Abstract

Severe intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) remains a major cause of mortality and long-term neurologic morbidities in premature infants, despite recent advances in neonatal intensive care medicine. Several preclinical studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) transplantation in attenuating brain injuries resulting from severe IVH. Because there currently exists no effective intervention for severe IVH, the therapeutic potential of MSC transplantation in this intractable and devastating disease is creating excitement in this field. This review summarizes recent progress in stem cell research for treating neonatal brain injury due to severe IVH, with a particular focus on preclinical data concerning important issues, such as mechanism of protective action and determining optimal source, route, timing, and dose of MSC transplantation, and on the translation of these preclinical study results to a clinical trial.

Keywords: Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), Premature infant, Hydrocephalus, Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), Cell transplantation

Introduction

Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), a condition in which a germinal matrix hemorrhage ruptures through the ependyma into the lateral ventricle, is a common and serious disorder in premature infants1,2. As the risk and severity of IVH correlate with the extent of immaturity3,4, the actual number of preterm infants at high risk of developing severe IVH is increasing with the recent improved survival of very preterm infants through advances in perinatal medicine4. Premature infants with severe IVH (grade ≥3) have been associated with high mortality5, high risk of developing posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus (PHH), and long-term neurologic morbidities, such as seizures, cerebral palsy, mental retardation, and developmental and learning disabilities in survivors6–9. Although the pathogenesis of brain injury and PHH after severe IVH has not yet been clearly elucidated, it might result from inflammatory responses caused by blood contact and blood products in the subarachnoid space10,11. Hence, IVH and its resultant neurologic sequelae remain a major global health problem. However, no effective treatment is currently available to prevent PHH or attenuate brain damage after severe IVH in preterm infants. Therefore, the development of a new therapeutic modality to improve the prognosis of this intractable disease is urgently needed.

Previously, stem cells have been expected to have substantial potential for neuroprotection in various brain injuries in neonatal animals12 as well as intracranial hemorrhage in adult rats13. Recently, we have shown that exogenous administration of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) significantly attenuates brain damage and PHH after severe IVH in immunocompetent newborn rats14–16. These findings suggest that MSC transplantation might be a novel and promising therapeutic modality for the treatment of severe IVH in premature infants. In this review, we summarize the recent progress in MSC transplantation research for the treatment of severe IVH. In particular, we focused on preclinical data regarding important issues, such as optimal route of administration, timing, dose, safety profile, and short- and long-term outcomes of MSC transplantation, for clinical translation. Furthermore, the protocols used in our recently conducted phase I clinical trial of MSC transplantation in premature infants with severe IVH (NCT 02274428) are discussed.

Pathogenesis of Severe IVH and the Ensuing Brain Damage

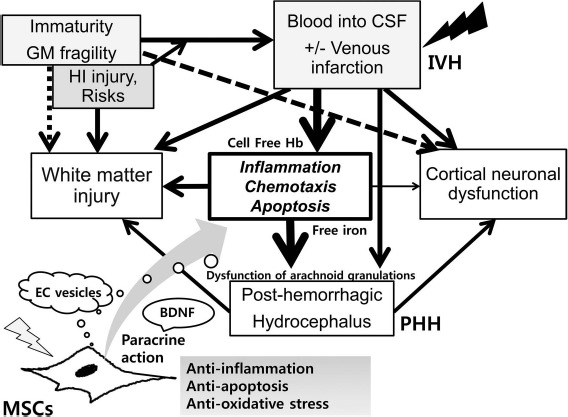

The pathogenesis of IVH is known to be complex and multifactorial (Fig. 1). It is primarily ascribed to an inherent fragility of the germinal matrix vasculature, disturbance in the cerebral blood flow, and platelet and coagulation disorders17–21. Immaturity of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), including paucity of pericytes, renders the germinal matrix vasculature fragile and thus contributes to the initiation of bleeding into the germinal matrix18,19. Multiple clinical risk factors, including vaginal delivery, low Apgar score, severe respiratory distress syndrome, pneumothorax, hypoxia, hypercapnia, seizures, and infection, may induce IVH primarily by disturbing the cerebral blood flow, and thrombocytopenia may contribute to IVH by causing hemostatic failure20,21.

Figure 1.

Pathogenesis of intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) and posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus (PHH); protection mechanism of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) transplantation on the development of PHH after severe IVH. IVH with or without venous infarction, defined as spontaneous bleeding from fragile germinal matrix (GM) into the ventricle, occurs in extremely premature infants that are usually exposed to various risks or hypoxic–ischemic (HI) injury. Cell-free hemoglobin (Hb) or free iron generated from extravasated blood in intraventricular space initiates inflammatory responses, chemotaxis, and apoptosis, which cause dysfunction of arachnoid granulations and reduction of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) resorption with retention of the CSF causing PHH after severe IVH. During the development of severe IVH and PHH, white matter injury and cortical neuronal dysfunction are inevitably accompanied. Transplanted MSCs after severe IVH exert anti-inflammatory, antiapoptotic, and antioxidative action through paracrine function, which counteract the progression of vicious cascade for injury and thus decrease the risk of development of PHH and subsequent white matter injury and neuronal dysfunction. MSC-derived extracellular (EC) vesicles are known to be the potential key mediators of MSC therapeutic action. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) secreted by transplanted MSCs is one of the critical paracrine factors mediating this neuroprotection against severe IVH.

After bleeding from the germinal matrix into the cerebral ventricles, subsequent hemolysis of the extravasated blood in the intraventricular space elevates the concentration of extracellular hemoglobin, and the cell-free hemoglobin initiates inflammatory responses, chemotaxis, and apoptosis22,23. The ensuing heme degradation also increases the concentrations of bilirubin, carbon monoxide, and free iron in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)24. Inflammatory responses in the microvascular barrier, activated by the extravasated blood in the CSF, could result in the dysfunction of arachnoid granulations, reducing the resorption of CSF. This imbalance in CSF production and resorption might result in the retention of the CSF and the progress of PHH after severe IVH. Taken together, the mechanism of brain damage in premature infants with severe IVH might be multifactorial and complex, including iron-induced free radical damage, inflammatory responses induced by proinflammatory cytokines, increased intra-cranial pressure, and the resultant decrease in cerebral perfusion pressure owing to PHH25,26.

