Abstract

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) catalyze the cleavage of ubiquitin from target proteins. Ubiquitin is post‐translationally attached to proteins and serves as an important regulatory signal for key cellular processes. In this study, novel activity‐based probes to study DUBs were synthesized that comprise a ubiquitin moiety and a novel disulfide warhead at the C‐terminus. These reagents can bind DUBs covalently by forming a disulfide bridge between the active‐site cysteine residue and the ubiquitin‐based probe. As disulfide bridges can be broken by the addition of a reducing agent, these novel ubiquitin reagents can be used to capture and subsequently release catalytically active DUBs, whereas existing capturing agents bind irreversibly. These novel reagents allow for the study of these enzymes in their active state under various conditions.

Keywords: activity-based protein profiling, disulfide exchange, enzyme activity, post-translational modifications, ubiquitin

The modification of target proteins with ubiquitin (Ub), a process called ubiquitination, is a key post‐translational event that regulates a wide range of cellular processes. Ub is a highly conserved 76 amino acid protein, which is conjugated to proteins by the formation of an isopeptide bond between the C‐terminus of Ub and a lysine residue or the N‐terminus of a target protein. Ub can also be coupled to other Ub moieties to form various polyubiquitin chains. Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) catalyze the cleavage of these isopeptide bonds, thereby regulating the ubiquitination of target proteins. The human genome encodes about 80 active DUBs, which can be classified into five classes of cysteine (Cys) proteases and one class of metalloprotease DUBs.1 As the function of many DUBs is still unknown, studying these enzymes in their active state, either in isolation or as part of a protein complex, is of great importance. Existing reagents to study the activity of DUBs include cleavable Ub‐containing substrates2 and covalently binding activity‐based probes (ABPs)3 that react with the active‐site Cys residue. The latter have been used in activity profiling, inhibitor screening, and DUB identification.3b However, these ABPs bind irreversibly to the active site of the DUB, rendering them inactive. In this study, we developed a Ub‐based ABP with a novel warhead that captures DUBs from cell extracts and allows for their release in an active state (Scheme 1).

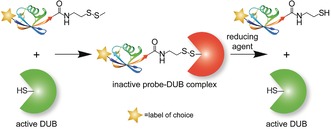

Scheme 1.

Binding of disulfide probes to DUBs and subsequent release by mild cleavage with a reducing agent.

In our probe design, we intended to use reagents that can reversibly modify thiols as Ub‐based ABPs react with the active‐site Cys residue. Many such reagents, if not all, are highly reactive, and thus unspecific towards Cys residues in proteins. Therefore, previous methods to modify specific cysteines relied on the mutation of non‐target cysteines to prevent their modification. For example, GlcNAc‐methylthiosulfonate has been used to modify proteins with GlcNAc moieties on specific cysteines.4 In these proteins, undesirable Cys residues were replaced by serine residues. Other known reagents used for the modification of Cys residues are disulfides (R′−S−S−R′′), which are less reactive. The Cys thiolate attacks the disulfide bond, and subsequently a new asymmetric disulfide is formed in a process named thiol‐specific exchange. Chatterjee and co‐workers have used this approach to generate a ubiquitinated histone complex.5 They modified a Cys residue that was introduced in histone 2B by first activating the thiol using 2,2′‐dithiobis(5‐nitropyridine) to form a disulfide. Subsequently, a Ub moiety carrying a C‐terminal aminoethanethiol group was coupled. We exploited the thiol‐specific exchange for the design of a reversible warhead for our novel DUB ABP. We postulated that a Ub moiety would direct our disulfide ABP to the active‐site cysteine in DUBs. The glycine residue at position 76 of Ub was replaced with methyl disulfide as a warhead (Scheme 2). We hypothesized that this disulfide moiety would undergo thiol‐specific exchange with the active‐site Cys residue in DUBs, thereby forming a covalent disulfide bond (Scheme 1). The addition of a mild reducing agent would then be able to break this disulfide bond and release enzymatically active DUBs.

