Abstract

Objective

To estimate the cost of dementia and the extra cost of caring for someone with dementia compared to someone without dementia.

Design

We developed an evidence-based mathematical model to simulate disease progression for newly diagnosed individuals with dementia. Data driven trajectories of cognition, function, and behavioral/psychological symptoms were used to model disease progression and predict costs. Using modeling, we evaluated lifetime and annual costs among those with dementia, compared costs between those with and without dementia clinical features, and evaluated the effect of reducing functional decline or behavioral/psychological symptoms by 10% for 12 months (implemented when Mini-Mental State Examination≤21).

Setting

Mathematical model.

Participants

Representative simulated US incident dementia cases.

Measurements

Value of informal care, out-of-pocket expenditures, Medicaid expenditures, and Medicare expenditures.

Results

From time of diagnosis (mean age of 83 years) discounted total lifetime cost of care for a person with dementia was $321,780 (2015 dollars). Families incurred 70% of the total cost burden ($225,140). Medicaid accounted for 14% ($44,090) and Medicare accounted for 16% ($52,540) of total cost, respectively. Costs for a person with dementia over a lifetime were $184,500 greater (86% incurred by families) than for someone without dementia. Total annual cost peaked at $89,000 and net cost peaked at $72,400. Compared to natural disease progression, reducing functional decline or behavioral/psychological symptoms by 10% resulted in $3,880 and $680 lower lifetime costs, respectively.

Conclusion

Dementia substantially increases the lifetime costs of care. Long lasting effective interventions are needed to support families as they incur the most dementia cost.

Keywords: dementia, family caregiving, institutionalization, dementia cost

INTRODUCTION

More than 5 million Americans live with dementia.1 As the population ages, this number will increase placing an even greater burden on families, the long-term care system, and the economy.1 The societal economic burden of dementia consists of different types of costs (value of informal care, out-of-pocket expenditures, Medicaid expenditures, and Medicare expenditures), and several payers (family, Medicaid, and Medicare) bear various amounts of the economic responsibility. To facilitate planning at the family, state, and federal levels policymakers must better understand who incurs dementia costs over the life course of the disease.2

Two recent studies highlight the economic burden of the disease over short periods of time. One found that in the last five years of life, a person with dementia receives >$250,000 worth of care.3 The other found that those with dementia receive >$56,000 in additional care in any given year compared to those without dementia.4 In both studies, families incurred the greatest cost burden due to informal caregiving and out-of-pocket payments for formal long-term care services. However, neither study accounted for the dynamic processes and substantial variations that occur in symptom presentation (cognitive and functional decline and behavioral/psychological symptoms of dementia) over the course of dementia.

We estimated the total lifetime and annual costs of dementia care and the extra cost of caring for someone with dementia compared to someone without dementia (net cost) using a comprehensive US dementia microsimulation model. Our model overcomes the limitations of previous dementia simulation models by synthesizing data from a clinical registry, a nationally representative survey, and CMS Medicare data to model cognitive, functional, and behavioral/psychological trajectories and associated resource utilization.

METHODS

Model Design

Our evidence-based individual-level model simulated a newly diagnosed dementia patient’s disease progression (cognition, function, and behavioral/psychological symptoms), place of residence (community or long-term care facility), and Medicaid status (i.e., dual enrollment), to estimate the lifetime and the full range of annual costs of care.

Specifically, an individual entered the model as a community-dwelling incident case. At the point of entry (i.e., diagnosis of dementia), and prior to disease progression, the person with dementia’s personal characteristics (e.g., age) and the characteristics of a primary caregiver were randomly generated from published incident statistics or derived from observational data (data sources described below; Supplementary Table S1 details the baseline characteristics).5,6 This allowed the simulated population to be as representative as possible of the general population. As described in detail below, when the person with dementia aged (i.e., progressed through the model in monthly increments), their cognition, function, and behavioral/psychological symptoms (i.e., clinical features) changed and they could experience transitions between places of residence, transitions from Medicare-only to dual enrollment, and death due to dementia or other causes.7–10 Personal characteristics, the clinical features, place of residence, and insurance status, were used to predict costs.

