Abstract

In vitro-in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) analyses translating high-throughput screening (HTS) data to human relevance have been limited. This study represents the first report applying IVIVE approaches and exposure comparisons using the entirety of the Tox21 federal collaboration chemical screening data, incorporating assay response efficacy and quality of concentration-response fits, and providing quantitative anchoring to first address the likelihood of human in vivo interactions with Tox21 compounds. This likelihood was assessed using a maximum blood concentration to in vitro response ratio approach (Cmax/AC50), analogous to decision-making methods for clinical drug-drug interactions. Fraction unbound in plasma (fup) and intrinsic hepatic clearance (CLint) parameters were estimated in silico and incorporated in a 3-compartment toxicokinetic (TK) model to first predict Cmax for in vivo corroboration using therapeutic scenarios. Toward lower exposure scenarios, 36 compounds of 3,925 with curated activity in the HTS data using high quality dose-response model fits and ≥40% efficacy gave ‘possible’ human in vivo interaction likelihoods lower than median human exposures predicted in EPA’s ExpoCast program. A publicly available web application has been designed to provide all Tox21/ToxCast dose likelihood predictions. Overall, this approach provides an intuitive framework to relate in vitro toxicology data rapidly and quantitatively to exposures using either in vitro or in silico derived TK parameters, and can be thought of as an important step towards estimating plausible biological interactions in a high throughput risk assessment framework.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Likelihood of an adverse human response to environmental chemical exposure is not adequately characterized for most of the thousands of chemicals with potential human exposure due to the limitations of traditional toxicity testing methods.1 To address the needs for higher throughput approaches reflective of human molecular pathways, the Toxicology in the 21st Century(Tox21) federal collaboration was formed with an initial focus of employing in vitro high-throughput screening (HTS) assays with a 10k chemical library (e.g., environmental, pharmaceutical, consumer- and industrial-use) in >60 HTS assays (e.g., cytotoxicity, cell stress, mitochondrial, nuclear receptors).2 Of these chemicals, >1,000 have been evaluated in the EPA’s ToxCast program (>800 HTS assays) to broaden the biological coverage.3 Hazard-based chemical assessments, using HTS data, have related chemicals to biological pathways responsible for adverse in vivo effects, but have typically not incorporated concentrations or estimated required doses needed to achieve these effects.4–9 While hypothesized pathways of concern are uncovered, doses at which these effects may manifest remain generally unknown and unaddressed for Tox21 data.

Recent efforts are building quantitative approaches to translate in vitro toxicity potencies to equivalent in vivo doses using in vitro-in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) techniques.10–13 These approaches utilize pharmacokinetic equations to estimate chemical steady-state concentrations (Css) in plasma and to dosimetrically adjust in vitro HTS potencies to estimate external dose equivalents (intake rates).10–13 Additionally the High-Throughput Toxicokinetic (HTTK) open-source R-package14, 15 can quickly calculate equivalent external doses from HTS data using multiple IVIVE models, and conversely, calculate plasma concentrations given certain dosing scenarios. The current R-package utilizes in silico estimated physicochemical parameters (e.g., hydrophobicity, acid/base dissociation constants) and two widely applied in vitro measured parameters, the chemical fraction unbound in plasma (fup) and the intrinsic hepatic clearance (CLint), to predict TK, plasma concentrations and equivalent doses. While these models have made enormous strides in translating in vitro assay data to human relevance, the analyses are limited to 1)495 chemicals with human in vitro fup and CLint data, 2)a steady-state concentration vs. a dynamic peak plasma concentration (Cmax) approach, 3)HTS without consideration of assay response efficacies or quality of HTS concentration-response data, and, most importantly, 4)methods inadequately evaluating in vitro responses with respect to clinical therapeutic outcomes to estimate the likelihood of potential human interactions with Tox21 compounds.

Pharmaceutical researchers have addressed these types of challenges using predictive in vitro models to forecast chemical-induced clinical effects. For example, the FDA has provided draft guidance documents to predict drug interaction potential including the likelihood of interaction with drug metabolizing enzymes and transporters in vivo.16 The only types of “interactions” considered here are chemical-biological target interactions. This guidance describes calculating the ratio of peak plasma concentrations (Cmax) of the chemical, at the exposure level of interest, divided by observed in vitro inhibition constant (Ki) reflective of the half-maximal in vitro activity. In this approach, a Cmax/Ki ratio ≥1 (plasma concentrations equivalent or higher than in vitro half-maximal applied concentrations) indicates a ‘likely’ in vivo interaction. ‘Remote’ possibility exists if the ratio is <0.1, or ‘possible’ if 0.1≤ratio<1. In conjunction with this ratio, the guidance describes using in vitro data where efficacies are ≥40% of an established clinical effector. This intuitive approach requires evaluating the degree of inhibition/activation, grounded with established clinical effectors, to focus research in higher-likelihood chemical-biological interactions. Researchers have already extended this type of approach to high-content screening data for identification of hepatotoxic compounds17 and variability in drug efficacies among anti-cancer compounds.18 A key challenge in applying these types of approaches to environmental compounds using Tox21/ToxCast HTS data is the lack of human pharmacokinetic data (i.e., fup and CLint).

In this study, we evaluated the utility of applying a Cmax/AC50 (analogous to Cmax/Ki) framework to data-poor compounds within Tox21/ToxCast assay data using both in vitro and in silico-derived pharmacokinetic data and models to predict the likelihood of chemical-biological interactions in humans. To evaluate the input parameters, we compared predicted in silico parameters to in vitro measured, and used in silico parameters to derive Cmax values for pharmaceuticals using therapeutic dosing scenarios to compare with measured human in vivo Cmax values. As case examples, Cmax/AC50 ratios were calculated for two biological pathways with known clinical activators. Using the ratio rankings, known activators were top-ranked, thus supporting the utility of this approach. Doses to achieve or exceed a ‘likely’ (Cmax=AC50) and ‘possible’ interaction (Cmax=0.1*AC50) were calculated for each Tox21/ToxCast chemical-assay pair and compared to estimated environmental exposures.19 This method has demonstrated the use of HTS data toward estimating likelihood of human in vivo chemical-biological interactions, which can be directly compared to exposures, and thought of as an important step towards estimating plausible biological interactions in a high throughput risk assessment framework (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Fit-for-purpose Risk-Based Framework for In Vitro-In Vivo Extrapolation (IVIVE).

Both data-rich and data-poor compounds can utilize this simplistic approach with a non-commercial toxicokinetics model (HTTK) for predicting the likelihood of in vivo interaction based on in vitro and/or in silico compound-biological activity (e.g., AC50 and efficacy). Data-rich compounds with known chemical-biological activities can be directly compared to measured in vivo Cmax values or estimated values using the HTTK model, based on known external intake exposures (such as pharmaceutical dosing) and in vitro or in silico TK parameters. Data-poor compounds can be synthesized in small quantities for evaluation in high-throughput assays (e.g., Tox21/ToxCast) for chemical-biological activity. Alternatively, bioactivity may be estimated in silico if a model is available. These data can then be applied to forecast equivalent daily dose exposures in Cmax boundary limits using a steady-state HTTK model, along with in silico or in vitro TK parameters. Measured or estimated external exposures (as obtained) can be directly compared to the equivalent daily dose exposures.

METHODS

Tox21/ToxCast HTS Data

Detailed data processing workflow is shown in Figure S1.

