Abstract

Integrin-targeting peptide RGDfK-labeled gold nanorods (GNR) seek to improve hyperthermia targeted to solid tumors by exploiting the known up-regulation of integrin αvβ3 cell membrane proteins on solid tumor vasculature surfaces. Tumor binding specificity might be expected since surrounding tissues and endothelial cells have limited numbers of these receptors. However, RGD peptide binding to many proteins is promiscuous, with known affinity to several families of cell integrin receptors, and also possible binding to platelets after intravenous infusion via a different integrin receptor, αIIbβ3, on platelets. Binding of RGDfK-targeted GNR could considerably impact platelet function, ultimately leading to increased risk of bleeding or thrombosis depending on the degree of interaction. We sought to determine if RGDfK-labeled GNR could interact with platelets and alter platelet function. Targeted and untargeted nanorods exhibited little interaction with resting platelets in platelet rich plasma (PRP) preparations. However, upon platelet activation, peptide-targeted nanorods bound actively to platelets. Addition of RGDfK-GNR to unactivated platelets had little effect on markers of platelet activation, indicating that RGDfK-nanorods were incapable of inducing platelet activation. We next tested whether activated platelet function was altered in the presence of peptide-targeted nanorods. Platelet aggregation in whole blood and PRP in the presence of targeted nanorods had no significant effect on platelet aggregation. These data suggest that RGDfK-GNR alone have little impact on platelet function in plasma. However, nonspecific nanorod binding may occur in vascular beds where activated platelets are normally cleared, such as the spleen and liver, producing a possible toxicity risk for these nanomaterials.

Keywords: nanoparticles, coagulation, peptide ligand, blood clot, activation, integrin

INTRODUCTION

The vascular bed of solid tumor tissues is distinguished from that of normal tissues by the presence of over-expressed surface markers on vascular endothelium.1,2 Targeting of cancer treatments toward the angiogenic endothelium of solid tumors has frequently used monocyclic peptide RGDfK to target the cell membrane integrin of interest (αvβ3) found in the neo-vasculature of developing tumors.3–6 Despite integrin peptide targeting.7,8 this approach often leads to dose deposition at nontarget sites for RGD-labeled soluble polymers,9,10 particles, 11–13 and other bioactive compounds.14–17 In vitro affinities for RGD and RGDfK peptide ligands in serum-free media with endothelial cell lines are 12.22 × 106 M−1 and 6.33 × 106 M−1 (Kd=818 and 158 nM), respectively.18 In vivo, the integrin affinity constant for 99mTc-RGD was reported to be comparable (7 × 106M−1) in both human renal adenocarcinoma and human colon cancer cell line-based murine ectopic tumor models. Nonetheless, tumor accumulation of 99mTc-labeled RGD versus RGE controls exhibited no statistical differences, possibly due to limited numbers of αVβ3 integrin receptors per tumor cell and the modest RGD binding affinity, limiting in vivo RGD-based targeting.19

The αvβ3 integrin receptor targeted by RGD is also found on platelets20 and as a receptor for phagocytosis on macrophages21 and dendritic cells.22 The binding promiscuity of the RGDfK peptide moiety allows it to not only target the αvβ3 integrin, but also other integrins in the same family, such as αIIbβ3,23,24 an integrin expressed on platelets. 25,26 Platelet αIIbβ3 integrin activation is the final step in platelet aggregation pathway, regardless of the initial activating stimulus. Recent studies of the biodistribution of intravenously administered RGDfK-targeted drug carriers indicate more rapid clearance and frequently less tumor accumulation than their untargeted counterparts.10,27 One hypothesized mechanism producing this RGD-mediated particle-targeting failure and gold nanorods (GNRs) rapid clearance is promiscuous RGD-mediated platelet binding and possible aggregation response during GNR intravenous infusion, attributed to the high concentration and abundant availability of alternative competing platelet integrin targets present in blood.

Platelets circulate in the blood at concentrations of 150 × 109/L to 400 × 109/L with a half-life of around ten days.28 Platelets are activated by many different agonists, and upon activation provide a high concentration of exposed integrins on their activated membranes. These integrins are known to bind many different peptides29 and may bind RGDfK off-target to reduce the fractional dosage of RGDfK-guided therapy reaching its intended target by binding integrin αvβ3 in the tumor vasculature. In addition, any interference with the diverse platelet surface integrins by RGDfK-targeted therapies may have unintended hemostatic consequences by affecting the patient’s ability to activate platelets normally, form stable clots and prevent bleeding. Despite the prevalence of RGD-targeted tumor studies using intravenously administered agents (liposomes, polymers, particles), few studies detail RGD peptide binding and possible activation of platelets. We therefore have examined how RGDfK-labeled GNR might alter platelet function ex vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

GNRs synthesis

GNRs were prepared as described previously.27 Briefly, GNRs were fabricated by gold salt reduction in hexadecyltri-methylammonium bromide (CTAB) to exhibit a characteristic surface plasmon resonance peak for GNRs between 800–810 nm. After successive washing and centrifugation in deionized water to remove excess CTAB, GNRs were stored at 4°C in water until coated with thiolated polyethylene glycol (PEG 5000 MW, Creative PEGWorks) bearing terminal cyclic peptides RGDfK or control RGEfK (New England Peptide, Inc.). PEG-peptide conjugates were prepared as previously described27. GNR PEGylation was performed by addition of either thiolated RGDfK-PEG conjugates or thiolated RGEfK conjugates (100 μM) for 2 hr at room temperature under stirring. The PEGylated GNRs were then thoroughly dialyzed (3.5k MWCO, Spectrum Labs), sterile filtered, concentrated by centrifugation and stored at 4°C for a maximum of two months. Resulting GNR size and shape were determined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and GNR peptide content was found by amino acid analysis (University of Utah Core Research Facilities, Salt Lake City). GNRs were diluted to optical density of 1 or 10 at 810 nm, which is the equivalent of 10 or 100 μg/mL, for use in all studies.

