Abstract

Reef-building corals have essential roles in reef ecosystems but are highly susceptible to disturbances. Increasing anthropogenic disturbances are eroding coral community resilience, leading to declining reef ecosystem function and status globally. Successful reproduction and recruitment are essential for restoring coral populations but recruitment-limitation can constrain recovery. We supplied ~400,000 Acropora tenuis larvae in fine-mesh enclosures on each of four larval-enhancement plots, comprising natural reef substrata and ten settlement tiles, on degraded reef areas in the northwestern Philippines. Initial mean total settlement on tiles in larval-enhancement plots was high (255.3 ± 68.6), whereas no larvae settled in natural control plots. Recruit survivorship began stabilising after five months, with juveniles becoming visible by eye at nine months. After three years a mean of 2.3 m−2 colonies survived within each larval-enhancement plot. Most colonies grew rapidly (16.1 ± 0.7 cm mean diameter) and spawned successfully at three years, thereby quickly re-establishing a breeding population. In contrast, natural recruitment failed to produce any new visible A. tenuis colonies. These results demonstrate that mass larval settlement can rapidly enhance recruitment and coral recovery on degraded reef areas, and provides an important option for active reef restoration where larval supply and recruitment success are limiting.

Introduction

Coral reefs are facing intensifying anthropogenic impacts1–3 resulting in reef-building coral populations and live coral cover declining in many reef regions4–6. More than 60 percent of the world’s coral reefs are degraded or seriously threatened with loss in coming decades2,7. Human threats to coral reefs are particularly severe in the Coral Triangle region that encompasses the global center of marine biodiversity8. It is estimated that nearly 95 percent of coral reefs in the Southeast Asia region are threatened by human activities and about 50 percent of these reefs are in the high or very high threat categories, with Indonesia and the Philippines having the largest areas of threatened reefs7. Reef degradation directly threatens the extraordinary biodiversity and immense ecological and socio-economic values of reefs that support many millions of people7,9. Although it is not currently feasible to restore all degraded reefs, mitigating the causes of degradation and initiating restoration of corals on reefs that can be managed are becoming increasingly urgent.

Successful reproduction and recruitment are critical for the maintenance and recovery of scleractinian coral species and underpin reef resilience10,11. However, ongoing declines in coral abundance and reproductive biomass can lead to loss of breeding colonies and decreasing reproductive success (critical depensation) resulting in recruitment limitation or failure12–14.

Active coral restoration can enhance coral cover and abundance, but current restoration methods have not yet been effective at larger scales needed to halt or reverse the decline in reef coral communities15,16. Most coral restoration studies have used smaller-scale asexual fragmentation of adult colonies in combination with various transplantation and nursery techniques, but these are relatively labour-intensive and expensive17,18. Fragmentation damages donor colonies and increases disease risk, and most coral fragmentation studies have used fragments with limited genetic diversity which constrains their resistance to future stress disturbances16,18,19. Alternatively, mass larval enhancement using millions of sexually-derived larvae resulting from large-scale spawning events of highly fecund corals20,21 has strong potential for scaling-up restoration efforts to larger reefal scales10. Mass larval enhancement also has significant advantages of providing greater genotypic diversity among recruits that is likely to improve adaptive and evolutionary potential22 and increase resistance to future disturbances23, thereby strengthening reef community resilience and recovery rates.

To date, results from only two small-scale in situ field trials using mass coral larval settlement have been published, and both studies used reef areas adjacent to healthy coral communities in Marine Protected Areas24,25. Heyward et al.24 used Acropora larvae sampled from coral spawn slicks and reared in small 1.8 m floating culture ponds to ‘seed’ small 1.8 × 1 m reef areas at Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia24. After four weeks more than 6,500 acroporid coral recruits were growing on conditioned terracotta tiles in the larval ‘seeded’ areas, whereas settlement on control tiles and natural recruitment rates were up to 100-fold lower24. However, subsequent survival or growth of the recruits was not monitored. Hence, longer-term recruitment outcomes from this study were not determined. In Palau, ~1 million ex situ cultured Acropora digitifera larvae were used to ‘seed’ replicate concrete pallet balls for 24 hours resulting in significantly higher acroporid recruitment on fibre-cement tiles attached to ‘seeded’ pallet balls compared with unseeded control tiles after 5 weeks25. Monitoring after 30 weeks and ~13 months showed no significant differences in acroporid recruit densities between ‘seeded’ and control treatments due to high post-settlement mortality of A. digitifera recruits and high rates of natural acroporid coral recruitment in this healthy reef system25.

Here, we evaluate for the first time the longer-term effects of mass coral larval settlement directly on degraded reef areas in the northwestern Philippines where coral cover is low and natural recruitment is severely limited. Specifically, we demonstrate the effectiveness of using mass larval enhancement to initiate coral recovery by monitoring settlement, survival, growth and onset of sexual reproduction of Acropora tenuis recruits on coral recruitment tiles and natural reef substrata for three years.

Methods

Experimental Design

This experiment was designed to test the effect of supplying large numbers of coral larvae on replicate degraded reef areas during a five-day larval settlement period to quantify initial larval settlement and longer-term recruitment outcomes. Long-term monitoring over three years enabled subsequent patterns of post-settlement survival, growth and onset of sexual reproduction of coral recruits in larval enhanced plots versus control plots without larval provision to be compared.

Site selection and reef benthic community status

Prior to the larval enhancement experiment, degraded reef areas at 3–4 m depth were identified at the Magsaysay reef in the Lingayen Gulf, Anda, Pangasinan, Northern Luzon, Philippines (16°19’36” N, 120°02’01” E; Fig. 1). Relatively high 30–50% coral cover was recorded in surveys on reefs in the Bolinao-Anda Reef Complex (BARC), Pangasinan, up to 198126. However, reef status and water quality in the Lingayen Gulf have been declining since the early 1980s, coinciding with increased fishing pressure including destructive blast fishing, and aquaculture development27. Live coral cover on reefs in Bolinao declined from about 41% mean cover in the late 1908s to less than 22% mean cover by 199927. The coral community28 in the Magsaysay reef area was subsequently severely impacted by a Crown-of-thorns starfish outbreak in 2007 (DWdC, pers. obs.) and previous extensive blast fishing which no longer occurs27. For the present study, a total of eight 6 × 4 m reef plots (about 2–4 m apart) were haphazardly selected on the reef and demarcated using steel bars. Four randomly selected plots were treated with larvae (larval-enhanced) and the other four plots were controls – without provision of larvae. Prior to the larval enhancement experiment, photographs of the benthic communities within each plot were taken using a 1 × 1 m frame and analysed using CPCe29 to quantify benthic cover of corals and other benthos and to determine the reef community status in the area. A total of 10 random points were generated and the benthic category underlying each point was scored in each of the 24 frames taken in each of the plots. There were no A. tenuis adult colonies or visible recruits from previous spawning events present inside the plots prior to the larval enhancement activity.

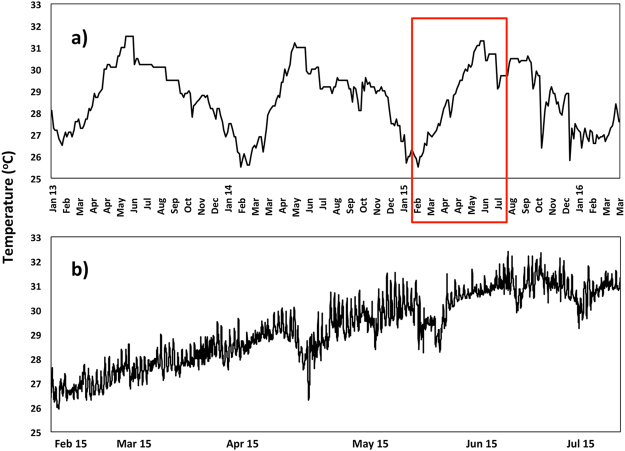

Figure 1.

