Abstract

Background

Contemporary cochlear implants use cathodic-leading, symmetrical, biphasic current pulses, despite a growing body of evidence that suggests anodic-leading pulses may be more effective at stimulating the auditory system. However, since much of this research on humans has used pseudomonophasic pulses or biphasic pulses with unusually long interphase gaps, the effects of stimulus polarity are unclear for clinically relevant (i.e., symmetric biphasic) stimuli.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of stimulus polarity on basic characteristics of physiological spread-of-excitation (SOE) measures obtained with the electrically-evoked compound action potential (ECAP) in cochlear implant recipients using clinically relevant stimuli.

Research Design

Using a within-subjects (repeated measures) design, we examined the differences in mean amplitude, peak electrode location, area under the curve, and spatial separation between SOE curves obtained with anodic- and cathodic-leading symmetrical, biphasic pulses.

Study Sample

Sixteen cochlear implant recipients (ages 13–77) participated in this study. All were users of Cochlear Corp. devices.

Data Collection and Analysis

SOE functions were obtained using the standard forward-masking artifact reduction method. Probe electrodes were 5–18, and were stimulated at an 8 (of 10) loudness rating (“loud”). Outcome measures (mean amplitude, peak electrode location, curve area, and spatial separation) for each polarity were compared within subjects.

Results

Anodic-leading current pulses produced ECAPs with larger average amplitudes, greater curve area, and less spatial separation between SOE patterns, compared with that for cathodic-leading pulses. There was no effect of polarity on peak electrode location.

Conclusions

These results indicate that for equal current levels, the anodic-leading polarity produces broader excitation patterns compared with cathodic-leading pulses, which reduces the spatial separation between functions. This result is likely due to preferential stimulation of the central axon. Further research is needed to determine whether SOE patterns obtained with anodic-leading pulses better predict pitch discrimination.

Keywords: Cochlear implant, electrically-evoked compound action potential, spread of excitation, stimulus polarity

Introduction

Physiological spread of excitation (SOE) in the electrically stimulated cochlea can be estimated using the electrically evoked compound action potential (ECAP) in individuals with cochlear implants (CIs) (e.g., Cohen et al, 2003; Abbas et al, 2004; Hughes and Stille, 2010). SOE patterns are typically obtained using a forward-masking paradigm, where the masker stimulus is roved across the array while the location of the probe and recording electrode are fixed. With this method, the ECAP amplitude is usually largest when the masker and probe are delivered to the same electrode. SOE patterns that are obtained using forward masking reflect the amount of overlap between populations of stimulated neurons, and can therefore be used to approximate the spatial resolution within the electrically stimulated cochlea. Studies investigating how SOE patterns relate to pitch perception have produced mixed results. Hughes and Abbas (2006) found no relation between the width of the SOE function and pitch ranking; however, a follow-up study (Hughes 2008) characterized the ECAP functions in a novel way by calculating the amplitude differences between pairs of SOE functions, and then summing those differences across all masker electrodes. Using this method to quantify the spatial separation between SOE functions, the authors found a significant correlation between greater spatial separation of SOE patterns and better pitch ranking. When a similar comparison was applied to adjacent physical electrodes and intermediate channels, however, the relation was generally positive but not statistically significant (Goehring et al, 2014a,b). It was concluded that although the ECAP SOE has some utility for predicting pitch ranking for physical electrodes, it is not sensitive enough to predict pitch ranking for intermediate or virtual channels.

One variable that might affect the relation between physiology and perception is the polarity of the stimulus. Commercially available cochlear implants use cathodic-leading pulses, likely because this type of stimulus has been shown to be most effective at stimulating the auditory nerve in animal models (e.g., Miller et al, 1999; Klop et al, 2004). Conversely, recent physiological evidence in humans using the ECAP suggests that anodic-leading pulses may be more effective at stimulating the auditory nerve (Macherey et al, 2008; Undurraga et al, 2010; 2012; Hughes et al, 2017). Results from these studies suggest that more effective stimulation might result in more effective masking when the forward-masking paradigm is used to derive the spread of excitation (Undurraga et al, 2012). In a recent study using symmetrical biphasic pulses with an interphase gap (Cochlear devices), Hughes et al (2017) found larger ECAP amplitudes using the forward-masking method when the masker and probe were both anodic-leading versus cathodic-leading.

With the forward-masking subtraction method (e.g., Abbas et al, 1999), four stimulus frames are applied: (A) probe alone (to elicit the ECAP), (B) masker and probe with a short masker-probe interval (typically 400–500 μsec) to isolate the probe artifact, (C) masker alone (to obtain a recording of any residual neural response and artifact produced by the masker), and (D) zero-amplitude pulse (to isolate system artifact). The ECAP is derived by the following formula: A-B+C-D. When the masker and probe are delivered to the same electrode, both stimuli presumably recruit the same population of neurons. The response to the masked probe in frame B should therefore only contain stimulus artifact because the neurons are driven into a refractory state by the preceding masker. This results in a maximal ECAP amplitude when subtracted from the probe-alone trace in frame A. When the masker and probe are spatially separated, the response to the probe is not fully masked in frame B. Fibers responding to the probe in this case represent neurons that are not recruited by the masker. The partial ECAP response to the probe in frame B is subtracted from the response in frame A, resulting in a reduced ECAP amplitude that represents the spatial overlap between masker and probe electrodes. If anodic-leading pulses result in greater activation of the auditory nerve (as seen in recent human studies), responses to both the masker and probe should be enhanced, producing broader regions of excitation. Therefore, the partial ECAP response to the probe in frame B should be smaller for anodic stimulation than for cathodic because of more effective masking. In the subtracted trace, ECAPs should be larger for anodic than for cathodic-leading stimulation, resulting in an overall broader excitation pattern for anodic-leading stimuli. Using asymmetric pulses in monopolar mode, Undurraga et al. (2010) were only able to record ECAPs using anodic maskers, suggesting that stimulation with this phase resulted in the most effective masking. The goal of the present study was to investigate the extent to which stimulus polarity affects basic characteristics of ECAP SOE patterns using symmetrical biphasic pulses that are used clinically. If anodic-leading stimuli produce a more accurate estimation of the SOE, we may see a stronger relation between physiological SOE patterns and perceptual measures.

Previous research on polarity sensitivity has shown differing results in animals and humans. Research on the electrically stimulated auditory nerve in animal models has shown that action potentials generated by cathodic stimuli typically arise from the peripheral axon (Miller et al, 1998; Miller et al, 1999; Rattay et al, 2001a; Klop et al, 2004). In humans, electrophysiological studies with pseudomonophasic pulses have consistently demonstrated greater sensitivity to the anodic phase, yielding shorter latencies and larger amplitudes than for cathodic stimulation (Macherey et al, 2008; Undurraga et al, 2010; 2012; 2013). Modeling work by Rattay et al. (2001b) showed that biphasic cathodic and anodic stimuli are equally effective in generating action potentials when peripheral processes are present. However, once peripheral axons have been lost, the cathodic phase requires more current to overcome the unmyelinated soma for action potential propagation. Because the anodic phase preferentially stimulates the central axon, less current is needed to generate an action potential. Peripheral loss in animal experiments tends to be minimized because of acute deafening procedures (e.g. Miller et al, 1998; Klop et al, 2004), whereas peripheral loss tends to be much more extensive for most CI users due to longer durations of hearing loss and deafness (e.g., Hinojosa and Marion, 1983; Nadol et al, 1997; Ng et al, 2000; Kahn et al, 2005). These differences likely contributed to conflicting findings between humans and animals.