Tox21 pipeline

Half-maximal effective concentration (AC50), efficacy values (maximum modeled response in the dose-response model), and curve class flags for the Tox21-only HTS assays were obtained using an internally-developed approach which incorporates concomitant viability and auto-fluorescence filters to minimize false positives.20, 21

ToxCast pipeline

Similarly, ToxCast-specific assay hit-calls, AC50 values, efficacies, and curve-fitting flags were obtained from the EPA’s invitrodb_v2 database(October 2015, INVITRODB_V2_LEVEL5 folder, https://www.epa.gov/chemical-research/toxicity-forecaster-toxcasttm-data). ToxCast assay data were omitted/adjusted as noted: 1)assays with >80% noise threshold or 2)background assays were omitted (i.e., “background measurement” in “intended_target_family” column from “Assay_Summary_151020.csv”); and 3)ToxCast AC50 values were adjusted to the lowest concentration tested in lieu of the extrapolated values below the lowest evaluated concentration. The respective pipelines gave a total of 142,305 active sample id-assay pairs (44,881 Tox21 and 97,424 ToxCast).

Post pipeline processing

For prioritizing the most active chemical-assay pairs, model fits of the Tox21 data were limited to “active” versus “marginally active” calls 20, 21 or had a curve class of ±(1.1, 1.2, 2.1, 2.2).22 ToxCast chemical-assay pairs were used with limited curve-fitting flags (i.e., when ‘hitc’ column=1 with no curve-fitting flags, with flag #16(“hit-call potentially confounded by overfitting”), #17(“biochemical assay with <50% efficacy”), or both flag#16 and 17. The active sample id-assay pairs were collapsed to active chemical-assay pairs by taking the pair with the minimum AC50 value, giving 65,039 active CASRN-assay pairs (15,321 Tox21 and 49,718 ToxCast) (Table S4). An efficacy filter of ≥40% maximum efficacy was finally applied to all assays, with exceptions of the assays evaluated with respect to fold-change differences (i.e., Cellumen/Apredica/Cyprotex(APR), Attagene(ATG), CellzDirect/Life Technologies/Thermo Fisher(CLD), Bioseek(BSK), Ceetox/Cyprotex(CEETOX)) where we used a 2-fold change filter. These filters resulted in 56,135 active chemical-assay pairs (4,706 unique chemicals, 838 unique assays). Additional details can be found in the Supporting Information.

High-Throughput Toxicokinetics (HTTK)

The HTTK R-package(v1.4)14, 15, 23 3-compartment and 3-compartment steady-state models were used to predict human Cmax and equivalent dose, respectively, within the R software environment (R version 3.2.3, 2015-12-10).24 Note that “equivalent dose” here was referred to “oral equivalent dose” in previous publications.10–13, 25 The models are general, chemical independent, toxicokinetic models driven by differential equations describing the changes in chemical concentration over time, except in the steady-state model. The 3-compartment model comprises of a gut, liver, and a rest of body component that have separate tissue and blood compartments, where tissue partitioning is calculated with Schmitt’s method26, 27 using chemical-specific parameters such as the octanol:water partition coefficient, acid dissociation constant, and fup. Briefly, this model assumes conditions in the HTS microtiter well are similar to conditions at the plasma-to-tissue interface, perfusion-limited tissues (i.e., the chemical concentration in red blood cells, tissues, and plasma come to equilibrium faster than the blood flow), rapid oral absorption (1/hr), 100% bioavailability, and chemicals exit the body through hepatic clearance (utilizing CLint) and passive nonmetabolic renal clearance(GFR*fup).23 For the 3-compartment steady-state model, we assume a steady-state exposure, modeled as a constant infusion for sufficient time to produce a constant predicted plasma concentration. Because we have assumed constant ratios between tissue and free concentration in plasma, tissue partitioning becomes irrelevant. Steady-state concentration can be calculated using one equation11, 13, 28, 29 and includes passive glomerular filtration, liver and gut flows, and the fup and CLint parameters. This steady-state solution is described as the “3-compartment steady-state model”.

Chemical Parameter Values and Comparisons

Of the 8,948 Tox21 chemicals, 495 had in vitro human fup and CLint data from the literature and compiled in the HTTK-package.11, 14, 23, 25, 27, 30–38 Briefly the CLint was measured in primary human hepatocytes and the fup was determined by using rapid equilibrium dialysis. Note that “fub” is currently used in the HTTK package to mean fraction unbound in plasma. In silico TK parameters logP and acidic and basic pKa, were predicted for 8,758 chemicals using ADMET Predictor™ 7.2 (Simulations Plus Inc., Lancaster, California). Organometallics may not be processed adequately in this software. Out of bound parameters were identified by the software and indicated in Table S1. For all models, the default setting for ADMET Predictor was used to determine the various ionization states of each molecule. fup was estimated using ADMET Predictor’s “S+PrUnbnd” expressed as a fraction, and CLint was the sum of CLint predictions across five major metabolizing enzymes CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4. It is our understanding that these model outputs have been unit-adjusted to account for the relative expression level differences of these enzymes in human liver for summations to predict an aggregated metabolic clearance rate. The summed CLint value (μL/min-mg of microsomal protein) was converted to μL/min-106 cells to adjust to the HTTK-package input in vitro CLint parameter.39

| (1) |

Additional conversions for Figure 2B, used 19.6g liver/kg-BW, which was determined from averaging liver weights across four studies:1,561g40; 1,288g41; men:1,130g and women:1,079g42; and 1,800g43 assuming a 70kg adult in all cases.

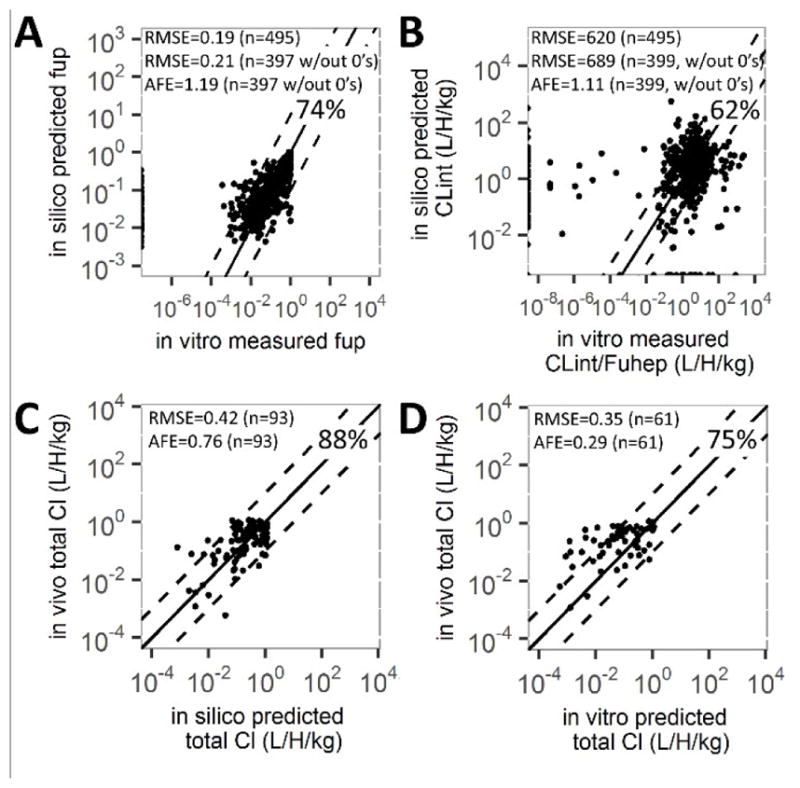

Figure 2. Fraction unbound, hepatic clearance and total clearance prediction comparisons.

fup and CLint parameters were compared between in vitro measured values and in silico estimated for 495 Tox21 chemicals (A, B). In vivo total CLint values were compared to values estimated with the HTTK package using in silico parameters (93 chemicals, C) and in vitro parameters (61 chemicals, D). Solid line is 1:1, dotted lines are 1 log10 difference, with the percentage of data lying within, total number of chemicals (n), root mean squared error (RMSE) and average fold error (AFE) noted. 98 chemicals had no detectible fup from in vitro methods (A). 36 and 78 chemicals had zero CLint values using in silico or in vitro methods, respectively(B).

