Abstract

The conserved, multifunctional Paf1 complex (Paf1C) regulates all stages of the RNA polymerase II transcription cycle. In this review, we examine a diverse set of recent studies from various organisms that build on foundational studies in budding yeast. These studies identify new roles for Paf1C in the control of gene expression and the regulation of chromatin structure. In exploring these advances, we find that Paf1C’s various functions, such as the regulation of promoter-proximal pausing and development in higher eukaryotes, are complex and context-dependent. As more becomes known about the role of Paf1C in human disease, interest in the molecular mechanisms underpinning Paf1C function will continue to increase.

Keywords: Paf1 complex, transcription elongation, RNA polymerase II, histone modifications

The multifunctional Paf1 complex

Each stage of the RNA polymerase II (Pol II) transcription cycle is extensively regulated by accessory proteins that directly impact Pol II activity, mediate its response to additional regulatory proteins or modify the chromatin template. The focus of this review, the Polymerase-Associated Factor 1 Complex (Paf1C), has been implicated in regulating all stages of the Pol II transcription cycle as well as events that follow transcript synthesis. Since the discovery of Paf1C as a novel Pol II-interacting complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae over twenty years ago [1–3], studies in budding yeast have led the way in elucidating the functions of this highly conserved protein complex. These foundational studies demonstrated that Paf1C regulates transcription elongation [4–6] as well transcription termination and RNA 3′-end formation [7–9] --- functions mediated at least in part through Paf1C promoting several critical cotranscriptional histone modifications [10–14].

In recent years, new roles for Paf1C have been identified in processes predominantly found in metazoans, particularly in the regulation of promoter-proximal pausing [15–17]. Studies in metazoans and in fission yeast have also advanced our understanding of previously characterized Paf1C functions, such as the maintenance of heterochromatin and the regulation of alternative cleavage and polyadenylation of mRNAs [18–21]. Furthermore, several new Paf1C-regulated histone modifications have been described that illuminate our understanding of the role that Paf1C plays in modulating chromatin structure [21, 22]. Given its fundamental role as a regulator of transcription, and its connections to human disease [23–26] and development [27, 28], interest in the functions of Paf1C in higher organisms will likely continue to expand. Here we examine a diverse set of studies in various organisms, and develop a view of Paf1C as a conserved, multifunctional regulator of eukaryotic gene expression.

Mechanisms of targeting Paf1C to chromatin

In budding yeast, Paf1C is composed of five subunits - Paf1, Ctr9, Cdc73, Leo1, and Rtf1. Some organisms, including humans, contain an additional subunit, the multifunctional Ski8/Wdr61 protein [29]. Moreover, in organisms other than budding yeast, ranging from fission yeast to humans, Rtf1 is not strongly associated with Paf1C and has been shown to function independently of other Paf1C subunits in certain contexts [18, 30, 31]. Although none of the subunits is essential in budding yeast, cells lacking Paf1 or Ctr9 have severe growth defects [32], and Paf1C orthologs are essential in higher organisms [33, 34]. Paf1 and Ctr9 are required for overall complex integrity [35, 36]; consistent with this, global protein levels of the other subunits are decreased in S. cerevisiae strains lacking Paf1 or Ctr9 [7].

In both yeast and human cells, Paf1C localizes to active genes at levels that correlate with transcriptional output [15, 16, 37, 38]. Several studies have explored the mechanisms that couple Paf1C and its various activities to Pol II (Figure 1, Key Figure). Early studies of Cdc73 (parafibromin in humans) showed that it interacts directly and stoichiometrically with purified Pol II [2] and is important for Paf1C recruitment [7]. The dynamically modified C-terminal domain (CTD) of Pol II serves as a hub that recruits an array of accessory factors to chromatin [39], and subsequent work showed that a conserved C-terminal domain within Cdc73 preferentially interacts with phosphorylated Pol II CTD peptides in vitro [40, 41]. A second attachment point between Paf1C and the Pol II elongation machinery is mediated by the elongation factor Spt5 [30, 41, 42], which interacts directly with a central region of the Rtf1 subunit [43, 44]. Both Spt5 and the Pol II CTD are substrates of the same kinase, Bur1 (CDK9 in humans), and the activity of this kinase is required for proper Paf1C recruitment in both yeast and human cells [16, 30, 41, 42, 45]. However, consistent with the weak association between Rtf1 and other Paf1C subunits in metazoans, a structure/function analysis of human Rtf1 suggests that Paf1C recruitment in humans may be primarily Rtf1-independent, at least at certain genes [31]. Interestingly, a recent cryo-EM analysis revealed that yeast Paf1C has a tripartite, mobile structure that contacts an extended region on the Pol II outer surface in the context of an elongation complex [46]. As predicted by its position in this elongation complex, Paf1C binds to Pol II in a manner stimulated by TFIIS and inhibited by the initiation factor TFIIF [46]. These new data indicate more extensive physical and functional interactions between Paf1C and the Pol II elongation machinery than previously predicted through analyses of individual subunits.

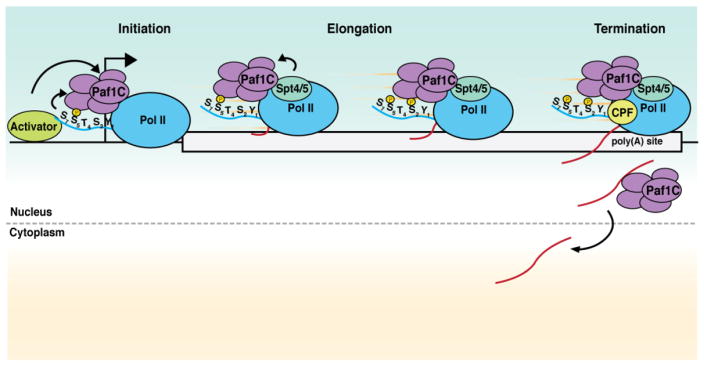

Figure 1. Paf1C is involved in RNA synthesis from beginning to end.