Measures of Disease Progression: Cognition, Function, and Behavioral/Psychological Symptoms

Dementia progression was modeled using three key clinical features -cognition, function, and behavioral/psychological symptoms.11 Cognition was modeled using the Mini-Mental State Examination, which is scored from 0–30 with lower scores indicating greater cognitive impairment.12 Function was modeled as the number of 10 functional limitations present and is scored from 0–10 with higher scores indicating more limitations (Supplementary Table S2). Behavioral/psychological symptoms were modeled as the number of 12 symptoms present based on symptoms in the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire version Q (Supplementary Table S3). These measures of the clinical features were chosen as they are consistent with the measures available in the data used to predict clinical trajectories, transitions in place of residence, and cost (prediction equations described below).13–15

Modeling Disease Progression

To model disease progression over time, we adapted previously developed cognitive, functional, and behavioral/psychological mixed effect regression trajectory models of incident dementia cases (Table 1).13 These models used longitudinal data from the Uniform Data Set of the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center, which contains data from 34 Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADCs), to estimate separate trajectories of the three clinical features over time.6 During annual assessments, trained ADC providers administered a standardized protocol that included cognitive, functional, and behavioral/psychological assessments. The trajectory models included explanatory variables believed to be risk factors of disease onset and decline (Supplementary Table S4–S6 report model coefficients for each trajectory model).

Table 1.

Dementia Policy Model Structure and Inputs

| Step 1: Disease Progression | ||

|

| ||

| Model Parameter | Description | Data Source |

|

Linear mixed effects models directly estimated from data (Supplementary Table S4) | National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center6,13 |

|

| ||

| Step 2: Care Transitions | ||

|

| ||

| Model Parameter | Description | Data Source |

|

Weibull survival model directly estimated from data (Supplementary Table S7) | National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center6 |

|

0–90 days = 0.13 90–180 days = 0.009 180–365 days = 0.003 |

Arling et al.17 |

|

community-dwelling = 0.00206residing in long-term care facility = 0.01056 | Lim et al. and Spillman et al.18,19 |

|

| ||

| Step 3: Time Spent Caregiving and Expenditures | ||

|

| ||

| Model Parameter | Description | Data Source |

|

Regression model from literature | Jutkowitz et al.14 |

|

Regression model directly estimated from data (Supplementary Table S8) | Aging, Demographics and Memory Study5 |

|

Regression model from literature | Jutkowitz et al.15 |

|

Regression model from literature | Jutkowitz et al.14 |

|

private pay = $7,270/month Medicaid pay = $6,236/month |

MetLife and American Health Care Association22,24 |

|

$900/month | Garfield et al. and Bharmal et al.25,26 |

|

| ||

| Step 4: Mortality | ||

|

| ||

| Model Parameter | Model Estimate/Estimation Method | Data Source |

|

Age-, sex-, and race-mortality rates and dementia specific hazard rate | US life tables and Brookmeyer et al.7,20 |

Notes: Persons with dementia were individually simulated. At point of entry (i.e., diagnosis) the model generated the characteristics of the person with dementia (age, gender, education, race, marital status, region of residence, insurance status, household income, number of children, comorbidities) and characteristics of the primary caregiver (if the caregiver lives with the person with dementia, and the relationship between the person with dementia and caregiver). During each monthly cycle an individual’s cognitive and functional abilities and number of behavioral and psychological symptoms were determined (Step 1). The clinical features and personal characteristics were used to determine transitions (Step 2). Personal characteristics, the clinical features, place of residence, and insurance status, were used to estimate cost of care (Step 3). If an individual was predicted to survive (Step 4) the cycle, then they repeated Steps 1–4. If they were predicted to die, then they exited the model.

Models the risk of long-term care facility admissions excluding admissions for Medicare covered skilled nursing care.

If a person with dementia did not leave the long-term care facility within a year it was assumed they remained in the facility for life.

Once an individual was dual-eligible it was assumed they would enroll in Medicaid and remain on Medicaid for life. Background Medicaid transition risk for community-dwelling individuals without dementia was 0.0008. Individuals with dementia had an excess transition risk (hazard ratio 2.575). All individuals residing in a facility had a 0.0085 added Medicaid transition risk.

Medicaid expenditures for those with dementia residing in the community. In counterfactual analyses Medicaid expenditures for those without dementia were $810.