Root-mean-square error(RMSE) and average fold error (AFE), geometric mean error, metrics, were performed on non-zero data.44

| (2) |

| (3) |

Predicted and observed data are not log-transformed. In vitro CLint was divided by the fraction unbound in hepatocytes (fuhep)45 using the HTTK package in order to compare with in silico CLint (Table S1). Measured human in vivo total CL values44 were compared to estimated total CL using in silico and in vitro values with the HTTK package “calc_total_clearance()” function, where Fhep.assay.correction=1 for in silico estimates (Table S2).

In Vivo Cmax and In Silico Cmax Calculations and Comparison

Measured human in vivo Cmax values with respective therapeutic dosing scenarios (491 Tox21 drugs, 613 unique drug-scenario Cmax outputs), were obtained through the DrugMatrix® database.46 Doses were converted to mg/kg assuming a 70kg adult and 1 mg/kg=37 mg/m2, where applicable.47, 48 These in vivo values were evaluated against the HTTK Cmax outputs to compare and assess the utility of the in silico-derived input parameters(Table S3). For those drugs where dosing scenarios were not provided, HTTK simulations were run assuming one daily dose administered for 28 days. The largest dose was used when a range was given. Cmax calculations were performed with the 3-compartment model and the fraction unbound in hepatocytes correction set to 1.

Cmax/AC50 Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma (PPARγ) and Glucocorticoid Receptor (GR) Case Studies

PPARγ and GR assays (Supporting Information) were chosen because >1 HTS assay represented these pathways and the Tox21/ToxCast assays contained notable PPARγ49–51 and GR37, 38 modulators defined from DrugBank or publications. Five PPARγ agonist assays included: 1)Attagene(ATG); 2)NovaScreen(NVS) cell-free human PPARγ binding; 3–4) two OdysseyThera(OT); and 5)Tox21. For these analyses, all HTS flags were applied, but the efficacy filter was initially not used for demonstration purposes. Compounds active in ≥1 HTS assay with human measured in vivo Cmax values were used to evaluate the approach.

Uncertainty Analysis

The randomForest R-package was used to find parameters associated with the uncertainty in in silico Cmax predictions with respect to in vivo for 3 categories (within 10-fold, over-predicted by >10-fold, under-predicted by >10-fold).52, 53 The 10-fold cut off follows a similar category as has been described when comparing literature to predicted Css.23 Fifteen parameters (Figure 3B) associated with the chemicals (not necessarily used in the TK model predictions) were inputs in the random forest model and were derived from ADMET Predictor or EPI Suite23 (http://www.epa.gov/opptintr/exposure/pubs/episuite.htm (last accessed 22June2015) (Table S5). These fifteen parameters were used in constructing the 50,000 regression trees based upon a subset of the chemicals and descriptors, where each tree was evaluated against chemicals not used in making that tree. Equal sample sizes (n=48) were used for the three categories. Important factors were scored using the Gini index, which compares the performance of trees including a factor against trees without that factor.54

Figure 3. Maximum human plasma concentration prediction comparison.

Cmax was compared between predicted in silico values using the HTTK package and measured human in vivo values gathered in DrugMatrix46, 55 for 491 Tox21 chemicals, 613 dosing scenarios at pharmacologically relevant doses. A) HTTK package with in silico parameters predicted Cmax with RMSE=211.04, AFE=0.80. For most cases, Cmax was predicted within 10-fold (493 scenarios, 80%, black), under-predicted >10-fold (48 scenarios, 8%, blue), and over-predicted >10-fold (72 scenarios, 12%, red). B) Fifteen features used for predicting compound-scenario Cmax over-, under- or within- 10-fold are ordered by importance based on the random forest model. Random forest model performance for estimating confidence is described in the Supporting Information.

Environmental Exposure Data

Mean estimated daily exposures (across all demographic groups) for the Tox21 chemicals were taken from the EPA’s ExpoCast exposure estimates, which were developed using a Bayesian probabilistic modeling methodology and does not explicitly differentiate pharmaceutical exposures.19 For the current work, the most highly exposed group was used as a conservative estimate of exposure. The exposures were available for 7,818 Tox21 chemicals in the current dataset, which subsequently limited the 56,135 active chemical-assay pairs to 49,789 active chemical-assay pairs (3,925 unique chemicals and 746 unique assays) (Table S5).

Dose Predictions of ‘Likely’ and ‘Possible’ Biological Interactions

We predicted equivalent doses from Cmax values using the following classifications: for a ‘likely’ in vivo interaction, Cmax≥AC50, for a ‘possible’ interaction, Cmax≥0.1*AC50 and with a 10-fold safety factor, Cmax≥0.01*AC50. Dose values were calculated using the HTTK 3-compartment steady-state model estimating 3 doses/day. The previously generated random forest model was used to determine higher confidence(within 10x) and lower confidence(over or under-predicted) Cmax values for ‘likely’ and ‘possible’ interactions. The equivalent doses were compared to the ExpoCast exposure estimates (Figures 5–6 and S5).

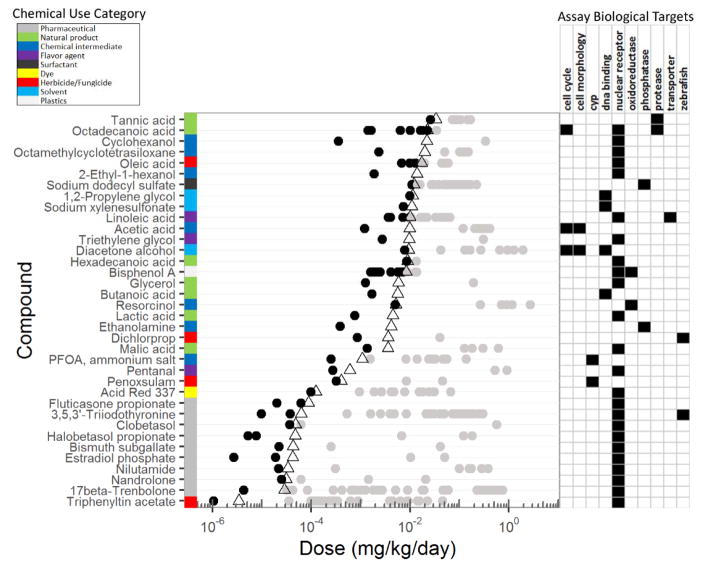

Figure 5. Doses ranges for all active Tox21 compounds eliciting a ‘possible’-to-‘likely’ human in vivo interaction alongside estimated daily exposure.

A) AC50 values, for all 49,789 active Tox21 compound-assays pairs (3,925 unique compounds) with efficacies ≥40% or 2-fold in the HTS assays, were converted to equivalent human doses to elicit a ‘likely’ or ‘possible’ in vivo interaction. These are defined as doses giving maximum in vivo plasma concentrations equal to 1 and 0.1 of the AC50 concentration (‘likely’ and ‘possible’ in vivo interactions, respectively)(gray bars). A chemical can affect multiple assays leading to varying sizes of gray bars. ExpoCast exposure predictions23 are shown in terms of dose per day (black dots). Given for reference, red dots indicate therapeutic daily doses for pharmaceuticals at dosing schema from the DrugMatrix database. B) 56 compounds with overlapping gray bars and black dots (from panel A) indicate potential in vivo biological interaction at estimated environmental exposures.

