Abstract

Background

Weight regain (WR) and symptoms of post-bariatric surgery hypoglycemia (PBSH) are metabolic complications observed in a subset of post-bariatric patients. Whether hypoglycemic symptoms are an important driver of increased caloric intake and WR after bariatric surgery is unknown.

Objective

This study aims to determine whether patients with PBSH symptoms have greater odds for WR.

Setting

Tertiary Academic Hospital

Methods

Patients who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) or sleeve gastrectomy (SG) at our tertiary academic hospital from Aug 2008-Aug 2012 were mailed a survey, from which weight trajectory and PBSH symptoms were assessed. Percent WR was calculated as 100x(current weight-nadir weight)/(preop weight-nadir weight) and was compared between dates of survey completion and bariatric surgery. The primary outcome was WR≥10%, as reflection of the median WR among respondents. Multivariable logistic regression was used to determine clinical factors that indicate greater odds for WR≥10% at the p<0.05 level.

Results

Of 1119 potential patients, there were 428 respondents (40.6%) eligible for analysis. WR was observed in 79.2% (N=339), while 20.8% (N=89) experienced either weight loss or no weight regain, at a mean of 40.6 ± 14.5 months. Median WR was 10.8% [interquartile range (IQR)5.6,19.4]. Odds of WR≥10% was significantly increased in those who experienced PBSH symptoms (OR=1.66; 95%CI:1.04–2.65), reported less adherence to nutritional guideline (OR= 2.36; 95%CI=1.52–3.67), and had longer time since surgery (OR=1.05; 95%CI:1.03–1.07).

Conclusions

We found evidence that the presence of PBSH symptoms was associated with WR. Future studies should elucidate the role of hypoglycemia among other factors in post-bariatric surgery WR.

Keywords: weight regain, bariatric surgery, glucose metabolism, treatment outcomes, post-bariatric hypoglycemia

Introduction

Bariatric surgery is a highly effective treatment for patients with severe obesity and obesity-related co-morbidities, such as diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia1. However, the amount of weight loss and its successful maintenance varies for individual patients. While most patients achieve maximum weight loss within the first postoperative year, defined as at least 50% of preoperative excess body weight, many regain a proportion of their weight in subsequent years(2,3,4,5). Indeed, bariatric surgery proves to be effective for weight loss in the short-term(1,2,4), yet the long-term efficacy of postsurgical weight maintenance and the driving factors for weight regain (WR) are less clear.

In addition to promoting weight loss, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and sleeve gastrectomy (SG) affect glucose homeostasis in a rapid and durable manner (6). Post-bariatric surgery hypoglycemia (PBSH) is an increasingly recognized complication associated with the inappropriate secretion of insulin and gastrointestinal hormones(7,8,9). PBSH is also known as late dumping syndrome, an entity that differs from early dumping syndrome in its delayed onset of 1–2 hours after a meal without vasomotor symptoms(27). While most cases are self-limited, some patients experience severe and potentially life-threatening hypoglycemia, associated with seizures, loss of consciousness, and motor vehicle accidents(8). Although the prevalence of PBSH is thought to be low, we have previously reported that up to a third of patients who have undergone RYGB or SG report symptoms of PBSH(10).

While both RYGB and SG bring changes in glucose metabolism, the mechanism through which they achieve these changes are thought to be different. Hypoglycemia after RYGB is thought be mediated partly by expedited gastric emptying as well as by an increase in glucose-mediated GLP-1 secretion and subsequent insulin secretion(24,25). The mechanism behind hypoglycemia after SG is unknown. Regarding the prevalence of hypoglycemia after each procedure, we have previously reported that undergoing RYGB was associated with risk for symptoms of PBSH, whereas no association was seen after SG (10). However, the lack of evidence for PBSH after SG may be due to the fact that the procedure is newer, with less longitudinal outcome data.

