Abstract

Little is known about how adolescents cope with minority stressors related to sexual orientation. This study examined 245 lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) young adult’s (ages 21-25) retrospective reports of coping in response to LGB minority stress during adolescence (ages 13-19) to test the reliability and validity of a measure of minority stress coping. Further, the study examined associations between LGB minority stress coping and young adult psychosocial adjustment and high school attainment. Validation and reliability was found for three minority stress coping strategies: LGB-specific strategies (e.g., involvement with LGBT organizations), alternative-seeking strategies (e.g., finding new friends), and cognitive strategies (e.g., imagining a better future). LGB-specific strategies were associated with better psychosocial adjustment and greater likelihood of high school attainment in young adulthood, while alternative-seeking and cognitive-based strategies were associated with poorer adjustment and less likelihood of high school attainment.

Keywords: Sexual orientation, coping, minority stress, psychosocial adjustment, educational attainment

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) adolescents are more likely compared to their heterosexual peers to report compromised psychosocial well-being (for review, see Russell & Fish, 2016). For example, LGB adolescents are at increased risk for self-reported depressive symptoms (Marshal et al., 2011), low self-esteem (Ziyadeh et al., 2007), and lower levels of life satisfaction (Træen, Martinussen, Vittersø, & Saini, 2009). Recent longitudinal research also documents disparities in educational attainment by sexual orientation, such that individuals with same-sex attractions during adolescence attained less education compared to their opposite-sex attracted peers in young adulthood (Walsemann, Lindley, Gentile, & Welihindha, 2013). Minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003) suggests that mental health disparities are the result of LGB individuals’ marginalized position in society. According to this theory, proximal (e.g., internalized homonegativity) and distal minority stressors (e.g., experience of interpersonal homophobia) contribute to compromised mental health outcomes for LGB populations. Indeed, research suggests that encountered LGB-specific minority stressors (e.g., sexual orientation-based harassment in schools; Russell, Sinclair, Poteat, & Koenig, 2012) account for psychosocial disparities over and above more generalized stressors. These LGB-specific minority stressors occur in a broad range of ecological contexts, including, but not limited to, families (e.g., Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009) and schools (Russell et al., 2012).

Meyer’s (2003) minority stress model is a useful framework to understand the associations among victimization, rejection, and well-being for LGB individuals. The main tenet of Meyer’s model is that both internalized homonegativity (i.e., a proximal stressor) and heterosexist or homonegative experiences (e.g., actual or anticipated interpersonal victimization or rejection based on LGB status; societal-level discrimination; distal stressors) contribute to health disparities and greater behavioral risk outcomes for LGB individuals. Importantly, Meyer hypothesized that coping strategies and social support can buffer the associations between minority stress and outcomes. For the purposes of this study, coping is defined as the “efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person” (Folkman, Lazarus, Gruen, & DeLongis, 1986, p. 993). Thus, knowledge and awareness of specific coping strategies and support services used by marginalized populations is important for informing preventative interventions, policies, and future research. What remains unclear, however, is how LGB young people cope with the minority stressors they encounter that they attribute to their sexual orientation.

Few studies have empirically investigated coping among LGB adolescents (e.g., Craig, 2013; Goldbach & Gibbs, 2015; Kuper, Coleman, & Mustanski, 2013; Lock & Steiner, 1999). Importantly, given that the minority stress theoretical perspective was not published until 2003, Lock and Steiner’s study did not examine coping in response to minority stressors specific to sexual orientation. A focus on coping in response to minority stress may be particularly important given that others have documented that LGB-specific stressors are more salient for understanding heightened risk than more general stressors (e.g., Russell et al., 2012; Toomey et al., 2010). Kuper and colleagues’ study did examine coping related to LGBT stressors; however, instead of identifying a model of specific strategies used to cope with minority stressors, they identified themes of how LGBT young people persevered after a minority stressor occurred. The goal of the present study was to examine the reliability and validity of a specific measure of minority stress coping via retrospective self-reports of coping strategies used by LGB1 young people during adolescence in response to encountered sexual orientation-related minority stressors. Specifically, we sought to understand whether the minority stress coping strategies examined were differentially associated with young adult psychosocial well-being and high school-level educational attainment. In the following paragraphs we briefly review the adolescent coping literature, followed by a review of the literature that has examined how LGB adolescents cope with minority stress and the observed differential associations between various coping strategies and psychosocial adjustment.

