Abstract

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common cardiac disease in aging populations with high comorbidity and mortality. Sex differences in AF epidemiology are insufficiently understood.

Methods

In N=79,793 individuals without AF diagnosis at baseline (median age 49.6 years, age range 24.1-97.6 years, 51.7% women) from four community-based European studies (FINRISK, DanMONICA, Moli-sani, Northern Sweden) of the BiomarCaRE consortium, we examined AF incidence, its association with mortality, common risk factors, biomarkers and prevalent cardiovascular disease, and their attributable risk by sex. Median follow-up time was 12.6 (to a maximum of 28.2) years.

Results

Fewer AF cases were observed in women, N=1,796 (4.4%) than in men, N=2,465 (6.4%). Cardiovascular risk factor distribution and lipid profile at baseline were less beneficial in men compared to women and cardiovascular disease was more prevalent in men. Cumulative incidence increased markedly after the age of 50 years in men and after 60 years in women. The lifetime risk was similar (more than 30%) for both sexes. Subjects with incident AF had a 3.5-fold risk of death compared to those without AF. Multivariable-adjusted models showed sex differences for the association of body mass index (BMI) and AF, hazard ratio (HR) per standard deviation (SD) increase 1.18, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.12 to 1.23 in women versus 1.31, 95% CI 1.25 to 1.38 in men; interaction P value 0.001. Total cholesterol was inversely associated with incident AF with a greater risk reduction in women, HR per SD 0.86, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.90 versus 0.92, 95% CI 0.88 to 0.97 in men, interaction P value 0.023. No sex differences were seen for C-reactive protein and N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide.

The population attributable risk of all risk factors combined was 41.9% in women and 46.0% in men. About 20% of the risk was observed for BMI.

Conclusions

Lifetime risk of AF was high and AF was strongly associated with increased mortality both in women and men. BMI explained the largest proportion of AF risk. Observed sex differences in the association of BMI and total cholesterol with AF need to be evaluated for underlying pathophysiology and relevance to sex-specific prevention strategies.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, sex, epidemiology, cohort, biomarkers risk assessment, mortality

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common cardiac disease that increases the risk of morbidity and mortality in aging women and men.1–3 Considerable sex differences in prevalence, incidence, and mortality have been reported.2,4 AF prevalence in middle-aged and older community cohorts is almost twice as high in men than in women.5–7 The increasing prevalence of AF and subsequent public health and economic burden require research efforts to understand sex differences in disease distribution and risk factor associations.5 The onset of AF diminishes the survival advantage in women.8 Risk of adverse outcomes in AF also appears to differ by sex, e.g. stroke risk is higher in women with AF.9 Consistently reported risk factors for AF such as obesity, arterial hypertension, blood lipid profile, diabetes, smoking, alcohol consumption, and prevalent cardiovascular diseases, show differential distributions by sex and thus need to be considered as possible explanations for observed differences in AF epidemiology.10 Furthermore, biomarkers related to the disease such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and B-type natriuretic peptide (Nt-proBNP) are known to differ by sex,11,12 and may be differentially associated with AF risk.

Despite the increasing public health importance of AF, sex-specific disease distributions and associations of clinical risk factors and cardiac biomarkers with AF have received limited attention. Our study comprises a subset of the BiomarCaRE (Biomarker for Cardiovascular Risk Assessment in Europe) consortium, which provides information on the epidemiology of AF and its risk factors in European community cohorts.13 Our objective was to systematically examine sex differences in AF incidence, and in the association of AF with mortality, classical cardiovascular risk factors and biomarkers in Europe. We also examined sex differences in population attributable risks for AF derived from the classical risk factors.

Methods

Study Sample

The present study is a substudy of the BiomarCaRE consortium.13 Current analyses include BiomarCaRE cohorts with available information on AF status at baseline and follow-up (DanMONICA, FINRISK, Moli-sani and Northern Sweden), totaling N=79,793 individuals. All individuals gave informed consent prior to study inclusion. The cohorts were based on representative population samples with baseline examinations between 1982 and 2010. Individuals with self-reported and/or physician-diagnosed history of AF/atrial flutter and/or prior ICD-10 coding for AF/atrial flutter and/or AF/atrial flutter on the baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) were defined as having prevalent AF and excluded from all analyses (N=687). Details on the enrolment and follow-up procedures of each study are provided in the Supplemental Material. Missing data were handled by available case analyses.

Risk Factors and Follow-Up

Risk factor information was available from the baseline visits. Body mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure, and total cholesterol were measured locally by routine methods, and along with daily smoking, prevalent diabetes, anti-hypertensive medication, history of stroke, and myocardial infarction centrally harmonized in the MORGAM (MONICA Risk, Genetics, Archiving and Monograph) project.14 These clinical variables have consistently been related to AF and are part of risk prediction schemes.15 Average alcohol consumption was assessed in grams per day and according to the WHO average volume drinking categories (http://www.who.int/publications/cra/en/). As ‘abstainers’ could not be separated from the ‘average drinking category I’, we merged these two categories. The diagnosis of AF was based on study ECG tracings, questionnaire information, national hospital discharge registry data, including data on ambulatory visits to specialized hospitals. Additionally, causes of death registry data were screened for incident AF as a comorbidity of individuals that died for other causes. Mortality data were derived from central death registries. The last follow-up was between 2010 and 2011 in the various cohorts.

Biomarker measurement

Biomarker measurements from stored blood samples were available for some of the cohorts (Supplementary Table 1). In N=37,902 individuals, CRP was determined by latex immunoassay CRP16 (Abbott, Architect c8000), with intraassay and interassay coefficients of variation of 0.93 and 0.83.16 In N=29,038 participants Nt-proBNP was measured on the ELECSYS 2010 platform using an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA, Roche Diagnostics). The analytical range is given as 5–35.000 ng/L. Intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 2.58 and 1.38.