Figure 6. Doses of compounds eliciting a ‘possible’ human in vivo interaction (Cmax/AC50>0.1) which are lower than estimated daily exposure.

AC50 values for active Tox21/ToxCast compounds with efficacies ≥40% or 2-fold in the HTS assays were converted to equivalent human in vivo doses using exposure scenarios where in vivo Cmax concentrations were equal to 0.1*AC50 to represent ‘possible’ in vivo interactions. ExpoCast median daily exposure estimates23 are shown as open triangles. Predicted doses for chemical-assay pairs are shown (dots) for chemicals which had predicted doses below exposure estimates and had higher confidence in calculating the doses from estimate Cmax values. Biological targets for compounds where doses are lower than estimated exposures (i.e., black data points to the left of the triangles) are shown in the right panel. Gray dots indicate doses needed to activate biology which are higher than estimated exposures. Similar visualizations of all HTS and ExpoCast data in this manuscript can be found in the public IVIVE web application (https://sandbox.ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ivive/).

RESULTS

Estimating TK Properties

To evaluate the utility of in silico-derived fup and CLint parameters, we compared them to in vitro-derived estimates for 495 chemicals (Figure 2). In silico methods predicted in vitro-estimated fup (RMSE=0.21, AFE=1.19 n=397) with 74% of the compounds appearing within 10-fold(Figure 2A). In silico-derived CLint estimates were reasonably predictive of in vitro-derived (RMSE=689, AFE=1.11 n=399); however, only 62% of the compounds fell within 10-fold of the in vitro-derived values(Figure 2B). Several parameter estimates outside the 10-fold range were zero, leading to increased RMSE. For further comparison, total in vivo clearance values estimated using the HTTK package were compared to measured human total in vivo clearance values.44 Total clearance estimates using in silico or in vitro-derived CLint were similarly predictive of in vivo (RMSE=0.42, AFE=0.76, Figure 2C; RMSE=0.35, AFE=0.29, Figure 2D, respectively). Of the 47 chemicals with both types of total clearance predictions, 15 had >10-fold difference between in silico and in vitro values. For these compounds, in vivo values generally fell between the estimates, but were closer to the in silico values (Figure S2).

Predicting Cmax values

These in silico fup and CLint values were applied in the HTTK-package to predict human blood TK parameters, notably Cmax. For comparison, in vivo human Cmax concentrations (613 chemical-dosing scenarios) were available from the DrugMatrix database.46, 55 Cmax predictions were generated applying the in vivo dosing scenarios(i.e., route, dose concentration, duration of exposure) from the DrugMatrix database to parameterize the 3-compartment model. Predicted Cmax values showed RMSE=211.04, AFE=0.80, and 80% of 613 scenarios to be within 10-fold when compared to measured Cmax values(Figure 3A). No apparent bias was observed for dose frequency, but for intramuscular (IM) and intravenous (IV) administration routes 70% of the data (14 out of 21 for IM and 61 out of 86 for IV) were over-predicted(Figure S3), similar to what was previously observed for rat Cmax predictions.23 These data suggest in silico fup and CLint parameters are applicable for use in the IVIVE model.

A random forest classification model was used on residuals between in silico predicted and in vivo measured Cmax values to identify features correlating with Cmax prediction (10-fold boundary). Fifteen features were imported into the model, including in silico predicted Cmax, fup, CLint and physicochemical properties(Figure 3B). We found the top most influential features were CLint, the predicted Cmax, logP, water solubility and fup(Figure 3B). The most extreme outlier from Figure 3A is probucol, which has a logP of 10.7 is the highest in this set. The upper quartile logP value for each of the three categories (under-predicted, within 10-fold, over-predicted) was 5.1, 3.2 and 2.4, respectively. Non-categorical EPI Suite model features (e.g., half-life in air, biotransformation in fish) are surrogates for aggregated chemical class information. These features, while harder to interpret, represent integrated knowledge about significant chemical differences.. The residual prediction model was used to assess confidence in HTS compound-scenarios where no in vivo Cmax data were available, which is dependent on the chemical properties in addition to the chemical-dosing scenarios. Subsequent analyses focused on all chemicals with confidence noted.

Cmax/AC50 Ratios for Two Pharmaceutical Case Studies

We evaluated our hypothesis for translating in vitro assay data to human relevance using Cmax/AC50 ratios with Cmax in vivo measurements and in silico predictions from therapeutic scenarios. PPARγ and GR agonist assays were chosen as case studies since known clinical modulators were screened in Tox21(Figure 4 and S4, respectively). For the PPARγ pathway, 11 of the 14 known PPARγ modulators were classified as at least ‘possible’(Cmax/AC50 ≥0.1) to affect this pathway in humans using either in vivo or in silico Cmax values(Figure 4). Three of the statins (atorvastatin +/−calcium and cerivastatin sodium) were classified as ‘remote’ where literature suggests they can activate PPARγ through a COX-dependent increase in prostaglandin.51 Additionally, several unexpected chemicals were classified as having ‘possible’ interactions, including NSAIDs (e.g., diclofenac, mefenamic acid), PPARα modulators (clofibric acid, gemfibrozil) and progesterone/glucocortioid interaction (mifepristone). The interactions may be non-specific, but in some cases these were expected (e.g., progesterone has been shown to lead to downstream activation of PPARγ in vitro56 and there may be cross-talk between PPARs). Similar findings were seen for the GR pathway (Supporting Information). Together these findings give credibility to the Cmax/AC50 approach for estimating likelihood of in vivo interaction for the Tox21/ToxCast datasets.

Figure 4. Cmax /AC50 ratios for the PPARγ pathway at pharmacological doses.

Compounds with in vivo dosing scenarios and human Cmax values as well as in vitro AC50 values in PPARγ Tox21/ToxCast assays were evaluated for likelihood of in vivo interactions. For 44 active compounds in PPARγ assays, Cmax /AC50 ratios were plotted using the in vivo Cmax from DrugMatrix and in silico estimated Cmax, based on therapeutic external dose. Assays included: 1) Attagene (ATG), 2) NovaScreen (NVS) cell-free human PPARγ binding, 3–4) two OdysseyThera (OT), and 5) Tox21. Chemicals listed were active in at least one assay. Activity across multiple assays are indicated by multiple data points on the same row. Colored data points indicate the accuracy of in silico predicted Cmax values (blue, black, red) vs. in vivo measured Cmax value (grey). Vertical lines at 0.1 and 1 show regions of ‘remote’ (<0.1), ‘possible’ (0.1<X<1) and ‘likely’ (>1) in vivo interaction. Efficacies greater than 40% or 2-fold change are considered high efficacy, and all others are considered low efficacy. (*) indicate known modulators.

