Abstract

The taxa of Astragalus section Hymenostegis are an important element of mountainous and steppe habitats in Southwest Asia. A phylogenetic hypothesis of sect. Hymenostegis has been obtained from nuclear ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and plastid ycf1 sequences of up to 303 individuals from 106 species, including all 89 taxa currently assigned to sect. Hymenostegis, 14 species of other Astragalus sections, and two species of Oxytropis and one Biserrula designated as outgroups. Bayesian phylogenetic inference and parsimony analyses reveal that three species from two other closely related sections group within sect. Hymenostegis, making the section paraphyletic. DNA sequence diversity is generally very low among Hymenostegis taxa, which is consistent with recent diversification of the section. We estimate that diversification in sect. Hymenostegis occurred in the middle to late Pleistocene, with many species arising only during the last one million years, when environmental conditions in the mountain regions of Southwest and Central Asia cycled repeatedly between dry and more humid conditions.

Introduction

Astragalus is with about 2500–3000 species in 250 sections the largest genus of flowering plants1–7. It belongs to the legume family (Leguminosae or Fabaceae) that is, after Orchidaceae and Asteraceae, the third largest family of flowering plants5 consisting of about 730 genera and nearly 19,300 species. Also its subfamily Papilionoideae, with about 478 genera and 13,800 species5, is very species rich. Astragalus belongs within this subfamily together with genera like Oxytropis and Colutea to the Astragalean clade of the so-called Inverted Repeat Lacking Clade (IRLC). Its members are all characterized by the loss of one copy of the two 25-kb inverted repeat regions in the chloroplast genome2,8–10.

Although species richness seems to be a general characteristic of the legumes, this feature is not evenly distributed among the groups within this family. Thus, Sanderson and Wojciechowski11 found that Astragalus itself is not significantly more speciose compared to its close relatives, but that species richness is a feature of the entire Astragalean clade in comparison to the other groups of the IRLC. High species numbers can originate through constant accumulation of diversity through time or following a punctuated pattern, where bursts of diversification rates alternate with times of stasis12. The latter pattern often results from the evolution of a key innovation that provides the possibility to fill a new ecological niche, or from a key opportunity, i.e. the colonization of a new, formerly not inhabited area and speciation therein12–15. For Astragalus and the entire Astragalean clade the reason(s) for the high species numbers are still unclear. In an effort to better understand reasons for and timing of species diversification in Astragalus we here analyze a large section of the genus, where we put some effort into arriving at a complete species sample.

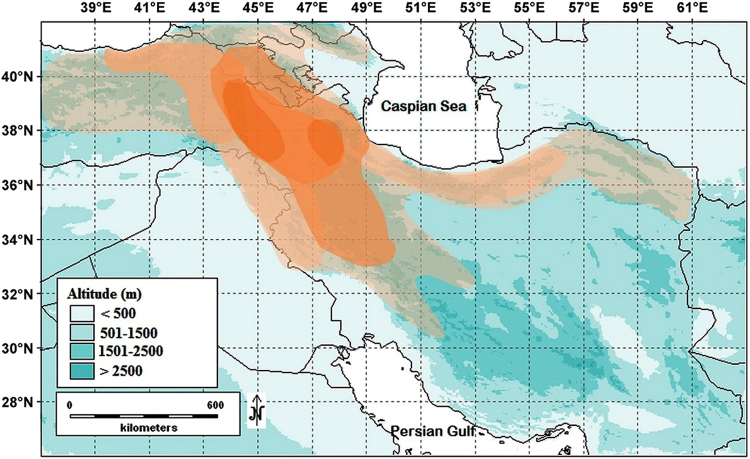

Astragalus section Hymenostegis Bunge was validly published by Bunge16,17 including originally 23 species, and was typified with A. hymenostegis Fisch. & C.A.Mey.18. Section Hymenostegis has been revised several times7,19–22. It is one of the largest sections of Old World Astragalus, distributed mainly in Iran and Turkey23,24. Of the total number of 89 currently recognized species (Bagheri et al., unpublished data), 85 (95.5%) occur in Iran (Fig. 1), from which 71 (79.8%) are endemic to this country7,23–28. Members of sect. Hymenostegis are morphologically characterized by an inflated calyx, basifixed white hairs, and wide and conspicuous bracts. The section was subdivided by Zarre and Podlech21 into two subsections: subsect. Hymenocoleus (Bunge) Podlech & Zarre, including only the Turkish endemic A. vaginans DC., and subsect. Hymenostegis. This division has been based on leaf and stem characters. Podlech and Zarre7 followed this treatment in their most recent account of Old World Astragalus. Based on an analysis of the nuclear ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of Astragalus, sect. Hymenostegis (represented by few taxa only) is nested within a clade including tragacanthic Astragalus along with other major groups of spiny Astragalus sections (including: Anthylloidei, Tricholobus, Acidodes, Poterion, Campylanthus and Microphysa) and seems to be non-monophyletic29–31. Up to now no detailed molecular phylogenetic analysis using multiple DNA loci and an exhaustive taxon sampling has been conducted for sect. Hymenostegis. Here we describe a study of this taxon based on the nuclear ribosomal DNA (rDNA) internal transcribed spacer region (ITS) and chloroplast ycf1 sequences for phylogenetic reconstruction, two marker regions which are among the fastest evolving DNA parts found up to now in Astragalus. The main purposes of our study are: (i) to assess the monophyly of sect. Hymenostegis, (ii) to examine the evolutionary relationships within this section and to closely related taxa, and (iii) to roughly estimate diversification times for the species within the section and put this in the context of the generally high species diversity within the genus and family.

Figure 1.

Map of the distribution area of the sect. Hymenostegis species. Brown shading indicates differences in species numbers per area from 1–2 (light brown) species to 25–30 species (dark brown)65.