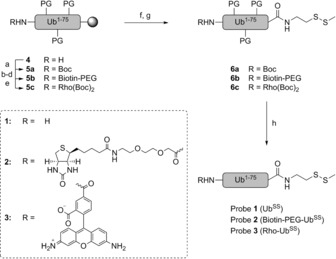

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of disulfide probes 1 (UbSS), 2 (biotin–PEG–UbSS), and 3 (Rho–UbSS). Ubiquitin lacking the C‐terminal glycine (Ub1–75) was synthesized on resin (4). The N‐terminus was modified under various conditions (a–e). a) Boc2O, DiPEA, NMP; b) PyBOP, DiPEA, (8‐Fmoc‐amino)‐3,6‐dioxaoctanoic acid, NMP; c) piperidine, NMP: d) biotin, HBTU, HOBt, DiPEA, NMP; e) PyBOP, DiPEA, N,N′‐Boc‐protected 5‐carboxyrhodamine 110 (Rho),6 NMP. After cleavage from the resin (f), the C‐terminus was modified with an S−SMe group (g). Global deprotection yielded the final probes (h). f) HFIP, DCM; g) PyBOP, Et3N, 2‐(methyldisulfanyl)ethan‐1‐amine, DCM; h) TFA/H2O/iPr3SiH/PhOH. See the Supporting Information for details. DCM=dichloromethane, DiPEA=N,N‐diisopropylethylamine, HBTU=O‐(benzotriazol‐1‐yl)‐N,N,N′,N′‐tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate, HFIP=hexafluoroisopropanol, HOBt=1‐hydroxybenzotriazole, NMP=N‐methyl‐2‐pyrrolidone, PyBOP=benzotriazol‐1‐yl‐oxytripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate, TFA=trifluoroacetic acid.

Three variants of the Ub‐based disulfide probe with different N‐terminal modifications were synthesized; one with a free N‐terminus (1, UbSS), one with an N‐terminal biotin affinity tag linked via a poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) spacer (2, biotin–PEG–UbSS), and one with the fluorescent dye 5‐carboxyrhodamine 110 (3, Rho–UbSS; Scheme 2; see also the Supporting Information, Figure S1 a). Ub1–75 was synthesized by total chemical solid‐phase synthesis.3c, 7 The N‐terminus of Ub1–75 (4) was subsequently modified with a Boc group (5 a), modified with a PEG spacer and a biotin moiety (5 b), or modified with N,N′‐Boc‐protected 5‐carboxyrhodamine 1106, 8 (5 c). The peptides were then cleaved from the resin using hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP). 2‐(Methyldisulfanyl)ethan‐1‐amine was coupled to the C‐terminus of Ub1–75 as the warhead (6 a–6 c). 2‐(Methyldisulfanyl)ethan‐1‐amine was synthesized as described previously.9 TFA‐mediated deprotection and purification yielded probes 1, 2, and 3 (Scheme 2 and Figure S1 a). The probes were analyzed by SDS‐PAGE and LC‐MS (Figure S1).

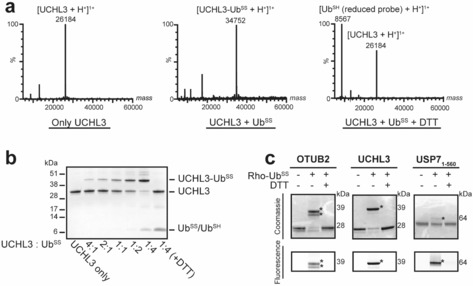

To test whether our novel Ub‐based DUB probes containing the disulfide warhead are able to bind to DUBs in vitro, we incubated the DUB UCHL3 with the probes UbSS or biotin–PEG–UbSS and followed the reactions by LC‐MS and gel electrophoresis (Figures 1 a, b and S2). We observed an increase in the mass of UCHL3 corresponding to the binding of one probe moiety, which confirmed that these probes are indeed able to react covalently. At higher concentrations of UbSS and biotin–PEG–UbSS, additional bands were observed on the gel, which may represent binding of the probes to other Cys residues in UCHL3 although labeling is minimal as shown by LC‐MS analysis. To determine whether the formed probe–DUB complex could be reduced, we incubated the reaction mixture with 10 mm dithiothreitol (DTT). As shown in Figures 1 a, b and S2, the probe–UCHL3 complexes are completely reduced, yielding unlabeled UCHL3 and reduced probe (UbSH). To examine whether Ub‐based disulfide probes can bind to DUBs from other classes, we incubated fluorescently labeled UbSS (3, Rho–UbSS) with UCHL3, OTUB2, or USP7 TRAF/catalytic domain (USP71–560), and monitored the labeling by fluorescence scanning of the non‐reducing SDS‐PAGE gel (Figure 1 c). Rho–UbSS bound to all three DUBs as fluorescent bands with the expected molecular weights were observed after labeling. In addition, upwards shifts were observed after staining the gel with Coomassie Brilliant Blue, corresponding to the binding of one probe moiety to the DUBs. DTT treatment of the probe–DUB complex resulted in complete reduction and release of the reduced probe Rho–UbSH from the DUB.