Whole blood collection and platelet preparation

Human peripheral venous blood from healthy, medication-free adult subjects (n=10–15 different donors) was drawn into acid-citrate-dextrose (1.4 mL of ACD/8.6 mL of blood) through a standard venipuncture technique and used immediately upon collection. Platelets were isolated from whole blood and purified platelets re-suspended in M199 medium (Lonza, Walkersville, USA) (1 × 108 platelets/mL, final) as previously described30–33 with minimal leukocyte contamination. 34–37 In some cases, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was obtained from whole blood after the first centrifugation step. PRP and purified platelet preparations were used within 4 h.

Flow cytometry

Platelet activation was evaluated in isolated platelet and whole blood systems. Isolated platelets treated with RGDfK-PEG- or RGEfK-PEG-bearing GNRs for indicated times were stained for P-selectin (CD62P, a marker of platelet alpha granule release) using phycoerythrin (PE) (BD Biosciences, San Jose, USA) or using PAC-1 (a marker of αIIbβ3 activation) using dye-labeled Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (BD Biosciences, San Jose, USA). Platelets were then analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACScan (BD Biosciences, USA). Whole blood was simultaneously analogously stained and stimulated with either RGDfK-PEG- or RGEfK-PEG-bearing GNRs for 15 min. In addition to CD62P and PAC-1, platelets were also identified using FITC or PE anti-human CD41a (BD Biosciences, USA) and analyzed by flow cytometry as above. Thrombin (0.1 U/mL, final) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) or Ser-Phe-Leu-Leu-Arg-Asn-Pro-Lys-Tyr-Glu-Pro-Phe (TRAP,10 μM, final) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) activation was used as a positive control in washed platelets or whole blood, respectively. To assess if fibrinogen was still capable of binding platelets in the presence of RGDfK- or RGEfK-labeled GNRs, Alexa-fluor 488-labeled fibrinogen (Invitrogen, USA) (100 μg/mL, final) was added to platelets for 15 min and binding measured compared to platelets incubated with fibrinogen alone.

Dark field microscopy

Isolated platelets treated for indicated times with RGDfK- or RGEfK-coated GNRs and in some cases, activated with thrombin 0.1 U/mL (final concentration). In some experiments untargeted GNRs were used. No difference in untargeted or RGEfK-targeted GNRs was observed. Samples were then fixed and mounted to slides with mounting medium. Slides were then imaged as previously described27 with an Olympus BX41 microscope coupled to the CytoViva 150 Ultra Resolution Imaging (URI) System (CytoViva Inc., Auburn, USA) using a 100× oil objective.38 A DAGE XLM (DAGE-MTI, Michigan City, USA) digital camera and software were used to capture and store images.

Platelet aggregometry

RGDfK- or RGEfK-labeled GNRs were added to citrated human whole blood at 10 μg/mL final or PRP at 1 μg/mL final and platelet aggregation in whole blood was then measured by impedance in a whole blood aggregometer (Chronolog Model 490, Havertown, PA, USA) or by turbidity in a light transmission aggregometer (Chronolog Model 490) immediately after addition of type 1 fibril collagen agonist (2.5 μg/mL final, Chronolog).

Statistical analysis

Data are representative as the mean±standard error of the mean. Significant was determined by Student’s t test or by ANOVA. When significance was reached for multiple comparisons, a Tukey’s post-hoc analysis was used. Significance was determined at a p ≤ 0.05. All experiments were performed a minimum of three times (technical replicates).

RESULTS

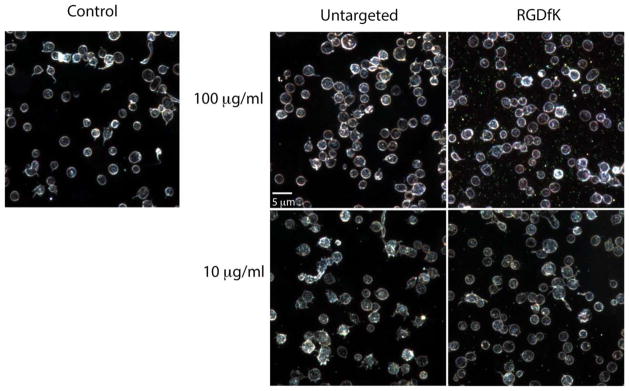

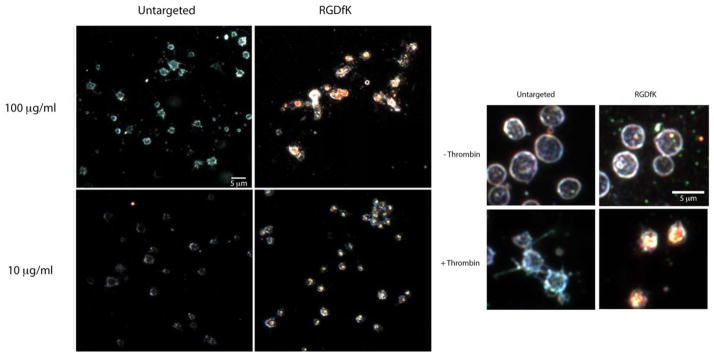

Because GNRs intrinsically scatter light as metallic nanoparticles, GNR binding to the platelets was qualitatively visualized by high-resolution dark field microscopy (Figs. 1 and 2). Captured images show that targeted (RGDfK) GNRs associated with platelets only after activation with thrombin (Figs. 1 and 2). Untargeted GNRs demonstrated no significant or detectable platelet associations. Similar findings were observed with RGEfK GNRs (data not shown). This suggested the direct involvement of αIIbβ3, an RGDfK-binding integrin, in platelet-GNR associations.

