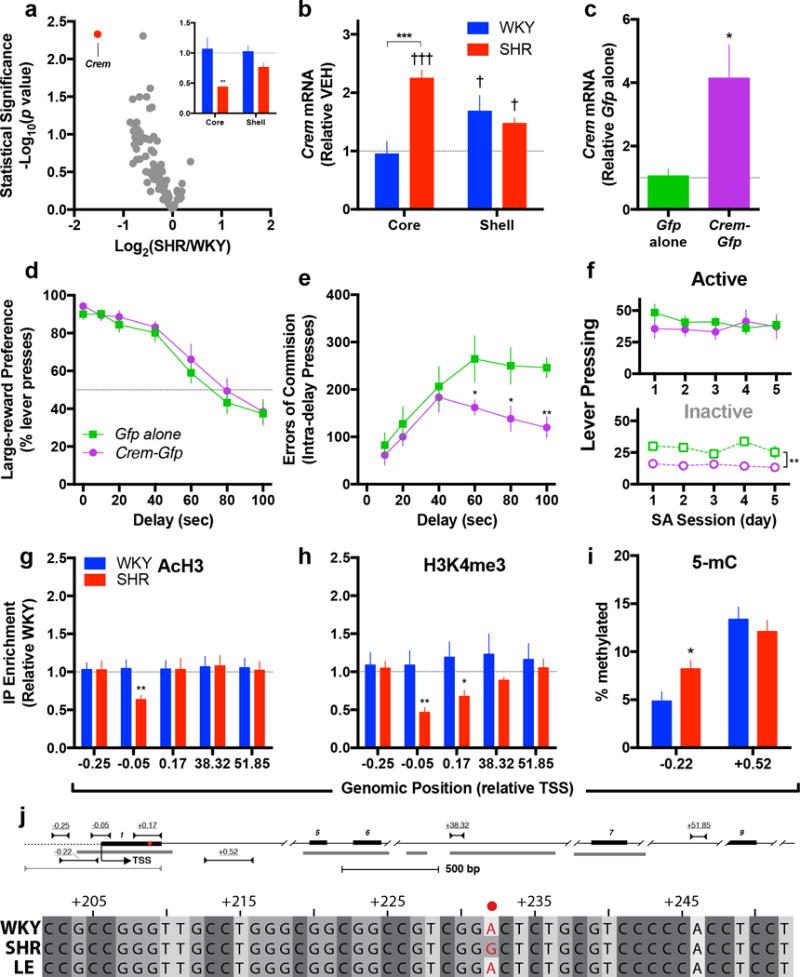

Figure 2. Crem in the AcbC alters impulsive action and associates with genetic and epigenetic alterations in impulsive animals.

(a) Crem was reduced in the Acb of drug-naïve SHRs, specifically in the AcbC but not AcbSh (inset) (for array, n = 6 per group; for single-assay validation, n = 6 per group for AcbC, 5 SHR and 6 WKY for AcbSh). (b) Acute heroin induced Crem in the AcbC of SHRs but not WKYs, while in the AcbSh, heroin produced similar increases in both strains (n = 6 SHR and 5 WKY and shown relative saline-treated animals in panel a). (c) To study the causal contribution of Crem to impulsivity, HSV-Crem-Gfp was infused into the AcbC of SHRs resulting in over-expression (n = 4 Gfp and 5 Crem-Gfp, 2 independent experiments). (d–f) While over-expression did not impact preference for the large-reward (d), it decreased errors of commission during ITD (e) and inactive lever pressing during heroin self-administration (f) (for ITD, n = 5 Gfp and 7 Crem-Gfp; for SA, n = Gfp and 6 Crem-Gfp). (g–i) In the AcbC of SHRs, the permissive histone marks AcH3 (g) and H3K4me3 (h) were depleted near the Crem TSS, while DNA methylation was elevated upstream within the promoter (i) (n = 8 per group for ChIP, 8–10 per group for methylation). (j) Schematic of the rat Crem illustrating exons (numbered black bars), conserved regions (gray bars), and PCR primers used for ChIP-qPCR (top), bisfulfite sequencing (middle) and Sanger sequencing (bottom), all numbered relative the transcriptional start site (TSS). Single-nucleotide polymorphism within the first non-coding exon of rat Crem (indicated by •). Sequencing results from outbred Long Evans (LE) strain shown for reference. All data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 relative WKY or Gfp alone; †††P < 0.001 relative vehicle treatment (shown as horizontal line); independent t-tests with Holm-Šidák correction (for behavior) and Fisher’s LSD (for qCPR), see results text for ANOVA statistics.