Animal Models of Severe IVH and the Ensuing PHH

Developing an appropriate animal model that can simulate the clinical course of severe IVH in preterm infants is essential for understanding its pathophysiology and for testing the efficacy of potential new therapeutic modalities. Several animal species, including rodents, rabbits, sheep, pigs, dogs, cats, and primates, have been used as IVH models17,27–32. However, as each animal model has its own advantages and disadvantages, it is very difficult to develop a single animal model suitable for studying all the aspects of brain injury after severe IVH in premature infants. Intraperitoneal injection of glycerol into preterm rabbits delivered after 29 days of gestation (full-term 32 days) precipitated germinal matrix hemorrhage29. However, the usefulness of this IVH animal model is limited, as only 39% of these rabbit models developed clinically relevant grade ≥3 IVH that was severe enough to induce PHH in preterm infants29. Rodent models of IVH are relatively easy to use and maintain, are inexpensive to reproduce, and their neurobehavioral development and histopathology are already well described33–35. Germinal matrix hemorrhage was induced in newborn rats at postnatal day 7 (P7) with stereotactic injection of collagenase into the ganglionic eminence to reproduce the acute brain injury, gliosis, hydrocephalus, and periventricular leukomalacia observed in humans, but no PHH was observed in this animal model32,34. Another potential limitation of this model is that the germinal matrix has already regressed in the rat brain at P736. In another rat model, IVH was induced by bilaterally administering 80 μl of blood into the cerebral ventricle28 or into the periventricular region30. However, only 15%–65% of these models developed significant PHH27,28,30. We recently reported a newborn rat model of severe IVH by injecting 200 μl of dam's blood into its cerebral ventricles using a stereotaxic frame with a Hamilton syringe at P414,17, which is comparable to the developmental state of the brain of a ~27-week-old preterm infant37. With this method, 100% of the rats developed severe IVH at day 1, and about 85% of these pups subsequently progressed to PHH after 4 weeks of modeling. Besides the impaired sensorimotor function, augmented cell death, gliosis, inflammatory responses, and impaired myelination were also observed in this model. Overall, these findings suggest that this newborn rat pup animal model of IVH is suitable not only for the study of pathophysiological aspects of severe IVH, that is, how the extravasated blood activates inflammation in the subarachnoid space, leading to PHH and subsequent brain injury, but also for testing the therapeutic efficacy of potential new strategies, such as stem cell therapy.

MSC Characterization

Stem cell therapy has shown promising results in various brain injury or disease models38,39. MSCs have become a focus of research, as they are easily obtainable and do not have ethical and safety concerns, including the tumorigenic potential of embryonic stem cells (ESCs). MSCs have several unusual characteristics, including their fibroblast-like morphology; adherence to plastic; positive expression of CD73, CD90, and CD105; negative expression of CD45, CD34, CD14, CD11b, and HLA DR; and the capacity to differentiate into different cell types, such as adipocytes, chondrocytes, and osteoblasts40. MSCs are immune privileged because of their lack of major histocompatibility complex II antigen expression and their ability to inhibit proliferation and function of immune cells, such as dendritic cells, natural killer cells, and T and B lymphocytes41,42. These features allow for easier allogenic therapy with MSCs43.

MSCs have been detected and isolated from various adult tissues, including bone marrow (BM) and adipose tissue (AT), as well as from gestational tissues, such as placenta, amniotic fluid, Wharton's jelly, and umbilical cord blood (UCB). Although BM is the best characterized source of MSCs, its use is limited owing to its highly invasive acquisition process and low numbers of obtainable MSCs44. AT might be a potential alternative source of MSCs owing to its less-invasive harvesting procedure and larger quantities of obtainable MSCs, compared to that from BM. However, the therapeutic efficacy of AT-derived MSCs (ADSCs) in protecting against neonatal severe IVH has not yet been tested. Gestational tissues are medical waste and are usually discarded at birth. Therefore, MSCs obtained from gestational tissues are particularly attractive owing to their easy obtainability and lack of significant ethical concerns. Furthermore, older donor age has been shown to have a negative impact on the expansion and differentiation potential of MSCs, even when they originate from the same adult tissues of origin, such as AT45,46 or BM47. MSCs derived from gestational tissues, such as UCB, Wharton's jelly, or umbilical cord, exhibit lower immunogenicity48,49, higher proliferation capacity50,51 and paracrine potency52, and in vivo therapeutic efficacy53, compared to adult tissue-derived MSCs. Taken together, these findings suggest that as donor age is an important determinant of successful stem cell therapy, MSCs obtained from birth-associated tissues, such as UCB or Wharton's jelly, might be optimal sources for future clinical use in treating premature infants with severe IVH14–17.

Therapeutic Potential of MSC Transplantation in Severe IVH

As the pathophysiological mechanisms of brain injury and progression to PHH after severe IVH are complex and multifactorial, modulating only one factor might not be sufficient54. Thus, a multifaceted therapeutic agent would be necessary to improve the outcome of severe IVH. In our previous study, after induction of severe IVH at P4, intraventricular transplantation of MSCs (1 × 105 cells), but not fibroblasts, at P6 significantly attenuated the severe IVH-induced progress of PHH; augmented cell death, astrogliosis, and inflammatory responses; reduced corpus callosum thickness; impaired myelination; and impaired sensorimotor function14,17. We have also observed the beneficial effects of MSC transplantation, such as anti-apoptotic, anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic, and antioxidative paracrine and regenerative effects, in various animal disease models14,55–59. Collectively, considering their multiple therapeutic efficacies, MSCs, rather than other single therapeutic agents, might be the most suitable and promising candidates for therapies aimed at improving the prognosis of severe IVH in premature infants.

