Research over the past three decades has established that loss of cardiomyocytes through regulated cell suicide mechanisms contributes critically to the pathogenesis of myocardial infarction, heart failure, and other cardiac syndromes1. Two of the most important cell death programs in the context of heart disease are apoptosis and necrosis. These forms of cell death differ primarily with respect to the magnitude of collateral damage inflicted on surrounding tissue. In apoptosis, the plasma membrane remains intact until the dying cell undergoes phagocytosis, while in necrosis not only does the membrane become leaky but the cell actively secretes proinflammatory molecules. Apoptosis has always been recognized as a gene-directed and regulated process. In contrast, necrosis was thought to be an uncontrolled form of cell death resulting from overwhelming physical and chemical trauma to a cell. A big surprise over the past 15 years, however, has been the realization that a significant proportion of necrotic cell deaths occurs through highly regulated mechanisms.

Both apoptosis and necrosis can be initiated through two major pathways: one involving mitochondria and the other cell surface death receptors (Figure, panel A). In this issue of Circulation, Guo et al utilize multiple mouse genetic models to dissect the death receptor pathway in the heart2. The most important finding in this study is that knockout of the gene encoding tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2), a protein in this pathway, results in dilated cardiomyopathy through unleashing apoptotic and necrotic cardiomyocyte death.

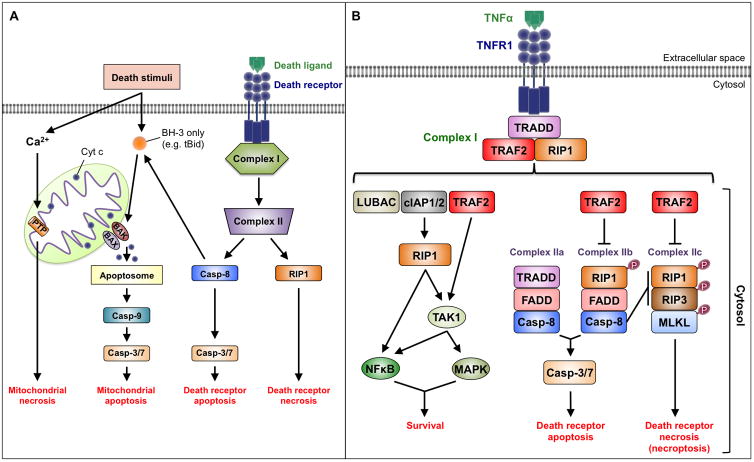

Figure. Apoptosis and Necrosis Signaling.

A. Overview. Both apoptosis and necrosis can be initiated through death receptor and mitochondrial pathways. Regardless of pathway, the defining molecular event in apoptosis is activation of caspases, which are a class of cysteine proteases. Caspase activation takes place in complex IIa and complex IIb in the death receptor pathway (see panel B) and the apoptosome in the mitochondrial pathway. Apoptosome assembly is triggered by cytochrome c, which is released through permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane. The defining events in necrosis involve activation of receptor interacting proteins 1 and 3 (RIP1 and RIP3), which are kinases, in the death receptor pathway, and opening of the inner mitochondrial membrane permeability transition pore (PTP) in the mitochondrial pathway.

B. Death receptor signaling. The binding of TNF-α to TNFR1 stimulates the assembly of Complex I, which signals cell survival. This complex includes the adaptor protein TRADD, the kinase referred to as receptor interacting protein 1 (RIP1), and several E3-ubiquitin ligases. The addition of amino to carboxyl-linked ubiquitin chains onto RIP1 by linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LUBAC) provides a platform for the activation of the transcription factor NF-κB. The attachment of lysine 63-linked ubiquitin chains to RIP1 by cellular inhibitor of apoptosis proteins 1 and 2 (cIAP1 and 2) and TRAF2 provides a platform for the activation of TAK1, which in turn activates NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs). TAK1 may also be activated more directly through TRAF2-mediated ubiquitylation. De-ubiquitylation of RIP1 leads to disassembly of Complex I and formation several cytoplasmic complexes. Complex IIa includes TRADD, Fas-associated death domain (FADD), and procaspase-8 - the result being caspase activation and apoptosis. Complex IIb (the “ripoptosome”), involving RIP1, FADD, and procaspase-8, also induces apoptosis but through RIP1 phosphorylation. In addition, caspase-8 activation inhibits necroptosis by cleaving RIP1 and RIP3. If caspase-8 is inhibited, however, Complex IIc (the “necrosome”) may form, which signals necroptosis through the phosphorylation and interaction of RIP1 and RIP3. Events that mediate necroptosis downstream of RIP3 include: (a) phosphorylation and recruitment of MLKL, which oligomermizes to cause plasma membrane dysfunction; (b) activation of metabolic enzymes that generate oxidative stress; and (c) activation of Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-delta (CaMKII-δ) leading to opening of the inner mitochondrial membrane permeability transition pore.