Coping in Adolescence

The extant literature on adolescent coping largely focuses on two areas: coping responses and coping strategies (Compas, Connor-Smith, Slatzman, Thomsen, & Wadsworth, 2001; Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007). While there is no consensus on a universal adolescent coping model in the current literature (Skinner, Edge, Altman, & Sherwood, 2003), we review what has emerged as the most comprehensive, empirically-supported model of coping strategies (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007) and a broader model of coping styles (Compas et al., 2001). The model proposed by Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck (2007) includes 12 “families” of coping: problem-solving, information-seeking, helplessness, escape, self-reliance, support-seeking, delegation, social isolation, accommodation, negotiation, submission, and opposition. The three families of coping strategies that adolescents use most often include support-seeking, problem-solving, and distraction (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007). A fourth family of coping, escape, is commonly identified in studies; however, inconsistencies across studies make it difficult to draw a conclusion about the prevalence of this strategy among adolescents (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007).

Support-seeking strategies include behaviors such as sharing a problem with others, finding information from references or others to help with a problem, or comfort seeking (Lazarus, 1993; Seiffge-Krenke, 1995). By adolescence, most youth are able to identify individuals, organizations, of references that are best able to help them with a particular stressor. Peer relationships, specifically friendships, are a predominant source of support during adolescence (Bagwell et al., 2005). Problem-solving strategies are conceptualized as cognitive in nature. Specific strategies usually identified in this family of coping include decision-making, planning or strategizing, reflecting, or perspective-taking (Lazarus, 1993; Seiffge-Krenke, 1995). These strategies are used more often by older adolescents who have advanced levels of cognitive development (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007). Finally, distraction strategies, including both cognitive and behavioral forms, are used by adolescents just as often as support-seeking strategies (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck). These strategies can include thinking about other things than the stressor, keeping busy with other activities, or trying to forget the stressor (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck). For instance, adolescents may get involved with physical recreation, seek leisure activities, or may become more engaged in school or work activities. Other youth may engage in risky behaviors, such as drug or alcohol use, or self-harming behaviors to cope with stressful situations. Escape strategies include behaviors similar to distraction strategies, but are more intense reactions to stress. Examples of escape strategies include avoidance, withdrawal, and denial (Lazarus, 1993; Seiffge-Krenke, 1995). Escape strategies are generally employed when the adolescent feels that the stressor is uncontrollable (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck).

Coping in Response to LGB Minority Stress

While LGB adolescents likely use similar coping strategies as heterosexual adolescents in dealing with normative adolescent stressors (for a comprehensive review of adolescent coping, see Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007), there may be distinct ways in which LGB adolescents effectively cope with minority stress related to their sexual orientation. For instance, research has documented that many LGB adolescents obtain social support from LGB-focused groups or organizations, such as Gay-Straight Alliances (GSAs; Griffin, Lee, Waugh, & Beyer, 2004; Kosciw, Greytak, Bartkiewicz, Boesen, & Palmer, 2012). This hypothesis is consistent with the minority stress model (Meyer, 2003), which posits that group-level resources, such as LGB community connections, may be more effective at ameliorating minority stress compared to individual-level coping efforts.

Nonetheless, the coping literature focused on LGB adolescents has largely examined personal coping strategies. For example, in their qualitative study, Kuper and colleagues identified ten themes of how LGBT adolescents responded to LGBT minority stressors, which included avoidance (e.g., ignoring stressors, being guarded) and approach (e.g., becoming stronger, helping others) coping strategies. Similarly, Lock and Steiner (1999) compared LGB adolescents’ average use of avoidance and approach coping strategies to heterosexual adolescents, and found that LGB adolescents employed both avoidance and approach coping styles at higher levels compared to their heterosexual counterparts. In response to this finding, the authors suggested that LGB adolescents may encounter more frequent and varied stressors and thereby need a variety of strategies to cope successfully; however, the authors did not examine whether coping was in response to minority stress. A separate study of adults found that gay and bisexual men utilized emotion-oriented and avoidance coping strategies more often than heterosexual men (Sandfort, Bakker, Schellevis, & Vanwesenbeeck, 2009). Nonetheless, the stressors that LGB young people experience and the coping strategies available to them in adolescence are likely developmentally different than in adulthood. The current study builds on prior work by examining coping in response to LGB minority stress using retrospective reports from young adults about their adolescent experiences.

Finally, examinations of the links among coping strategies and indicators of adjustment are important for understanding the potential protective nature of coping to offer strategies to foster positive development for a range of programs and services that work with LGB young people. Compas and colleagues (2001) reviewed associations between coping strategies and psychosocial adjustment in the general adolescent population and found that approach coping strategies (e.g., support-seeking, problem solving) were generally associated with positive adjustment. On the other hand, avoidance coping strategies (e.g., escape, helplessness) were consistently found to be associated with negative adjustment (Compas et al., 2001). These findings raise the possibility that some coping strategies for LGB minority stress may promote resilience while others exacerbate risk.