Protective Mechanisms of MSC Transplantation in Severe IVH

Owing to their multilineage differentiation potential, the protective mechanisms of MSC transplantation were initially ascribed to the transdifferentiation of the transplanted MSCs into neuronal cells60, thus reconstituting damaged brain parenchymal cells. However, very low rates of in vivo engraftment and differentiation of transplanted MSCs14,55,61 suggest that MSC survival might not be essential for their beneficial effects62,63. Thus, the therapeutic effects of MSCs might not be associated with their differentiation and direct replenishment of the damaged brain tissue.

Recent evidence suggests that the protective mechanisms of MSC transplantation may be mainly related to their ability to stimulate survival and recovery of damaged tissue as well as their anti-inflammatory and antiapoptotic paracrine effects through secretion of soluble factors, chemokines, and extracellular vesicles62–66 (Fig. 1). As MSC-derived extracellular vesicles are known to be the potential key mediators of MSC therapeutic action65,67, a cell-free preparation comprising MSC-derived extracellular vesicles could substitute MSCs for the treatment of preterm infants with severe IVH, thereby circumventing the putative side effects, such as tumor formation, associated with live stem cell treatments.

Several paracrine factors secreted by MSCs, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), nerve growth factor (NGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), insulin-like growth factor (IGF), and interleukins, have been known to enhance brain repair after hypoxia–ischemia68,69. However, the specific key paracrine factors secreted by transplanted MSCs that primarily mediate the protective paracrine anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, and antiapoptotic activities in severe IVH have not yet been elucidated. Combined DNA and antibody micro-array analyses enable us to simultaneously investigate the transcriptional and translational responses of MSCs following severe IVH, without any prior knowledge of their neuroprotective mechanisms. Recently, we observed significant upregulation of BDNF in both DNA and antibody microarray analyses16. Furthermore, knockdown of BDNF secreted by MSCs, by transfection with small interfering RNAs specific for human BDNF, abolished the neuroprotective effects of MSCs, such as significant attenuation of PHH, impaired behavioral test, increased apoptosis, inflammation, and astrogliosis, and reduced myelination, in newborn rats with severe IVH. These findings suggest that BDNF secreted by transplanted MSCs is a critical paracrine factor, playing a seminal role in attenuating severe IVH-induced brain injuries in newborn rats. Moreover, when MSCs from the same source, that is, from human UCB, were administered, VEGF secreted by transplanted MSCs played a critical role in attenuating hyperoxic lung injuries in neonatal rats57. Additionally, β-defensin 2 secreted by the MSCs, via the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling pathway, played a pivotal role in attenuating the acute lung injuries from Escherichia coli-induced pneumonia, through both its antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects70. Overall, variability in the paracrine factors secreted by MSCs from the same source, playing a critical role in mediating their therapeutic effects in different preclinical disease models16,57,71, suggests that there is a crosstalk between the host tissue and the transplanted MSCs64,72. Therefore, unlike drug treatment, which involves delivering a single agent at a specific dose, transplanted MSCs secrete various paracrine factors at variable concentrations in response to local microenvironmental cues73.

Optimal Route for MSC Transplantation

Determining the optimal route for MSC transplantation is a critical issue that needs to be addressed for its successful clinical translation in premature infants with severe IVH. MSCs have been transplanted via local intraventricular14,59, intrathecal74, intranasal75,76, systemic intraperitoneal56, and intravenous15 routes. The most convenient and minimally invasive systemic intravenous and intraperitoneal approaches show distinctive therapeutic advantages over the more invasive local intraventricular and intrathecal approaches, especially in very unstable preterm newborn infants who cannot tolerate invasive local injection. However, although systemically transplanted MSCs can cross the BBB in the injured brain15,77, they can also be retained in other organs, such as the lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys78. Although intranasal delivery of MSCs is minimally invasive, it would be practically impossible for clinical translation because of its lower therapeutic efficacy, requiring more than a fivefold increase in dose volume than that required for intraventricular transplantation75,76. In our recent study, although the doses of MSCs that were transplanted by the systemic intravenous route (5 × 105 cells) were fivefold higher than those transplanted by the local intraventricular route (1 × 105 cells), more MSCs localized to the brain with intraventricular administration than with intravenous administration15. However, both methods were equally effective in preventing PHH, attenuating impaired rotarod test, increasing terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling-positive cells, inflammatory cytokines, and astrogliosis, and reducing corpus callosum thickness and myelin basic protein (MBP) expression after severe IVH. Furthermore, as the anterior fontanel is open in newborn infants, local transplantation of MSCs is feasible in a clinical setting via a bedside ventricular tap, without any further invasive operation, in premature infants with severe IVH. Collectively, these findings suggest that local intraventricular or intrathecal, rather than systemic intravenous or intraperitoneal, transplantation of MSCs might be the more therapeutically effective delivery route for the treatment of preterm infants with severe IVH.

