Abstract

Accelerating progress to improve complementary feeding of young children is a global priority. Strengthening monitoring through government information systems may increase the quality and implementation of infant and young child feeding (IYCF) programs. Monitoring is necessary for the effective implementation of programs as it allows program managers to assess program performance, identify problems, and take corrective action. Program descriptions and conceptual models explain how program inputs and activities should lead to outputs and outcomes, and ultimately public health impact; thus, they are critical tools when designing effective IYCF programs and monitoring systems as these descriptions and conceptual models form the basis for the program and are key for developing the monitoring system, indicators, and tools. Despite their importance, many programs do not have these documented, nor monitoring plans, limiting their ability to design effective programs and monitoring systems. Once in place, it is important to periodically review the monitoring system to confirm it still appropriately meets stakeholder needs and the data are being used to inform decision‐making, and to make program adjustments as the monitoring focus, resources, or capacity may change during the program lifecycle. Including priority indicators of IYCF practices and counseling indicators in the government information systems may strengthen IYCF programs when the indicators are contextualized to the government IYCF program, capacity, and setting, and the indicators are used for decision‐making and program improvement.

Keywords: child feeding, complementary feeding, diet, infant and child nutrition, monitoring and evaluation, programming

1. INTRODUCTION

Monitoring is essential for the effective implementation of infant and young child feeding (IYCF) programs as it allows program managers to assess program performance, identify problems, and take corrective action. UNICEF's Nutridash surveillance system assesses the scope, scale, and implementation of IYCF programs globally (UNICEF, 2014). In 2013, 80 countries were implementing IYCF programs but not all carried out monitoring. A Nutridash composite indicator that examined monitoring of IYCF indicators in the health management information system (HMIS) and at the community level found that 34% of countries scored “insufficient” and another 34% scored “fair,” leading to the conclusion that a large percentage of IYCF programs need to strengthen their monitoring (UNICEF, 2014). To provide information that may be useful for those trying to strengthen monitoring of country IYCF programs and accelerate progress on complementary feeding for young children, the focus of this commentary is to review some basic considerations for designing monitoring systems for public health programs and tools, sources of data potentially useful for IYCF programs, and to discuss issues with indicators for routine monitoring through government systems.

Key messages.

A program description and conceptual model explains how program inputs and activities should lead to outputs and outcomes, and ultimately public health impact. This forms the basis for the program and developing the monitoring system, indicators, and tools.

All programs need internal monitoring to implement effective programs, and government information systems are key sources.

Tools and frameworks exist to guide the development of monitoring systems for complementary feeding programs.

Complementary feeding indicators contextualized to the government program, capacity, and setting that are useful for decision‐making, and program improvement can be used to strengthen complementary feeding programs for young children.

2. MONITORING PUBLIC HEALTH PROGRAMS

Program monitoring is the “ongoing process of collecting, analyzing, interpreting and reporting indicators, to compare how well a program is being executed against expected objectives. (Home Fortification Technical Advisory Group [HF‐TAG], 2013).” Monitoring may be carried out for program development, implementation and improvement, or maintenance, and should happen continuously throughout all stages of the program lifecycle in order for programs to achieve public health impact. Monitoring may employ quantitative or qualitative methods and will vary depending on the design, focus, and purpose.

Internal monitoring is necessary for all programs and refers to those data and systems that are managed by program staff, or to which the staff have access; there is a close intersection of program management and internal monitoring as these data are used to plan, assess performance, and make needed program adjustments. Typical examples of these types of data and systems include government information systems, such as HMIS, logistics management information system, or health clinic records. External monitoring data are collected and managed by those independent of program staff. With external monitoring, the expectation is that those collecting and analyzing the information may be more objective than with internal monitoring systems, where program staff may be assessing their own performance. On a practical level, it is also potentially more feasible to have an external organization carry out more complex and time‐consuming methods via external monitoring than is feasible with internal monitoring (e.g., a population‐based cross‐sectional survey carried out by an external contractor). When specific issues with program performance occur or to help explain why they occur, it might be necessary to collect additional focused and specialized information to better understand the question, issue, or problem and identify appropriate solutions. Specialized data collection may be done by program staff or those external to the program. Recognizing that resources and capacity may vary significantly across and within countries, it is common practice for IYCF programs to be implemented through government health facilities and for monitoring to center exclusively on the inclusion of a few indicators collected through the internal government information systems, such as the HMIS.

3. PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONS, CONCEPTUAL MODELS, AND MONITORING FRAMEWORKS

A critical first step in designing a public health program and monitoring system is to describe the program and develop a conceptual model that explains how program inputs and activities are expected to lead to outputs and outcomes, ultimately resulting in public health impact. Although it may seem obvious to state the need for these descriptions, unfortunately it is not uncommon for IYCF programs to lack these documents, leaving it unclear how the program and monitoring systems are supposed to work in the country context. Further, although programs are often labelled “infant and young child feeding” programs, in some countries there has been more focus on policies and programs to improve breastfeeding but not a similar attention to complementary feeding (Lutter et al. 2013), which may result in more IYCF program activities focused on breastfeeding, especially for infants 0–6 months of age, as opposed to complementary feeding and continued breastfeeding for infants and children 6–23 months of age. To develop the IYCF monitoring plan and indicators, descriptions and conceptual models should be detailed enough so that these types of contextual matters related to the expected processes, focus, intensity, delivery, resources, and supervision of breastfeeding and complementary feeding activities are explicit and clearly show how they should ultimately relate to expected outcomes.

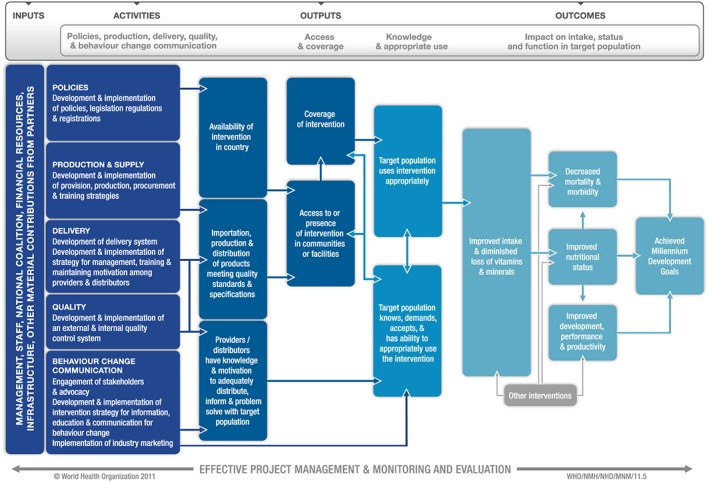

There are various tools, such as a logic model, program impact pathway, or logical framework, that can be used to support developing these descriptions and conceptual models (e.g., Figure 1; Habicht & Pelto, 2014; Population Services International [PSI], 2000), and any one or several simultaneously can be used for this purpose. The important issue is having a description of the program and conceptual model that explains the expected processes accurately and with sufficient detail that they are useful for program staff and other stakeholders. Monitoring frameworks are tools to guide the design, implementation, and evaluation of monitoring systems; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Framework for Program Evaluation in Public Health is one example of a tool that lays out this process in six steps (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 1999).

Figure 1.

World Health Organization/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention logic model for micronutrient interventions in public health. http://www.who.int/vmnis/toolkit/logic_model/en/ accessed 18 March 2016

IYCF programs should ultimately have a monitoring plan that describes the processes, procedures, and resources to collect, manage, analyze, disseminate, and use monitoring data. Many IYCF programs are implemented through government health facilities, sometimes in conjunction with volunteers in communities, and the monitoring system only includes a few IYCF indicators integrated into government information systems. These monitoring systems largely follow the monitoring plan of the government HMIS so that data are collected through health facilities, who send this information to higher administrative levels (e.g., the district health office) in monthly reports; the data are analyzed and reviewed, and reports are sent back to the reporting facilities, and summaries are sent periodically (e.g., quarterly) to higher administrative/central levels for review, feedback, and follow up. Programs that rely on community volunteers to deliver IYCF counseling, messages, referrals, or other supportive practices may report difficulties collecting monitoring data from volunteers because of limitations related to illiteracy or motivation to turn in logs and reports (e.g., no payment of transportation fees to travel to the health facility for monthly meetings to turn in logs). Generally, only IYCF programs that receive additional project‐specific funding from government, partners, or donors carry out monitoring activities beyond those collected in the HMIS. While IYCF projects that receive additional funding may perform better due to additional program and monitoring resources at a project level, it is important to consider that resources and capacity vary across and within countries and to keep this in mind when planning for the expected final scale of the program, especially if additional funds to support monitoring will not be available when fully at scale.