Other clinical factors reported to be associated with WR after bariatric surgery include low physical activity, poor dietary adherence, psychosocial stress, and low energy metabolism(3,11). To our knowledge, whether the presence of PBSH contributes to WR has not yet been explored; however, several studies have reported that patients with hypoglycemia also present with weight gain(12,13,14,15). The risk for weight gain in diabetic patients, who experience hypoglycemia while receiving insulin therapy is common(1,13). Similarly, weight gain is a known complication in patients with insulinoma, due to increased frequency and amount of food eaten in order to avoid or prevent hypoglycemia, in combination with insulin’s anabolic effects(14). Finally, there is preclinical evidence to support that insulin-induced hypoglycemia stimulates peripheral and central nervous system responses that lead to increased hunger, food intake and weight gain(15,16).

The plausible link between hypoglycemia and weight gain, in addition to the fact that weight regain and hypoglycemia are recognized metabolic complications after bariatric surgery, led to the hypothesis that post-bariatric hypoglycemia may be an important contributor to weight regain. Thus, this study sought to determine whether patients with post-bariatric hypoglycemic symptoms demonstrate greater odds for weight regain after bariatric surgery.

Methods

As previously described, we collected survey data from the patients who underwent bariatric surgery at our institution (10).

Participants

Patients who underwent either RYGB or SG between August 2008 and August 2012 at our tertiary academic center were identified. We collected data by mailing a questionnaire to 1119 patients regarding hypoglycemic symptoms, demographics, and weight data between August 2013 and April 2014. Multiple attempts were made to follow up with each subject using two additional questionnaire mailings and two reminder postcards. The Institutional Review Board of the tertiary academic center exempted the study from further review. Consent was assumed by completion of the questionnaire(10).

Hypoglycemia Questionnaire

We used modified questions from the Edinburgh Hypoglycemia questionnaire to assess hypoglycemic symptoms in this study’s post-bariatric patients(10,17). The 11 key hypoglycemic symptoms comprised in the questionnaire include sweating, palpitation, shaking, hunger, confusion, drowsiness, odd behavior, speech difficulty, incoordination, nausea, and headache(17).

As reported previously, we dichotomized patients into either a low or high suspicion group for PBSH based on the number of symptoms, or a self-report of diagnosed, severe hypoglycemia(10). The low suspicion group was defined as those who experienced at most two of the 11 key validated hypoglycemic symptoms(10); the high suspicion group was defined as those who experienced at least three hypoglycemic symptoms and/or a history of requiring assistance, seizure, or medical diagnosis of hypoglycemia(10).

Weight and Additional Data

“The questionnaire additionally collected pertinent clinical and surgical data. Age (at time of surgery), gender, race, bariatric procedure (RYGB or SG) and date were cross-confirmed by using our tertiary center’s electronic medical record system. Participants were also asked to report immediate pre-operative, nadir, and current weights – all of which represent self-report values. Percentage WR, based on self-report, was expressed as 100x(current weight–nadir weight)/(preoperative weight–nadir weight). We generalized that nadir weight was achieved at 12 months post-surgery due to several bariatric reports showing that the time of maximal weight loss, while unique for each individual patient, largely falls in near the time of the first and second postoperative years(1,2,4,5,21). The primary outcome was defined as WR≥10% (reflecting the median percentage WR of respondents) of maximum weight loss following RYGB or SG. We assessed nutritional adherence by asking “How often are you following the diet plan given to you by the dietician/nutritionist?”. We then dichotomized patients based on the following 5-point Likert-scale responses: high adherence (“Always”, or “Very Often”) or low adherence (“Sometimes”, “Rarely”, or “Never”).”

Statistical Analysis

We utilized chi-squared, independent sample T-tests, and univariate logistic regression to examine the clinical variables in relation to WR≥10% (the primary outcome variable). Multivariable logistic regression determined the factors independently associated with WR≥10%. All variables were examined at the p<0.05 level of significance. Variables statistically significant at the p<0.05 level in univariate analyses and those deemed clinically important in contributing to WR were included in the final logistic regression model (age, race, gender, time since surgery, bariatric procedure type, history of diabetes, adherence to nutritional guidance, total body weight loss percentage).

