Abstract

Background

Static encephalopathy of childhood with neurodegeneration in adulthood is a phenotypically distinctive, X-linked dominant subtype of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA). WDR45 mutations were recently identified as causal. WDR45 encodes a beta-propeller scaffold protein with a putative role in autophagy, and the disease has been renamed beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration (BPAN).

Case Report

Here we describe a female patient suffering from a classical BPAN phenotype due to a novel heterozygous deletion of WDR45. An initial gene panel and Sanger sequencing approach failed to uncover the molecular defect. Based on the typical clinical and neuroimaging phenotype, quantitative polymerase chain reaction of the WDR45 coding regions was undertaken, and this showed a reduction of the gene dosage by 50% compared with controls.

Discussion

An extended search for deletions should be performed in apparently WDR45-negative cases presenting with features of NBIA and should also be considered in young patients with predominant intellectual disabilities and hypertonia/parkinsonism/dystonia.

Keywords: Static encephalopathy of childhood with neurodegeneration in adulthood, SENDA, BPAN, beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration, NBIA, WDR45

Introduction

Static encephalopathy of childhood with neurodegeneration in adulthood (SENDA) is a phenotypically distinctive, X-linked dominant subtype of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA). WDR45 mutations were recently identified as causal.1,2 WDR45 encodes a beta-propeller scaffold protein with a putative role in autophagy. Therefore the disease was renamed beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration (BPAN).1,2

Case report

Here we describe a 30-year-old female patient born at term as the first child to healthy unrelated parents from Germany. Her early postnatal adaption was reportedly normal, but her psychomotor development was delayed and she was able to sit unaided at the age of 12 months and walk with assistance at the age of 2 years. She spoke her first words at the age of 2 and her expressive language remained limited to single words. She suffered from febrile convulsions from the age of 2.5 years, followed by the diagnosis and treatment of epilepsy by the age of 3 years. At that time she lost her language abilities and became incontinent. Her condition subsequently remained stable until the age of 24 years. She attended a school for children with special needs and was able to walk with assistance, although her gait was hypertonic and dystonic. By the age of 24 years, she developed additional symptoms including yelling, progressive gait disturbance, and swallowing deficits with the need of tube feeding by the age of 28 years. From the age of 29 she was completely wheelchair dependent. Wilson’s disease and Rett syndrome had been excluded by neuroimaging, laboratory examinations or genetic testing. There were no signs of retinitis pigmentosa. Neuroimaging (Figure 1) revealed hypointensities within the basal ganglia suggestive of NBIA3,4 and the typical T1 hyperintense signals in the midbrain. Sequencing of PKAN was negative.