Locations of the experimental larval-enhanced and control plots (Magsaysay Reef) and the source of A. tenuis colonies (Caniogan Reef) in the Bolinao-Anda Reef Complex, northwestern Philippines. (Figure created with Adobe Illustrator CS6 http://www.adobe.com/uk/products/illustrator.html).

Settlement tiles

Ten biologically conditioned 10 × 10 cm natural coral settlement and recruitment tiles cut from dead table Acropora with varying thickness (about 3–4 cm average) were deployed inside each of the eight plots just prior to the larval enhancement experiment to quantify the initial settlement rates of the A. tenuis larvae. Each tile was identified with a coded tag, and was attached onto a stainless steel post projecting from a base plate attached to the reef, with a 0.5 cm gap above the base plate to enable larval settlement on all surfaces30. Dead table Acropora pieces used to produce the tiles were collected from the intertidal zone beside Cory reef rubble bar near the experimental site (Fig. 1). The tiles were conditioned for a month in aquaculture tanks with flow-through seawater and aeration at the Bolinao Marine Laboratory (BML) of The Marine Science Institute (University of the Philippines) prior to use on the reef plots, and were examined to ensure no coral recruits were present prior to their use.

To estimate the total surface area of the irregular surfaces of the tiles, 30 representative tiles were 3D scanned using a David® SLS-1 structured white light technology scanning system. The scanner had a mesh density up to 1,200,000 vertices per scan with resolution precision up to 0.1% of scan size down to 0.06 mm. Each tile was scanned and shot in all angles using a 360° turntable and each shot was fused to form a digitised 3D object. The formed 3D object was then converted to a stereolithography (STL) file that was further refined using 3D modelling software (viz., Zbruzh™ and Blender™). The surface area of the 3D image of the tiles was analysed and calculated using netFabb® software. As there was minimal variation in the surface area of the scanned tiles (mean: 360 ± 3.7 SE cm2), larval settlement and recruitment was expressed as numbers of recruits per tile.

Coral collection and larval culture

Thirty gravid colonies of Acropora tenuis (minimum diameter of 15–20 cm) were collected from the reef ~2–4 m deep in Caniogan, Anda, Pangasinan (Fig. 1; 16°19’36” N, 120°02’01” E) a week before the full moon of April 2013. This species was selected for this study because it is relatively common in the Bolinao-Anda Reef Complex in the northwestern Philippines, and larvae from this species have been successfully cultured in previous experiments31–33. Furthermore, Acropora tenuis was chosen for this study as it has a well-defined and characteristic morphology that enables colonies to be readily identified and distinguished from other species underwater34 thereby enabling early detection, identification and monitoring of recruits resulting from larval settlement. Prior to collection, colonies were sampled by carefully breaking a few branches to determine the presence of mature oocytes, as indicated by their pink colouration35. Gravid colonies were carefully transported in seawater to the BML aquaculture facility for ex situ spawning and gamete collection.

Colonies were maintained in a healthy condition in concrete tanks with flow-through seawater and aeration and were monitored periodically at night to check for setting and spawning behaviours20,36,37. Gametes from major spawning events involving 30 colonies that spawned between 1830 and 1900 h on April 29 and 30 2013 (3 and 4 nights after full moon, respectively) were collected for use in this experiment. Gamete collection and larval culture followed standard methods with minor modifications16,38–40.

Many thousands of spawned egg-sperm bundles were skimmed off the water surface and transferred to a fertilization container in 10 L of 1 µm filtered seawater. Gamete bundles were gently agitated to facilitate egg and sperm separation and to maximize subsequent cross-fertilization41. After 1 hour, seawater containing excess sperm was siphoned off (sperm-washing) beneath the floating eggs and new filtered seawater was slowly added. This process was repeated three times to remove excess sperm that may degrade water quality during larval culture and to prevent polyspermy41. Subsamples of embryos and eggs were collected and examined after a further hour under a stereomicroscope to determine percentage fertilization.

Developing embryos were transferred into 13 large rearing tanks (each containing >1,000 L of seawater) at water surface densities between 4–5 embryos cm−2 for 24 h. To maintain embryos and larvae in a healthy condition, aeration was supplied 24 h after fertilization and 50 L of new filtered seawater was added daily to tanks with developing larvae. Spawned coral colonies were returned in a healthy condition and reattached onto the reef using underwater adhesive (a mixture of cement and epoxy).

At 4 d post-fertilization, competent actively swimming larvae were collected using a plankton net sieve (60 µm mesh size) and transferred to a holding basin. The total number of larvae was estimated using three replicate 60 ml sub-samples taken from the basin after the larvae had been concentrated and thoroughly mixed throughout the water column to distribute them evenly, and then the larvae were distributed equally into twelve strong 40 × 50 cm 20 L plastic bags. Oxygen was supplied into each bag before it was sealed for transport to the field for the larval enhancement experiment at Magsaysay reef.

Coral larval enhancement

Organza-hapa mesh enclosures were used to retain the larvae inside the four larval enhancement plots during the 5-day larval settlement period. The organza cloth (100–150 µm mesh opening) was sewn to form 6 × 4 m enclosures, with hapa nylon net (500 µm mesh) as a second, outer layer for additional support. This mesh enclosure assembly can effectively retain A. tenuis larvae whose diameters are 300–500 µm42. Cylindrical 20 g weights (1.75 × 4 cm) were inserted along the lower edge of the mesh to firmly hold the mesh enclosure in place on the reef and prevent larvae from escaping during the settlement period. The mesh enclosures covered the top and sides of each site and extended up to 75 cm from the reef with the bottom open to the reef to enable larvae to settle, and the corners were secured using steel reinforcing bars driven into the substratum. An estimated 410,670 ± 26,354 larvae were introduced into the mesh enclosure on each of the four larval-enhanced plots through re-sealable openings distributed over the upper areas of the mesh enclosures. Control plots were also covered by organza-hapa mesh enclosures during this period but no larvae were introduced. All living corals inside the plots (between 10 – 30 colonies up to 80 cm diameter per plot) were carefully covered with thin plastic mesh with 1 cm mesh openings to avoid the mesh enclosures from becoming caught and ripping and damaging the coral tissues.

Five days after the provision of larvae inside the mesh enclosures, the enclosures and the protective plastic mesh around living corals were removed from all plots. All settlement tiles were then carefully collected and kept submerged in clean seawater while carefully taken to the BML laboratory to monitor the initial numbers of settled coral spat on each tile under a stereoscope while the tiles remained submerged in seawater. Each coral recruit was recorded and carefully mapped to facilitate repeated monitoring at 2, 5, 9, 12, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23, 31, 34 and 35 months after settlement. The tiles were returned immediately to their specific location and correct orientation within each experimental plot after each monitoring period. Where required, small clumps of algae were periodically removed from the tiles to avoid recruits being overgrown by algae.

Coral recruits on reef substrata

The process of larval settlement includes the initial attachment of competent larvae onto substrata and their metamorphosis into a coral polyp (spat), while recruitment refers to the subsequent life stage of the coral following post-settlement survival and growth to become new members of the population21,43. Corals are initially small and invisible cryptic recruits and subsequently grow to become larger visible colonies that are often referred to as juveniles44. Acropora tenuis recruits that had settled on natural reef substrata inside the larval-enhanced plots became visible underwater 9 months after the larval enhancement activity. The concurrent size of the juvenile A. tenuis on the recruitment tiles and their characteristic morphology were used as the basis for identification of A. tenuis juveniles on natural substrata inside the plots that originated from the larval enhancement experiment. Identified A. tenuis juveniles on the natural reef substrata were mapped and tagged with a numbered tag for growth and survivorship monitoring together with the juveniles on the recruitment tiles for 36 months after the larval enhancement. Juvenile colonies on the natural reef substrata were repeatedly monitored at 9, 12, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23, 31 and 35 months after settlement.

