Abstract

PURPOSE:

Awareness of symptoms and signs of possible complications after corneal transplantation is very important. Early presentation can enhance long-term survival of the cornea. This study evaluates the reasons for emergency presentation and management of postcorneal transplantation complications.

PATIENTS AND METHODS:

This retrospective study included a total of 134 postkeratoplasty patients at the cornea unit in Yemen Magrabi Eye Hospital in Sana’a between 2008 and 2010.

RESULTS:

The most common indication for keratoplasty was keratoconus in 103 patients (76.9%) followed by bullous keratopathy (4.5%) and corneal dystrophy (4.5%). 80 (59.7%) patients presented for emergency visits. Pain and foreign body sensation were the main presenting symptoms. Loose irritating sutures (29.9%) and graft rejection (10.4%) were the most common diagnoses. Twelve patients (8.9%) were admitted to the hospital for re-suturing.

CONCLUSION:

Proper postoperative care is critical for a successful keratoplasty; early intervention of sight-threatening complications increases the chance of graft survival and best-obtained vision. In our corneal transplantation service, all patients are routinely instructed to arrange a same day emergency visit if they experience any symptom in eyes that have undergone keratoplasty.

Keywords: Emergency visit, graft rejection, penetrating keratoplasty

Introduction

Blindness and visual impairment due to corneal diseases are a significant public health problem worldwide and in Yemen.[1,2] Corneal grafting is the most common and successful human tissue transplantation procedure.[3] Corneal graft outcome generally is measured in terms of graft survival and final visual acuity.[4,5] In Yemen, there is no eye bank and corneal tissue used for corneal transplantation is imported from Tissue Bank International (TBI, USA) and Iran Eye Bank (Tehran, Iran).

Preoperative counseling for corneal transplantation should include awareness of symptoms and signs of possible complications as early presentation can enhance long-term success.[6] The outcome following successful corneal transplantation not only depends on the underlying diagnosis and surgical technique but also on careful postoperative management and patient compliance with treatment.[7] The chance of graft survival and improvement of vision are in part attributed to improved surgical technique, better donor tissue management, early recognition, and prompt intervention of postoperative sight-threatening complications.[4]

All patients who have penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) or deep lamellar keratoplasty are routinely instructed to arrange a same-day emergency visit if they experience any symptom in eyes which have undergone keratoplasty. All patients are given instructions that all visits during the 1st year after the PKP are free. This encourages majority of patients if they have a problem not to worry regarding expenses of visiting the clinic or the emergency department. Hospitals performing corneal transplantation usually have appropriate backup facilities for assessing their patients who present with acute problems. Recognizing potential complications and seeking treatment immediately usually improve graft survival.[6]

This study evaluates the different complaints and reasons for presentation as emergency visits after corneal graft. It shows that a simple open access system facilitates early presentation and successful management of postgraft complications.

Patients and Methods

This retrospective study included a total of 134 postkeratoplasty patients at the cornea unit in Yemen Magrabi Eye Hospital (YMEH) in Sana’a. The corneal transplantations were done between 2008 and 2010 and the follow-up visits extended till end of 2012. Eighty (59.7%) patients attended for emergency visits between January 2008 and December 2012.

Patients who had corneal transplantation and presented as emergency visits and who were operated at YMEH, during the 3 years (January 2008 and December 2010) were all included in the study. Patients who presented as emergency visit postcorneal transplantation and who underwent the surgery before or after the study period or have the surgery done in other hospitals were excluded from the study.

As per YMEH protocol, all of these surgeries were performed by three expert surgeons using well-adjusted buried-interrupted or combined-interrupted and continuous sutures. Patients were followed up for a minimum of 1 year, and the follow-up protocol normally included twelve scheduled examinations in the 1st year, four examinations in the 2nd year, and six monthly, thereafter. All patients were instructed to visit the hospital, day or night, even during weekend as soon as they experience any unusual complaint without prior appointment (open and free access system). These patients were educated and informed on different symptoms they might experience, such as red eye, pain or gritty sensation, discharge, tearing, photophobia, and sudden blurring of vision. Patients were also educated on graft rejection and the risk of late presentation.

