Abstract

Aim: To examine the association between the serum endostatin levels and subclinical atherosclerosis independent of traditional risk factors in a healthy Japanese population.

Methods: Among 1,057 residents who attended free public physical examinations between 2010 and 2011, we evaluated the data of 648 healthy residents for whom the serum endostatin level and common carotid intima-media thickness (IMT) were successfully measured.

Results: The median endostatin level was 63.7 ng/mL (interquartile ranges: 49.7–93.2 ng/mL), and the mean carotid IMT was 0.68 ± 0.12 mm. Residents with above median endostatin had significantly higher carotid IMT than did those with below median endostatin (0.71 ± 0.14 vs. 0.65 ± 0.09 mm, P < 0.001). Multiple linear regression analysis demonstrated that increased serum endostatin is significantly associated with carotid IMT (above vs. below median endostatin level; beta = 0.11, P = 0.03), independent of the known covariates of age, sex, body mass index, drinking and smoking status, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, hemoglobin A1c, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and log-transformed high sensitive C-reactive protein.

Conclusions: A higher serum endostatin level reflected subclinical atherosclerosis in this Japanese population.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, Carotid intima-media thickness, Endostatin, Epidemiology

See editorial vol. 24: 1014–1015

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a pathologic process that causes intima medial thickening, plaque formation, and sometimes occlusion of the coronary, cerebral, and peripheral arteries1). Endostatin is a cleavage of the C-terminal domain of collagen XVIII, a component of the extracellular matrix1), and a potent endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor in vivo and in vitro2, 3). Recent observational studies have shown that circulating endostatin is associated with cerebrovascular diseases4), the severity of kidney dysfunction5), hypertensive organ damage6), and future cardiovascular mortality7). Thus, the circulating level of endostatin is thought to reflect extracellular matrix remodeling and be a useful marker for subclinical cardiovascular damage. However, these reports were limited to elderly participants or patients with cardiovascular or chronic kidney disease (CKD); thus, further research in a relatively healthy population is necessary.

Carotid arterial intima-media thickness (IMT), a marker of subclinical atherosclerosis8), is a predictor of future cardiovascular events9) and the incidence of CKD10). It is also reported that matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which generate endostatin from the extracellular matrix, are associated with carotid IMT11, 12). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that the serum endostatin levels would be positively associated with carotid IMT. To examine this hypothesis, we analyzed this relationship in a healthy Japanese population.

Subjects and Methods

Study Participants

This study is part of the Kyushu and Okinawa Population Study (KOPS) survey of vascular events associated with lifestyle-related diseases10, 13–15). Eligible participants were 1,057 residents who took part in free public physical examinations between 2010 and 201113). The following residents were excluded from analysis: 1) 28 because of insufficient data; 2) 44 who did not agree to undergo carotid ultrasonographic measurement; 3) 77 who had a history of cardiovascular disease, malignancy, or a chronic inflammatory disease (collagen disease or inflammatory bowel disease); 4) 260 receiving treatment for hypertension, diabetes, or dyslipidemia. After exclusions, the data of 648 subjects (200 men and 448 women) were available for analysis. The age of the subjects ranged from 24 to 84 years [mean ± standard deviation (SD): 56.3 ± 10.6 years]. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to the examination. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Some of the data from the KOPS were published previously10, 13–15).

Anthropometric Measurement and Questionnaire

Anthropometric measurements were performed with each subject wearing indoor clothing and without shoes. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight [kg] divided by height [m] squared. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP) were measured on the right arm, in the sitting position, with an automated sphygmomanometer (HEM-780, Omron Healthcare, Kyoto, Japan) after a five minute rest.

Each subject completed a self-administrated questionnaire to gather information about personal medical history, family medical history, use of drugs, smoking status (current or non-current), and alcohol consumption (habitual or non-habitual). The questionnaire was checked for unfilled or inconsistent answers, first by nurses and again by our staff physicians.

