Summary

Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) are a growing family of immune cells that mirror the phenotypes and functions of T cells. However, in contrast to T cells, ILCs do not express acquired antigen receptors or undergo clonal selection and expansion when stimulated. Instead, ILCs react promptly to signals from infected or injured tissues and produce an array of secreted proteins termed cytokines that direct the developing immune response into one that is adapted to the original insult. The complex crosstalk between microenvironment, ILCs and adaptive immunity remains to be fully deciphered. Only by understanding these complex regulatory networks can the power of ILCs be controlled or unleashed to regulate or enhance immune responses in disease prevention and therapy.

Introduction

What are innate lymphoid cells?

During hematopoiesis, the common lymphoid progenitor (CLP) gives rise to antigen receptor-bearing T and B lymphocytes. Until quite recently, only two types of lymphoid cells had been recognised as deriving from CLPs but devoid of any antigen receptors. The first of these cells were the natural killer (NK) cells that complement the cytotoxic CD8+ T cells in killing infected, stressed or transformed cells (1). The second were lymphoid tissue inducer (LTi) cells, which induce the development of lymph nodes and Peyer’s patches (2, 3). However since 2008 the world of lymphoid cells has expanded dramatically. LTi-like cells were found that also express markers associated with NK cells, and were termed NK22 cells or natural cytotoxicity receptor 22 (NCR22) cells for their concomitant expression of the cytokine interleukin (IL)-22 (4–7). Natural helper cells and nuocytes were described that expand in response to helminth infection and promote anti-worm and pro-allergic type 2 immune responses (8, 9). Finally, non-cytotoxic NK-like cells were isolated from the intestinal epithelium (10, 11). To avoid chaos in diversity, it was decided to reunite all these cells into one family of “innate lymphoid cells”, or ILCs, and to create three categories of ILC1s, ILC2s and ILC3s that reflect the cytokine expression profiles of the classical CD4+ T helper (Th) cell subsets Th1, Th2 and Th17 cells (12).

ILCs share the developmental origin and many of the phenotypes and functions of T cells. However, ILCs are activated by stress signals, microbial compounds and the cytokine milieu of the surrounding tissue, rather than by antigen, in ways similar to the activation of memory or “innate” T cells, such as invariant NKT cells and subsets of γδ T cells. This mode of activation makes ILCs highly reactive and early effectors during the immune response. Furthermore, ILCs express the effector cytokines normally associated with T helper cells, and therefore, ILCs are expected to play a central role in the regulation of type 1, type 2 and type 3 (or Th17 cell) responses, which control intracellular pathogens, large parasites and extracellular microbes, respectively. The activity of ILCs may thus be harnessed to enhance responses against pathogens and tumors, during vaccination and immunotherapy, or inhibited to prevent autoimmune or allergic inflammation. Recent data also show that the role of ILCs extends beyond immunity into physiology through the regulation of fat metabolism and body temperature (13–15). In this review, we discuss these intriguing issues in the light of the most recent developments.

Development and evolution of ILCs

Developing away from adaptive lymphocyte fate

ILCs develop from CLPs that give rise to B cell and T cell precursors, NK cell precursors (NKP) and the recently described common helper ILC precursors (ChILP) that express Id2 and variable levels of PLZF (Figure 1) (16–18). ChILPs generate all ILC groups but not NK cells, while PLZF+ ILC precursors generate all ILC groups but not NK cells or LTi cells. ILC development from CLP (via NKP or ChILP) therefore involves a stage of lineage restriction, where B and T cell potentials are lost and ILC potential is reinforced. This is achieved through coordinated expression of specific transcription factors that activate or repress target genes that are critical for subset-specific lymphocyte differentiation. For ILC development, several transcription factors have been shown to be critical at the ILC precursor stage, including Id2, Nfil3 and Gata3 (19–24). Our understanding of how these transcription factors promote ILC fate is incomplete, but one emerging concept involves obligate suppression of alternative lymphoid cell fates, based on reciprocal repression as a means to control binary cell fate decisions. Id2 is a transcriptional repressor that acts to reduce the activity of E-box transcription factors (E2A, E2-2, HEB), critical in early B and T cell development. Thus, increasing expression of Id2 in CLP promotes ILC development at the expense of the B and T cell fates (20, 25). Accordingly, NKP and ChILP express variable levels of Id2, whereas CLP do not express Id2 (16, 26). In a similar fashion, Gata3 represses B cell fate by blocking EBF1 and thereby facilitates T and ILC differentiation from CLPs (23, 24, 27).

Figure 1. The development of ILCs.

The development of ILCs from common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) requires Id2-mediated suppression of alternative lymphoid cell fates that generate B and T cells. Factors present in the microenvironment, such as Notch ligands, bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs) and cytokines, as well as the circadian rhythm, control expression of Nfil3, Gata3 and Id2, which determine the progression towards the ILC fate. Distinct precursors give rise to NK cells and ILCs (which, unlike NK cells, are non-cytotoxic), while the transcription factor PLZF further divides the progeny of ChILPs into the PLZF-dependent ILC1s, ILC2s and ILC3s, and PLZF-independent LTi cells (although LTi cells tend to be grouped as ILC3s) required for the development of lymph nodes, Peyer’s patches and ILFs. The maturation of ILC precursors into mature ILCs may occur outside of primary lymphoid tissues, in ways similar to the maturation of naïve T helper cells into Th1, Th2, Th17 and Treg cells, and in response to a variety of signals produced by the tissue microenvironment.