These patients are evaluated on the same day by the resident on call and prompt treatment is commenced as necessary as early as possible. The resident usually retrieves preoperative information from the patient's medical record. In each visit, the patient is assessed regarding symptoms, signs, best-corrected vision (BCVA), slit lamp examination, and intraocular pressure measurement.

Data collected included time from surgery, reason for presentation, duration of symptoms, and number of emergency visits by a single patient, clinical management, and outcome of each emergency visit. Descriptive analysis was performed on the data collected using Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Seattle, USA).

The study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of YMEH, and the procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional or regional), and with the Declaration of Helsinki, 1975 as revised in 2000. The risk of the surgery was fully explained to the patients in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and verbal informed consent was obtained.

Results

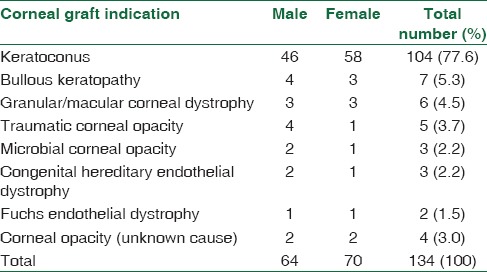

One hundred and thirty-four patients were included in the study. Mean age was 23.21 + 11.48 (range 7–65). There were 64 (47.8%) males and 70 (52.2%) females. The most common indication for keratoplasty was keratoconus in 104 patients (77.6%) followed by bullous keratopathy in 7 patients (5.3%) and corneal dystrophy in 6 patients (4.5%) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Preoperative diagnoses of 134 eyes undergoing corneal grafts

Eighty patients (59.7%) with varied preoperative diagnoses presented for emergency visits after their corneal transplantation. 47 patients visited the Emergency Department within the 1st month after surgery and 23 patient visited within the first 3 months and 10 patients within the 1st year. 54 patients sought consultation more than twice during the study period and 21 patients presenting more than 3 times.

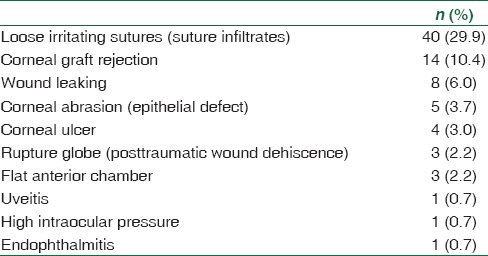

Loose irritating corneal sutures were seen in 40 patients (29.9%) and graft rejection in 14 patients (10.4%) and both causes were the two most common diagnoses for presentation as emergency after PKP. Wound leaking was the presenting diagnosis in 8 cases (6.0%) and posttraumatic wound dehiscence in 3 patients (2.2%).

Twelve patients (8.9%) were admitted to the hospital for re-suturing. Admission for re-suturing due to wound dehiscence was seen in eight patients, ruptured globe posttraumatic was seen in three patients and one patient with flat anterior chamber which needed reformation of the anterior chamber and re-suturing. The three patients who presented after trauma complained of painful loss of vision, broken sutures, and leaking corneal wound. All were admitted and surgically repaired.

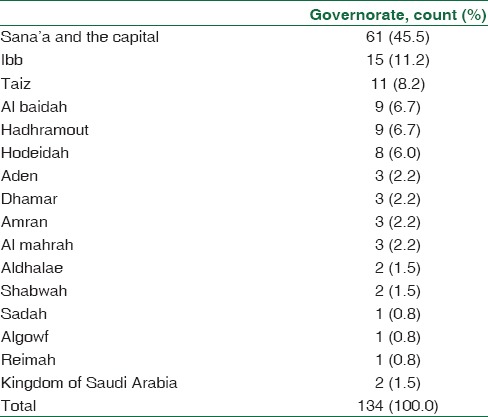

One patient was admitted with endophthalmitis and was treated with daily vigorous topical fortified eye drops, but it did not respond to treatment and ended with evisceration. Other presenting diagnoses are listed in Table 2. Table 3 shows the governorate that the patient is resident after the corneal graft.