Results

Phylogenetic analyses of ITS, ycf1, and combined ITS + ycf1 sequences

The alignment of the ITS dataset containing one individual each per species (ITS_106)

Had a length of 621 positions, with 124 variable characters of which 71 were parsimony informative. The parsimony analysis resulted in 359 trees of length 192 with a consistency index (CI) of 0.755 and a retention index (RI) of 0.880. The consensus tree is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1 (all figures indicated by “S” are provided as supplementary materials).

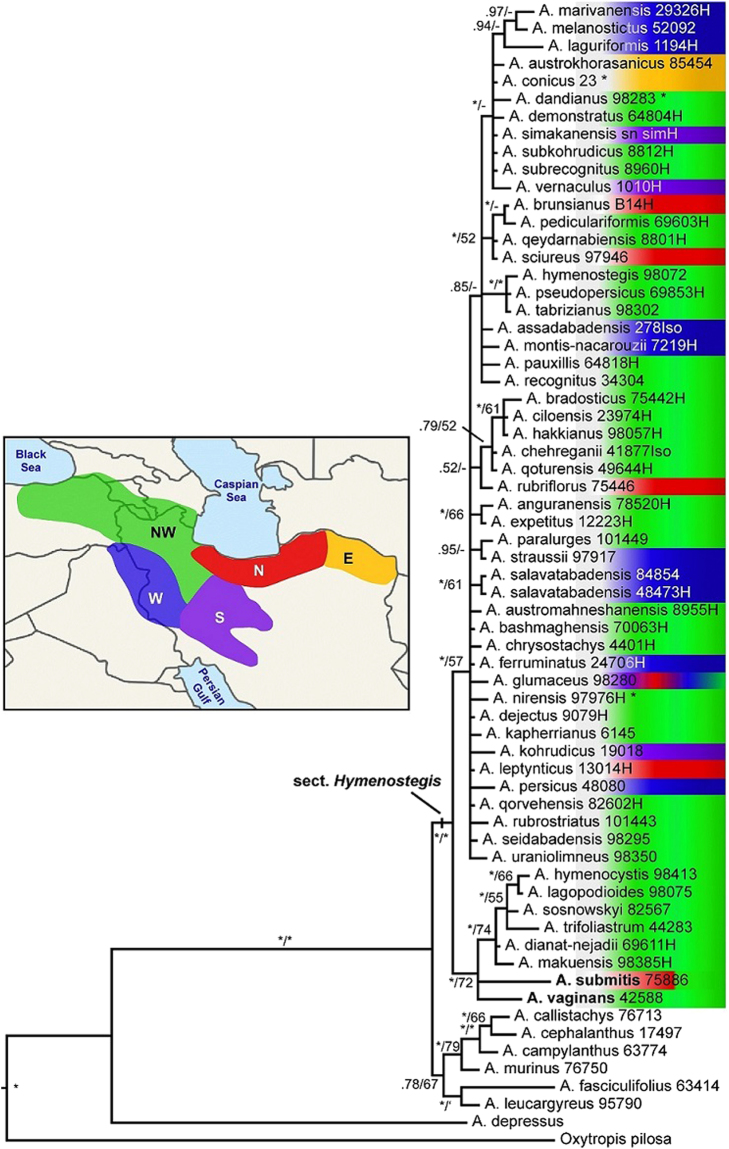

The two Bayesian phylogenetic (BI) analyses conducted with this dataset (Nst = 6 vs. Nst = 2) resulted in trees with identical topologies and very similar posterior probabilities (pp) for clades. Only one tree is therefore provided (Fig. 2). Also the maximum-likelihood (ML) analysis resulted in very similar species relationships (Supplementay Fig. S2). In these trees the assumed outgroup species Biserrula pelecinus groups within Astragalus with high support values (see Materials and Methods). Sequence differences among sect. Hymenostegis taxa are generally low resulting also in low clade support values. Nine groups, consisting mainly of taxa with identical ITS sequences, are present, the largest with 36 species, smaller clades containing nine, five, four, three and two species sharing their ITS sequence. Three species (A. submitis, A. tricholobus and A. vaginans), assumed to belonging to other sections of the genus, fall inside sect. Hymenostegis.

Figure 2.

Bayesian phylogenetic tree based on nrDNA ITS sequences and including one individual per sect. Hymenostegis species. Clade support values (BI pp/MP bs) are given at the branches of the tree. Asterisks at branches indicate pp ≥ 0.98 and bs ≥ 80%, respectively. Blue numbers provide mean node ages in million years estimated through a Beast analysis. Asterisks behind species names indicate new species names currently in the process of valid publication, while species names given in bold face mark species formerly not included within sect. Hymenostegis. Colors of species names refer to distribution areas given in Fig. 3.

The alignment of the ITS sequences for all individuals (ITS_303)

Included 282 individuals from sect. Hymenostegis taxa, 19 from other Astragalus sections, and two outgroup species. The alignment had a length of 628 positions, of which 506 characters were constant and 85 potentially parsimony informative. The 10,000 most parsimonious trees (max tree limit) had a length of 185 steps (CI = 0.768, RI = 0.948). The ML analysis and BI analyses based on the two different models of DNA sequence evolution resulted in identical tree topologies and support values for the same clades. Therefore, only one tree is provided (Supplementary Fig. S3).

The monophyly of sect. Hymenostegis (including the three species mentioned above) is highly supported (pp 1, bs 100%) but taxon resolution within the section is relatively low, i.e. many species share identical ITS sequences, also in cases where these species are morphologically easily discernable. Some small subclades are present within the tree, although they rarely received reasonable clade support values. In this dataset we included between one and six accessions per species, which allows us to infer some cases of non-monophyly for species. Thus, in A. chrysostachys, taxa listed as varieties within the species (var. parisiensis, var. dolichourus, var. khorasanicus), group apart from the other A. chrysostachys accessions at two different positions in the tree. Varieties dolichourus and khorasanicus share ITS sequences and morphology with A. conicus where they might be taxonomically belonging. In case of var. parisiensis probably a new name has to be assigned.