Local Ethics Committees have approved all participating studies. The authors had full access to the data and take responsibility for its integrity. All authors have read and agreed to the manuscript as written.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were presented as median (25th, 75th percentile) and binary variables as absolute and relative frequencies. Cumulative incidence curves for AF and death without AF as competing risks were computed using the Aalen-Johansen estimator.17 To examine the association of AF and all-cause mortality a sex and cohort stratified Cox regression for all-cause mortality with AF during follow-up as a time dependent covariate was computed. Total cholesterol, BMI, daily smoking, diabetes, systolic blood pressure and antihypertensive medication were used as time fixed covariates as they are only available at baseline. For these covariates and AF, a sex interaction was included in the model to allow for the effect of the covariate to vary by sex. Age was used as the time scale in all models.18

To study the associations of AF risk factors with time to AF for women and men, sex and cohort stratified Cox regressions were performed. First, for each risk factor a Cox model was computed. Then a model including simultaneously BMI, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, diabetes, daily smoking, and antihypertensive medication was fitted. Finally, each of the variables alcohol consumption, history of stroke, history of myocardial infarction, CRP, and Nt-proBNP were added in turn to this last model. For all covariates a sex interaction was included in each model. If a model included systolic blood pressure, then antihypertensive medication was included in the model. Relative risk ratios (RRR) for the women:men ratio of hazard ratios and population attributable risks (PARs) for incident AF were calculated.

For the PAR calculations, categorization of the continuous variables BMI (<25 kg/m2, 25 to < 30 kg/m2, ≥30kg/m2), systolic blood pressure (<120 mm Hg, 120 to <140 mm Hg, 140 to <160 mm Hg, ≥160 mm Hg), and total cholesterol (cut-off 200 mg/dL=5.17 mmol/L) were performed. Average daily alcohol consumption was categorized based on calculated alcohol intake as follows: category I: for women 0-19.99g alcohol daily, for men 0-39.99 g; category II: for women 20-39.99 g, for men 40-59.99 g; category III: for women ≥40 g, for men ≥60 g.

In secondary analyses we evaluated the association of waist-to-hip ratio and the height and weight component of BMI, with time-to-AF following similar Cox modelling protocols.

All statistical methods were implemented in R statistical software version 3.3.3 (www.R-project.org). A more detailed description of the statistical methods is provided in the Supplemental Material.

Results

Our study sample had an overall median age of 49.6 years, age range 24.1 to 97.6 years at baseline, about half of the participants (48.3%) were men. Median age was similar for women and men (49.2 versus 50.0 years) The baseline characteristics of the sample by sex are provided in Table 1. Risk factor distributions were more favorable in women who had lower BMI and systolic blood pressure than men. Women smoked less, consumed lower amounts of alcohol, and had lower levels of diabetes than men. Total cholesterol and CRP levels were similar in both sexes. Median Nt-proBNP concentrations were higher in women than in men. Study characteristics by cohort are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the sample by sex.

| Variable | Women N=41,226 |

Men N=38,567 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at examination (years) | 49.2 (39.5, 59.0) | 50.0 (39.9, 59.9) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.7 (22.8, 29.5) | 26.7 (24.3, 29.4) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 130 (118, 147) | 136 (125, 150) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes No. (%) | 1818 (4.4) | 2075 (5.4) | <0.001 |

| Daily smoking No. (%) | 8527 (20.8) | 10947 (28.6) | <0.001 |

| Antihypertensive medication No. (%) | 6718 (17.0) | 6198 (16.9) | 0.49 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.6 (4.9, 6.4) | 5.6 (4.9, 6.4) | <0.001 |

| Average daily alcohol consumption (g) | 1.0 (0, 6.0) | 8.0 (1.0, 23.0) | <0.001 |

| Average drinking category I No. (%) | 37886 (94.7) | 32827 (88.1) | <0.001 |

| Average drinking category II No. (%) | 1781 (4.5) | 2791 (7.5) | <0.001 |

| Average drinking category III No. (%) | 342 (0.9) | 1663 (4.5) | <0.001 |

| History of stroke No. (%) | 445 (1.1) | 668 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| History of myocardial infarction No. (%) | 484 (1.2) | 1567 (4.1) | <0.001 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 1.4 (0.7, 3.2) | 1.4 (0.7, 2.9) | 0.51 |

| Nt-proBNP (ng/mL) | 59 (35, 100) | 37 (20, 76) | <0.001 |

Continuous variables are presented as median (25th, 75th percentile), binary variables as absolute and relative frequencies. The P value given is for the Mann-Whitney test or the Chi-square test. N incident AF: All=4,261 (5.3%), women=1,796 (4.4%), men=2,465 (6.4%).

Average drinking categories based on pure alcohol intake: category I, for women 0-19.99 g/day, for men 0-39.99 g/day; category II, for women 20-39.99 g/day, for men 40-59.99 g/day; category III, for women ≥40 g/day, for men ≥60 g/day.

BMI stands for body mass index, Nt-proBNP for N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide.