Table 2.

Diagnosis made on presentation at emergency visits (n=134 patient)

Table 3.

Governorates that patient belong to (n=134)

Discussion

Corneal grafts are successful particularly for keratoconus.[8] Close follow-up is important for graft survival and visual outcome. Early intervention of sight-threatening complications, proper diagnosis, and proper management of complications in the early stages increases the chance of graft survival, prevents graft failure, and improves long-term graft survival and best-obtained vision. Centers performing corneal graft surgery should have the appropriate backup facilities for assessment of patients who present with acute problems.[6,7]

The improvement in surgical techniques and tissue banking and corneal preservation have resulted in better results and less incidence of postoperative complication of PKP.[9]

Patients are educated to seek immediate treatment for symptoms such as redness, pain, decreased vision, sensitivity to light, or any other symptoms in eyes that have undergone keratoplasty. Prevention of suture-related complications requires frequent monitoring and timely intervention,[10] but graft rejection remains the most common cause of corneal graft failure.[8,11]

The outcome following successful corneal transplantation not only depends on the underlying diagnosis and surgical technique but also on careful postoperative management and patient compliance with treatment. Early intervention of sight-threatening complications increases the chance of graft survival and best-obtained vision. This study shows a simple open access system that facilitates early presentation and successful management of postgraft complications. Postoperative treatment normally included prednisolone acetate 1% (Pred Forte, Allergan, USA), ciprofloxacin 0.3% (Ciloxan, Alcon, USA), and xolamol (Jamjoom Pharma, KSA) eye drops. Sutures are normally removed after 12 months unless they were loose, causing irritation or severe astigmatism by topography they are removed earlier.

In a previous study done in Yemen, for corneal grafts which were done abroad the main indications were keratoconus (48.6%), traumatic corneal opacity (17.2%), and microbial corneal opacity (11.4%).[5] 18.6% of corneas became opaque and the most common graft-related complications were suture-related problems.[5] In this study, keratoconus remained the main indication of corneal graft followed by bullous keratopathy and traumatic corneal opacity.

The main diagnosis for emergency visits was loose irritating sutures and suture infiltrates (29.9%). Corneal graft rejection (10.4%) was the second main presenting diagnosis. Wound leaking, dehiscence of wound due to ruptured globe, and flat anterior chamber accounted for 6.0%, 2.2%, and 2.2%, respectively. The corneal graft creates a permanent weakness in the eyeball making it amenable to a lifelong risk of wound-related problems.[12]

Most loose sutures were removed within 1 or 2 weeks of presentation depending on the reaction and infiltration associated with the loose suture. Pain, blurred vision, sensitivity to light, and foreign body sensation were the main presenting symptoms for suture-related problems. Immediate removal of loose or broken sutures is essential to avoid sight-threatening complications such as graft rejection and/or infection.[6] The suture erosions occur at any time after surgery ranging from weeks to months and sometime years. Majority of cases were done by combined interrupted and continuous sutures, and it was very difficult to find out if interrupted sutures alone or continuous sutures alone had a higher suture-related problem.

Rejected grafts were treated as outpatient cases and followed daily. These patients were treated with intensive topical steroids (1% prednisolone) and systemic steroids. Blurring of vision was the most common symptom for emergency visits in patients with graft rejection. Fourteen patients in our study that presented with signs of rejection and because of early presentation and the open access system, eleven of them had graft survival, and this is comparable with other studies.[6,7]

Graft dehiscence can occur for a variety of reasons after PKP, including trauma, infectious keratitis, suture failure, or spontaneous wound separation. The graft-host interface remains vulnerable after corneal transplant and is a potential area for wound dehiscence even many years after keratoplasty.[13] Re-suturing may have to be performed more commonly for corneal transplantation surgery done for microbial keratitis and keratoconus.[12] The major indications for re-suturing are wound dehiscence and loose/broken sutures. In our study, 12 patients (8.9%) were readmitted and their corneal graft resutured and this is higher compared to other studies were the incidence of re-suturing was 5.4%.[12]

Infectious keratitis was seen in two patients and one patient presented with endophthalmitis. Infectious keratitis post-PKP in Saudi Arabia was in 4.8%,[13] in Jordan in 10%,[7] and in the USA in 1.8%.[14]

More than half of the patients (54.5%) are resident in governorates far from the capital Sana’a [Table 3]. This makes the follow-up for patients’ that had keratoplasty sometimes difficult as they have to travel to the hospital from distances that might take days to see the operating doctor. Because of the free and open-access system, majority of patients present to the emergency department whenever they have symptoms or signs that makes them worry.