FIGURE 1.

RGDfK-labeled GNRs dβo not bind unactivated platelets. Purified platelets were pre-incubated with the indicated concentration of RGDfK-labeled GNRs or untargeted GNRs and then imaged using dark field microscopy (intrinsic GNR light scattering detected). The platelets were then imaged using dark field microscopy. Experiments were performed at least three times.

FIGURE 2.

RGDfK-labeled GNRs bind activated platelets. Purified platelets were stimulated 0.1 U/mL thrombin in the presence of the indicated concentration of RGDfK-labeled GNRs or untargeted GNRs. Inset shows a higher magnification of unstimulated and thrombin stimulated platelets in the presence of 100 μg/mL RGDfK GNR. The platelets were then imaged using dark field microscopy. Experiments were performed at least three times.

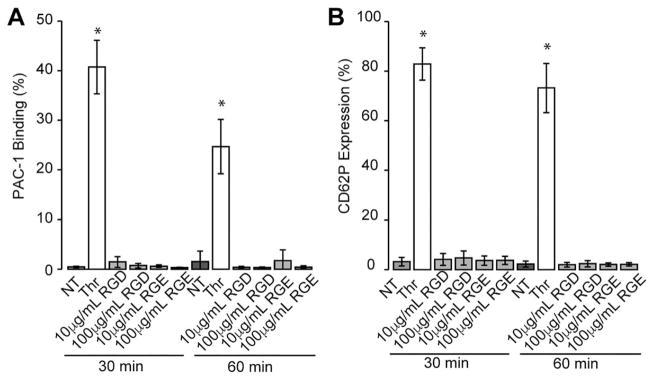

To determine if different GNR dosages activate human platelets in a time-dependent manner, purified platelets were incubated with GNRs for varying times and expression of P-selectin (CD62P), a marker of alpha granule release, and PAC-1 binding, a marker of αIIbβ3 activation, were assessed via flow cytometry. Activation of platelets with thrombin demonstrated significant expression of P-selectin and PAC-1 binding, indicating platelets were capable of being activated as a positive control. However, no significant platelet activation with these markers was observed using either the RGDfK or RGEfK-GNRs at any time point or GNR dosage (Fig. 3). GNRs alone did not induce platelet activation (Supporting Information Fig. S1).

FIGURE 3.

Purified platelets in PRP are not activated by RGDfK-GNRs in a time-dependent manner. RGDfK-labeled GNRs at 10 μg/mL or 100 μg/mL were added to purified platelets for 30 minutes or 1 hour. After these incubation periods, platelets were stained with CD41 antibody, and activation was assessed by flow cytometry for CD62P expression and conformational changes in integrin αIIbβ3 through PAC-1 binding. Positive staining was confirmed by activating platelets with the PAR1 agonist, thrombin (0.1 U/mL, final) compared to nontreated purified platelets (NT). Averages± standard deviations are shown from an n ≥ 3. * indicates significantly different compared to other conditions tested (p>0.05).

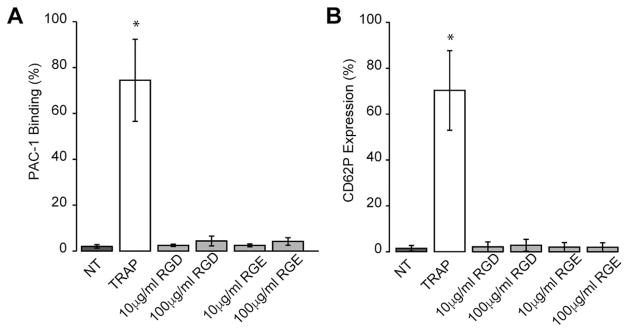

Since GNRs also interact with other cells in the blood expressing integrin receptors, we next assessed if GNRs were capable of activating platelets in more complex milieu. Whole blood was isolated and incubated with different concentrations of RGDfK- or RGEfK-labeled GNRs and platelet activation markers were assessed by flow cytometry. Similar to our purified platelet PRP results, platelets were activated when incubated with a known platelet agonist TRAP but showed no activation when incubated with either GNR or GNRs alone (Fig. 4 and Supporting Information Fig. S2).

FIGURE 4.

RGDfK-labeled GNRs do not induce platelet activation in whole blood. RGDfK-labeled GNRs at 10 μg/mL or 100 μg/mL were added to healthy human citrated blood and incubated for 30 min. After 30 min, platelets were stained with a CD41 antibody and activation was assessed by flow cytometry for CD62P expression and conformational changes in integrin αIIbβ3 (PAC-1 binding). Positive staining was confirmed by activating platelets with the PAR1 agonist, TRAP (10 μM, final) compared to nontreated whole blood (NT). Averages±standard deviations are shown from an n ≥ 3. * indicates significantly different compared to other conditions tested (p>0.05).