Furthermore, we performed several stratified analyses in order to understand the effect of potential confounders on WR, including time since surgery, procedure type, and nutritional adherence. Because of the differential length of follow up across participants, we stratified respondents into 3 groups (0–24, 24–48, >48 months since surgery) and performed ANOVA and separate multivariable regressions to better understand the role of time since surgery and PBSH symptoms on WR≥10%. To examine any differences of RYGB or SG on WR and PBSH symptoms, we stratified the patients by surgery type and performed multivariate regression analysis within each group separately. Given the concern that the presence of PBSH symptoms may be a surrogate marker of poor dietary adherence, we also performed a stratified analysis by each level of nutritional adherence. All analyses were performed using STATA version 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Of 1119 potential patients, 55 did not have valid addresses and were excluded from the study. Four-hundred-fifty-four (40.6%) individuals responded to the request to complete the questionnaire (hereto referred to as “respondents”). Respondents who did not report current weight, nadir weight, or preoperative weight (N=7), nutritional guideline adherence (N=6), height (N=1), or hypoglycemic symptoms (N=1) or who had a calculated preoperative Body Mass Index (BMI) below 33 kg/m2(N=11) were excluded. The latter were excluded due to concern for error in reported data. Twenty-six respondents were excluded from analysis, yielding 428 eligible respondents (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of All Respondents and Respondents Stratified by Weight Regain

| All (N=428) | Those with Weight Regain≥10% (N=180) | Those with Weight Regain<10% (N=248) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 50.4 ± 11.2 | 51.6 ± 11.0 | 49.5 ± 11.2 | 0.049 |

| Time since Surgery (Months) | 40.6 ± 14.5 | 34.4 ± 12.6 | 24.3 ± 14.3 | <0.001 |

| Gender | 0.514 | |||

| Male | 91 (21.3%) | 41 (22.8%) | 50 (20.2%) | |

| Female | 337 (78.7%) | 139 (77.2%) | 198 (79.8%) | |

| Race | 0.646 | |||

| Non-Caucasian | 121 (28.3%) | 53 (29.4%) | 68 (27.4%) | |

| Caucasian | 307 (71.7%) | 127 (70.6%) | 180 (72.6%) | |

| Surgery | 0.075 | |||

| VSG | 94 (22.0%) | 32 (17.8%) | 62 (25.0%) | |

| RYGB | 334 (78.0%) | 148 (82.2%) | 185 (75.0%) | |

| History of Diabetes | 0.777 | |||

| No | 272 (63.6%) | 113 (62.8%) | 159 (64.1%) | |

| Yes | 156 (36.5%) | 67 (37.2%) | 89 (35.9%) | |

| Adherence to Nutritional Guidelines | <0.001 | |||

| Low Adherence | 246 (57.5%) | 130 (72.2%) | 116 (46.8%) | |

| High Adherence | 182 (42.5%) | 50 (27.8%) | 132 (53.2%) | |

| Postoperative Hypoglycemic Symptoms | 0.013 | |||

| Low Suspicion | 283 (66.1%) | 107 (59.4%) | 176 (71.0%) | |

| High Suspicion | 145 (33.9%) | 73 (40.6%) | 72 (29.0%) | |

| Preoperative BMI (kg/m2) | 49.7 ± 12.0 | 48.7 ± 11.2 | 50.4 ± 12.5 | 0.149 |

| Change in BMI (kg/m2) | 18.4 ± 7.1 | 17.8 ± 6.7 | 18.9 ± 7.3 | 0.348 |

| Maximum Total Body Weight Loss (%) | 36.9 ± 9.9 | 36.6 ± 9.9 | 37.1 ± 9.9 | 0.146 |

| Excess Weight Loss (%) | 79.7 ± 24.0 | 81.0 ± 24.9 | 78.9 ± 23.4 | 0.374 |

Values are shown as either Mean ± Standard Deviation or N(%). WR: Weight Regain, RYGB: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, SG: sleeve gastrectomy, BMI: Body Mass Index. Change in BMI was calculated as preoperative BMI – nadir BMI. Maximum total body weight loss percentage was calculated as 100*(preoperative weight – lowest postoperative weight)/preoperative weight. Excess weight loss was calculated as (pre-operative weight – lowest postoperative weight)/(pre-operative weight – ideal weight based on goal BMI of 25 kg/m2).