We next over-expressed Crem in the AcbC of SHRs and evaluated ITD and heroin SA to determine this gene’s potential causal relationship to impulsivity and related behavior. For ITD, HSV-Crem-Gfp or HSV-Gfp (Gfp alone) was bilaterally infused into the AcbC one day before the start of testing (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Compared to control, HSV-Crem-Gfp infusion elevated Crem expression (t7=2.56, p=0.038, Fig. 2c) but did not alter choice for large reward (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 4b) or locomotor activity (Supplementary Fig. 4e). Instead, these animals exhibited lower intra-delay L1 responses as the delay increased (F5,50=2.40, p=0.05, Fig. 2e) while neither intra-delay L5 pressing (F5,50=2.32, p=0.06, Supplementary Fig. 4c) nor L1 pressing during the time-out period (F1,10=0.52, p=0.49, Supplementary Fig. 4d) differed between groups. These data show that AcbC Crem specifically reduced L1 responses during the delay period and suggest an association with impulsive action, not impulsive choice, compulsivity or general hyperactivity. For heroin SA, HSV-Crem-Gfp or HSV-Gfp was bilaterally infused into the AcbC of a different cohort of animals the day before the first session. Over-expression did not impact responses on the heroin-associated active lever but significantly decreased inactive lever pressing (F1,9=13.50, p=0.005, Fig. 2f). These data indicate that AcbC Crem does not affect heroin reinforcement per se but decreases impulsive action in the context of a reward-related behavior.

Epigenetic and genetic signature of Acb Crem differs in impulsive animals

Epigenetic factors tightly regulate gene expression and thereby could contribute to the subregionally specific deficit in Crem observed in SHRs. To explore this hypothesis, we studied histone post-translational modifications which play well-documented roles in transcriptional regulation. Chromatin from the AcbC and AcbSh were immunoprecipitated with antibodies specific for pan-acetylated histone H3 (H3Ac) and trimethylated histone 3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3), both typically markers of transcriptional activation, and dimethylated histone 3 lysine 9 (H3K9me2), a repressive marker. The profile of H3Ac revealed lower enrichment of this mark close to the transcriptional start site (TSS) in the AcbC of SHRs (t13=3.05, p=0.009, Fig. 2g and Supplementary Fig. 5a), but not the AcbSh (t14=0.72, p>0.05, Supplementary Fig. 5d). Similarly, lower H3K4me3 enrichment was observed in the AcbC of SHRs around the TSS (−0.05 kb relative TSS, t13=2.98, p=0.01) and in a downstream region (+0.17 kb relative TSS, t13=2.49, p=0.02, Fig. 2h and Supplementary Fig. 5b,e). Enrichment of H3K9me2 showed no difference between the rat strains at any examined loci except +0.17 kb downstream the TSS in the AcbSh (t14=3.31, p=0.005, Supplementary Fig. 5c,f). These region-specific epigenetic changes are in line with the transcriptional differences observed between the strains. Concomitant with the histone post-translation modifications, SHRs exhibited greater cytosine methylation immediately upstream the TSS within a conserved CpG island (t16=2.60, p=0.019), but not within the gene-body (t18=0.74, p=0.47, Fig. 2i).

Since DNA sequence may account for differences in expression, we sequenced the region of Crem with differences in histone modification and identified a non-coding SNP in the first exon unique to SHRs (Fig. 2j). Altogether, these data suggest that SHRs exhibit distinct epigenetic modifications in the AcbC as well as a unique genetic variant within the Crem gene that provides a potential bridge for human phenotypes.