One limitation to our study was that it did not look for the hygiene and income of this group of patients as some of these patients has poor income and poor hygiene which might affect negatively to the result of the corneal graft. Another limitation of this study was that no comments were put in the case notes related to dry eyes or ocular surface problems but most of patients were using tears substitute drops postoperatively.

One might think that some patients might misuse the open access system, but from this study, almost all emergency visits were highly relevant. Establishing an eye bank in Yemen is important to reduce the magnitude of corneal blindness parallel to changing the cultural attitudes to corneal donations.

Conclusion

In our corneal transplantation service, all patients are routinely instructed to arrange a same-day emergency visit and seek prompt treatment for symptoms if they experience any unusual symptom in eyes which have undergone keratoplasty. Proper postoperative care is critical for a successful PKP and early intervention of sight-threatening complications increases the chance of graft survival, graft clarity, and final visual acuity.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank administrators and staff of YMEH for permitting us to conduct this study. They assisted and contributed in the patient's care in our study. Finally, we appreciate the efforts and cooperation of all patients they extended to us in this study.

References

- 1.Al-Akily S, Bamashmus M. Causes of blindness in adult Yemeni patients-hospital-based study. Middle East J Ophthalmol. 2008;15:3–6. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.53367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Z, Cui H, Zhang L, Liu P, Bai J. Prevalence of and associated factors for corneal blindness in a rural adult population (the Southern Harbin eye study) Curr Eye Res. 2009;34:646–51. doi: 10.1080/02713680903007139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tham VM, Abbott RL. Corneal graft rejection: Recent updates. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2002;42:105–13. doi: 10.1097/00004397-200201000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borderie VM, Boëlle PY, Touzeau O, Allouch C, Boutboul S, Laroche L. Predicted long-term outcome of corneal transplantation. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2354–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Akily S, Bamashmus M, Khalifa O. Graft survival and visual outcome of 70 corneal grafts in Yemeni patients. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2005;19:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gnanaraj L, Sandhu S, Hildreth AJ, Figueiredo FC. Postkeratoplasty emergency visits – A review of 100 consecutive visits. Eye (Lond) 2007;21:1028–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asfour WM, Shaban RI. Post-keratoplasty emergency visits at a hospital in Jordan. Saudi Med J. 2009;30:1568–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Javadi MA, Motlagh BF, Jafarinasab MR, Rabbanikhah Z, Anissian A, Souri H, et al. Outcomes of penetrating keratoplasty in keratoconus. Cornea. 2005;24:941–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000159730.45177.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehlers N, Hjortdal J, Nielsen K. Corneal grafting and banking. Dev Ophthalmol. 2009;43:1–14. doi: 10.1159/000223833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vajpayee RB, Sharma N, Sinha R, Agarwal T, Singhvi A. Infectious keratitis following keratoplasty. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Omar N, Bou Chacra CT, Tabbara KF. Outcome of corneal transplantation in a private institution in Saudi Arabia. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:1311–8. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S43719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeganathan SV, Ghosh S, Jhanji V, Lamoureux E, Taylor HR, Vajpayee RB. Resuturing following penetrating keratoplasty: A retrospective analysis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:893–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.133421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Renucci AM, Marangon FB, Culbertson WW. Wound dehiscence after penetrating keratoplasty: Clinical characteristics of 51 cases treated at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute. Cornea. 2006;25:524–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000214232.66979.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagoner MD, Al-Swailem SA, Sutphin JE, Zimmerman MB. Bacterial keratitis after penetrating keratoplasty: Incidence, microbiological profile, graft survival, and visual outcome. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1073–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]