Respondents were on average 50.4 ± 11.2 years old (range 21–78 years). The sample was predominantly female (78.7%) and non-Hispanic Caucasian (71.7%) who underwent RYGB (78.0%). Over a third of respondents reported experiencing PBSH symptoms (33.9%) and history of pre-existing diabetes (36.5%). Mean time since surgery, preoperative BMI, and percentage of maximum total body weight loss were 40.6 ± 14.5 months (range 1–58 months), 49.7 ± 12.0 kg/m2 (range 33.1–104.7 kg/m2), and 36.9 ± 9.9% (range 5.3–57.6%), respectively. Most respondents (79.2%) experienced any WR (WR>0%). The remaining (20.8%) experienced either weight loss or no WR. Among those with any WR, the median WR percentage from nadir was 10.8% (interquartile range 5.6%–19.7%). About one-fifth of respondents (N=83, 19.4%) regained over 20% of their maximum weight loss. Compared to the respondents who lost weight or experienced minimal WR, those with WR≥10% included significantly more patients who reported experiencing PBSH symptoms (40.6% vs 29.0%), longer time since surgery (34.4 vs 24.3 months), less adherence to postsurgical nutritional guidelines (27.8% vs 53.2%), and older age (51.6 vs 49.5 years) (Table 1).

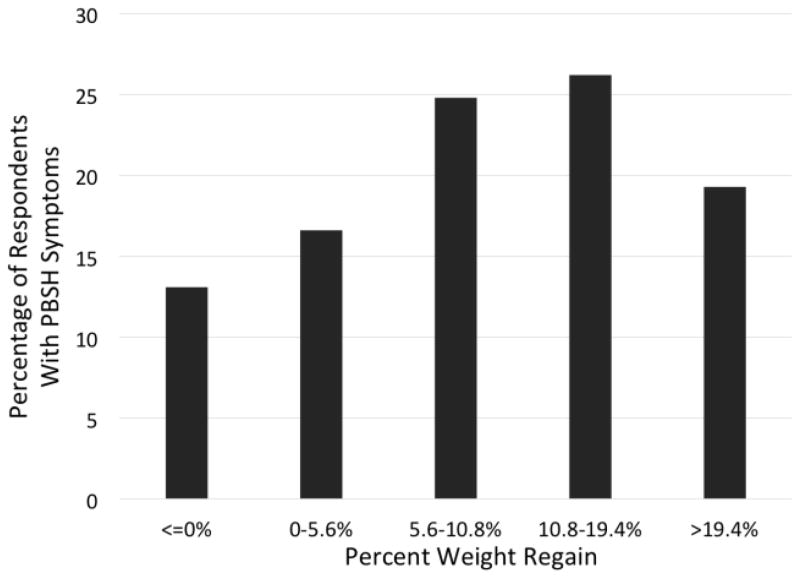

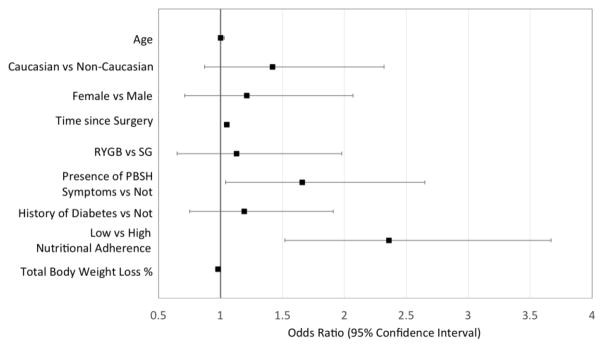

In univariate analysis, the presence of PBSH symptoms was significantly associated with WR≥10% [(Odds Ratio, 95% Confidence Interval) OR=1.67, 95%CI:1.11–2.50]. There was a clear increase in the frequency of PBSH symptoms among the WR quartiles; a definite trend indicates highest frequency of PBSH symptoms present in respondents who experienced between 5.6–10.8% and 10.8–19.4% WR, capturing 24.8% and 26.21% of the total respondent population, respectively (Figure 1). There is also a noted decrease in the frequency of PBSH symptoms in those who regain the most weight (>19.4% WR) (Figure 1). Unadjusted results showed that longer time since surgery (OR=1.05 for each additional month, 95%CI:1.04–1.07), less adherence to nutritional guidelines (OR=3.0, 95%CI: 1.96–4.46), and older age (OR=1.02, 95%CI: 1.0–1.04) were each independently associated with WR≥10%. After multivariable adjustment, only the presence of PBSH symptoms (OR=1.66; 95%CI:1.04–2.65), lower adherence to nutritional guidance (OR= 2.36; 95%CI:1.52–3.67), and longer time since surgery (OR=1.05; 95%CI: 1.03–1.07) remained significantly associated with WR of 10% or greater (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Post-bariatric Surgery Hypoglycemic Symptoms