The aligned data matrix for the ycf1

Data consisted of 1607 characters across 65 accessions including the outgroup species. 1571 characters were constant, and of the 36 variable characters 34 were potentially parsimony informative. The 3648 most parsimonious trees had a length of 183 steps (CI = 0.934, RI = 0.882). Due to the small differences among the ycf1 sequences, phylogenetic resolution is very low in the MP tree as well as the BI analysis of this dataset. As we obtained for all these individuals also ITS sequences, we do not show these trees but use ycf1 together with the respective ITS sequences in a combined data matrix.

The partition-homogeneity test of ITS and ycf1 datasets

For the same 65 taxa carried out in Paup* 4.0a150 indicated no major conflicts between both loci. They were therefore combined in a concatenated data matrix for MP, ML and BI analyses.

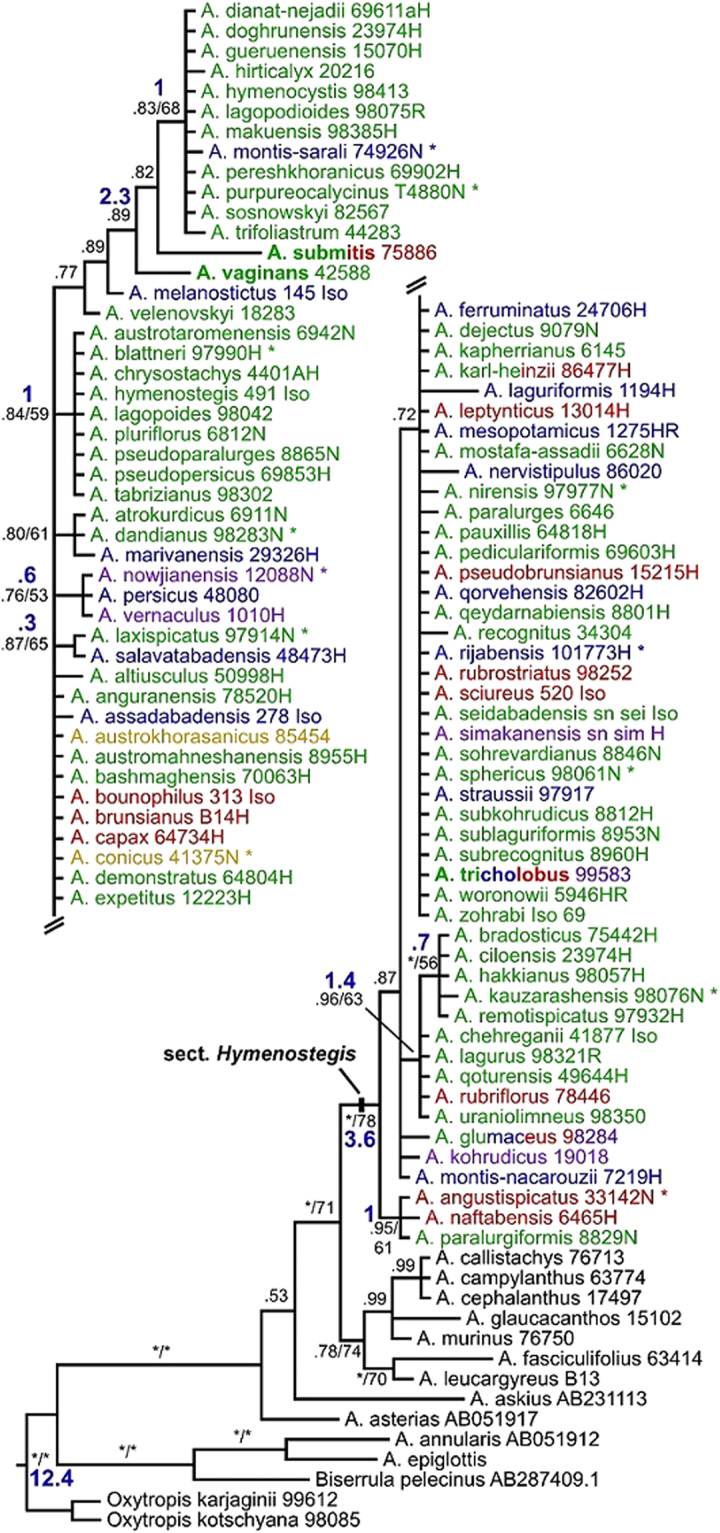

The combined ITS + ycf1

Data matrix consists of 2222 characters across 65 accessions including the outgroup species. 1981 characters were constant, and of the 163 variable characters 78 were potentially parsimony informative. The 216 most parsimonious trees had a length of 305 steps (CI = 0.879, RI = 0.853). BI analysis of the partitioned data resulted in the phylogenetic tree provided as Fig. 3, the ML result is provided as Supplemetary Fig. S4.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree obtained by Bayesian phylogenetic inference of the combined nuclear rDNA ITS and chloroplast ycf1 datasets of 64 Astragalus and one outgroup accession. Clade support values (BI pp/MP bs) are given at the branches of the tree. Asterisks at branches indicate pp ≥ 0.98 and bs ≥ 80%, respectively. Asterisks behind species names indicate new species names currently in the process of valid publication, while species names given in bold face mark species formerly not included within sect. Hymenostegis. Regions of origin of the species are color-coded and the areas are provided in the inserted map65.

Combining both datasets did not result in a substantial increase of phylogenetic resolution in comparison to the ITS dataset, although support values for clades increased. Thus, sect. Hymenostegis received maximal support and for several of the smaller species groups within this section reasonable support values were obtained. Also within the combined data several species cannot be discerned based on the sequences of both marker loci.