In situ growth monitoring commenced at this time, with the length (l), width (w) and height (h) of each of the juvenile corals on recruitment tiles and natural substrata measured using calipers. Mean planar diameter was calculated from the maximum and minimum diameters measured for each colony. The ecological volume (EV) was calculated using the volume formula: EV = πr2 h, where r = (l + w)/445.

Background coral recruitment

Background natural recruitment rates in the restoration site were monitored by deploying and replacing ten 10 × 10 cm natural Acropora coral skeleton recruitment tiles quarterly in each of the control plots for 24 months from May 2013 to May 2015. Tiles were biologically conditioned for one month in tanks with flow-through seawater and aeration at the BML aquaculture facility then carefully transported in seawater to the experimental site. Tiles were labelled and attached to individual posts in the same manner as tiles used for the larval settlement experiment, described above. The recruitment monitoring periods encompass the known coral spawning periods in Bolinao-Anda reefs from February to July, with extended planulation periods throughout the year for brooding pocilloporid and poritid coral species16,37 (DWdC and PLH, pers. obs.). Retrieved tiles were bleached in 10% sodium hypochlorite solution for at least 48 hr and then air-dried. Tiles were examined under a stereomicroscope and each coral spat recorded was categorized as acroporid, pocilloporid, poritid, others, or unidentified (for broken and damaged unidentifiable recruits) based on their skeletal morphology46.

Onset of sexual reproduction

The onset of sexual reproduction in A. tenuis colonies that recruited onto coral tiles and natural reef substratum was monitored by carefully breaking and replacing small branches to determine the presence of gametes35. Monitoring was done at age 10, 20 and 34 months prior to the predicted spawning periods after 1, 2 and 3 years of growth. After two years of growth, the A. tenuis colonies resulting from settled larvae ranged in size from 3 to 23 cm mean diameter, with an overall mean diameter of 11 (±1) cm, which was close to the minimum size threshold recorded for Acropora colonies to become sexually reproductive32,33. At 35 months the volume of all gravid and non-reproductive colonies was measured to determine the size and age of onset of sexual reproduction. At 36 months spawning of the gravid A. tenuis colonies was monitored in situ after the April 2016 full moon.

Coral production cost analysis

To estimate the cost of producing sexual coral recruits from this study on Magsaysay reef we used the methods outlined in Edwards16. The costs were categorised and then summed for all materials and infrastructure, boat hire and fuel, diving and labour for gravid coral collection (using different wage rates for different skill levels), spawning and larval rearing, site preparation and capital costs for the larval mesh enclosures (Supplementary Table S1). To estimate the cost per coral colony produced at different ages, the total cost was divided by the total numbers of juvenile corals alive at 9 months and at three years of age in the four larval enhancement plots. Costs were in Philippine Pesos and were converted to US$ (Supplementary Table S1).

Environmental parameters

Sea Surface Temperature (SST) data from 2013 to March 2016 were obtained from coralreefwatch@noaa.gov, and these data were supplemented with in situ data recorded on a Stowaway temperature data logger deployed at 3 m depth near the experimental plots from February to July 2015. Other water quality and environmental parameters were monitored periodically during the study (Supplementary Table S2). Salinity was measured with a handheld refractometer using three replicate water samples collected from the larval enhancement site in 15 ml tubes. Light intensity was measured using a LI-COR®193SA spherical quantum sensor attached to a LI-COR® LI-1400 data logger. The average of ten to fifteen consecutive light readings at noon were obtained. Sedimentation was quantified using three PVC sediment traps, each 5 cm in diameter and 20 cm in height, conforming to the 1:4 ratio recommended by Gardner (1980)47. Sediment traps were deployed for 24 h periods in the larval enhancement site. Water motion was measured using the clod card technique48. Three clod cards were deployed for 24 h per plot, and in the BML seawater aquaculture tanks. Clod cards were weighed prior to deployment and after retrieval, and the weight lost was used as an indicator of the water motion.

Statistical Analysis

Data are reported as mean values ± standard error. The four larval enhancement plots and the four control plots were used as statistical replicates (N = 4), with data from the ten tiles in each plot averaged to quantify mean initial settlement rates, and subsequent growth and number of surviving recruits at age 35 months. Analysis of similarities (ANOSIM) was performed using PRIMER v6 to test for similarities and significant differences in the percent benthic cover composition (e.g., sand, rubble, macroalgae, coral) between larval enhancement and control plots before the larval experiment. Benthic cover data did not require transformation and similarities were calculated using the Bray-Curtis similarity measure. Significant differences in the initial larval settlement patterns on different tile surfaces on tiles from the larval-enhanced plots after five days of larval settlement were tested using One-way ANOVA. Tukey’s HSD test was conducted post hoc to determine significant differences in settlement patterns among tile surfaces.

Survivorship of coral recruits on different surfaces of tiles was analysed using survival analysis, a non-parametric pairwise comparison test based on the Kaplan–Meier function49. The same analysis was used to determine any significant difference in survival patterns of juvenile corals on natural substrata and on tiles from nine to 35 months after the larval enhancement. In one case multiple recruits that had settled close to each other on the reef substratum subsequently grew together and fused to form a single colony, and this was considered as a ‘censored observation49. Significant increases in growth of juvenile corals through time were determined using Repeated Measures ANOVA. One-way ANOVA was used to compare growth rates of juvenile corals on recruitment tiles versus growth rates on natural substrata, and to compare the rates of natural recruitment of acroporids on settlement tiles in the study area versus recruitment of A. tenuis from the larval enhancement activity.

Results

Benthic cover and reef condition

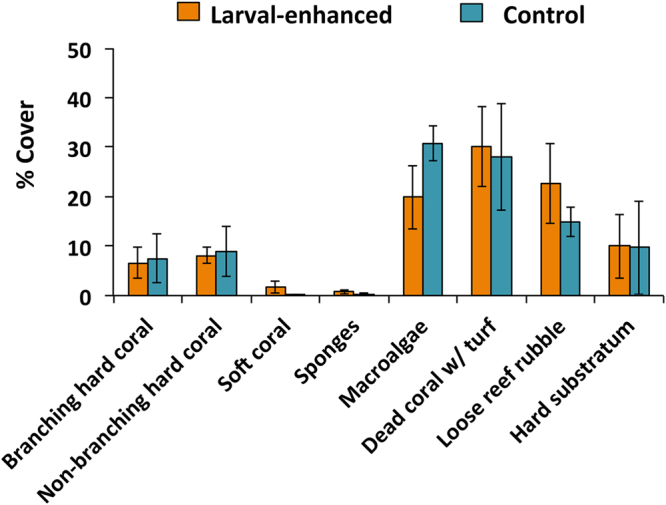

Benthic cover and reef community status at the reef site were quantified prior to the experiment and were comparable (R: 0.04, P = 0.40, ANOSIM) in the four replicate larval enhancement plots and the four control plots (Fig. 2). All plots were degraded and characterised by low mean living scleractinian coral cover of 15.6% (±1.6% SE), with soft corals, sponges, macroalgae and dead coral covered with algae comprising 56.8% (±2.9%) mean benthic cover (Fig. 2). Dead coral and coral rubble surfaces potentially available for coral larval settlement equated to 27.6% (±3.7%) of mean cover, which represents about 7 m2 of the reef area within each of the 24 m2 plots (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Mean percentage cover of benthic categories in larval-enhanced (N = 4) and control (N = 4) plots before the experiment. Error bars are ± SE.