Few studies have examined stimulus polarity effects on ECAP responses obtained in humans using symmetrical biphasic pulses that are used clinically. Undurraga et al. (2010) found larger ECAP amplitudes and shorter latencies for anodic-leading pulses in a group of four Advanced Bionics CI recipients. In contrast, Macherey et al. (2008) reported similar ECAP amplitudes for anodic- and cathodic-leading pulses in a group of six Advanced Bionics recipients, despite both studies using the same stimulus paradigm. The lack of consensus between studies suggests the effects of polarity on the auditory nerve are poorly understood and may be influenced by a number of factors, including the degree of neural degeneration and differences in supra-threshold versus threshold responses (Carlyon et al, 2013).

To date, only one study has examined the effect of stimulus polarity on ECAP SOE patterns. Undurraga et al. (2012) used symmetric cathodic- or anodic-leading biphasic pulses with a long interphase gap (2.1 ms) presented in bipolar mode to simulate monophasic stimulation. The authors described the resultant SOE patterns in terms of the centroid of the SOE function and the SOE width (the number of electrodes between 25% and 75% in the cumulative SOE function). The results showed that the centroid corresponded to the electrode that delivered the anodic phase, although the width of the function was not different between polarities. These results held true for pseudomonophasic stimuli and when pulses were presented in a narrow bipolar mode (3-electrode separation versus 9). The authors concluded that the anodic polarity is the most effective phase of a biphasic pulse, likely due to more effective stimulation and/or masking.

The purpose of the present study was to examine the effects of polarity on basic characteristics of ECAP SOE patterns using clinically relevant stimuli. Much of the previous work in humans has been done with stimuli that simulate the monophasic pulses used in most animal research (e.g., pseudomonophasic pulses or symmetric biphasic pulses with unusually long interphase gaps). Because these pulse designs are not used clinically, the effects of polarity remain largely unknown for standard symmetrical biphasic stimuli delivered in monopolar mode. Based on recent findings that showed the anodic phase of a symmetrical biphasic pulse is more effective if it is presented first (Hughes et al, 2017), we predicted that anodic-leading pulses will produce SOE patterns with larger overall amplitudes, broader curves (due to stimulation of the central axon), and therefore less spatial separation between patterns when compared to cathodic-leading pulses. It was also hypothesized that polarity would have no significant effect on shifting the peak of the SOE function for monopolar stimulation. For bipolar stimuli, forward-masking functions can produce dual-peaked functions (e.g., Chatterjee et al, 2006; Zhu et al, 2012). Undurraga et al (2012) showed that the centroid of bipolar SOE functions occurred around the electrode that delivered the anodic phase. Because monopolar stimulation does not tend to produce forward-masking functions with two peaks, the location of the peak electrode was not expected to be affected by polarity.

The results from this study will provide the foundation for subsequent investigations into the role of polarity on the relation between physiological and perceptual measures. If cathodic-leading symmetrical biphasic pulses produce less effective masking, the subtraction method used to derive the ECAP will result in smaller amplitudes and narrower SOE functions. As such, SOE functions for cathodic-leading stimuli might not accurately represent the actual stimulation patterns that contribute to place-pitch estimates.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Data were collected for 16 cochlear-implant recipients ages 13–77 years (mean, 55.1 years). Six subjects were implanted bilaterally. For subject F10/F11, both ears were tested. For the other five subjects with bilateral CIs (F1, F5, F17, FS22, N11,), only the ear listed in Table 1 was used because the opposite ear either had an older-generation device or very small/absent ECAPs. All participants were users of newer-generation Cochlear Corp. devices. Seven subjects used the Nucleus 24RE(CA), five subjects used the CI422, two subjects used the CI512, and two subjects used the CI522 (the CI422 and CI522 are straight arrays, whereas the others are perimodiolar). Importantly, all devices utilized the same internal electronics package. Demographic data for all subjects can be found in Table 1. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Boys Town National Research Hospital under protocol 03-07-XP, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Table 1.

Demographic information for study participants. L, left; R, right; IS, initial stimulation; CI, cochlear implant; HL, hearing loss.

| Subject | Internal Device | Ear | Dur. Deafness (yrs, mos) | Age at IS (yrs, mos) | Dur. CI Use (yrs, mos) | Etiology, Onset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 24RE(CA) | L | 11,3 | 60,7 | 10,2 | Unknown/Progressive |

| F2 | 24RE(CA) | R | 10,6 | 60,3 | 9,0 | Unknown/Progressive |

| F5 | 24RE(CA) | R | 7,7 | 48,3 | 7,11 | Unknown/Sudden from established HL |

| F10 | 24RE(CA) | R | 1,10 | 1,10 | 10,7 | Waardenburg Syndrome/Congenital |

| F11 | 24RE(CA) | L | 8,3 | 8,3 | 17,0 | Waardenburg Syndrome/Congenital |

| F17 | 24RE(CA) | R | 11,0 | 42,11 | 10,4 | Congenital/Progressive |

| F27 | 24RE(CA) | L | 10,5 | 56,2 | 2,0 | Otosclerosis/Progressive |

| N7 | CI512 | R | 10,11 | 69,9 | 5,8 | Unknown/Progressive |

| N11 | CI512 | L | 6,0 | 67,5 | 5,0 | Unknown-Familial & Noise Exposure/Progressive |

| N23 | CI512 | R | 1,10 | 70,5 | 2,7 | Menieres |

| FS22 | CI422 | L | 2,3 | 13,9 | 3,2 | Meningitis/Progressive |

| FS28 | CI422 | R | 3,8 | 72,6 | 1,10 | Unknown/Progressive |

| FS31 | CI422 | R | 30 | 76,4 | 1,3 | Noise Induced/Hereditary |

| FS32 | CI422 | L | 8,4 | 58,9 | 3,2 | Unknown/Hereditary & Progressive |

| FS33 | CI422 | R | 0* | 12,0 | 1,11 | Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder/Congenital |

| NS20 | CI522 | R | 28,9 | 31,9 | 0,8 | Illness/Unknown |

Participant had mild-moderate hearing loss.

Equipment Setup

All ECAP measures were made using the commercial Custom Sound EP (v 4.3) software (Cochlear Ltd., Macquarie, New South Wales, Australia). Stimuli were presented through a laboratory Freedom sound processor and programming pod.

Stimuli and Procedure

ECAPs were obtained using symmetric, biphasic current pulses presented in monopolar mode. Both the masker and probe stimuli generally used the following parameters: 25-μsec/phase pulse duration, 50-dB gain, 400-μsec masker–probe interval, 80-Hz stimulation rate, and 100 averages. Monopolar stimulation was relative to the extracochlear ball electrode, MP1, and recording was relative to the extracochlear case electrode, MP2. The intracochlear recording electrode was fixed two electrode positions apical to the location of the probe. For some probe electrodes, the recording electrode was three electrodes apical to the probe in order to optimize waveform morphology by further reducing stimulus artifact. Pulse duration was set to 50 μsec/phase for some participants (F10, F11, F17, FS28, FS32, N5, N7, and N23) due to issues with exceeding voltage compliance (described further below). The polarity of the leading phase was either cathodic (e.g. 5-MP1) or anodic (e.g. MP1–5) for both the masker and probe. The traditional forward-masking subtraction technique was used to remove stimulus artifact from the recording (e.g., Abbas et al, 1999). SOE patterns were obtained by fixing the probe and recording electrode locations and roving the masker electrode across the array. All parameters except recording delay (which was individually adjusted to optimize the ECAP) were kept the same within a subject across SOE patterns.