Transitions Between Place of Residence, Medicare-only to Dual Enrollment, and Death

Risk of transitioning to a long-term care facility was modeled using the Uniform Data Set. These long-term care admissions were assumed to be independent of Medicare-covered skilled nursing admissions as our estimates of Medicare expenditures (described below) included those for skilled nursing care. This assumption is supported by the few observed transitions in the data of individuals moving from the facility back to the community indicating that most of the long-term care admissions were likely for non-Medicare covered care. To model long-term care admissions, we developed a parametric survival model to enable extrapolation beyond the available data and to predict the absolute risk of being institutionalized. We chose to use a Weibull survival model compared to an exponential or Gompertz models based on visual inspection of the hazard functions, and because the Weibull model had the lowest Akaike Information Criterion.16 Our long-term care facility risk model included lagged terms for the clinical features and potential confounders (Table 1; Supplementary Table S7 reports Weibull model coefficients).

Although individuals can transition from a long-term care facility to the community, as noted above few such transitions occurred in the Uniform Data Set. We used published estimates of long-term care facility discharge rates to model transition back to the community (Table 1).17

For persons with dementia not dually enrolled at disease onset, the risk of transitioning to Medicare-Medicaid varied by place of residence. Individuals in the community had a lower monthly risk (0.00206) of transitioning to Medicare-Medicaid compared to those in a long-term care facility (0.01056)(Table 1).18,19 Individuals with dementia who transitioned from a long-term care facility to the community continued to face an increased Medicare-Medicaid risk for six months.

Mortality was modeled using background age-, sex-, and race- mortality rates obtained from US life tables.10 We then used a generalized reduced gradient method to calibrate age-, sex-, and race- specific hazard ratios to match published median dementia survival times based on age of disease onset (≤75, 76 – 80, 81 – 85, > 85).7,20

Costs and Time Spent Caregiving

We used published regression equations based on data from the nationally representative Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study,5 a subsample of the Health and Retirement Study21 and linked to CMS Medicare data, to predict monthly hours spent receiving informal care, monthly out-of-pocket medical expenditures and monthly Medicare expenditures.14,15 Using the same data, we estimated a regression equation to predict monthly hours spent receiving formal community based caregiving (Table 1; Supplementary Table S8 report model coefficient for formal community based caregiving). All the regression models included main effects for the clinical features, potential confounding variables, and were estimated using the sampling weights in the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study.

The value of informal caregiving was $19.71/hour (weighted average of informal caregiving of $22.26/hour for those <65 years and $14.76/hour for those ≥65 years), and the value of formal caregiving was $23/hour.22,23 We multiplied predicted monthly hours of informal and formal caregiving by the value of the care. In our base-case, approximately 11.7 hours of informal caregiving a day ($19.71/hour) is equivalent to the daily private nursing home pay rate ($231/day)(Table 1).

To model long-term care facility expenditures, we multiplied time spent in the facility by the daily pay rate taking into account differences in pay rate for private pay and Medicaid covered individuals (Table 1).22,24 Finally, Medicaid expenditures for those in the community were $900/month.25,26 Costs were discounted by 3% annually over an individual’s lifetime following a diagnosis of dementia and are reported in 2015 dollars.

Statistical Analysis

In the base-case analysis we simulated individual incident dementia cases to estimate mean lifetime and annual (conditional on surviving the entire year) total cost of care (value of informal care, Medicaid expenditures, Medicare expenditures, and individual out-of-pocket expenditures [medical care, long-term care, and formal care]), and the distribution of lifetime and annual cost by component.

We conducted a counterfactual analysis to determine what would have happened to the same simulated person had they not experienced any cognitive deficits, functional limitations, behavioral/psychological symptoms, an excess Medicaid transition risk, or excess mortality due to dementia. We then compared expected costs between the simulated person with dementia and their counterfactual dementia free version (i.e., net cost). We also conducted a series of counterfactual analyses to determine the extra cost of caring for someone with dementia compared to individuals with 1, 3 and 5 functional limitations and no cognitive deficits, no behavioral/psychological symptoms, and no excess Medicaid or mortality risk due to dementia.