How Id2 or Gata3 expression is controlled as CLPs differentiate into NKP or ChILP is not fully understood. Signals produced by the microenvironment, for example bone morphogenic proteins (BMP) and Notch ligands (28, 29), regulate Id2 expression, a mechanism that could apply to CLPs. Furthermore, the transcription factor Nfil3 links the peripheral circadian clocks involving the nuclear receptor Rev-ERBα to gene regulation (30), and its deletion impacts on multiple developmental processes within the hematopoietic system. In particular, Nfil3 controls differentiation of ILC via Id2 and the transcription factors RORγt, Eomesodermin and Tox (21, 22, 31). In addition, soluble factors including cytokines, regulate Nfil3 expression (32), thereby providing a link between signals from the tissue and fate decisions into the ILC lineages.

Do ILCs complete development in response to local cues?

Conventional wisdom suggests that the primary site of ILC development is the liver in the fetus, and the bone marrow after birth, as these primary lymphoid organs harbour CLP, NKP and ChILP (16, 33, 34). Once generated, mature ILCs exit these sites, circulate in the blood and enter tissues following codes based on adhesion molecules and chemokines, similar to the ones used by T cells. This model is supported by the dearth of tissue-resident ILCs under steady-state conditions, with the exception of mucosal sites, and the rapid recruitment of ILCs following infection or injury. However, ILC precursors, the NKP and the ChILP, may leave the fetal liver or the bone marrow and complete their maturation in response to local signals, much in the same way as naïve T cells differentiate into the different effector subsets during inflammation. In this view, ILC precursors would be the innate homologues of naïve T cells.

In support of this hypothesis, NKP and ILC3 precursors are found in human tonsils (35). In mouse, ILC3 precursors are found in the fetal gut (19) where their mature progeny induce the development of Peyer’s patches, as well as after birth in the lamina propria of the small intestine (36). Notably, fetal ILC precursors with the capacity to give rise to ILC1s, ILC2s and ILC3s are present in the mouse intestine and accumulate in the developing Peyer’s patches (37). The vitamin A metabolite retinoic acid (RA), produced by many types of cells outside lymphoid organs, including nerve cells (38), dendritic cells (DCs) (39) and stromal cells (40), favours the maturation of ILC3s at the expense of ILC2s (41), and is required for the full maturation of ILC3s in the fetus and the adult (42). Furthermore, although IL-25 and IL-33 produced by epithelial cells both promote ILC2 differentiation, it has been proposed that IL-25 may act to expand precursors that retain ILC3 potential (43). Finally, the aryl hydrocarbon receptor Ahr, which is triggered by ligands from diet, is also required for the maintenance and expansion of intestinal ILC3s after birth (44–46).

ILCs as evolutionary precursors to T cells

Even though the adaptive lymphocyte fate has to be blocked in CLPs to generate ILCs, striking similarities exist between ILC and T cell differentiation. Gata3, Nfil3 and Tcf1 (21–24, 47, 48) are shared by the precursor common to T cells and ILCs, and the signature transcription factors T-bet, Gata3 and RORγt, which determine the development of type 1, 2 or 3 cells, are highly conserved in both innate and adaptive lymphoid cells, in mice and men. It is therefore tempting to propose that ILCs are the evolutionary precursors of T cells, even though definitive evidence has yet to be found that ILCs exist in invertebrates or early vertebrates that lack T or B lymphocytes (49). The emergence of ILCs, and thus of the lymphoid lineage, must also have provided a fitness advantage. As we now understand the function of ILCs and T helper cells, this advantage would build on the ability to rapidly direct immunity into type 1, type 2 or type 3 responses that are adapted to counter specific types of threats. Myeloid cells, as well as non-hematopoietic cells such as epithelial cells and stromal cells, produce cytokines in reaction to infection and injury, which activate a particular ILC subset and the production of effector cytokines. The reason why phagocytic myeloid cells, presumably the first type of immune cells to appear during evolution, would not perform this function is unclear, but may be related to the superior capacity of lymphoid cells to expand rapidly.

Once established as a diverse family of innate effector cells, the program of ILC development, differentiation and function would serve as a ‘blueprint’ for T cells. Emergence of the adaptive arm of the immune system, based on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) restriction and somatic rearrangements of antigen receptor genes, would be layered onto the ILC program, providing an exhaustive range of antigen specificity to the already existing effector cell diversity. Since clonal selection via the T cell receptor results in substantial cellular expansion, T cells may also be freed from the micro-environmental constraints that limit ILC expansion, thereby providing more amplitude to immune effector and regulatory functions, as well as antigen-specific immunological memory.