Laboratory Measurements

As part of a free public physical examination, blood samples were collected after an 8 hour overnight fast to determine the serum levels of creatinine, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), and low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. Aliquots of whole blood and fresh plasma and serum samples after separation were stored at 4°C in refrigerated containers and sent to a commercial laboratory (SRL Inc, Tokyo, Japan). The HbA1c level was measured from a fresh whole blood sample using the immune coherent method (RAPIDIA Auto HbA1c, Fujirebio Diagnostics Inc., Tokyo, Japan), with results expressed as the US National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program format level (%). The serum level of LDL cholesterol was determined by automated standardized enzymatic analysis (Determiner L LDL-C, Kyowa Medex Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). The serum creatinine level was measured by enzymatic assay. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the modification of diet in renal disease study equation modified for Japanese subjects: eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) = 194 × age−0.287 × serum creatinine (mg/dL)−1.094 (if woman × 0.739)16). High sensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) was measured by means of particle-enhanced immunonephelometry (N-latex CRP II, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics K.K., Tokyo, Japan).

All remaining fasting serum samples were immediately frozen and stored at −80°C until assayed. The serum endostatin level (range: 16–500 ng/mL) was measured from defrosted samples using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, USA). Assessment of reproducibility testing showed good results, the recovery rate for spiked samples was 91%–108%, and there was no influence of interfering substances at normal levels. The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 5.0% and 6.4%, respectively.

Ultrasonographic Measurement

Carotid IMT was assessed by ultrasound. The subjects were supine with a slight hyperextension and rotation of the neck in the direction opposite the probe. Carotid artery lesions were measured using high resolution B-mode ultrasonography with a 7.5 MHz linear array probe (UF-4300R®, Fukuda Denshi Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) by the well trained physicians of our department. Images were obtained 20 mm proximal to the origin of the carotid bulb at the far wall by the IMT measurement software, Intimascope (Media Cross Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan)17). The mean value of the bilateral average mean-IMT level was used as mean carotid IMT level.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the means ± SD or percentage. Because the distributions of the serum endostatin and hs-CRP levels were highly skewed, they were log-transformed before the statistical analysis and expressed as the median (interquartile ranges). The univariate associations between carotid IMT and clinical variables were assessed using Pearson's correlation coefficient analysis (categorical variables were compared with the difference between groups). For comparisons of participants with an above/below median serum endostatin level, unpaired Student's t-test was used to compare mean values, and the chi-square test was used to evaluate differences in prevalence rates. Analysis of covariance was performed to detect differences between participants with an above/below median serum endostatin level after adjustment for confounding factors. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS ver.22.0 (SPSS Inc., IBM, Somers, NY). A two-tailed P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical Characteristics

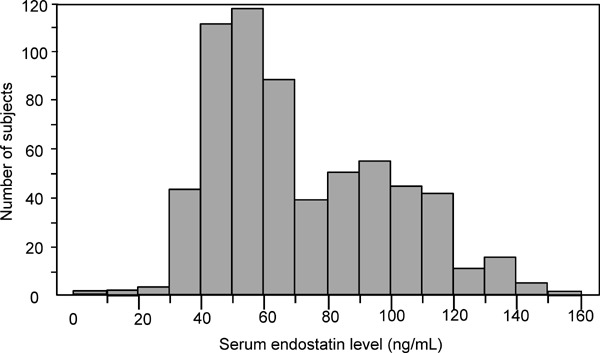

The median endostatin level was 63.7 ng/mL (interquartile range: 49.7–93.2 ng/mL) and the mean endostatin level was 72.2 ng/mL (Fig. 1). The clinical characteristics of the subjects with above (≥ 63.7 ng/mL) and below (< 63.7 ng/mL) median endostatin levels are presented in Table 1. Subjects with above median endostatin had significantly higher carotid IMT than those with below median endostatin (0.71 ± 0.14 vs. 0.65 ± 0.09 mm, P < 0.001). Age, sex, habitual drinking, SBP, DBP, HbA1c, LDL cholesterol level, and eGFR were also significantly different between the participants with above and below median endostatin levels.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of the serum endostatin level of 648 healthy Japanese subjects.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics by serum endostatin level.