Estimating Likelihood of In Vivo Interaction with the Tox21/ToxCast Library

This Cmax /AC50 approach was performed on all Tox21/ToxCast datasets using in silico Cmax values providing context toward quantifying environmental relevance. Environmental exposure data are not available for most the Tox21/ToxCast chemicals; therefore, we determined the equivalent doses required to achieve ‘likely’ and ‘possible’ in vivo interactions using the efficacy filters (49,789 active compound-assay pairs, Figure 5, Table S5). The Cmax values for these scenarios were predicted over a quasi-steady-state (using the 3-compartment steady-state model), providing a more chronic versus acute exposure scenario. The equivalent doses were compared to estimated environmental human exposure predictions from EPA’s ExpoCast program, which was based on a rapid heuristic method using information from NHANES examination of urine analytes in the U.S. population.23 ‘Likely’ interactions occurring at estimated environmental exposures were found for 14 compound-assay scenarios (9 unique CASRN, 12 unique assays) and 114 ‘possible’ interactions (56 unique CASRN, 65 unique assays)(Figure 5B). Only 3/9 and 9/56 of these respective groups of chemicals had measured in vitro parameter data, further supporting the use of in silico estimates. If a 10-fold safety factor was applied to ‘possible’ interactions(i.e., Cmax/AC50≥0.01), 533 interactions(177 unique CASRN, 209 unique assays) are identified. A total of 370 human in vivo daily therapeutic doses for pharmaceuticals are shown for reference(red dots, Figure 5A). Once the TK parameters were established, this method quickly identified interaction likelihood for various cutoffs using the Tox21/ToxCast data.

A closer look at the 56 ‘possible’ level compounds, from Figure 5B, is shown in Figure S5 (all chemicals) and Figure 6. Here, chemical use category, assay biological targets, calculated daily doses at the ‘possible’ interaction level and estimated environmental exposure-doses are shown. For simplicity, Figure 6 shows only 36 of the 56 compounds, for which there was a higher confidence in dose prediction, as determined from the random forest model, and where ‘possible’ interaction dose was less than estimated environmental exposure doses. Most of the ‘possible’ HTS-derived doses for a given compound were higher than estimated exposure-doses(Figure 6, gray dots). The major chemical use categories represented were the natural products and chemical intermediates. The major target affected was the nuclear receptor class, with most responses due to chemical intermediates. Further analyses of these data can be achieved through the public IVIVE web application https://sandbox.ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ivive/).

DISCUSSION

Implications and Novelties of This Approach

This approach provides a novel and intuitive framework to relate environmental chemical exposures rapidly and quantitatively to in vitro bioactivity, helping drive priorities and decision-making. We found that in silico fup and CLint parameters alone, and in a high-throughput 3-compartment model, could ostensibly recapitulate in vitro fup and in vivo total clearance and Cmax values. Cmax/AC50 identified known therapeutic effectors using the 3-compartment model, Tox21/ToxCast data, and in silico parameters. 36 compounds gave higher confidence ‘possible’ human in vivo interaction likelihoods using estimated human environmental exposures. Visualization and data download of daily doses toward in vivo likelihoods of biological effects and AC50 values are provided in a web application (https://sandbox.ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ivive/).

The novelty of this current work 1)considers in vivo plausibility, 2)uses a similar approach to the FDA that is grounded in human clinical effects, 3)relies on in silico TK parameters, and 4)applies the approach to the entire Tox21/ToxCast data, while featuring a conservative concentration estimate and a 3-compartment high-throughput TK model. Previous approaches calculating margins of exposure for ToxCast assays rely on the use of estimated environmental exposure data with limited or no human response data.11, 13, 25 Generally, these approaches have not considered in vivo human clinical response relationships. The Cmax/AC50 approach provides an intuitive framework with established cutoff levels of clinical significance (>0.1 ‘possible’ and >1 ‘likely’) anchored in clinical effects and subsequently extrapolated to environmental compounds where less information is known. The stepwise grounding of the approach provides more confidence to a risk assessment framework. Additionally, this work utilized Cmax which is a more conservative and well-accepted approach to previously used Css values, especially for shorter duration exposures, as many rapidly cleared compounds (e.g., estradiol) may exert their biological effects over a short period that is underestimated with Css levels. Cmax values are commonly used for drug-drug interaction predictions in humans as a conservative estimation of blood concentrations. Additionally, to be conservative for environmental compounds, the Cmax estimates used to derive ‘likely’ and ‘possible’ doses were from a quasi-steady-state approach to ensure maximum possible blood concentrations and were considered from a chronic versus an acute exposure. Our approach employs novel in silico estimates for fup and CLint that were similarly accurate to in vivo data as in vitro-derived parameters, although some of these compounds could have been in the training set which could contribute to the improved predictions with in silico derived estimates. Experimentally-derived in vitro data had a higher number of zero values, which may also contribute to their reduced accuracy. The in silico approach is also less susceptible to interferences such as light sensitivity, adherence of compounds to plastics, or detection limits of analytical instrumentation. Therefore, in silico-derived estimates provide useful data toward a rapid response risk assessment and overcome some of these practical challenges. With the use of in silico parameters, we were able for the first time to evaluate the entire Tox21/ToxCast datasets using IVIVE methods.

Limitations

This simple standardized risk association framework contains assumptions, limitations and uncertainties that serve to guide current use of in silico/in vitro approaches, but will need to be addressed and refined over time. It is important to understand these current constraints which include, 1)HTTK 3-compartment model with in silico parameters, 2)in vitro biology, 3)chemical domain, 4)estimation of exposures, 5)use of a universal formula.

3-Compartment Model

All models within the HTTK R-package allow for rapid IVIVE across thousands of chemicals using several estimated parameters. Both in silico and in vitro-estimated TK parameters determined unrealistically some zero intrinsic clearance values although estimated total clearance compared well to measured values. Likely errors using in silico estimates include utilizing a limited number of hepatic enzymes and in vitro errors include limitations of the in vitro system used, such as potentially low-turnover chemicals or saturated metabolism at the tested concentrations. In addition, the CYP enzymes in the in silico estimations may not be the major metabolizing pathways for some Tox21/ToxCast chemicals, which could include Phase II enzymes. The current work could be further refined by first estimating the extent of metabolism57 or the most likely route of metabolism58 using developed predictive models as examples. Further, the calculations assumed a standardized 70kg human model (with no metabolic variation) for simplicity. The 10-fold in silico TK bounds may not be practical for pharmaceutical applications or in Css models (versus Cmax models) since they rely more heavily on accurate CLint values. The HTTK package with TK parameters serves as fit-for-purpose model that can quickly and readily screen through hundreds-to-thousands of chemicals. Alternative models incorporating saturable metabolism/transport, pH gradients, additional compartments59, and population variability12 exist with lower throughput which can be used in follow-up detailed analyses.

In Vitro Biology

We took a conservative approach for human health protection to identify as many ‘possible’ chemical-biological in vivo human interactions from the HTS data under certain criteria. These criteria include ≥40% or 2-fold efficacy, in vitro interaction without cytotoxicity (for Tox21 assays), and the concentration-response curve-fitting passing a specified quality threshold. Even with these considerations, single assay measurements do not necessarily equate to adverse effects in vivo. Efforts to identify true biological interactions, such as the multi-faceted estrogen signaling pathway60 utilizing several HTS assays, are helping to eliminate false positives and can be readily implemented with this approach. In HTS assays, compounds may be falsely identified due to effects such as cross contamination from compound delivery systems, autofluorescence, detergent behavior that disrupts the assay, or lack of cell membrane barriers (as in the NovaScreen panel61), and thus would need confirmatory screening. The analyses herein are focused on prioritizing compounds with observed biological effect. False negatives are not specifically addressed, but could occur due to differential in vitro metabolism, poor chemical quality, chemical volatility, or the appropriate biology or assay was not screened. Additionally, the current approach assumes the nominal concentration is the effective concentration. Theoretical models on large numbers of chemicals indicate a cellular or membrane concentration may better represent the effective concentration62, 63 and should be examined in future evaluations. Even with these caveats, this approach evaluates and curates thousands of data points to a manageable number for further detailed investigation through literature review and/or further targeted testing. New phases of Tox21/ToxCast programs will include toxicogenomic approaches to eliminate some of the challenges associated with pathway/target-specific screening. Absence of species and genetic variability is also a limitation, but can potentially be addressed through efforts, such as the human lymphoblastoid cell models and the mouse diversity outcross.64