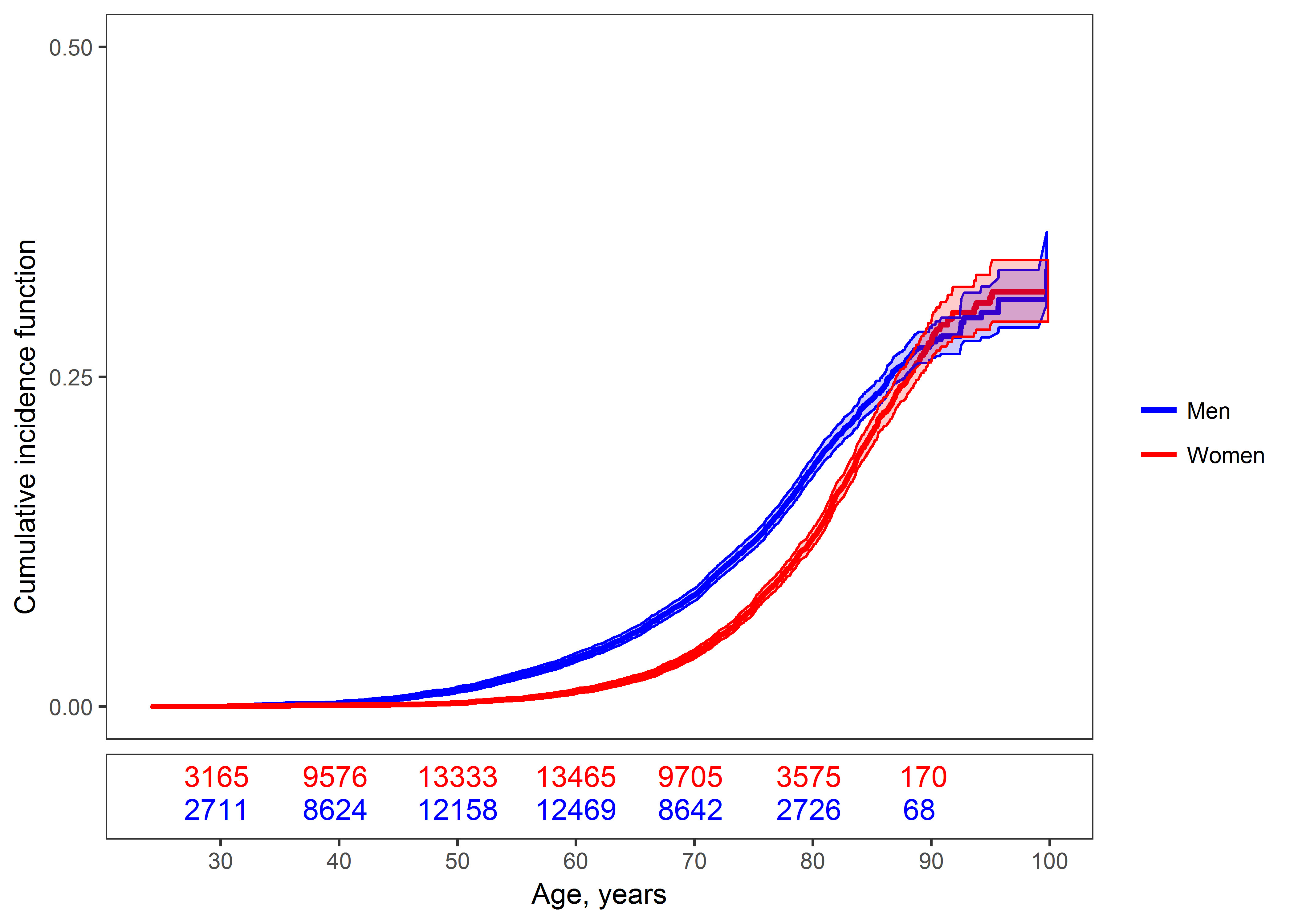

Over a median follow-up of 12.4 years, range 0-29 years, fewer incident AF cases occurred in women, N=1,796 (4.4%) than in men, N=2,465 (6.4%) (P< 0.001) (for follow-up information by cohort see Supplemental Table 2). Cumulative incidence curves with death as a competing risk are shown in Figure 1 and Supplemental Figure 1 (and by cohort in Supplemental Figure 2). The curves differed by sex. After the age of 50 years, AF incidence in men increased steeply, while in women this increase occurred after the age of 60 years. Both curves converged at the age of 90. AF incidence was very low before the age of 50.

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence curves and 95% confidence intervals for atrial fibrillation in women and men with death as a competing risk are shown. The numbers of individuals at risk are provided under the figure. Testing for the equality of the cumulative incidence curves produces a P value <0.001.