| Variable | Below median endostatin (< 63.7 ng/mL, n = 324) | Above median endostatin (≥ 63.7 ng/mL, n = 324) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum endostatin (ng/mL) | 49.7 (43.1–56.3) | 93.2 (77.1–110.2) | < 0.001 |

| Age (years) | 52.4 ± 9.3 | 60.1 ± 10.4 | < 0.001 |

| Man, n (%) | 78 (24.1) | 122 (37.7) | < 0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.5 ± 3.2 | 22.5 ± 2.9 | 0.997 |

| Habitual drinker, n (%) | 42 (13.0) | 80 (24.7) | < 0.001 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 41 (12.8) | 33 (10.2) | 0.324 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 127.4 ± 18.7 | 122.4 ± 17.0 | 0.004 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 75.9 ± 12.7 | 73.4 ± 11.9 | 0.035 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.4 ± 0.5 | 5.5 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 0.009 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 82.3 ± 15.2 | 74.6 ± 13.3 | < 0.001 |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) | 0.26 (0.11–0.58) | 0.28 (0.13–0.64) | 0.089 |

| Carotid IMT (mm) | 0.65 ± 0.09 | 0.71 ± 0.14 | < 0.001 |

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile ranges), or number of subjects (percent) for categorical variables. Overall P values were calculated by unpaired t-test or chi-square test.

HbA1c: hemoglobin A1c, LDL: low density lipoprotein, eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate, hs-CRP: high sensitive C-reactive protein, IMT: intima-media thickness

Association between Endostatin and Carotid Atherosclerosis

Univariate analysis determined that age (r = 0.38, P < 0.001), BMI (r = 0.10, P = 0.008), HbA1c (r = 0.18, P < 0.001), and eGFR (r = −0.11, P = 0.003) were associated with mean carotid IMT. The mean value of carotid IMT was significantly higher for men than women (0.73 vs. 0.65 mm, P < 0.001), habitual drinkers than sometime or non-drinkers (0.73 vs. 0.67 mm, P < 0.001), and current smokers than past or nonsmokers (0.70 vs. 0.67 mm, P = 0.04). The log-transformed endostatin level was also significantly associated with carotid IMT (r = 0.26, P < 0.001). In contrast, SBP, DBP, LDL cholesterol, and log-transformed hs-CRP were not significantly associated with carotid IMT. The log-transformed serum endostatin level was not significantly correlated to carotid IMT in multiple linear regression adjusted for the known covariates of age, sex, BMI, drinking status, smoking status, SBP, DBP, HbA1c, LDL cholesterol, eGFR, and log-transformed hs-CRP (Table 2: Model 1). However, in multivariate analysis with categorized serum endostatin [above (≥ 63.7 ng/mL) vs. below (< 63.7 ng/mL) median serum endostatin level], above median serum endostatin was independently associated with carotid IMT (Table 2: Model 2), but SBP, HbA1c, and LDL cholesterol were not.

Table 2. Multiple linear regression analysis of the association between carotid IMT and serum endostatin.

| Variable | Beta | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1* | Age (years) | 0.27 | < 0.001 |

| Sex (woman = 0, man = 1) | 0.20 | < 0.001 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | −0.01 | 0.894 | |

| Log-transformed serum endostatin | 0.09 | 0.107 | |

| Model 2* | Age (years) | 0.26 | < 0.001 |

| Sex (woman = 0, man = 1) | 0.20 | < 0.001 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | −0.01 | 0.891 | |

| High vs. low serum endostatin group (below median = 0, above median = 1) | 0.11 | 0.029 | |

Beta coefficient and P-value by multiple linear regression.

Adjusted for drinking status, smoking status, systolic BP, diastolic BP, HbA1c, LDL-cholesterol, eGFR, and log-transformed hs-CRP.