Paf1C can be recruited to promoters and enhancers by transcriptional activators in metazoans. Upon the transition to elongation, Paf1C directly binds to Pol II via interactions with the CTD and the Pol II outer surface and to the elongation factor Spt4/5 (DSIF in humans). In yeast, these methods of recruitment appear to predominate. Pol II is phosphorylated at serine 2 (Ser2) during elongation. As transcription ends, the growing transcript is polyadenylated and cleaved at sites defined in part by Paf1C, which interacts with the cleavage and polyadenylation machinery (CPF). Paf1C then helps determine which transcripts are exported to the cytoplasm.

At most genes in S. cerevisiae, Paf1C occupancy peaks downstream of the transcription start site near the +2 and +3 nucleosomes [37, 38]. This enrichment pattern is consistent with an ordered recruitment model in which Paf1C joins the elongation machinery after Spt5 has associated with Pol II. However, in higher eukaryotic systems, the pattern of Paf1C enrichment differs from that observed in budding yeast, possibly reflecting different recruitment strategies predominant in different systems. For example, in some mouse and human cells, Paf1C occupancy was reported to be highest near the transcription start and end sites (TSS and TES) [15, 16, 18]. This is interesting in light of several studies in higher eukaryotes indicating that Paf1C is recruited to promoters and enhancers by transcriptional activators (Figure 1). In one study, a transient complex between Paf1C and the proto-oncogenic transcription factor c-Myc was identified and found to inhibit activation of c-Myc target genes [47]. Transactivators of viral genomes have also exploited interactions with Paf1C. For example, the adenovirus E1A protein recruits Paf1C to promoters, leading to the activation of both viral and host genes in a Paf1C-dependent manner [48, 49].

Several studies have also identified an important role for parafibromin, the human ortholog of Cdc73, in regulating the transcriptional output of the developmentally critical Wnt, Hedgehog, and Notch signaling pathways through direct interactions with the downstream effectors of these pathways [33, 50]. The interactions between parafibromin and the effectors of the Wnt and Hedgehog pathways (β-catenin and Gli1, respectively) utilize the same N-terminal segment of parafibromin and are mutually exclusive [50]. In contrast, parafibromin can simultaneously interact with the Wnt and Notch signaling effectors, allowing for coordinate stimulation of these two pathways. Interestingly, parafibromin is capable of stimulating transcription of Wnt target genes even upon depletion of Paf1, which should preclude formation of a stable Paf1C [51]. This is consistent with data showing that murine Cdc73 is specifically enriched at promoters under certain conditions [18].

Taken together, these data indicate that while Paf1C recruitment to promoters and enhancers may represent a general recruitment mechanism in higher organisms and may delineate a class of genes as Paf1C-regulated in response to various signals, the means by which Paf1C modulates the expression of any given gene is likely to depend on gene- and cell type-specific factors.

Paf1C regulates gene expression through diverse mechanisms

Strong support for a role of Paf1C in transcription elongation first came from experiments in budding yeast, which showed that Paf1C is recruited to actively transcribed open reading frames (ORFs) [52] and interacts physically and genetically with transcription elongation factors, including the Spt4–Spt5 complex and the FACT histone chaperone complex [4, 5, 53]. An early study using yeast extracts and a naked DNA template revealed a direct role for Paf1C as a positive effector of transcription in vitro [6], and a more recent study showed that reconstituted human Paf1C promotes elongation through a chromatinized template both independently and in concert with the elongation factor TFIIS/SII [35]. In the cell, deletion or knockdown of Paf1C components alters the expression of many genes, and the results indicate both positive and negative effects of the complex on transcript levels [2, 8, 31].

In recent years, much attention has been given to the importance of promoter-proximal pausing of Pol II in regulating transcription elongation at many genes in metazoans [54]. The pausing of Pol II 20–60 bp into the transcription unit poises genes for rapid induction in response to external stimuli and maintains promoter-proximal regions in a nucleosome-depleted state [54]. The transcription elongation factor DSIF (human ortholog of the yeast Spt4–Spt5 complex) acts in concert with another protein complex, NELF, to establish promoter-proximal pausing of Pol II [55] (Figure 2). Release from pausing is triggered by phosphorylation of NELF and Spt5 by P-TEFb (CDK9-cyclin T complex), upon which NELF dissociates from the polymerase and DSIF becomes a positive elongation factor [55].

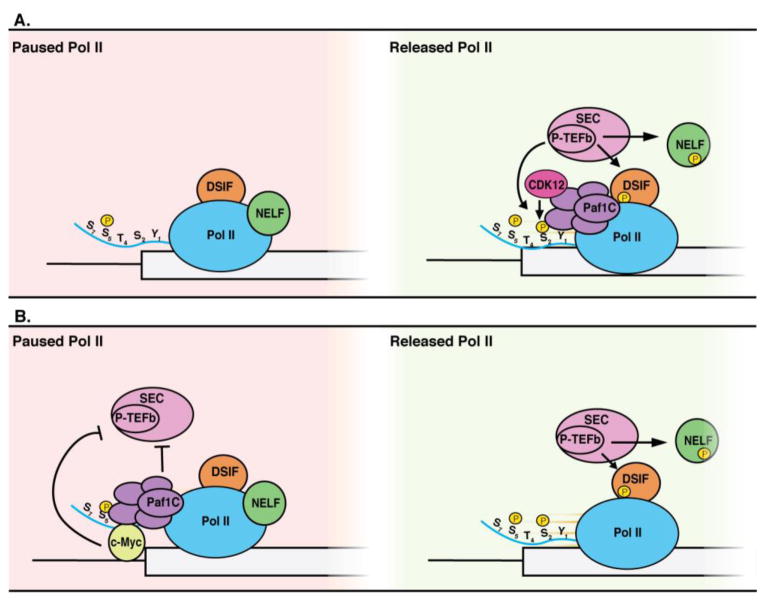

Figure 2. Paf1C regulates Pol II pause and release.

(A) Paf1C activates Pol II release by recruiting the super elongation complex (SEC), which contains P-TEFb. The CDK9 subunit of P-TEFb then phosphorylates NELF, DSIF and Pol II Ser2. Phosphorylated NELF dissociates from Pol II, releasing Pol II for productive elongation. Paf1C also recruits CDK12, the major kinase for Pol II Ser2. (B) Paf1C can also stabilize Pol II pausing by preventing SEC and P-TEFb from associating with genes. In the case of Myc target genes, Paf1C binds transiently to c-Myc, and this interaction inhibits P-TEFb recruitment and results in stabilization of Pol II pausing.

Several recent studies have identified Paf1C as a factor that regulates promoter proximal pausing [16, 17, 56]. One genome-wide survey of Pol II and Paf1C occupancy in human monocytic leukemia (THP1) cells indicated that Paf1C promotes release from pausing at > 5,800 genes [16] (Figure 2A). This study identified a mutual dependence of Paf1C and P-TEFb with respect to their recruitment to/retention on active chromatin [16], an observation consistent with a positive feedback model in which Paf1C promotes pause release by regulating the chromatin association of P-TEFb both directly and via Paf1C-dependent histone modifications (see below) [56]. Another report postulates the existence of at least four unique P-TEFb-containing super elongation complexes (SECs), each with distinct targets for CDK9 activity [17]. Paf1C is critical for the recruitment of two of these SEC subtypes. In this model, Paf1C interacts with AFF1-SEC to recruit P-TEFb to NELF-A, and subsequently with AFF4-SEC to recruit P-TEFb to the Pol II CTD (Figure 2A). It is believed that a direct interaction between the Paf1 subunit and AF9, a component of both of the above SEC subtypes, is responsible for facilitating this recruitment [57], although others have detected Paf1C binding to CDK9 independently of AF9 [16].

In contrast to studies that implicated Paf1C in pause release, other studies have demonstrated a role for Paf1C in establishing or maintaining the pause (Figure 2B). Depletion of Paf1 in human colon cancer cells resulted in a genome-wide increase in the ratio of Pol II in gene bodies relative to promoters, suggesting that Paf1 inhibits release from pausing at a large number of genes in this context [15]. Global run-on sequencing (GRO-seq) and nascent RNA-seq in Paf1-depleted cells detected increased transcription of these genes. Furthermore, enhanced enrichment of a CDK9-containing AFF4-SEC complex was observed in Paf1 deficient cells, establishing a model whereby Paf1C promotes pausing by inhibiting the recruitment of P-TEFb in the context of SEC [15]. Similar results were seen in another cancer cell line (MCF7) as well as in Drosophila, and interestingly, the same study that found that a majority of genes displayed more pausing upon Paf1C depletion in THP1 cells observed the opposite effect in human acute lymphoblastic leukemia CCRF-CEM cells [16]. Also of note is the observation that turnover of c-Myc promotes P-TEFb recruitment [47]. When c-Myc turnover is inhibited, a transient c-Myc-Paf1C complex (see above) is stabilized and transcription of Myc targets is downregulated [47]. It is possible that cellular environments that stabilize this complex may also inhibit P-TEFb recruitment. Taken together, these observations argue that the role of Paf1C in regulating pausing is complex and may depend on secondary genetic or physiological factors.

Phosphorylation of the serine 2 residues in the CTD heptad repeats (Ser2P) of Pol II is strongly associated with transcription elongation. While Ser2P is dependent on CDK9, recent studies indicate that the major Ser2P kinase is CDK12 [58]. Interestingly, Paf1C has been shown to recruit CDK12 to chromatin [16]. Because the interaction between Paf1C and CDK12 is stronger than that between CDK12 and Pol II [16], it is possible that Paf1C is important for transferring CDK12 to elongating Pol II. A recent report suggests that Ser2P occurs downstream of pause release [17], suggesting that Paf1C’s role in pause release may relate more to its interactions with P-TEFb [16, 17], which targets numerous pausing factors, than to its involvement in CDK12 recruitment.

While at many genes Paf1C likely impacts transcript levels by direct and chromatin-mediated effects (see below) on Pol II elongation, several studies have implicated Paf1C in co- and post-transcriptional RNA processing events. Polyadenylation (pA) of mRNAs takes place cotranscriptionally [59, 60], and Pol II pausing also occurs upon transcription through the pA site and prior to termination [61]. One known function of Pol II CTD-Ser2P is the recruitment of RNA 3′ processing factors to the pA site [62, 63]. A role for Paf1C in the regulation of mRNA processing was first suggested by studies in budding yeast, which showed that loss of Paf1C subunits leads to shortened poly(A) tails and alternative pA site selection [7, 8]. In support of a direct role for Paf1C in this process, physical interactions between Paf1C subunits and multiple cleavage and polyadenylation factors have been detected [9, 64], and Paf1C has also been shown to stimulate transcript cleavage and polyadenylation in vitro [65] (Figure 1).

In contrast to budding yeast, where Paf1C dissociates from chromatin just upstream of the pA site [38], mammalian Paf1C occupancy persists downstream of the pA site [18]. A recent study showed that depletion of specific Paf1C subunits from mouse myoblasts caused global alterations in pA site selection, with increased use of alternative pA sites in introns and internal exons [18]. At genes with upregulation of intronic or exonic pA site usage following Paf1C depletion, transcription is diminished [18]. Interestingly, Paf1C is enriched in the bodies of these genes, suggesting a direct role in guarding against alternative pA site selection. [18]. Whether Paf1C impacts pA site selection by controlling Pol II elongation rates or by affecting the recruitment/activity of cleavage and polyadenylation factors remains to be clarified.

Emerging evidence also suggests that, distinct from its role in promoting elongation, Paf1C controls the fate of nascent transcripts. Global analysis in budding yeast found that Paf1C enrichment at ORFs promotes the nuclear export of nascent transcripts, while Paf1C depletion leads to their retention and degradation [66] (Figure 1). Paf1C enrichment in gene bodies was shown to be governed at least in part by promoter elements [66], although it is as yet unclear whether Paf1C is recruited to budding yeast promoters by transcription factors, as in higher organisms. In support of the idea that Paf1C regulates gene expression at the post-transcriptional level, a very recent study employing PAR-CLIP technology revealed RNA crosslinking to all five Paf1C subunits in yeast [67].

Collectively, these observations point to diverse roles of Paf1C in regulating gene expression through direct effects on the Pol II elongation machinery and through assisting in the maturation and export of RNA products. The extent to which these functions of Paf1C overlap with its roles in chromatin modification is an important area for future study.

Paf1C governs chromatin structure

Eukaryotic transcription takes place on chromatin, and post-translational modification of the core histone proteins regulates Pol II transcription by effecting dynamic changes in chromatin. Paf1C was first implicated in the regulation of cotranscriptional histone modifications by studies showing that it is required for the conserved monoubiquitylation (ub) of a lysine near the C terminus of histone H2B (K123 in budding yeast, and K120 in humans) as well as H2Bub-dependent methylation of H3 K4 and H3 K79 [10–13] (Figure 3). H2Bub inhibits chromatin compaction [68] and is associated with regions of active transcription, but regulates transcript levels both positively and negatively for a subset of genes [69–72], particularly genes where transcription is rapidly induced in response to various stimuli [71]. The precise mechanisms of feedback and regulation between transcription and H2B K123ub, and the role of Paf1C in regulating these processes, are not fully defined. H2Bub is catalyzed by the ubiquitin conjugase (E2) Rad6 and the dimeric ubiquitin ligase (E3) Bre1 (UBE2A/2B and RNF20/40 in humans, respectively). Interestingly, a domain within the Rtf1 subunit required for H2Bub [73, 74] interacts directly with Rad6 in budding yeast cells and stimulates Rad6 and Bre1-dependent H2Bub in a minimal, transcription-free in vitro system [37]. Transcription is thought to be a prerequisite for H2Bub in vivo [75], perhaps reflecting transcription-dependent localization of the ubiquitylation machinery.

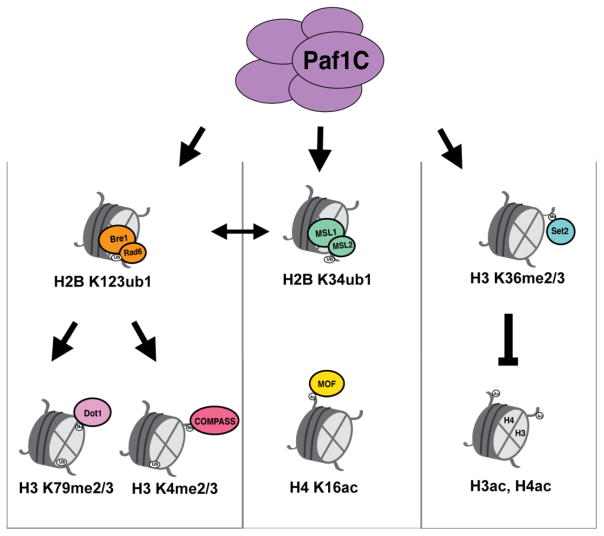

Figure 3. Paf1C controls multiple histone modification cascades.

Paf1C stimulates monoubiquitylation (ub1) of H2B K123 (and K120 in humans) through interaction with Rad6, which works with Bre1 to catalyze H2B K123ub1. This mark is a prerequisite for di- and tri-methylation (me2/3) of H3 K79 and H3 K4, placed by the methyltransferases Dot1 and COMPASS, respectively. Paf1C interacts with the MSL1/2 complex to activate H2B K34ub1. H2B K120ub1 and H2B K34ub1 are interdependent marks, as MSL1/2 can interact with the H2B K120ub1 machinery to promote H2B K34ub1 and vice versa. H4 K16 acetylation by MOF is reduced in the absence of Paf1C. Independent of H2Bub is H3 K36me2/3. The Paf1, Cdc73 and Ctr9 subunits of Paf1C are required for H3K36me3. H3 K36me2/3 subsequently causes H3 and H4 deacetylation through the recruitment of a histone deacetylase complex.

In humans, H2B can also be monoubiquitylated on K34, a mark catalyzed by the heterodimeric ubiquitin ligase MSL1/2 [22]. H2B K34ub appears to stimulate H3 K4 and H3 K79 methylation directly, similarly to H2B K120ub [22]. This raised the question of whether Paf1C and/or H2B K120ub might also regulate, or be regulated by, H2B K34ub. Indeed, a subsequent report found that knockdown of Paf1 led to substantially decreased levels of both H2Bub marks in HeLa cells, as well as a reduction in the chromatin association of both E3 enzymes [56] (Figure 3). The two marks appear interdependent, as RNF20/40 promotes both H2B K34ub and MSL1/2 chromatin association and vice versa. In vitro binding assays showed that different regions of MSL1/2 mediate direct interactions with RNF20/40 and with Paf1C. This binding is cooperative, meaning that the interactions may occur simultaneously and leading to a model whereby Paf1C promotes the attachment of both E3s to chromatin [56].

The extent to which H2Bub contributes to Paf1C regulation of promoter-proximal pausing is unclear. In HeLa cells, CDK9 promotes both H2B K34ub and H2B K120ub, and is dependent on the marks for its chromatin association [56]. In contrast, in cells where Paf1C promotes pausing, H2Bub does not appear linked to this regulation [15]. However, Paf1C-mediated H2Bub may also be implicated in P-TEFb functions that occur either downstream of pause release, or in organisms like budding yeast that lack canonical Pol II pausing. Deletion of the RTF1 gene suppresses the growth defect caused by a hypofunctional version of the CDK9 homologue in S. cerevisiae, Bur1, while absence of other Paf1C members exacerbates the growth defect [14], and H2Bub-related phenotypes are suppressed by a reduction in Cdk9 activity in S. pombe [76]. As in metazoans, Prf1, the fission yeast ortholog of Paf1C subunit Rtf1, fails to copurify with other Paf1C members [30]. It has been suggested that Paf1C and Rtf1/Prf1 are recruited through distinct mechanisms in S. pombe involving distinct P-TEFb substrates [30].

In addition to abrogating H2B K34ub and H2B K120ub, Paf1 depletion globally reduces H4 K16 acetylation (ac) [56] (Figure 3). H4 K16 is acetylated by MOF, which is stably associated with two complexes: NSL-MOF and the MSL1/2-containing MSL-MOF [77]. Of particular interest is the role that MOF-mediated H4 K16ac may play in the formation of heterochromatin. The boundaries between euchromatin and heterochromatin are demarcated by a diverse group of boundary elements that act to prevent heterochromatin spreading into actively transcribed regions [78]. H4 K16ac is enriched at boundary elements and was shown to prevent heterochromatin spreading in S. pombe [79]. A genetic screen for factors regulating heterochromatin formation identified Paf1C as a negative regulator of heterochromatin spreading [21]. H4 K16ac at boundary elements is diminished in leo1Δ cells, and Leo1 mutants are defective in recruitment of the orthologous H4 K16 acetyltransferase Mst1.

Heterochromatin formation in S. pombe and many other organisms is dependent on the RNAi pathway. Recently, a screen for factors that negatively regulate RNAi-mediated heterochromatin formation identified all five Paf1C subunits [19]. Paf1C mutants are permissive for RNAi-directed heterochromatin formation, and this repressed state is stable across many generations. A similar phenotype was observed in mutants defective for both transcription termination and release of the nascent transcript [19], both well-characterized Paf1C functions, suggesting that Paf1C restricts the formation of heterochromatin via multiple mechanisms.

An early study also showed that Paf1C subunits Paf1, Ctr9, and Cdc73 are specifically required for normal H3 K36 trimethylation [14] (Figure 3). This regulation is independent of the H2B K123ub pathway [14] and represses H3 and H4 acetylation over coding regions [14, 80]. This effect is due both to the recruitment of a histone deacetylase complex as well as through inhibition of cotranscriptional exchange of H3, preventing the incorporation of pre-acetylated histones into 5′ coding regions [80]. H3 K36Me3 is generally found in gene bodies and 3′ regions, while H3 K4Me3 dominates the 5′ region [81]. Interestingly, a recent study found that the chromatin remodeler Chd1, which is recruited by Paf1C to actively transcribed genes, helps to establish the normal patterning of both marks, particularly at boundary regions between them [82].

Together, these observations significantly expand the known connections between Paf1C and chromatin structure. Some effects of Paf1C on histone modifications are widely conserved between yeast and humans, while others appear specific to higher eukaryotes. Regardless of the system, the broad impact of Paf1C on histone modification states likely underlies many of the gene expression changes that arise when Paf1C is eliminated or altered by mutation. In humans, the culmination of these changes is likely at the root of numerous diseases.

Paf1C connections to development and human disease

In spite of the diverse and context-dependent functions of Paf1C, its role as a regulator of Pol II transcription is broadly conserved across eukaryotes, and interest in Paf1C has continued to grow as its role in development and human disease has become more evident. Historically, interest was focused on the parafibromin (Cdc73) subunit, a tumor suppressor that, when mutated, can lead to hyperparathyroidism-jaw tumor [83]. More recently, CTR9 was also identified as a tumor suppressor gene in humans, with mutations predisposing to Wilms tumor [24]. Additionally, it was shown that Paf1C is recruited to targets of the p53 tumor suppressor upon transcription stress and is required for their full activation [84]. Paf1C has also been found to promote tumorigenesis in several cell types [25, 26, 85]. In the case of non-small cell lung cancer, Paf1 protein levels correlate negatively with survival, and interestingly, depletion of both Paf1 and c-Myc synergistically inhibited cell proliferation [25].

A role in cancer is consistent with Paf1C regulation of development and differentiation. Paf1C mutants display developmental defects in zebrafish and fruit flies [34, 86–88], and Paf1C is implicated in the maintenance of pluripotency in mouse and human embryonic stem cells (ESCs) [28, 89, 90]. Interestingly, Paf1C regulation of promoter-proximal pausing may underlie its role in these processes. Like Paf1C, the PHD-finger protein Phf5a acts to maintain pluripotency in mouse ESCs [27]. Paf1C binds Phf5a directly, and both Paf1C and Phf5a are downregulated upon differentiation [27]. In the context of pluripotent stem cells, Paf1C and Phf5a appear to cooperate to maintain pluripotency by promoting pause release and thereby productive transcription of genes in the self-renewal network [27]. Paradoxically, H2B K120ub at Paf1C targets increases upon Paf1 depletion in ESCs, while H3 K79Me increases [91]. Furthermore, and consistent with studies in zebrafish [86, 87] and C. elegans [92], both Paf1C and Phf5a are also required for differentiation of myoblasts to myotubules [27], again emphasizing the contextual nature of Paf1C regulation of transcriptional networks.

Concluding Remarks

Since its discovery in budding yeast, the functions attributed to the conserved Paf1C have expanded dramatically as has interest in the ways it regulates gene expression in higher eukaryotes. Moving forward, it will be especially important to identify the detailed mechanisms that control Pol II pausing in metazoans and to clarify why Paf1C imposes pausing in some settings while preventing it in others (see Outstanding Questions Box). It will also be important to elucidate the mechanisms, interplay, and broader consequences of Paf1C’s multiple functions in chromatin modification, transcription elongation control, and post-transcriptional RNA processing and export. A critical challenge yet to be tackled will be the identification of genetic and environmental regulators of Paf1C function and to connect these new discoveries to Paf1C’s many links to human health and development.

Outstanding Questions.

How are the various recruitment mechanisms for Paf1C coordinated and regulated? Does the choice of recruitment strategy differ at different genes?

Is the recruitment of Paf1C to promoters by transcriptional activators a universal mechanism or is it primarily specific to higher eukaryotes?

What genetic features dictate whether Paf1C functions to establish/maintain promoter-proximal Pol II pausing or to stimulate release of paused Pol II?

By what mechanism does Paf1C dictate polyA site selection? Is its role in termination an indirect consequence of its effects on Pol II elongation rates? Or does it regulate the activities of the transcription termination and RNA processing machineries more directly?

Are there additional Paf1C-dependent histone modifications still to be identified?

To what extent do Paf1C-dependent histone modifications explain the diverse effects of Paf1C on gene expression?

What are the higher order effects of Paf1C on genome architecture?

Which Paf1C functions underlie its roles in preventing or promoting human cancers?

Trends.

Paf1C can be recruited to genes by transcriptional activators and through interactions with the Pol II elongation machinery.

Paf1C can function to maintain promoter-proximal pausing of Pol II or to promote release from pausing, depending upon the genetic context.

Paf1C regulates cleavage and polyadenylation of mRNA, governs polyA site selection, and controls the export of nascent transcripts.

Paf1C controls chromatin structure by promoting several co-transcriptional histone modifications and is important for the establishment of proper boundaries between heterochromatin and euchromatin.

Paf1C regulates pluripotency and development in higher eukaryotes, and several new studies link Paf1C misregulation to cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Arndt lab for their valuable advice and critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grant GM052593.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wade PA, et al. A novel collection of accessory factors associated with yeast RNA polymerase II. Protein Expr Purif. 1996;8:85–90. doi: 10.1006/prep.1996.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shi X, et al. Cdc73p and Paf1p are found in a novel RNA polymerase II-containing complex distinct from the Srbp-containing holoenzyme. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1160–1169. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mueller CL, Jaehning JA. Ctr9, Rtf1, and Leo1 are components of the Paf1/RNA polymerase II complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1971–1980. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.7.1971-1980.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costa PJ, Arndt KM. Synthetic lethal interactions suggest a role for the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rtf1 protein in transcription elongation. Genetics. 2000;156:535–547. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.2.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Squazzo SL, et al. The Paf1 complex physically and functionally associates with transcription elongation factors in vivo. EMBO J. 2002;21:1764–1774. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.7.1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rondon AG, et al. Molecular evidence indicating that the yeast PAF complex is required for transcription elongation. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:47–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mueller CL, et al. The Paf1 complex has functions independent of actively transcribing RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell. 2004;14:447–456. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00257-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penheiter KL, et al. A posttranscriptional role for the yeast Paf1-RNA polymerase II complex is revealed by identification of primary targets. Mol Cell. 2005;20:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nordick K, et al. Direct interactions between the Paf1 complex and a cleavage and polyadenylation factor are revealed by dissociation of Paf1 from RNA polymerase II. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:1158–1167. doi: 10.1128/EC.00434-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ng HH, et al. The Rtf1 component of the Paf1 transcriptional elongation complex is required for ubiquitination of histone H2B. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33625–33628. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300270200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wood A, et al. The Paf1 complex is essential for histone monoubiquitination by the Rad6-Bre1 complex, which signals for histone methylation by COMPASS and Dot1p. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34739–34742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300269200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng HH, et al. Targeted recruitment of Set1 histone methylase by elongating Pol II provides a localized mark and memory of recent transcriptional activity. Mol Cell. 2003;11:709–719. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krogan NJ, et al. The Paf1 complex is required for histone H3 methylation by COMPASS and Dot1p: linking transcriptional elongation to histone methylation. Mol Cell. 2003;11:721–729. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu Y, et al. Regulation of histone modification and cryptic transcription by the Bur1 and Paf1 complexes. EMBO J. 2007;26:4646–4656. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen FX, et al. PAF1, a Molecular Regulator of Promoter-Proximal Pausing by RNA Polymerase II. Cell. 2015;162:1003–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu M, et al. RNA polymerase II-associated factor 1 regulates the release and phosphorylation of paused RNA polymerase II. Science. 2015;350:1383–1386. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu X, et al. Multiple P-TEFbs cooperatively regulate the release of promoter-proximally paused RNA polymerase II. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:6853–6867. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Y, et al. PAF Complex Plays Novel Subunit-Specific Roles in Alternative Cleavage and Polyadenylation. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1005794. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kowalik KM, et al. The Paf1 complex represses small-RNA-mediated epigenetic gene silencing. Nature. 2015;520:248–252. doi: 10.1038/nature14337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sadeghi L, et al. The Paf1 complex factors Leo1 and Paf1 promote local histone turnover to modulate chromatin states in fission yeast. EMBO Rep. 2015;16:1673–1687. doi: 10.15252/embr.201541214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verrier L, et al. Global regulation of heterochromatin spreading by Leo1. Open Biol. 2015:5. doi: 10.1098/rsob.150045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu L, et al. The RING finger protein MSL2 in the MOF complex is an E3 ubiquitin ligase for H2B K34 and is involved in crosstalk with H3 K4 and K79 methylation. Mol Cell. 2011;43:132–144. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newey PJ, et al. Parafibromin--functional insights. J Intern Med. 2009;266:84–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanks S, et al. Germline mutations in the PAF1 complex gene CTR9 predispose to Wilms tumour. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4398. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhi X, et al. Human RNA polymerase II associated factor 1 complex promotes tumorigenesis by activating c-MYC transcription in non-small cell lung cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;465:685–690. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moniaux N, et al. The human homologue of the RNA polymerase II-associated factor 1 (hPaf1), localized on the 19q13 amplicon, is associated with tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2006;25:3247–3257. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strikoudis A, et al. Regulation of transcriptional elongation in pluripotency and cell differentiation by the PHD-finger protein Phf5a. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:1127–1138. doi: 10.1038/ncb3424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ding L, et al. A genome-scale RNAi screen for Oct4 modulators defines a role of the Paf1 complex for embryonic stem cell identity. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:403–415. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu B, et al. The human PAF complex coordinates transcription with events downstream of RNA synthesis. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1668–1673. doi: 10.1101/gad.1292105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mbogning J, et al. The PAF complex and Prf1/Rtf1 delineate distinct Cdk9-dependent pathways regulating transcription elongation in fission yeast. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1004029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao QF, et al. Characterization of the Human Transcription Elongation Factor Rtf1: Evidence for Nonoverlapping Functions of Rtf1 and the Paf1 Complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;35:3459–3470. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00601-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Betz JL, et al. Phenotypic analysis of Paf1/RNA polymerase II complex mutations reveals connections to cell cycle regulation, protein synthesis, and lipid and nucleic acid metabolism. Mol Genet Genomics. 2002;268:272–285. doi: 10.1007/s00438-002-0752-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mosimann C, et al. Parafibromin/Hyrax activates Wnt/Wg target gene transcription by direct association with beta-catenin/Armadillo. Cell. 2006;125:327–341. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bahrampour S, Thor S. Ctr9, a Key Component of the Paf1 Complex Affects Proliferation and Terminal Differentiation in the Developing Drosophila Nervous System. G3 (Bethesda) 2016;6:3229–3239. doi: 10.1534/g3.116.034231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim J, et al. The human PAF1 complex acts in chromatin transcription elongation both independently and cooperatively with SII/TFIIS. Cell. 2010;140:491–503. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chu X, et al. Structural insights into Paf1 complex assembly and histone binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:10619–10629. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Oss SB, et al. The Histone Modification Domain of Paf1 Complex Subunit Rtf1 Directly Stimulates H2B Ubiquitylation through an Interaction with Rad6. Mol Cell. 2016;64:815–825. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mayer A, et al. Uniform transitions of the general RNA polymerase II transcription complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1272–1278. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zaborowska J, et al. The pol II CTD: new twists in the tail. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:771–777. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amrich CG, et al. Cdc73 subunit of Paf1 complex contains C-terminal Ras-like domain that promotes association of Paf1 complex with chromatin. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:10863–10875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.325647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qiu H, et al. Pol II CTD kinases Bur1 and Kin28 promote Spt5 CTR-independent recruitment of Paf1 complex. EMBO J. 2012;31:3494–3505. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Y, et al. Phosphorylation of the transcription elongation factor Spt5 by yeast Bur1 kinase stimulates recruitment of the PAF complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:4852–4863. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00609-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mayekar MK, et al. The recruitment of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Paf1 complex to active genes requires a domain of Rtf1 that directly interacts with the Spt4–Spt5 complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:3259–3273. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00270-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wier AD, et al. Structural basis for Spt5-mediated recruitment of the Paf1 complex to chromatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:17290–17295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314754110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Laribee RN, et al. BUR kinase selectively regulates H3 K4 trimethylation and H2B ubiquitylation through recruitment of the PAF elongation complex. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1487–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu Y, et al. Architecture of the RNA polymerase II-Paf1C-TFIIS transcription elongation complex. Nat Commun. 2017:8. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jaenicke LA, et al. Ubiquitin-Dependent Turnover of MYC Antagonizes MYC/PAF1C Complex Accumulation to Drive Transcriptional Elongation. Mol Cell. 2016;61:54–67. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fonseca GJ, et al. Adenovirus E1A recruits the human Paf1 complex to enhance transcriptional elongation. J Virol. 2014;88:5630–5637. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03518-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fonseca GJ, et al. Viral retasking of hBre1/RNF20 to recruit hPaf1 for transcriptional activation. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003411. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kikuchi I, et al. Dephosphorylated parafibromin is a transcriptional coactivator of the Wnt/Hedgehog/Notch pathways. Nat Commun. 2016:7. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takahashi A, et al. SHP2 tyrosine phosphatase converts parafibromin/Cdc73 from a tumor suppressor to an oncogenic driver. Mol Cell. 2011;43:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pokholok DK, et al. Exchange of RNA polymerase II initiation and elongation factors during gene expression in vivo. Mol Cell. 2002;9:799–809. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00502-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krogan NJ, et al. RNA polymerase II elongation factors of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a targeted proteomics approach. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6979–6992. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.20.6979-6992.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adelman K, Lis JT. Promoter-proximal pausing of RNA polymerase II: emerging roles in metazoans. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:720–731. doi: 10.1038/nrg3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu X, et al. Ready, pause, go: regulation of RNA polymerase II pausing and release by cellular signaling pathways. Trends Biochem Sci. 2015;40:516–525. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu L, et al. H2B ubiquitylation promotes RNA Pol II processivity via PAF1 and pTEFb. Mol Cell. 2014;54:920–931. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.He N, et al. Human Polymerase-Associated Factor complex (PAFc) connects the Super Elongation Complex (SEC) to RNA polymerase II on chromatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:E636–645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107107108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bartkowiak B, et al. CDK12 is a transcription elongation-associated CTD kinase, the metazoan ortholog of yeast Ctk1. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2303–2316. doi: 10.1101/gad.1968210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maniatis T, Reed R. An extensive network of coupling among gene expression machines. Nature. 2002;416:499–506. doi: 10.1038/416499a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Proudfoot NJ, et al. Integrating mRNA processing with transcription. Cell. 2002;108:501–512. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00617-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jonkers I, Lis JT. Getting up to speed with transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:167–177. doi: 10.1038/nrm3953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ahn SH, et al. Phosphorylation of serine 2 within the RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain couples transcription and 3′ end processing. Mol Cell. 2004;13:67–76. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00492-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Licatalosi DD, et al. Functional interaction of yeast pre-mRNA 3′ end processing factors with RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1101–1111. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00518-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rozenblatt-Rosen O, et al. The tumor suppressor Cdc73 functionally associates with CPSF and CstF 3′ mRNA processing factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:755–760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812023106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nagaike T, et al. Transcriptional activators enhance polyadenylation of mRNA precursors. Mol Cell. 2011;41:409–418. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fischl H, et al. Paf1 Has Distinct Roles in Transcription Elongation and Differential Transcript Fate. Mol Cell. 2017;65:685–698. e688. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Battaglia S, et al. RNA-dependent chromatin association of transcription elongation factors and Pol II CTD kinases. Elife. 2017;6:e25637. doi: 10.7554/eLife.25637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fierz B, et al. Histone H2B ubiquitylation disrupts local and higher-order chromatin compaction. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:113–119. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Batta K, et al. Genome-wide function of H2B ubiquitylation in promoter and genic regions. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2254–2265. doi: 10.1101/gad.177238.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mutiu AI, et al. The role of histone ubiquitylation and deubiquitylation in gene expression as determined by the analysis of an HTB1(K123R) Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain. Mol Genet Genomics. 2007;277:491–506. doi: 10.1007/s00438-007-0212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shema E, et al. The histone H2B-specific ubiquitin ligase RNF20/hBRE1 acts as a putative tumor suppressor through selective regulation of gene expression. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2664–2676. doi: 10.1101/gad.1703008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang X, et al. Transcriptional regulation by Lge1p requires a function independent of its role in histone H2B ubiquitination. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2759–2770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408333200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Warner MH, et al. Rtf1 is a multifunctional component of the Paf1 complex that regulates gene expression by directing cotranscriptional histone modification. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:6103–6115. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00772-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Piro AS, et al. Small region of Rtf1 protein can substitute for complete Paf1 complex in facilitating global histone H2B ubiquitylation in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:10837–10842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116994109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fuchs G, et al. Cotranscriptional histone H2B monoubiquitylation is tightly coupled with RNA polymerase II elongation rate. Genome Res. 2014;24:1572–1583. doi: 10.1101/gr.176487.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sanso M, et al. A positive feedback loop links opposing functions of P-TEFb/Cdk9 and histone H2B ubiquitylation to regulate transcript elongation in fission yeast. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002822. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Su J, et al. The Functional Analysis of Histone Acetyltransferase MOF in Tumorigenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2016:17. doi: 10.3390/ijms17010099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Allshire RC, Ekwall K. Epigenetic Regulation of Chromatin States in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015;7:a018770. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a018770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang J, et al. Epe1 recruits BET family bromodomain protein Bdf2 to establish heterochromatin boundaries. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1886–1902. doi: 10.1101/gad.221010.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Venkatesh S, Workman JL. Set2 mediated H3 lysine 36 methylation: regulation of transcription elongation and implications in organismal development. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2013;2:685–700. doi: 10.1002/wdev.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Smolle M, Workman JL. Transcription-associated histone modifications and cryptic transcription. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1829:84–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee Y, et al. The ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler Chd1 is recruited by transcription elongation factors and maintains H3K4me3/H3K36me3 domains at actively transcribed and spliced genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang PF, et al. HRPT2, a tumor suppressor gene for hyperparathyroidism-jaw tumor syndrome. Horm Metab Res. 2005;37:380–383. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Albert TK, et al. The Establishment of a Hyperactive Structure Allows the Tumour Suppressor Protein p53 to Function through P-TEFb during Limited CDK9 Kinase Inhibition. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0146648. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Karmakar S, et al. hPaf1/PD2 interacts with OCT3/4 to promote self-renewal of ovarian cancer stem cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:14806–14820. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Langenbacher AD, et al. The PAF1 complex differentially regulates cardiomyocyte specification. Dev Biol. 2011;353:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nguyen CT, et al. The PAF1 complex component Leo1 is essential for cardiac and neural crest development in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2010;341:167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Akanuma T, et al. Paf1 complex homologues are required for Notch-regulated transcription during somite segmentation. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:858–863. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rigbolt KT, et al. System-wide temporal characterization of the proteome and phosphoproteome of human embryonic stem cell differentiation. Sci Signal. 2011;4:rs3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ponnusamy MP, et al. RNA polymerase II associated factor 1/PD2 maintains self-renewal by its interaction with Oct3/4 in mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:3001–3011. doi: 10.1002/stem.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Strikoudis A, et al. Opposing functions of H2BK120 ubiquitylation and H3K79 methylation in the regulation of pluripotency by the Paf1 complex. Cell Cycle. 2017 doi: 10.1080/15384101.2017.1295194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Trappe R, et al. The Caenorhabditis elegans ortholog of human PHF5a shows a muscle-specific expression domain and is essential for C. elegans morphogenetic development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297:1049–1057. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]