Optimal Timing of MSC Transplantation in Severe IVH

Determining the optimal timing of MSC transplantation is another major issue that remains to be clarified for its future clinical translation. The therapeutic time window of MSCs for brain injury has been quite variable, ranging from the first few hours to 10 days after the insult14,59,76,79,80. This wide variation in the therapeutic time window might be attributable to differences in animal models and severity of the hypoxic and/or ischemic insult. As the neuroprotective effects of MSCs may be mediated primarily by their paracrine anti-inflammatory and antiapoptotic properties49,81–83, MSCs must be transplanted at the very early phase after ischemic brain injury to induce neuroprotection82. In our recent study conducted to optimize the timing of MSC transplantation in severe IVH, we first performed time course experiments for inflammatory responses, showing a plateau peak up to 2 days after and a dramatic decline until 7 days after induction of severe IVH in newborn rats84. Early intraventricular transplantation of MSCs at 2 days, but not at 7 days, after induction of severe IVH significantly attenuated PHH development, impaired behavioral function tests, increased apoptosis, astrogliosis, and inflammatory responses, and reduced corpus callosum thickness and brain myelination. Our data on the protective effects of early MSC transplantation at the peak phase of inflammation, but not at the stabilization phase, after IVH induction suggest that low levels of inflammatory cytokines in the host tissue during the late stabilization phase of inflammation are insufficient to elicit the anti-inflammatory effects of MSCs. This phenomenon was also observed in other disease models, including mouse graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) models and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) models85,86. Taken together, these findings suggest that the therapeutic efficacy of MSCs could be enhanced or limited by a damaged host tissue microenvironment87. Therefore, the therapeutic time window for MSC transplantation might be narrow, and thus administration closer to the time of severe IVH might provide better therapeutic outcomes.

Optimal Dose of MSCs for Transplantation in Severe IVH

Determining the optimal dose of MSCs for transplantation is another key issue to be resolved for its future successful clinical translation in premature infants with severe IVH. Intraventricular transplantation of 1 × 105 cells significantly attenuated neonatal stroke88 and severe hypoxic–ischemic brain injury89 in newborn rats. Donega et al.76 demonstrated that intranasal transplantation of MSCs dose-dependently attenuated hypoxic–ischemic brain injury in newborn mice, showing best motor cog nitive and histologic outcomes at a dose of 1 × 106 cells, with 5 × 105 cells as the threshold effective dose. Recently, we observed that the therapeutically effective dose of MSCs for transplantation can be reduced from 5 × 105 to 1 × 105 cells by choosing local intraventricular administration over systemic intravenous administration to protect against severe IVH-induced brain injuries in newborn rats15. We also observed that local intratracheal transplantation of 5 × 105 MSCs was therapeutically more effective, compared to systemic intraperitoneal56 or intra venous71 administration of 2 × 106 cells, in attenuating hyperoxic lung injuries in newborn rats. Overall, these findings suggest that injury site and route of MSC administration are major determinants of optimal doses. In the light of these findings, further studies to determine the optimal dose of MSCs for transplantation, for maximal clinical benefit to preterm infants with severe IVH, are anticipated.

Short- and Long-Term Safety of MSC Transplantation

As safety comes first, for MSC transplantation, a longitudinal study of not only its therapeutic efficacy but also both short- and long-term safety in animal models is essential for its successful clinical translation. Both short- and long-term research is feasible using a rodent model in a short time frame, owing to its short life span. While the improvements in histologic, sensorimotor, and cognitive functions, impaired by hypoxic–ischemic brain injuries, after intranasal transplantation of MSCs in newborn mice persisted up to 14 months, no abnormalities, including neoplasia, were observed in the nasal turbinates, brain, or other organs90. Similarly, the protective and beneficial effects of intratracheal transplantation of MSCs were sustained without any long-term adverse effects in rats up to 70 days55 and 6 months of age91, comparable to human adolescence and mid-adulthood, respectively. Furthermore, in our previous phase I clinical trial, intratracheal transplantation of MSCs was safe and feasible, and no adverse outcomes, including tumorigenicity, were observed during follow-up of the infants up to 2 years of corrected age in more than 350 clinical studies of MSC transplantation conducted worldwide92. The transplanted MSCs did not engraft, and the number of donor cells decreased drastically 72 h after intranasal administration93, less than 1% was detected at 18 days after intracranial delivery94, and virtually no donor cells were detected at 70 days after intratracheal administration55. Thus, absence of long-term adverse effects, including tumorigenicity, following MSC transplantation may be attributable to the fact that they exert their therapeutic function by a “hit-and-run” mechanism95. The long-lasting protective effects of MSC transplantation, in spite of their short half-life, suggest that neuroprotection during the early critical time period of neonatal brain injury is essential for their persistent long-term neuroprotection. Collectively, the data indicating sustained protective effects of MSC transplantation, without any long-term adverse effects, warrant the translation of MSC transplantation to clinical trials for treatment of severe IVH in premature infants.

Phase I Clinical Trial for Severe IVH

On the basis of the promising evidence demonstrating neuroprotective effects of MSC transplantation in newborn rat models of severe IVH, a phase I dose-escalating clinical study on the safety and feasibility of human UCB-derived MSC transplantation in preterm infants with severe IVH has been designed and conducted (NCT02274428). This study was an open-label, single-center clinical trial to assess safety and feasibility of a single intraventricular transplantation of allogenic human UCB-derived MSCs within 7 days of detection of severe (grade ≥3) IVH in preterm infants. The first three infants were given a low dose (5 × 106 cells/kg in 1 ml/kg saline), and after confirming the absence of dose-limiting toxicity or serious adverse events associated with transplantation, the next six infants were given a higher dose (1 × 107 cells/kg in 2 ml/kg saline) under ultrasound guidance. The primary outcome measures were unsuspected death or anaphylactic shock within 6 h of MSC transplantation, and the secondary outcome measures were death or hydrocephalus, requiring shunt surgery, observed up to 1 year of age. We are planning to conduct long-term follow-up studies of these enrolled infants. The results from these currently conducted clinical trials can guide the way for future clinical introduction of MSC transplantation as a treatment for severe IVH in premature infants.

Conclusion

Exciting progress in different avenues of translational research has supported the hypothesis that MSC transplantation is greatly beneficial for protecting against brain injuries due to severe IVH. Clinical trials are harnessing the therapeutic potential of MSC transplantation for neuroprotection of premature infants with severe IVH. Although it is not a “magic cure” yet, this progress has brought MSC transplantation for severe IVH one step closer to its clinical translation. However, a better understanding of the neuroprotective mechanisms and resolution of critical issues, such as determining optimal source, timing, route, and dose, are required to permit future, safe clinical translation of MSC transplantation in premature infants with severe IVH.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (NRF-2014R1A1A3051220); the Korean Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family Affairs, Republic of Korea (HR14C0008); the 20 by 20 Project (GFO2160091) from Samsung Medical Center; and the Samsung Biomedical Research Institute grant (SMX1161301). Won Soon Park and Yun Sil Chang declare potential conflicts of interest arising from a filed or issued patent titled “Composition for treating intraventricular hemorrhage in preterm infants comprising mesenchymal stem cells” as co-inventors, not as patentees.