Policymakers need a framework to be able to estimate the potential economic impact of policies/interventions that support individuals with dementia.2 To that end, we demonstrated the application of the model as a tool to evaluate the effects of interventions that can alter the trajectory of functional declines or behavioral/psychological symptoms. Specifically, we used the model to evaluate what would happen if an intervention were introduced that reduced functional decline by 10% or reduced the increase in number of behavioral/psychological symptoms by 10%. In this analysis, we assumed the hypothetical intervention was implemented during the early stage of the disease (MMSE ≤21) and that treatment effects lasted for 12 months. After 12 months individuals experienced the same trajectories as those in the base-case.

Sub-analyses were performed to determine outcomes by age of dementia onset (75 and 90). A second set of sub-analyses were performed to evaluate results assuming different values of informal care (base-case = $19.71/hour; low value = $10/hour; high value $28/hour).

The preferred method for evaluating uncertainty is to conduct a probabilistic sensitivity analysis.27,28 However, we estimated that >100 million iterations in the probabilistic sensitivity analysis would be needed to achieve convergence, and this was not feasible given our computational resources. Therefore, to assess the effect of uncertainty on the cost of dementia we evaluated outcomes when select parameters were set to their best/worst case values (Supplementary Table S9 details parameters varied in best/worst case sensitivity analysis).

The model was programed in TreeAge Pro 2016 and a deterministic version of the model was validated in Microsoft Excel 2011. Output from the model was analyzed in Stata version 12.

RESULTS

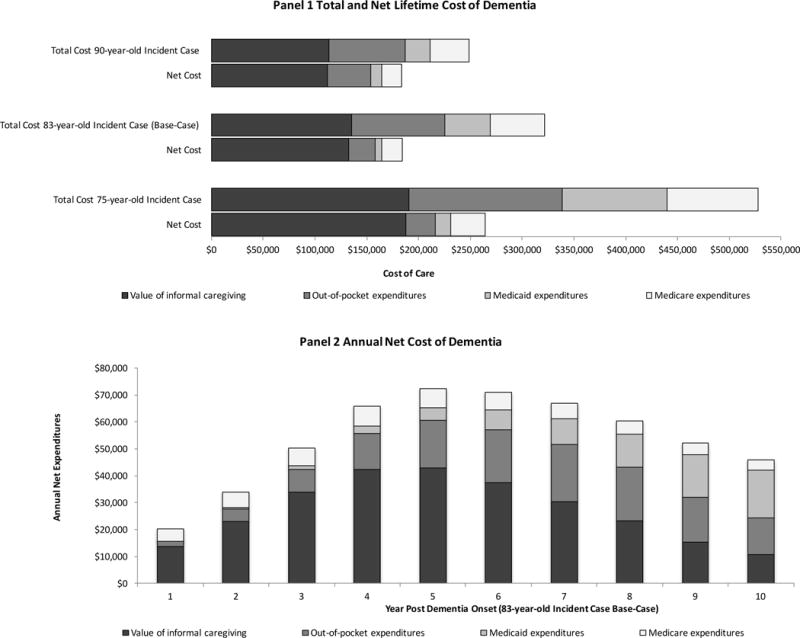

From the time of diagnosis (base-case mean age 83 years and life expectancy 60 months; Supplementary Figure S1 reports distribution of survival time by place of residence and insurance status), mean discounted lifetime total value of care was $321,780 per person with dementia (Figure 1 Panel A). Families incurred 70% of the total cost burden ($135,300, in the value of informal care and $89,840 in cash out-of-pocket payments). Medicaid payments ($44,090) accounted for 14% of total cost and Medicare payments ($52,540) accounted for 16% of total cost. The annual total cost of dementia was not constant and peaked at five years ($89,900) post dementia onset (Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 1. Distribution of Expected Total and Annual Cost.

Panel A: Discounted average total and net lifetime cost of dementia by cost type. The value of informal caregiving is $19.71/hour. Out-of-pocket expenditures include those for medical care, long-term care facility, and formal caregiving. The length of the bar is equal to average lifetime expenditures. Net cost represents the difference in expenditures between dementia cases and counterfactual dementia free cases. Panel B: Discounted average annual net cost of dementia by cost type for an 83-year-old incident case (base-case). Annual costs are calculated for those conditional on surviving the entire year.