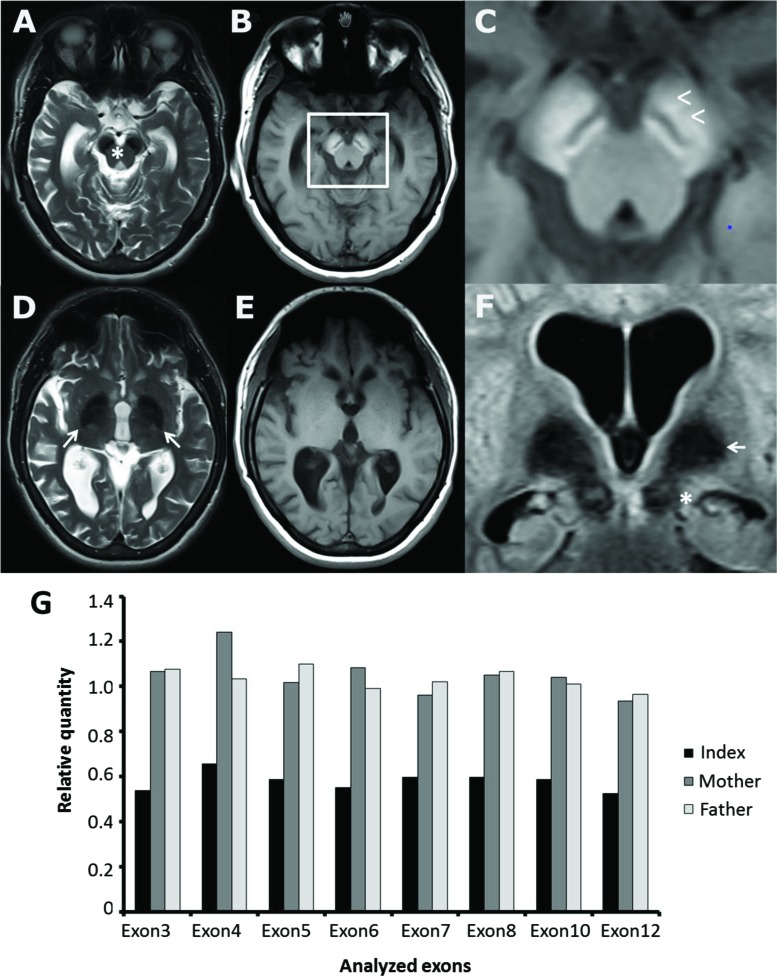

Figure 1. Neuroimaging and Genetics of Referred Patient. (A–F) Patient brain magnetic resonance imaging panel displaying T2 weighted (A,D) and T1 weighted scans of consecutive axial slices at mesencephalic and basal ganglia level. Beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration (BPAN) typical signal changes were found as symmetric cerebral peduncle including substantia nigra T2 hypointensity (A,F;*) combined with T1 hyperintensity (B) with a located circumscribed hypointense band in there (B and enlarged section C;<) as described to be a nearly pathognomonic magnetic resonance imaging feature of BPAN. In contrast, symmetric T2 hypointensity of the globus pallidus (D,F;→) was not accompanied by T1 signal changes (E). Global cerebral atrophy and caudate nucleus atrophy were observed. (G) Quantitative polymerase chain reaction of the WDR45 coding regions of the index patient and her parents showing a reduction of the gene dosage to approximately 50% of controls suggestive of a heterozygous deletion of the entire WDR45 gene.

At the age of 30 years she was unable to communicate or follow commands. She only had an intermittent fixation, showed a vertical gaze palsy, generalized severe hypertonia with signs of both spasticity and dystonia, hyperlordosis, bilateral hand dystonia and club feet, striatal toe, and increased tendon reflexes. Levodopa treatment did not yield significant amelioration while intrathecal baclofen pump therapy was helpful to reduce muscle tone. Oral medications were as follows (daily dose): omeprazole 20 mg, metoclopramide 30 mg, prucalopride 1 mg, macrogol 26 g, propiverine 45 mg, lamotrigine 450 mg, doxepin 40 mg. In addition, she had transdermal fentanyl transdermal system (12 µg) and continuous intrathecal baclofen pump therapy with a daily dose of 70 µg.

Panel diagnostics and Sanger sequencing did not reveal any potentially pathogenic sequence variants in WDR45 (data not shown).2,5 We then broadened the genetic diagnostics to include genes associated with other atypical forms of NBIA (including PLA2G6, C9ORF12, FTL, FA2H, ATP13A2, CP),3 and Nieman–Pick’s disease due to the vertical gaze palsy (NPC1, NPC2). All of them gave negative results.

Owing to the distinct classical clinical presentation and neuroimaging findings (Figure 1), we further analyzed the WDR45 gene by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). By doing so, we detected a heterozygous deletion of the entire WDR45 gene (Figure 1B). Testing of parental blood-derived DNA suggested that the variant occurred de novo. The karyotype was normal. Array-Comparative genomic hybriditation (CGH) showed a normal karyotype without signs for microdeletions or microduplications.