IMT: intima-media thickness, BP: blood pressure, LDL: low density lipoprotein, eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate, hs-CRP: high sensitive C-reactive protein

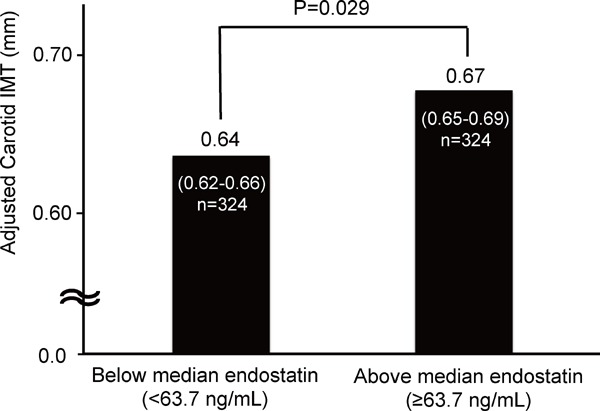

In addition, we evaluated the carotid IMT levels of participants with above (≥ 63.7 ng/mL) and below (< 63.7 ng/mL) median endostatin levels (Fig. 2). Even after adjustment for the known covariates age, sex, BMI, drinking and smoking status, SBP, DBP, HbA1c, LDL cholesterol, eGFR, and log-transformed hs-CRP, the participants with above median endostatin had a higher mean carotid IMT level than did those with below median endostatin (0.67 vs. 0.64 mm, P = 0.029).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the mean carotid IMT of subjects with an above versus below median serum endostatin level.

Data shown as mean carotid IMT and 95% confidence intervals in comparison of the subjects with an above or below median serum endostatin level.

Carotid IMT was adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, drinking status, smoking status, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, HbA1c, LDL cholesterol, eGFR, and log-transformed hs-CRP.

Intergroup differences calculated by the post hoc Tukey's HSD test.

IMT: intima-media thickness, HbA1c: hemoglobin A1c, LDL: low density lipoprotein, eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate, hs-CRP: high sensitive C-reactive protein.

Discussion

The main findings of the present study are that a high serum endostatin level was significantly associated with carotid IMT in this healthy population, but that traditional risk factors for atherosclerosis, such as blood pressure, blood glucose, and blood lipids18), were not. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to show an association between the circulating endostatin level and subclinical atherosclerosis in healthy individuals with low cardiovascular risk.

In our study, the serum endostatin level was associated with subclinical atherosclerosis. Over the past few years, several studies have reported that elevation of the circulating endostatin level is an independent predictor of cardiovascular mortality7), recurrence of cerebrovascular disease4), and the incidence of CKD19). Furthermore, it has been reported that serum endostatin is elevated in patients with acute myocardial infarction20) or CKD21) and that it is associated with endothelial function, urinary albumin, and left ventricular mass6). The results of our study are in accordance with these results. Moreover, because the average age of our participants was 56.7 years and patients with a past history of atherosclerotic disease or who were taking antihypertensive, lipid-lowering, or glucose lowering drugs were excluded, our results also suggest that the serum endostatin level is associated with atherosclerotic diseases of otherwise healthy individuals.

It is known that hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia are traditional risk factors for atherosclerosis. However, in this study, blood pressure, blood glucose, and blood lipids were not independently associated with carotid atherosclerotic change after casting serum endostatin into a multivariate analysis. We had hypothesized that serum endostatin would be more strongly related to early atherosclerotic change than these traditional risks. In addition, because blood pressure, glucose metabolism, and lipid metabolism were almost normal in the population studied, the influence of these traditional risk factors on atherosclerosis might not be strong. Although whether or not traditional risk factors related to atherosclerosis are independently associated with serum endostatin in patients with high cardiovascular risk has not been studied, the impact of serum endostatin on atherosclerosis of patients with cardiovascular risk may be relatively small.