Training Set Evaluation

Pharmaceuticals comprise the training set for ADMET-Predictor’s TK models and the Cmax comparisons due to the availability of associated human TK information. Only 4 compounds from Figure 6 (acetic acid, bismuth subgallate, octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane (D4), and triphenyltin acetate) produced out-of-domain QSAR fup values as defined in the software, but were used in this analyses as an approximation where no information was available. Furthermore, we compared the 15 parameters used in identifying lower confidence Cmax scenarios from the 491 pharmaceuticals in the training set to the rest of the chemical set. LogP was a top factor in the random forest model and under-predicted compounds tended to have higher logP values, which suggests high logP compound concentrations are more difficult to predict. Specifically, it is thought that PFOA and PFOS are actively resorbed by the kidney, a process not captured by the current HTTK model.11 Additionally, four of the 15 parameters (Cmax, bioconcentration factor, half-life in air, and biotransformation half-life in fish) were >10-fold different, based on the mean values. These parameters indicate an aggregation of chemical features which, when taken together, should be explored to further probe the limitations of the chemical space coverage.

Estimation of Exposures

For the majority of the Tox21 10k library, the only available non-pharmaceutical exposures were estimates.19 Environmental and occupational exposure data are limited, but can ground-truth predictions. For example, estimated human daily exposure to octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane (D4) from measured contamination in Spanish market fish is 8.36E-04 mg/kg/day65 versus ExpoCast estimate of 1.98E-02 mg/kg/day, and predicted ‘possible’ interaction dose using HTS data of 2.31E-03 mg/kg/day. Occupational exposures can be much higher. One study showed maximum blood concentrations of 2-methyl-4,6-dinitrophenol after occupational exposures at 348μM with systemic yellowing of the hands, nails and hair.66 HTS AC50 values ranged from 0.8 to 107μM, making these targets ‘likely’ to be perturbed in vivo with this exposure scenario. Manually gathering exposure data goes beyond the scope of this current publication, but efforts such as the NHANES and EPA’s ExpoCast (https://www.epa.gov/chemical-research/rapid-chemical-exposure-and-dose-research) are dedicated to capturing, measuring, and publicly disseminating environmental exposure information which will allow easier comparisons across multiple estimates and provide exposure and susceptible population variability.

Universal Formula

A Cmax/AC50 type approach has been used by the FDA to evaluate potential drug-drug interactions with respect to cytochromes P450 and p-glycoprotein. Further refinement includes adjusting cutoff scenarios and efficacy limits tailored to the biological target or application of interest. For pharmaceutical development, chemical-assay pairs with ‘likely’ interactions on the therapeutic target of interest may only be evaluated when Cmax/AC50 is ≫118, whereas for environmental situations, ratios >0.1 (‘possible’ interactions) with or without a safety factor may be warranted. Alternatives to the model include incorporating AUC67 and alternative HTS assay outputs such as points of departure, AC10 or area under the curve can be incorporated to evaluate outcome and ranking similarity. The nature of the biological interaction will likely impact the utility of either Cmax or AUC for a given chemical-target interaction. For example, Cmax would be more relevant for transient interactions sufficient to elicit a phenotype, whereas AUC may be more relevant for interactions requiring sustained activation to elicit a phenotype.

This approach toward predicting likelihood of in vivo interaction using the Tox21/ToxCast HTS data is promising. This method can prioritize compounds in a screening level risk assessment framework by first evaluating the likelihood of in vivo interactions, which then can be compared against exposure data. A publicly available web application is available to perform these analyses in real-time (https://sandbox.ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ivive/). As these models are evaluated and tested, they will become tailored and refined for fit-for-purpose applications. It is important to note that HTTK, HTS assays, exposure and in silico prediction models will additionally continue to improve with the generation of more data, specifically publicly available data on thousands of compounds. A specific example is bisphenol A, which has sufficient information to develop a detailed PBTK model, refined environmental exposure estimates, biomonitoring data, and in vitro data to perform an integrated and more developed exposure/risk characterization.68

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Joshua Addington for his help in programming the web application, Ben Schuler for his graphics advice, and Drs. Doris Smith and Richard Judson for the chemical use categories. We also would like to thank Drs. John Bucher, Robert D. Clark, Keith Houck, Michael Hughes, Scott Masten, Richard Paules, Russell Thomas, and Nigel Walker for their helpful comments while reviewing the manuscript.