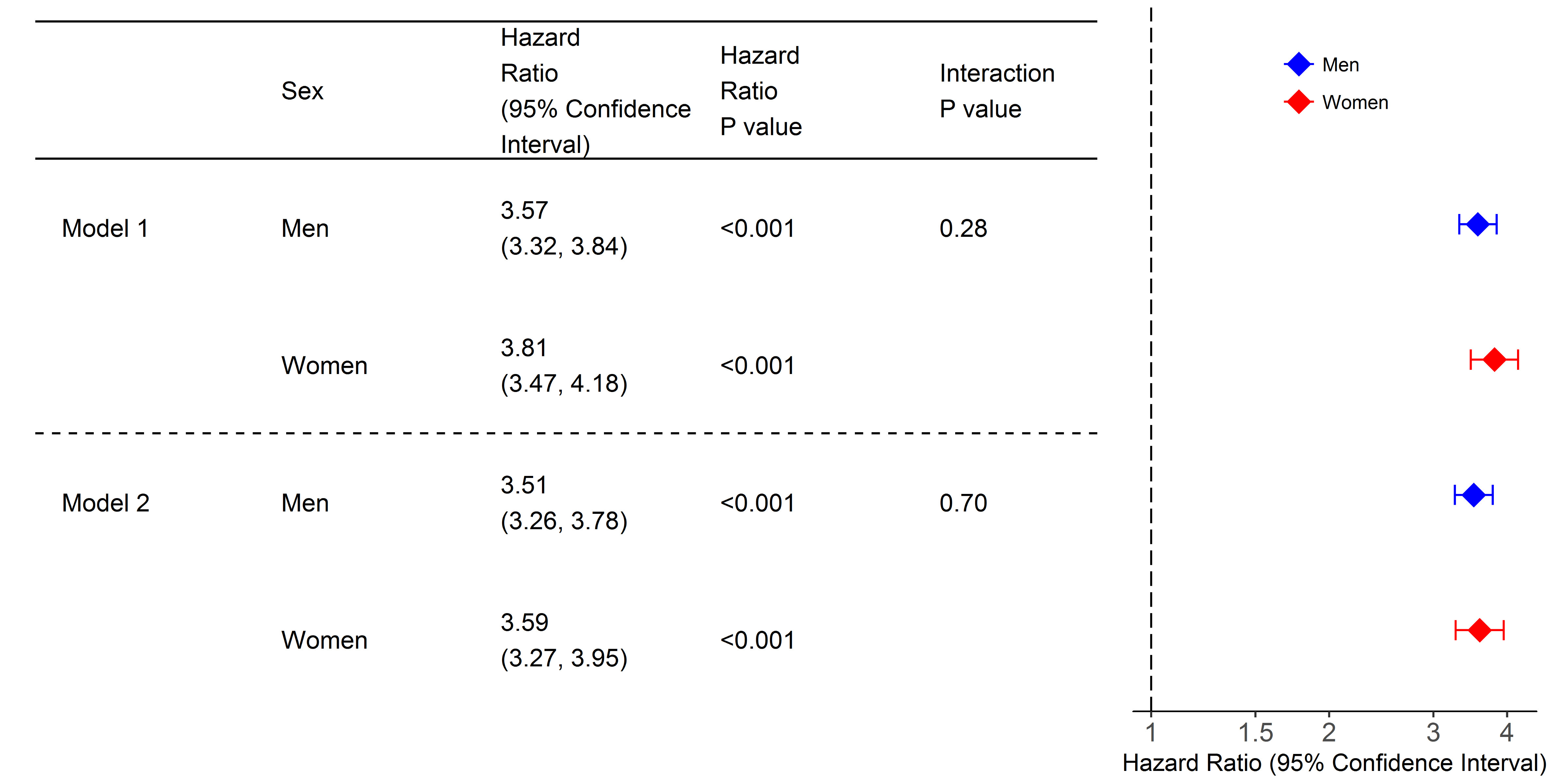

In age-adjusted and risk factor adjusted models, incident AF was associated with more than a 3.5-fold increased risk of death in both sexes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cox regression analyses for all-cause mortality with atrial fibrillation as time-dependent covariate, model 1. Model 2 is additionally adjusted for body mass index, systolic blood pressure, diabetes, daily smoking, antihypertensive medication, total cholesterol. The x-axis is shown on a log-scale.

Multivariable-adjusted HRs for AF by sex and the respective interaction P values are shown in Table 2. All cardiovascular risk factors (except for diabetes), history of stroke and myocardial infarction, and Nt-proBNP were associated with new onset AF in both sexes. Alcohol consumption and CRP were not associated with AF in women. We observed significant interactions by sex in the association between incident AF, BMI and total cholesterol. BMI was more strongly related to new onset AF in men, HR per standard deviation increase 1.31, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.25 to 1.38, compared to women, HR 1.18, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.23, with a RRR of 0.89, 95% CI 0.84 to 0.96. Total cholesterol was inversely associated with incident AF with a stronger risk reduction in women (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.90 versus 0.92, 95% CI 0.88 to 0.97 in men), RRR 0.93, 95% CI 0.87 to 0.99. The association persisted after accounting for cholesterol lowering medication in an exploratory analysis (Supplemental Table 3). Age-adjusted Cox regression models are provided in Supplemental Table 4. Additional interactions for Nt-proBNP and daily alcohol consumption lost statistical significance after multivariable adjustment.

Table 2.

Multivariable-adjusted atrial fibrillation hazard ratios by sex and interaction P values for atrial fibrillation risk factors in the overall sample.

| Variable | Interaction P value | Sex | Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

P value | Relative Risk Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 0.001 | Women | 1.18 (1.12, 1.23) | <0.001 | 0.89 (0.84, 0.96) |

| Men | 1.31 (1.25, 1.38) | <0.001 | |||

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 0.90 | Women | 1.09 (1.04, 1.15) | <0.001 | 1.00 (0.93, 1.07) |

| Men | 1.10 (1.05, 1.15) | <0.001 | |||

| Diabetes | 0.68 | Women | 1.15 (0.96, 1.38) | 0.14 | 1.05 (0.83, 1.34) |

| Men | 1.09 (0.93, 1.28) | 0.28 | |||

| Daily smoking | 0.27 | Women | 1.34 (1.17, 1.55) | <0.001 | 1.10 (0.93, 1.30) |

| Men | 1.22 (1.11, 1.35) | <0.001 | |||

| Antihypertensive medication | 0.077 | Women | 1.65 (1.47, 1.85) | <0.001 | 1.15 (0.99, 1.34) |

| Men | 1.43 (1.29, 1.59) | <0.001 | |||

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 0.023 | Women | 0.86 (0.81, 0.90) | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.87, 0.99) |

| Men | 0.92 (0.88, 0.97) | <0.001 | |||

| Alcohol consumption | 0.12 | Women | 1.07 (0.99, 1.15) | 0.072 | 0.93 (0.85, 1.02) |

| Men | 1.15 (1.10, 1.20) | <0.001 | |||

| History of stroke | 0.57 | Women | 1.42 (1.07, 1.88) | 0.014 | 1.11 (0.77, 1. 61) |

| Men | 1.28 (1.01, 1.62) | 0.042 | |||

| History of myocardial infarction | 0.55 | Women | 1.93 (1.55, 2.40) | <0.001 | 1.08 (0.84, 1.40) |

| Men | 1.78 (1.55, 2.05) | <0.001 | |||

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 0.40 | Women | 1.05 (0.96, 1.16) | 0.28 | 0.95 (0.84, 1.07) |

| Men | 1.11 (1.03, 1.12) | 0.006 | |||

| Nt-proBNP (ng/mL) | 0.16 | Women | 2.19 (1.95, 2.47) | <0.001 | 1.11 (0.96, 1.28) |

| Men | 1.98 (1.83, 2.14) | <0.001 |

Nt-proBNP stands for N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide.

The first six variables represent our base model, the others are separately added on top to the base model. All models include body mass index, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, daily smoking, diabetes, and antihypertensive medication. Biomarker information was available in a subgroup only (Supplemental Table 1).

Hazard ratios for continuous variables are for one standard deviation (SD) increase, body mass index: 4.67 kg/m², systolic blood pressure: 21 mm Hg, total cholesterol: 1.17 mmol/L, log(C-reactive protein, mg/L): 1.1, log(Nt-proBNP, ng/mL): 0.98, transformed alcohol consumption: 1.36. Standard deviations were computed using all observations regardless of sex.

C-reactive protein, Nt-proBNP and alcohol consumption were log-transformed. Since alcohol consumption can equal zero, one was added before applying the transformation.

In secondary analyses waist-to-hip ratio showed a stronger association with AF in men compared to women. The interaction did not reach statistical significance. Height revealed a stronger association with AF in women than in men, interaction P value <0.001 (Supplemental Table 5).