Larval development and initial settlement

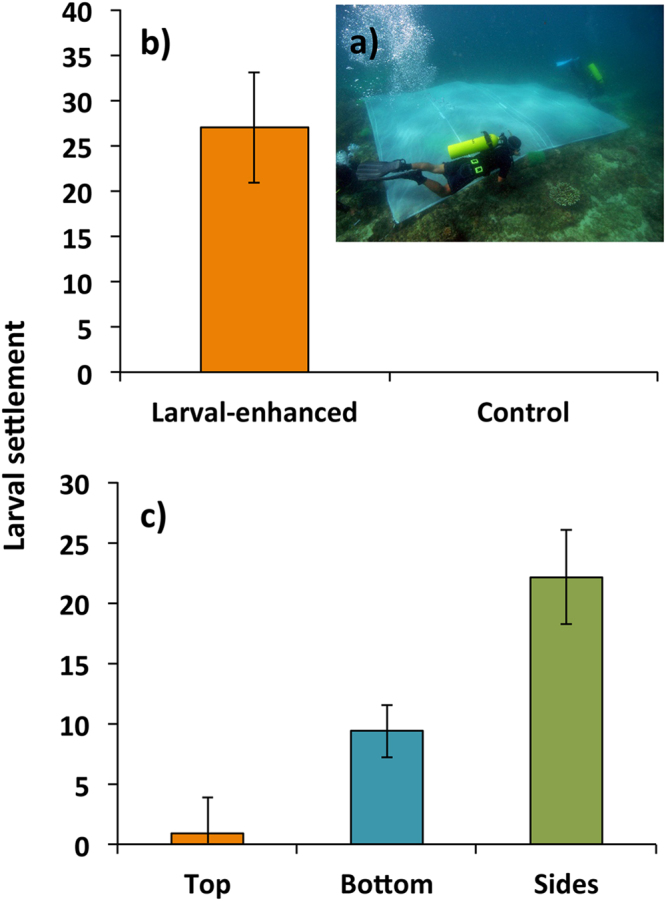

A total of 1,021 A. tenuis spat settled on the 40 10 × 10 cm (total of 14,400 cm2 tile area) biologically conditioned natural Acropora skeleton tiles that were attached to reef surfaces in the larval enhancement treatment plots (Fig. 3a) during the 5-day settlement period (Fig. 3b). Mean total settlement on the sets of ten tiles in each of the four larval enhancement treatment plots was 255.3 (±68.6) spat. This was significantly higher than for control plots in which no A. tenuis spat settled (Fig. 3b). Mean larval settlement on tiles in the larval enhancement plots was significantly higher on side surfaces of tiles compared to bottom and top surfaces (α = 0.05, Tukey’s test, Fig. 3c).

Figure 3.

(a) Larval mesh enclosure used to retain larvae on reef plots during settlement, (b) mean initial A. tenuis larval settlement on all tile surfaces in the larval-enhanced (N = 4) and control (N = 4) plots after 5 days, and (c) mean settlement on the different surfaces of tiles in the larval-enhanced plots (N = 4). Means are for ten tiles per plot and averaged among the four replicate plots. Error bars are ± SE.

Recruit survival

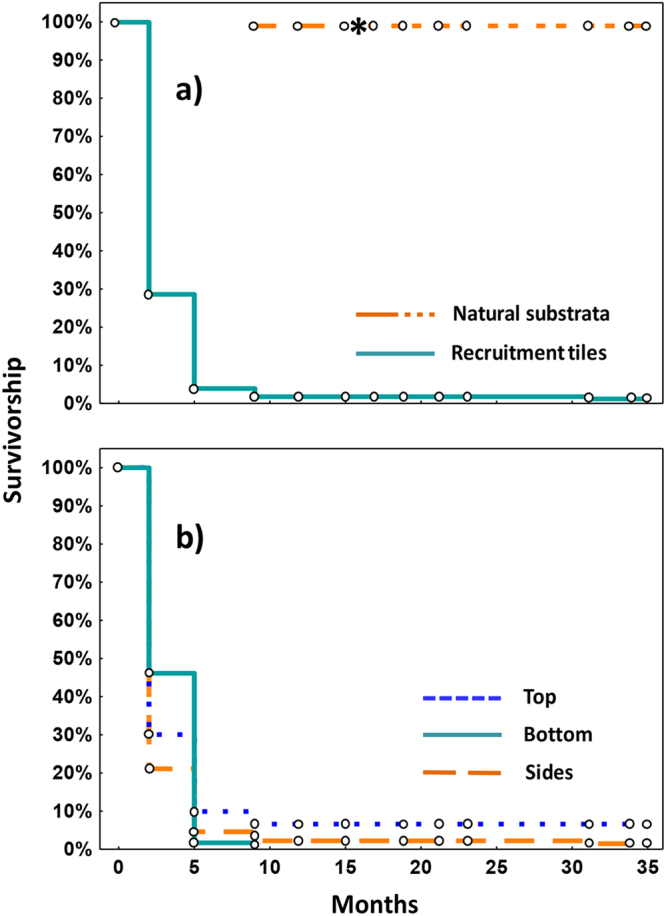

Subsequent repeated monitoring showed a steep decline in survivorship of settled juvenile corals on tiles during the first five months after settlement (Fig. 4a), corresponding to a Type III survivorship curve. Little additional mortality was recorded after five months and survivorship stabilised after nine months. This coincided with the period when the previously cryptic juveniles that had settled on the natural reef substrata became visible recruits at 2.1 (±0.4) cm mean diameter for in situ growth and survivorship monitoring (Fig. 4a). At nine months after settlement, a total of 94 A. tenuis recruits were recorded on the natural reef substrata in the four larval enhancement plots, and a total of 18 recruits survived on the settlement tiles.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survivorship over 35 months for (a) A. tenuis recruits settled on tiles (N = 1021), and for visible recruits on natural reef substrata starting at 9 months post-settlement (N = 94) where the *marks the monitoring period where 31 juvenile corals had fused to form a single colony, and (b) A. tenuis recruits on different tile surfaces (N = 1,021).

For corals that settled on the natural reef substrata, all juvenile corals remained alive from nine months to 15 months post-settlement. There were 31 individual juvenile corals that had settled close together on the reef fused to form a single coral colony between 15 and 17 months of age (Fig. 4a), hence the fused corals were treated as a ‘censored’ observation in the survival analysis. Among coral recruits that settled on the natural reef substrata no mortality was recorded from 17 to 35 months after settlement, resulting in a total of 66 colonies surviving in the larval enhancement plots after almost three years.

There was 100% survival of tagged A. tenuis settled juveniles on recruitment tiles from nine months to two years post-settlement (Fig. 4a). However subsequent monitoring in 2015 and 2016 showed that five colonies on settlement tiles died between 24 and 32 months post-settlement (Fig. 4a,b). One colony appeared partly bleached during April 2015, coinciding with increasing sea temperatures on the reef (Fig. 5a,b), and this colony was dead when monitored in December 2015. Four larger colonies on tiles were eaten by Drupella sp. gastropods in December 2015, probably just prior to that monitoring period based on the low density of turf algae growing on the recently exposed coral skeletons and the presence of Drupella on these colonies. Another large colony on a tile was partially eaten by Drupella when monitored in December 2015, so the gastropods were removed and the remaining colony branches survived and grew. In contrast, no A. tenuis colonies on the natural reef substrata were eaten by Drupella. A total of 13 colonies survived on settlement tiles after 35 months.

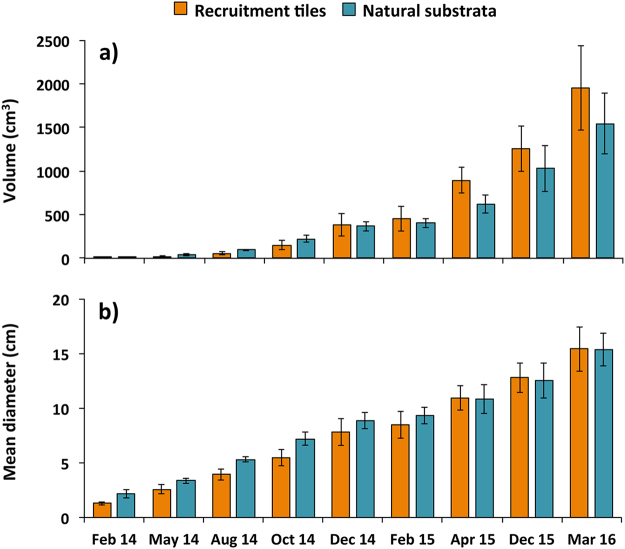

Figure 5.