Figure 1.

a) Binding of UbSS to UCHL3 monitored by mass spectrometry at a molar ratio of UCHL3/UbSS=1:4. Treatment with DTT shows complete reduction of the complex. Unlabeled UCHL3 is shown as a reference. Additional peaks are detailed in Figure S2. b) Binding of UbSS to UCHL3 at different UCHL3/UbSS molar ratios. Treatment with DTT releases reduced probe (UbSH) from the UbSS–UCHL3 complex. Analysis was done by SDS‐PAGE and Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining. c) Binding of the fluorescent probe Rho–UbSS to OTUB2, UCHL3, and the TRAF/catalytic domain of USP7 (USP71–560). Analysis was done by SDS‐PAGE and Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining or in‐gel fluorescence scanning. DUBs labeled with Rho–UbSS are indicated with an asterisk (*).

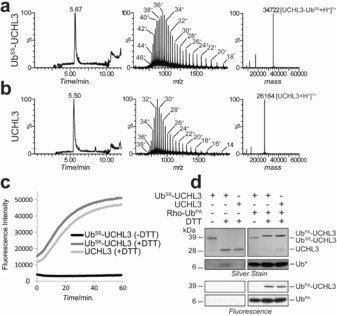

To determine whether the activity of a DUB could be restored after reduction, we first reacted UCHL3 with UbSS and purified the complex by anion exchange chromatography (Figure 2 a). Unlabeled UCHL3 was purified using the same procedure (Figure 2 b). The UbSS–UCHL3 complex was then either left as is or treated with DTT, after which the enzymatic activity was monitored using a fluorogenic activity assay. In this assay, Ub–Rhodamine110 (Ub–Rho110) is cleaved, which releases fluorescent Rho110. In the absence of DTT, no cleavage was observed (Figure 2 c). However, upon addition of DTT, Ub–Rho110 was cleaved with similar kinetics as observed with unlabeled UCHL3, indicating that the disulfide bond in the UbSS–UCHL3 complex was reduced, and the activity could be completely restored. The activity of UCHL3 was also monitored using the fluorescent Ub–propargylamide (PA) DUB ABP Rho–Ub–PA.3d Fluorescent bands corresponding to UCHL3 bound to Rho–Ub–PA were observed for both unlabeled UCHL3 and DTT‐treated UbSS–UCHL3 complexes, but not for untreated UbSS–UCHL3 complexes (Figure 2 d). Correspondingly, upward shifts in the silver‐stained gel were observed for both UCHL3 and DTT‐treated UbSS–UCHL3 complex. UCHL3 released from the UbSS–UCHL3 complex after reduction showed similar labeling with Rho–Ub–PA as UCHL3 alone, suggesting that released UCHL3 regains full activity.

Figure 2.

Analytical LC‐MS profile of a) UbSS–UCHL3 complex and b) untreated UCHL3, purified by anion exchange chromatography. Additional peaks are detailed in Figure S3. c) The enzymatic activity of untreated and DTT‐treated purified UbSS–UCHL3 complex and purified unlabeled UCHL3 was monitored using a Ub–Rho110 fluorogenic DUB activity assay. d) The enzymatic activity of untreated and DTT‐treated purified UbSS–UCHL3 complex and purified unlabeled UCHL3 was monitored using the fluorescent DUB probe Rho–Ub–PA.3d Proteins were resolved by non‐reducing SDS‐PAGE and visualized by fluorescence scanning or silver staining. Ub* indicates reduced disulfide probe UbSH (left panel) or Rho–Ub–PA and UbSH (right panel).