Genetic variants of CREM associate with impulsivity and substance use in human populations

To determine whether CREM relates to impulsivity and addiction vulnerability in humans, we studied CREM genotype in relation to behavior guided by the animal findings. We performed a set of independent, hypothesis-driven association studies focused on a variant within the CREM gene (rs12765063) that was similarly positioned within the CREM locus when compared to the rodent polymorphism (Fig. 2j). This variant was within a conserved region of the promoter, in strong linkage disequilibrium with the surrounding region, and enriched with H3K27Ac and H3K4me3 in the striatum22, all suggesting the presence of adjacent regulatory features (Supplementary Fig. 7).

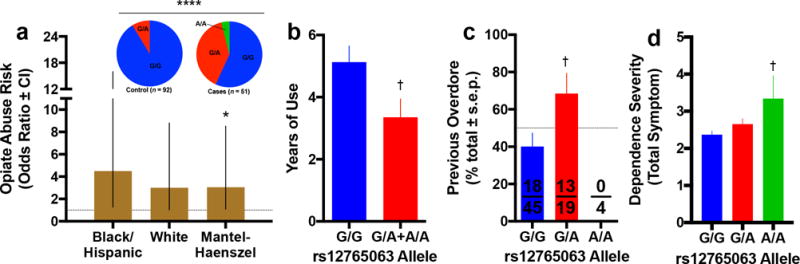

We first investigated the relationship between opiate abuse and striatal CREM by studying two independent postmortem opiate abuse populations. In the first population, composed of an ethnically heterogeneous US population23, 24, rs12765063 was associated with elevated risk of opiate abuse (Χ2=24.30, p<0.0001, Fig. 3a inset). To eliminate the possibility that this pronounced effect was due to ancestral differences between the two groups, we separately analyzed on the basis of race and still detected significant associations (Mantel–Haenszel Test, Χ2=5.03, p=0.025, Fig. 3a). In an independent, ethnically homogenous European population25, rs12765063 associated with measures of abuse severity, namely years of use preceding lethal intoxication (t43=2.16, p=0.036, Fig. 3b) and history of previous overdose (Χ2=4.32, p=0.038, Fig. 3c), but not heroin abuse (Χ2=0.31, p=0.58). These data suggest that CREM associates with hazardous patterns of opioid use and a more rapid progression to lethal intoxication. In a large COGA dataset26 for which use of other substances was measured, rs12765063 significantly associated with DSM-IV alcohol dependence symptom count (β=0.063, p=0.002), and total symptom count for alcohol, marijuana, cocaine and opiate dependence (β=0.062, p=0.04, Fig. 3d). These observations suggest that CREM genotype broadly influences risk for drug dependence, rather than being specific for opiate abuse, and laid the foundation for our follow-up studies focused on ADHD and addiction vulnerability.

Figure 3. Genetic variation in CREM associates with substance use.

(a) In a post-mortem population composed of individuals with opiate abuse, the rs12765063 variant associated with increased risk of opiate abuse even after stratifying on the basis of ethnicity. (b) In our well-curated postmortem brain collection composed of ethnically homogenous heroin abusers, this variant associated with shorter duration of drug use, which, given the fact that brains were collected at death due to opiate overdose, suggests that individuals with the A-allele more rapidly progressed to lethal intoxication. (c) This is consistent with the finding that A-allele carriers were also more likely to experience a previous, albeit non-lethal overdose. (d) The additive genotypic effect of the A-allele on higher total number of symptoms for any drug dependence can clearly be seen. Homozygotes for the G/G genotype had an average 2.38±0.08 symptoms while homozygotes for the A/A genotype had an average of 3.36±0.61 symptoms. All data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. unless otherwise indicated on y axis. For sample sizes, see Supplementary Table 4. *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001 relative control participants; †P < 0.05, relative G/G genotype; independent t-tests with Holm-Šidák correction (versus control participants) or Fisher’s LSD (versus G/G), see results text for linear and non-linear regression.