(a) Sea surface temperature profile in the Bolinao region during this study from January 2013 to March 2016 (coralreefwatch@noaa.gov), and (b) temperatures recorded in situ at the Magsaysay Reef study site using a data logger from Feb 2015 to Jul 2015, corresponding to the period indicated within the red box in (a).

The patterns of high survivorship of visible recruits on the natural reef substrata and on the settlement tiles after 5 months occurred despite an anomalous increase in sea surface temperature to 32 °C and partial bleaching of some corals on nearby reef areas at 26 months after settlement (Fig. 5a,b). Survivorship of recruits on tiles from May 2013 to April 2016 (Fig. 4b) varied significantly among tile surfaces (χ² = 53.35, P = <0.01, Log-rank test; sides >bottom = top). The mean total number of surviving recruits on the ten tiles in each settlement site after 35 months was 3.3 (±1.0), which equates to 9 colonies (±2.6) per m2 of tile surface. The mean number of surviving A. tenuis colonies on the natural reef substrata in each settlement site after 35 months was 16 (±5.7), which equates to 2.3 new colonies developing from larvae on each m2 of the approximately 7 m2 of available reef substrata in each of the larval settlement plots (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Acropora tenuis colonies growing on a larval enhancement plot three years after settlement. *Indicates colonies grown from settled larvae, **indicates the large colony derived from fusion of 31 small colonies grown from settled larvae.

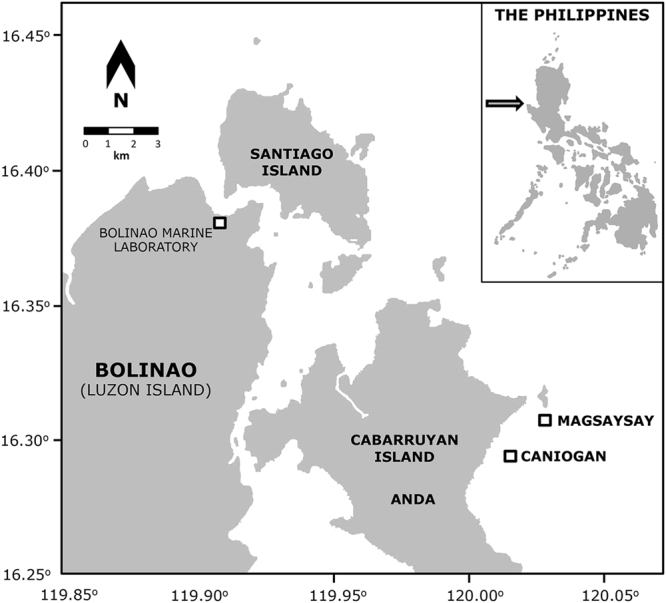

Recruit growth and onset of sexual reproduction

Average growth rates of A. tenuis recruits monitored on natural reef substrata from nine months to two years post-settlement reached 40.9 (±6.8) cm3 mo−1 and were similar (F 3,6 = 2.36, P = 0.17, ANOVA) to growth rates of recruits that settled on tiles (59.3 ± 9.8 cm3 mo−1; Fig. 7). Volumes of recruits on tiles versus natural reef substrata did not differ significantly in any of the monitoring periods (repeated measures ANOVA; Fig. 7a). For growth analysis, data on growth of the 31 recruits that fused to form one colony (Fig. 6) were excluded. The volume for this fused colony reached 19232.5 cm3 with a mean diameter of 35 cm, which was the largest colony among the recruits (Fig. 7) and eight times larger than the mean volume of all the other 78 surviving corals after 35 months.

Figure 7.

Mean volume (a) and mean diameter (b) of juvenile A. tenuis on recruitment tiles and natural substrata inside the four larval-enhanced plots (N = 4). Error bars are ± SE.

At nine months post-settlement, the 94 juvenile A. tenuis corals on natural reef substrata had a mean diameter of 2.1 ± 0.4 cm, and the 18 juvenile corals on tiles had a mean diameter of 1.3 ± 0.1 cm. From nine months to two years post-settlement, there was no mortality recorded for corals growing on natural reef substrata and on tiles, and mean diameters of two year old corals were 11.9 ± 1.0 cm and 10.9 ± 1.1 cm, respectively. After two years of growth, the A. tenuis colonies were not sexually reproductive. However, by 35 months of age colony size had increased up to 16.1 ± 0.7 cm mean diameter (Fig. 7b), and the 53 colonies that were larger than 12.5 cm mean diameter were sexually reproductive and spawned egg-sperm bundles after the April 2016 full moon. These comprised 44 reproductive colonies growing on the natural reef substrata and nine colonies on the tiles.

Production costs

The total production cost for the sexually derived A. tenuis colonies in this study was US$1654.00. This equates to a production cost of $14.77 for each of the 112 recruits alive at 9 months, and $20.94 for each of the 79 colonies surviving after 35 months (Supplementary Table S1).

Background coral recruitment

A total of 4,197 coral spat were recorded settled on 307 natural recruitment tiles deployed for three-month periods over two years. Natural juvenile coral recruitment was dominated by pocilloporids (88.5%), with very minor recruitment of acroporids (2.7%), poritids (2.3%), and other recruits (3.8%), and 2.8% of recruits were broken and damaged and therefore unidentifiable (Fig. 8). Highest recruitment was consistently found during February monitoring periods which had means of 23 ± 2.5 recruits recorded on the ten tiles per plot in 2014, and 19.9 ± 1.9 recruits in 2015. Lowest recruitment rates were found during August 2013 (2.1 ± 0.3) and August 2014 (8.7 ± 1.0). Monitoring of adult corals and new visible colony recruits at the control plots over three years showed that no new natural A. tenuis coral recruits were present. Acropora tenuis recruitment from the larval settlement experiment was significantly higher (70 times greater) than natural acroporid recruitment during any of the monitoring periods (F 8,27 = 19.20, P = <0.001, ANOVA; Tukey’s test, α < 0.05).

Figure 8.

Mean natural coral recruitment patterns on monitoring plots (N = 4) in the larval enhancement study area, recorded on ten tiles combined per site. Error bars are ± SE.

Discussion

Despite increasing coral reef research and management activity, the global crisis in reef degradation and destruction continues to worsen and the loss of reef-building coral communities is occurring at unsustainable rates in many reef regions4,7. Natural recovery of coral populations and reef communities can occur where key threats are managed and disturbance regimes do not impair recovery50 and where natural rates of larval supply lead to sufficiently high rates of recruitment to enable the re-establishment of coral communities even after severe disturbances51. However, in many degraded reef areas current management is insufficient to control ongoing threats, and the loss of coral populations is so severe that larval supply is limited by the reduction in breeding corals and elevated rates of post-settlement juvenile coral mortality resulting from poor water quality and other chronic disturbances. Therefore, new active management approaches are needed for effectively slowing and reversing coral loss on degraded reef systems to promote recovery.