PARs for 5-year incident AF resulting from the classical risk factors are presented in Table 3. PARs of most classical risk factors were similar in both sexes. A higher PAR was observed for total cholesterol in women (PAR 8.6%, 95% CI 5.4 to 12.0) compared to men (PAR 3.8%, 95% CI 0.2 to 7.3). Alcohol consumption produced a higher PAR in men versus women in whom the PAR was very low with 0.2% in average volume drinking category II. The PAR of a history of myocardial infarction was higher in men (PAR 6.1%, 95% CI 4.2 to 8.2) compared to women (PAR 3.0%, 95% CI 1.5 to 4.5). Obesity accounted for a PAR of 13.3% in men and 14.4% in women. In total, the examined risk factors (BMI, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, daily smoking, diabetes, alcohol consumption, history of myocardial infarction and history of stroke) and cardiovascular diseases accounted for 41.9% and 46.0% of the PAR in women and in men, respectively.

Table 3.

Population attributable risk (%) for 5-year atrial fibrillation incidence by sex.

| Variable | PAR (95% Confidence Interval) Women |

PAR (95% Confidence Interval) Men |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass index 25 to <30 kg/m2 | 4.2 (0.1, 8.4) | 6.9 (2.0, 11.2) | |

| Body mass index ≥30kg/m2 | 14.4 (10.0, 19.0) | 13.3 (9.9, 17.0) | |

| Systolic blood pressure 120 to <140 mm Hg | 0.5 (-3.8, 4.4) | 4.7 (0.9, 8.8) | |

| Systolic blood pressure 140 to <160 mm Hg | 5.2 (-1.7, 10.7) | 5.0 (-0.1, 9.9) | |

| Systolic blood pressure ≥160 mm Hg | 9.0 (2.4, 14.2) | 8.7 (4.7, 13.1) | |

| Diabetes | 1.1 (-1.1, 3.4) | 0.5 (-1.4, 2.5) | |

| Daily smoking | 3.0 (1.2, 4.8) | 3.0 (0.8, 5.2) | |

| Total cholesterol <5.17 mmol/L | 8.6 (5.4, 12.0) | 3.8 (0.2, 7.3) | |

| Average drinking category II | 0.2 (-1.3, 2.0) | 2.1 (0.1, 4.2) | |

| Average drinking category III | 0.4 (-0.2, 1.3) | 1.6 (0.3, 3.1) | |

| History of myocardial infarction | 3.0 (1.5, 4.5) | 6.1 (4.2, 8.2) | |

| History of stroke | 1.1 (0.0, 2.5) | 0.5 (-0.5, 1.6) | |

|

| |||

| Total PAR (%) | 41.9 (29.4, 51.9) | 46.0 (38.2, 55.2) | |

The cause-specific Cox models used include body mass index, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, daily smoking, diabetes, alcohol consumption, history of myocardial infarction, history of stroke and antihypertensive medication. Age was used as the time scale. The models were stratified by sex and cohort.

Average drinking categories are based on pure alcohol intake: category II, for women 20-39.99 g/day, for men 40-59.99 g/day; category III, for women ≥40 g/day, for men ≥60 g/day.

PAR stands for population attributable risk.

Discussion

In a pooled analysis of community cohorts across Europe, the cumulative risk of developing AF was higher in men than in women over most of the lifespan but became similar at older age with a comparable lifetime risk. Incident AF was associated with more than a 3.5-fold increased mortality risk with no significant sex difference. Among the classical risk factors, higher BMI and lower total cholesterol were associated with a higher risk of AF in men than in women. PAR resulting from classical risk factors were largely comparable.

The age-dependency of AF is well known.7,19,20 We confirmed an increase in incidence of AF with age in women and men. Cumulative incidence was low in middle age. Women lagged about a decade behind men, but reached the cumulative incidence of men by the age of 90. Overall, a third of women and men were estimated to develop AF during their lifetime. A considerable lifetime risk of AF between one fifth and one fourth has been reported in studies with usually comparatively small numbers in the older age groups.20–6 With a broader age range, our data estimate the risk to be even higher. The risk of mortality related to AF onset as described earlier8,23 remains high. In both, women and men, AF was associated with more than a 3.5-fold increased risk of death with no evidence for a sex difference. Thus, AF poses a significant risk for premature mortality.

BMI and obesity are established risk factors for AF.7,24,25 Prior studies have found sex differences in the association of obesity with long-term incidence of AF. While no statistically significant interactions were reached in the Framingham Heart Study, the effect estimates showed a higher magnitude of association in men.26 In the Danish Diet, Cancer, and Health Study, obese women had a 2-fold higher risk of AF compared to men (HR of 2.35 in multivariable-adjusted analyses).27 An Australian study in more than 4,000 individuals reported a possible sex interaction of BMI with incident AF.28 Body fat distribution differs by sex and additional adiposity measures may need to be examined. For example, in a subsample of our cohorts, waist-to-hip ratio showed a stronger association with AF in men than in women but the interaction did not reach statistical significance. However, BMI has remained the strongest validated predictor of incident AF.29

Further secondary analyses in our sample revealed differential associations of height with AF in women and men. That, in part, may help to explain the observed sex differences for BMI. Increased height is related to higher risk of AF.30 This may be linked to a greater susceptibility to arrhythmia through larger cardiac dimensions and higher excitability of the conduction system.31,32 In our data the association appears to be stronger in women, which requires further examination to clarify possible mechanisms. Despite the role of height in our findings, BMI remains a central risk factor. Elevated BMI may be a sign of insufficient risk factor control.10 But the proportionality of weight gain and increased AF risk within short periods of follow-up33,34 and the close correlation of weight and weight fluctuations with AF patterns suggest a possible direct relationship with AF.35 Evidence suggests that the effects of obesity on cardiac structural remodeling and function differ by sex,36–38 which increases the predisposition to AF. Irrespective of the underlying mechanisms, BMI is a modifiable risk factor in AF.35,40 Its population attributable risk has significantly increased5 and has been reported to account for up to 18% of risk for incident AF in women.33 In our current sample the attributable risk was similar, about 20% if overweight and obese individuals were combined. Thus, BMI provides an opportunity for possible risk reduction in both sexes.