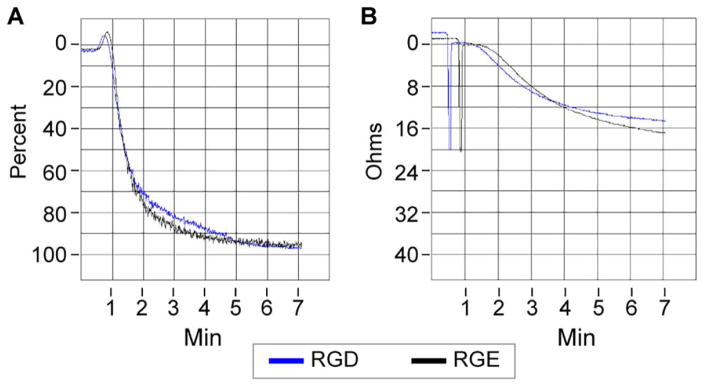

These initial data suggest that GNRs are unable to activate quiescent platelets and only interact with platelets when pre-activated by specific platelet agonists (for example, thrombin, collagen). Since activated platelets play a substantial role in preventing bleeding through integrin-dependent mechanisms, 39 RGDfK-labeled GNRs could interfere with platelet functions and increase risks for coagulopathies or bleeding. To test if platelet function is compromised in the presence of RGDfK-GNRs, platelet aggregation was assessed. Platelet aggregation depends on fibrinogen, a RGD-containing protein,40–42 binding to αIIbβ3; therefore, we first determined if fibrinogen binding to platelets was altered in the presence of RGDfK-labeled GNRs. Labeled fibrinogen bound to platelets and in an activated-dependent manner, and was not competed off by addition of RGDfK-labeled GNRs (data not shown). Light transmission aggregometry confirmed fibrinogen binding results by demonstrating no significant differences between platelets left untreated compared to RGDfK-GNRs or RGEfK GNRs [Fig. 5(A) and Supporting Information Fig. S3]. In addition, whole blood platelet aggregation showed no significant changes in the presence of RGDfK-GNRs [Fig. 5(B) and Supporting Information Fig. S4]. GNRs alone had no effect on platelet aggregation (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

RGDfK-labeled GNRs do not alter platelet aggregation. Purified platelets in PRP were left untreated or treated with 1 μg/mL RGDfK- or RGEfK-labeled (control) GNRs. The platelets were then stimulated with 2.5 μg/mL collagen and platelet aggregation was monitored using Chrono-log platelet aggregator. A representative tracing for purified platelet PRP treated with RGDfK (blue) and RGEfK control (black) are shown above (A). Citrated whole blood was left untreated or treated with 10 μg/mL RGDfK or RGEfK-labeled GNRs. Whole blood was then stimulated with 10 μg/mL collagen and platelet aggregation was monitored using Chrono-log whole blood aggregometry. A representative tracing for whole blood treated with RGDfK (blue) and RGEfK (black) are shown above (B). N>3 for each condition examined.

DISCUSSION

Diagnostic, biomedical, and clinical applications for gold nanoparticles are diverse and increasing, central to new optical imaging-based contrast agents, delivery vehicles for drugs and infused media for photothermal therapy.43–47 Targeted approaches to elicit selective and specific binding and tissue biodistributions using specific ligands conjugated to gold nanoparticle surfaces are reported to increase their localization to specific tissues13,48,49 although substantial off-target accumulation in filtration organs (that is, RES/MPS system comprising liver, spleen, kidneys, lungs) is consistently reported. In targeting nanoparticles in vitro and in vivo, significant attention has been paid to the αvβ3 integrins, commonly targeted through the well-known cell adhesion peptide, Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD), and its increasingly diverse related peptide analogs.50,51 Interestingly, αvβ3 is highly expressed on endothelial cells lining tumor and tumor cells but poorly expressed in resting endothelial cells.52,53 Thus, selectively targeting the αvβ3 integrin with anti-tumor drugs or thermal stress is thought to provide an opportunity to deliver agents and destroy tumor vessels while leaving healthy tissue intact. However, previous efforts have had only moderate success in targeting such therapies using RGD ligands to these tumor-specific receptors.9–17 More specifically, a prior report describing intravenous infusion of the same RGDfK-labeled GNRs used here to ectopic solid murine tumor models showed that the majority of the GNRs were sequestered by the liver and spleen, with little targeting specificity seen toward the tumor.10,27

Given the significant high specific surface areas for GNRs (~100 m2/g) and their stochastic encounters in blood after intravenous introduction with numerous cell membrane surfaces, some at high concentrations (that is, ~108 platelets/mL), blood compatibility and resulting coagulation stimulus is an important consideration. Introduction of RGD ligands on their surfaces produces concerns that these ligands interact adversely as pro-coagulant stimuli with platelet activation triggers such as integrins. Platelets play essential roles in bleeding control through binding to each other and to other cells through integrin receptors such as αIIbβ3 and αvβ3. Like αvβ3, αIIbβ3 avidly binds RGD 54 as well as RGD-containing proteins such as fibrinogen and von Willebrand factor at moderately high affinities (10−7 M).55 However, cyclic RGDfK has been reported to bind with a much greater affinity (10−8–10−9 M),56 suggesting that RGD-targeted agents against specific tumor-based sites may exert selective binding to tumor-based cells after systemic administration despite the high competitive platelet abundance. Platelet studies focus naturally more on platelet αIIbβ ligand engagement, as only trace amounts of αvβ3 are present on platelets (~100 αvβ3 receptors per platelet vs. ~100,000 αIIbβ3 receptors).57 Based on these receptor densities, RGDfK-GNRs more than likely affect αIIbβ3 on the platelet surface compared to αvβ3.