An ascending loudness-scaling technique was used to determine stimulation levels for the SOE measures. Because our goal was to compare SOE measures between polarities at the same CL, loudness measures were only obtained using the anodic-leading stimulus because it is typically louder than a cathodic-leading stimulus (Macherey et al, 2006 for pseudomonophasic pulses; Macherey et al, 2008 for pseudomonophasic pulses with a long interphase gap; Carlyon et al, 2013 for triphasic pulses). Five sweeps of the four-frame masker-probe anodic-leading stimulus were presented to a single electrode beginning at an inaudible level and then slowly increased in 5-CL steps. Participants were instructed to use a 10-point loudness-rating scale to indicate when the sound was an “8” (“loud”). This procedure was repeated until an “8” level had been determined for all 22 electrodes. All masker and probe stimuli for both leading polarities were presented at the corresponding “8” level for each electrode obtained using the anodic-leading stimulus. For one subject with a mild developmental delay (FS33), the reported “8” levels were much lower than those from a previous session, yielding ECAP amplitudes that were difficult to distinguish from the noise floor. Stimulation levels were therefore set between the “8” levels given at the two visits, and the participant did not indicate that any of the stimuli were too loud. For some subjects who exceeded voltage compliance before an “8” level could be reached (F17, FS31, N23, F2, NS20), stimuli were presented at an equal loudness level across the array that was just below voltage compliance limits. If ECAPs were not large enough to interpret just below compliance limits at a pulse duration of 25 μsec/phase, a pulse duration of 50 μsec/phase was used for the participants previously mentioned. For each participant, SOE curves were collected for 14 probe electrodes for both polarities. This resulted in a total of 28 SOE functions per participant. Three electrode regions were tested. Regions were designated as basal (electrodes 5–9), middle (9–13), or apical (14–18). For one subject (F2), electrodes 3–7 were used for the basal set due to an open circuit on electrode 8. Electrodes 13–17 were used for the apical set for this subject in order to maintain 14 distinct probe electrodes per participant. For each region, the middle electrode in the set (e7 for basal, e11 for middle, and e16 for apical) was used as a reference electrode for comparison to the other four electrodes to calculate the spatial separation between probe-electrode SOE patterns within each polarity. For example, in the basal group the reference electrode was 7, so comparison pairs were 5–7, 6–7, 8–7, and 9–7 (see Figure 1E). These pairs were chosen because they will also be used for a subsequent study comparing the effects of stimulus polarity on the relation between physiological spatial separation and pitch ranking.

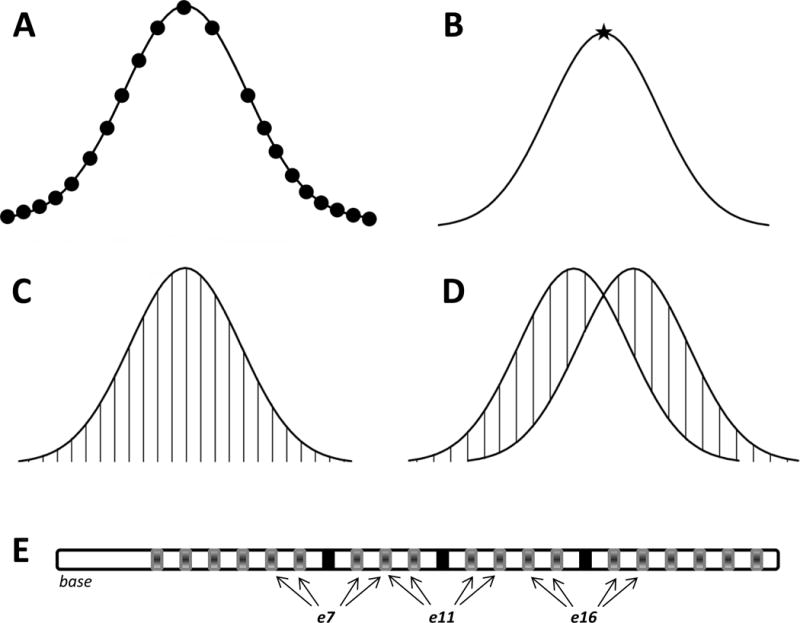

Figure 1.

Schematic of outcome metrics. Each curve represents a hypothetical SOE pattern. A) Mean amplitude was calculated by averaging ECAP responses across all masker electrodes (black circles), excluding the recording electrode (empty space). B) Peak electrode was the masker electrode number that generated the largest ECAP amplitude across each SOE function (black star). C) Area under the curve (sum of vertical lines) was calculated as the cumulative sum of normalized ECAP amplitudes in the function after interpolating for the recording electrode. D) Spatial separation between SOE functions was calculated as the sum of the absolute value of the difference in normalized amplitude between paired functions for each masker electrode location (sum of vertical lines). E) Depiction of the electrode array showing probe pairs used to calculate spatial separation. The three regions are denoted by three sets of arrows. Reference electrodes (e7, e11, and e16) are shown using black rectangles. Arrows point to the other electrodes (shown using grey rectangles) that are compared to these reference electrodes.

Data Analysis

ECAP amplitudes were calculated as the difference between the first negative trough (N1) and the following positive peak or plateau (P2). These peaks are automatically marked in the Custom Sound EP software; however, all peak markers were verified or adjusted as necessary by the investigators. Data were then exported and processed using custom Matlab scripts (Mathworks, Natick, MA). The following calculations were made for each SOE function (see Figure 1 for a schematic of each metric):

Mean ECAP amplitude. For each probe-electrode SOE function, amplitudes were averaged across all masker electrodes (excluding the recording electrode) to obtain the mean ECAP amplitude. Figure 1A shows a schematic of the 21 ECAP amplitudes that are averaged together to generate the mean. Mean amplitudes were compared between polarities to determine if one polarity yielded larger average amplitudes than the other.

Electrode location of the peak of the SOE function. The peak of the SOE function was the masker electrode number that generated the largest ECAP amplitude across each SOE function. Figure 1B shows a schematic of the location of the peak (indicated by the star). The location of the peak was compared between SOE patterns produced by anodic- and cathodic-leading stimuli to determine whether polarity shifted the location of the peak of the function.

Area under the SOE curve. In most cases, the ECAP cannot be recorded from the same electrode that provides the stimulus because of excessive artifact (typically amplifier saturation). Because the location of the recording electrode differed in some cases, and measures from all electrodes are needed to determine the area under the SOE curve using our earlier method (Hughes, 2008), the amplitude of the ECAP from the recording electrode was estimated using linear interpolation (also for the open-circuit electrode for F2). This was done by averaging the two ECAP amplitudes for masker electrodes directly adjacent on either side of the recording electrode1. Next, all ECAP amplitudes were normalized to the peak amplitude within each SOE function to control for overall amplitude differences across subjects, electrodes, and polarities so that the area-under-the-curve measure more directly reflects the breadth of each function. The area under the curve was calculated as the cumulative amplitude of all normalized ECAP amplitudes in the function. (Note this is not a true “area” calculation; however, we will use the term “area under the curve” throughout this report for simplicity.) Figure 1C depicts a schematic of the data points used to determine area under the curve. This metric was used in favor of measuring the width of the curve at a designated down-point because it is less influenced by asymmetric curves (Hughes and Abbas, 2006). The areas under the curve for SOE functions obtained with anodic-leading versus cathodic-leading stimuli were compared to determine if polarity systematically affected the overall breadth of the function.

Spatial separation between SOE functions. The goal of this metric was to determine whether the spatial separation between pairs of cathodic-leading SOE functions differed from that between pairs of anodic-leading SOE functions. To quantify the spatial separation between pairs of SOE functions within each polarity, ECAP amplitudes were first normalized to the single peak amplitude across both functions within each comparison pair. This method preserves relative amplitude differences between comparison pairs (see Hughes, 2008), but avoids the confound of overall amplitude differences between polarities. Because ECAP amplitudes are generally larger for anodic-leading than for cathodic-leading stimuli (Macherey et al, 2008; Undurraga et al, 2010; Hughes et al, 2017), the spatial separation between anodic pairs versus cathodic pairs will be affected by the raw amplitude differences between polarities if the data are not normalized. The absolute value of the difference in normalized amplitude between paired functions for each masker electrode location was then calculated (Hughes, 2008; Hughes et al, 2013; Goehring et al, 2014a). These differences were summed together to yield the spatial separation index, Σ. Figure 1D shows a schematic of this calculation. In total, there were 12 comparison pairs per subject, with 4 pairs in each region (basal, middle, and apical). Each electrode was compared to the reference electrode in the center of that region, as depicted in Figure 1E. The Σ values for all anodic-leading SOE pairs were compared to those for the respective cathodic-leading SOE pairs to determine if polarity affected the amount of spatial separation between functions.