Women and men show well established differences in plasma lipid profiles.40 The counterintuitive inverse association of total cholesterol and other pro-atherogenic lipoproteins has been reported earlier.41,42 This observation has been explained by membrane stabilizing characteristics of cholesterol, although the exact pathophysiology remains unclear. Importantly, this inverse association was observed in both sexes in our study, with a borderline higher effect size in women.

The inflammatory biomarker CRP was associated with AF in men, but did not reach statistical significance in women. The HRs were relatively small as described in prior investigations.11 For the cardiac biomarker Nt-proBNP, an interaction by sex in age-adjusted models with a higher relative risk in women became non-significant after adjustment for clinical covariates. Sex and BMI are among the strongest correlates of Nt-proBNP concentrations. Female sex and obesity are correlated with higher natriuretic peptides.43,44 Thus, confounding, the small sample size with available information on Nt-proBNP or more complex interactions may explain the observations, which need to be elucidated in further studies.

Sex differences for risk factor associations have consistently been reported for diabetes and smoking in relation to coronary heart disease and stroke, with a higher relative risk of developing disease in women.45–47 In contrast to coronary heart disease and stroke, diabetes was not associated with incident AF in our cohorts and no interaction by sex was observed. Smoking usually carries a higher risk for cardiovascular disease in women.45,46 We could not extend this knowledge towards AF where the association appeared to be similar in both sexes. Differences in sex for prior cardiovascular disease prevalence are well established major risk factors for incident AF.48,49 Our study indicates that previous myocardial infarction or stroke are associated with similar risk of developing AF in women and men and are therefore comparable risk indicators in both sexes.

Limitations and strengths

Our data are restricted to epidemiological observations that cannot reveal potential mechanisms explaining the differential associations by sex. Data on the pathophysiological pathways potentially underlying sex-specific differences are needed. Furthermore, our results on cardiovascular risk factors are not sufficient to examine potential sex disparities. Unfortunately, baseline ECGs were not available systematically in all cohorts, which may have led to an underdiagnosis of AF and introduced bias. Follow-up information on AF derived from hospital discharge data, including data on ambulatory visits to specialized hospitals may lead to misclassification of AF cases, in particular intermittent AF. This possible misclassification may have led to a lower incidence and a weakening of the associations of classical risk factors with incident AF and mortality. In the past, the specificity of administrative registry data has been proven to be good with limitations in sensitivity.50,51 In addition, biomarker information was only available in a subgroup of the study sample. The relating results are hypothesis-generating and have thus to be interpreted with caution.

The strength of the study is the population-based and longitudinal study design. Furthermore, we used harmonized data on classical cardiovascular risk factors and biomarker measurements in large studies with long-term follow-up information with sufficient power to examine sex interactions.

In conclusion, our data provide evidence that differences in AF incidence observed by sex may be explained by the sex-specific distribution of risk factors and by differential associations of classical risk factors. A substantial proportion of the AF burden can be explained by classical cardiovascular disease risk factors in both sexes. While blood pressure, smoking, alcohol consumption, Nt-proBNP, and prevalent cardiovascular disease are largely similar predictors of incident AF in both sexes, total cholesterol concentrations may show sex differences. A higher BMI and obesity are stronger risk factors for the development of AF in men and require better awareness and targeted intervention.

Understanding the sex differences in AF risk and risk factors is essential for developing long-term preventive measures to reduce mortality, public health burden and healthcare costs related to AF in both women and men.

Supplemental Material

Clinical Perspective.

What is new?

In European community cohorts, life-time risk of atrial fibrillation (AF) was more than 24% by the age of ninety in both sexes.

Men developed AF a decade earlier.

Interim AF was associated with more than a 3.5-fold increased mortality risk.

Among the classical risk factors, body mass index (BMI) explained the largest proportion of AF risk.

Sex interactions were seen for risk associations of BMI and total cholesterol.

What are the clinical implications?

AF is a frequent disease and is related to high mortality.

AF risk factors are similar in both sexes.

Observed sex differences for BMI and total cholesterol need to be evaluated for their relevance in sex-specific prevention strategies.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and the staff of the cohorts for their continuing dedication and efforts.

Sources of Funding

The BiomarCaRE Project is funded by the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement No. HEALTH-F2-2011-278913. The activities of the MORGAM Data Center have been sustained by recent funding from European Union FP 7 project CHANCES (HEALTH-F3-2010-242244). A part of the biomarker determinations in the population cohorts was funded by the Medical Research Council London (G0601463, identification No. 80983: Biomarkers in the MORGAM Populations).

The FINRISK surveys were mainly funded by budgetary funds of THL. Additional funding has been obtained from numerous non-profit foundations. Dr Salomaa (PI) has been supported by the Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research and the Academy of Finland (grant number 139635).

The DanMONICA cohorts at the Research Center for Prevention and Health were established over a period of ten years and have been funded by numerous sources which have been acknowledged, where appropriate, in the original articles.

The Moli-sani was partially supported by research grants from Pfizer Foundation (Rome, Italy), the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MIUR, Rome, Italy)–Programma Triennale di Ricerca, Decreto n.1588 and Instrumentation Laboratory (Milan, Italy).

The Northern Sweden MONICA project was supported by Norrbotten and Västerbotten County Councils. Dr Söderberg has been supported by the Swedish Heart–Lung Foundation (grant numbers 20140799, 20120631, 20100635), the County Council of Västerbotten (ALF, VLL-548791) and Umeå University.

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 648131), German Ministry of Research and Education (BMBF 01ZX1408A), and German Research Foundation Emmy Noether Programme (SCHN 1149/3-1) (to Dr Schnabel). Additional funding was provided to Dr Schnabel (81Z1710103) and Dr Zeller (81Z1710101) by the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK).