Study Goals

This study presents findings from the Family Acceptance Project’s (FAP) young adult survey, a component of a community-based research and intervention initiative aimed at providing a comprehensive examination of non-Latino/a White and Latino/a LGB adolescent and young adult experiences (Ryan, 2009). To our knowledge, no study has comprehensively examined coping strategies of LGB adolescent specific to encountered sexual orientation-related minority stress via quantitative methods. The primary aim of this study was to examine the reliability and validity of a measure of minority stress coping based on LGB young adult’s retrospective reports of coping strategy use during adolescence to deal with LGB stressors. Further, because prior research has identified differential use of coping strategies across ethnicity and sex (e.g., Seiffge-Krenke, 1995), we examined whether the derived coping model was equivalent across these subpopulations in the study’s sample (i.e., across non-Latino/a White and Latino/a populations, and across young men and women). In order to establish validity, we examined the associations among sexual orientation-related minority stress coping strategies and young adult adjustment (i.e., depression, self-esteem, and life satisfaction) and high school-level educational attainment. Given prior research, we expected to find that approach-oriented coping strategies (e.g., those that emphasize support-seeking) would be associated with greater well-being and attainment greater likelihood of graduating from high school, while avoidance-oriented coping styles (e.g., those that emphasize escape) would be associated with more negative outcomes. Finally, we expected that any LGB-oriented coping strategies would be associated with positive outcomes (e.g., Meyer, 2003).

Method

Sample and Study Procedures

The participants for the Family Acceptance Project’s survey were recruited from lesbian, LGBT venues within a 100-mile radius of the San Francisco Bay Area. Specific to the goals of the larger study (see Ryan, 2010), screening procedures used to select participants into the study included the following criteria: age (21-25); ethnicity (non-Latino/a White, Latino/a or Latino/a mixed); self-identification as LGBT during adolescence (defined as ages 13-19); knowledge of LGBT identity by at least one parent or guardian during adolescence; and residence with at least one parent or guardian during adolescence at least part time. The survey was administered in both English and Spanish, and was available in either computer-assisted or paper and pencil format. The study protocol was approved by the university’s institutional review board.

The mean age of the sample was 22.84 years (SD = 1.35); 44.9% were cisgender women, 46.5% cisgender men, and 8.6% transgender. Of the 245 participants, 42.5% identified as gay, 27.8% as lesbian, 13.1% as bisexual, and 16.7% as other (e.g., queer, dyke, homosexual; note: for brevity, this population will be referred to as Queer throughout the remainder of the manuscript given that most participants in this category indicated this term). Approximately half (51.4%) the sample identified as Latino/a/a and the other half (48.6%) as non-Latino/a White young adults; 18.8% of the sample identified as immigrants to the United States. The mean level of socioeconomic status (SES) was 6.75, which was assessed from the average of two items about parental occupation (range: 1 [unskilled labor] to 16 [professional]), indicating that on average participants grew up with parents who held semi-skilled (= 4; e.g., car technician) to skilled professions (= 9; e.g., sales manager).

Measures

Coping with sexual orientation-related minority stress

Adolescent coping specific to sexual orientation-related minority stress (referred to as LGB stress) was assessed by 26 items that were derived from qualitative interviews conducted as part of the Family Acceptance Project’s LGBT youth and family qualitative study. In FAP’s qualitative study – which included 2 to 4 hour individual interviews conducted in English and Spanish with Latino/a/a and non-Latino/a/a White LGBT adolescents and families – FAP researchers elicited a list of coping strategies used by LGBT adolescents to manage minority stress. These items were then cross-checked by consultation with providers who worked with LGB youth, with other researchers who had studied LGB adolescents, and with existing adolescent coping measures (see Frydenberg & Lewis, 1996). The creation of this 26 item list was followed by talk aloud interviews with Latino/a/a and non-Latino/a/a White LGBT young adults to assess both levels of understanding and correct interpretation of these items prior to mounting the young adult survey. All of the items were asked with the stem, “Between ages 13-19, when things were difficult because of your sexual orientation, how often did you respond by...” and included 26 prompts (see Table 1 for all items). Responses were coded on a 5-point scale (0 = never to 4 = very often).

Table 1.