Statistical analyses were performed in SigmaPlot (v. 12.5, Systat Software, San Jose, CA). For each outcome measure (amplitude, peak location, area, and spatial separation), a non-parametric version of the paired Student’s t-test (Wilcoxon Signed Rank test) was used to compare measures made with anodic- versus cathodic-leading stimuli. A nonparametric test was used because the data were not normally distributed. For non-parametric tests, medians are typically reported in lieu of means because means can be skewed when the data do not follow a normal distribution. We have, however, reported both medians and means where possible. Last, electrode was not considered as a factor in the analysis because variations in insertion depth and electrode-modiolar distance (particularly for perimodiolar arrays) are large and unsystematic across individuals (Saunders et al, 2002), which precludes clear interpretation of any potential statistical effects of electrode as a factor.

Results

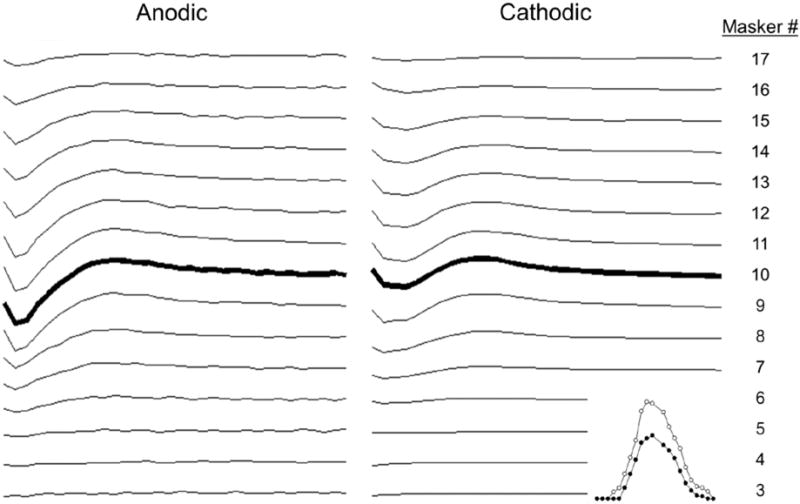

Figure 2 shows ECAP waveforms for anodic-leading (left) and cathodic-leading (right) stimuli. Data are from probe e10 in subject N23. Masker electrode numbers are indicated at the right side of the figure in an apical (top) to basal (bottom) direction. Bolded waveforms represent the ECAP obtained with the masker and probe on the same electrode (e10). The corresponding SOE patterns are shown as an inset at the bottom right of the figure. In this example, ECAP amplitudes were larger overall for anodic-leading (white circles in the inset) than for cathodic-leading (black circles) stimuli. ECAPs were obtained for more masker electrodes for the anodic-leading polarity than for cathodic, leading to broader SOE patterns. The peak of the SOE function obtained with anodic-leading stimuli occurred at e10 (also the probe electrode), whereas the peak for the cathodic-leading condition occurred at e11.

Figure 2.

Example waveforms and SOE patterns (figure inset) for subject N23. ECAP responses obtained for anodic- (left column) and cathodic-leading (right column) pulses with the probe fixed on electrode 10. Masker electrodes are listed at the far right from apical (top) to basal (bottom). The bolded waveforms represent the masker and probe on the same electrode. The SOE patterns derived from these waveforms are shown in the inset at the bottom right corner. Peak-to-peak amplitudes are plotted as a function of masker electrode from left (basal) to right (apical). White symbols, anodic-leading pulses; black symbols, cathodic-leading pulses).

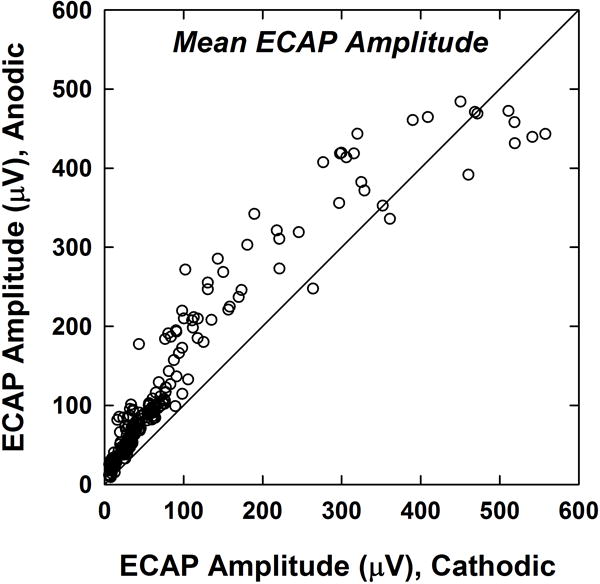

Figure 3 shows the mean ECAP amplitudes for anodic-leading compared to cathodic-leading stimuli. For each of the 16 subjects, SOE functions for 14 probe electrodes (see Figure 1E) were collected for each polarity. The solid diagonal line represents equal amplitude for both polarities. Data points that fall above the line represent probe electrodes that exhibited larger amplitudes for anodic-leading stimuli. Although most raw ECAP amplitudes were less than 100 μV, some participants had relatively large mean amplitudes (approximately 300–500 μV). For all but the largest ECAP responses, anodic-leading stimuli generally produced larger amplitudes. A Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test indicated that the median ECAP amplitude for anodic-leading (77.9 μV) pulses was significantly larger than the median amplitude for cathodic-leading (38.0 μV) pulses (z = −11.704, p < .001). The mean ECAP amplitudes for anodic- and cathodic-leading stimuli were 124.1μV and 86.7 μV, respectively. This result confirmed the hypothesis that anodic-leading pulses produce larger ECAP responses.

Figure 3.

ECAP amplitudes for anodic-leading compared to cathodic-leading stimuli. Each dot represents the mean ECAP amplitude across the SOE pattern for one probe electrode for one subject (14 probes per subject; 224 total data points). The diagonal line denotes equal amplitudes for both polarities. Data points above the diagonal line represent larger amplitudes for anodic-leading stimuli.