References

- 1.Payne AH, Hintz SR, Hibbs AM, Walsh MC, Vohr BR, Bann CM, Wilson-Costello DE. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of extremely low-gestational-age neonates with low-grade periventricular-intraventricular hemorrhage. JAMA Pediatr. 2013; 167(5): 451–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thorp JA, Jones PG, Clark RH, Knox E, Peabody JL. Perinatal factors associated with severe intracranial hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001; 185(4): 859–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vohr BR, Wright LL, Dusick AM, Mele L, Verter J, Steichen JJ, Simon NP, Wilson DC, Broyles S, Bauer CR, Delaney-Black V, Yolton KA, Fleisher BE, Paile LA, Kaplan MD,. Neurodevelopmental and functional outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network, 1993–1994. Pediatrics 2000; 105(6): 1216–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Walsh MC, Hale EC, Newman NS, Schibler K, Carlo WA, Kennedy KA, Poindexter BB, Finer NN, Ehrenkranz RA, Duara S, Sánchez PJ, O'Shea TM, Goldberg RN, Van Meurs KP, Faix RG, Phelps DL, Frantz ID 3rd. Neonatal outcomes of extremely preterm infants from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics 2010; 126(3): 443–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitelaw A. Intraventricular haemorrhage and posthaemorrhagic hydrocephalus: Pathogenesis, prevention and future interventions. Semin Neonatol. 2001; 6(2): 135–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy BP, Inder TE, Rooks V, Taylor GA, Anderson NJ, Mogridge N, Horwood LJ, Volpe JJ. Posthaemorrhagic ventricular dilatation in the premature infant: Natural history and predictors of outcome. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2002; 87(1): F37–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinto-Martin JA, Whitaker AH, Feldman JF, Van Rossem R, Paneth N,. Relation of cranial ultrasound abnormalities in low-birthweight infants to motor or cognitive performance at ages 2, 6, and 9 years. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1999; 41(12): 826–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.International PHVD Drug Trial Group. International randomised controlled trial of acetazolamide and furosemide in posthaemorrhagic ventricular dilatation in infancy. Lancet 1998; 352(9126): 433–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kennedy CR, Ayers S, Campbell MJ, Elbourne D, Hope P, Johnson A. Randomized, controlled trial of acetazolamide and furosemide in posthemorrhagic ventricular dilation in infancy: Follow-up at 1 year. Pediatrics 2001; 108(3): 597–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larroche JC. Post-haemorrhagic hydrocephalus in infancy. Anatomical study. Biol Neonate 1972; 20(3): 287–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hudgins RJ, Boydston WR, Hudgins PA, Morris R, Adler SM, Gilreath CL. Intrathecal urokinase as a treatment for intraventricular hemorrhage in the preterm infant. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1997; 26(6): 281–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Titomanlio L, Kavelaars A, Dalous J, Mani S, El Ghouzzi V, Heijnen C, Baud O, Gressens P,. Stem cell therapy for neonatal brain injury: Perspectives and challenges. Ann Neurol. 2011; 70(5): 698–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu AM, Lu G, Tsang KS, Li G, Wu Y, Huang ZS, Ng HK, Kung HF, Poon WS. Umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells with forced expression of hepatocyte growth factor enhance remyelination and functional recovery in a rat intracerebral hemorrhage model. Neurosurgery 2010; 67(2): 357–65; discussion 365–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahn SY, Chang YS, Sung DK, Sung SI, Yoo HS, Lee JH, Oh WI, Park WS. Mesenchymal stem cells prevent hydrocephalus after severe intraventricular hemorrhage. Stroke 2013; 44(2): 497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahn SY, Chang YS, Sung DK, Sung SI, Yoo HS, Im GH, Choi SJ, Park WS. Optimal route for mesenchymal stem cells transplantation after severe intraventricular hemorrhage in newborn rats. PLoS One 2015; 10(7): e0132919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahn SY, Chang YS, Sung DK, Sung SI, Ahn JY, Park WS. Pivotal role of brain derived neurotrophic factor secreted by mesenchymal stem cells in severe intraventricular hemorrhage in the newborn rats. Cell Transplant. 2017; 26(1): 145–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahn SY, Chang YS, Park WS. Mesenchymal stem cells transplantation for neuroprotection in preterm infants with severe intraventricular hemorrhage. Korean J Pediatr. 2014; 57(6): 251–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ballabh P. Intraventricular hemorrhage in premature infants: Mechanism of disease. Pediatr Res. 2010; 67(1): 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballabh P. Pathogenesis and prevention of intraventricular hemorrhage. Clin Perinatol. 2014; 41(1): 47–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ballabh P, Braun A, Nedergaard M. The blood-brain barrier: An overview: Structure, regulation, and clinical implications. Neurobiol Dis. 2004; 16(1): 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ballabh P, Braun A, Nedergaard M. Anatomic analysis of blood vessels in germinal matrix, cerebral cortex, and white matter in developing infants. Pediatr Res. 2004; 56(1): 117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang H, Wang PF, Zhou Y, Wang YC, Yang QW. Tolllike receptor 4 signaling in intracerebral hemorrhage-induced inflammation and injury. J Neuroinflammation 2013; 10: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xi G, Keep RF, Hoff JT. Mechanisms of brain injury after intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet Neurol. 2006; 5(1): 53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faivre B, Menu P, Labrude P, Vigneron C. Hemoglobin autooxidation/oxidation mechanisms and methemoglobin prevention or reduction processes in the bloodstream. Literature review and outline of autooxidation reaction. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 1998; 26(1): 17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhattathiri PS, Gregson B, Prasad KS, Mendelow AD, STICH Investigators. Intraventricular hemorrhage and hydrocephalus after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: Results from the STICH trial. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2006; 96: 65–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whitelaw A, Thoresen M, Pople I. Posthaemorrhagic ventricular dilatation. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2002; 86(2): F72–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balasubramaniam J, Del Bigio MR. Animal models of germinal matrix hemorrhage. J Child Neurol. 2006; 21(5): 365–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cherian SS, Love S, Silver IA, Porter HJ, Whitelaw AG, Thoresen M. Posthemorrhagic ventricular dilation in the neonate: Development and characterization of a rat model. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003; 62(3): 292–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Georgiadis P, Xu H, Chua C, Hu F, Collins L, Huynh C, Lagamma EF, Ballabh P. Characterization of acute brain injuries and neurobehavioral profiles in a rabbit model of germinal matrix hemorrhage. Stroke 2008; 39(12): 3378–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balasubramaniam J, Xue M, Buist RJ, Ivanco TL, Natuik S, Del Bigio MR. Persistent motor deficit following infusion of autologous blood into the periventricular region of neonatal rats. Exp Neurol. 2006; 197(1): 122–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goddard J, Lewis RM, Armstrong DL, Zeller RS. Moderate, rapidly induced hypertension as a cause of intraventricular hemorrhage in the newborn beagle model. J Pediatr. 1980; 96(6): 1057–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lekic T, Manaenko A, Rolland W, Krafft PR, Peters R, Hartman RE, Altay O, Tang J, Zhang JH. Rodent neonatal germinal matrix hemorrhage mimics the human brain injury, neurological consequences, and post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus. Exp Neurol. 2012; 236(1): 69–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudd TG, Allen DR, Smith FD. Technetium-99m-labeled methylene diphosphonate and hydroxyethylidine diphosphonate–-Biologic and clinical comparison: Concise communication. J Nucl Med. 1979; 20(8): 821–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lekic T, Manaenko A, Rolland W, Tang J, Zhang JH. A novel preclinical model of germinal matrix hemorrhage using neonatal rats. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2011; 111: 55–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lekic T, Rolland W, Hartman R, Kamper J, Suzuki H, Tang J, Zhang JH. Characterization of the brain injury, neurobehavioral profiles, and histopathology in a rat model of cerebellar hemorrhage. Exp Neurol. 2011; 227(1): 96–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romijn HJ, Hofman MA, Gramsbergen A. At what age is the developing cerebral cortex of the rat comparable to that of the full-term newborn human baby? Early Hum Dev. 1991; 26(1): 61–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dobbing J, Sands J. Comparative aspects of the brain growth spurt. Early Hum Dev. 1979; 3(1): 79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cao Q, Benton RL, Whittemore SR. Stem cell repair of central nervous system injury. J Neurosci Res 2002; 68(5): 501–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Windrem MS, Schanz SJ, Guo M, Tian GF, Washco V, Stanwood N, Rasband M, Roy NS, Nedergaard M, Havton LA, Wang S, Goldman SA. Neonatal chimerization with human glial progenitor cells can both remyelinate and rescue the otherwise lethally hypomyelinated shiverer mouse. Cell Stem Cell 2008; 2(6): 553–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spencer ND, Gimble JM, Lopez MJ. Mesenchymal stromal cells: Past, present, and future. Vet Surg. 2011; 40(2): 129–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beyth S, Borovsky Z, Mevorach D, Liebergall M, Gazit Z, Aslan H, Galun E, Rachmilewitz J. Human mesenchymal stem cells alter antigen-presenting cell maturation and induce T-cell unresponsiveness. Blood 2005; 105(5): 2214–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spaggiari GM, Capobianco A, Becchetti S, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Mesenchymal stem cell-natural killer cell interactions: Evidence that activated NK cells are capable of killing MSCs, whereas MSCs can inhibit IL-2-induced NK-cell proliferation. Blood 2006; 107(4): 1484–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noel D, Djouad F, Bouffi C, Mrugala D, Jorgensen C. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells and immune tolerance. Leuk Lymphoma 2007; 48(7): 1283–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mosna F, Sensebe L, Krampera M. Human bone marrow and adipose tissue mesenchymal stem cells: A user's guide. Stem Cells Dev. 2010; 19(10): 1449–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Choudhery MS, Badowski M, Muise A, Pierce J, Harris DT. Donor age negatively impacts adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cell expansion and differentiation. J Transl Med. 2014; 12: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dos-Anjos Vilaboa S, Navarro-Palou M, Llull R,. Age influence on stromal vascular fraction cell yield obtained from human lipoaspirates. Cytotherapy 2014; 16(8): 1092–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kretlow JD, Jin YQ, Liu W, Zhang WJ, Hong TH, Zhou G, Baggett LS, Mikos AG, Cao Y. Donor age and cell passage affects differentiation potential of murine bone marrow-derived stem cells. BMC Cell Biol. 2008; 9: 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rocha V, Wagner JE Jr, Sobocinski KA, Klein JP, Zhang MJ, Horowitz MM, Gluckman E,. Graft-versus-host disease in children who have received a cord-blood or bone marrow transplant from an HLA-identical sibling. Eurocord and International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry Working Committee on Alternative Donor and Stem Cell Sources. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342(25): 1846–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Le Blanc K. Immunomodulatory effects of fetal and adult mesenchymal stem cells. Cytotherapy 2003; 5(6): 485–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kern S, Eichler H, Stoeve J, Kluter H, Bieback K. Comparative analysis of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, or adipose tissue. Stem Cells 2006; 24(5): 1294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang SE, Ha CW, Jung M, Jin HJ, Lee M, Song H, Choi S, Oh W, Yang YS. Mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells developed in cultures from UC blood. Cytotherapy 2004; 6(5): 476–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Amable PR, Teixeira MV, Carias RB, Granjeiro JM, Borojevic R. Protein synthesis and secretion in human mesenchymal cells derived from bone marrow, adipose tissue and Wharton's jelly. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2014; 5(2): 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahn SY, Chang YS, Sung DK, Yoo HS, Sung SI, Choi SJ, Park WS. Cell type-dependent variation in paracrine potency determines therapeutic efficacy against neonatal hyperoxic lung injury. Cytotherapy 2015; 17(8): 1025–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dummula K, Vinukonda G, Chu P, Xing Y, Hu F, Mailk S, Csiszar A, Chua C, Mouton P, Kayton RJ, Brumberg JC, Bansal R, Ballabh P. Bone morphogenetic protein inhibition promotes neurological recovery after intraventricular hemorrhage. J Neurosci. 2011; 31(34): 12068–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ahn SY, Chang YS, Kim SY, Sung DK, Kim ES, Rime SY, Yu WJ, Choi SJ, Oh WI, Park WS. Long-term (postnatal day 70) outcome and safety of intratracheal transplantation of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells in neonatal hyperoxic lung injury. Yonsei Med J. 2013; 54(2): 416–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chang YS, Oh W, Choi SJ, Sung DK, Kim SY, Choi EY, Kang S, Jin HJ, Yang YS, Park WS. Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells attenuate hyperoxia-induced lung injury in neonatal rats. Cell Transplant. 2009; 18(8): 869–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chang YS, Ahn SY, Jeon HB, Sung DK, Kim ES, Sung SI, Yoo HS, Choi SJ, Oh WI, Park WS. Critical role of VEGF secreted by mesenchymal stem cells in hyperoxic lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2014; 51(3): 391–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chang YS, Choi SJ, Sung DK, Kim SY, Oh W, Yang YS, Park WS. Intratracheal transplantation of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells dose-dependently attenuates hyperoxia-induced lung injury in neonatal rats. Cell Transplant. 2011; 20(11–12): 1843–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim ES, Ahn SY, Im GH, Sung DK, Park YR, Choi SH, Choi SJ, Chang YS, Oh W, Lee JH, Park WS. Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation attenuates severe brain injury by permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in newborn rats. Pediatr Res. 2012; 72(3): 277–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krabbe C, Zimmer J, Meyer M. Neural transdifferentiation of mesenchymal stem cells–-A critical review. APMIS 2005; 113(11–12): 831–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Godfrey KM, James MP. Treatment of severe acne with isotretinoin in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Br J Dermatol. 1990; 123(5): 653–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Parekkadan B, van Poll D, Suganuma K, Carter EA, Berthiaume F, Tilles AW, Yarmush ML. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived molecules reverse fulminant hepatic failure. PLoS One 2007; 2(9): e941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Poll D, Parekkadan B, Cho CH, Berthiaume F, Nahmias Y, Tilles AW, Yarmush ML. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived molecules directly modulate hepatocellular death and regeneration in vitro and in vivo. Hepatology 2008; 47(5): 1634–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pluchino S, Cossetti C. How stem cells speak with host immune cells in inflammatory brain diseases. Glia 2013; 61(9): 1379–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sdrimas K, Kourembanas S. MSC microvesicles for the treatment of lung disease: A new paradigm for cell-free therapy. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014; 21(13): 1905–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kunter U, Rong S, Djuric Z, Boor P, Muller-Newen G, Yu D, Floege J,. Transplanted mesenchymal stem cells accelerate glomerular healing in experimental glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006; 17(8): 2202–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ophelders DR, Wolfs TG, Jellema RK, Zwanenburg A, Andriessen P, Delhaas T, Ludwig AK, Radtke S, Peters V, Janssen L, Giebel B, Kramer BW. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles protect the fetal brain after hypoxiaischemia. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2016; 5(6): 754–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rosell A, Morancho A, Navarro-Sobrino M, Martinez-Saez E, Hernandez-Guillamon M, Lope-Piedrafita S, Barcelo V, Borras F, Penalba A, Garcia-Bonilla L, Montaner J,. Factors secreted by endothelial progenitor cells enhance neurorepair responses after cerebral ischemia in mice. PLoS One 2013; 8(9): e73244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Grade S, Weng YC, Snapyan M, Kriz J, Malva JO, Saghatelyan A. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor promotes vasculature-associated migration of neuronal precursors toward the ischemic striatum. PLoS One 2013; 8(1): e55039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim ES, Chang YS, Choi SJ, Kim JK, Yoo HS, Ahn SY, Sung DK, Kim SY, Park YR, Park WS. Intratracheal transplantation of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells attenuates Escherichia coli-induced acute lung injury in mice. Respir Res. 2011; 12: 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sung DK, Chang YS, Ahn SY, Sung SI, Yoo HS, Choi SJ, Kim SY, Park WS. Optimal route for human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation to protect against neonatal hyperoxic lung injury: Gene expression profiles and histopathology. PLoS One 2015; 10(8): e0135574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.van Velthoven CT, Kavelaars A, Heijnen CJ. Mesenchymal stem cells as a treatment for neonatal ischemic brain damage. Pediatr Res. 2012; 71(4 Pt 2): 474–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Murphy MB, Moncivais K, Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells: Environmentally responsive therapeutics for regenerative medicine. Exp Mol Med. 2013; 45: e54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fang B, Wang H, Sun XJ, Li XQ, Ai CY, Tan WF, White PF, Ma H. Intrathecal transplantation of bone