The direct mechanisms related to the serum endostatin level and carotid atherosclerotic changes remain unclear. Endostatin is cleaved from collagen XVIII by proteinases such as MMP-3, -7, -9, -13, -14, and -20, elastase, and cathepsin L22–26). It has also been reported that specific serum MMPs are secreted by foam cells in atherosclerosis lesions27) and that they are positively associated with carotid IMT11, 12). MMP-9 is a key mediator in the development and progression of atherosclerosis28). On the basis of these findings, it is possible that circulating endostatin is elevated in atherosclerosis by degradation of the extracellular matrix through the above proteinases, which would make it a useful marker of atherosclerosis. Although the serum CRP level is also said to predict future cardiovascular events, the association between subclinical atherosclerosis, including carotid IMT and CRP or other markers of inflammation, were not established in multivariate analysis after adjusting for traditional risk factors or BMI29). Furthermore, we found no independent correlation of log-transformed endostatin to carotid IMT in multiple linear regression analysis; thus, serum endostatin may be related to atherosclerosis beyond a certain cut-off point, but not with a linear correlation. Beta error is also possible because the study design for such a low risk group may require a higher number of residents; thus a larger-scale examination will be necessary. On the other hand, endostatin is known to be a potent endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor, and high-dose endostatin treatment can prevent the progression of atherosclerosis27, 30–32). Further studies are required to assess the causal associations between circulating endostatin and atherosclerosis.

There are some limitations to this study. First, the cross-sectional observational design makes it difficult to draw concrete inferences regarding causality between the serum endostatin level and atherosclerosis. Second, all of the subjects of our study were Japanese. Third, non-traditional risk factors associated with carotid IMT, such as thyroid function and monokine induced by gamma interferon, were not explored in the present study33, 34). Finally, we used the results of a single time measurement for our evaluation of serum endostatin. In spite of these limitations, this study is the first to show an association between the serum endostatin level and subclinical atherosclerosis in residents with low cardiovascular risk, based on findings from a large-scale study of a healthy population. We believe that our findings will contribute to the clarification of the usefulness of serum endostatin measurement in the management of cardiovascular diseases in such populations.

We found that the serum endostatin level is independently associated with subclinical atherosclerosis in a Japanese population. Our results indicate that a high circulating endostatin level reflects early atherosclerotic change. Future, longitudinal studies will be necessary to assess the clinical usefulness of the circulating endostatin level as an indicator of future atherosclerotic disease in otherwise healthy populations.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to Drs. Mosaburo Kainuma, Eiichi Ogawa, Kazuhiro Toyoda, Hiroaki Ikezaki, Takeo Hayashi, Takeshi Ihara, Koji Takayama, Fujiko Mitsumoto-Kaseida, Kazuya Ura, Ayaka Komori, Eri Kumade and Masaru Sakiyama from our department for their assistance.

Financial Support

This study was funded by the Japan Multi-institutional Collaborative Cohort Study (J-MICC Study), Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas of Cancer [No. 17015018] and Innovative Areas [No. 221S0001] and by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) [JPSP KAKENHI Grant Number JP 16H06277] from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

Research design: Y Kato and N Furusyo

Data analysis: Y Kato and N Furusyo

Collection and assembly of data: Y Kato, Y Tanaka, T Ueyama, S Yamasaki, M Masayuki, and J Hayashi