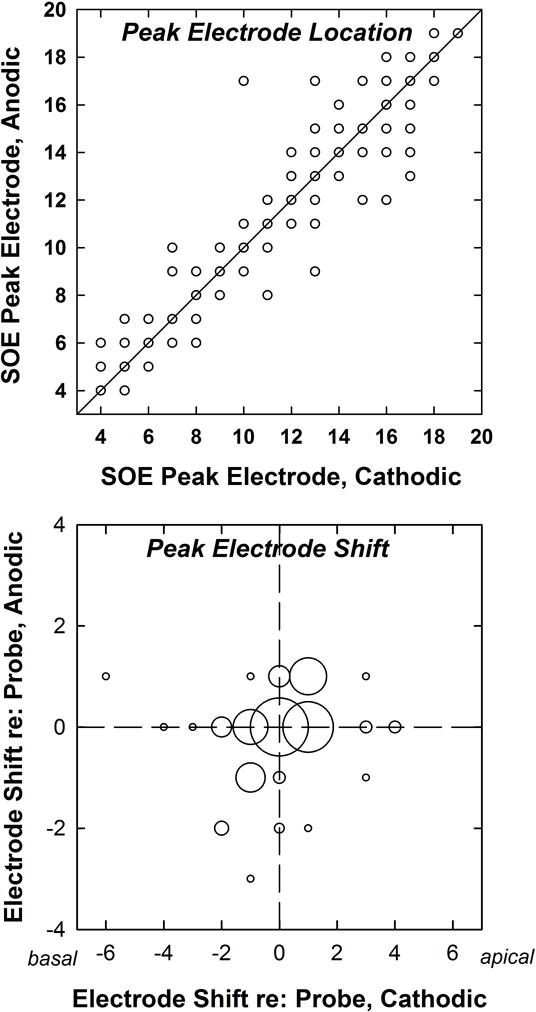

The top panel of Figure 4 shows the peak electrode location compared between polarities. Each subject contributed 14 SOE functions to the data analysis. The solid diagonal line represents the same peak location for both polarities. Note that some of the data points overlie each other. There was no significant effect of polarity on peak electrode location (Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test, z = 1.464, p = .144), as expected. The bottom panel of Figure 4 is a bubble plot that indicates the degree to which the peak was shifted relative to the location of the fixed probe. In this figure, negative shifts reflect peaks that occurred basal to the probe and positive shifts reflect peaks that occurred apical to the probe. The size of the bubbles reflects the number of SOE patterns at each coordinate. The peak occurred at the same electrode for both polarities for slightly more than half (114/224) of the pairs of SOE functions. For 66 of these pairs, the peak occurred at the probe electrode (zero-electrode shift on both axes). For 27 pairs, the peak was shifted one electrode position apically (+1) for both polarities; for 17 pairs, the peak was shifted one electrode position basally (−1) for both polarities; and for 4 pairs, the peak was shifted two electrode positions basally (−2). The eight smallest bubbles each represent one cathodic/anodic pair of SOE functions. The minimum shift in peak electrode location from the probe electrode location was zero electrodes for both polarities. The maximum shift was ±3 electrodes for the anodic-leading stimulus and −6 to +4 electrodes for the cathodic-leading stimulus. The average shift in electrode location was 0.34 electrodes for the anodic polarity and 0.83 electrodes for the cathodic. In summary, stimulus polarity did not shift the peak of the SOE function in any predictable way.

Figure 4.

Top: Electrode location of the peak of the SOE function for anodic-leading compared to cathodic-leading stimuli. Each dot represents the peak electrode location of an SOE pattern for one probe electrode for one subject (14 per subject; 224 total data points). The diagonal line denotes equal peak electrodes for both polarities. Bottom: Bubble plot indicating the degree to which the peak of the SOE function shifted relative to the probe electrode. Negative and positive numbers represent the number of electrodes by which the peak shifted in the basal or apical direction, respectively. Bubble size corresponds to the number of occurrences at each coordinate, where the largest bubble represents 66 SOE functions and the smallest eight bubbles each represent one SOE function.

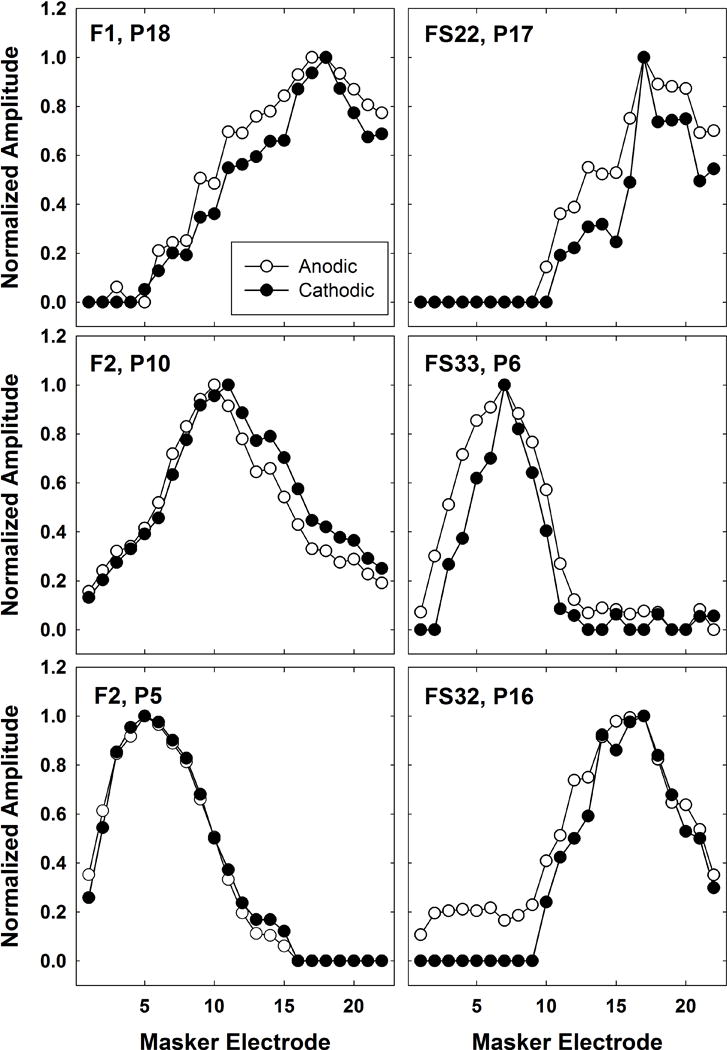

Figure 5 shows six individual examples of pairs of SOE patterns obtained with each leading polarity. In each panel, both SOE patterns have been normalized to the peak of each respective function so that the area under each curve could subsequently be calculated and compared. These examples show the range of patterns that were observed. Subject numbers and probe electrodes are indicated in each panel. For subjects F1, FS22, and FS33, the SOE function obtained with the anodic-leading polarity yielded broader patterns on both the apical and basal sides of the function. For F2 (P10), the cathodic-leading polarity yielded a broader function on the apical side of the peak. In contrast, the anodic-leading polarity yielded a broader function on the basal side of the peak for FS32. Finally, virtually no polarity effects were demonstrated for probe e5 in subject F2.

Figure 5.

Individual examples of pairs of normalized SOE patterns obtained with anodic-leading (open circles) and cathodic-leading (filled circles) stimuli. Each pattern has been normalized to the peak of its own function to allow for comparisons of area under the curve while controlling for overall amplitude differences. Subject number and probe electrode are indicated on each panel.

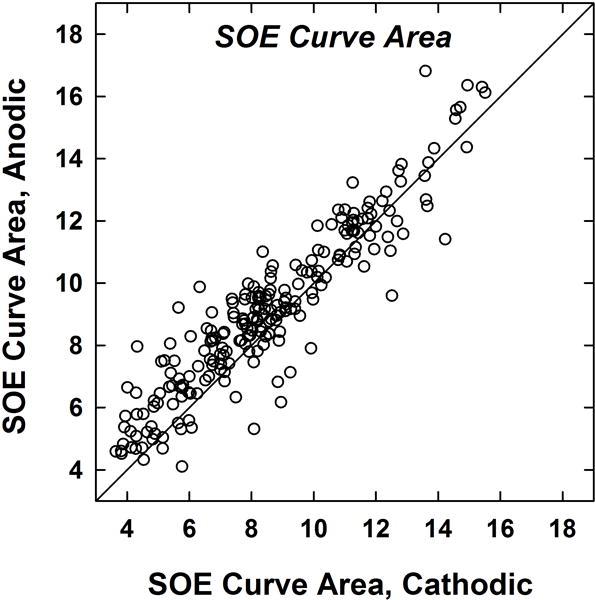

Figure 6 shows the mean curve areas for normalized SOE functions produced by anodic- and cathodic-leading pulses. The data represent SOE functions from 14 probe electrodes per subject. The solid diagonal line represents equivalence between polarities. Data points that fall above the diagonal line represent broader functions (larger curve areas) for anodic-leading stimuli. The median curve area was significantly greater for anodic-leading (8.9) than for cathodic-leading (8.2) stimuli (Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test, z = −8.358, p < .001). Mean curve areas were 9.1 for anodic-leading and 8.5 for cathodic-leading stimuli. This result is consistent with the hypothesis that anodic-leading pulses produce broader excitation patterns than cathodic-leading stimuli.