marrow stromal cells attenuates blood-spinal cord barrier disruption induced by spinal cord ischemia-reperfusion injury in rabbits. J Vasc Surg. 2013; 58(4): 1043–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Donega V, Nijboer CH, van Velthoven CT, Youssef SA, de Bruin A, van Bel F, Kavelaars A, Heijnen CJ,. Assessment of long-term safety and efficacy of intranasal mesenchymal stem cell treatment for neonatal brain injury in the mouse. Pediatr Res. 2015; 78(5): 520–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Donega V, van Velthoven CT, Nijboer CH, van Bel F, Kas MJ, Kavelaars A, Heijnen CJ,. Intranasal mesenchymal stem cell treatment for neonatal brain damage: Long-term cognitive and sensorimotor improvement. PLoS One 2013; 8(1): e51253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu L, Eckert MA, Riazifar H, Kang DK, Agalliu D, Zhao W. From blood to the brain: Can systemically transplanted mesenchymal stem cells cross the blood-brain barrier? Stem Cells Int. 2013; 2013: 435093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Aslam M, Baveja R, Liang OD, Fernandez-Gonzalez A, Lee C, Mitsialis SA, Kourembanas S,. Bone marrow stromal cells attenuate lung injury in a murine model of neonatal chronic lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009; 180(11): 1122–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yasuhara T, Hara K, Maki M, Xu L, Yu G, Ali MM, Masuda T, Yu SJ, Bae EK, Hayashi T, Matsukawa N, Kaneko Y, Kuzmin-Nichols N, Ellovitch S, Cruz EL, Klasko SK, Sanberg CD, Sanberg PR, Borlongan CV,. Mannitol facilitates neurotrophic factor up-regulation and behavioural recovery in neonatal hypoxic-ischaemic rats with human umbilical cord blood grafts. J Cell Mol Med. 2010; 14(4): 914–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Comi AM, Cho E, Mulholland JD, Hooper A, Li Q, Qu Y, Gary DS, McDonald JW, Johnston MV. Neural stem cells reduce brain injury after unilateral carotid ligation. Pediatr Neurol. 2008; 38(2): 86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Caplan AI, Dennis JE. Mesenchymal stem cells as trophic mediators. J Cell Biochem. 2006; 98(5): 1076–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Okazaki T, Magaki T, Takeda M, Kajiwara Y, Hanaya R, Sugiyama K, Arita K, Nishimura M, Kato Y, Kurisu K. Intravenous administration of bone marrow stromal cells increases survivin and Bcl-2 protein expression and improves sensorimotor function following ischemia in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2008; 430(2): 109–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Krampera M, Glennie S, Dyson J, Scott D, Laylor R, Simpson E, Dazzi F. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells inhibit the response of naive and memory antigen-specific T cells to their cognate peptide. Blood 2003; 101(9): 3722–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Park WS, Sung SI, Ahn SY, Sung DK, Im GH, Yoo HS, Choi SJ, Chang YS. Optimal timing of mesenchymal stem cell therapy for neonatal intraventricular hemorrhage. Cell Transplant. 2016; 25(6): 1131–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yanez R, Lamana ML, Garcia-Castro J, Colmenero I, Ramirez M, Bueren JA,. Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells have in vivo immunosuppressive properties applicable for the control of the graft-versus-host disease. Stem Cells 2006; 24(11): 2582–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zappia E, Casazza S, Pedemonte E, Benvenuto F, Bonanni I, Gerdoni E, Giunti D, Ceravolo A, Cazzanti F, Frassoni F, Mancardi G, Uccelli A. Mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis inducing T-cell anergy. Blood 2005; 106(5): 1755–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cotten CM, Murtha AP, Goldberg RN, Grotegut CA, Smith PB, Goldstein RF, Fisher KA, Gustafson KE, Waters-Pick B, Swamy GK, Rattray B, Tan S, Kurtzberg J,. Feasibility of autologous cord blood cells for infants with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J Pediatr. 2014; 164(5): 973–9.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kim ES, Ahn SY, Im GH, Sung DK, Park YR, Choi SH, Choi SJ, Chang YS, Oh W, Lee JH, Park WS. Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation attenuates severe brain injury by permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in newborn rats. Pediatr Res. 2012; 72(3): 277–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Park WS, Sung SI, Ahn SY, Yoo HS, Sung DK, Im GH, Choi SJ, Chang YS. Hypothermia augments neuroprotective activity of mesenchymal stem cells for neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. PLoS One 2015; 10(3): e0120893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Walter LM, Biggs SN, Nisbet LC, Weichard AJ, Muntinga M, Davey MJ, Anderson V, Nixon GM, Horne RS. Augmented cardiovascular responses to episodes of repetitive compared with isolated respiratory events in preschool children with sleep-disordered breathing. Pediatr Res. 2015; 78(5): 560–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pierro M, Ionescu L, Montemurro T, Vadivel A, Weissmann G, Oudit G, Emery D, Bodiga S, Eaton F, Peault B, Mosca F, Lazzari L, Thebaud B. Short-term, long-term and paracrine effect of human umbilical cord-derived stem cells in lung injury prevention and repair in experimental bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Thorax 2013; 68(5): 475–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chang YS, Ahn SY, Yoo HS, Sung SI, Choi SJ, Oh WI, Park WS. Mesenchymal stem cells for bronchopulmonary dysplasia: Phase 1 dose-escalation clinical trial. J Pediatr. 2014; 164(5): 966–72.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Donega V, Nijboer CH, van Tilborg G, Dijkhuizen RM, Kavelaars A, Heijnen CJ,. Intranasally administered mesenchymal stem cells promote a regenerative niche for repair of neonatal ischemic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2014; 261: 53–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.van Velthoven CT, Kavelaars A, van Bel F, Heijnen CJ,. Mesenchymal stem cell transplantation changes the gene expression profile of the neonatal ischemic brain. Brain Behav Immun. 2011; 25(7): 1342–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ankrum JA, Ong JF, Karp JM. Mesenchymal stem cells: Immune evasive, not immune privileged. Nat Biotechnol. 2014; 32(3): 252–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]