In counterfactual analysis, someone without dementia incurred $137,280 in expenditures. Thus, an individual with dementia experienced $184,500 more cost over a lifetime than someone without dementia (Figure 1 Panel A). Families shouldered the largest net cost burden (86% of net cost incurred by all parties) due to excess informal caregiving ($132,850 more caregiving received) and out-of-pocket payments ($25,110 more out-of-pocket spending). Medicaid ($6,640) and Medicare ($19,890) payments accounted for 4% and 11% of net dementia cost, respectively. The annual net cost of dementia peaked in the fifth year post dementia onset at $72,400 (Figure 1 Panel B). Compared to individuals with 1, 3 and 5 functional limitations (but no cognitive limitations or behavioral/psychological symptoms) an individual with dementia received $168,990, $130,510, and $70,670 more care over a lifetime, respectively (Supplementary Table S10).

Finally, a hypothetical intervention (implemented when MMSE ≤21 and with a 12 month treatment effect) that reduced the rate of functional decline by 10% resulted in $3,880 less lifetime cost than someone who received usual dementia care (Supplementary Table S10). An intervention that reduced the number of behavioral/psychological symptoms by 10% resulted in $680 less lifetime cost.

In sub-analyses, the mean total (net) value of care for a 75-year-old incident case was $527,920 ($264,390). A 90-year-old dementia incident case incurred $248,980 (net $183,680) worth of care. When just the value of informal care was set to the low estimate ($10/hour) the total (net) cost of dementia was $255,120 ($119,050). Conversely, when just the value of informal care was set to the high estimate ($28/hour) the total (net) cost of dementia was $378,690 ($240,370). Finally, the total (net) cost of dementia in the best and worst case analyses was $214,700 ($111,500) and $420,850 ($242,500), respectively (Supplementary Figure S3).

DISCUSSION

The economic burden of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias and who pays such costs over the course of these conditions are of great policy relevance but cannot be directly estimated from existing data. We present a novel dementia policy model that synthesized data from a clinical registry, a nationally representative survey, and CMS Medicare data to model dementia clinical features, living arrangements, and insurance status over the life expectancy of an individual with dementia to inform policymakers of dementia cost. We found that total and net cost of dementia over a lifetime of dementia was $321,780 and $184,500, respectively.

Our evaluation of the annual net cost of dementia revealed that total cost increased for the first five years post onset and then began to slowly decrease. At the same time, out-of-pocket and Medicaid expenditures increased with time. In the early years following dementia onset, individuals in our model resided in the community. During this period, the amount of informal caregiving increased leading to greater cost. Eventually, individuals in the model began entering long-term care facilities. This resulted in an increase in net out-of-pocket and Medicaid expenditures, but on average this increase was less than the value of the substituted informal care (11.7 hours of informal care valued at $19.71 hour is equivalent to daily nursing home private pay rate of $231). Simultaneously, costs in the dementia free (counterfactual) individuals were increasing over time. The shift in locus of care combined with increasing cost in the counterfactual resulted in reduced cumulative net expenditures.

Our results highlight how the financial burden of dementia varies based on the payer. How/who pays for cost over time change from being attributable to informal care to out-of-pocket and Medicaid payments. At all times families incur the largest financial burden highlighting the importance and value of informal caregiving for individuals with dementia.29,30 From a government budgetary perspective informal caregiving is often viewed as a free or low-cost source of care. Yet, there are potentially unintended long-term consequences for caregivers (e.g., long-term health consequences).31 Moreover, demographic trends indicate the potential number of family caregivers available to provide such care to persons with dementia may decrease considerably in the upcoming decades.29,30

There is continued enthusiasm from policymakers to implement policies and interventions that reduce long-term care facility admissions and length of stay.32–34 With reductions in long-term care facility utilization (and perhaps acute/rehabilitative care as well), informal caregivers will be relied upon to shoulder even more care. If policymakers are going to continue to rely on informal caregivers, then they should provide them with effective and proven support.30 Effective long-term care policy should promote high quality care (e.g., family-centered models that include rich sources of community-based support). Sometimes high quality care costs more, but such costs largely rely on the perspective of the payer.