The death receptor pathway is initiated by various ligands of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family3. The present study focuses on binding of TNF-α to TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1). Depending on other signals and conditions in the cell, this may promote cell survival, apoptosis, or a regulated form of necrosis, which in this pathway is referred to as “necroptosis” (Figure, panel B). Cell survival is stimulated by TNF-α-induced recruitment of proteins into Complex I at the plasma membrane. Complex I, however, can morph into several cytoplasmic protein complexes including Complexes IIa and IIb that induce apoptosis, and Complex IIc that signals necroptosis. The molecular regulation of these transitions is incompletely understood, but de-ubiquitylation plays an important role in the disassembly of Complex I and loss of cell survival signals. A major factor in the choice of necroptotic over apoptotic cell death is the inhibition of caspases, which are proteases required for apoptosis. Molecular details regarding the death receptor pathway are provided in the figure legend.

Guo et al used multiple genetic mouse models, cultured mouse embryonic fibroblasts, and primary cardiomyocytes to define the role of TRAF2, an E3-ubiquitin ligase, in the heart. The data show that myocardial TRAF2 levels increase significantly in response to various cardiac stresses (e.g. pressure overload and post-myocardial infarction). Strikingly, cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of TRAF2 elicits a severe dilated cardiomyopathy even in the absence of superimposed cardiac stress. This is characterized by apoptosis (likely through Complex IIb because it is sensitive to RIP1 kinase inhibition) and necroptosis. The rest of the paper addresses mechanism (Figure). Not surprisingly, given its upstream role in Complex I, TNF receptor-associated death domain (TRADD) is important in cardiomyocyte apoptosis and necroptosis, as is the E3-ligase function of TRAF2. Interestingly, the study shows that increased plasma TNF-α levels observed with cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of TRAF2 exacerbate heart failure as simultaneous deletion of TNFR1 partially rescues the phenotype. Although transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) activation suffices to attenuate both apoptotic and necroptotic events, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) unexpectedly appears dispensable in this system. Both receptor interacting protein 3 (RIP3) and mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) were shown to be important in TNF-α-induced cardiomyocyte necroptosis, which is notable as MLKL appears dispensable for necroptosis in some other cardiac paradigms4. Finally, in addition to the canonical induction of necroptosis resulting from caspase inhibition that defines the TNF-α pathway, the study revealed some interesting crosstalk whereby inhibition of necroptosis amplifies apoptosis.

The major challenge not addressed by this work is the molecular nature of the connections by which TRAF2 suppresses apoptosis and necroptosis. The study does provide the important hint that the TRAF2 E3-ubiquitin ligase function is required, and clearly RIP1 and TAK1, both of which are TRAF2 substrates5, 6, are good candidates to mediate the observed survival effects. But, the mechanism may not be this simple as other E3-ligases in Complex I can also ubiquitylate these proteins. This raises the question as to whether additional TRAF2 ubiquitylation targets are involved. Accordingly, it might be informative to more broadly define the proteome modified by TRAF2, as has been accomplished for other E3-ligases7. In addition, the possibility exists that TRAF2 may suppress cell death indirectly through its participation in other processes such as its recently demonstrated role in mitophagy, which is also dependent on its E3-ligase function8.

What is the relevance of these findings to the pathogenesis of heart failure? The dilated cardiomyopathy resulting from deletion of TRAF2 in cardiomyocytes underscores the importance of this protein in maintaining baseline cardiac structure and function. The observation that TRAF2 abundance increases in response to pathological stimuli suggests that this protein also protects the heart against stress. More generally, this study demonstrates that death receptor signaling results in a complex interplay of activating and inhibitory effects on adverse cardiac remodeling, thereby extending previous investigations into the role of this pathway in heart disease4, 9–11.