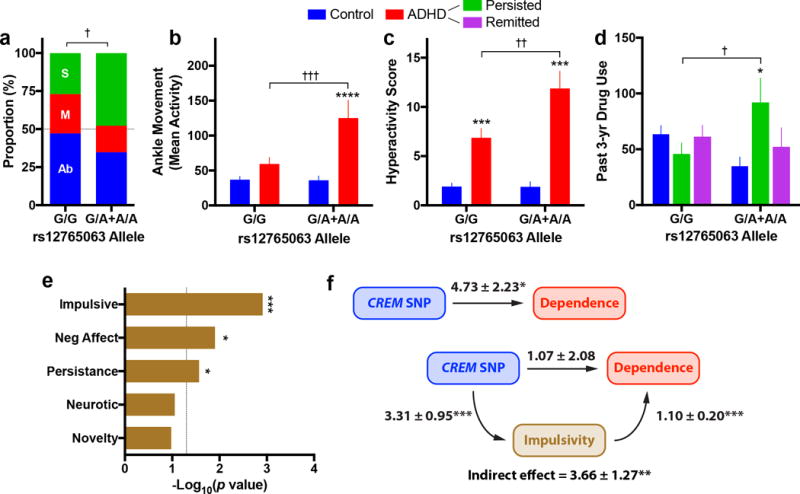

To gain insights into the relationship between impulsivity and CREM as relevant to addiction vulnerability, we examined three independent, longitudinal ADHD populations, each with age-matched controls. First, in preschool-aged children both with and without diagnosed ADHD27, rs12765063 associated with impulsive behavioral traits, namely distractibility (β=1.14, t127=2.54, p=0.01), engaging in dangerous activities (β=1.20, t127=2.41, p=0.02), and failing to listen to instruction (β=1.13, t127=2.32, p=0.02, Fig. 4a). In the second population composed of adolescents (~18 years-old) with ADHD studied since ~9 years-old28, rs12765063 strongly associated with measures of hyperactivity, namely ankle movement during neuropsychological testing (β=53.41, t127=2.59, p=0.011, Fig. 4b) and self-reported hyperactivity (β=4.26, t138=2.29, p=0.023, Fig. 4c). In this adolescent population, use of alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana and non-prescribed psychostimulants were measured revealing a significant ADHD × rs12765063 interaction (F1,138=5.35, p=0.02, Supplementary Fig. 8a). In more detail, drug use was considerably greater in ADHD subjects with the A-allele compared to controls with the same allele (t138=2.15, p=0.03). Since ADHD severity may change over time, subjects were stratified based on the presence or absence of ADHD symptoms at follow-up which again revealed a strong interaction between the CREM polymorphism and ADHD persistence (F2,136=4.35, p=0.02, Fig. 4d). Specifically, past drug use was significantly elevated in A-allele carriers with persistent symptomology when compared to controls (t136=2.61, p=0.02), but there was no difference between those in remission and controls (t136=0.69, p=0.49). Similar interactions were observed in a larger independent population of 1054 adolescents from IMAGEN29. After correcting for gender, age and ethnicity, there were significant ADHD × rs12765063 interactions with respect to the number of individuals reporting any lifetime use (β=0.93, Χ2=4.57, p=0.03, Supplementary Fig. 8b) and the amount of use by those reporting any use (F1,361=3.96, p=0.05, Supplementary Fig. 8c).

Figure 4. Genetic variation in CREM associates with impulsivity in the context of substance abuse.

(a) In a mixed cohort of preschool-aged children (3–5 years-old) with and without ADHD, CREM rs12765063 genetic variation associated with the proportion of individuals engaging in dangerous activities (Ab = absent, M = mild, S = severe). (b–c) This polymorphism associated with ankle movement (b) and self-reported DSM hyperactivity/impulsivity score (c). (d) Stratifying this population based on ADHD status at follow-up, the genetic association between CREM and reported use was almost exclusively driven by participants with persistent ADHD, not remitters. (e) In an adult population composed of cannabis dependent and non-dependent individuals, this genetic variant strongly associated with impulsivity and persistence, as well as negative affect. (f) Variation in impulsivity significantly mediated the association between CREM genotype and substance dependence severity as measured by cannabis consumption (values adjacent to arrows reflect regression coefficient ± standard error). All data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. unless otherwise indicated. For sample sizes, see Supplementary Table 4. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 relative control participants; †P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01 relative G/G genotype; independent t-tests with Holm-Šidák correction (versus control participants) or Fisher’s LSD (versus G/G), see results text for linear and non-linear regression.