Age estimations for sect. Hymenostegis

The MCC tree (Supplementary Fig. S5) resulted in a topology similar to the ITS_106 tree inferred with MrBayes except for the clade consisting of A. vaginans, A. submitis and 12 other species being sister to all other sect. Hymenostegis species. This specific topology is then in accord with the ITS + ycf1 topology. The analysis inferred a mean substitution rate of 2.44 × 10−9 (substitutions/site/year) and resulted in a crown group age of sect. Hymenostegis of 3.55 My (95% HPD = 2.13–5.08) with the majority of speciation events being younger than 1.5 My (Supplementary Fig. S5). The ages of the major nodes are given in the phylogenetic tree provided as Fig. 2.

Discussion

Monophyly of Astragalus and section Hymenostegis

In our analyses Biserrula pelecinus groups within Astragalus, which confirms Wojciechowski’s32 suggestion to treat it as Astragalus pelecinus (L.) Barneby as part of the genus and regard Biserrula pelecinus L. as a synonym of this taxon.

Astragaalus tricholobus, A. submitis and A. vaginans from other closely related sections were placed among the species of sect. Hymenostegis. Thus, sect. Hymenostegis is paraphyletic when these three species are not included. This finding is consistent with the results of Kazempour Osaloo et al. (2003, 2005) and Naderi Safar et al.29–31. Astragalus submitis shares some morphological characters with members of sect. Hymenostegis, including the spiny form and inflated calyx at fruiting time. Although, due to its parapinate (not imparipinnate) leaflets and the possession of black and white (not just white) hairs it has been placed in sect. Anthylloidei 7,20–22. Astragalus vaginans shares white hairs (absence of black hairs) and imparipinnate leaflets with the members of sect. Hymenostegis, but differs by its elongated stems, long internodes of up to 1.5 cm, and remote leaves7,21 from the other sect. Hymenostegis species. This species was initially placed in the monotypic section Hymenocoleus, which was later reduced to subsection Hymenocoleus within sect. Hymenostegis 7,21. In our analyses it groups together with A. submitis plus several other sect. Hymenostegis species, providing no clear evidence that would support a separate treatment of this species within a subsection of its own. However, as A. submitis and A. vaginans exhibit an assemblage of mixed morphological characters and are also, in the context of the otherwise quite uniform ITS and ycf1 sequences in sect. Hymenostegis, relatively different in their DNA characteristics, we speculate that these species could be of hybrid origin. The ITS region did not provide any indications of polymorphic sequence positions in these taxa. This does, however, not exclude reticulate evolution, as the ITS region is prone to fast sequence homogenization33,34. Therefore, analyzing nuclear single-copy genes35,36 together with a closer evaluation of the morphological characters might be an appropriate way to test this hypothesis.

Astragalus tricholobus is nested in the main clade of sect. Hymenostegis, sharing its ITS sequence with many other core-Hymenostegis species. We could not obtain a ycf1 sequence for this species, which is the reason that it is lacking from the combined dataset. Morphologically A. tricholobus shares many characters like spiny forms, absence of black hairs, imparipinnate leaflets with sect. Hymenostegis taxa, although according to Zarre and Podlech (1996), Podlech and Maassoumi (2001) and Podlech and Zarre7,21,22 it is assumed to be member of sect. Campylanthus or sect. Tricholobus 20,37. In contrast to the two former species, which show a mixture of typical and atypical characters of sect. Hymenostegis, the morphological and molecular characters unambiguously place A. tricholobus in sect. Hymenostegis.

Ages and relationships within section Hymenostegis

Generally, the DNA sequences analyzed provide relatively few differences for sect. Hymenostegis taxa (Figs 2 and 3). However, two major groups can be discerned within the section. The ITS as well as the combined dataset resulted in a clade of species including A. vaginans, A. submitis, together with additional taxa closely related to A. dianat-nejadii and A. hymenocystis, with reasonable support values in the latter dataset. This clade is in the Beast analysis and the combined dataset the sistergroup to all other species within the section, while in the ITS trees inferred with MrBayes it forms either a clade within these other species (Fig. 2) or occurs at an unresolved polytomy with other sect. Hymenostegis species groups (Supplementary Fig. S2). Due to these inconsistencies and the small genetic differences found, we can draw no conclusions about the internal taxonomic structure of the section from our datasets. The main feature of the group seems to be the very small molecular diversity in sect. Hymenostegis in comparison to the morphological well differentiated species belonging to this taxon.

Essentially, there are two reasons for low phylogenetic resolution among species. This could be due to (i) the inappropriate choice of molecular marker regions selected. In our study we used, however, with the nrDNA ITS region the fastest evolving universal nuclear marker, and the ycf1 gene that provided the best resolution in earlier Astragalus studies38. Therefore, we assume that (ii) we deal here with a very rapid radiation, i.e. many nearly simultaneous speciation events resulting in fast changes of morphological characters, which are not equally accompanied by changes in the (neutral) marker regions we used for our study. Here using next-generation sequencing approaches to screen for genome-wide DNA differences seems a more suitable approach to us for resolving such narrow species groups39–41. Moreover, these methods could simultaneously identify genome regions contributing to fast morphological changes. However, given the high species numbers within Astragalus, the Astragalean clade, Papilionoideae, and the entire Fabaceae, the rapid and young radiation we infer here for sect. Hymenostegis is not a phenomenon exclusive to this section but seems to be a general feature of Astragalus 11 if not for many groups within the entire family42–44. Generally, finding an analysis method that could resolve species and species groups within Astragalus much better would allow analyzing parallel rapid radiations on a global scale45–47 and, thus, infer causes for the species richness observed in the Astragalean clade. For this we want to employ next a RAD-seq analysis40 in this section to explore the potential of such methods to obtain higher species resolution in Astragalus.