The loss of live coral cover and fish abundance on reefs in the Bolinao-Anda Reef Complex (BARC) in Northern Luzon since the early 1980s27 typifies the declining reef status in many regions in the Philippines and more broadly in southeast Asia over recent decades2,7. The BARC reefs were originally characterised by high live coral cover, fish abundance and high biodiversity27, however the experimental reef plots at Magsaysay reef and most nearby reef areas now have ‘very poor live coral cover’ sensu Wilkinson2. Furthermore, these reefs are now dominated by macroalgae, turf algae and dead coral (Fig. 2), consistent with a phase shift from coral to algal dominance52. Despite their poor status, environmental conditions at Magsaysay reef (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table S1) and other reefs nearby are sufficient for at least some adult corals to survive (Fig. 2) and the key threat of blast fishing has now been controlled53. However, the low rates of recruitment at the reef site during this study indicates that natural recovery of coral populations on these reefs will be slow and may not occur without active intervention54.

The results of this study demonstrate for the first time that mass larval supply resulting in enhanced rates of settlement directly onto badly degraded reef areas can significantly increase coral recruitment. As expected the highest rate of juvenile mortality occurred during the first few months after settlement, resulting in a Type III survivorship curve typical of many broadcast spawning marine invertebrates55 including corals56–62. The sources of early juvenile mortality could not be determined but are likely to include competition, overgrowth and potential allelopathic effects of algae57,59, competition with other reef invertebrates63,64, herbivore grazing and carnivore predation65–67, sedimentation and eutrophication68,69 and stochastic disturbances50. In addition, some coral recruits may have died after the first settlement census due to insufficient energy reserves remaining after settlement and initial skeletogenesis58, prior to the uptake and establishment of mutualistic Symbiodinium communities and the supply of photosynthetic energy-rich compounds70.

In contrast to some other field studies that were terminated due to low or no recruit survival, longer-term repeated monitoring during the present study showed remarkably high survivorship and growth of recruits occurred after five to nine months until 35 months (Fig. 4). This pattern of increased survival likely reflects the importance of early rapid growth to reach size-escape thresholds that result in increased survival and recruitment success59,61,71,72. High survival of recruits occurred after nine months with only five colonies that settled on tiles dying between 24 and 32 months post-settlement. Of these, only one of the A. tenuis colonies derived from the larval enhancement experiment bleached and died during the coral bleaching event at 26 months after settlement. Similar low rates of bleaching were observed among other Acropora colonies near the experimental site, with highest levels of bleaching in pocilloporid and fungiid corals. Predation by muricid Drupella corallivores resulted in the death of four of the larger colonies growing on tiles during December 2015, but no colonies growing on reef substrata were preyed upon. Predation by Drupella was also recorded to have reduced survival of some transplanted A. millepora juveniles on another BARC reef in a previous study67.

Mean growth rates of A. tenuis colonies resulting from settlement of reared larvae were similar on the natural reef substrata and coral skeleton tiles (Fig. 7) and these corals grew faster (5.2 cm yr−1) compared to cultured A. tenuis that were settled on artificial substrata in an outdoor hatchery, and subsequently transplanted after 18 months to reef habitats in subtropical Akajima Island, Okinawa, Japan (4 cm yr−1)73. Corals from the present study also grew faster than hatchery cultured A. millepora colonies where sub-adults were transplanted onto BARC reef outcrops (4.6 cm yr−1 mean diameter) or maintained in in situ nurseries for 3 years (4 cm yr−1 mean diameter)67,74. The relatively rapid growth rates of corals in the present study indicate the environmental conditions at Magsaysay reef are suitable for at least some corals, and that the surviving colonies are adapted to these conditions. Rapid growth may also have been enhanced by larvae selecting suitable natural microhabitat refuges and microbial communities directly on the reef, whereas larvae settled in ex situ or in situ nurseries will experience different physico-chemical and microbial conditions compared with those experienced by juvenile or sub-adult corals subsequently transplanted to different reef sites67,73,74. This may cause some transplanted colonies to be maladapted to their new environments and is an important issue that needs to be considered in future coral restoration projects involving transplantation of corals after settlement75.

The fastest growth and largest volume was recorded for the colony that resulted from the fusion of 31 individual juvenile corals on the reef between 15 and 17 months of age. This fused colony subsequently exhibited irregular growth morphology (Fig. 6) and patches of different coloured polyp tissues indicating that it is a chimera resulting from multiple genotypes. Intracolonial genetic variability and chimerism has been reported in some wild adult reef coral populations including other Acropora species76,77 and could be used to enhance coral restoration efforts. Fusion of different genotypes increases juvenile colony size and growth to larger size refuges thereby increasing survival potential unless competition among genotypes or tissue resorption and cell parasitism results in detrimental impacts61.

Rapid colony growth resulted in the establishment of a new breeding population of A. tenuis on the degraded reef site within three years after larval settlement (Fig. 6), and these colonies will increase the supply of gametes and larvae available for potential recruitment on other reefs in the Lingayen Gulf in the future. These recruits became sexually reproductive and spawned earlier and at smaller mean colony sizes than cultured and transplanted juveniles of A. tenuis from Akajima Island, where some surviving colonies became sexually reproductive at age 4–5 years when they had grown to 20–25 cm mean diameter73. The results from the present study support the earlier estimate of a minimum age at first reproduction of 3–5 years for Acropora recruits78, and are similar to the age and colony sizes at first reproduction for A. millepora recruits that were reared ex situ and transplanted onto BARC reef areas74.

Although low numbers of Acropora spat were recorded on recruitment tiles at the study site, no new visible A. tenuis natural recruits appeared in any plot during the three year study. This indicates that if any natural A. tenuis larvae were present and did settle on the reef substrata, none survived to visible size. These results indicate that natural background acroporid larval supply and recruitment are currently very limited at these degraded reef plots, hence these reef areas will have very slow rates of Acropora population recovery without active intervention. The lack of recovery at Magsaysay reef is also likely to be influenced by the availability of suitable substrata, potential exclusion or competition from other benthic organisms, and high post-settlement mortality of settled spat. Similar issues of natural recruitment limitation and failure have been documented on Caribbean reefs79 where coral cover and spawning biomass have been decreasing for some decades13. In these situations, reef recovery requires active intervention to increase the supply of genetically diverse larvae to ensure successful recruitment and survival at rates higher than the mortality of adult populations.

Transplantation of coral fragments on degraded BARC reefs has been shown to significantly increase the abundance and diversity of reef fish and macroinvertebrates54,80. Therefore, the re-establishment of complex three-dimensional habitats from the growth of reef-building corals from this study (Fig. 6) is likely to increase biodiversity and biomass of reef organisms on the restoration site, leading to improved reef status and ecosystem services81.

It has been noted that for future reef restoration interventions to have impacts at meaningful scales, they must be effective, relatively simple and affordable16. This study used organza cloth for the larval enclosures as this material is commonly available and relatively inexpensive, allows water to flow through the mesh to maintain larvae in a healthy condition and is sturdy enough to withstand intermittent strong surges on the reef site. The use of these low-cost enclosures helped to reduce the total production cost for this study to US$1654.00, and an average production cost of $20.94 for each of the colonies surviving after 35 months. The ~$21 cost for each three year old A. tenuis colony derived from larvae settled directly onto the reef plots and coral tiles is substantially less expensive than the production costs of 2.5 year A. millepora coral transplants that were held in an in situ nursery for 7 months (US$284), 14 months ($217) or 19 months ($61) prior to transplantation to reef sites67. Production costs for 2.5 year old A. palmata recruits ranged from US$325 for corals reared in a land-based nursery, to $13 for corals outplanted onto a reef after two weeks82.