Integrin priming has been proposed to describe integrin ligand affinity regulation, whereas integrin activation is differentiated as the process of ligand-induced propagation of intracellular signals resulting from the increase in binding affinity coupled to alterations in integrin conformation.58 However, priming is also defined as the affinity- or valency-based regulatory events enhancing ligand-binding efficiency. Hence, the terms “priming” or “activation” might be confounding in their description of integrin-associated events unless carefully defined for a specific experimental system.59

Platelet activation involving platelet integrins was shown in early studies of the platelet glycoprotein GPIIb/IIIa complex (that is, integrin αIIbβ3). In these studies, platelet activation induced conformational changes in subsequent activation of the fibrinogen binding capabilities of GPIIb/IIIa.60–62

Platelet “priming” is an altered platelet response to a secondary agonist that is influenced by prior exposure to a platelet mediator. Analogous examples of cell priming are recognized in neutrophils and myocytes.63 Certain agents are shown to not fully activate platelets, but rather increase their ability to become activated when later exposed to a second agonist, essentially “priming” platelets for activation. Numerous molecules are now identified to prime platelets, including proteins, hormones, cytokines and chemokines.64 In vivo, the vast majority of platelets encountering an injury site or biomaterial fail to adhere under flow, but continue to flow downstream within circulation despite transient contact with the wound or biomaterial.65 Corum et al. recently demonstrated that the presence of a surface-adhered platelet agonist is sufficient to prime flowing platelets, producing enhanced adhesion at downstream locations.66,67 They propose that transient interactions between platelets and agonist-covered surfaces primes these platelet populations to produce a higher propensity to activate and adhere downstream when exposed to a subsequent agonist or stimulus. Platelet αIIbβ3 integrin activation is the final step in the platelet aggregation pathway, regardless of the initial priming activating stimulus. That nanoparticles, specifically RGD-bearing GNRs, might also either prime platelets, or react as agonists to activate pre-primed platelets is the related concept explored in this manuscript.

Addition of targeted RGDfK GNRs to resting platelets resulted in minimal binding of the GNRs to the platelets based on dark field microscopy. However, upon activation of the platelets through protease-activated receptors (PAR), a substantial increase in binding was observed in a dose-dependent manner. This binding appeared to be specific as untargeted GNRs did not bind to activated platelets. Taken together, these data suggest a significant portion of RGDfK targeted GNRs bind to platelets after activation through αIIbβ3.

While dark field microscopy reveals little binding of RGDfK-labeled GNRs in the presence of unactivated platelets, it is possible that RGDfK-GNRs still alter normal platelet functions and induce platelet activation. When purified platelets were incubated with different concentrations of RGDfK GNRs, or with fixed concentrations of GNRs but over different incubation times, platelet activation markers did not change. Specifically, alpha granule release as measured by P-selectin (CD62P) expression and activation of αIIbβ were similar to levels in resting platelets and in platelets incubated with RGEfK-labeled control GNRs. In addition, activation of αIIbβ3 based PAC-1 binding appeared to be similar in the presence of RGDfK-GNRs. PAC-1 is a murine IgM-K MoAb that recognizes an epitope at or in very close proximity to the fibrinogen binding site. The binding of PAC-1 is inhibited by RGD-containing peptides, and PAC-1 and fibrinogen compete with each other for binding to GPIIb-IIIa.61,68,69

To further examine RGDfK-labeled GNR influence on platelets function, a more complex test system using whole blood was employed. In whole blood, RGDfK-targeted GNRs exhibited little observable effects on platelet activation in terms of alpha granule release and αIIbβ activation. Collectively, RGDfK-labeled GNRs appeared to exert little effect on resting platelets, while they readily interacted with thrombin-activated platelets (Figs. 3–5).

Since activated platelets use αIIbβ to prevent bleeding through binding to other platelets and cells, we sought to determine if RGDfK-labeled GNRs altered platelet function. At the concentrations tested, RGDfK-bearing GNRs were unable to block fibrinogen binding to platelet surfaces, suggesting that αIIbβ function remained intact after GNR binding. Platelet aggregation, another marker of altered function, appeared uninfluenced in both whole blood or in PRP with GNR exposure when stimulated with collagen, again suggesting platelets remained functional after interacting with RGDfK GNRs.

Significantly, RGDfK-bearing GNRs exhibited little adverse reactivity toward resting platelets. Besides their role in preventing bleeding, platelets can play significant roles in the development of blood clots and coagulopathies, leading to both myocardial infarction and stroke. The inability of RGDfK GNRs to interact with basal resting platelets and their failure to induce activation suggest that their risk for increasing thrombosis events is negligible. In addition, our functional studies demonstrate that risks for bleeding or altered coagulant response upon exposure to RGDfK GNRs to blood is also minor. RGDfK-targeted GNRs significantly impacted thrombin-activated platelets in terms of their binding, but this GNR binding exhibited little functional effect on platelet aggregation and binding of substrates. Nonetheless, higher RGDfK densities higher GNR concentrations or different RGD peptide chemistries may produce dramatically different effects on platelet functions.

To reach steady state platelet concentrations in humans of 150–450 × 109/L, ~100 × 109 are removed from the circulation each day while the same amount is created from mature megakaryocytes in the bone marrow. Platelet consumption and clearance occurs through hemostatic processes such as controlling bleeding and active, continual removal by the reticuloendothelial system in the liver and the spleen. Previous research shows that the spleen and liver play a significant role in the clearance of the majority of intravenously dosed RGD-labeled targeted agents9–17 and specifically, GNRs.10,27 With platelet turnover close to a 100 billion platelets a day, many which are activated,70 and the ability of activated platelets to bind RGDfK-labeled GNRs, the observed increase in liver and splenic clearance of targeted RGDfK GNRs10,27 could very be attributed to increased platelet uptake of these GNRs and clearance through these organs. In addition, consumption of platelets through prevention of bleeding also contributes to decreased GNR targeting efficiency. GNRs that are cleared through platelet binding, consumption and clearance mechanisms increase the local concentration of GNRs in these filtration locations, with possibly significant consequences on hemostatic parameters and local tissue GNR-induced toxicities.