Activation of ILCs

ILCs translate signal cytokines into effector cytokines

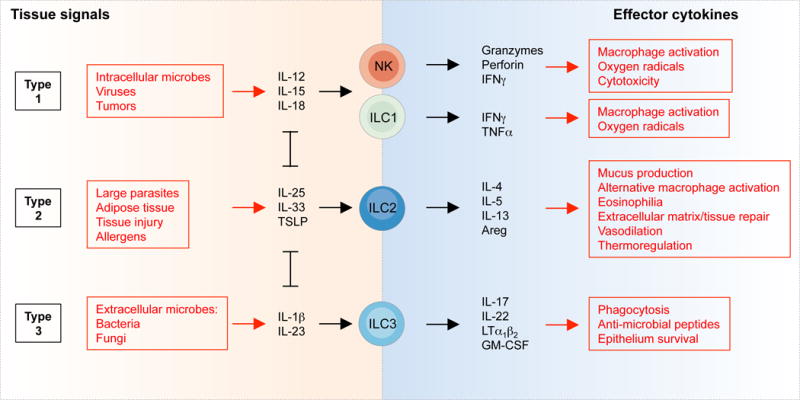

In the absence of adaptive antigen receptors, ILCs react to the microenvironment through cytokine receptors. NK cells and ILC1s expand and secrete interferon (IFN)γ in response to IL-12, IL-15 and IL-18 produced by myeloid cells as well as by non-hematopoietic cells in response typically to intracellular pathogens (Figure 2) (10, 11, 16, 50). ILC2s, on the other hand, respond to the epithelium-derived cytokines IL-25, IL-33, TSLP (thymic stroma lymphopoietin), basophil-derived IL-4 and products of the arachidonic acid pathway, in response to parasite infection, allergens and epithelial injury (8, 9, 51–53). Activation of ILC2s leads to the production of high amounts of IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13. Finally, ILC3s respond mainly to IL-1β and IL-23 produced by myeloid cells in response to bacterial and fungal infection (54–56). ILC3s produce lymphotoxins, GM-CSF (granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor) and IL-22, as well as IL-17 in the fetus, early after birth and during inflammation (57, 58).

Figure 2. Activation and functions of ILCs.

The tissue signals that expand and activate ILC1s, ILC2s and ILC3s, and the effector functions of ILCs, mirror the activation and functions of T cells. In this figure, NK cells, ILC1s, ILC2s and ILC3s could be replaced by CD8+ T cells, Th1, Th2 and Th17 cells, respectively. However, while ILCs are activated promptly by tissue signals and therefore act upstream in the immune response, T cells are first selected and expanded on the basis of T cell receptor specificity, a process that typically requires several days.

Thus, ILCs translate signal cytokines produced by myeloid and non-hematopoietic cells in tissues into effector cytokines that activate local innate and adaptive effector functions. For example, IFNγ activates the production of microbicidal reactive oxygen species in myeloid cells, induces the production of antibodies for antibody-mediated cytotoxicity and increases antigen presentation by MHC molecules (59). On the other hand, IL-5 and IL-13 induce the production of mucus by goblet cells (the secretion of which can also be induced by IFNγ (60)), the production of IgE and the recruitment of eosinophils (61), while IL-17 and IL-22 induce the production of anti-microbial peptides by epithelial cells (62) and the recruitment of neutrophils through the expression of CXC chemokines by stromal cells (63).

NK cells also express an array of receptors that recognize MHC I, the constant domains of antibodies and cell surface molecules associated with cellular transformation, stress and infection, the activation of which leads to cytotoxicity and the production of IFNγ (64). These NK receptors are not antigen receptors, but nevertheless confer some degree of specificity to the reactivity of NK cells. Interestingly, as individual NK cells express different combinations and levels of NK receptors, triggering of one receptor may lead to the expansion of a subset of NK cells and thus to an increased response, or memory, upon re-encounter of the trigger (65). Furthermore, a subset of ILC3s expresses the pan-NK marker NKp46 in mouse and NKp44 in human (4–7). NKp46 appears redundant for ILC3 responses against bacterial infection (66), but NKp44 can activate human ILC3s (67). Finally, ILCs isolated from human tonsils were found to produce IL-5 and IL-13, as well as IL-22, in response to ligands that bind the pattern recognition receptor Toll like receptor 2 (TLR2) (68), indicating that ILCs may also react to microbial compounds. Thus, it is possible that ILCs express different arrays of innate receptors that enable them to react to sets of molecules or proxies for type 1, type 2 or type 3-inducing cellular stresses, injuries or infections. However, while such receptors are well studied for NK cells, they remain to be described for the other types of ILCs.

How diet and the microbiota influence ILC development and activity

As mentioned earlier, the vitamin A metabolite retinoic acid (RA) is required for full maturation of ILC3s at the expense of ILC2s (41, 42), and food-derived Ahr ligands are required for the maintenance of ILC3s after birth (44–46). Furthermore, TLR2 ligands can activate human ILC2s and ILC3s in vitro (68). That is, however, the state of our knowledge of the direct effects of diet and microbiota on ILCs. In contrast, much more is known on indirect effects of diet and microbes on the activation of ILCs.

In the absence of microbiota in germfree mice, the activity of ILC3s in the intestine is significantly perturbed. While the development of lymph nodes and Peyer’s patches, induced by LTi cells, is programed in the fetus, the formation of isolated lymphoid follicles (ILFs) in the intestinal lamina propria after birth is not (69). Bacteria are required to trigger the production of β-defensins and the chemokine CCL20 by epithelial cells, which induce the morphogenesis of ILFs through activation of CCR6+ LTi cells clustered in so-called cryptopatches (70), and the recruitment of CCR6+ B cells to nascent ILFs (71). The B cell chemoattractant CXCL13, produced by dedicated stromal cells termed “lymphoid stromal cells” (LSC), is also required for the development of lymphoid tissues through the recruitment of LTi cells from the bloodstream (72), and is induced by RA (38). Furthermore, microbiota induce the expression of CXCL16 by dendritic cells (DCs), which recruits ILC3s to the lamina propria and villi of the small intestine (73). Microbiota also negatively regulate the activity of ILC3s. The expression of IL-17 and IL-22 by ILC3s is highest in the fetus and gradually declines after birth as the intestinal tract is colonized. Microbiota induce the expression of the type 2 cytokine IL-25 by epithelial cells, which activates IL25R+ DCs and the regulation of ILC3s through mechanisms that remain to be elucidated (57).