Figure 6.

Area under the curve (see text) for normalized SOE functions obtained with each polarity. Each dot represents an SOE pattern for one probe electrode for one subject (14 per subject; 224 total data points). The diagonal line denotes equal curve areas for both polarities. Data points above the diagonal represent larger curve areas (broader SOE patterns) for anodic-leading stimuli.

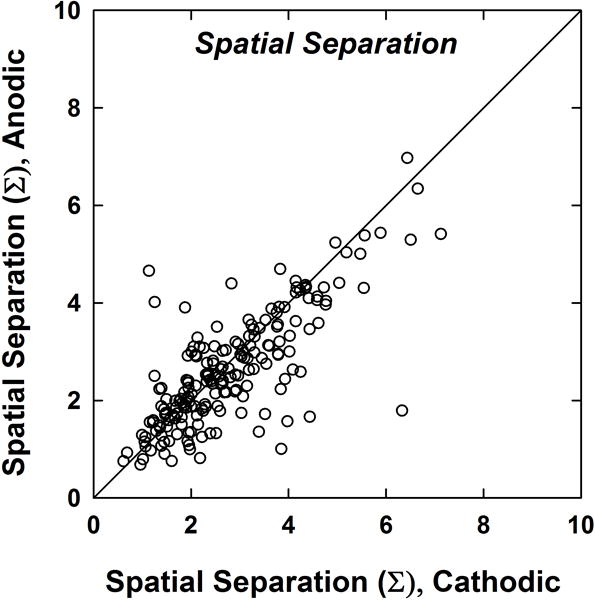

Figure 7 shows the calculated spatial separation index, Σ, for pairs of SOE functions obtained with cathodic-leading (abscissa) and anodic-leading (ordinate) stimuli. The 192 data points represent Σ values from 12 SOE probe pairs per subject. As expected, more data points fell below the diagonal line, indicating less spatial separation between comparison pairs for anodic-leading than for cathodic-leading stimuli. A Wilcoxon Signed Rank test showed that the median spatial separation for cathodic-leading pulses (2.51) was significantly larger (z = 3.16, p = .002) than for anodic-leading stimuli (2.43). The mean cathodic-leading spatial separation (2.8) was also slightly larger than the mean anodic-leading spatial separation (2.6). These results confirm the hypothesis that more effective masking by anodic stimuli leads to larger (i.e., broader) curve area and thus less spatial overlap between SOE patterns for anodic-leading stimuli.

Figure 7.

Spatial separation between SOE functions (normalized by comparison pairs). Each dot represents the spatial separation between two SOE patterns for one subject (12 pairs per subject; 192 total data points). The diagonal line denotes equal peak electrodes for both polarities. Data points below the diagonal represent greater spatial separation for cathodic-leading stimuli.

Discussion

In this study, ECAP SOE patterns for cathodic-leading symmetrical biphasic pulses were compared to those for anodic-leading pulses to examine the effects of polarity on basic characteristics of SOE patterns using clinically relevant stimuli. In general, anodic-leading pulses produced larger ECAP amplitudes, broader SOE patterns, and consequently less spatial separation between functions. These results appear to support existing evidence that the anodic phase preferentially and more effectively stimulates the central axon in the deafened ear. When the anodic phase is presented first as part of a biphasic pulse, it produces greater masking than when presented immediately following a cathodic phase. Finally, polarity appears to have no consistent effect on the location of the peak electrode in the SOE curve.

Amplitudes

Larger ECAP amplitudes were generally observed for the anodic-leading polarity compared with the cathodic-leading polarity (see Fig. 3), consistent with the findings of Undurraga et al. (2010) for symmetrical biphasic pulses. This supports the central axon as the site of excitation, as anodic stimuli preferentially stimulated the axon in the degenerated auditory nerve models described by Rattay et al. (2001a, b). Furthermore, auditory neurons are more tightly bundled at the central axon, which may lead to greater spread of excitation for direct axonal stimulation (Rattay et al, 2001b).

Although the stimuli for both leading polarities were presented at the same CL, the respective loudness levels might not have been equal between polarities. Indeed, anodic pulses have been shown to be louder than cathodic pulses at equal CL for triphasic (Carlyon et al, 2013) and pseudomonophasic (Macherey et al, 2006, 2008; Undurraga et al, 2013) pulse shapes. Louder percepts could result from recruitment of a larger population of neurons (i.e., from axonal stimulation), resulting in larger ECAP responses and broader SOE patterns than for softer percepts. If the CL of the anodic-leading stimulus is reduced to match the loudness of the cathodic-leading stimulus, then the anodic SOE patterns would likely have smaller amplitudes and narrower widths at these lower levels (Hughes and Stille, 2010). Therefore, SOE patterns might look similar for both polarities when current levels are set according to similar loudness ratings (as is done during clinical programming). If the cathodic-leading polarity truly produces less effective masking (Undurraga et al, 2012), then the breadth of the cathodic SOE obtained with present measurement techniques might be underestimated. Consequently, at equal loudness levels, it is possible that the spatial excitation patterns might be different. It is unclear what effect polarity would have on speech perception using contemporary processing strategies.

Poor nerve survival, as measured by spiral ganglion cell counts, has been shown in individuals with severe-profound hearing loss (e.g., Kawano et al, 1998; Nadol et al, 2001), such as the CI recipients who participated in this study. Spiral ganglion cells counts have also been shown to be reduced for older individuals and for longer durations of deafness (e.g., Nadol et al, 1989). Half of the participants in this study (8 of 16) were older than 60 years at the time of participation, and almost half (7 of 16) had durations of deafness longer than 10 years prior to implant (see Table 1). Collectively, the demographic factors for most of the subjects in this study would suggest some loss of peripheral processes; however, we have no clear way to measure auditory nerve survival in living humans.

Peak Location

The present study found no consistent effect of polarity on the location of the peak electrode, consistent with the hypothesis (see Fig. 4). The peak occurred at the same electrode for both polarities for slightly more than half (114/224) of the pairs of SOE functions. For the remaining pairs, there was no systematic shift in the peak of the SOE function across polarities. Physiological (e.g., Cohen et al, 2003; Abbas et al, 2004; Hughes and Stille, 2010; Undurraga et al, 2012) and perceptual (e.g., Kwon and van den Honert, 2006; Hughes and Stille, 2008; Nelson et al, 2008; Macherey et al, 2010) forward-masking functions obtained with symmetrical, cathodic-leading, biphasic pulses delivered in monopolar mode typically result in functions with a single peak at or near the location where the masker and probe are delivered to the same electrode. However, these results may have been different if polarity was manipulated. Different degrees of degeneration in the populations of neurons responding to each polarity may affect the location of the peak of the SOE function. For these reasons, we did not have a clear prediction as to whether or not polarity would have a notable effect on the location of the peak of the SOE functions. To date, no other studies have systematically evaluated the effects of stimulus polarity on forward-masking patterns for monopolar stimulation using symmetrical biphasic pulses. However, with bipolar stimulation (particularly with wide spacings), dual-peaked functions have been obtained (e.g., Chatterjee et al, 2006; Nelson et al, 2008; Zhu et al, 2012). For ECAP recordings using a wide bipolar stimulation mode (BP+9), Undurraga et al. (2012) found that the centroid of the SOE function occurred closest to the electrode delivering the anodic phase, suggesting that the anodic phase provided the most masking. Given that the present study used monopolar stimulation, it was not surprising that the peak electrode location did not change with polarity.