PBSH: Post-Bariatric Surgery Hypoglycemia, Each bar reflects [number of respondents with PBSH symptoms]/[number of respondents who regained the specified amount of weight]: ≤0%WR = [19/89]; 0–5.6%WR = [24/84]; 5.6–10.8%WR = [36/86]; 10.8–19.4%WR = [38/82]; >19.4%WR = [28/87].

Figure 2.

Odds of Regaining over 10% of Maximum Weight Loss given the Potential Clinical Correlates

RYGB: Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. SG: Sleeve Gastrectomy.

Several stratified analyses were performed. Patients who were 0–24 months, 24–48, or >48 months since surgery, showed 4.4%WR, 9.2%WR, and 16.2% WR, respectively (p<0.001). Only those who were >48 months since surgery had increased odds for WR≥10% with PBSH symptoms (OR = 2.35, 95%CI: 1.04–5.32). With regard to bariatric procedure, the proportion of those who developed symptoms of PBSH was 18.0% after SG and 38.3% after RYGB. Further examination showed that those who underwent RYGB and experienced PBSH symptoms showed increased odds for WR≥10% (OR = 1.75, 95%CI: 1.04–2.92), while those who underwent SG with PBSH symptoms did not (OR = 1.35, 95%CI: 0.402–4.57). Separate stratified analysis by level of nutritional adherence showed a positive association between WR≥10%and presence of PBSH symptoms among those less adherent to nutritional guidelines (OR=1.84; 95%CI:1.01–3.36), with no association among those with high adherence (OR=1.66, 95%CI: 0.77–3.59).

Discussion

Weight regain after bariatric surgery is a widely cited observation for which prevalence and associated clinical factors are incompletely understood. The main finding of our study has important implications in post-bariatric surgery care: respondents who reported experiencing post-bariatric surgery (PBSH) symptoms showed greater odds for weight regain (WR)≥10% (reflecting the median WR percentage among respondents). Additional clinical associations with WR≥10% included longer time since surgery and lower adherence to post-surgical nutritional guideline.

Given the concern for potential confounding due to the variables time since surgery, bariatric procedure type, and nutritional adherence on WR, these relationships were further explored in separate stratified analyses. Respondents who were over 48 months out of surgery showed the greatest amount of WR, and they also demonstrated increased odds for WR with presence of PBSH symptoms. There was a greater proportion of RYGB patients who experienced symptoms of PBSH, and these patients were also at greater odds for WR≥10%. We did not find a significant association with SG patients, although this may be due to a relatively low number of patients who underwent SG, shorter duration of follow up and subsequent limited power to detect an association. Additionally, the association between PBSH symptoms and WR≥10% remained significant only among those who reported low adherence to post-bariatric dietary guideline. Together, these findings further confirmed the relationship between WR and longer time since surgery, as well as increased odds for WR with PBSH symptoms among those who underwent RYGB and those poorly adherent to nutritional guideline.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that has addressed the link between PBSH symptoms and WR among patients who underwent either RYGB or SG. While WR is commonly observed after bariatric surgery, PBSH is often hard to recognize and not systematically assessed among this patient population(10). Whether or not patients are aware of this metabolic complication, PBSH may make patients vulnerable to behavioral modifications aimed at correcting or avoiding the hypoglycemia, and potentially leading to WR(15,16). Furthermore, the physiologic mechanisms in response to hypoglycemia may contribute to WR. For example, insulin-induced hypoglycemia has been shown to enhance glucose absorption, lower metabolic rates, remove nutrients from circulation, and cause overall low fuel availability. Insulin-induced hypoglycemia is also known to stimulate appetite and subsequent caloric intake via central nervous system stimulation(13,15,16). The combination of peripheral counter-regulatory mechanisms and central nervous system responses to hypoglycemia may contribute to WR among bariatric patients(15,16,17,18,23).