We next leveraged data from a published study in which neuropsychological and behavioral measures were collected in adult drug (cannabis) dependent and non-dependent subjects30. In more details, rs12765063 significantly associated with increased impulsivity (β=3.21, t97=3.33, p=0.001) and decreased persistence (β=−12.12, t97=−2.25, p=0.027, Fig. 4e), with the association with impulsivity particularly strong in dependent individuals (β=3.71, t48=3.46, p=0.001, Supplementary Fig. 9a). Based on statistical mediation modeling, impulsivity mediated the association between CREM and dependence severity (PM=77%, Z=2.88, p=0.004, Fig. 4f, Supplementary Fig. 9b) even after incorporating self-reported race, gender and age as covariates (PM=63%, Z=2.72, p=0.007). No other trait except negative affect (β=3.63, t97=2.55, p=0.013) associated with this polymorphism. Overall, these findings support a genotype-phenotype association between CREM and impulsivity in the genetic link to addiction vulnerability.

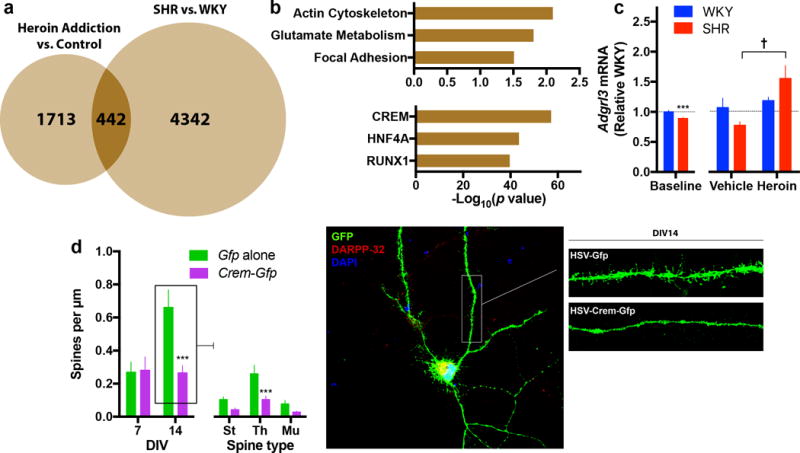

CREM regulation relates to neuroplasticity and dendritic spine morphology

To determine neuronal networks related to both impulsivity and heroin abuse, we compared differentially expressed genes derived from two ventral striatal microarrays— human heroin abusers versus matched controls and SHRs versus WKYs. While only 6.8% of the differentially expressed genes overlapped (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Table 2), not surprising given the clear differences in phenotype, the 442 shared genes were disproportionately targets of CREM and regulators of neuroplasticity related to actin cytoskeleton and focal adhesion (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Table 2). Intriguingly, this analysis highlighted adhesion-like G-protein-coupled receptor-3 (Adgrl3), an adhesion G-protein coupled receptor highly expressed in the striatum and implicated with ADHD31. Similar to Crem, SHRs exhibited significantly reduced AcbC Adgrl3 at baseline (t18=3.63, p=0.002, Fig. 5c), but were more sensitive to heroin’s acute effect (F1,19=5.31, p=0.033, Fig. 5c).

Figure 5. Impulsivity and heroin abuse share a common ventral striatal gene expression network that relates to CREM and neuroplasticity.

(a,b) To focus on networks related to both impulsivity and heroin abuse, we compared differentially expressed genes derived from two datasets. While there was only a modest overlap between heroin and SHR altered genes (a), the shared genes are disproportionately regulators of neuroplasticity (b, upper panel) and targets of Crem (b, lower panel). (c) Of these common genes, Adgrl3—a gene previously associated with ADHD—is differentially regulated in the AcbC of SHRs at baseline and after acute heroin exposure (n = 10 per group for baseline study, n = 6 SHR and 5–6 WKY for acute heroin study). (d) Primary striatal neurons (co-cultured with cortical neurons) over-expressing Crem for two days in vitro exhibited significantly less dendritic spines at DIV14 (St = Stubby, Th = Thin, Mu = Mushroom) (n = 11 cells per group from 2–3 independent experiments). All data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. unless otherwise indicated on x axis. ***P < 0.001 relative WKY or Gfp alone; †P < 0.05 relative vehicle; independent t-tests with Holm-Šidák correction, see results text for ANOVA statistics.