Although post-settlement mortality is a key challenge and potential bottleneck for coral recruitment, our results clearly demonstrate that larval settlement and recruitment of Acropora coral species can be significantly enhanced using mass larval settlement to rapidly initiate coral population restoration and fast growth to sexual maturity within three years, even on degraded reef areas. Early post-settlement mortality can be ameliorated through the use of increased concentrations of competent coral larvae to substantially increase initial settlement rates and recruitment overall. This combined with high survival of juvenile corals indicates that mass larval enhancement is a viable and relatively low-cost active restoration option for initiating coral population recovery on degraded reefs, where environmental conditions are suitable for reef corals to grow but natural recruitment is limited, and chronic disturbances and key threats are effectively managed.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff and research assistants and many volunteer helpers at the Bolinao Marine Laboratory of the Marine Science Institute, University of the Philippines for logistical support with this research. We thank M. van Oppen and S. Whalan for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. This publication is dedicated to our colleague at BML, Dr Ronald D. Villanueva who became terminally ill during 2015. This study was funded by Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) grants SRA FIS/2011/031 and FIS/2014/063 to P.L.H. We thank C. Barlow from ACIAR for ongoing support. This is an MSI Contribution.

Author Contributions

D.W.d.C. and P.L.H. conceived and designed the experiment. P.L.H. secured all the funding for the research and D.W.d.C. collected the data. D.W.d.C. and P.L.H. interpreted the data and P.L.H. and D.W.d.C. wrote the paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-14546-y.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hoegh-Guldberg O, et al. Coral reefs under rapidclimate change and ocean acidification. Science. 2007;318:1737–1742. doi: 10.1126/science.1152509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilkinson, C. Status of Coral Reefs of the World: 2008. (Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network and Reef and Rainforest Research Centre, 2008).

- 3.Pandolfi JM, Connolly SR, Marshall DJ, Cohen AL. Projecting coral reef futures under global warming and ocean acidification. Science. 2011;333:418–422. doi: 10.1126/science.1204794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruno JF, Selig ER. Regional decline of coral cover in the Indo-Pacific: timing, extent, and subregional comparisons. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e711. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carpenter KE, et al. One-third of reef-building corals face elevated extinction risk from climate change and local impacts. Science. 2008;321:560–563. doi: 10.1126/science.1159196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De’ath G, Fabricius KE, Sweatman H, Puotinen M. The 27–year decline of coral cover on the Great Barrier Reef and its causes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:17995–17999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208909109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke, L., Reytar, K., Spalding, M. & Perry, A. Reefs at Risk Revisited. (World Resources Institute, 2011).

- 8.Roberts CM, et al. Marine biodiversity hotspots and conservation priorities for tropical reefs. Science. 2002;295:1280–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.1067728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Groot RS, et al. Global estimates of the value of ecosystems and their services in monetary units. Ecosyst. Serv. 2012;1:50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2012.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richmond, R. H. Reproduction and recruitment in corals: critical links in the persistence of reefs. Life and Death of Coral Reefs. (ed. Birkeland, C.E.) 175–197 (Chapman & Hall, 1997).

- 11.Harrison, P. L. Sexual reproduction of scleractinian corals. Coral Reefs: an Ecosystem in Transition. (eds Dubinsky, Z., Stambler, N.) 59–85 (Springer, 2011).

- 12.Oliver J, Babcock R. Aspects of the fertilization ecology of broadcast spawning corals: sperm dilution effects and in situ measurements of fertilization. Biol. Bull. 1992;183:409–417. doi: 10.2307/1542017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes TP, Tanner JE. Recruitment failure, life histories, and long-term decline of Caribbean corals. Ecology. 2000;81:2250–2263. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081[2250:RFLHAL]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albright R, Mason B, Miller M, Langdon C. Ocean acidification compromises recruitment success of the threatened Caribbean coral Acropora palmata. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:20400–20404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007273107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rinkevich B. Conservation of coral reefs through active restoration measures: recent approaches and last decade progress. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39:4333–4342. doi: 10.1021/es0482583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards, A. J. Reef restoration manual. 166 (Coral Reef Targeted Research & Capacity Building for Management Program, 2010).

- 17.Young C, Schopmeyer S, Lirman D. A review of reef restoration and coral propagation using the threatened genus Acropora in the Caribbean and Western Atlantic. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2012;88:1075–1098. doi: 10.5343/bms.2011.1143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barton, J. A., Willis, B. L. & Hutson, K. S. Coral propagation: a review of techniques for ornamental trade and reef restoration. Rev. Aquacult. 1–19 (2015).

- 19.Shearer T, Porto I, Zubillaga A. Restoration of coral populations in light of genetic diversity estimates. Coral Reefs. 2009;28:727–733. doi: 10.1007/s00338-009-0520-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Babcock R, et al. Synchronous spawnings of 105 scleractinian coral species on the Great Barrier Reef. Mar. Biol. 1986;90:379–394. doi: 10.1007/BF00428562. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrison, P. & Wallace, C. Reproduction, dispersal and recruitment of scleractinian corals. Ecosystems of the World 25: Coral Reefs (ed. Dubinsky, Z.) 133–207 (Elsevier, 1990).

- 22.Charmantier A, Garant D. Environmental quality and evolutionary potential: lessons from wild populations. Proc. Roy. Soc. B. 2005;272:1415–1425. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Oppen MJ, Oliver JK, Putnam HM, Gates RD. Building coral reef resilience through assisted evolution. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2015;112:2307–2313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1422301112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heyward A, Smith L, Rees M, Field S. Enhancement of coral recruitment by in situ mass culture of coral larvae. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2002;230:113–118. doi: 10.3354/meps230113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edwards AJ, et al. Direct seeding of mass-cultured coral larvae is not an effective option for reef rehabilitation. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2015;525:105–116. doi: 10.3354/meps11171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gomez E, Alcala AC, San Diego AC. Status of Philippine coral reefs - 1981. Proc. 4th Int. Coral Reef Symp. 1981;1:275–282. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cruz-Trinidad A, Geronimo RC, Aliño PM. Development trajectories and impacts on coral reef use in Lingayen Gulf, Philippines. Ocean Coast. Manage. 2009;52:173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2008.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomez E, Alino P, Yap H, Licuanan W. A review of the status of Philippine reefs. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1994;29:62–68. doi: 10.1016/0025-326X(94)90427-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohler KE, Gill SM. Coral Point Count with Excel extensions (CPCe): A Visual Basic program for the determination of coral and substrate coverage using random point count methodology. Comp. Geosci. 2006;32:1259–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.cageo.2005.11.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mundy C. An appraisal of methods used in coral recruitment studies. Coral Reefs. 2000;19:124–131. doi: 10.1007/s003380000081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lane A, Harrison P. Effects of contaminants on survivorship of larvae of the scleractinian reef corals Acropora tenuis, Goniastrea aspera, Platygyra sinensis from the Great Barrier Reef. Proc. 9th Int. Coral Reef Symp. 2002;1:403–408. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baria MVB, et al. Caging enhances post-settlement survival of juveniles of the scleractinian coral Acropora tenuis. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2010;394:149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2010.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Omori M. Degradation and restoration of coral reefs: Experience in Okinawa, Japan. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2011;7:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wallace, C. C. Staghorn Corals of the World: A revision of the coral genus Acropora (Scleractinia; Astroncoeniina; Acroporidae) worldwide, with emphasis on morphology, phylogeny and biogeography. (CSIRO, 1999).

- 35.Harrison PL, et al. Mass spawning in tropical reef corals. Science. 1984;223:1186–1189. doi: 10.1126/science.223.4641.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Willis B, et al. Patterns in the mass spawning of corals on the Great Barrier Reef from 1981 to 1984. Proc. Fifth Int. Coral Reef Congr. 1985;4:343–348. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vicentuan K, et al. Multi-species spawning of corals in north-western Philippines. Coral Reefs. 2008;27:83. doi: 10.1007/s00338-007-0325-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson J, Harrison P. Settlement-competency periods of larvae of three species of scleractinian corals. Mar. Biol. 1998;131:339–345. doi: 10.1007/s002270050327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heyward A, Negri A. Natural inducers for coral larval metamorphosis. Coral Reefs. 1999;18:273–279. doi: 10.1007/s003380050193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harrison, P. Settlement competency periods and dispersal potential of scleractinian reef coral larvae. Proc 10thInt. Coral Reef Symp. 78–82 (2006).