High fat diet leads to the build-up of visceral adipose tissue (VAT). Intriguingly, ILC2s are associated with VAT (74) and were originally described as residents of “fat-associated lymphoid clusters” (FALC) on the mesentery (8). The production of IL-5 and IL-13 by ILC2s leads to the recruitment of eosinophils and the generation of alternatively activated macrophages (AAM) that protect the organism from fat-induced ILC3-mediated inflammatory pathology (74, 75). It is unclear how fat tissue regulates the activation of ILC2s or ILC3s, but this possibly involves metabolites of arachidonic acid, such as prostaglandins and lipoxins, which are respectively activators and inhibitors of ILC2s (76).

Roles of ILCs in immunity

Do ILCs have unique effector functions?

Each cell type in an organism is expected to have a unique function that justifies its evolutionary conservation. However, NK cells, ILC1s, ILC2s and ILC3s mirror the cytokine production and effector functions of CD8+ T cells, Th1, Th2 and Th17 cells (Figure 2). Nevertheless, in contrast to T cells, ILCs do not undergo antigen-driven clonal selection and expansion, and therefore, ILCs act promptly like a population of memory T cells. As a consequence, within hours after infection or injury, the effector cytokines IFNγ, IL-5 and IL-13, or IL-17 and IL-22, which can be produced by both ILCs and T cells, are produced mostly by ILCs. In certain tissues, the prompt production of effector cytokines is shared with “innate” T cells, such as mucosa-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells that produce IFNγ, IL-17 and IL-22 (77), invariant NKT (iNKT) cells that produce IFNγ or IL-4 (78), and subsets of γδ T cells that produce IFNγ and IL-17 within different epithelial and mucosal compartments (79–81). Nevertheless, each of these cell types reacts to distinct stimuli. For example MAIT cells recognize microbial metabolites bound to the MHC-like molecule MR1, and iNKT cells respond to glycolipid moieties bound to the MHC-like molecule CD1d.

Regulation of adaptive immunity by ILCs

As ILCs are activated early in the immune response to infection and injury, and produce type 1, type 2 and type 3 cytokines, it is expected that they regulate the developing adaptive immune response (82). ILCs have been found to do that in two ways: directly through the expression of MHC class II molecules (MHC II), and indirectly through the regulation of DCs (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Regulation of adaptive immunity by ILCs.

ILCs regulate T cells both directly through antigen presentation on MHC II, and indirectly through the regulation of DCs. The crosstalk between ILCs, DCs and T cells establishes a complex regulatory network, involving positive and negative feedbacks, the dynamics of which remain to be elucidated. The mechanisms by which ILCs repress CD4+ T helper (Th) cell activation remain unclear, but may involve the lack of costimulatory molecules in the context of steady-state (84). It also remains unclear how DCs negatively regulate the activity of ILCs (57). Red lines depict feedback loops, and A, B and C list the type 1, type 2 or type 3 cytokines involved in a specific crosstalk. ILC3s also activate B cells in the intestine through lymphotoxin-mediated recruitment of T helper cells and activation of dendritic cells (91), as well as marginal zone B cells in the spleen (132).

ILC3s were shown nearly two decades ago to express MHC II on their surface (2, 83), but the significance of this expression became clear only recently. ILC3s not only express MHC II, but also transcripts for molecules associated with antigen processing and presentation, such as the invariant chain CD74 and the catalyser of peptide exchange H2-DM, and can process exogenous antigen for presentation to CD4+ T cells (84). In the intestine, ILC3s regulate the activity of T cells specific for microbiota-derived antigens, and as a consequence, the absence of MHC II on ILC3s leads to intestinal inflammation. In contrast, ILC3s were shown to activate CD4+ T cells in the spleen upon antigen processing and presentation on MHC II (85). ILC2s also present antigen on MHC II and induce the production of IL-2 and IL-4 by CD4+ T cells, which drive a positive feedback on growth and cytokine production by ILC2s expressing the receptors for IL-2 and IL-4 (86, 87). This dialogue is functionally important as MHC II-deficient ILC2s fail to cause efficient expulsion of parasitic helminths, even in the presence of MHC II+ DCs (86).

ILCs also regulate DCs. The production of IFNγ by NK cells increases the production of IL-12, IL-15 and IL-18 by DCs, driving a positive feedback loop between NK cells and DCs that promotes the differentiation of Th1 cells (88). Likewise, the production of IL-13 by ILC2s leads to the activation of DCs, their migration into the draining lymph nodes and the differentiation of Th2 cells (89). In the absence of ILC2s, the levels of IL-13 are insufficient to instigate the migration of DCs to the lymph nodes in response to lung injury and Th2 responses are impaired (89). Finally, ILC3s activate DCs through membrane-bound lymphotoxin (LT) α1β2, which in turn produce elevated levels of IL-23 that promotes the activity of ILC3s and the differentiation of Th17 cells (90), as well as nitric oxide that activates B cells (91).

As ILCs promote T cell activation through DCs, it is likely that T cells promote ILC activation through similar mechanisms, establishing positive feedback loops between ILC, T cells and DCs. However, this crosstalk also provides controls on the activity of ILCs, as a decrease in the source of T cell antigen and of signals from the affected tissue should exhaust the positive feedback. In addition, competition between ILC and T cells for common activating cytokines from DCs and the affected tissue may also regulate ILC activity. In agreement with this hypothesis, the activity of ILC3s is increased in the absence of T cells (57). Furthermore, the dependence of ILC2s on IL-2 raises the possibility that both ILC2s and T cells are regulated by regulatory T cells through the removal of IL-2 from the micro-environment.

ILCs in tissue protective and repair responses

ILC2s are involved in tissue repair responses through the production of amphiregulin (a ligand of the epidermal growth factor receptor) and IL-13. Upon infection of mouse lungs with the H1N1 influenza virus, ILC2s contribute to tissue repair through the expression of amphiregulin (92). Furthermore, injury to the bile duct, which can lead to severe liver disease, leads to the IL-33-mediated activation of ILC2s that promote cholangiocyte proliferation and epithelial restoration through the release of IL-13 (93). In VAT, IL-13 production by ILC2s protects from fat-induced inflammation promoted by ILC3s, which leads to metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance and diabetes (74). More generally, IL-13 leads to the recruitment of eosinophils and the generation of AAMs (75), and promotes the production of extracellular matrix by stroma cells and mucus by epithelial cells, mechanisms involved both in repair responses and in defence against large parasites (94).

ILC3s promote tissue protective and repair responses through the production of LTα1β2 and IL-22. Infection of lymph nodes with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus leads to the destruction of lymphoid stromal cells (LSC). ILC3s restore LSCs through LTα1β2 and activation of LTβ receptor on LSCs (95). IL-22 has a general role in protecting epithelial cells, mostly through the activation of anti-apoptotic pathways. In a model of graft versus host disease (GvHD), ILC3s protect intestinal epithelial stem cells from GvHD-induced cell death (96). In that context, a subset of ILC3s resists full body irradiation and provides IL-22 to the stem cells. A similar ILC3-mediated mechanism was found to protect the thymus from the consequences of total body irradiation (97). IL-22 also protects hepatocytes from acute liver inflammation, but the source of IL-22 was, at the time, attributed to Th17 cells (98). The source of IL-22 was later recognized to include ILC3s in the CD45RA+ cell transfer model of colitis (99).

ILCs and fat: roles beyond immunity?

Adipose tissue is associated with the immune system at several levels. Lymph nodes and lymphoid clusters on the mesentery are embedded in adipose tissue for reasons that remain unclear (8). Type 2 responses, including ILC2s, are required to avoid the induction of type 3 responses that lead to metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, diabetes as well as to obesity-associated asthma (100). In contrast, high fat diet increases gut permeability and leads to the accumulation of bacteria in VAT, the recruitment and activation of type 1 macrophages and a shift of the immune response associated with VAT from a protective type 2 to a pathogenic type 3 response (101, 102). Furthermore, ILC2s have recently been shown to regulate thermogenesis from beige fat in a process that appears to involve immune cells beyond immunity (13–15). The sensing of cold by nerves triggers their release of catecholamines that activate the biogenesis and activation of brown adipose tissue (BAT) for thermogenesis. Subcutaneous white adipose tissue (scWAT) can also undergo browning under these circumstances, but its low innervation cannot provide the levels of catecholamines required for the conversion of scWAT into beige fat. Macrophages, however, are recruited to cold-stressed scWAT and produce catecholamines, thereby amplifying the signals released by nerves. This activity of macrophages is dependent on IL-4 produced by eosinophils, as well as on IL-5 and IL-13 produced by ILC2s, replicating the recruitment and activation process induced by ILC2s in VAT. ILC2s also produce methionine-enkephalin peptides, which induce beiging of VAT (15). Finally, IL-4 and IL-13 induce the differentiation of adipocyte precursors directly into beige fat (14).

ILCs in pathology

High frequencies of ILC1s are found in Crohn’s disease patients and in mouse models of colitis, contributing to the pathology through the production of IFNγ (10, 11). ILC3s are also associated with inflammatory pathology when producing both IL-17 and IFNγ during colitis and infection with Salmonella enterica (56, 103), as well as with obesity-induced airway hyperreactivity through the production of IL-17 (Figure 4) (100). Furthermore, the pathogenicity of ILC3s was demonstrated when comparing mice deficient in T and B cells only with those lacking T cells, B cells and ILCs (56). These studies show that ILC3s can be pathogenic (or sufficient to induce pathology), but nevertheless fail to show that ILC3s are necessary for the development of pathology in the presence of adaptive immunity. The difficulty stems from the lack of mutant mice that lack ILC1s or ILC3s while developing a normal set of Th1 or Th17 cells. A chimera system has been established to partially alleviate this difficulty (104). In this system, mature T and B cells are adoptively transferred into Rag-deficient mice, which lack these cell types but develop ILCs. Antibody depletion against a congenic marker depletes ILCs but leaves the T cell compartment intact.

Figure 4. ILCs in pathology.

Pathogens, allergens, chemicals, diet, metabolic states and genetic factors can induce type 1, type 2 or type 3 inflammatory conditions that lead to pathology involving ILCs. Listed are examples of pathologies shown to involve ILCs, even though in most cases the causative role of ILCs, or their requirement in the pathology, remains to be established. Strong intestinal inflammatory pathology induced during IBD or by Salmonella enterica generates ILCs that produce both type 1 (IFNγ) and type 3 (IL-17) effector cytokines.

In contrast, the ILC2s field has benefited from RORα-deficient mice that lack ILC2s but not other types of lymphocytes, in particular Th2 cells (18, 105). RORα message is also expressed in ILC1s and ILC3s (106), but does not appear to be required for ILC3 development (105). RORα-deficient mice, termed staggerer mice, also develop an undersized cerebellum that translates into behavioural defects (107). Chimeric mice that lack RORα only in the hematopoietic compartment fail to develop acute lung pathology in response to papain, a protease allergen, demonstrating the role of ILC2s in priming the allergic response involving Th2 cells (89, 105). RORα-deficient mice were also used to show that ILC2s are required to expel the helminth Nyppostrongylus brasiliensis from the intestine (18) and to induce pulmonary fibrosis upon infection with Schistosoma mansoni through the production of IL-13 (108). The tools available to specifically ablate ILC2s recently expanded following the generation of mice that express the diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) on ILC2s but not on T cells, allowing for time-controlled ablation of ILC2s (86).

ILC2s and IL-13 are also associated with hepatic fibrosis induced in mice by thioacetamide, carbontetrachloride and Schistosoma mansoni (109), and with pulmonary fibrosis (108), chronic rhinosinusitis (110), and atopic dermatitis (111, 112), as well as allergen- (112, 113) and rhinovirus-induced asthma exacerbation in patients (114, 115). Finally, ILC2s are proposed to play a central role in asthma-induced obesity. ILC2s in VAT protect from obesity through the release of IL-5 and IL-13, and the recruitment of eosinophils (74). However, the accumulation of eosinophils into the asthmatic lungs may prevent their recruitment to VAT and thereby type 2 immunity from protecting the organism from high fat diet-induced obesity (116).

Targeting ILCs for prevention and therapy

As ILCs act promptly in response to infection and injury, and regulate type 1, type 2 and type 3 responses, they may be targeted to critically enhance or block immune responses early during vaccination, immunotherapy and inflammatory pathology. Towards this goal, it is imperative that the fundamental molecular signals that regulate ILC diversity and commitment are defined comprehensively. Although ILC-specific targets have not yet been identified, the activation pathways and effector molecules they share with T cells can be targeted early in the immune response. For example, inhibitors of RORγt have been identified primarily to block Th17-mediated inflammatory pathology, but these inhibitors can obviously be used to block ILC3s as well (117, 118). Similarly, RORα, a nuclear hormone receptor similar to RORγt, may be targeted to modulate ILC2s. Agonists for RORγt and RORα may also be developed to enhance the generation and activity of ILC3s and ILC2s, in order to enhance defence against mucosal pathogens or to modulate fat-induced metabolic diseases and allergy. A similar strategy may be followed to modulate the activity of NK cells and ILC1s by targeting T-bet.

The activity of ILC2s is promoted by the arachidonic acid metabolites leukotriene D4 (LTD4) and prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) through the cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 (CysLT1R) and the “chemoattractant receptor-homologous molecule expressed on Th2 cells” CRTH2 (76), respectively, but is impaired by the arachidonic metabolites lipoxin A4 (LXA4) and maresin-1 (119). Thus, an arsenal of lipid mediators, or inhibitors of these mediators (Montelukast, a leukotriene receptor antagonist), may be developed to control the activity of ILCs. The cytokines inducing the development and activity of specific subsets of ILCs, such as IL-12, IL-25 and IL-33, or IL-1β and IL-23 for ILC1s, ILC2s or ILC3s, respectively, as well as IL-2, may also be targeted, although the precise involvement of ILCs in specific diseases have not been determined within the multifarious effects that arise from blocking these pathways. For example, treatment of multiple sclerosis patients with Daclizumab, an antibody targeting the IL-2Rα (CD25), resulted in a decrease in the frequency of RORγt+ ILCs and an increase in the numbers of NK cells that correlated with drug efficacy (120). In addition, Ustekinumab, an antibody directed against the p40 subunit common to IL-12 and IL-23, shows high clinical efficacy against psoriasis (121). Furthermore, antibodies against IL-25 and IL-33 have shown efficacy in mouse models of allergic lung inflammation (122, 123), and intravenous anti-TSLP given prior to allergen challenge in mild asthmatic patients improves asthma symptoms (124). These cytokines can also be blocked by microbial compounds. For example, the excretory/secretory products of the helminth Heligmosomoides polygyrus impair the activity of ILC2s in response to airways challenges with extracts of the fungal allergen Alternaria alternata, presumably through suppression of the initial A. alternata-induced IL-33 production (125). Alternatively, microbial compounds may be used to boost one type of ILC in order to block the other types of ILCs. Finally, the effector cytokines produced by ILCs may be targeted with antibodies against IFNγ, IL-5 and IL13, or IL-17. For example, Mepolizumab (anti-IL-5) and Lebrikizumab (anti-IL-13) have shown encouraging results in clinical trials against asthma (126, 127).

Concluding Remarks

The multiple facets of ILC development, activation and function need to be further explored before efficient manipulation of ILCs can be achieved in the clinic. The developmental pathways leading to the different types of ILCs appear to be relatively complex, and modulation of these pathways by the microenvironment remains poorly understood, with questions remaining about ILC subset plasticity and stability. It will also be insightful to explore the development of ILCs not only during ontogeny, but also during evolution, in order to assess whether “cytotoxic” ILCs (NK cells) and “helper” ILCs (ILC1s, ILC2s and ILC3s) served as a blueprint for the appearance of CD8+ cytotoxic and CD4+ helper T cells.

Much remains to be uncovered on the activation and function of ILCs. We propose that ILCs promptly translate signals produced by infected or injured tissues into effector cytokines that activate and regulate local innate and adaptive effector functions. Signals produced by the tissues activating ILCs include cytokines, and possibly also stress ligands and microbial compounds. In terms of function, ILCs and T cells produce similar sets of effector cytokines; however the hallmark of ILCs is prompt and antigen-independent activation, placing them upstream as probable orchestrators of adaptive responses. Therefore, the cross-regulation of ILCs and T cells, involving DCs as a central platform of information exchange, needs to be deciphered using new mouse models that allow targeting each cell type individually. Furthermore, a role for ILCs beyond immunity, such as in the regulation of fat metabolism, needs to be unravelled in order to understand the integration of the immune system in host physiology.

Such accumulated knowledge should lead to new type of immunotherapies based on the manipulation of ILCs. As ILCs appear to play a major role in adjusting the developing immune response to the original insult, the manipulation of ILCs should allow the optimal shaping of immune responses in prevention and therapy. In the context of immunopathology, the manipulation of ILCs may allow blocking the development of detrimental types of immune responses.

Box 1.

Warning: the limits of nomenclature

The classification of ILCs into ILC1s, ILC2s and ILC3s reflects both the phenotypical and the functional characteristics of T helper cells, and serves to structure research into their phylogeny and functions. However, this classification also generates some debates as ILCs and T helper cells can co-express cytokines of more than one type. For example ILC3s and Th17 cells are found to co-express IFNγ and IL-17, characteristic of type 1 and type 3 responses respectively, during pathological inflammation (56, 103, 128). How should these cells be referred to? ILC3/1 cells or IFNγ-expressing ILC3s? Furthermore, ILC3s can evolve into ILC1s by downregulating the transcription factor RORγt and upregulating the transcription factor T-bet (103, 129). Therefore, it is possible that IFNγ-expressing ILC3s are in fact cells that transit from an ILC3 phenotype to an ILC1 phenotype, “so-called ex-ILC3s”. To further complicate an already opaque ILC world, a potential ILC2 precursor that is induced by IL-25 has been reported to have the capability to give rise to ILC3-like IL-17-producers, though in naïve mice or upon helminth infection they appear to default to a more conventional and less plastic ILC2 phenotype (43). Finally, fate mapping of PLZF+ ILC precursors shows that LTi cells develop along a pathway distinct from that of the other types of ILCs (17). In addition, LTi cells and NKp46+ ILC3s can be distinguished on the basis of their gene expression (106). This difference may have an evolutionary basis: as the programmed development of lymph nodes and Peyer’s patches is induced by LTi cells only in mammals (130), LTi cells may be a recent acquisition, whereas ILCs may have appeared with the advent of vertebrates or even before (49).

NK cells present another difficulty for classification. NK cells express T-bet and produce IFNγ, and thus are type 1 cells like Th1 cells. However, they also express Eomesodermin-dependent perforin and granzymes as do cytotoxic CD8+ T cells. It is therefore suggested that NK cells mirror CD8+ T cells while ILC1s mirror CD4+ Th1 cells (16, 131). Thus, NK cells may be termed “cytotoxic ILCs”. Distinguishing NK cells from ILC1s can be achieved by fate-mapping of Id2+ or PLZF+ precursor cells (16, 17), or using Eomesodermin reporter mice. However it is more difficult to discriminate these two ILC subsets using surface markers as they vary from tissue to tissue. For example, discriminating the two cell types is relatively straightforward in the liver, but more difficult in the spleen and small intestine (106). In the liver, ILC1s selectively express TRAIL and VLA1. In the spleen and small intestine, there are no distinctive surface markers identified, although the expression of CXCR6 on ILC1s and of the MHC class I receptors Ly49 and KIRs on NK cells can be partially informative. Finally, surface markers used to discriminate these cell types may vary depending on cellular activation.

Acknowledgments

G.E. is supported by grants from the Institut Pasteur, the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) and from the Pasteur-Weizmann Council. J.P.D. is supported by grants from the Institut Pasteur, Inserm, La Ligue National Contre le Cancer and the ANR. A.N.J.M. is supported by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and the Wellcome Trust.