To explore the functional relationship between Crem and neuroplasticity identified in our network analysis, Crem was over-expressed in primary striatal neurons and structural neuromorphology was assessed. Neurons over-expressing Crem showed a profound attenuation in the normal spine developmental observed between 7 and 14 days in vitro (DIV). Crem over-expressing medium spiny neurons (marked by DARPP-32 immunoreactivity) exhibited significantly less total dendritic spines at DIV14 when compared to controls (F1,16=14.07, p=0.002, Fig. 5d), yet there was no difference at DIV7 (F1,13=0.04, p=0.85, Fig. 5d). This effect was most pronounced for thin spines that, given their more plastic and dynamic nature, were more abundant in developing neurons (Fig. 5d). These data suggest that Crem is a key regulator of spine morphology and development in striatal medium spiny neurons.

DISCUSSION

Our translational study provides direct neurobiological evidence for a causal relationship between the transcription factor Crem in the AcbC and motor impulsivity relevant to ADHD and SUD. Studying a genetically homogeneous inbred animal model and various human cohorts, we demonstrate that (i) impulsivity was associated with vulnerability to heroin abuse and reduced AcbC Crem expression, (ii) AcbC Crem specifically mediated impulsive action, and (iii) striatal Crem regulated spine morphology and neuroplasticity. While Crem expression in the AcbC was not a sufficient regulator of opiate reward sensitivity, it may contribute to factors related to severity and predisposition given that impulsivity mediated the genetic association between CREM and substance use. The fact that CREM genotype was not specific to one drug type suggests it relates to more general aspects of addiction vulnerability.

In contrast to CREB—a prominently studied member of CRE-binding transcription factors32—few neurobiological investigations have focused on CREM. This paucity may be partly due to the relatively lower and more restricted abundance of CREM in the brain and the complexity of CREM isoforms for which activator or repressor activities are not fully understood33, 34. Despite the strong sequence homology, Creb1 was not significantly altered in the AcbC of SHRs (Supplementary Table 1). Our findings demonstrate a reproducible genetic association between CREM genotype and hyperactivity in humans, in line with some locomotor patterns observed in knock-out mice35. While our animal studies demonstrated that Crem in the AcbC—the motor component of the ventral striatum—specifically mediates impulsive action, not general activity or impulsive choice, it is possible that CREM expression in other striatal subregions contributes to different features of impulsivity. Moreover, it will be important to assess the impact of long-term perturbation of Crem on behavior using viral vectors with persistent expression.

The initial identification of CREM based on our animal studies was supported by an independent bioinformatic evaluation of overlapping genes which revealed that the most significant network shared between impulsivity and heroin abuse related to CREM. Intriguingly, the results of this approach were validated by the presence of ADGRL3, previously known as Latrophilin-3 (LPHN3), which has recently been strongly implicated in ADHD31, 36. ADGRL3 is thought to transynaptically regulate excitatory synapses37 and the SHRs’ reduced AcbC Adgrl3 expression is consistent with the finding that decreased Lphn3 activity elicits ADHD-like behavior38. Dysregulated actin cytoskeleton, a process tightly coupled to dendritic spine morphology, was also identified in our network analysis. Since the role of CREM in striatal cytoarchitecture was not previously recognized in studies of addiction, our finding that Crem directly regulates dendritic spine morphology in medium spiny neurons opens new avenues of research.

To our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating a role of Crem in mediating impulsive behavior. While altering Crem expression in the AcbC on its own was not sufficient to influence heroin intake or relapse potential, it may be an important component of the neural system underlying addiction vulnerability via impulsivity. Overall, the current translational approach brings attention to CREM in the AcbC as a regulator of impulsive action and therefore may help to identify novel pharmacotherapeutic targets in the treatment of ADHD and SUDs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) grants R01-DA015446 (YLH), R01-DA030359 (YLH), R01-DA006470 (MJB), F30-DA038954 (MLM), F31-DA031559 (CVM) and T32-DA007135 (NAW); the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grants R01-MH068286 (JMH) and R01-MH060698 (JMH); the National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant T32-GM007280 (MLM). The Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA) is supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) grant U10-AA008401. We thank Nayana Patel, James Sperry and Joseph A. Landry for technical assistance; Dr. Rachael L. Neve for generating the viral particles; Dr. Thomas A. Green for providing Crem plasmid.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors do not declare any conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

YLH, YR and MLM designed experiments. MLM, YR, HS, NAW, GE and CT performed experiments and/or analyzed data. JH, AM, MJB, BC, HG, GS and IMAGEN Consortium provided access to materials and resources. MK performed analyses in the COGA dataset. MLM, HS and YLH wrote the paper. All coauthors reviewed the manuscript and provided comments.

Supplementary information is available at Molecular Psychiatry’s website.

References

- 1.Daruna JH, Barnes PA. A neurodevelopmental view of impulsivity. In: McCown WG, Johnson J, Shure MB, editors. The Impulsive Client: Theory, Research, and Treatment. American Psychological Association; Washing DC, US: 1993. pp. 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nigg JT, Wong MM, Martel MM, Jester JM, Puttler LI, Glass JM, et al. Poor response inhibition as a predictor of problem drinking and illicit drug use in adolescents at risk for alcoholism and other substance use disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(4):468–475. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000199028.76452.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Mezzich A, Cornelius JR, Pajer K, Vanyukov M, et al. Neurobehavioral disinhibition in childhood predicts early age at onset of substance use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(6):1078–1085. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belin D, Mar AC, Dalley JW, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. High impulsivity predicts the switch to compulsive cocaine-taking. Science. 2008;320(5881):1352–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.1158136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalley JW, Fryer TD, Brichard L, Robinson ES, Theobald DE, Laane K, et al. Nucleus accumbens D2/3 receptors predict trait impulsivity and cocaine reinforcement. Science. 2007;315(5816):1267–1270. doi: 10.1126/science.1137073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diergaarde L, Pattij T, Poortvliet I, Hogenboom F, de Vries W, Schoffelmeer AN, et al. Impulsive choice and impulsive action predict vulnerability to distinct stages of nicotine seeking in rats. Biological psychiatry. 2008;63(3):301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perry JL, Nelson SE, Carroll ME. Impulsive choice as a predictor of acquisition of IV cocaine self- administration and reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in male and female rats. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;16(2):165–177. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng H, Lee TM, Waters JH, So KF, Sham PC, Schottenfeld RS, et al. Impulsivity, cognitive function, and their relationship in heroin-dependent individuals. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2013;35(9):897–905. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2013.828022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peles E, Schreiber S, Sutzman A, Adelson M. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder among former heroin addicts currently in methadone maintenance treatment. Psychopathology. 2012;45(5):327–333. doi: 10.1159/000336219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dissabandara LO, Loxton NJ, Dias SR, Dodd PR, Daglish M, Stadlin A. Dependent heroin use and associated risky behaviour: the role of rash impulsiveness and reward sensitivity. Addictive behaviors. 2014;39(1):71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.SAMHSA. Behavioral health trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2015. (NSDUH Series H-50, HHS Publication No. SMA 15-4927). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalley JW, Mar AC, Economidou D, Robbins TW. Neurobehavioral mechanisms of impulsivity: fronto-striatal systems and functional neurochemistry. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 2008;90(2):250–260. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bechara A, Van Der Linden M. Decision-making and impulse control after frontal lobe injuries. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18(6):734–739. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000194141.56429.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cardinal RN, Pennicott DR, Sugathapala CL, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Impulsive choice induced in rats by lesions of the nucleus accumbens core. Science. 2001;292(5526):2499–2501. doi: 10.1126/science.1060818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jentsch JD, Ashenhurst JR, Cervantes MC, Groman SM, James AS, Pennington ZT. Dissecting impulsivity and its relationships to drug addictions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1327:1–26. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.da Costa Araujo S, Body S, Hampson CL, Langley RW, Deakin JF, Anderson IM, et al. Effects of lesions of the nucleus accumbens core on inter-temporal choice: further observations with an adjusting-delay procedure. Behavioural brain research. 2009;202(2):272–277. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pothuizen HH, Jongen-Relo AL, Feldon J, Yee BK. Double dissociation of the effects of selective nucleus accumbens core and shell lesions on impulsive-choice behaviour and salience learning in rats. The European journal of neuroscience. 2005;22(10):2605–2616. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sesia T, Temel Y, Lim LW, Blokland A, Steinbusch HW, Visser-Vandewalle V. Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens core and shell: opposite effects on impulsive action. Exp Neurol. 2008;214(1):135–139. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koob GF. Neurobiological substrates for the dark side of compulsivity in addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Suppl 1):18–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stefanik MT, Moussawi K, Kupchik YM, Smith KC, Miller RL, Huff ML, et al. Optogenetic inhibition of cocaine seeking in rats. Addiction biology. 2013;18(1):50–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00479.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ward LD, Kellis M. HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:D930–934. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr917. Database issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albertson DN, Schmidt CJ, Kapatos G, Bannon MJ. Distinctive profiles of gene expression in the human nucleus accumbens associated with cocaine and heroin abuse. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(10):2304–2312. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobs MM, Okvist A, Horvath M, Keller E, Bannon MJ, Morgello S, et al. Dopamine receptor D1 and postsynaptic density gene variants associate with opiate abuse and striatal expression levels. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(11):1205–1210. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drakenberg K, Nikoshkov A, Horvath MC, Fagergren P, Gharibyan A, Saarelainen K, et al. Mu opioid receptor A118G polymorphism in association with striatal opioid neuropeptide gene expression in heroin abusers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(20):7883–7888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600871103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edenberg HJ, Bierut LJ, Boyce P, Cao M, Cawley S, Chiles R, et al. Description of the data from the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA) and single-nucleotide polymorphism genotyping for Genetic Analysis Workshop 14. BMC Genet. 2005;6(Suppl 1):S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-6-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajendran K, Rindskopf D, O’Neill S, Marks DJ, Nomura Y, Halperin JM. Neuropsychological functioning and severity of ADHD in early childhood: a four-year cross-lagged study. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122(4):1179–1188. doi: 10.1037/a0034237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trampush JW, Jacobs MM, Hurd YL, Newcorn JH, Halperin JM. Moderator effects of working memory on the stability of ADHD symptoms by dopamine receptor gene polymorphisms during development. Dev Sci. 2014;17(4):584–595. doi: 10.1111/desc.12131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schumann G, Loth E, Banaschewski T, Barbot A, Barker G, Buchel C, et al. The IMAGEN study: reinforcement-related behaviour in normal brain function and psychopathology. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(12):1128–1139. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jutras-Aswad D, Jacobs MM, Yiannoulos G, Roussos P, Bitsios P, Nomura Y, et al. Cannabis-dependence risk relates to synergism between neuroticism and proenkephalin SNPs associated with amygdala gene expression: case-control study. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arcos-Burgos M, Jain M, Acosta MT, Shively S, Stanescu H, Wallis D, et al. A common variant of the latrophilin 3 gene, LPHN3, confers susceptibility to ADHD and predicts effectiveness of stimulant medication. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(11):1053–1066. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carlezon WA, Jr, Duman RS, Nestler EJ. The many faces of CREB. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28(8):436–445. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laoide BM, Foulkes NS, Schlotter F, Sassone-Corsi P. The functional versatility of CREM is determined by its modular structure. EMBO J. 1993;12(3):1179–1191. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05759.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rauen T, Hedrich CM, Tenbrock K, Tsokos GC. cAMP responsive element modulator: a critical regulator of cytokine production. Trends Mol Med. 2013;19(4):262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maldonado R, Smadja C, Mazzucchelli C, Sassone-Corsi P. Altered emotional and locomotor responses in mice deficient in the transcription factor CREM. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(24):14094–14099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wallis D, Hill DS, Mendez IA, Abbott LC, Finnell RH, Wellman PJ, et al. Initial characterization of mice null for Lphn3, a gene implicated in ADHD and addiction. Brain research. 2012;1463:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ranaivoson FM, Liu Q, Martini F, Bergami F, von Daake S, Li S, et al. Structural and Mechanistic Insights into the Latrophilin3-FLRT3 Complex that Mediates Glutamatergic Synapse Development. Structure. 2015;23(9):1665–1677. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lange M, Norton W, Coolen M, Chaminade M, Merker S, Proft F, et al. The ADHD-susceptibility gene lphn3.1 modulates dopaminergic neuron formation and locomotor activity during zebrafish development. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(9):946–954. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.