It is expected that managers at all levels (e.g., facility, district, and central levels) will routinely receive and use monitoring reports for program management, correction, and improvement. In addition, once a monitoring system is developed, it is important to go through a “reality check” with government IYCF program staff and other stakeholders (such as the national nutrition working group or national IYCF working group) to make sure what is designed is being implemented as planned and is scalable (if the program and monitoring system are expected to expand to other areas), and also to periodically review the program performance (e.g., every 6 months or annually). Reviews of the program and monitoring system should confirm that the system continues to meet program staff and stakeholder needs and that the focus is still relevant and appropriate; that the indicators collected are useful, feasible, and collected with acceptable quality; and that the data are analyzed and reported, and used to inform decision‐making and program adjustments. Improving complementary feeding practices is complex, and feeding guidance changes with the age of the child (UNICEF, 2011), which may increase the risk that what is planned is not routinely carried out with fidelity as expected across all settings, especially in lower resource and capacity settings. For example, a district only focuses on promotion of exclusive breastfeeding for infants less than 6 months of age and no other parts of the IYCF package; there is a shortage of funds to pay monthly transportation fees for volunteers and reporting of community‐level activities stops; or the IYCF program is not being implemented at all in one or more districts. When programs are not implemented as planned, monitoring data may not be systematically collected and reported as planned either (e.g., no need to spend resources to monitor a program that is not being implemented). Periodic annual or biannual reviews with program staff and stakeholders are important dedicated meeting spaces to help identify gaps and implementation weaknesses related to the program and monitoring data in order to make program corrections, as well as to carry out future program planning.

4. DATA SOURCES

Multiple data sources can be used for monitoring IYCF programs depending on the purpose, focus of the system, and questions being asked. As a result, quantitative or qualitative methods might be used and information from different sources might be collected routinely on an ongoing basis, while others might be episodic or on an “as needed” basis to better understand “why” questions for process evaluation purposes. Although entirely new systems can be developed for monitoring, this can be costly and might not be needed or sustainable.

In many cases, the only data sources available are those used as part of program management and government information systems. For 2013, UNICEF (2014) reported that only 60% of countries had >1 IYCF indicator in their national information system and only 38% routinely collected monitoring data at the community level. The government information systems are sources for internal monitoring and may include data from health clinic records, such as counseling services, antenatal care visits, and other patient records, program records, growth monitoring records, supply inventory logs, and training records, for example. Benefits of these types of data sources include taking advantage of the existing infrastructure of the system, which reduces costs, and using data that are already routinely collected and reported. Some limitations of these types of systems include that they may not be representative of the population if they only collect information on participants who use these services or they may not be able or willing to collect all prioritized indicators because of the burden on those reporting and analyzing the data at government facilities. Furthermore, when integrating into weak systems that collect poor quality data, such as staff do not regularly complete paperwork and send reports, or the data are not analyzed and disseminated in a timely way, for example, might result in poor quality monitoring data if it is not possible to strengthen the system. It may be useful to examine the quality of primary care services, coverage of other interventions, and data related to supportive supervision to help assess how well the system might function for monitoring of IYCF programs.

When a partner or contractor is supporting the implementation of a government program, they sometimes bring increased human and other resources to support the program; this may result in additional or more intensive collection of qualitative and quantitative internal monitoring data. With pilot programs that have not yet been officially adopted or included in the government system, it may not be possible to include any indicators in the government information systems for the area covered by the pilot. In this case, entirely new parallel monitoring systems may need to be developed during the pilot phase of the program lifecycle until the new program is fully adopted and integrated into government systems.