To validate that disulfide probes can also bind to DUBs in cell extract, we tested whether UbSS can inhibit the binding of the fluorescent DUB ABP TMR–Ub–PA.3d Cell extracts from HeLa cells were pre‐incubated with 1 μm of UbSS, followed by incubation with 1 μm of TMR–Ub–PA. As shown in Figure 3 a, UbSS almost completely inhibited the labeling of DUBs by TMR–Ub–PA. The presence of DTT in the assay did allow for the labeling of DUBs with the TMR–Ub–PA probe, which suggests that UbSS–DUB complexes are readily released or not formed in the presence of reducing agent. To visualize the binding of UbSS to specific DUBs in cell extract, we overexpressed GFP fusions of the DUBs OTUB1 (Figures 3 b and S4 a), OTUB2 (Figure S4 b), and USP8 (Figure S4 c). Cell extracts were made and incubated with UbSS or Ub–PA as a positive control. We visualized labeling by non‐reducing SDS‐PAGE followed by anti‐GFP immunoblotting. Labeling with one UbSS moiety was observed for all three GFP‐fused DUBs, illustrated by a shift in migration on gel. Moreover, catalytic cysteine mutants showed minimal labeling (Figure S4), which corroborated that the active‐site cysteine is the main site for modification.

Figure 3.

a) Competition experiment in which HeLa cell extract was incubated with UbSS, followed by DUB labeling with fluorescent TMR–Ub–PA3d in the presence or absence of DTT. Labeled proteins were visualized using in‐gel fluorescence scanning. b) Binding of UbSS or Ub–PA to overexpressed GFP–OTUB1. GFP–OTUB1–Ub* indicates GFP–OTUB1 bound to either UbSS (lane 2) or Ub–PA probe (lane 3). Preincubation with N‐methyl maleimide (NMM) was used as a negative control (lane 4). GFP–OTUB1 was visualized using anti‐GFP immunoblotting. Actin immunoblotting was used as a loading control. c) A HeLa cell extract was incubated with biotin‐labeled UbSS, and reacted DUBs were captured on neutravidin resin. DUBs were released from the resin using DTT. Eluted DUBs and DUBs in the input cell extract were labeled with the fluorescently labeled ABP TMR–Ub–PA3d and visualized using in‐gel fluorescence scanning.

To determine whether we can capture and release active DUBs from cell extract on resin, we incubated HeLa cell extracts with biotin–PEG–UbSS. The mixture was then allowed to bind to neutravidin resin. After washing of the resin, bound DUBs were eluted with the reducing agents DTT, TCEP, β‐mercaptoethanol, or Cys (Figures 3 c and S5). TMR–Ub–PA was added to the eluted fractions to visualize active DUBs by in‐gel fluorescence scanning. The majority of DUBs that could be labeled in cell extract could also be labeled after elution with reducing agent. Notably, the 56 kDa DUB USP14 (65 kDa after binding of TMR‐Ub‐PA)3a,3c,3f, 10 was not retrieved or not active after elution. This is likely due to the absence of proteasome after washing the resin. USP14 is known to be activated upon association with the proteasome.3a, 11 Almost no active DUBs were eluted when no reducing agents were used. Thus active DUBs can be caught using our biotin–PEG–UbSS probe and specifically released under mild reducing conditions.

In conclusion, we have developed a novel type of Ub‐based activity‐based probe containing a methyl disulfide warhead that binds to DUBs by means of active‐site‐specific disulfide exchange. We have shown that we can capture DUBs from cell extract on resin, and elute them by using reducing agents. The importance of this probe lies in its ability to isolate active DUBs from their natural environment as cell‐specific post‐translational modifications may be present that regulate DUB activity. Our reversible probe can thus be used to isolate active DUBs or DUB–protein complexes from cells to study the activity of specific DUBs in in vitro deubiquitination assays. To the best of our knowledge, the DUB probes presented here are the first probes that can capture a specific family of enzymes and release active enzymes under mild conditions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a VICI grant (to H.O.) from The Netherlands Foundation for Scientific Research (NWO). We thank Dris el Atmioui and Henk Hilkmann for the solid‐phase synthesis of ubiquitin, the NKI protein facility for the expression and purification of OTUB2, Alexander Fish from the NKI protein facility for help with anion‐exchange purification of UbSS–UCHL3 and UCHL3, and Paul Geurink and Titia Sixma for advice. We thank Robbert Kim for providing USP71–560, Remco Merkx for providing Rho–Ub–PA and UCHL3, Gerbrand van der Heden‐van Noort for providing Ub–PA and TMR–Ub–PA, and Ilana Berlin for providing the GFP‐fused DUB constructs.