Footnotes

DISCLAIMER

This manuscript has been cleared for publication by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Research and Development and the NIEHS Division of the National Toxicology Program. However, it may not necessarily reflect official Agency policy, and reference to commercial products or services does not constitute endorsement. The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Data tables including CLint and fup comparisons, Cmax comparisons, filtered Tox21/ToxCast data, and daily dose estimates from the Tox21/ToxCast data to produce ‘likely’, ‘possible’ and ‘possible’ with 10x safety factor in vivo interactions. Clarifying figures further illustrate Tox21 and ToxCast data processing, differences in Cmax estimates, route of exposure and data for chemicals with ‘possible’ daily dose estimates less than estimated exposures regardless of confidence-level. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Judson R, Richard A, Dix DJ, Houck K, Martin M, Kavlock R, Dellarco V, Henry T, Holderman T, Sayre P, Tan S, Carpenter T, Smith E. The toxicity data landscape for environmental chemicals. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2009;117(5):685–95. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tice RR, Austin CP, Kavlock RJ, Bucher JR. Improving the human hazard characterization of chemicals: a Tox21 update. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2013;121(7):756–65. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kavlock RJ, Austin CP, Tice RR. Toxicity testing in the 21st century: implications for human health risk assessment. Risk Analysis. 2009;29(4):485–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01168.x. discussion 492–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sipes NS, Martin MT, Reif DM, Kleinstreuer NC, Judson RS, Singh AV, Chandler KJ, Dix DJ, Kavlock RJ, Knudsen TB. Predictive models of prenatal developmental toxicity from ToxCast high-throughput screening data. Toxicological Sciences. 2011;124(1):109–27. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin MT, Knudsen TB, Reif DM, Houck KA, Judson RS, Kavlock RJ, Dix DJ. Predictive model of rat reproductive toxicity from ToxCast high throughput screening. Biology of Reproduction. 2011;85(2):327–39. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.090977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Judson RS, Houck KA, Kavlock RJ, Knudsen TB, Martin MT, Mortensen HM, Reif DM, Rotroff DM, Shah I, Richard AM, Dix DJ. In vitro screening of environmental chemicals for targeted testing prioritization: the ToxCast project. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2010;118(4):485–92. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kleinstreuer NC, Judson RS, Reif DM, Sipes NS, Singh AV, Chandler KJ, Dewoskin R, Dix DJ, Kavlock RJ, Knudsen TB. Environmental impact on vascular development predicted by high-throughput screening. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2011;119(11):1596–603. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reif DM, Martin MT, Tan SW, Houck KA, Judson RS, Richard AM, Knudsen TB, Dix DJ, Kavlock RJ. Endocrine profiling and prioritization of environmental chemicals using ToxCast data. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2010;118(12):1714–20. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Auerbach S, Filer D, Reif D, Walker V, Holloway AC, Schlezinger J, Srinivasan S, Svoboda D, Judson R, Bucher JR, Thayer KA. Prioritizing Environmental Chemicals for Obesity and Diabetes Outcomes Research: A Screening Approach Using ToxCast High Throughput Data. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2016;124(8):1141–1154. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1510456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wetmore BA, Wambaugh JF, Ferguson SS, Li L, Clewell HJ, 3rd, Judson RS, Freeman K, Bao W, Sochaski MA, Chu TM, Black MB, Healy E, Allen B, Andersen ME, Wolfinger RD, Thomas RS. Relative impact of incorporating pharmacokinetics on predicting in vivo hazard and mode of action from high-throughput in vitro toxicity assays. Toxicological Sciences. 2013;132(2):327–46. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wetmore BA, Wambaugh JF, Ferguson SS, Sochaski MA, Rotroff DM, Freeman K, Clewell HJ, 3rd, Dix DJ, Andersen ME, Houck KA, Allen B, Judson RS, Singh R, Kavlock RJ, Richard AM, Thomas RS. Integration of dosimetry, exposure, and high-throughput screening data in chemical toxicity assessment. Toxicological Sciences. 2012;125(1):157–74. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wetmore BA, Allen B, Clewell HJ, 3rd, Parker T, Wambaugh JF, Almond LM, Sochaski MA, Thomas RS. Incorporating population variability and susceptible subpopulations into dosimetry for high-throughput toxicity testing. Toxicological Sciences. 2014;142(1):210–24. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rotroff DM, Wetmore BA, Dix DJ, Ferguson SS, Clewell HJ, Houck KA, Lecluyse EL, Andersen ME, Judson RS, Smith CM, Sochaski MA, Kavlock RJ, Boellmann F, Martin MT, Reif DM, Wambaugh JF, Thomas RS. Incorporating human dosimetry and exposure into high-throughput in vitro toxicity screening. Toxicological Sciences. 2010;117(2):348–58. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wambaugh J, Pearce R, Davis J, Sipes N. httk: High-Throughput Toxicokinetics. 2016. R package version 1.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pearce RG, Setzer RW, Strope CL, Sipes NS, Wambaugh JF. httk: R Package for High-Throughput Toxicokinetics. Journal of Statistical Software. 2017;79(4):1–26. doi: 10.18637/jss.v079.i04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Food and Drug Administration. Draft Guidance for Industry: Drug Interaction Studies: Study Design, Data Analysis, and Implications for Dosing and Labeling. Rockville, MD: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Persson M, Loye AF, Mow T, Hornberg JJ. A high content screening assay to predict human drug-induced liver injury during drug discovery. Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods. 2013;68(3):302–13. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fallahi-Sichani M, Honarnejad S, Heiser LM, Gray JW, Sorger PK. Metrics other than potency reveal systematic variation in responses to cancer drugs. Nature Chemical Biology. 2013;9(11):708–14. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wambaugh JF, Wang A, Dionisio KL, Frame A, Egeghy P, Judson R, Setzer RW. High throughput heuristics for prioritizing human exposure to environmental chemicals. Environmental science & technology. 2014;48(21):12760–7. doi: 10.1021/es503583j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsieh JH, Sedykh A, Huang R, Xia M, Tice RR. A Data Analysis Pipeline Accounting for Artifacts in Tox21 Quantitative High-Throughput Screening Assays. Journal of biomolecular screening. 2015;20(7):887–97. doi: 10.1177/1087057115581317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsieh JH. Accounting Artifacts in High-Throughput Toxicity Assays. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2016;1473:143–52. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6346-1_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang R, Xia M, Cho MH, Sakamuru S, Shinn P, Houck KA, Dix DJ, Judson RS, Witt KL, Kavlock RJ, Tice RR, Austin CP. Chemical genomics profiling of environmental chemical modulation of human nuclear receptors. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2011;119(8):1142–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wambaugh JF, Wetmore BA, Pearce R, Strope C, Goldsmith R, Sluka JP, Sedykh A, Tropsha A, Bosgra S, Shah I, Judson R, Thomas RS, Woodrow Setzer R. Toxicokinetic Triage for Environmental Chemicals. Toxicological Sciences. 2015;147(1):55–67. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfv118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wetmore BA, Wambaugh JF, Allen B, Ferguson SS, Sochaski MA, Setzer RW, Houck KA, Strope CL, Cantwell K, Judson RS, LeCluyse E, Clewell HJ, Thomas RS, Andersen ME. Incorporating High-Throughput Exposure Predictions With Dosimetry-Adjusted In Vitro Bioactivity to Inform Chemical Toxicity Testing. Toxicological Sciences. 2015;148(1):121–36. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfv171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmitt W. Corrigendum to: “General approach for the calculation of tissue to plasma partition coefficients” [Toxicology in Vitro 22 (2008) 457–467] Toxicology in Vitro. 2008;22:1666. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmitt W. General approach for the calculation of tissue to plasma partition coefficients. Toxicology In Vitro. 2008;22(2):457–67. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wetmore BA. Quantitative in vitro-to-in vivo extrapolation in a high-throughput environment. Toxicology. 2015;332:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilkinson GR, Shand DG. Commentary: a physiological approach to hepatic drug clearance. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1975;18(4):377–90. doi: 10.1002/cpt1975184377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lau YY, Sapidou E, Cui X, White RE, Cheng KC. Development of a novel in vitro model to predict hepatic clearance using fresh, cryopreserved, and sandwich-cultured hepatocytes. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2002;30(12):1446–54. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.12.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naritomi Y, Terashita S, Kagayama A, Sugiyama Y. Utility of hepatocytes in predicting drug metabolism: comparison of hepatic intrinsic clearance in rats and humans in vivo and in vitro. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2003;31(5):580–8. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.5.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ito K, Houston JB. Comparison of the use of liver models for predicting drug clearance using in vitro kinetic data from hepatic microsomes and isolated hepatocytes. Pharmaceutical research. 2004;21(5):785–92. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000026429.12114.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Obach RS. Prediction of human clearance of twenty-nine drugs from hepatic microsomal intrinsic clearance data: An examination of in vitro half-life approach and nonspecific binding to microsomes. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 1999;27(11):1350–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Obach RS, Lombardo F, Waters NJ. Trend analysis of a database of intravenous pharmacokinetic parameters in humans for 670 drug compounds. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2008;36(7):1385–405. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.020479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shibata Y, Takahashi H, Chiba M, Ishii Y. Prediction of hepatic clearance and availability by cryopreserved human hepatocytes: an application of serum incubation method. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2002;30(8):892–6. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.8.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tonnelier A, Coecke S, Zaldivar JM. Screening of chemicals for human bioaccumulative potential with a physiologically based toxicokinetic model. Archives of toxicology. 2012;86(3):393–403. doi: 10.1007/s00204-011-0768-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGinnity DF, Soars MG, Urbanowicz RA, Riley RJ. Evaluation of fresh and cryopreserved hepatocytes as in vitro drug metabolism tools for the prediction of metabolic clearance. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2004;32(11):1247–53. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.000026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paixao P, Gouveia LF, Morais JA. Prediction of the human oral bioavailability by using in vitro and in silico drug related parameters in a physiologically based absorption model. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2012;429(1–2):84–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barter ZE, Bayliss MK, Beaune PH, Boobis AR, Carlile DJ, Edwards RJ, Houston JB, Lake BG, Lipscomb JC, Pelkonen OR, Tucker GT, Rostami-Hodjegan A. Scaling factors for the extrapolation of in vivo metabolic drug clearance from in vitro data: reaching a consensus on values of human microsomal protein and hepatocellularity per gram of liver. Current drug metabolism. 2007;8(1):33–45. doi: 10.2174/138920007779315053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Molina DK, DiMaio VJ. Normal organ weights in men: part II-the brain, lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys. The American journal of forensic medicine and pathology. 2012;33(4):368–72. doi: 10.1097/PAF.0b013e31823d29ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Molina DK, DiMaio VJ. Normal Organ Weights in Women: Part II-The Brain, Lungs, Liver, Spleen, and Kidneys. The American journal of forensic medicine and pathology. 2015;36(3):182–7. doi: 10.1097/PAF.0000000000000175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan SC, Liu CL, Lo CM, Lam BK, Lee EW, Wong Y, Fan ST. Estimating liver weight of adults by body weight and gender. World journal of gastroenterology. 2006;12(14):2217–22. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i4.2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davies B, Morris T. Physiological parameters in laboratory animals and humans. Pharmaceutical research. 1993;10(7):1093–5. doi: 10.1023/a:1018943613122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hallifax D, Foster JA, Houston JB. Prediction of human metabolic clearance from in vitro systems: retrospective analysis and prospective view. Pharmaceutical research. 2010;27(10):2150–61. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0218-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kilford PJ, Gertz M, Houston JB, Galetin A. Hepatocellular binding of drugs: correction for unbound fraction in hepatocyte incubations using microsomal binding or drug lipophilicity data. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2008;36(7):1194–7. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.020834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.NTP DrugMatrix®. [January 22, 2015]; https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/drugmatrix/index.html.