Other examples of data sources that could be used for internal or external monitoring include cross‐sectional surveys, sentinel sites, mobile phone text messages (short message service [SMS]), and media assessment audits. Cross‐sectional surveys can be designed to collect information from program participants; the target population of the program; health care providers, program delivery staff, community workers, and volunteers involved in IYCF program delivery; or community leaders, for example. Cross‐sectional household surveys that are regularly collected for another purpose, such as the Demographic Health Surveys, Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys, or other program‐specific surveys, may also include complementary feeding indicators even if they are not the main focus of the survey. Note that it is important to review the “standard” complementary feeding indicators included in Demographic Health Surveys and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys type surveys, because they may only include the international IYCF caregiver report of feeding practice indicators (WHO, 2008) and no other relevant IYCF program indicators, such as caregiver report of receipt of complementary feeding counseling or messages, which may also be necessary. Sentinel sites are designated areas, such as communities, hospitals, health clinics, or schools, for example, that are strategically selected for routine or periodic data collection with the target population, and multiple types of data can be collected at the site. Systems that use mobile phone SMS technology can be used for various monitoring purposes, such as tracking supply, stock outs, or service provision, for example. Once the technology infrastructure is established, it can potentially be used by multiple programs regardless of the target population or program delivery platform. In areas where mobile phone ownership is high, and especially when these systems are already established in the program area, they can serve as potentially useful data sources (e.g., community volunteers send an SMS each time they deliver counseling or messages indicating the content of the counseling/message, such as initiation of complementary foods at 6 months of age). Media assessment audits track the media “hits” and exposure to the media messages and also examine the content sent through the media channels. If the evidence base for delivery of IYCF messages to change behavior of caregivers continues to grow (e.g., Monterrosa et al., 2013), message delivery through media might begin to have a more prominent role in government programs. When media plays a strong role in a complementary feeding program, media audit assessments can be important means to verify that the intended audiences are being reached as planned.

5. ROUTINE INDICATORS FOR COMPLEMENTARY FEEDING IN GOVERNMENT SYSTEMS

Indicators measure whether specific actions, activities, outputs, or outcomes have been achieved. IYCF programs and indicators in government systems vary across countries, but most IYCF indicators routinely collected through government HMIS are focused on the health service‐level and community‐level actions due to the nature and location of these activities (see Table 1 for examples of indicator titles in government information systems). IYCF indicators typically focus on maternal/caregiver receipt of nutrition counseling (maternal nutrition, breastfeeding, and complementary feeding) carried out by health staff, community workers, or volunteers. This individual or group counseling may occur during pregnancy, immediately after birth, and thereafter periodically until the child is 23 months of age. Indicators may also monitor reported feeding practice, such as exclusive breastfeeding or age of introduction of complementary foods. Where there are home fortification with micronutrient powder programs in place, there might also be indicators related to micronutrient powder counseling or coverage.

Table 1.

Examples of indicator titles for infant and young child feeding programs in government information systems

| Indicator titlea | Possible source/health facility register |

|---|---|

| Counseling | |

| Breastfeeding and complementary feeding | Antenatal register |

| Feeding at discharge (exclusive breastfeeding, replacement feeding, mixed feeding) | Maternity register |

| Postnatal register | |

| Infant feeding | Antenatal register |

| Postnatal register | |

| Infant and young child feeding | Child register |

| Initiation of complementary feeding and continued breastfeeding | Child register |

| MNP | Child register |

| Practices | |

| Initiation of breastfeeding ≤1 hr | Maternity register |

| Exclusive breastfeeding | Postnatal register |

| Child register | |

| Initiation of complementary feeding at 6 months | Child register |

| Minimum dietary diversity and complementary feeding | Child register |

| MNP distribution | Child register |

| Received MNP sachets | Child register |

| Received first batch MNP sachetsb | Child register |

Republic of Uganda, Ministry of Health, 2014; Bangladesh, Directorate General of Family Planning http://dgfpmis.org/pusti/dashboard/dash_board.php accessed 14 October 2016; Personal communication, Mr. Pradiumna Dahal, UNICEF Nepal.

Similar titles for second and third subsequent batches of micronutrient powder (MNP) sachets.

Identifying complementary feeding indicators contextualized to the government program, capacity, and setting that are useful for decision‐making and program improvement is a key step toward strengthening complementary feeding programs. As a main component of IYCF programs, indicators documenting counseling (receipt of, and ideally also, quality of that counseling) are often prioritized in many countries. However, indicators that monitor initial and ongoing training of staff and volunteers, capacity building, and supportive supervision are also required to strengthen weak IYCF programs and may not currently be in place. In some cases, IYCF counseling is separated out into specific indicators, particularly for breastfeeding (e.g., counseling on early initiation of breastfeeding within 1 hr of birth or exclusive breastfeeding), but typically there are fewer complementary feeding indicators, and it is not uncommon to see only a comprehensive “IYCF counseling” indicator. Where this is not already occurring, it may be useful to consider reporting counseling (or message delivery) on complementary feeding separately from a more comprehensive indicator of receipt of “nutrition counseling” or “IYCF counseling,” assuming counseling on complementary feeding is being implemented in the IYCF program package. Furthermore, distinguishing receipt of group counseling as opposed to individual counseling may be useful because the nature of individual counseling is different and would likely be more tailored and specific to the child. As complementary feeding guidance changes as the child increases in age (UNICEF, 2011), documenting that the mother/caregiver received counseling at key ages to match program guidance (e.g., counseling on initiation of complementary feeding at 6 months in addition to continued breastfeeding), may also be useful as receiving complementary feeding counseling once (or not at key ages) over the 0–23 month age span of the child may not be sufficient to support optimal feeding practices. For example, in some settings, there is mostly opportunistic group counseling while waiting at health facilities for services or during periodic group meetings in communities. Including indicators of the quality of counseling, such as use of teaching aids, may also strengthen program implementation.