Rotated Factor Loadings for Coping with LGB Minority Stress Measure

| Item | LGBT-Specific | Alternative-Seeking | Cognitive Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Getting involved in LGBT groups or orgs | .489 | .067 | .149 |

| Looking for services for LGBT youth | .712 | .096 | −.068 |

| Looking for information on LGBT issues | .969 | −.035 | .024 |

| Going online or using the internet to find LGBT connections | .037 | .78 | −.161 |

| Looking for places to spend time that felt safer or more accepting | .029 | .73 | .067 |

| Trying to find an alt. living situation away from family | −.035 | .835 | .069 |

| Looking for new friends who would be more accepting | .039 | .486 | .144 |

| Spending more time by yourself to figure things out | −.049 | .034 | .792 |

| Imagining a better future for yourself | .015 | .088 | .526 |

| Just trying to put it all out of your mind | .015 | −.054 | .547 |

| Avoiding other people | .145 | −.04 | .680 |

|

| |||

| Trying to find an alt. classroom/high school that would be more accepting | |||

| Trying to appear more openly gay or lesbian | |||

| Engaging in political or social activism | |||

| Focusing on a job or employment | |||

| Engaging in creative, musical, or artistic activities | |||

| Looking for comfort & support from a romantic partner | |||

| Focusing on the positive things going on in your life | |||

| Looking to religion or spirituality for comfort | |||

| Confronting the people or situation that were causing you problems | |||

| Focusing on academic work | |||

| Looking for support from accepting family members/relatives | |||

| Looking for support from accepting adults who were not members of your family | |||

| Looking for support from friends | |||

| Choosing to get professional counseling | |||

| Writing in a journal | |||

Note. Boldface factor loadings represent the retained items for each respective factor. The item “Going online or using the internet to find LGBT connections” (italicized) was removed during measurement equivalence testing by sex. Items without factor loadings were removed in prior EFA models because of dual-loadings or factor loadings < .40.

Young adult psychosocial adjustment

Three young adult psychosocial adjustment outcomes were assessed: depression, self-esteem, and life satisfaction. The 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977, 1991) was used to measure depressive symptoms (α = .94); each item was rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (Rarely or none of the time) to 3 (Most or all of the time). The 10-item Rosenberg (1965) self-esteem scale was used to measure young adult perceptions of self-esteem (α = .88); each item was rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). An eight-item scale (α = .75) was used to measure young adult life satisfaction (e.g., Toomey et al., 2010); items were rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 4 (very satisfied).

High school attainment

One item assessed overall educational attainment: “What is the highest level of education you have completed?” (1 = less than elementary school, to 7 = post-graduate). Because participants were college-aged, we were only able to examine whether participants had completed high school. If participants checked any choice below “high school graduate”, they were coded as a high school dropout (0=graduate [88.57%], 1=dropout [11.43%]).

Overview of Analyses

We first examined the factor structure of the coping with LGB stress measure using exploratory factor analysis (EFA; DeVellis, 2003). The EFA with geomin rotation (Browne, 2001) on the 26-items was conducted using Mplus version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). Next, we examined the measurement equivalence of the coping measure and young adult outcomes across participant sex2 and ethnicity (i.e., non-Latino/a White and Latino/a) using multi-group confirmatory factor analysis (MACS; Little, Card, Slegers, & Ledford, 2007). Three hierarchically nested levels of invariance were tested: configural, weak, and strong. When invariant items were identified, they were removed from the model and the series of nested model comparisons were repeated with the reduced set of items. Finally, we examined the associations among the retrospective minority stress coping strategies and young adult psychosocial adjustment and high school attainment in a structural equation model (SEM) in Mplus. Seven covariates associated with our outcomes in previous studies were included in the final structural model: gender (cisgender women and transgender young adults compared to cisgender men), sexual orientation (bisexual and queer/other compared to gay/lesbian), ethnicity (non-Latino/a White compared to Latino/a), nativity status (born inside the U.S. versus outside the U.S.), and family-of-origin socioeconomic status (SES).

For use in SEM, we created three parcels for the life satisfaction and self-esteem latent constructs, respectively. This method creates more structurally stable latent constructs (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002). The four CES-D subscales were respectively parceled into four manifest variables used as the structure for the latent construct of depression (i.e., facet-representative parceling; Little et al, 2002). We used standard measures of practical fit to examine all models: the comparative fit index (CFI) and the root-mean-squared error of approximation (RMSEA). Chi-square difference tests were used to examine nested model comparisons. Missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood (FIML; Arbuckle, 1996; Schafer, & Graham, 2002).

Results

Exploratory Factor Analyses

The initial EFA on the 26-items revealed five factors with eigenvalues greater than 1. Items that cross-loaded or had a factor loading of <.40 were not retained. Items were removed one-by-one and the EFA was repeated. The final EFA model resulted in 11 items being retained and three factors (see Table 1). The three distinct coping strategies identified by the EFA included LGBT-specific coping (α = .82), alternative-seeking (α = .79), and cognitive strategies (α = .78). This model had acceptable fit: χ2 (df = 41) = 90.30, p < .001; RMSEA = .07 (90% C. I.: .05 - .09); CFI = .95.

Measurement Invariance by Sex and Ethnicity

Next, we completed multi-group confirmatory factor analyses to test for measurement invariance of the measure across participant sex (i.e., male and female) and ethnicity (i.e., non-Latino/a White and Latino/a). Examining invariance across multiple groups allows for generalizations to be made about whether the measurement and processes under investigation work similarly for all participants. To assess invariance, we examined configural, weak, and strong invariance of measurement across sex and ethnicity, separately. These tests examine whether the patterns of factor structure, factorial loadings, and mean intercept loadings can be equated across groups (Little, 1997).

We first examined measurement invariance across sex. Configural and weak invariance were demonstrated (see Table 2); however, strong invariance was not obtained. Thus, a series of nested model comparisons were tested to identify which item(s) contributed significantly to the measurement variance across sex. The item that significantly contributed to the measurement variance was: “Between ages 13-19, when things were difficult because of your sexual orientation, how often did you respond by going online or using the internet to find LGBT connections?” Males reported significantly higher levels of seeking connections online compared to females. Because this item was not equivalent across groups, it was removed from the final model. After this item was removed, results indicated that our revised measurement model with 10 items and 3 factors was equivalent across sex (see Table 2). Further, measurement invariance was demonstrated across ethnicity (Table 2). Thus, in the absence of sex and ethnicity measurement differences, we collapsed all participants into one group for subsequent analyses.

Table 2.

Measurement Equivalence by Sex and Ethnicity: Results of Nested Model Comparisons

| Model | χ 2 | df | p | RMSEA | 90% CI | CFI | Constraint Tenable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex – With LGBT online item | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Configural Invariance | 146.371 | 82 | 0.00 | 0.08 | (0.059, 0.101) | .932 | --- |

| Weak Invariance | 160.911 | 90 | 0.00 | 0.08 | (0.06, 0.10) | .925 | Yes |

| Strong Invariance | 197.04 | 98 | 0.00 | 0.091 | (0.072, 0.109) | .895 | No |

|

| |||||||

| Sex – Without LGBT online item | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Configural Invariance | 109.587 | 64 | 0.0003 | 0.076 | (0.051, 0.10) | 0.947 | --- |

| Weak Invariance | 121.378 | 71 | 0.0002 | 0.076 | (0.052, 0.099) | 0.941 | Yes |

| Strong Invariance | 132.722 | 78 | 0.0001 | 0.076 | (0.053, 0.097) | 0.936 | Yes |

|

| |||||||

| Ethnicity – Without LGBT online item | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Configural Invariance | 98.212 | 64 | 0.0038 | 0.066 | (0.038, 0.091) | 0.959 | --- |

| Weak Invariance | 108.314 | 71 | 0.0029 | 0.065 | (0.039, 0.089) | 0.955 | Yes |

| Strong Invariance | 113.036 | 78 | 0.0058 | 0.061 | (0.033, 0.084) | 0.958 | Yes |

Note. A change in CFI that is > .01 suggests that measurement invariance is not tenable (Little et al., 2007).

Minority Stress Coping and Well-Being

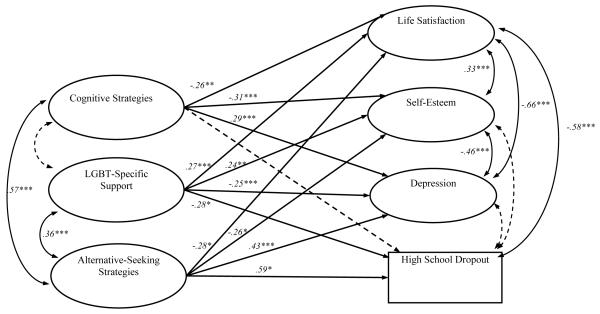

We tested the associations among retrospectively reported adolescent minority stress coping strategies, young adult well-being, and high school attainment in a structural equation model. This model (see Figure 1) had good fit: χ2 (df =267) = 338.57, p = .002; RMSEA = .03 (90% C. I.: .02 - .04); CFI = .93. At the bivariate level, women (r = −.20, p < .01) and bisexual young adults (r = −.17, p < .05) reported using fewer alternative-seeking strategies, whereas economically disadvantaged respondents (r = .32, p < .001), transgender respondents (r = .16, p < .05), queer young adults (r = .17, p < .01), and young adults born outside of the U.S. (r = .21, p < .01) reported using more alternative-seeking strategies. Being Latino/a (r = .01, p = .92) was not differentially associated with the use of alternative-seeking strategies. Participants who identified as queer (r = .24, p < .001) and Latino/a (r = .17, p < .05) participants reported using LGBT-specific strategies more often than lesbian or gay and non-Latino/a participants, respectively. Finally, economically disadvantaged participants (r = .21, p < .01) used cognitive strategies more often than those who were economically advantaged.

Figure 1. Associations among Retrospectively-Reported Adolescent Coping Strategies and Young Adult Adjustment.

Note. Standardized solution shown. All factor loadings were significant at p < .001 level and are not shown for clarity. Solid pathways are significant and dotted pathways are not significant. The model includes seven sociodemographic covariates: gender (females and transgender individuals compared to males), sexual orientation (bisexual and queer compared to gay/lesbian), ethnicity (Non-Latino/a Whites compared to Latino/as), immigrant status (immigrants compared to non-immigrants), and SES (continuous measure). * p < .05. **p < .01. *** p < .001.

Retrospectively-reported minority stress coping strategies were differentially associated with young adult well-being and high school attainment (see Figure 1 for standardized estimates). LGB-specific coping was associated with higher self-esteem, greater life satisfaction, fewer depressive symptoms, and less likelihood of having dropped out of high school. On the other hand, alternative-seeking coping was associated with lower self-esteem and life satisfaction, greater depressive symptoms, and a greater likelihood of having dropped out of high school. Use of cognitive coping strategies to deal with sexual orientation minority stress was also associated with lower self-esteem and life satisfaction and greater depressive symptoms.

Discussion

It is imperative to understand how LGB adolescents cope with minority stress, given that stressors related to sexual orientation are a key indicator of well-being (Meyer, 2003; Russell et al., 2012). This study provides initial support for the reliability and validity of a measure that contains three coping strategies that LGB adolescents may utilize to deal with LGB minority stress: LGB-specific strategies, alternative-seeking strategies, and cognitive strategies. Importantly, the modified coping measure was equally valid across participant sex (i.e., male and female) and ethnicity (i.e., Latino/a and non-Latino/a White), suggesting that the items measure the same constructs for males and females, as well as for Latino/as and non-Latino/a Whites. The differential associations that we documented among these coping strategies and young adult well-being suggests that some of these strategies may enhance risk (i.e., alternative-seeking and cognitive strategies), while others, LGB-specific coping strategies, may confer protection.

A key difference in this study’s measure of coping compared to existing, comprehensive measures of adolescent coping (e.g., Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007), is the identified LGB-specific coping strategy in this sample (see Table 1 for items); consistent with the minority stress framework (Meyer, 2003), it highlights the importance of belonging to and having access to an LGB community. LGB-specific strategies blend several of the coping strategies identified in the current adolescent literature, and the items appear to be most aligned with support-seeking strategies (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007). Adolescents who navigate LGB minority stress may need to seek support that is specific to LGB issues; these support needs are distinctly different from seeking general support from family members and peers, most of whom are heterosexual and do not have consistent and regular experiences with homophobia or heterosexism. Doty and Malik (2009) found that sexuality-related social support buffers the association between sexuality-related stress and adjustment, whereas non-sexuality related social support does not have the same protective result for LGB adolescents. Thus, the type of support that is needed should match the type of stress affecting an individual (Doty & Malik,). Our findings suggest that looking for or getting involved in LGB organizations or support groups for LGB individuals are specific coping strategies that are particularly meaningful for LGB adolescents. Notably, this strategy was the only one identified that was associated with more positive well-being and academic outcomes, suggesting that it may be beneficial to incorporate in models of LGB adolescents resilience.

Our conceptualization of alternative-seeking strategies (see Table 1 for items) is consistent with the general adolescent coping strategy of escape (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007). For LGB adolescents, the need to seek alternatives may arise because of hostile or rejecting environments in which the adolescent may not have control (e.g., parents may kick the adolescent out of the house after disclosure of sexual orientation or teachers may not intervene in homophobic harassment at school). Future research should examine the underlying processes that thwart the efforts of adolescents to seek alternatives, as well as identify ways to support them if there are few available alternatives. Importantly, alternative-seeking strategies were negatively associated with young adult well-being and a greater risk for having dropped out of high school; clearly there is a need to prevent the need for LGB adolescents to seek out alternative living situations (e.g., homelessness) or classrooms (e.g., alternative schools). Programs and policies that support marginalized adolescents need to identify or successfully implement strategies for creating LGB-supportive environments (e.g., Poteat & Russell, 2013).

Finally, the cognitive coping strategy (see Table 1 for items) identified in this study is consistent with a family of cognitive strategies identified in the general coping literature, such as cognitive distraction (e.g., Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007). Consistent with prior research (Garnefski, Legerstee, Kraaij, van den Kommer, & Teerds, 2002; Kraaij et al., 203), we found that cognitive coping was associated with poorer well-being, suggesting that programs that support positive youth development may help adolescents to identify, learn, and practice healthier coping mechanisms. Future research on coping in populations that experience minority stressors may examine other cognitive strategies, such as mindfulness or acceptance approaches, as they have been shown to reduce negative outcomes and use of problematic coping mechanisms, such as rumination (e.g., Mendelson, Greenberg, Dariotis, Gould, Rhoades, & Leaf, 2010).

Limitations and Future Directions

Our research presents support for a specific measure of how LGB adolescents cope with minority stress and provides initial evidence of the possibility for resilience and risk from use of specific strategies. Nevertheless, our study has several limitations. First, the retrospective nature of the information about adolescent coping strategies limits the ability to draw conclusions about causality and associations with young adult adjustment. Similarly, we lack information about adolescent adjustment and therefore cannot control for previous levels of depressive symptoms, life satisfaction, or self-esteem. Future research needs to examine the validity and reliability of this measure with young people in adolescence and examine its associations with well-being and academic achievement using prospective methods.

Second, our sample is geographically homogenous and is not representative of all LGB adolescents. Notably, however, our sample included a large percentage of Latino/a LGB-identified individuals, a relatively large percentage of immigrants, and represented a range of socioeconomic status – groups that are commonly underrepresented in studies of LGB young people. Future research should examine our LGB minority stress coping model with samples that are geographically heterogeneous and more diverse. It will also be important for these strategies to be assessed by adolescents who are not out to parents or other family members, who are in the process of identity development and integration (e.g., those who may be questioning their sexual orientation and/or gender identity), and who are from other underrepresented populations (e.g., Black or Asian LGB adolescents).

Conclusions

We derived three strategies that LGB adolescents utilize to cope with LGB minority stress, illuminated the role of LGB-specific coping strategies as a possible resilience factor, and highlighted the benefits of access to LGB-related information, support, and involvement in LGB-related groups. These findings move the field of research on LGB young people forward by providing information about the sources of strength and resilience for this population. Also important, we found negative associations between alternative-seeking and cognitive strategies and young adult well-being – a finding that highlights the need to focus on policy, prevention, and intervention strategies to promote safe environments for LGB adolescents. This finding also has implications for the adults in LGB adolescents’ lives: parents and other family members, school personnel, and adult community members can help create safe, supportive environments for LGB young people so they are not forced to find a way to escape, but instead, can use positive coping strategies that increase support, promote well-being, and focus on skills and abilities that further life course development. For example, accepting family behaviors identified and measured in prior research from the Family Acceptance Project found that parent and caregiver reactions such as finding a positive adult role model to give their LGB child options for the future; taking them to LGBT community organizations or events; and giving them positive reading materials and resources to help them accept their identity helped protect against health risks and predicted greater well-being in young adulthood (Ryan et al., 2010).

There remains a notable gap in prevention and intervention strategies tailored for LGB young people (Russell, 2005; Mustanski, Birkett, Greene, Hatzenbuehler, & Newcomb, 2014). Coping related to seeking positive sources of support and investing in academic and creative interests appear to offer promising strategies to foster positive development for a range of programs and services that work with LGB young people, including those who are more vulnerable. These strategies may be useful if translated to other marginalized groups who experience minority stress.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of our funder, The California Endowment, and the contribution of our community advisory groups and the many adolescents, families and young adults who shared their lives and experiences with us. Support for this project was also provided by a Loan Repayment Award by the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (L60 MD008862; Toomey).

Footnotes

Our sampling frame included young adults who identified as LGBT during adolescence (see Ryan, 2010). All of the transgender young adults in this sample also identified as lesbian/gay, bisexual, homosexual, or queer. Because of the focus on coping with sexual orientation-related stressors in this paper, the LGB acronym is used to describe the sample throughout the manuscript.

Sex assigned at birth (i.e., male and female) was used for the group variable in these analyses given that the cell size for transgender for was too small to examine invariance by gender identity (i.e., men, women, and transgender person).

References

- Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1996. pp. 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW. An overview of analytic rotation in exploratory factor analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2001;36:111–150. [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, Wadsworth ME. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:87–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig SL. Affirmative Supportive Safe and Empowering Talk (ASSET): Leveraging the strengths and resiliencies of sexual minority youth in school-based groups. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling. 2013;7:372–386. [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis RF. Scale development: Theory and applications. 2nd ed Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Doty ND, Malik NM, Willoughby (Chair) B. Sexuality related social support and psychological distress among same-sex attracted youth. Relational resilience among same-sex attracted youth: The protective roles of LGBTQ friends, straight friends, and family members; Symposium conducted at the Society for Research in Child Development Biennial Meeting; Denver, Colorado. Apr, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Gruen RJ, DeLongis A. Appraisal, coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50(3):571–579. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.50.3.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydenberg E, Lewis R. A replication study of the structure of the Adolescent Coping Scale: Multiple forms and applications of a self-report inventory in a counselling and research context. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. 1996;12:224–235. [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski N, Legerstee J, Kraaij V, van den Kommer T, Teerds J. Cognitive coping strategies and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A comparison between adolescents and adults. Journal of Adolescence. 2002;25:603–611. doi: 10.1006/jado.2002.0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbach JT, Gibbs J. Strategies employed by sexual minority adolescents to cope with minority stress. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2015;2:297–306. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin P, Lee C, Waugh J, Beyer C. Describing roles that gay-straight alliances play in schools: From individual support to change. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Issues in Education. 2004;1:7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Bartkiewicz MJ, Boesen MJ, Palmer NA. The 2011 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth in our nation’s schools. GLSEN; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kraaij V, Garnefski N, de Wilde EJ, Dijkstra A, Gebhardt W, Maes S, ter Doest L. Negative life events and depressive symptoms in late adolescence: Bonding and cognitive coping as vulnerability factors? Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2003;32:185–193. [Google Scholar]

- Kuper LE, Coleman BR, Mustanski BS. Coping with LGBT and racial-ethnic-related stressors: A mixed-methods study of LGBT youth of color. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2013;24:703–719. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Coping theory and research: Past, present, and future. Psychometric Medicine. 1993;55:234–247. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD. Means and covariance structures (MACS) analyses of cross-cultural data: Practical and theoretical issues. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1997;32:53–76. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3201_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Card NA, Slegers DW, Ledford E. Representing contextual effects in multiple-group MACS models. In: Little TD, Bovaird JA, Card NA, editors. Modeling contextual effects in longitudinal studies. Routledge; New York: 2007. pp. 121–148. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, Widaman KF. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:151–173. [Google Scholar]

- Lock J, Steiner H. Relationships between sexual orientation and coping styles of gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents from a community high school. Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association. 1999;3:77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Dietz LJ, Friedman MS, Stall R, Smith HA, McGinley J, Brent DA. Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;49:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson T, Greenberg MT, Dariotis JK, Gould LF, Rhoades BL, Leaf PJ. Feasibility and preliminary outcomes of a school-based mindfulness intervention for urban youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:985–994. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9418-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Birkett M, Greene GJ, Hatzenbuehler ML, Newcomb ME. Envisioning an American without sexual orientation inequities in adolescent health. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104:218–225. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. MPlus user’s guide. Seventh Edition Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Russell ST. Understanding homophobic behavior and its implications for policy and practice. Theory Into Practice. 2013;52:264–271. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The use of the center for epidemiological studies depression scale in adolescents and young adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1991;20:49–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University; Princeton, NJ: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST. Beyond risk: Resilience in the lives of sexual minority youth. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Issues in Education. 2005;2:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Fish JN. Mental health in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2016;12:465–487. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Sinclair KO, Poteat VP, Koenig BW. Adolescent health and harassment based on discriminatory bias. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:493–495. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C. Supportive families, healthy children: Helping families with lesbian, gay, bisexual & transgender children. Marian Wright Edelman Institute, San Francisco State University; San Francisco, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in White and Latino/a lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123:36–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandfort TGM, Bakker F, Schellevis F, Vanwesenbeeck I. Coping styles as mediator of sexual orientation-related health. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009;38:253–263. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(2):147–177. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I. Stress, coping, and relationships in adolescence. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, Edge K, Altman J, Sherwood H. Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:216–269. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. The development of coping. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:119–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, Ryan C, Diaz R, Card NA, Russell ST. Gender nonconforming lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: School victimization and young adult psychosocial adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:1580–1589. doi: 10.1037/a0020705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Træen B, Martinussen M, Vittersø J, Saini S. Sexual orientation and quality of life among university students from Cuba, Norway, India, and South Africa. Journal of Homosexuality. 2009;56:655–669. doi: 10.1080/00918360903005311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsemann KM, Lindley LL, Gentile D, Welihindha SV. Educational attainment by life course sexual attraction: Prevalence and correlates in a nationally representative sample of young adults. Population Research and Policy Review. 2013;33:579–602. doi: 10.1007/s11113-013-9288-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziyadeh NJ, Prokop LA, Fisher LB, Rosario M, Field AE, Camargo CA, Austin SB. Sexual orientation, gender, and alcohol use in a cohort study of U.S. adolescent girls and boys. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;87:119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]