- 47.Freireich EJ, Gehan EA, Rall DP, Schmidt LH, Skipper HE. Quantitative comparison of toxicity of anticancer agents in mouse, rat, hamster, dog, monkey, and man. Cancer chemotherapy reports Part 1. 1966;50(4):219–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Estimating the Maximum Safe Starting Dose in Initial Clinical Trials for Therapeutics in Adult Healthy Volunteers. Rockville, MD: 2005. p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kunishima C, Inoue I, Oikawa T, Nakajima H, Komoda T, Katayama S. Activating effect of benzbromarone, a uricosuric drug, on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. PPAR Research. 2007;2007:36092. doi: 10.1155/2007/36092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Puhl AC, Milton FA, Cvoro A, Sieglaff DH, Campos JC, Bernardes A, Filgueira CS, Lindemann JL, Deng T, Neves FA, Polikarpov I, Webb P. Mechanisms of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma regulation by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Nuclear Receptor Signaling. 2015;13:e004. doi: 10.1621/nrs.13004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yano M, Matsumura T, Senokuchi T, Ishii N, Murata Y, Taketa K, Motoshima H, Taguchi T, Sonoda K, Kukidome D, Takuwa Y, Kawada T, Brownlee M, Nishikawa T, Araki E. Statins activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma through extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent cyclooxygenase-2 expression in macrophages. Circulation Research. 2007;100(10):1442–51. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000268411.49545.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Breiman L. Random forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45(1):5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liaw A, Wiener M. Classification and Regression by randomForest. R News. 2002;2(3):18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Archer KJ, Kirnes RV. Empirical characterization of random forest variable importance measures. Comput Stat Data An. 2008;52(4):2249–2260. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ganter B, Tugendreich S, Pearson CI, Ayanoglu E, Baumhueter S, Bostian KA, Brady L, Browne LJ, Calvin JT, Day GJ, Breckenridge N, Dunlea S, Eynon BP, Furness LM, Ferng J, Fielden MR, Fujimoto SY, Gong L, Hu C, Idury R, Judo MS, Kolaja KL, Lee MD, McSorley C, Minor JM, Nair RV, Natsoulis G, Nguyen P, Nicholson SM, Pham H, Roter AH, Sun D, Tan S, Thode S, Tolley AM, Vladimirova A, Yang J, Zhou Z, Jarnagin K. Development of a large-scale chemogenomics database to improve drug candidate selection and to understand mechanisms of chemical toxicity and action. Journal of Biotechnology. 2005;119(3):219–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim J, Sato M, Li Q, Lydon JP, Demayo FJ, Bagchi IC, Bagchi MK. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma is a target of progesterone regulation in the preovulatory follicles and controls ovulation in mice. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2008;28(5):1770–82. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01556-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hosey CM, Benet LZ. Predicting the extent of metabolism using in vitro permeability rate measurements and in silico permeability rate predictions. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2015;12(5):1456–66. doi: 10.1021/mp500783g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lombardo F, Obach RS, Varma MV, Stringer R, Berellini G. Clearance mechanism assignment and total clearance prediction in human based upon in silico models. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2014;57(10):4397–405. doi: 10.1021/jm500436v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ludovico P, Rodrigues F, Almeida A, Silva MT, Barrientos A, Corte-Real M. Cytochrome c release and mitochondria involvement in programmed cell death induced by acetic acid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2002;13(8):2598–606. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E01-12-0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Judson RS, Magpantay FM, Chickarmane V, Haskell C, Tania N, Taylor J, Xia M, Huang R, Rotroff DM, Filer DL, Houck KA, Martin MT, Sipes N, Richard AM, Mansouri K, Setzer RW, Knudsen TB, Crofton KM, Thomas RS. Integrated Model of Chemical Perturbations of a Biological Pathway Using 18 In Vitro High-Throughput Screening Assays for the Estrogen Receptor. Toxicological Sciences. 2015;148(1):137–54. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfv168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sipes NS, Martin MT, Kothiya P, Reif DM, Judson RS, Richard AM, Houck KA, Dix DJ, Kavlock RJ, Knudsen TB. Profiling 976 ToxCast chemicals across 331 enzymatic and receptor signaling assays. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2013;26(6):878–95. doi: 10.1021/tx400021f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Armitage JM, Wania F, Arnot JA. Application of mass balance models and the chemical activity concept to facilitate the use of in vitro toxicity data for risk assessment. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48(16):9770–9. doi: 10.1021/es501955g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fischer FC, Henneberger L, Konig M, Bittermann K, Linden L, Goss KU, Escher BI. Modeling Exposure in the Tox21 in Vitro Bioassays. Chem Res Toxicol. 2017;30(5):1197–1208. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.7b00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Abdo N, Xia M, Brown CC, Kosyk O, Huang R, Sakamuru S, Zhou YH, Jack JR, Gallins P, Xia K, Li Y, Chiu WA, Motsinger-Reif AA, Austin CP, Tice RR, Rusyn I, Wright FA. Population-based in vitro hazard and concentration-response assessment of chemicals: the 1000 genomes high-throughput screening study. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2015;123(5):458–66. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sanchis J, Llorca M, Pico Y, Farre M, Barcelo D. Volatile dimethylsiloxanes in market seafood and freshwater fish from the Xuquer River, Spain. Science of The Total Environment. 2016;545–546:236–43. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jastroch S, Knoll W, Lange B, Riemer F, Thiele E. Results of studies on the exposure of agricultural chemists to dinitro-o-cresol (DNOC) Zeitschrift für die Gesamte Hygiene und Ihre Grenzgebiete. 1978;24(5):340–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Food and Drug Administration. Draft Guidance for Industry: Drug Interaction Studies: Study Design, Data Analysis, Implications for Dosing, and Labeling Recommendations. Rockville, MD: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sarigiannis DA, Karakitsios SP, Handakas E, Simou K, Solomou E, Gotti A. Integrated exposure and risk characterization of bisphenol-A in Europe. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2016;98(Pt B):134–147. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2016.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.