A review of model inputs indicates that reductions in all costs can be generated from proven interventions that alter functional and behavioral/psychological symptom trajectories, but the magnitude of savings will depend on effect sizes and their duration. For example, clinical trials of non-drug interventions have reported reductions in functional decline and the number of behavioral/psychological symptoms, but trials have reported limited economic outcomes (e.g., time in a nursing home).35–40 Future studies can use our model to connect the clinical benefits of proven interventions with economic outcomes. Our evaluation of hypothetical treatments found that reducing the rate of functional decline or number of behavioral/psychological symptoms by 10% for 12 months (implemented when Mini-Mental State Examination≤21) reduced lifetime costs by $3,880 and $680, respectively. These savings are small relative to the total disease burden, but they still may represent important savings depending on the perspective of the payer.

Although we approach the modeling of dementia cost differently, we derive similar estimates to others in the literature for annual net cost supporting the validity of our model.3,4,41 For example, from the third to tenth year, annual net costs in our model fall within the confidence interval of the net cross-sectional cost of dementia reported by the RAND study (values in RAND analysis updated to 2015 dollars for comparison with our results $64,750 95% CI: $49,170, $80,330).4 We extend results from prior studies by modeling disease progression from incidence to death.42–45 Most importantly, our dementia policy model serves as a flexible tool to evaluate treatments and their effects on policy-relevant outcomes that are not normally captured in randomized trials.

Our study has several limitations. Due to limited data, our estimates of the cost of dementia do not take into account the long-term health consequences of caregiving. Our simulation model uses several risk equations each with a number of parameters. If parameters are incorrectly specified in the original risk equations, then our predicted values may be biased. At times the simulation model may extrapolate beyond the original data and this may result in unrepresentative predictive values. Despite these potential limitations, our results of annual net cost from the second to tenth year match those of the RAND study.

In conclusion, individuals with dementia receive $321,780 worth of total care over the course of the disease, which equates to $184,500 more than if they did not have dementia. The majority of the total and net costs are borne by families for informal care and out-of-pocket payments. Policy and services should be implemented to support family members in the community.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table S1 Baseline Demographic Characteristics

Supplementary Table S2 Functional Domains

Supplementary Table S3 Behavioral and Psychological Symptom Domains

Supplementary Table S4 Linear Mixed Effects Regression Model Coefficients for Cognitive Trajectories

Supplementary Table S5 Linear Mixed Effects Regression Model Coefficients Functional Trajectories

Supplementary Table S6 Linear Mixed Effects Regression Model Coefficients Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms Trajectories

Supplementary Table S7 Weibull Model Regression Coefficients for Time to Long-term Care Facility Placement

Supplementary Table S8 Two-part Model Regression Coefficients for Time Spent Receiving Formal Caregiving

Supplementary Table S9 Parameter Values in Best-case/Worst-case Sensitivity Analysis

Supplementary Table S10 Counterfactual Analysis

Supplementary Figure S1 Distribution of Survival Time

Supplementary Figure S2 Annual Total Cost of Dementia

Supplementary Figure S3 Best-worst Case Sensitivity Analysis Total and Net Cost of Dementia

Acknowledgments

The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed by the NIA funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Steven Ferris, PhD), P30 AG013854 (PI M. Marsel Mesulam, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG016570 (PI Marie-Francoise Chesselet, MD, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI Douglas Galasko, MD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Montine, MD, PhD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD), and P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD).

The Health and Retirement Study is produced and distributed by the University of Michigan with funding from the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740). Ann Arbor, MI.

RAND HRS Data, Version N. Produced by the RAND Center for the Study of Aging, with funding from the National Institute on Aging and the Social Security Administration. Santa Monica, CA.

Funding/Support: Dr. Jutkowitz received support from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1R36HS024165-01)

Sponsor’s Role: None.

Footnotes

MR. ERIC JUTKOWITZ (Orcid ID : 0000-0002-1735-8434)

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest. This work was funded by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1R36HS024165-01).