A. de Jong, K. Witting, R. Kooij, D. Flierman, H. Ovaa, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 12967.

Contributor Information

Katharina Witting, http://www.ovaalab.nl.

Prof. Dr. Huib Ovaa, Email: H.Ovaa@lumc.nl.

References

- 1.

- 1a. Reyes-Turcu F. E., Ventii K. H., Wilkinson K. D., Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009, 78, 363–397; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Clague M. J., Heride C., Urbe S., Trends Cell Biol. 2015, 25, 417–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Geurink P. P., El Oualid F., Jonker A., Hameed D. S., Ovaa H., ChemBioChem 2012, 13, 293–297; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Mevissen T. E., Hospenthal M. K., Geurink P. P., Elliott P. R., Akutsu M., Arnaudo N., Ekkebus R., Kulathu Y., Wauer T., El Oualid F., Freund S. M., Ovaa H., Komander D., Cell 2013, 154, 169–184; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2c. Dang L. C., Melandri F. D., Stein R. L., Biochemistry 1998, 37, 1868–1879; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2d. Hassiepen U., Eidhoff U., Meder G., Bulber J. F., Hein A., Bodendorf U., Lorthiois E., Martoglio B., Anal. Biochem. 2007, 371, 201–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.

- 3a. Borodovsky A., Kessler B. M., Casagrande R., Overkleeft H. S., Wilkinson K. D., Ploegh H. L., EMBO J. 2001, 20, 5187–5196; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3b. Borodovsky A., Ovaa H., Kolli N., Gan-Erdene T., Wilkinson K. D., Ploegh H. L., Kessler B. M., Chem. Biol. 2002, 9, 1149–1159; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3c. de Jong A., Merkx R., Berlin I., Rodenko B., Wijdeven R. H., El Atmioui D., Yalcin Z., Robson C. N., Neefjes J. J., Ovaa H., ChemBioChem 2012, 13, 2251–2258; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3d. Ekkebus R., van Kasteren S. I., Kulathu Y., Scholten A., Berlin I., Geurink P. P., de Jong A., Goerdayal S., Neefjes J., Heck A. J., Komander D., Ovaa H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 2867–2870; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3e. Ward J. A., McLellan L., Stockley M., Gibson K. R., Whitlock G. A., Knights C., Harrigan J. A., Jacq X., Tate E. W., ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 3268–3272; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3f. Flierman D., van der Heden van Noort G. J., Ekkebus R., Geurink P. P., Mevissen T. E., Hospenthal M. K., Komander D., Ovaa H., Cell Chem. Biol. 2016, 23, 472–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van Kasteren S. I., Kramer H. B., Jensen H. H., Campbell S. J., Kirkpatrick J., Oldham N. J., Anthony D. C., Davis B. G., Nature 2007, 446, 1105–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chatterjee C., McGinty R. K., Fierz B., Muir T. W., Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010, 6, 267–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Geurink P. P., van Tol B. D., van Dalen D., Brundel P. J., Mevissen T. E., Pruneda J. N., Elliott P. R., van Tilburg G. B., Komander D., Ovaa H., ChemBioChem 2016, 17, 816–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. El Oualid F., Merkx R., Ekkebus R., Hameed D. S., Smit J. J., de Jong A., Hilkmann H., Sixma T. K., Ovaa H., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 10149–10153; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2010, 122, 10347–10351. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bonnet D., Ilien B., Galzi J. L., Riche S., Antheaune C., Hibert M., Bioconjugate Chem. 2006, 17, 1618–1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Borg L. z., Lee D., Lim J., Bae W. K., Park M., Lee S., Lee C., Char K., Zentel R., J. Mater. Chem. C 2013, 1, 1722–1726. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Altun M., Kramer H. B., Willems L. I., McDermott J. L., Leach C. A., Goldenberg S. J., Kumar K. G., Konietzny R., Fischer R., Kogan E., Mackeen M. M., McGouran J., Khoronenkova S. V., Parsons J. L., Dianov G. L., Nicholson B., Kessler B. M., Chem. Biol. 2011, 18, 1401–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee B. H., Lee M. J., Park S., Oh D. C., Elsasser S., Chen P. C., Gartner C., Dimova N., Hanna J., Gygi S. P., Wilson S. M., King R. W., Finley D., Nature 2010, 467, 179–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary