Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to determine the prognostic utility of the extent of lymph node involvement in patients with gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs) by analyzing population-based data.

Methods

Patients in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry were identified with histologically confirmed, surgically resected GEP-NETs. We divided patients into three lymph node ratio (LNR) groups based on the ratio of positive lymph nodes to total lymph nodes examined: ≤0.2, >0.2–0.5, and >0.5. Disease-specific survival was compared according to LNR group.

Results

We identified 3,133 patients with surgically resected GEP-NETs. Primary sites included stomach (11% of the total), pancreas (30%), colon (32%), appendix (20%), and rectum (7%). Survival was worse in patients with LNRs of ≤0.2 (hazard ratio [HR], 1.5; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.2–2.0), >0.2–0.5 (HR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.6–2.5), and >0.5 (HR, 3.1; 95% CI, 2.5–3.9) compared to N0 patients. Ten-year disease-specific survival decreased as LNR increased from N0 (81%) to ≤0.2 (69%), >0.2–0.5 (55%), and >0.5 (50%). Results were consistent for patients with both low and high grade tumors from most primary sites.

Conclusions

Degree of lymph node involvement is a prognostic factor at the most common GEP-NET sites. Higher LNR is associated with decreased survival.

Keywords: Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, Neuroendocrine tumor, Carcinoid, Prognosis, Lymph nodes, Survival Analysis

Introduction

Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs) are a diverse group of malignancies that arise from the diffuse neuroendocrine cell system. The incidence of these tumors has increased in recent years, and currently there are approximately 65,000 patients in the US with GEP-NETs.1–4 Patients experience clinical courses that range from relatively slow to aggressive due to heterogeneous tumor biology. In addition to tumor variability, treatment options similarly range from observation to surgical, hormonal, targeted, and systemic therapies.5–8

It is vital to accurately stage these malignancies in order to treat these patients optimally. Along with informing clinical discussions between patients and clinicians, staging allows for more accurate and homogeneous selection of patients for clinical trials.

The European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) and American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) guidelines classify all patients with lymph node positive NETs and no distant metastases as stage IIIb.9–11 In a number of cancers, the number of positive lymph nodes (LN) as well as the ratio of positive lymph nodes to total lymph nodes resected (LNR) has been shown to provide valuable prognostic information.12–19 Moreover, in a study published by our group, higher LNR was associated with worse survival in patients with small intestinal NETs (SI-NETs).20 We evaluated the prognostic significance of LNR in all remaining GEP-NET sites, specifically the stomach, pancreas, colon, appendix, and rectum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

We used data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program from the National Cancer Institute that collects information on cancer in 15 regions, covering approximately 30% of the US population. Patients were included if they were age 18 or older and diagnosed between 1988 and 2011 with pathologically confirmed, surgically resected GEP-NETs of the stomach, pancreas, appendix, colon, and rectum. Patients who were diagnosed after death or had incomplete tumor staging were excluded. Inclusion was also limited to stage IIIb tumors [any T, N1, M0: tumor of any size and depth (T1–T4), positive regional lymph node metastasis (N1), and no distant metastasis (M0)]. A reference population was used which included patients without regional lymph node metastasis, stages I–IIIa [any T, N0, M0: tumor of any size and depth (any T), no regional lymph node metastasis (N0), no distant metastasis (M0)]. SEER provided demographics on all patients including age, gender, race, and marital status. SEER also provided clinical characteristics including location of primary cancer; tumor size, depth, and local extension; involvement of lymph nodes; and distant metastases. This raw data was used to assign stage according to ENETS and AJCC criteria. ENETS and AJCC criteria were identical for the stomach, colon, rectum, and appendix. Because AJCC and ENETS staging criteria differ for both the pancreas and the appendix, patients with primaries from these locations were assigned TNM staging according to both guidelines. Tumor grade was assigned according to degree of differentiation, as defined in SEER. SEER data was used to classify surgical treatment for each primary site into the following four categories: local resection; partial or simple resection; total or radical resection; and resection, not otherwise specified (NOS).

We calculated LNR for each patient as the ratio between the number of positive lymph nodes and the total lymph nodes removed during surgical resection. Then, we divided the patients into three LNR groups (≤0.2, >0.2–0.5, and >0.5) and a group of lymph node negative (N0) patients. These divisions were based on a prior study showing significant differences between each group for SI-NETs.20

We used GEP-NET-specific survival as the primary study outcome in order to evaluate differences in prognosis based on LNR group. Survival time was defined as the duration from date of diagnosis until death or last follow-up (December 31, 2011). SEER data was used to determine cause of death. Patients who died from non-NET causes or were alive at last follow-up were censored.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis included comparison of patient characteristics in the three LNR groups. The chi square test, Wilcoxon rank sum, or ANOVA as appropriate were used to assess for significant differences in age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, primary tumor site, number of lymph nodes examined, T status, and category of surgical treatment. We used survival analysis to assess the primary outcome of GEP-NET-specific survival time by LNR group. Kaplan-Meier curves for each group were plotted up to ten years post-diagnosis. Survival between groups was compared using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards models were used to find the hazards of NET-specific death in each LNR group as compared to the reference population of N0 patients while adjusting for potential confounding variables. We adjusted for age, gender, marital status, race, primary site, T status, type of surgical resection, and number of lymph nodes examined. We performed the same analysis on the subset of patients with available tumor grade, comparing survival by LNR group separately in grade 1–2 and grade 3–4 NETs. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis wherein we restricted the cohort to patients with at least five lymph nodes resected. This was done to assess the influence of patients with small lymph node resections on our analysis. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) with two-sided p values.

RESULTS

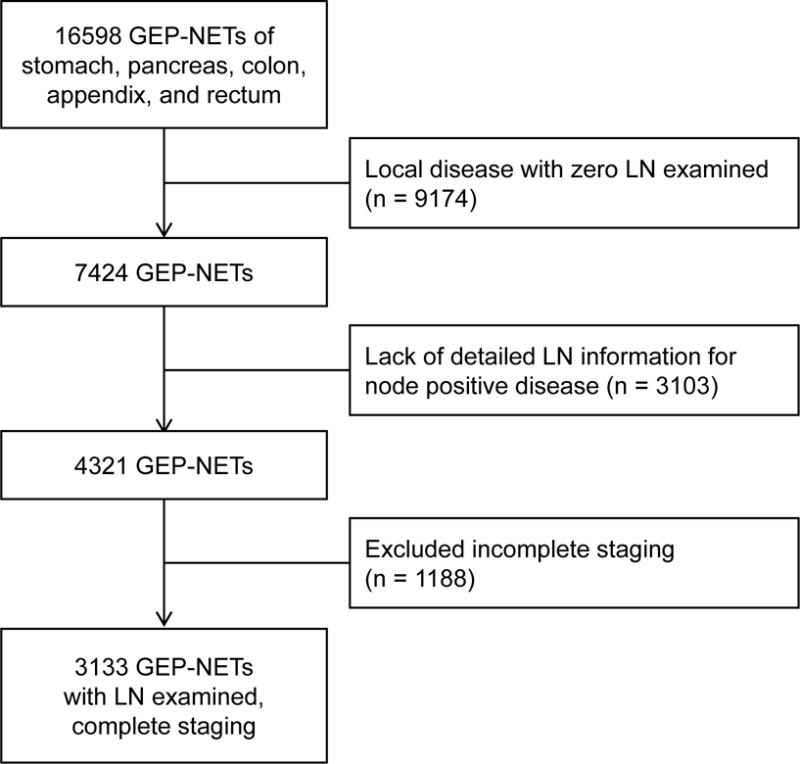

We identified 16,598 patients with GEP-NETs of the stomach, pancreas, colon, appendix, and rectum (Figure 1). From this initial group, there were 9,174 patients with local disease who had zero lymph nodes examined. We could not determine an LNR for 3,103 patients who had lymph node metastasis but no detailed lymph node information in the registry including the number of lymph nodes examined or the number of positive lymph nodes. There was incomplete staging information in the registry for 1188 patients. Our final cohort consisted of 3133 patients with GEP-NETs. Among these, 1346 had lymph node metastasis and 1787 had no lymph node involvement.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram for inclusion of patients in the study. Patients with multiple exclusion criteria are counted once.

Demographic characteristics for our cohort are listed in Table 1. The study population was 71% white, 13% black, 9% Hispanic, and 5% Asian. Approximately half of the patients were female. In the final cohort, primary sites in order of prevalence were colon (32% of the total), pancreas (30%), appendix (20%), stomach (11%), and rectum (7%). The median number of lymph nodes resected was 11 (interquartile range 5 – 17). Of the node-positive patients, 39%, 35%, and 26% had LNRs of ≤0.2, >0.2–0.5, and >0.5, respectively. Across LNR categories, our cohort had similar distributions of gender, marital status, and ethnicity. In contrast, there were differences in mean age at diagnosis, distribution of patients at each primary site, type of surgery, and number of lymph nodes examined.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics by LNR Group

| Characteristic | LNR Group

|

P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N0 | ≤0.2 | >0.2–0.5 | >0.5 | ||

| Age at diagnosis, mean (SD), y | 57 (15) | 57 (16) | 61 (15) | 63 (14) | <0.0001 |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 913 (51) | 276 (53) | 230 (48) | 168 (48) | 0.42 |

| Married, n (%) | 1113 (62) | 319 (61) | 282 (59) | 198 (57) | 0.25 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.55 | ||||

| White | 1276 (71) | 368 (70) | 334 (70) | 256 (74) | |

| Black | 209 (12) | 74 (14) | 67 (14) | 43 (12) | |

| Hispanic | 171 (10) | 43 (8) | 45 (9) | 27 (8) | |

| Asian | 83 (5) | 24 (5) | 21 (4) | 18 (5) | |

| Other | 48 (3) | 14 (3) | 9 (2) | 3 (1) | |

| Primary site, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||||

| Stomach | 176 (10) | 59 (11) | 53 (11) | 57 (16) | |

| Pancreas | 708 (40) | 88 (17) | 84 (18) | 48 (14) | |

| Appendix | 439 (25) | 132 (25) | 39 (8) | 23 (7) | |

| Colon | 350 (20) | 209 (40) | 266 (56) | 183 (53) | |

| Rectum | 114 (6) | 35 (7) | 34 (7) | 36 (10) | |

| LN examined, median (IQR) | 9 (4–15) | 16 (11–23) | 12 (7–17) | 8 (4–14) | <0.0001 |

| T status, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||||

| T1 | 506 (28) | 50 (10) | 23 (5) | 6 (2) | |

| T2 | 517 (29) | 129 (25) | 73 (15) | 49 (14) | |

| T3 | 544 (30) | 219 (42) | 272 (57) | 204 (59) | |

| T4 | 220 (12) | 125 (24) | 108 (23) | 88 (25) | |

| Surgery, n (%) | |||||

| Local | 47 (3) | 1 (1) | 3 (1) | 7 (2) | 0.0005 |

| Partial/simple | 1244 (70) | 380 (74) | 361 (77) | 265 (77) | |

| Total or radical | 454 (26) | 129 (25) | 98 (21) | 68 (20) | |

| Resection, NOS | 27 (2) | 6 (1) | 4 (1) | 3 (1) | |

LN indicates, lymph nodes; LNR, lymph node ratio; SD, standard deviation; IQR; interquartile range

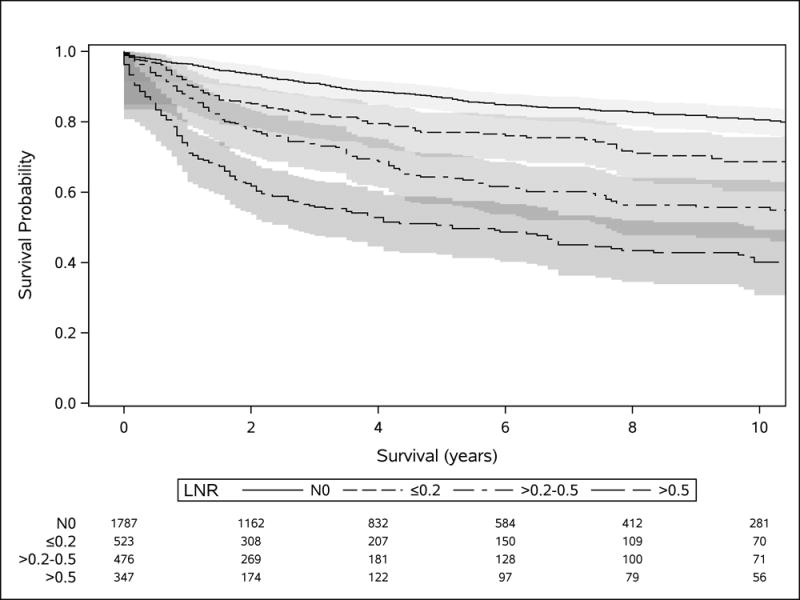

In our overall cohort, Kaplan-Meier analysis showed disease-specific survival was different between all LNR groups and progressively worse with higher LNRs (P < 0.0001). Hall-Wellner 95% confidence bands demonstrated minimal overlap of survival between groups (Figure 2). Ten-year disease-specific survival was 81%, 69%, 55%, and 50% for the N0, ≤0.2, >0.2–0.5, and >0.5, LNR groups, respectively. In adjusted analyses (Table 2), LNRs of ≤0.2 (hazard ratio [HR], 1.5; 95% CI, 1.2 – 2.0), >0.2–0.5 (HR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.6–2.5), and >0.5 (HR, 3.1; 95% CI, 2.5–3.9) were associated with worse disease-specific survival compared to the N0 group.

FIGURE 2.

Disease-specific survival of GEP-NETs from all sites by LNR group. Shading represents 95% Hall-Wellner confidence bands. The table shows the number of subjects at risk in each group at 2-year increments.

TABLE 2.

Influence of LNR on NET-Specific Mortality for All Sites and at Individual Primary Sites

| Primary Site | N | LNR | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Sites | 523 | ≤0.2 | 1.5 (1.2–2.0*) |

| 476 | >0.2–0.5 | 2.0 (1.6–2.5*) | |

| 347 | >0.5 | 3.1 (2.5–3.9*) | |

| Stomach | 59 | ≤0.2 | 1.1 (0.5–2.2) |

| 53 | >0.2–0.5 | 2.4 (1.3–4.5*) | |

| 57 | >0.5 | 2.7 (1.5–4.7*) | |

| Pancreas | 88 | ≤0.2 | 1.7 (1.0–2.9*) |

| 84 | >0.2–0.5 | 2.0 (1.2–3.1*) | |

| 48 | >0.5 | 1.1 (0.6–2.0) | |

| Appendix | 132 | ≤0.2 | 3.5 (1.8–7.0*) |

| 39 | >0.2–0.5 | 6.0 (3.0–12.4*) | |

| 23 | >0.5 | 7.1 (3.2–15.5*) | |

| Colon | 209 | ≤0.2 | 1.3 (0.9–2.0) |

| 266 | >0.2–0.5 | 1.4 (1.0–2.1*) | |

| 183 | >0.5 | 3.9 (2.8–5.4*) | |

| Rectum | 35 | ≤0.2 | 2.0 (0.8–5.0) |

| 34 | >0.2–0.5 | 2.7 (1.2–6.5*) | |

| 36 | >0.5 | 2.4 (1.1–5.3*) |

Adjusted for age, sex, marital status, race, primary site, T status, type of surgical resection, and number of lymph nodes examined. Reference group is N0.

P < 0.05

In site-specific analysis, results were consistent with those obtained in the overall cohort with worse survival among patients with LNRs of ≤0.2, >0.2–0.5, and >0.5 compared to N0 (Table 2). However, we observed that the LNR <0.2 group had similar survival to the N0 group among patients with NETs of the stomach, colon, and rectum. Additionally, a LNR >0.5 was not associated with worse disease-specific survival in pancreatic NETs. In pancreatic and appendiceal GEP-NETs, there were minor differences in AJCC and ENETS classification of T status, however the hazard ratios were similar for LNR groups in both staging systems.

We also assessed the association between LNR and survival in the subset of GEP-NETs patients with tumor grade data. Increasing LNR was associated with worse survival in well and intermediately differentiated GEP-NETs and in poorly differentiated and undifferentiated GEP-NETs. We additionally conducted a sensitivity analysis limited to patients with at least five lymph nodes resected. These results were similar to our original adjusted analysis which indicates the survival difference among LNR groups is not driven solely by patients with small lymph node resections.

DISCUSSION

Predicting outcomes in patients with GEP-NETs is complex. These tumors can be biologically heterogeneous, and outcomes can similarly vary depending on whether the disease course is indolent or aggressive. While lymph node status is an important factor in the GEP-NET staging system, current classification does not factor in the extent of lymph node involvement. In this study, we found an association between increasing LNR and worse survival in nearly all GEP-NETs. These findings, along with our previous data in small intestinal NETs,20 indicate that the extent of lymph node involvement accurately prognosticates patients with GEP-NETs. Further revision of the staging system including LNR status may be warranted to improve the management of these patients.

Consideration of the LNR may improve our ability to predict outcomes in patients with GEP-NETs. Projections of survival are particularly important for these tumors due to their high variability in prognosis. Survival estimates inform patient care decisions and also provide a basis for stratifying by disease severity in clinical trials. Moreover, the incidence of neuroendocrine tumors is increasing and new therapies are becoming available.21,22 Moving forward, more accurate prognostication may aid in the selection of an optimal treatment plan.

LNR is a useful metric compared to other prognostic markers as it is readily available, reproducible, and inexpensive in patients who have undergone surgical resection. In comparison, pathologists inconsistently obtain NET grade outside of tertiary or high volume centers. Chromogranin-A, the most common biomarker for tumor status, is informative but is falsely elevated by proton pump inhibitors, a common medication in patients with gastrointestinal pathology. Physical examination and clinical symptoms, if present, are markers of poor prognosis. However, only a minority of NETs cause classic syndromes such as carcinoid or symptoms of bulky disease.

Analyses stratified by tumor site showed relatively consistent relationship between higher LNR and worse disease prognosis suggesting that the LNR could be applied to all GEP-NETs. However, we did not see a survival difference for LNRs ≤0.2 in GEP-NETs of the stomach, colon, and rectum as compared to the N0 group. These differences may be explained by random variability. Additionally, we may have had insufficient power to identify true differences in survival given smaller sample size in some subgroups. Alternatively, these results may reflect true differences in the impact of LNR in certain tumor sites. If further validated, these findings may suggest that different classification systems are needed.

These results should be cautiously applied in the pancreas. In the pancreas, an LNR >0.5 was associated with no difference in survival from N0 patients. However, the ≤0.2 and >0.2–0.5 LNR groups had worse survival than the N0 group. It is unclear whether this is due to a true absence of an effect at higher LNRs or whether we were unable to detect an effect in our sample.

A strength of our analysis was that the SEER registry allowed us to study over three thousand patients with GEP-NETs including detailed information on lymph node metastasis. Data on demographics, tumor characteristics, and types of surgery were also available in order to adjust for potential confounders. We had access to sufficient long-term follow-up data to study survival in these commonly indolent tumors. The SEER data is also population-based which improves external validity by limiting referral bias and providing a sample that is more consistent with the US population.

One study weakness was limited information on tumor grade. Current WHO and ENETS classifications rely on the Ki-67 index or mitotic count for GEP-NET grade.23 Although SEER did not provide data on Ki-67 index or mitotic counts, we used information on differentiation grade to show that LNR retained prognostic significance after controlling for this factor. Additionally, there was considerable variability in the number of lymph nodes resected for each patient. When small numbers of lymph nodes are resected, LNR may be less reliable. In this study, however, sensitivity analysis limited to patients with at least five lymph nodes resected showed similar results.

A large number of patients were also excluded due to a lack of lymph node information in the registry. There are currently no guidelines for the number of lymph nodes to resect, and surgeons remove nodes based on clinical judgement. This is a shortcoming of our data, however it is also reflective of the clinical reality of treating neuroendocrine tumors where surgical resections vary.

In summary, our findings suggest that the extent of lymph node involvement is associated with survival across most GEP-NET primary sites. Patients with extensive lymph node metastasis may be considered for more aggressive treatment. Additionally, refined data on lymph node involvement may be used in conjunction with current staging guidelines to give more accurate prognosis for the clinical care and research of GEP-NET patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This work was supported by the American Cancer Society (MRSG-14-014-01-CCE to M.K.K.) and the National Institutes of Health (TL1TR001434 and UL1TR001433 to the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai).