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Y Kato and N Furusyo

Final approval of the article: N Furusyo

References

- 1). Seppinen L, Pihlajaniemi T. The multiple functions of collagen XVIII in development and disease. Matrix Biol. 2011; 30: 83-92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). O'Reilly MS, Boehm T, Shing Y, Fukai N, Vasios G, Lane WS, Flynn E, Birkhead JR, Olsen BR, Folkman J. Endostatin: an endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis and tumor growth. Cell. 1997; 88: 277-285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Skovseth DK, Veuger MJ, Sorensen DR, De Angelis PM, Haraldsen G. Endostatin dramatically inhibits endothelial cell migration, vascular morphogenesis, and perivascular cell recruitment in vivo. Blood. 2005; 105: 1044-1051. Erratum in: Blood. 2009; 114: 227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Arenillas JF, Alvarez-Sabín J, Montaner J, Rosell A, Molina CA, Rovira A, Ribó M, Sánchez E, Quintana M. Angiogenesis in symptomatic intracranial atherosclerosis: predominance of the inhibitor endostatin is related to a greater extent and risk of recurrence. Stroke. 2005; 36: 92-97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Wątorek E, Paprocka M, Duś D, Kopeć W, Klinger M. Endostatin and vascular endothelial growth factor: potential regulators of endothelial progenitor cell number in chronic kidney disease. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2011; 121: 296-301 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Carlsson AC, Ruge T, Sundström J, Ingelsson E, Larsson A, Lind L, Arnlöv J. Association between circulating endostatin, hypertension duration, and hypertensive targetorgan damage. Hypertension. 2013; 62: 1146-1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Ärnlöv J, Ruge T, Ingelsson E, Larsson A, Sundström J, Lind L. Serum endostatin and risk of mortality in the elderly: findings from 2 community-based cohorts. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013; 33: 2689-2695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Nezu T, Hosomi N, Aoki S, Matsumoto M. Carotid Intima-Media Thickness for Atherosclerosis. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2016; 23: 18-31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Lorenz MW, Markus HS, Bots ML, Rosvall M, Sitzer M. Prediction of clinical cardiovascular events with carotid intima-media thickness: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Circulation. 2007; 115: 459-467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Shimizu M, Furusyo N, Mitsumoto F, Takayama K, Ura K, Hiramine S, Ikezaki H, Ihara T, Mukae H, Ogawa E, Toyoda K, Kainuma M, Murata M, Hayashi J. Subclinical carotid atherosclerosis and triglycerides predict the incidence of chronic kidney disease in the Japanese general population: results from the Kyushu and Okinawa Population Study (KOPS). Atherosclerosis. 2015; 238: 207-212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Gaubatz JW, Ballantyne CM, Wasserman BA, He M, Chambless LE, Boerwinkle E, Hoogeveen RC. Association of circulating matrix metalloproteinases with carotid artery characteristics: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Carotid MRI Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010; 30: 1034-1042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Söder PO, Meurman JH, Jogestrand T, Nowak J, Söder B. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 in blood as markers for early atherosclerosis in subjects with chronic periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 2009; 44: 452-458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Ikezaki H, Furusyo N, Okada K, Ihara T, Hayashi T, Ogawa E, Kainuma M, Murata M, Hayashi J. The utility of urinary myo-inositol as a marker of glucose intolerance. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014; 103: 88-96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). Furusyo N, Koga T, Ai M, Otokozawa S, Kohzuma T, Ikezaki H, Schaefer EJ, Hayashi J. Utility of glycated albumin for the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus in a Japanese population study: results from the Kyushu and Okinawa Population Study (KOPS). Diabetologia. 2011; 54: 3028-3036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Shimizu M, Furusyo N, Tanaka Y, Kato Y, Mitsumoto-Kaseida F, Takayama K, Ura K, Hiramine S, Hayashi T, Ikezaki H, Ihara T, Mukae H, Ogawa E, Toyoda K, Kainuma M, Murata M, Hayashi J. The relation of postprandial plasma glucose and serum endostatin to the urinary albumin excretion of residents with prediabetes: results from the Kyushu and Okinawa Population Study (KOPS). Int Urol Nephrol. 2016; 48: 851-857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16). Matsuo S, Imai E, Horio M, Yasuda Y, Tomita K, Nitta K, Yamagata K, Tomino Y, Yokoyama H, Hishida A, Collaborators developing the Japanese equation for estimated GFR . Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009; 53: 982-992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). Yanase T, Nasu S, Mukuta Y, Shimizu Y, Nishihara T, Okabe T, Nomura M, Inoguchi T, Nawata H. Evaluation of a new carotid intima-media thickness measurement by B-mode ultrasonography using an innovative measurement software, intimascope. Am J Hypertens. 