Methylation of one copy of the X chromosome in each female cell may result in one cell population expressing the wild-type allele and the other expressing the mutant allele. Skewing of X-inactivation has been discussed as a modifying disease mechanism in BPAN, providing a possible explanation for the strikingly uniform clinical presentation of males and females.5,6 Keeping in mind that methylation patterns observed in blood cells do not necessarily reflect those in the affected tissue, skewed X-inactivation has been observed in 13 out of 15 patients analyzed, likely resulting in the expression of the mutant allele.5 In our patient, X-inactivation studies using the HUMARA assay indicated an extremely skewed methylation pattern (95:5) in genomic DNA derived from peripheral blood cells.

Discussion

We report on a female with a characteristic BPAN phenotype caused by a heterozygous deletion of the entire WDR45 gene. This finding was initially missed in routine genetic testing, but it was subsequently identified in an extended screening strategy including qPCR. This analysis was initiated based on the distinct clinical features and course of the disease. The case also highlights the interesting phenotype of a disease showing a biphasic disease course with a remarkable long “static” phase, which was eponymous for the initial term static encephalopathy of childhood with neurodegeneration in adulthood. However, the term encephalopathy may be open to debate in a neurodegenerative disease. Copy number variants (CNVs) affecting WDR45 might therefore represent an underdiagnosed cause of neurodegenerative disorders. We suggest that an extended search for deletions should be performed in apparently WDR45-negative cases presenting with features of NBIA and should also be considered in young patients with predominant intellectual disabilities and hypertonia/parkinsonism/dystonia.

Methods

Sanger sequencing

The coding region and the flanking exon–intron boundaries of the genes ATP13A2, C19ORF12, CP, FA2H, FTL, NPC1, NPC2, PLA2G6, and WDR45 were amplified by PCR and the amplification products were sequenced by direct bidirectional Sanger sequencing according to standard protocols using the 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

MLPA

Deletion and duplication analysis of the genes PLA2G6, NPC1, and NPC2 was performed using multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA, MRC Holland), and the SALSA MLPA kits P120-B1 (PLA2G6) and P193-A2 (NPC1, NPC2) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Deletions and duplications affecting the WDR45 gene (NM_007075.3) were analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR using the KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR Master Mix (Kapa Biosystems) and the QuantStudio 12K Flex system (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol with intragenic amplicons in the coding exons 3–8, 10, and 12 and in three reference amplicons.

Array CGH

CytoChip Oligo arrays were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BlueGenome/Agilent, GB).

Humara assay

We used genomic DNA derived from whole blood cells to investigate X-inactivation patterns in the patient as described previously.6

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Sandra Jackson for help with editing.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Financial Disclosures: None.

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Ethics Statement: This study was reviewed by the authors’ institutional ethics committee and was considered exempted from further review.

References

- 1.Hayflick SJ, Kruer MC, Gregory A, Haack TB, Kurian MA, Houlden HH, et al. Beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration: a new X-linked dominant disorder with brain iron accumulation. Brain. 2013;(Pt 6):1708–1717. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt095. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saitsu H, Nishimura T, Muramatsu K, Kodera H, Kumada S, Sugai K, et al. De novo mutations in the autophagy gene WDR45 cause static encephalopathy of childhood with neurodegeneration in adulthood. Nat Genet. 2013;45:445–449. doi: 10.1038/ng.2562. 9e1. doi: 10.1038/ng.2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gregory A, Hayflick S. Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation disorders overview. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, Bean LJH, et al., editors. GeneReviews(R) Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tschentscher A, Dekomien G, Ross S, Cremer K, Kukuk GM, Epplen JT, et al. Analysis of the C19orf12 and WDR45 genes in patients with neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation. J Neurol Sci. 2015;349:105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.12.036. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haack TB, Hogarth P, Kruer MC, Gregory A, Wieland T, Schwarzmayr T, et al. Exome sequencing reveals de novo WDR45 mutations causing a phenotypically distinct, X-linked dominant form of NBIA. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:1144–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.10.019. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen RC, Zoghbi HY, Moseley AB, Rosenblatt HM, Belmont JW. Methylation of HpaII and HhaI sites near the polymorphic CAG repeat in the human androgen-receptor gene correlates with X chromosome inactivation. Am J Hum Genet. 1992;51:1229–1239. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]