- 41.Willis B, Babcock R, Harrison P, Wallace C. Experimental hybridization and breeding incompatibilities within the mating systems of mass spawning reef corals. Coral Reefs. 1997;16:S53–S65. doi: 10.1007/s003380050242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishikawa A, Katoh M, Sakai K. Larval settlement rates and gene flow of broadcast-spawning (Acropora tenuis) and planula-brooding (Stylophora pistillata) corals. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2003;256:87–97. doi: 10.3354/meps256087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keough MJ, Downes BJ. Recruitment of marine invertebrates: the role of active larval choices and early mortality. Oecologia. 1982;54:348–352. doi: 10.1007/BF00380003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ritson-Williams, R. et al. New perspectives on ecological mechanisms affecting coral recruitment on reefs. Smithsonian Contrib. to the Mar. Sci. 437 (2009).

- 45.Shaish L, Levy G, Gomez E, Rinkevich B. Fixed and suspended coral nurseries in the Philippines: Establishing the first step in the “gardening concept” of reef restoration. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2008;358:86–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2008.01.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Babcock RC, et al. Identification of scleractinian coral recruits from Indo-Pacific reefs. Zool. Stud. 2003;42:211–226. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gardner, W. D. Field assessment of sediment traps. J. Mar. Res. 38 (1980).

- 48.Doty MS. Measurement of water movement in reference to benthic algal growth. Bot. Mar. 1971;14:32–35. doi: 10.1515/botm.1971.14.1.32. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee, E. T. & Wang, J. Statistical Methods for Survival Data Analysis. 3rd edn (John Wiley & Sons, 2003).

- 50.Connell JH, Hughes TP, Wallace CC. A 30-year study of coral abundance, recruitment, and disturbance at several scales in space and time. Ecol. Monogr. 1997;67:461–488. doi: 10.1890/0012-9615(1997)067[0461:AYSOCA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gilmour JP, et al. Recovery of an isolated coral reef system following severe disturbance. Science. 2013;340:69–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1232310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bruno JF, et al. Assessing evidence of phase shifts from coral to macroalgal dominance on coral reefs. Ecology. 2009;90:1478–1484. doi: 10.1890/08-1781.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.dela Cruz DW, Rinkevich B, Gomez ED, Yap HT. Assessing an abridged nursery phase for slow growing corals used in coral restoration. Ecol. Eng. 2015;84:408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2015.09.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.dela Cruz DW, Villanueva RD, Baria MVB. Community-based, low-tech method of restoring a lost thicket of Acropora corals. ICES J Mar. Sci. 2014;71:1866–1875. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fst228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roughgarden J, Iwasa Y, Baxter C. Demographic theory for an open marine population with space-limited recruitment. Ecology. 1985;66:54–67. doi: 10.2307/1941306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Babcock R. Growth and mortality in juvenile corals (Goniastrea, Platygyra and Acropora): the first year. Proc. 5th Int. Coral Reef Symp. 1985;2:355–360. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harrington L, Fabricius K, De’Ath G, Negri A. Recognition and selection of settlement substrata determine post-settlement survival in corals. Ecology. 2004;85:3428–3437. doi: 10.1890/04-0298. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilson J, Harrison P. Post-settlement mortality and growth of newly settled reef corals in a subtropical environment. Coral Reefs. 2005;24:418–421. doi: 10.1007/s00338-005-0033-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vermeij MJ, Sandin SA. Density-dependent settlement and mortality structure the earliest life phases of a coral population. Ecology. 2008;89:1994–2004. doi: 10.1890/07-1296.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Doropoulos C, et al. Characterizing the ecological trade-offs throughout the early ontogeny of coral recruitment. Ecol. Monogr. 2016;86:20–44. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Raymundo LJ, Maypa AP. Getting bigger faster: mediation of size-specific mortality via fusion in junenile coral transplants. Ecol. Appl. 2004;14:281–295. doi: 10.1890/02-5373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cooper WT, et al. Assessing techniques to enhance early post-settlement survival of corals in situ for reef restoration. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2014;90:651–664. doi: 10.5343/bms.2013.1020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Birkeland, C. The importance of rate of biomass accumulation in early successional stages of benthic communities to the survival of coral recruits Proc. 3rdInt. Coral Reef Symp. 15–21 (1977).

- 64.Sammarco PW. Echinoid grazing as a structuring force in coral communities: whole reef manipulations. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1982;61:31–55. doi: 10.1016/0022-0981(82)90020-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brock R. An experimental study on the effects of grazing by parrotfishes and role of refuges in benthic community structure. Mar. Biol. 1979;51:381–388. doi: 10.1007/BF00389216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sammarco PP, Carleton JJ. Damselfish territoriality and coral community structure: reduced grazing, coral recruitment, and effects on coral spat. Proc. 4th Int. Coral Reef Symp. 1981;2:525–535. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guest J, et al. Closing the circle: is it feasible to rehabilitate reefs with sexually propagated corals? Coral Reefs. 2014;33:45–55. doi: 10.1007/s00338-013-1114-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ward S, Harrison P. The effects of elevated nutrients on settlement of coral larvae during the ENCORE experiment. Proc. 8th Int. Coral Reef Symp. 1997;1:891–896. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Humanes A, et al. Cumulative effects of suspended sediments, organic nutrients and temperature stress on early life history stages of the coral Acropora tenuis. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:44101. doi: 10.1038/srep44101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Quigley KM, Willis BL, Bay LK. Maternal effects and Symbiodinium community composition drive differential patterns in juvenile survival in the coral Acropora tenuis. Royal Society Open Science. 2016;3:160471. doi: 10.1098/rsos.160471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Doropoulos C, et al. Interactions among chronic and acute impacts on coral recruits: the importance of size-escape thresholds. Ecology. 2012;93:2131–2138. doi: 10.1890/12-0495.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Babcock RC. Comparative demography of three species of scleractinian corals using age‐and size-dependent classifications. Ecol. Monogr. 1991;61:225–244. doi: 10.2307/2937107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Iwao K, Omori M, Taniguchi H, Tamura M. Transplanted Acropora tenuis (Dana) spawned first in their life 4 years after culture from eggs. Galaxea. 2010;12:47–47. doi: 10.3755/galaxea.12.47. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Baria MVB, dela Cruz DW, Villanueva RD, Guest JR. Spawning of three-year-old Acropora millepora corals reared from larvae in northwestern Philippines. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2012;88:61–62. doi: 10.5343/bms.2011.1075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Baums IB. A restoration genetics guide for coral reef conservation. Mol. Ecol. 2008;17:2796–2811. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Puill-Stephan E, Willis BL, van Herwerden L, van Oppen MJ. Chimerism in wild adult populations of the broadcast spawning coral Acropora millepora on the Great Barrier Reef. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7751. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schweinsberg M, et al. More than one genotype: how common is intracolonial genetic variability in scleractinian corals? Mol. Ecol. 2015;24:2673–2685. doi: 10.1111/mec.13200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wallace CC. Reproduction, recruitment and fragmentation in nine sympatric species of the coral genus. Acropora. Mar. Biol. 1985;88:217–233. doi: 10.1007/BF00392585. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.van Woesik R, Scott WJ, Aronson RB. Lost opportunities: coral recruitment does not translate to reef recovery in the Florida Keys. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014;88:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cabaitan PC, Gomez ED, Aliño PM. Effects of coral transplantation and giant clam restocking on the structure of fish communities on degraded patch reefs. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2008;357:85–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2008.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.de Groot RS, et al. Benefits of investing in ecosystem restoration. Conserv. Biol. 2013;27:1286–1293. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chamberland VF, et al. Restoration of critically endangered elkhorn coral (Acropora palmata) populations using larvae reared from wild-caught gametes. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2015;4:526–537. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2015.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.