2006; 19: 1206-1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). Qin G, Luo L, Lv L, Xiao Y, Tu J, Tao L, Wu J, Tang X, Pan W. Decision tree analysis of traditional risk factors of carotid atherosclerosis and a cutpoint-based prevention strategy. PLoS One. 2014; 9: e111769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). Ruge T, Carlsson AC, Larsson TE, Carrero JJ, Larsson A, Lind L, Ärnlöv J. Endostatin level is associated with kidney injury in the elderly: findings from two community-based cohorts. Am J Nephrol. 2014; 40: 417-424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Seko Y, Fukuda S, Nagai R. Serum levels of endostatin, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) in patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing early reperfusion therapy. Clin Sci (Lond). 2004; 106: 439-442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21). Chen J, Hamm LL, Kleinpeter MA, Husserl F, Khan IE, Chen CS, Liu Y, Mills KT, He C, Rifai N, Simon EE, He J. Elevated plasma levels of endostatin are associated with chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2012; 35: 335-340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22). Wen W, Moses MA, Wiederschain D, Arbiser JL, Folkman J. The generation of endostatin is mediated by elastase. Cancer Res. 1999; 59: 6052-6056 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Felbor U, Dreier L, Bryant RA, Ploegh HL, Olsen BR, Mothes W. Secreted cathepsin L generates endostatin from collagen XVIII. EMBO J. 2000; 19: 1187-1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). Ferreras M, Felbor U, Lenhard T, Olsen BR, Delaissé J. Generation and degradation of human endostatin proteins by various proteinases. FEBS Lett. 2000; 486: 247-251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25). Chang JH, Javier JA, Chang GY, Oliveira HB, Azar DT. Functional characterization of neostatins, the MMP-derived, enzymatic cleavage products of type XVIII collagen. FEBS Lett. 2005; 579: 3601-3606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26). Heljasvaara R, Nyberg P, Luostarinen J, Parikka M, Heikkilä P, Rehn M, Sorsa T, Salo T, Pihlajaniemi T. Generation of biologically active endostatin fragments from human collagen XVIII by distinct matrix metalloproteases. Exp Cell Res. 2005; 307: 292-304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27). Mao W, Kong J, Dai J, Huang ZQ, Wang DZ, Ni GB, Chen ML. Evaluation of recombinant endostatin in the treatment of atherosclerotic plaques and neovascularization in rabbits. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2010; 11: 599-607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28). Ma Y, Yabluchanskiy A, Hall ME, Lindsey ML. Using plasma matrix metalloproteinase-9 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 to predict future cardiovascular events in subjects with carotid atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2014; 232: 231-233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29). Nagasawa SY, Ohkubo T, Masaki K, Barinas-Mitchell E, Miura K, Seto T, El-Saed A, Kadowaki T, Willcox BJ, Edmundowicz D, Kadota A, Evans RW, Kadowaki S, Fujiyoshi A, Hisamatsu T, Bertolet MH, Okamura T, Nakamura Y, Kuller LH, Ueshima H, Sekikawa A, ERAJUNP Study Group Associations between Inflammatory Markers and Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Middle-aged White, Japanese-American and Japanese Men: The ERAJUMP Study. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2015; 22: 590-598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30). Moulton KS, Heller E, Konerding MA, Flynn E, Palinski W, Folkman J. Angiogenesis inhibitors endostatin or TNP-470 reduce intimal neovascularization and plaque growth in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 1999; 99: 1726-1732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31). Greene AK, Kim S, Rogers GF, Fishman SJ, Olsen BR, Mulliken JB. Risk of vascular anomalies with Down syndrome. Pediatrics. 2008; 121: e135-e140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32). Xu X, Mao W, Chai Y, Dai J, Chen Q, Wang L, Zhuang Q, Pan Y, Chen M, Ni G, Huang Z. Angiogenesis Inhibitor, Endostar, Prevents Vasa Vasorum Neovascularization in a Swine Atherosclerosis Model. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2015; 22: 1100-1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33). Yu HT, Lee J, Shin EC, Park S. Significant Association between Serum Monokine Induced by Gamma Interferon and Carotid Intima Media Thickness. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2015; 22: 816-822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34). Zhou Y, Zhao L, Wang T, Hong J, Zhang J, Xu B, Huang X, Xu M, Bi Y. Free Triiodothyronine Concentrations are Inversely Associated with Elevated Carotid Intima-Media Thickness in Middle-Aged and Elderly Chinese Population. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2016; 23: 216-224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]