Abbreviations

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- FU

follow-up

- HR

hazard ratio

- Nt-proBNP

N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide

- PAR

population attributable risk

- RRR

relative risk ratio

- SD

standard deviation

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Reference List

- 1.Stefansdottir H, Aspelund T, Gudnason V, Arnar DO. Trends in the incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation in Iceland and future projections. Europace. 2011;13:1110–1117. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schnabel RB, Wilde S, Wild PS, Munzel T, Blankenberg S. Atrial fibrillation: its prevalence and risk factor profile in the German general population. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109:293–299. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2012.0293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brouwers FP, de Boer RA, van der Harst P, Voors AA, Gansevoort RT, Bakker SJ, Hillege HL, van Veldhuisen DJ, van Gilst WH. Incidence and epidemiology of new onset heart failure with preserved vs. reduced ejection fraction in a community-based cohort: 11-year follow-up of PREVEND. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:1424–1431. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lip GY, Laroche C, Boriani G, Cimaglia P, Dan GA, Santini M, Kalarus Z, Rasmussen LH, Popescu MI, Tica O, Hellum CF, et al. Sex-related differences in presentation, treatment, and outcome of patients with atrial fibrillation in Europe: a report from the Euro Observational Research Programme Pilot survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Europace. 2015;17:24–31. doi: 10.1093/europace/euu155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schnabel RB, Yin X, Gona P, Larson MG, Beiser AS, McManus DD, Newton-Cheh C, Lubitz SA, Magnani JW, Ellinor PT, Seshadri S, et al. 50 year trends in atrial fibrillation prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and mortality in the Framingham Heart Study: a cohort study. Lancet. 2015;386:154–162. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61774-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heeringa J, van der Kuip DA, Hofman A, Kors JA, van HG, Stricker BH, Stijnen T, Lip GY, Witteman JC. Prevalence, incidence and lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation: the Rotterdam study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:949–953. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vermond RA, Geelhoed B, Verweij N, Tieleman RG, van der Harst P, Hillege HL, van Gilst WH, Van Gelder IC, Rienstra M. Incidence of Atrial Fibrillation and Relationship With Cardiovascular Events, Heart Failure, and Mortality: A Community-Based Study From the Netherlands. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1000–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.06.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB, Levy D. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1998;98:946–952. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.10.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hart RG, Pearce LA, McBride R, Rothbart RM, Asinger RW. Factors associated with ischemic stroke during aspirin therapy in atrial fibrillation: analysis of 2012 participants in the SPAF I-III clinical trials. The Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation (SPAF) Investigators. Stroke. 1999;30:1223–1229. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.6.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huxley RR, Lopez FL, Folsom AR, Agarwal SK, Loehr LR, Soliman EZ, Maclehose R, Konety S, Alonso A. Absolute and attributable risks of atrial fibrillation in relation to optimal and borderline risk factors: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Circulation. 2011;123:1501–1508. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinner MF, Stepas KA, Moser CB, Krijthe BP, Aspelund T, Sotoodehnia N, Fontes JD, Janssens AC, Kronmal RA, Magnani JW, Witteman JC, et al. B-type natriuretic peptide and C-reactive protein in the prediction of atrial fibrillation risk: the CHARGE-AF Consortium of community-based cohort studies. Europace. 2014;16:1426–1433. doi: 10.1093/europace/euu175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalogeropoulos A, Georgiopoulou V, Psaty BM, Rodondi N, Smith AL, Harrison DG, Liu Y, Hoffmann U, Bauer DC, Newman AB, Kritchevsky SB, et al. Inflammatory markers and incident heart failure risk in older adults: the Health ABC (Health, Aging, and Body Composition) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2129–2137. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeller T, Hughes M, Tuovinen T, Schillert A, Conrads-Frank A, Ruijter H, Schnabel RB, Kee F, Salomaa V, Siebert U, Thorand B, et al. BiomarCaRE: rationale and design of the European BiomarCaRE project including 300,000 participants from 13 European countries. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29:777–790. doi: 10.1007/s10654-014-9952-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans A, Salomaa V, Kulathinal S, Asplund K, Cambien F, Ferrario M, Perola M, Peltonen L, Shields D, Tunstall-Pedoe H, Kuulasmaa K. MORGAM (an international pooling of cardiovascular cohorts) Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:21–27. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alonso A, Krijthe BP, Aspelund T, Stepas KA, Pencina MJ, Moser CB, Sinner MF, Sotoodehnia N, Fontes JD, Janssens AC, Kronmal RA, et al. Simple Risk Model Predicts Incidence of Atrial Fibrillation in a Racially and Geographically Diverse Population: the CHARGE-AF Consortium. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000102. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blankenberg S, Zeller T, Saarela O, Havulinna AS, Kee F, Tunstall-Pedoe H, Kuulasmaa K, Yarnell J, Schnabel RB, Wild PS, Munzel TF, et al. Contribution of 30 biomarkers to 10-year cardiovascular risk estimation in 2 population cohorts: the MONICA, risk, genetics, archiving, and monograph (MORGAM) biomarker project. Circulation. 2010;121:2388–2397. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.901413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aalen OO, Johansen S. An empirical transition matrix for non-homogeneous Markov chains based on censored observations. Scand J Statist. 1978;5:141–150. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korn EL, Graubard BI, Midthune D. Time-to-event analysis of longitudinal follow-up of a survey: choice of the time-scale. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:72–80. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chugh SS, Havmoeller R, Narayanan K, Singh D, Rienstra M, Benjamin EJ, Gillum RF, Kim YH, McAnulty JH, Jr, Zheng ZJ, Forouzanfar MH, et al. Worldwide epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: a Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Circulation. 2014;129:837–847. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandalenakis Z, Von KL, Eriksson H, Dellborg M, Caidahl K, Welin L, Rosengren A, Hansson PO. The risk of atrial fibrillation in the general male population: a lifetime follow-up of 50-year-old men. Europace. 2015;17:1018–1022. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lloyd-Jones DM, Wang TJ, Leip EP, Larson MG, Levy D, Vasan RS, D'Agostino RB, Massaro JM, Beiser A, Wolf PA, Benjamin EJ. Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2004;110:1042–1046. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140263.20897.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo Y, Tian Y, Wang H, Si Q, Wang Y, Lip GY. Prevalence, incidence, and lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation in China: new insights into the global burden of atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2015;147:109–119. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conen D, Chae CU, Glynn RJ, Tedrow UB, Everett BM, Buring JE, Albert CM. Risk of death and cardiovascular events in initially healthy women with new-onset atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2011;305:2080–2087. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wanahita N, Messerli FH, Bangalore S, Gami AS, Somers VK, Steinberg JS. Atrial fibrillation and obesity--results of a meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2008;155:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nyrnes A, Mathiesen EB, Njolstad I, Wilsgaard T, Lochen ML. Palpitations are predictive of future atrial fibrillation. An 11-year follow-up of 22,815 men and women: the Tromso Study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2013;20:729–736. doi: 10.1177/2047487312446562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang TJ, Parise H, Levy D, D'Agostino RB, Sr, Wolf PA, Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ. Obesity and the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2004;292:2471–2477. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.20.2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frost L, Hune LJ, Vestergaard P. Overweight and obesity as risk factors for atrial fibrillation or flutter: the Danish Diet, Cancer, and Health Study. Am J Med. 2005;118:489–495. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knuiman M, Briffa T, Divitini M, Chew D, Eikelboom J, McQuillan B, Hung J. A cohort study examination of established and emerging risk factors for atrial fibrillation: the Busselton Health Study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29:181–190. doi: 10.1007/s10654-013-9875-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aronis KN, Wang N, Phillips CL, Benjamin EJ, Marcus GM, Newman AB, Rodondi N, Satterfield S, Harris TB, Magnani JW. Associations of obesity and body fat distribution with incident atrial fibrillation in the biracial health aging and body composition cohort of older adults. Am Heart J. 2015;170:498–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kofler T, Theriault S, Bossard M, Aeschbacher S, Bernet S, Krisai P, Blum S, Risch M, Risch L, Albert CM, Pare G, et al. Relationships of Measured and Genetically Determined Height With the Cardiac Conduction System in Healthy Adults. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2017;10:e004735. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.116.004735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abhayaratna WP, Seward JB, Appleton CP, Douglas PS, Oh JK, Tajik AJ, Tsang TS. Left atrial size: physiologic determinants and clinical applications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2357–2363. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chun KJ, Hwang JK, Park SJ, On YK, Kim JS, Park KM. Electrical PR Interval Variation Predicts New Occurrence of Atrial Fibrillation in Patients With Frequent Premature Atrial Contractions. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3249. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tedrow UB, Conen D, Ridker PM, Cook NR, Koplan BA, Manson JE, Buring JE, Albert CM. The long- and short-term impact of elevated body mass index on the risk of new atrial fibrillation the WHS (women's health study) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2319–2327. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hatem SN, Sanders P. Epicardial adipose tissue and atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;102:205–213. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pathak RK, Middeldorp ME, Lau DH, Mehta AB, Mahajan R, Twomey D, Alasady M, Hanley L, Antic NA, McEvoy RD, Kalman JM, et al. Aggressive risk factor reduction study for atrial fibrillation and implications for the outcome of ablation: the ARREST-AF cohort study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2222–2231. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuch B, Muscholl M, Luchner A, Doring A, Riegger GA, Schunkert H, Hense HW. Gender specific differences in left ventricular adaptation to obesity and hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 1998;12:685–691. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piro M, Della BR, Abbate A, Biasucci LM, Crea F. Sex-related differences in myocardial remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1057–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de SG, Devereux RB, Chinali M, Roman MJ, Barac A, Panza JA, Lee ET, Howard BV. Sex differences in obesity-related changes in left ventricular morphology: the Strong Heart Study. J Hypertens. 2011;29:1431–1438. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328347a093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abed HS, Wittert GA, Leong DP, Shirazi MG, Bahrami B, Middeldorp ME, Lorimer MF, Lau DH, Antic NA, Brooks AG, Abhayaratna WP, et al. Effect of weight reduction and cardiometabolic risk factor management on symptom burden and severity in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2050–2060. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peters SA, Singhateh Y, Mackay D, Huxley RR, Woodward M. Total cholesterol as a risk factor for coronary heart disease and stroke in women compared with men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2016;248:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mora S, Akinkuolie AO, Sandhu RK, Conen D, Albert CM. Paradoxical association of lipoprotein measures with incident atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014;7:612–619. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.001378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lopez FL, Agarwal SK, Maclehose RF, Soliman EZ, Sharrett AR, Huxley RR, Konety S, Ballantyne CM, Alonso A. Blood lipid levels, lipid-lowering medications, and the incidence of atrial fibrillation: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5:155–162. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.966804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, Leip EP, Benjamin EJ, Wilson PW, Sutherland P, Omland T, Vasan RS. Impact of age and sex on plasma natriuretic peptide levels in healthy adults. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:254–258. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02464-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, Leip EP, Wilson PW, Vasan RS. Impact of obesity on plasma natriuretic peptide levels. Circulation. 2004;109:594–600. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000112582.16683.EA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huxley R, Barzi F, Woodward M. Excess risk of fatal coronary heart disease associated with diabetes in men and women: meta-analysis of 37 prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2006;332:73–78. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38678.389583.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peters SA, Huxley RR, Woodward M. Diabetes as a risk factor for stroke in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 64 cohorts, including 775,385 individuals and 12,539 strokes. Lancet. 2014;383:1973–1980. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huxley RR, Woodward M. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for coronary heart disease in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Lancet. 2011;378:1297–1305. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60781-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ball J, Carrington MJ, Wood KA, Stewart S. Women versus men with chronic atrial fibrillation: insights from the Standard versus Atrial Fibrillation spEcific managemenT studY (SAFETY) PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e65795. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Potpara TS, Marinkovic JM, Polovina MM, Stankovic GR, Seferovic PM, Ostojic MC, Lip GY. Gender-related differences in presentation, treatment and long-term outcome in patients with first-diagnosed atrial fibrillation and structurally normal heart: the Belgrade atrial fibrillation study. Int J Cardiol. 2012;161:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bengtson LG, Kucharska-Newton A, Wruck LM, Loehr LR, Folsom AR, Chen LY, Rosamond WD, Duval S, Lutsey PL, Stearns SC, Sueta C, et al. Comparable ascertainment of newly-diagnosed atrial fibrillation using active cohort follow-up versus surveillance of centers for medicare and medicaid services in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e94321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mikkelsen L, Phillips DE, AbouZahr C, Setel PW, de SD, Lozano R, Lopez AD. A global assessment of civil registration and vital statistics systems: monitoring data quality and progress. Lancet. 2015;386:1395–1406. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.