While these data demonstrate the ability of RGDfK-GNRs to bind to platelets through αIIbβ3-dependent mechanisms, significance is limited in scope by the in vitro nature of the assays. We did not observe any RGDfK-GNR-dependent platelet activation or inhibition of platelet function. The addition of RGDfK-GNRs to blood circulation in vivo may prompt additional effects we cannot account for based on our in vitro assays; therefore, in vivo examination of RGDfK-GNR effects on platelet function and risks for increased thrombosis or bleeding is necessary to capture the full dynamic.

Our data demonstrate that RGDfK-labeled targeted GNRs are unable to induce platelet activation in PRP or whole blood. However, upon platelet activation with thrombin, RGDfK-labeled GNRs appear to bind to platelets through αIIbβ3-dependent mechanisms. Thus GNR-platelet binding may have consequences to hemostatic functions of platelets depending on the GNRs and local pharmacology of bioactive agents it might be carrying.

The authors thank Diana Lim for providing expert assistance in figure preparation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; contract grant numbers: R01 ES024681, 1U54 HL112311-01

Contract grant sponsor: Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Predoctoral Training Award; contract grant number: PC094496

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Mizejewski GJ. Role of integrins in cancer: Survey of expression patterns. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1999;222:124–138. doi: 10.1177/153537029922200203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jin H, Varner J. Integrins: Roles in cancer development and as treatment targets. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:561–565. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garanger E, Boturyn D, Dumy P. Tumor targeting with RGD peptide ligands-design of new molecular conjugates for imaging and therapy of cancers. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2007;7:552–558. doi: 10.2174/187152007781668706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schottelius M, Laufer B, Kessler H, Wester HJ. Ligands for mapping alphavbeta3-integrin expression in vivo. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:969–980. doi: 10.1021/ar800243b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Auzzas L, Zanardi F, Battistini L, Burreddu P, Carta P, Rassu G, Curti C, Casiraghi G. Targeting alphavbeta3 integrin: Design and applications of mono- and multifunctional RGD-based peptides and semipeptides. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:1255–1299. doi: 10.2174/092986710790936301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mas-Moruno C, Rechenmacher F, Kessler H. Cilengitide: The first anti-angiogenic small molecule drug candidate design, synthesis and clinical evaluation. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2010;10:753–768. doi: 10.2174/187152010794728639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruoslahti E. The RGD story: A personal account. Matrix Biol. 2003;22:459–465. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(03)00083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen K, Chen X. Integrin targeted delivery of chemotherapeutics. Theranostics. 2011;1:189–200. doi: 10.7150/thno/v01p0189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Line BR, Mitra A, Nan A, Ghandehari H. Targeting tumor angiogenesis: Comparison of peptide and polymer-peptide conjugates. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1552–1560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borgman MP, Aras O, Geyser-Stoops S, Sausville EA, Ghandehari H. Biodistribution of HPMA copolymer-aminohexylgeldanamycin-RGDfK conjugates for prostate cancer drug delivery. Mol Pharm. 2009;6:1836–1847. doi: 10.1021/mp900134c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bibby DC, Talmadge JE, Dalal MK, Kurz SG, Chytil KM, Barry SE, Shand DG, Steiert M. Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of RGD-targeted doxorubicin-loaded nanoparticles in tumor-bearing mice. Int J Pharm. 2005;293:281–290. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiao Y, Hong H, Matson VZ, Javadi A, Xu W, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Engle JW, Nickles RJ, Cai W, et al. Gold nanorods conjugated with doxorubicin and cRGD for combined anticancer drug delivery and PET imaging. Theranostics. 2012;2:757–768. doi: 10.7150/thno.4756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poon W, Zhang X, Bekah D, Teodoro JG, Nadeau JL. Targeting B16 tumors in vivo with peptide-conjugated gold nanoparticles. Nanotechnology. 2015;26:285101. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/26/28/285101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X, Hou Y, Tohme M, Park R, Khankaldyyan V, Gonzales-Gomez I, Bading JR, Laug WE, Conti PS. Pegylated Arg-Gly-Asp peptide: 64Cu labeling and PET imaging of brain tumor alphavbeta3-integrin expression. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1776–1783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu S. Radiolabeled multimeric cyclic RGD peptides as integrin alphavbeta3 targeted radiotracers for tumor imaging. Mol Pharm. 2006;3:472–487. doi: 10.1021/mp060049x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang C, Kligman F, Larsen CC, Kottke-Marchant K, Marchant RE. Platelet and endothelial adhesion on fluorosurfactant polymers designed for vascular graft modification. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;88:348–358. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunjachan S, Pola R, Gremse F, Theek B, Ehling J, Moeckel D, Hermanns-Sachweh B, Pechar M, Ulbrich K, Hennink WE, et al. Passive versus active tumor targeting using RGD- and NGR-modified polymeric nanomedicines. Nano Lett. 2014;14:972–981. doi: 10.1021/nl404391r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kok RJ, Schraa AJ, Bos EJ, Moorlag HE, Asgeirsdottir SA, Everts M, Meijer DK, Molema G. Preparation and functional evaluation of RGD-modified proteins as alpha(v)beta(3) integrin directed therapeutics. Bioconjug Chem. 2002;13:128–135. doi: 10.1021/bc015561+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Su ZF, Liu G, Gupta S, Zhu Z, Rusckowski M, Hnatowich DJ. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of a Technetium-99m-labeled cyclic RGD peptide as a specific marker of alpha(V)beta(3) integrin for tumor imaging. Bioconjug Chem. 2002;13:561–570. doi: 10.1021/bc0155566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poujol C, Nurden AT, Nurden P. Ultrastructural analysis of the distribution of the vitronectin receptor (alpha v beta 3) in human platelets and megakaryocytes reveals an intracellular pool and labelling of the alpha-granule membrane. Br J Haematol. 1997;96:823–835. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.d01-2109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rao SP, Ogata K, Catanzaro A. Mycobacterium avium-M. intracellulare binds to the integrin receptor alpha v beta 3 on human monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages. Infect Immun. 1993;61:663–670. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.663-670.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubartelli A, Poggi A, Zocchi MR. The selective engulfment of apoptotic bodies by dendritic cells is mediated by the alpha(v)- beta3 integrin and requires intracellular and extracellular calcium. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1893–1900. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng S, Craig WS, Mullen D, Tschopp JF, Dixon D, Pierschbacher MD. Design and synthesis of novel cyclic RGD-containing peptides as highly potent and selective integrin alpha IIb beta 3 antagonists. J Med Chem. 1994;37:1–8. doi: 10.1021/jm00027a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfaff M, Tangemann K, Muller B, Gurrath M, Muller G, Kessler H, Timpl R, Engel J. Selective recognition of cyclic RGD peptides of NMR defined conformation by alpha IIb beta 3, alpha V beta 3, and alpha 5 beta 1 integrins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20233–20238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fitzgerald LA, Phillips DR. Calcium regulation of the platelet membrane glycoprotein IIb-IIIa complex. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:11366–11374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carrell NA, Fitzgerald LA, Steiner B, Erickson HP, Phillips DR. Structure of human platelet membrane glycoproteins IIb and IIIa as determined by electron microscopy. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:1743–1749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gormley AJ, Malugin A, Ray A, Robinson R, Ghandehari H. Biological evaluation of RGDfK-gold nanorod conjugates for prostate cancer treatment. J Drug Target. 2011;19:915–924. doi: 10.3109/1061186X.2011.623701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daly ME. Determinants of platelet count in humans. Haematologica. 2011;96:10–13. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.035287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bennett JS, Berger BW, Billings PC. The structure and function of platelet integrins. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(Suppl 1):200–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwertz H, Koster S, Kahr WH, Michetti N, Kraemer BF, Weitz DA, Blaylock RC, Kraiss LW, Greinacher A, Zimmerman GA, et al. Anucleate platelets generate progeny. Blood. 2010;115:3801–3809. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-239558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weyrich AS, Denis MM, Schwertz H, Tolley ND, Foulks J, Spencer E, Kraiss LW, Albertine KH, McIntyre TM, Zimmerman GA. mTOR-dependent synthesis of Bcl-3 controls the retraction of fibrin clots by activated human platelets. Blood. 2007;109:1975–1983. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-042192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwertz H, Tolley ND, Foulks JM, Denis MM, Risenmay BW, Buerke M, Tilley RE, Rondina MT, Harris EM, Kraiss LW, et al. Signal-dependent splicing of tissue factor pre-mRNA modulates the thrombogenicity of human platelets. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2433–2440. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Denis MM, Tolley ND, Bunting M, Schwertz H, Jiang H, Lindemann S, Yost CC, Rubner FJ, Albertine KH, Swoboda KJ, Fratto CM, Tolley E, Kraiss LW, McIntyre TM, Zimmerman GA, Weyrich AS. Escaping the nuclear confines: signal-dependent pre-mRNA splicing in anucleate platelets. Cell. 2005;122:379–391. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kraemer BF, Campbell RA, Schwertz H, Franks ZG, Vieira de Abreu A, Grundler K, Kile BT, Dhakal BK, Rondina MT, Kahr WH, et al. Bacteria differentially induce degradation of Bcl-xL, a survival protein, by human platelets. Blood. 2012;120:5014–5020. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-420661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones CF, Campbell RA, Brooks AE, Assemi S, Tadjiki S, Thiagarajan G, Mulcock C, Weyrich AS, Brooks BD, Ghandehari H, et al. Cationic PAMAM dendrimers aggressively initiate blood clot formation. ACS Nano. 2012;6:9900–9910. doi: 10.1021/nn303472r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones CF, Campbell RA, Franks Z, Gibson CC, Thiagarajan G, Vieira-de-Abreu A, Sukavaneshvar S, Mohammad SF, Li DY, Ghandehari H, et al. Cationic PAMAM dendrimers disrupt key platelet functions. Mol Pharm. 2012;9:1599–1611. doi: 10.1021/mp2006054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kraemer BF, Campbell RA, Schwertz H, Cody MJ, Franks Z, Tolley ND, Kahr WH, Lindemann S, Seizer P, Yost CC, et al. Novel antibacterial activities of beta-defensin 1 in human platelets: suppression of pathogen growth and signaling of neutrophil extracellular trap formation. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002355. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vainrub A, Pustovyy O, Vodyanoy V. Resolution of 90 nm (lambda/5) in an optical transmission microscope with an annular condenser. Opt Lett. 2006;31:2855–2857. doi: 10.1364/ol.31.002855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nair S, Ghosh K, Kulkarni B, Shetty S, Mohanty D. Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia: Updated. Platelets. 2002;13:387–393. doi: 10.1080/0953710021000024394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plow EF, Marguerie GA. Induction of the fibrinogen receptor on human platelets by epinephrine and the combination of epinephrine and ADP. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:10971–10977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Plow EF, Marguerie GA. Participation of ADP in the binding of fibrinogen to thrombin-stimulated platelets. Blood. 1980;56:553–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marguerie GA, Edgington TS, Plow EF. Interaction of fibrinogen with its platelet receptor as part of a multistep reaction in ADP-induced platelet aggregation. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:154–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qian X, Peng XH, Ansari DO, Yin-Goen Q, Chen GZ, Shin DM, Yang L, Young AN, Wang MD, Nie S. In vivo tumor targeting and spectroscopic detection with surface-enhanced Raman nanoparticle tags. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:83–90. doi: 10.1038/nbt1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Neal DP, Hirsch LR, Halas NJ, Payne JD, West JL. Photo-thermal tumor ablation in mice using near infrared-absorbing nanoparticles. Cancer Lett. 2004;209:171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gibson JD, Khanal BP, Zubarev ER. Paclitaxel-functionalized gold nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11653–11661. doi: 10.1021/ja075181k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dykman L, Khlebtsov N. Gold nanoparticles in biomedical applications: Recent advances and perspectives. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2256–2282. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15166e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang X. Gold nanoparticles: Recent advances in the biomedical applications. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2015;72:771–775. doi: 10.1007/s12013-015-0529-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Conde J, Tian F, Hernandez Y, Bao C, Cui D, Janssen KP, Ibarra MR, Baptista PV, Stoeger T, de la Fuente JM. In vivo tumor targeting via nanoparticle-mediated therapeutic siRNA coupled to inflammatory response in lung cancer mouse models. Biomaterials. 2013;34:7744–7753. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Su N, Dang Y, Liang G, Liu G. Iodine-125-labeled cRGD-gold nanoparticles as tumor-targeted radiosensitizer and imaging agent. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2015;10:160. doi: 10.1186/s11671-015-0864-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Danhier F, Le Breton A, Preat V. RGD-based strategies to target alpha(v) beta(3) integrin in cancer therapy and diagnosis. Mol Pharm. 2012;9:2961–2973. doi: 10.1021/mp3002733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ruoslahti E. RGD and other recognition sequences for integrins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:697–715. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haubner R, Wester HJ, Weber WA, Mang C, Ziegler SI, Goodman SL, Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R, Kessler H, Schwaiger M. Noninvasive imaging of alpha(v)beta3 integrin expression using 18F-labeled RGD-containing glycopeptide and positron emission tomography. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1781–1785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marelli UK, Rechenmacher F, Sobahi TR, Mas-Moruno C, Kessler H. Tumor targeting via integrin ligands. Front Oncol. 2013;3:222. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tomiyama Y, Tsubakio T, Piotrowicz RS, Kurata Y, Loftus JC, Kunicki TJ. The Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) recognition site of platelet glycoprotein IIb-IIIa on nonactivated platelets is accessible to high-affinity macromolecules. Blood. 1992;79:2303–2312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Phillips DR, Charo IF, Parise LV, Fitzgerald LA. The platelet membrane glycoprotein IIb-IIIa complex. Blood. 1988;71:831–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thibault G, Tardif P, Lapalme G. Comparative specificity of platelet alpha(IIb)beta(3) integrin antagonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;296:690–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coller BS, Cheresh DA, Asch E, Seligsohn U. Platelet vitronectin receptor expression differentiates Iraqi-Jewish from Arab patients with Glanzmann thrombasthenia in Israel. Blood. 1991;77:75–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Humphries MJ, McEwan PA, Barton SJ, Buckley PA, Bella J, Mould AP. Integrin structure: Heady advances in ligand binding, but activation still makes the knees wobble. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:313–320. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(03)00112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carman CV, Springer TA. Integrin avidity regulation: Are changes in affinity and conformation underemphasized? Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:547–556. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Coller BS. A new murine monoclonal antibody reports an activation-dependent change in the conformation and/or microenvironment of the platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa complex. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:101–108. doi: 10.1172/JCI111931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shattil SJ, Hoxie JA, Cunningham M, Brass LF. Changes in the platelet membrane glycoprotein IIb. IIIa complex during platelet activation. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:11107–11114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Isenberg WM, McEver RP, Phillips DR, Shuman MA, Bainton DF. The platelet fibrinogen receptor: An immunogold-surface replica study of agonist-induced ligand binding and receptor clustering. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:1655–1663. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.6.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gresele P. Platelets in Hematologic and Cardiovascular Disorders: A Clinical Handbook. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008. p. xiii.p. 511. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gresele P, Falcinelli E, Momi S. Potentiation and priming of platelet activation: A potential target for antiplatelet therapy. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:352–360. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Godo MN, Sefton MV. Characterization of transient platelet contacts on a polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel by video microscopy. Biomaterials. 1999;20:1117–1126. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Corum LE, Hlady V. The effect of upstream platelet-fibrinogen interactions on downstream adhesion and activation. Biomaterials. 2012;33:1255–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.10.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Corum LE, Eichinger CD, Hsiao TW, Hlady V. Using microcontact printing of fibrinogen to control surface-induced platelet adhesion and activation. Langmuir. 2011;27:8316–8322. doi: 10.1021/la201064d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bennett JS, Shattil SJ, Power JW, Gartner TK. Interaction of fibrinogen with its platelet receptor. Differential effects of alpha and gamma chain fibrinogen peptides on the glycoprotein IIb-IIIa complex. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:12948–12953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shattil SJ, Motulsky HJ, Insel PA, Flaherty L, Brass LF. Expression of fibrinogen receptors during activation and subsequent desensitization of human platelets by epinephrine. Blood. 1986;68:1224–1231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Machlus KR, Italiano JE., Jr The incredible journey: From megakaryocyte development to platelet formation. J Cell Biol. 2013;201:785–796. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201304054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.