Can the death receptor pathway be manipulated to therapeutic advantage in heart failure using small molecule drug approaches? While activation of the survival arm may not currently be in reach, a number of RIP1 and RIP3 inhibitors developed for other purposes may serve to inhibit necroptosis in heart failure and, based on other data, also in ischemic injury3. While these approaches merit exploration, several caveats need to be considered. First, reciprocal activation of other death programs (e.g. mitochondrial death pathway, Figure, panel A) may necessitate a combined pharmacological approach. Second, the use of cell death inhibition in any chronic setting - including heart failure - must be balanced against potential untoward effects (e.g. cancer).

In conclusion, this study provides an important new piece in understanding the role of cell death in heart disease. With a more complete molecular understanding, this pathway may be targeted therapeutically to protect the heart during the most common and lethal cardiac syndromes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Lorenzo Galluzzi for critical comments.

Sources of Funding

Support was provided for DA by an American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship (15PRE25080032); for YC by an American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant (17SDG33410907); and for RNK by grants from NIH (R01HL128071, R01HL130861, R01CA17091), Department of Defense (PR151134P1), American Heart Association (15CSA26240000), Fondation Leducq (RA15CVD04), the Dr. Gerald and Myra Dorros Chair in Cardiovascular Disease, and the Wilf Family.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

None

References

- 1.Konstantinidis K, Whelan RS, Kitsis RN. Mechanisms of cell death in heart disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:1552–62. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.224915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo X, Yin H, Li L, Chen Y, Li J, Doan J, Steinmetz RN, Liu Q. Cardioprotective Role of TRAF2 by Suppressing Apoptosis and Necroptosis. Circulation. 2017 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conrad M, Angeli JP, Vandenabeele P, Stockwell BR. Regulated necrosis: disease relevance and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15:348–66. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2015.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang T, Zhang Y, Cui M, Jin L, Wang Y, Lv F, Liu Y, Zheng W, Shang H, Zhang J, Zhang M, Wu H, Guo J, Zhang X, Hu X, Cao CM, Xiao RP. CaMKII is a RIP3 substrate mediating ischemia- and oxidative stress-induced myocardial necroptosis. Nat Med. 2016;22:175–82. doi: 10.1038/nm.4017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang L, Blackwell K, Shi Z, Habelhah H. The RING domain of TRAF2 plays an essential role in the inhibition of TNFalpha-induced cell death but not in the activation of NF-kappaB. J Mol Biol. 2010;396:528–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan Y, Yu Y, Shi Y, Sun W, Xie M, Ge N, Mao R, Chang A, Xu G, Schneider MD, Zhang H, Fu S, Qin J, Yang J. Lysine 63-linked polyubiquitination of TAK1 at lysine 158 is required for tumor necrosis factor alpha- and interleukin-1beta-induced IKK/NF-kappaB and JNK/AP-1 activation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:5347–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.076976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarraf SA, Raman M, Guarani-Pereira V, Sowa ME, Huttlin EL, Gygi SP, Harper JW. Landscape of the PARKIN-dependent ubiquitylome in response to mitochondrial depolarization. Nature. 2013;496:372–6. doi: 10.1038/nature12043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang KC, Ma X, Liu H, Murphy J, Barger PM, Mann DL, Diwan A. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 2 mediates mitochondrial autophagy. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:175–87. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burchfield JS, Dong JW, Sakata Y, Gao F, Tzeng HP, Topkara VK, Entman ML, Sivasubramanian N, Mann DL. The cytoprotective effects of tumor necrosis factor are conveyed through tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 2 in the heart. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3:157–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.899732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luedde M, Lutz M, Carter N, Sosna J, Jacoby C, Vucur M, Gautheron J, Roderburg C, Borg N, Reisinger F, Hippe HJ, Linkermann A, Wolf MJ, Rose-John S, Lullmann-Rauch R, Adam D, Flogel U, Heikenwalder M, Luedde T, Frey N. RIP3, a kinase promoting necroptotic cell death, mediates adverse remodelling after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;103:206–16. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee P, Sata M, Lefer DJ, Factor SM, Walsh K, Kitsis RN. Fas pathway is a critical mediator of cardiac myocyte death and MI during ischemia-reperfusion in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H456–63. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00777.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]