Area Under the Curve

Anodic-leading pulses generally produced broader SOE patterns than cathodic-leading pulses (Figs. 5 and 6). This result is consistent with the hypothesis that the anodic-leading polarity likely provides more effective masking than the cathodic polarity, and therefore larger ECAP amplitudes across the entire SOE pattern. However, it should be noted that it is difficult to determine whether greater excitation is in response to the masker, probe, or both. To fully elucidate the polarity effects of the masker and probe, polarity would need to be assessed separately for the masker and probe (e.g., anodic-leading masker with cathodic-leading and anodic-leading probes). To isolate masker polarity effects, Macherey et al. (2008) and Undurraga et al. (2010) used symmetrical biphasic pulses with long interphase gaps to effectively create a monophasic masker using the second phase of the pulse. Both studies found that ECAP responses could only be obtained in response to an anodic masker; the cathodic masker did not produce ECAPs. In some cases, the cathodic masker even appeared to produce facilitation rather than masking. With more effective masking provided by the anodic phase, larger ECAPs will result. When the forward-masking paradigm is applied, the result is a broader SOE pattern, as observed in the present study.

In contrast to the present findings, Undurraga et al. (2012) found that the width of the SOE function was not different between polarities. There are several notable stimulus differences between their study and the present study, however. First, the probe stimulus in their study was always a cathodic-leading symmetrical biphasic pulse, while the polarity and configuration (monopolar/bipolar) of the masker was varied. In our study, the masker and probe were identical stimuli, and both reversed in polarity together. Additionally, they used several different configurations of masker pulses (symmetrical biphasic in monopolar and bipolar mode; and pseudomonophasic and symmetrical biphasic with a long interphase gap in only bipolar mode), but did not report polarity effects on the SOE width for the monopolar condition (most similar to our study). Last, their results were based on data from only five subjects, whereas the present study had 16 subjects. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess polarity effects on ECAP SOE patterns using clinically relevant stimuli.

Spatial Separation

When comparing SOE patterns for two spatially separated probe electrodes, the larger, broader patterns found with anodic-leading pulses lead to greater overlap of the respective SOE patterns, and thereby yield less spatial separation between probe electrodes. Broader patterns appear to be the product of more effective masking of the neural response to the probe for anodic stimuli, likely due to stimulation of the central axon of auditory nerve fibers (e.g., Macherey et al, 2008; Undurraga et al, 2010). It is possible that the narrower SOE patterns (and thus more spatial separation) observed with cathodic-leading stimuli are due to less effective masking with the forward-masking subtraction method. If a cathodic-leading stimulus is less effective than an anodic-leading stimulus, then it would also be a less effective masker. Less effective masking would result in more neurons responding to the probe in the masked probe condition (i.e., a larger masked response). When subtracted from the probe-alone trace, the result would be a smaller ECAP than would otherwise be derived if the masker were more effective. If the raw ECAP amplitudes are smaller across the entire SOE function for the cathodic-leading condition than for the anodic-leading condition (as was demonstrated in Fig. 3), then the resulting SOE pattern for the cathodic-leading condition will likely be narrower. This effect can be seen in the inset panel in Fig. 2, which shows the larger-amplitude SOE (open circles) for anodic-leading stimuli, along with the smaller-amplitude SOE (filled circles) for cathodic-leading stimuli. The smaller overall amplitudes for the cathodic condition result in the function falling to 0 μV at masker electrodes 5 and 21 (producing a narrower SOE pattern), whereas this occurs at masker electrodes 3 and 22 for the anodic function (producing a broader SOE pattern). As a result, smaller ECAPs lead to generally narrower SOE patterns, and therefore greater spatial separation between curves is expected. As noted above, however, it is unclear whether the differences in spatial separation arise primarily from polarity effects of the masker, probe, or both.

We must also consider the effects of neural health in the context of the present results. Cochlear-implant recipients typically have severe to profound hearing loss, which tends to be accompanied by substantial degeneration or loss of peripheral processes in the auditory nerve. However, individuals with greater degrees of residual hearing are receiving CIs. The models of Rattay et al. (2001b) suggest that biphasic pulses of both polarities are equally effective in generating action potentials when peripheral processes are present. Therefore, if the SOE patterns for each leading polarity are similar, this could potentially indicate regions of greater neural survival.

Limitations and Future Directions

A general limitation of the forward-masking method used to measure the SOE pattern is that it does not differentiate between excitation due to the masker versus the probe. Instead, it exploits some degree of spatial overlap between two electrodes. Therefore, in our study, it is not possible to say that the effects of polarity on ECAP amplitude, curve area, and spatial separation are due exclusively to the masker. Rather, they are likely due to some combination of excitation from the masker and the probe. In order to elucidate effects of the masker, other experimental conditions where the masker and probe differ in polarity (e.g., masker cathodic-leading, probe anodic-leading) would need to be carried out. For symmetric biphasic pulses with long interphase gaps, Undurraga et al. (2010) found that ECAPs could only be measured when the masker was anodic-leading, regardless of whether the probe was anodic or cathodic-leading.

Two studies have proposed other methods to more accurately estimate SOE patterns. Biesheuvel et al. (2016) used a deconvolution method to separate excitation areas generated by the masker and the probe. These areas, or excitation density profiles, were highly correlated with SOE curves measured using the forward-masking method when the modeled excitation patterns were exponential or Gaussian (as opposed to rectangular). This relationship was diminished for normalized SOE curves, suggesting normalization may not be necessary for deconvolution. Cosentino et al. (2015) described a “panoramic” multistage optimization approach intended to model spread of excitation, as well as identify neural dead regions and cross-turn stimulation that could be unaccounted for in the forward-masking method. The authors compared their model to the forward-masking method for both simulated and human ECAP data. The model was found to be reliable with minimal error, as long as the signal-to-noise ratio was above 5 dB. While both reports claim to correctly model spread of excitation, future studies are needed to compare these methods against each other, as well as to assess SOE patterns obtained with anodic-leading stimuli. Perhaps a combination of anodic stimuli and improvements in the forward-masking method for measuring spread of excitation would improve the ability of the ECAP SOE to better predict electrode discrimination on the basis of pitch.

Conclusions

Results from this study show that anodic-leading, symmetrical, biphasic pulses produce larger ECAP amplitudes and broader excitation patterns compared with cathodic-leading pulses when equal CLs are used. These combined factors reduce the spatial separation between SOE functions obtained for different electrodes, and are likely a result of more effective masking. Further research is needed to determine whether the spatial separation between SOE patterns obtained with anodic-leading pulses better predicts pitch discrimination between electrodes. Our work also has implications for clinical practice. Given that anodic-leading pulses more effectively stimulate the auditory nerve, future versions of software may allow clinicians to choose this type of stimulus in coding strategies. Because less current is needed to achieve similar loudness levels to cathodic stimulation (Carlyon et al, 2013), recipients may benefit from longer battery life and reduced non-auditory perceptions if anodic-leading stimuli are used.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the NIH, NIDCD, grants R01 DC009595, T35 DC008757, and P30 DC04662. The content of this project is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIDCD or the NIH.

Abbreviations

- ECAP

electrically evoked compound action potential

- CI

cochlear implant

- CL

current level

- SOE

spread of excitation

Footnotes

Data from this study will be presented at the 2017 American Auditory Society Scientific and Technology Meeting.

Although others (e.g., Cohen et al, 2003) have used more elaborate curve-fitting methods to estimate values for the recording electrode (or other missing data points), we feel a simple interpolation is sufficient for the measures of interest here.