Our observation that lower post-bariatric nutritional adherence is associated with WR is well-established, as adherence to recommended postoperative lifestyle and behavior changes is associated with sustained weight loss after surgery(20). In general, sustained surgical weight loss is markedly variable due to differences in patients’ dietary habits, physical activity, genetics, changing hormonal profiles and eating behavior after surgery(19,20,21,22). Patient adherence to postoperative nutritional guideline itself is dependent upon multiple factors, including variations in self-control, intention to be physically active, readiness to behavior change, prevalence of underlying anxiety and depression, and presence of any long-standing abnormal eating behaviors(22,23). Therefore, ability to adhere to dietary guidelines postoperatively is a complex issue, and the use of systematic intervention to promote behavior change in both pre- and postoperative stages may promote sustained weight loss after bariatric surgery. Our findings highlight that little postoperative nutritional adherence may lead to WR in bariatric patients regardless of the presence of PBSH symptoms.

Several limitations of this study warrant discussion. Self-reported weights were used for analysis. Though it has been reported that true and self-reported weights highly correlate, the use of self-reported weights may introduce bias, since patients may report weights lower than true weight(21). However, Courcoulas et al. has reported that bariatric patients minimally underreport weights, with the difference between self-report and clinical weight being only 0.7 kg for women and 1.0 kg for men2. Individuals were not asked to specify the time at which they achieved maximal weight loss (nadir weight). Thus, it was assumed that maximum weight loss occurred within the first postoperative year in accordance with previous reports(1,2,3,4,5). Regarding the nutritional adherence assessment, this study relied on a single question and did not obtain any details on food intake or dietary composition. Physical activity was not also not assessed(3). The absence of physical activity data, details on food intake, dietary composition, and other measures associated with post-surgical weight trajectory may raise concern for residual confounding, which would be best addressed by a prospective study. Furthermore, the response rate of 40.6% to the questionnaire raises the possibility of response bias, although the baseline characteristics of responders and non-responders in this cohort are similar, except that the respondents tended to be older and live outside Baltimore City(10). Our group has previously discussed the limitations of the retrospective questionnaire, raising the possibility that the survey underestimates the hypoglycemia prevalence due to recall bias(10). Additionally, the survey is not supported by blood glucose data or medical records to confirm the reports of hypoglycemic symptoms, and the challenge of distinguishing between early and late dumping syndrome potentially overestimates the prevalence of PBSH(10). However, we used a validated questionnaire with reports of well-validated consequences and proof of hypoglycemia, and we performed several sensitivity analyses, as previously reported, which strengthen our results(10). Moreover, large sample size and the inclusion of both RYGB and SG patients provides further strength to this study(10).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that the presence of post-bariatric surgery hypoglycemic symptoms increases the odds for weight regain after bariatric surgery. Other clinical variables associated with weight regain included longer time since surgery and lower adherence to postsurgical nutritional guideline. The effect of the presence of post-bariatric surgery hypoglycemic symptoms on weight regain appeared to differ depending on adherence to nutritional guideline; specifically, the association was shown to be stronger among those less adherent to nutritional guidelines. Our findings support the need to further confirm the role of post-bariatric surgery hypoglycemia on weight regain and whether preventing hypoglycemia would attenuate the degree of weight regain after surgery. Ultimately, a better understanding of the clinical factors that may increase the risk for weight regain after bariatric surgery may help patients achieve better long-term weight maintenance.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Shah M, Simha V, Garg A. Review: long-term impact of bariatric surgery on body weight, comorbidities, and nutritional status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(11):4223–31. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Courcoulas AP, Christian NJ, Belle SH, et al. Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Consortium. Weight change and health outcomes at 3 years after bariatric surgery among individuals with severe obesity. JAMA. 2013;310(22):2416–25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freire RH, Borges MC, Alvarez-Leite JI, et al. Food quality, physical activity, and nutritional follow-up as determinant of weight regain after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Nutrition. 2012;28(1):53–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(8):741–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bariatric Surgery versus Intensive Medical Therapy for Diabetes - 5-Year Outcomes. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, Wolski K, Aminian A, Brethauer SA, Navaneethan SD, Singh RP, Pothier CE, Nissen SE, Kashyap SR STAMPEDE Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2017 Feb 16;376(7):641–651. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterli R, Wolnerhanssen B, Peters T, et al. Improvement in glucose metabolism after bariatric surgery: comparison of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2009;250:234–41. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ae32e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patti ME, McMahon G, Mun EC, et al. Severe hypoglycaemia post-gastric bypass requiring partial pancreatectomy: evidence for inappropriate insulin secretion and pancreatic islet hyperplasia. Diabetologia. 2005;48(11):2236–40. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1933-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldfine AB, Mun EC, Devine E, et al. Patients with neuroglycopenia after gastric bypass surgery have exaggerated incretin and insulin secretory responses to a mixed meal. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4678–4685. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marsk R, Jonas E, Rasmussen F, et al. Nationwide cohort study of post-gastric bypass hypoglycaemia including 5,040 patients undergoing surgery for obesity in 1986–2006 in Sweden. Diabetologia. 2010;53(11):2307–11. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1798-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee CJ, Clark JM, Schweitzer M, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for hypoglycemic symptoms after gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015;23(5):1079–84. doi: 10.1002/oby.21042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu LK, Benotti PN, Dwyer J, et al. Nonsurgical factors that influence the outcome of bariatric surgery: a review. Psychosom Med. 1998;60(3):338–46. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199805000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(24):2545–59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hermansen K, Davies M. Does insulin detemir have a role in reducing risk of insulin-associated weight gain? Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007;9(3):209–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2006.00665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doherty GM, Doppman JL, Shawker TH, et al. Results of a prospective strategy to diagnose, localize, and resect insulinomas. Surgery. 1991;110(6):989–96. discussion 96–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willing AE, Walls EK, Koopmans HS. Insulin infusion stimulates daily food intake and body weight gain in diabetic rats. Physiol Behav. 1990;48(6):893–8. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(90)90245-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai XJ, Widdowson PS, Harrold J, et al. Hypothalamic orexin expression: modulation by blood glucose and feeding. Diabetes. 1999;48(11):2132–7. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.11.2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deary IJ, Hepburn DA, MacLeod KM, et al. Partitioning the symptoms of hypoglycaemia using multi-sample confirmatory factor analysis. Diabetologia. 1993;36(8):771–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00401150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlson MG, Campbell PJ. Intensive insulin therapy and weight gain in IDDM. Diabetes. 1993;42(12):1700–7. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.12.1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson AH, Adler S, Stevens HB, et al. What variables are associated with successful weight loss outcomes for bariatric surgery after 1 year? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(4):697–704. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peterli R, Steinert RE, Woelnerhanssen B, et al. Metabolic and hormonal changes after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy: a randomized, prospective trial. Obes Surg. 2012;22(5):740–8. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0622-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper TC, Simmons EB, Webb K, et al. Trends in Weight Regain Following Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg. 2015;25(8):1474–81. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1560-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munzberg H, Laque A, Yu S, et al. Appetite and body weight regulation after bariatric surgery. Obes Rev. 2015;16(Suppl 1):77–90. doi: 10.1111/obr.12258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergh I, Lundin Kvalem I, Risstad H, et al. Preoperative predictors of adherence to dietary and physical activity recommendations and weight loss one year after surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(4):910–8. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laferrère B, Teixeira J, McGinty J, et al. Effect of weight loss by gastric bypass surgery versus hypocaloric diet on glucose and incretin levels in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Jul;93(7):2479–85. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braghetto I, Davanzo C, Korn O, et al. Scintigraphic evaluation of gastric emptying in obese patients submitted to sleeve gastrectomy compared to normal subjects. Obes Surg. 2009;19:1515–1521. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9954-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papamargaritis D, Koukoulis G, Sioka E, et al. Dumping symptoms and incidence of hypoglycaemia after provocation test at 6 and 12 months after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2012;22:1600–1606. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0711-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tack J, Arts J, Caenepeel P, De Wulf D, Bisschops R. Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of postoperative dumping syndrome. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:583–590. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]