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Jacob A. Martin, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY.

Richard R.P. Warner, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY.

Anne Aronson, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY.

Juan P. Wisnivesky, Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY.

Michelle Kang Kim, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY.

References

- 1.Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, et al. One Hundred Years After “Carcinoid”: Epidemiology of and Prognostic Factors for Neuroendocrine Tumors in 35,825 Cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3063–3072. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence B, Gustafsson BI, Chan A, et al. The epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsikitis VL, Wertheim BC, Guerrero MA. Trends of incidence and survival of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors in the United States: a seer analysis. J Cancer. 2012;3:292–302. doi: 10.7150/jca.4502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fraenkel M, Kim MK, Faggiano A, et al. Epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26:691–703. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warner RP. Neuroendocrine Tumors. In: Sands BE, editor. Mount Sinai Expert Guides. Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2014. pp. 279–291. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwekkeboom DJ, Krenning EP. Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy in the Treatment of Neuroendocrine Tumors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2016;30:179–191. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Narayanan S, Kunz PL. Role of Somatostatin Analogues in the Treatment of Neuroendocrine Tumors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2016;30:163–177. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulvey CK, Bergsland EK. Systemic Therapies for Advanced Gastrointestinal Carcinoid Tumors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2016;30:63–82. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rindi G, Klöppel G, Alhman H, et al. TNM staging of foregut (neuro)endocrine tumors: a consensus proposal including a grading system. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:395–401. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0250-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rindi G, Klöppel G, Couvelard A, et al. TNM staging of midgut and hindgut (neuro) endocrine tumors: a consensus proposal including a grading system. Virchows Arch. 2007;451:757–762. doi: 10.1007/s00428-007-0452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Compton CC, Byrd DR, Garcia-Aguilar J, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Atlas: A Companion to the Seventh Editions of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual and Handbook. Springer Science & Business Media; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vinh-Hung V, Cserni G, Burzykowski T, et al. Effect of the number of uninvolved nodes on survival in early breast cancer. Oncol Rep. 2003;10:363–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vinh-Hung V, Burzykowski T, Cserni G, et al. Functional form of the effect of the numbers of axillary nodes on survival in early breast cancer. Int J Oncol. 2003;22:697–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voordeckers M, Vinh-Hung V, Van de Steene J, et al. The lymph node ratio as prognostic factor in node-positive breast cancer. Radiother Oncol J Eur Soc Ther Radiol Oncol. 2004;70:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berger AC, Sigurdson ER, LeVoyer T, et al. Colon cancer survival is associated with decreasing ratio of metastatic to examined lymph nodes. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8706–8712. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.8852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herr HW. Superiority of ratio based lymph node staging for bladder cancer. J Urol. 2003;169:943–945. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000032474.22093.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee HY, Choi HJ, Park KJ, et al. Prognostic significance of metastatic lymph node ratio in node-positive colon carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1712–1717. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9322-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nitti D, Marchet A, Olivieri M, et al. Ratio between metastatic and examined lymph nodes is an independent prognostic factor after D2 resection for gastric cancer: analysis of a large European monoinstitutional experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:1077–1085. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.03.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jonnalagadda S, Arcinega J, Smith C, et al. Validation of the lymph node ratio as a prognostic factor in patients with N1 nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:4724–4731. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim MK, Warner RRP, Ward SC, et al. Prognostic Significance of Lymph Node Metastases in Small Intestinal Neuroendocrine Tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2015;101:55–65. doi: 10.1159/000371807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strosberg J, Wolin E, Chasen B, et al. 177-Lu-Dotatate significantly improves progression-free survival in patients with midgut neuroendocrine tumours: Results of the phase III NETTER-1 trial. Proceedings of the 2015 European Cancer Congress; Vienna, Austria. 2015. pp. 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Severi S, Sansovini M, Ianniello A, et al. Feasibility and utility of re-treatment with 177Lu-DOTATATE in GEP-NENs relapsed after treatment with 90Y-DOTATOC. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:1955–1963. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richards-Taylor S, Ewings SM, Jaynes E, et al. The assessment of Ki-67 as a prognostic marker in neuroendocrine tumours: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Pathol. 2016;69:612–618. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2015-203340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]