6. CONCLUSIONS

Protecting, promoting, and supporting appropriate IYCF practices is a global priority (WHO and UNICEF, 2003), and there is recent increased interest in accelerating progress to improve complementary feeding of young children (UNICEF and Government of Maharashtra, 2016). Improving IYCF monitoring in government information systems is an essential component of increasing country implementation strength of an IYCF program. Tools and frameworks exist to guide the development of monitoring systems and indicators for IYCF programs, and when applied can result in IYCF monitoring systems that are feasible, used to improve programs, and sustainable over the program lifecycle.

SOURCE OF FUNDING

None.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

CONTRIBUTIONS

MEJ wrote the commentary based on a presentation given at the First Foods: A global meeting to accelerate progress on complementary feeding in young children November 17‐19, 2015, Mumbai, India. MEJ gave final approval and is responsible for the content.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This proceedings paper is based on a presentation given at “First Foods: A global meeting to accelerate progress on complementary feeding in young children November 17‐19 2015, Mumbai, India.” I thank France Bégin, Laurence Grummer‐Strawn, and Edward Frongillo for suggestions when preparing the presentation.

Jefferds MED. Government information systems to monitor complementary feeding programs for young children. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13(S2):e12413 10.1111/mcn.12413

REFERENCES

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . (1999) Framework for program evaluation in public health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed 3April 2016 at http://www.cdc.gov/eval/framework/index.htm

- Habicht, J. P. , & Pelto, G. H. (2014). From biological to program efficacy: Promoting dialogue among the research, policy, and program communities. Advances in Nutrition, 5, 27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Home Fortification Technical Advisory Group (HF‐TAG) . (2013). A manual for developing and implementing monitoring systems for home fortification interventions. Geneva: HF‐TAG. Accessed 3April 2016 at http://www.hftag.org/resource/hf-tag-monitoring-manual-14-aug-2013-pdf/

- Lutter, C. K. , Iannotti, L. , Creed‐Kanashiro, H. , Guyon, A. , Daelmans, B. , Rober, R. , & Haider, R. (2013). Key principles to improve programmes and interventions in complementary feeding. Matern Child Nutr, 9(Suppl. 2), 101–115. 10.1111/mcn.12087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monterrosa, E. , Frongillo, E. , Gonzalez de Cossio, T. , Bonvecchio, A. , Villanueva, M. A. , Thrasher, J. F. , & Rivera, J. A. (2013). Scripted messages delivered by nurses and radio changed beliefs, attitudes, intentions and feeding behaviors regarding infant and young child feeding in Mexico. Journal of Nutrition, 143, 915–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Population Services International (PSI) (2000). PSI Logframe Handbook: The logical framework approach to social marketing project design and management. Washington DC: PSI. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Uganda, Ministry of Health . (2014). The health management information system, health unit and community procedure manual, volume 1. Kampala: Ministry of Health Resource Centre. Accessed 3 April 2016 at http://library.health.go.ug/publications/health-information-systems/hmis/health-management-information-system-volume-1-health

- UNICEF . (2011). Programming guide: Infant and young child feeding. New York: UNICEF. Accessed 3April 2016 at http://www.unicef.org/nutrition/files/Final_IYCF_programming_guide_2011.pdf

- UNICEF (2014). Nutridash 2013: Global report on the pilot year. New York: UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF and Government of Maharashtra . (2016). First foods: A global meeting to accelerate progress on complementary feeding in young children November 17–19 2015, Mumbai, India. Summary of global presentations and recommendations. New York: UNICEF. Accessed 3April 2016 at http://www.firstfoodsforlife.org

- WHO . (2008). Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: Conclusions of a concensus meeting held 6–8 November 2007 in Washington D.C., USA. World Health Organization: Geneva.

- WHO and UNICEF . (2003). Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. Geneva: WHO. Accessed 3April 2016 at www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/9241562218/en