Molecular dating places the separation of sect. Hymenostegis from other spiny sections of Astragalus into the middle Pliocene (~4 My ago) and the majority of speciation events within the section to the last 1 My. Although these ages should be taken with some caution, as they are resting on a secondary calibration point, and the rather recent crown-group age of section Hymenostegis of 3.5 My bases such estimations on only few molecular differences, the low genetic diversity found in both phylogenetic markers supports at least a rather recent diversification of the group. During this time the typical steppe habitats of the sect. Hymenostegis species were repeatedly shrinking and expanding due to the Pleistocene climate cycles, resulting in a constant shift between humid times, characterized by expanding forests, and dry periods where the steppes expanded again48–51. It was already shown that these climate cycles could drive diversification in plant species through repeated subdivisions of populations resulting in allopatric speciation followed by range expansion when climate conditions became again favorable44,52–55. We here hypothesize that this mechanism might have played an important role also in the Astragalus species of the Irano-Turanian steppe regions.

Although we used the fastest evolving marker regions known for Astragalus, we obtained only rather low resolution within the phylogeny of sect. Hymenostegis. This prevents us from providing a reasonable biogeographic scenario for the taxon group. We can only show that the highest species number occurs in the Northwest of the distribution area of the section, i.e. northwestern Iran and eastern Turkey. Species from this area can be found in all clades within the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 3), which could be interpreted as an initial radiation of the sect. Hymenostegis in this region followed by multiple dispersals out of this area into neighboring regions. Towards the South, East and West, species diversity sharply drops. This is probably due to the lack of suitable habitats, as towards the southern reaches of Iran the steppe is replaced by dessert vegetation even in the mountains, and in the East and on the Anatolian plateau the environment gets maybe too dry for these Astagalus species. However, a formal biogeographic analysis has to await results from genome-wide single-nucleotide polymorphisms that should result in a better resolved phylogenetic tree in comparison to the markers used here.

Material and Methods

Taxon sampling

We sampled leaf material for DNA analyses from all species of sect. Hymenostegis derived from herbarium vouchers, including most of the type specimens, as well as materials collected during fieldwork. Thus, we checked all relevant collections of the herbaria AKSU, ANK, B, FAR, GAZI, HUI, M, MSB, TARI, W, and WU. All together we included 303 individuals representing 89 species of sect. Hymenostegis and 14 species of other sections including ten species from the closely related and spiny sections. These are A. vaginans (sect. Hymenocoleus), A. submitis (sect. Anthylloidei), A. tricholobus (sect. Campylanthus), A. callistachys (sect. Microphysa), A. campylanthus (sect. Campylanthus), A. cephalanthus (sect. Microphysa), A. glaucacanthos (sect. Poterion), A. murinus (sect. Anthylloidei), A. fasciculifolius (sect. Poterion) and A. leucargyreus (sect. Adiaspastus). Another four species represent sections not closely related to the taxon under study. These are A. askius (sect. Incani), A. asterias (sect. Sesamei), A. annularis (sect. Annulares) and A. epiglottis (sect. Epiglottis). Also, two species of Oxytropis (O. karjaginii and O. kotschyana) and Biserrula pelecinus were included as outgroup taxa (but see below, 2.4). The herbarium specimens we used were up to 180 years old. Depending on storage conditions of the vouchers they were in diverse states of conservation, resulting also in rather diverse quality of extracted DNA. Therefore, not for all specimens both marker regions could be obtained. We complemented our datasets with sequences downloaded from the GenBank nucleotide database. Finally, we were able to include ITS sequences for 303 individuals representing 89 Hymenostegis species (some recognized as new taxa and up to now not formally described) plus 17 non-Hymenostegis taxa in our analysis. For the chloroplast ycf1 dataset we included 65 individuals representing 54 sect. Hymenostegis species plus ten outgroup taxa. Taxa, origin and GenBank sequence accession numbers for materials in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1 (all tables indicated by “S” are available as supplementary materials).

DNA extraction, amplification and sequencing

Total genomic DNA was extracted from about 10 mg of herbarium or silica-gel dried material with the DNeasy Plant DNA Extraction Kit (Qiagen) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. DNA concentration and quality were afterwards checked on 0.8% agarose gels. The ITS region (ITS1, 5.8 S rDNA, ITS2) was amplified using the primers ITS-A and ITS-B56. ITS1 and ITS2 were amplified separately when DNAs from very old herbarium sheets were used; in these cases, the primers ITS-C and ITS-D56 together with the primers ITS-A and ITS-B, were used. PCR was performed with 1.5 U Taq DNA Polymerase (Qiagen) in the supplied reaction buffer, 0.2 μM of each dNTP, 50 pmol of each primer, Q-Solution (Qiagen) with a final concentration of 20%, and about 20 ng of total DNA in 50 μl reaction volume in a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Perkin–Elmer). Amplification was performed with 3 min initial denaturation at 95 °C and 35 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 45 s at 56 °C and 30 s at 70 °C, followed by a final extension for 8 min at 70 °C. PCR products were purified using NucleoFast 96 PCR plates (Macherey-Nagel) following the manufacturer’s protocol, and eluted in 30 μl water. Both strands of the PCR products were directly sequenced with Applied Biosystems BigDye-Terminator technology on an ABI 3730xl automatic DNA sequencer using the primers from PCR amplifications. Forward and reverse sequences from each directly sequenced amplicon were inspected, manually edited where necessary in Chromas Lite 2.1 (Technelysium Pty Ltd), and assembled in single sequences.

To obtain sequence information from the chloroplast genome we sequenced the ycf1 gene. PCR amplification and sequencing followed Bartha et al.38. When due to low DNA quality not the entire gene region could be amplified by a single PCR, we used internal primers to amplify the locus in two separate parts. All primer sequences are provided in Supplementary Table S2. Forward and reverse sequences from each amplicon were inspected, manually edited where necessary in Chromas, and assembled in single sequences.

Sequence alignments and phylogenetic analyses

ITS and ycf1 sequences were manually aligned. We assembled four different datasets: (i) including all ITS sequences from the 303 individuals available to us (named ITS_303); (ii) a second ITS dataset were we restricted the sample design to include one individual per species resulting in 106 sequences (ITS_106); (iii) a set of 65 sequences for the chloroplast gene ycf1; (iv) and a dataset derived from 65 individuals where ycf1 and ITS sequences could be obtained. To test different models of sequence evolution Paup* 4.0a15057 was used. The Bayesian information criterion (BIC) chose the K80 + G model for the ITS datasets with one individual per species (ITS_106), whereas the Akaike information criterion (AICc) resulted in the SYM + G model. For the larger ITS dataset with multiple individuals for most Hymenostegis species (ITS_303) the respective models were JC (AICc) and TrNef + G (BIC). For the ycf1 dataset the model of sequence evolution was inferred as TVM + G (BIC, AICc), while for the ITS sequences, which were combined with the ycf1 data the models were TrNef + G (AICc) and HKY + G (BIC). In the cases were different models were inferred by AICc and BIC separate phylogenetic analyses were conducted and the trees were compared afterwards.

Potential conflict between the ITS and ycf1 loci was tested prior to combination by the partition-homogeneity test (ILD; 58) in Paup*. This test was implemented with 100 replicates, using a heuristic search option with simple addition of taxa, TBR branch swapping and MaxTrees set to 1000.

Bayesian phylogenetic inference (BI) was conducted in MrBayes 3.2.659. In BI two times four chains were run for 20 million generations for all datasets specifying the respective model of sequence evolution. In all analyses we sampled a tree every 1000 generations. Converging log-likelihoods, potential scale reduction factors for each parameter and inspection of tabulated model parameters in MrBayes suggested that stationary had been reached in all analyses. The first 25% of trees of each run were discarded as burn-in.

For all datasets also parsimony analyses were conducted in Paup* using a two-step heuristic search as described in Blattner34 for the ITS_303 dataset, including all 303 individuals, with the searches restricted to a maximum number of 10,000 trees. Heuristic searches with 25 random-addition-sequences were conducted for ITS_106, including one individual per species. Here as well a for ycf1 and the combined ITS + ycf1 datasets no maximum tree number restrictions were imposed. To test clade support bootstrap analyses were run on all datasets with re-sampling the large ITS_303 dataset 250 times, all other datasets 500 times with the same settings as before, except that we did not use random-addition sequences. Maximum-likelihood analyses of the ITS and combined ITS + ycf1 datasets were conducted in RAxML 60 using the GTRGAMMA setting and 500 bootstrap re-samples to estimate branch support values.

Divergence time estimations

To roughly estimate clade ages and divergence times within the analyzed taxa, we used a crown-group age of 12.4 My, given by Wojciechowski32, as secondary calibration point for Astragalus including Biserrula pelecinus. We used Beast 2.4.361 to analyze the dataset of ITS sequences (ITS_106) with K80 + G as model of sequence evolution, a random local clock62, and the calibrated Yule prior63,64. The node age was defined as a normal-distributed prior (12.4 ± 1.45 My, 95% distribution interval). Monophyly was enforced for the Astragalus clade including Biserrula pelecinus, as this taxon according to Wojciechowski32, Podlech and Zarre7 and also the results of our study falls into Astragalus. Three independent analyses were run for 20 million generations each, sampling every 1000 generations. Effective sample size (ESS) and convergence of the analyses were assessed using Tracer 1.6 (part of the Beast package). Appropriate burn-ins were estimated from each trace file, discarded and all analyses were combined with LogCombiner (part of the Beast package). A maximum clade credibility (MCC) tree was summarized with TreeAnnotator (part of the Beast package) using the option “Common Ancestor heights” for the nodes.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This study was carried out with financial support of the University of Isfahan and Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research (IPK). We would like to thank the authorities of the herbaria of AKSU, ANK, B, FAR, GAZI, HUI, JE, M, MSB, TARI, W and WU for providing herbarium facilities and also allowing us using plant material for DNA extraction. We also thank P. Oswald for expert technical help in the lab.

Author Contributions

A.B., A.A.M., M.R.R. and F.R.B. designed the study; A.B. and A.A.M. collected the samples; A.B., J.B. and F.R.B. performed all the experiments and statistical analyses; A.B. and F.R.B. wrote the paper; all authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version for publication.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-14614-3.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lock, J. & Simpson, K. Legumes of West Asia, a Check-List. (Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, 1991).

- 2.Wojciechowski MF, Sanderson MJ, Hu JM. Evidence on the monophyly of Astragalus (Fabaceae) and its major subgroups based on nuclear ribosomal DNA ITS and chloroplast DNA trnL intron data. Syst. Bot. 1999;24:409–437. doi: 10.2307/2419698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wojciechowski, M. F., Sanderson, M. J, Steele, K. P. & Liston, A. Molecular phylogeny of the “temperate herbaceous tribes” of papilionoid legumes: a supertree approach. Advances in Legume Systematics9, 277–298 (Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, 2000).

- 4.Maassoumi, A. A. Old World Check-List of Astragalus. (Research Institute of Forests and Rangelands, Tehran, 1998).

- 5.Lewis, G., Schrire, B., Mackinder, B. & Lock, M. Legumes of the World. (Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, 2005).

- 6.Mabberley, D. J. The Plant-Book: A Portable Dictionary of Plants, their Classification and Uses, third ed. (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2008).

- 7.Podlech, D. & Zarre, S. A Taxonomic Revision of the Genus Astragalus L. (Leguminosae) in the Old World, vols. 1–3. (NaturhistorischesMuseum, Wien, 2013).

- 8.Lavin M, Doyle JJ, Palmer JD. Evolutionary significance of the loss of the chloroplast-DNA inverted repeat in the Leguminosae subfamily Papilionoideae. Evolution. 1990;44:390–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1990.tb05207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liston, A. Use of the polymerase chain reaction to survey for the loss of the inverted repeat in the legume chloroplast genome, (eds Crisp, M. D., Doyle, J. J.), Advances in Legume Systematics, part 7. Phylogeny. (Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, pp 31–40 1995).

- 10.Wojciechowski MF, Lavin M, Sanderson MJ. A phylogeny of legumes (Leguminosae) based on analysis of the plastid matK gene resolves many well-supported subclades within the family. Am. J. Bot. 2004;91:1846–1862. doi: 10.3732/ajb.91.11.1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanderson MJ, Wojciechowski MF. Diversification rates in a temperate legume clade: Are there “so many species” of Astragalus (Fabaceae)? Am. J. Bot. 1996;83:1488–1502. doi: 10.2307/2446103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider, H. et al. Key innovations versus key opportunities: Identifying causes of rapid radiation in derived ferns (ed. Glaubrecht, M.) Evolution in Action. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 61–75 (2010).

- 13.Hodges SA, Arnold ML. Spurring plant diversification: Are floral nectar spurs a key innovation? Proc. Royal Soc. London B. 1995;262:343–348. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1995.0215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schluter, D. The Ecology of Rapid Radiations. (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 2000).

- 15.Blattner, F. R., Pleines, T. & Jakob, S. S. Rapid radiation in the barley genus Hordeum (Poaceae) during thePleistocene in the Americas(ed. Glaubrecht, M.) Evolution in Action. Springer, Heidelberg, pp. 17–33 (2010).

- 16.Bunge A. Generis Astragali species Gerontogeae. Pars prior. Claves diagnosticae. Mém. Acad. Imp. Sci. St. Petersbourg ser. VII. 1868;11:1–140. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bunge A. Generis Astragali species Gerontogeae. Pars altera. Speciarum enumeratio. Mém. Acad. Imp. Sci. St. Petersbourg ser. VII. 1869;15:1–245. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Podlech D. Die Typifizierung der altweltlichen Sektionen der Gattung Astragalus L. (Leguminosae) Mitteil. Bot. Staatssammlung München. 1990;29:461–494. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rechinger KH, Dulfer H, Patzak A. Širjaevii fragmenta Astragalogica V-VII. sect. Hymenostegis. Sitzungsberichte. Abteilung II. Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Klasse. Mathematische, Physikalische und Technische Wissenschaften. Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. 1959;168(2):7–115. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maassoumi, A. A. The Genus Astragalus in Iran, Perennials, vol. 3. (Research Institute of Forests and Rangelands, Tehran, 1995).

- 21.Zarre S, Podlech D. Taxonomic revision of Astragalus L. sect. Hymenostegis Bunge (Leguminosae) Sendtnera. 1996;3:255–312. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Podlech, D. & Maassoumi, A. A. Astragalus sect. Hymenostegis Bunge, (ed. Rechinger, K. H.), Flora Iranica, Papilionaceae IV, Astragalus II, No. 175. Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, Graz, pp 127–183 (2001).

- 23.Bagheri A, Maassoumi AA, Ghahremaninejad F. Additions to Astragalus sect. Hymenostegis (Fabaceae) in Iran. Iran. J. Bot. 2011;17:15–19. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bagheri A, Rahiminejad MR, Maassoumi AA. A new species of the genus Astragalus (Leguminosae-Papilionoideae) from Iran. Phytotaxa. 2014;178:38–42. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.178.1.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bagheri A, Rahiminejad MR, Maassoumi AA. Astragalus hakkianus a new species of Astragalus (Fabaceae) from N.W. Iran. Feddes Repert. 2013;124:46–49. doi: 10.1002/fedr.201400003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bagheri A, Karaman Erkul S, Maassoumi AA, Rahiminejad MR, Blattner FR. Astragalus trifoliastrum (Fabaceae), a revived species for the flora of Turkey. Nord. J. Bot. 2015;33:532–539. doi: 10.1111/njb.00831. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bagheri A, Maassoumi AA, Rahiminejad MR, Blattner FR. Molecular phylogeny and morphological analysis support a new species and new synonymy in Iranian Astragalus (Leguminosae) PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0149726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bagheri, A., Ghahremaninejad, F., Maassoumi, A. A., Rahiminejad, M. R. & Blattner, F. R. Nine new species of the species-rich genus Astragalus L. (Leguminosae). Novon in press (2017).

- 29.Kazempour Osaloo S, Maassoumi AA, Murakami N. Molecular systematic of the genus Astragalus L. (Fabaceae): Phylogenetic analyses of nuclear ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacers and chloroplast gene ndhF sequences. Plant Syst. Evol. 2003;242:1–32. doi: 10.1007/s00606-003-0014-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kazempour Osaloo S, Maassoumi AA, Murakami N. Molecular systematics of the Old World Astragalus (Fabaceae) as inferred from nrDNA ITS sequence data. Brittonia. 2005;57:367–381. doi: 10.1663/0007-196X(2005)057[0367:MSOTOW]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naderi Safar K, Kazempour Osaloo S, Maassoumi AA, Zarre S. Molecular phylogeny of Astragalus section Anthylloidei (Fabaceae) inferred from nrDNA ITS and plastidrpl32-trnL sequence data. Turk. J. Bot. 2014;38:637–652. doi: 10.3906/bot-1308-44. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wojciechowski MF. Astragalus (Fabaceae): A molecular phylogenetic perspective. Brittonia. 2005;57:382–396. doi: 10.1663/0007-196X(2005)057[0382:AFAMPP]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Álvarez I, Wendel JF. Ribosomal ITS sequences and plant phylogenetic inference. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2003;29:417–434. doi: 10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blattner FR. Phylogeny of Hordeum (Poaceae) as inferred by nuclear rDNA ITS sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2004;33:289–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brassac J, Blattner FR. Species level phylogeny and polyploid relationships in Hordeum (Poaceae) inferred by next-generation sequencing and in silico cloning of multiple nuclear loci. Syst. Biol. 2015;64:792–808. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syv035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blattner FR. TOPO6: A nuclear single-copy gene for plant phylogenetic inference. Plant Syst. Evol. 2016;302:239–244. doi: 10.1007/s00606-015-1259-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maassoumi, A. A. Flora of Iran, Papilionaceae (Astragalus II), no. 77. (Research Institute of Forests and Rangeland, Tehran, 2014).

- 38.Bartha L, Dragoş N, Molnár AV, Sramkó G. Molecular evidence for reticulate speciation in Astragalus (Fabaceae) as revealed by a case study from section. Dissitiflori. Botany. 2013;91:702–714. doi: 10.1139/cjb-2013-0036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pleines T, Blattner FR. Phylogeographic implications of an AFLP phylogeny of the American diploid Hordeum species (Poaceae: Triticeae) Taxon. 2008;57:875–881. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eaton DAR, Ree RH. Inferring phylogeny and introgression using RADseq data: An example from flowering plants (Pedicularis: Orobanchaceae) Syst. Biol. 2013;62:689–706. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syt032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones RC, Nicolle D, Steane DA, Vaillancourt RE, Potts BM. High density, genome-wide markers and intra-specific replication yield an unprecedented phylogenetic reconstruction of a globally significant, speciose lineage of Eucalyptus. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2016;105:63–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mitchell AD, Heenan PB. Sophora sect. Edwardsia (Fabaceae): Further evidence from nrDNA sequence data of a recent and rapid radiation around the Southern Oceans. Bot. J. Linnean Soc. 2002;140:435–441. doi: 10.1046/j.1095-8339.2002.00101.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Catalano SA, Vilardi JC, Tosto D, Saidman BO. Molecular phylogeny and diversification history of Prosopis (Fabaceae: Mimosoideae) Biol. J. Linnean Soc. 2008;93:621–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2007.00907.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Egan AN, Crandall KA. Divergence and diversification in North American Psoraleeae (Fabaceae) due to climate change. BMC Biol. 2008;6:55. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-6-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Drummond CS, Eastwood RJ, Miotto STS, Hughes CE. Multiple continental radiations and correlates of diversification in Lupinus (Leguminosae): Testing for key innovations with incomplete taxon sampling. Syst. Biol. 2012;61:443–460. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syr126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nürk NM, Uribe-Convers S, Gehrke B, Tank DC, Blattner FR. Oligocene niche shift, Miocene diversification – Cold tolerance and accelerated speciation rates in the St. John’s Worts (Hypericum, Hypericaceae) BMC Evol. Biol. 2015;15:80. doi: 10.1186/s12862-015-0359-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lagomarsino LP, Condamine FL, Antonelli A, Mulch A, Davis CC. The abiotic and biotic drivers of rapid diversification in Andean bellflowers (Campanulaceae) New Phytol. 2016;210:1430–1442. doi: 10.1111/nph.13920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frenzel B. The Pleistocene vegetation of northern Eurasia. Science. 1968;161:637–649. doi: 10.1126/science.161.3842.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tarasov PE, Volkova VS, Webb T, et al. Last glacial maximum biomes reconstructed from pollen and plant macrofossil data from northern Eurasia. J. Biogeography. 2000;27:609–620. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2699.2000.00429.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Franzke A, et al. Molecular signals for Late Tertiary/Early Quaternary range splits of an Eurasian steppe plant: Clausia aprica (Brassicaceae) Mol. Ecol. 2004;13:2789–2795. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Friesen N, et al. Dated phylogenies and historical biogeography of Dontostemon and Clausia (Brassicaceae) mirror the palaeogeographical history of the Eurasian steppe. J. Biogeography. 2016;43:738–749. doi: 10.1111/jbi.12658. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hewitt GM. Some genetic consequences of ice ages, and their role in divergence and speciation. Biol. J. Linnean Soc. 1996;58:247–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.1996.tb01434.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roy K, Valentine JW, Jablonski D, Kidwell M. Scales of climatic variability and time averaging in Pleistocene biotas: Implications for ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1996;11:458–463. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(96)10054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jakob SS, Ihlow A, Blattner FR. Combined ecological niche modeling and molecular phylogeography revealed the evolutionary history of Hordeum marinum (Poaceae) – niche differentiation, loss of genetic diversity, and speciation in Mediterranean Quaternary refugia. Mol. Ecol. 2007;16:1713–1727. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ikeda H, Carlsen T, Fujii N, Brochmann C, Setoguchi H. Pleistocene climatic oscillations and speciation history of an alpine endemic and a widespread arctic-alpine plant. New Phytol. 2012;194:583–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blattner FR. Direct amplification of the entire ITS region from poorly preserved plant material using recombinant PCR. Biotechniques. 1999;29:1180–1186. doi: 10.2144/99276st04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Swofford, D. L. PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (* and other methods). Version 4.0a150. (Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, 2002).

- 58.Farris JS, Kallersjo M, Kluge AG, Bult C. Testing the significance of incongruence. Cladistics. 1994;10:315–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.1994.tb00181.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ronquist F, et al. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stamatakis A. RAxML Version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bouckaert RR, et al. BEAST 2: A software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014;10:e1003537. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Drummond AJ, Suchard MA. Bayesian random local clocks, or one rate to rule them all. BMC Biology. 2010;8:114. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heled J, Drummond AJ. Calibrated tree priors for relaxed phylogenetics and divergence time estimation. Syst. Biol. 2012;61:138–149. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syr087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bartha L, Sramkó G, Dragoş N. New PCR primers for partialycf1 amplification in Astragalus (Fabaceae): Promising source for genus-wide phylogenies. Studia UBB Biologia. 2012;51:33–46. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hijmans, R. J. et al. DIVA-GIS, Version 5: A geographic information system for the analysis of biodiversity data [Software]. International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI) Available from: http://diva-gis.org. (2005).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.