References

- Abbas PJ, Brown CJ, Shallop JK, Firszt JB, Hughes ML, Hong SH, Staller SJ. Summary of results using the Nucleus CI24M implant to record the electrically evoked compound action potential. Ear Hear. 1999;20:45–59. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199902000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbas PJ, Hughes ML, Brown CJ, Miller CA, South H. Channel interaction in cochlear implant users evaluated using the electrically evoked compound action potential. Audiol Neurotol. 2004;9:203–13. doi: 10.1159/000078390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesheuvel JD, Briaire JJ, Frijns JH. A novel algorithm to derive spread of excitation based on deconvolution. Ear Hear. 2016;37:572–581. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlyon RP, Deeks JM, Macherey O. Polarity effects on place pitch and loudness for three cochlear-implant designs and at different cochlear sites. J Acoust Soc Am. 2013;134:503–9. doi: 10.1121/1.4807900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee M, Galvin JJ, Fu Q-J, Shannon RV. Effects of stimulation mode, level and location on forward-masked excitation patterns in cochlear implant patients. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2005;7:15–25. doi: 10.1007/s10162-005-0019-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LT, Richardson LM, Saunders E, Cowan RSC. Spatial spread of neural excitation in cochlear implant recipients: comparison of improved ECAP method and psychophysical forward masking. Hear Res. 2003;179:72–87. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino S, Gaudrain E, Deeks JM, Carlyon RP. Multistage nonlinear optimization to recover neural activation patterns from evoked compound action potentials of cochlear implant users. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2016;63:833–40. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2015.2476373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goehring JL, Neff DL, Baudhuin JL, Hughes ML. Pitch ranking, electrode discrimination, and physiological spread-of-excitation using Cochlear’s dual-electrode mode. J Acoust Soc Am. 2014a;136:715–27. doi: 10.1121/1.4884881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goehring JL, Neff DL, Baudhuin JL, Hughes ML. Pitch ranking, electrode discrimination, and physiological spread of excitation using current steering in cochlear implants. J Acoust Soc Am. 2014b;136:3159–71. doi: 10.1121/1.4900634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinojosa R, Marion M. Histopathology of profound sensorineural deafness. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1983;405:459–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1983.tb31662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ML, Abbas PJ. The relation between electrophysiologic channel interaction and electrode pitch ranking in cochlear implant recipients. J Acoust Soc Am. 2006;119:1527–37. doi: 10.1121/1.2163273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ML, Goehring JL, Baudhuin JL. Effects of stimulus polarity and artifact reduction method on the electrically evoked compound action potential. Ear Hear. 2017 doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ML, Stille LJ, Baudhuin JL, Goehring JL. ECAP spread of excitation with virtual channels and physical electrodes. Hear Res. 2013;306:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ML, Stille LJ. Effect of stimulus and recording parameters on spatial spread of excitation and masking patterns obtained with the electrically evoked compound action potential in cochlear implants. Ear Hear. 2010;31:679–92. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181e1d19e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ML. A re-evaluation of the relation between physiological channel interaction and electrode pitch ranking in cochlear implants. J Acoust Soc Am. 2008;124:2711–4. doi: 10.1121/1.2990710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano A, Raine C, Seldon H, Clark G, Ramsden R. Intracochlear factors contributing to psychophysical percepts following cochlear implantation. Acta Otolaryngol. 1998;118:313–26. doi: 10.1080/00016489850183386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AM, Whiten DM, Nadol J, Joseph B, Eddington DK. Histopathology of human cochlear implants: Correlation of psychophysical and anatomical measures. Hear Res. 2005;205:83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klop WMC, Hartlooper A, Briaire JJ, Frijns JHM. A new method for dealing with the stimulus artefact in electrically evoked compound action potential measurements. Acta Otolaryngol. 2004;124:137–43. doi: 10.1080/00016480310016901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon BJ, van den Honert C. Effect of electrode configuration on psychophysical forward masking in cochlear implant listeners. J Acoust Soc Am. 2006;119:2994–3002. doi: 10.1121/1.2184128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macherey O, Carlyon RP, van Wieringen A, Deeks JM, Wouters J. Higher sensitivity of human auditory nerve fibers to positive electrical currents. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2008;9:241–51. doi: 10.1007/s10162-008-0112-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macherey O, Carlyon RP. Place-pitch manipulations with cochlear implants. J Acoust Soc Am. 2012;131:2225–36. doi: 10.1121/1.3677260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macherey O, Deeks JM, Carlyon RP. Extending the limits of place and temporal pitch perception in cochlear implant users. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2011;12:233–51. doi: 10.1007/s10162-010-0248-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macherey O, van Wieringen A, Carlyon RP, Dhooge I, Wouters J. Forward-masking patterns produced by symmetric and asymmetric pulse shapes in electric hearing. J Acoust Soc Am. 2010;127:326–38. doi: 10.1121/1.3257231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CA, Abbas PJ, Robinson BK, Rubinstein JT, Matsuoka AJ. Electrically evoked single-fiber action potentials from cat: responses to monopolar, monophasic stimulation. Hear Res. 1999;130:197–218. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CA, Abbas PJ, Rubinstein JT, Robinson BK, Matsuoka AJ, Woodworth G. Electrically evoked compound action potentials of guinea pig and cat: responses to monopolar, monophasic stimulation. Hear Res. 1998;119:142–54. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadol JB, Young YS, Glynn RJ. Survival of spiral ganglion cells in profound sensorineural hearing loss: implications for cochlear implantation. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1989;98:411–6. doi: 10.1177/000348948909800602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadol JB, Burgess BJ, Gantz BJ, Coker NJ, Ketten DR, Kos I, et al. Histopathology of cochlear implants in humans. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110:883–91. doi: 10.1177/000348940111000914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadol JB. Patterns of neural degeneration in the human cochlea and auditory nerve: Implications for cochlear implantation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:220–8. doi: 10.1016/s0194-5998(97)70178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DA, Donaldson GS, Kreft H. Forward-masked spatial tuning curves in cochlear implant users. J Acoust Soc Am. 2008;123:1522–43. doi: 10.1121/1.2836786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng M, Niparko JK, Nager GT. Cochlear implants: principles and practices. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2000. Inner ear pathology in severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss; pp. 57–100. [Google Scholar]

- Rattay F, Lutter P, Felix H. A model of the electrically excited human cochlear neuron: I. Contribution of neural substructures to the generation and propagation of spikes. Hear Res. 2001a;153:43–63. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattay F, Leao RN, Felix H. A model of the electrically excited human cochlear neuron. II. Influence of the three-dimensional cochlear structure on neural excitability. Hear Res. 2001b;153:64–79. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00257-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders E, Cohen L, Aschendorff A, Shapiro W, Knight M, Stecker M, et al. Threshold, comfortable level and impedance changes as a function of electrode-modiolar distance. Ear Hear. 2002;23:28S–40S. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200202001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undurraga JA, Carlyon RP, Macherey O, Wouters J, van Wieringen A. Spread of excitation varies for different electrical pulse shapes and stimulation modes in cochlear implants. Hear Res. 2012;290:21–36. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undurraga JA, Carlyon RP, Wouters J, van Wieringen A. The polarity sensitivity of the electrically stimulated human auditory nerve measured at the level of the brainstem. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2013;14:359–77. doi: 10.1007/s10162-013-0377-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undurraga JA, van Wieringen A, Carlyon RP, Macherey O, Wouters J. Polarity effects on neural responses of the electrically stimulated auditory nerve at different cochlear sites. Hear Res. 2010;269:146–61. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z, Tang Q, Zeng F-G, Guan T, Ye D. Cochlear-implant spatial selectivity with monopolar, bipolar and tripolar stimulation. Hear Res. 2012;283:45–58. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]