Author Contributions: Jutkowitz: obtained funding. All authors: study design. Jutkowitz: data collection and analysis. All authors: interpretation, drafting of manuscript, critical revision of manuscript, and approval of final manuscript.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association. 2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(4):459–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services. National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease: 2016 Update. ( https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/205581/NatlPlan2016.pdf)

- 3.Kelley AS, McGarry K, Gorges R, Skinner JS. The burden of health care costs for patients with dementia in the last 5 years of life. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2015;163(10):729–36. doi: 10.7326/M15-0381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, Langa KM. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(14):1326–1334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1204629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langa KM, Plassman BL, Wallace RB, et al. The Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study: study design and methods. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25(4):181–191. doi: 10.1159/000087448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beekly DL, Ramos EM, Lee WW, et al. The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) database: the uniform data set. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21(3):249–258. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318142774e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brookmeyer R, Corrada MM, Curriero FC, Kawas C. Survival following a diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(11):1764. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.11.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larson EB, Shadlen M-F, Wang L, et al. Survival after initial diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004;140(7):501–509. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-7-200404060-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho H, Klabunde CN, Yabroff KR, et al. Comorbidity-adjusted life expectancy: a new tool to inform recommendations for optimal screening strategies. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2013;159(10):667–676. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-10-201311190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arias E, Heron M, Tejada-Vera B. United States Life Tables, 2008. National vital statistics reports. 2012;61(3):1–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grand JH, Caspar S, MacDonald SW. Clinical features and multidisciplinary approaches to dementia care. JMDH. 2011;4:125. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S17773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jutkowitz E, MacLehose RF, Gaugler JE, Dowd B, Kuntz KM, Kane RL. Risk factors associated with cognitive, functional, and behavioral trajectories of newly diagnosed dementia patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(2):251–258. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jutkowitz E, Kuntz KM, Dowd B, Gaugler JE, MacLehose RF, Kane RL. Effects of cognition, function, and behavioral and psychological symptoms on out-of-pocket medical and nursing home expenditures and time spent caregiving for persons with dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(7):801–809. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jutkowitz E, Kane RL, Dowd B, Gaugler JE, MacLehose RF, Kuntz KM. Effects of cognition, function, and behavioral and psychological symptoms on Medicare expenditures and health care utilization for persons with dementia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(6):818–824. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Latimer N. NICE DSU technical support document 14: survival analysis for economic evaluations alongside clinical trials-extrapolation with patient-level data. Sheffield: Report by the Decision Support Unit. 2011 ( http://www.nicedsu.org.uk/NICE%20DSU%20TSD%20Survival%20analysis.updated%20March%202013.v2.pdf)

- 17.Arling G, Castelluccio P, Kane RL, Bershadsky J. Targeting residents for transition from nursing home to community prepared for the Area Agency on Aging of Northwest Arkansas. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim W, Irvin CV, Borck R. Factors predicting transitions from Medicare-Only to Medicare-Medicaid enrollee status. Mathematica Policy Research. 2014 ( https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/77001/MMTransV2.pdf)

- 19.Spillman B, Waidmann T. Rates and timing of Medicaid enrollment among older Americans Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Contract #HHSP23337033T. 2014 ( https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/134546/timing.pdf)

- 20.Vanni T, Karnon J, Madan J, White RG. Calibrating models in economic evaluation. Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29(1):3–49. doi: 10.2165/11584600-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juster FT, Suzman R. An overview of the Health and Retirement Study. Journal of Human Resources. 1995:S7–S56. [Google Scholar]

- 22.MetLife Mature Market Institute. Market Survey of Long-Term Care Costs. 2012 ( https://www.metlife.com/assets/cao/mmi/publications/studies/2012/studies/mmi-2012-market-survey-long-term-care-costs.pdf)

- 23.Chari AV, Engberg J, Ray KN, Mehrotra A. The opportunity costs of informal elder-care in the United States: new estimates from the American Time Use Survey. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(3):871–882. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.A Report on Shortfalls in Medicaid Funding for Nursing Center Care. 2012 ( https://www.ahcancal.org/research_data/funding/Documents/2012%20Report%20on%20Shortfalls%20in%20Medicaid%20Funding%20for%20Nursing%20Home%20Care.pdf)

- 25.Garfield R, Musumeci MB, Reaves E, Damico A. Medicaid’s role for people with dementia. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2015. ( http://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaids-role-for-people-with-dementia/) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bharmal MF, Dedhiya S, Craig BA, et al. Incremental dementia-related expenditures in a Medicaid population. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2012;20(1):73–83. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318209dce4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Briggs AH, Claxton K, Sculpher MJ. Decision Modelling for Health Economic Evaluation. Oxford University Press; USA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Briggs AH, Weinstein MC, Fenwick EAL, Karnon J, Sculpher MJ, Paltiel AD. Model parameter estimation and uncertainty: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force-6. Value in Health. 2012;15(6):835–842. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaugler JE, Kane RL. Family Caregiving in the New Normal. Academic Press; USA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Families caring for an aging America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS. Caregiver burden. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1052. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shirk C. Rebalancing Long-Term Care: The role of the Medicaid HCBS waiver program. 2006 ( http://www.w.nhpf.org/library/background-papers/BP_HCBS.Waivers_03-03-06.pdf)

- 33.Mor V, Zinn J, Gozalo P, Feng Z, Intrator O, Grabowski DC. Prospects for transferring nursing home residents to the community. Health Affairs. 2007;26(6):1762–1771. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.6.1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robison J, Porter M, Shugrue N, Kleppinger A, Lambert D. Connecticut’s “money follows the person” yields positive results for transitioning people out of institutions. Health Affairs 2AD. 34(10):1628–1636. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gitlin L, Hodgson N, Choi S, Marx KA. Interventions to address functional decline in persons with dementia: closing the gap between what a person “does do” and what they ‘can do’. In: Parks RW, Zec RF, Bondi MW, Jefferson AL, editors. Neuropsychology of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. 2nd. Oxford University Press; In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Neil ME, Freeman M, Portland VA. A systematic evidence review of non-pharmacological interventions for behavioral symptoms of dementia. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2011. ( http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/Dementia-Nonpharm.pdf) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brasure M, Jutkowitz E, Fuchs E, et al. Nonpharmacologic interventions for agitation and aggression in dementia. Comparative Effectiveness Review. 2016 Mar;(177):1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brodaty H, Arasaratnam C. Meta-analysis of nonpharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(9):946–953. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11101529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laver K, Dyer S, Whitehead C, Clemson L, Crotty M. Interventions to delay functional decline in people with dementia: a systematic review of systematic reviews. BMJ Open. 2016;6(4):e010767. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van’t Leven N, Prick A-EJC, Groenewoud JG, Roelofs PDDM, de Lange J, Pot AM. Dyadic interventions for community-dwelling people with dementia and their family caregivers: a systematic review. IPG. 2013;25(10):1581–1603. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213000860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang Z, Zhang K, Lin P-J, Clevenger C, Atherly A. A longitudinal analysis of the lifetime cost of dementia. Health Serv Res. 2011;47(4):1660–1678. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01365.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen JT, Neumann PJ. Decision analytic models for Alzheimer’s disease: state of the art and future directions. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4(3):212–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Green C, Shearer J, Ritchie CW, Zajicek JP. Model-based economic evaluation in Alzheimer’s disease: a review of the methods available to model Alzheimer’s disease progression. Value in Health. 2011;14(5):621–630. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Green C. Modelling Disease Progression in Alzheimer’s disease: a review of modelling methods used for cost-effectiveness analysis. PharmacoEconomics. 2007;25(9):735–750. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200725090-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hernandez L, Ozen A, DosSantos R, Getsios D. Systematic review of model-based economic evaluations of treatments for Alzheimer’s disease. PharmacoEconomics. 2016;34(7):681–707. doi: 10.1007/s40273-016-0392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1 Baseline Demographic Characteristics

Supplementary Table S2 Functional Domains

Supplementary Table S3 Behavioral and Psychological Symptom Domains

Supplementary Table S4 Linear Mixed Effects Regression Model Coefficients for Cognitive Trajectories

Supplementary Table S5 Linear Mixed Effects Regression Model Coefficients Functional Trajectories

Supplementary Table S6 Linear Mixed Effects Regression Model Coefficients Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms Trajectories

Supplementary Table S7 Weibull Model Regression Coefficients for Time to Long-term Care Facility Placement

Supplementary Table S8 Two-part Model Regression Coefficients for Time Spent Receiving Formal Caregiving

Supplementary Table S9 Parameter Values in Best-case/Worst-case Sensitivity Analysis

Supplementary Table S10 Counterfactual Analysis

Supplementary Figure S1 Distribution of Survival Time

Supplementary Figure S2 Annual Total Cost of Dementia

Supplementary Figure S3 Best-worst Case Sensitivity Analysis Total and Net Cost of Dementia