References

- 1.Kiessling R, et al. Killer cells: a functional comparison between natural, immune T-cell and antibody-dependent in vitro systems. J Exp Med. 1976;143:772. doi: 10.1084/jem.143.4.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mebius RE, Rennert P, Weissman IL. Developing lymph nodes collect CD4+CD3−LTβ+ cells that can differentiate to APC, NK cells, and follicular cells but not T or B cells. Immunity. 1997;7:493. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80371-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adachi S, Yoshida H, Kataoka H, Nishikawa S. Three distinctive steps in Peyer’s patch formation of murine embryo. Int Immunol. 1997;9:507. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.4.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cella M, et al. A human natural killer cell subset provides an innate source of IL-22 for mucosal immunity. Nature. 2009;457:722. doi: 10.1038/nature07537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Satoh-Takayama N, et al. Microbial flora drives interleukin 22 production in intestinal NKp46+ cells that provide innate mucosal immune defense. Immunity. 2008;29:958. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luci C, et al. Influence of the transcription factor RORgammat on the development of NKp46+ cell populations in gut and skin. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:75. doi: 10.1038/ni.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanos SL, et al. RORgammat and commensal microflora are required for the differentiation of mucosal interleukin 22-producing NKp46+ cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:83. doi: 10.1038/ni.1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moro K, et al. Innate production of T(H)2 cytokines by adipose tissue-associated c-Kit(+)Sca-1(+) lymphoid cells. Nature. 2009;463:540. doi: 10.1038/nature08636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neill DR, et al. Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2 immunity. Nature. 2010;464:1367. doi: 10.1038/nature08900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernink JH, et al. Human type 1 innate lymphoid cells accumulate in inflamed mucosal tissues. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:221. doi: 10.1038/ni.2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuchs A, et al. Intraepithelial type 1 innate lymphoid cells are a unique subset of IL-12- and IL-15-responsive IFN-gamma-producing cells. Immunity. 2013;38:769. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spits H, Di Santo JP. The expanding family of innate lymphoid cells: regulators and effectors of immunity and tissue remodeling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:21. doi: 10.1038/ni.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qiu Y, et al. Eosinophils and type 2 cytokine signaling in macrophages orchestrate development of functional beige fat. Cell. 2014;157:1292. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee M, et al. Activated Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells Regulate Beige Fat Biogenesis. Cell. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brestoff JR, et al. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells promote beiging of white adipose tissue and limit obesity. Nature. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nature14115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klose CS, et al. Differentiation of type 1 ILCs from a common progenitor to all helper-like innate lymphoid cell lineages. Cell. 2014;157:340. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Constantinides MG, McDonald BD, Verhoef PA, Bendelac A. A committed precursor to innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 2014;508:397. doi: 10.1038/nature13047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong SH, et al. Transcription factor RORalpha is critical for nuocyte development. Nat Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.1038/ni.2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cherrier M, Sawa S, Eberl G. Notch, Id2 and RORγt sequentially orchestrate the fetal development of lymphoid tissue inducer cells. J Exp Med. 2012;209:277. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yokota Y, et al. Development of peripheral lymphoid organs and natural killer cells depends on the helix-loop-helix inhibitor Id2. Nature. 1999;397:702. doi: 10.1038/17812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seillet C, et al. Nfil3 is required for the development of all innate lymphoid cell subsets. J Exp Med. 2014;211:1733. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geiger TL, et al. Nfil3 is crucial for development of innate lymphoid cells and host protection against intestinal pathogens. J Exp Med. 2014;211:1723. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yagi R, et al. The transcription factor GATA3 is critical for the development of all IL-7Ralpha-expressing innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2014;40:378. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Serafini N, et al. Gata3 drives development of RORgammat+ group 3 innate lymphoid cells. J Exp Med. 2014;211:199. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boos MD, Yokota Y, Eberl G, Kee BL. Mature natural killer cell and lymphoid tissue-inducing cell development requires Id2-mediated suppression of E protein activity. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1119. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Male V, et al. The transcription factor E4bp4/Nfil3 controls commitment to the NK lineage and directly regulates Eomes and Id2 expression. J Exp Med. 2014;211:635. doi: 10.1084/jem.20132398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia-Ojeda ME, et al. GATA-3 promotes T-cell specification by repressing B-cell potential in pro-T cells in mice. Blood. 2013;121:1749. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-440065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakahiro T, Kurooka H, Mori K, Sano K, Yokota Y. Identification of BMP-responsive elements in the mouse Id2 gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;399:416. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.07.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang P, Zhao Y, Sun XH. Notch-regulated periphery B cell differentiation involves suppression of E protein function. J Immunol. 2013;191:726. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu X, et al. TH17 cell differentiation is regulated by the circadian clock. Science. 2013;342:727. doi: 10.1126/science.1243884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gascoyne DM, et al. The basic leucine zipper transcription factor E4BP4 is essential for natural killer cell development. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1118. doi: 10.1038/ni.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu W, et al. Nfil3 orchestrates the emergence of common helper innate lymphoid cell precursors. Cell Reports. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.057. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vosshenrich CA, et al. Roles for common cytokine receptor gamma-chain-dependent cytokines in the generation, differentiation, and maturation of NK cell precursors and peripheral NK cells in vivo. J Immunol. 2005;174:1213. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sawa S, et al. Lineage relationship analysis of RORγt+ innate lymphoid cells. Science. 2010;330:665. doi: 10.1126/science.1194597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crellin NK, Trifari S, Kaplan CD, Cupedo T, Spits H. Human NKp44+IL-22+ cells and LTi-like cells constitute a stable RORC+ lineage distinct from conventional natural killer cells. J Exp Med. 2010;207:281. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Possot C, et al. Notch signaling is necessary for adult, but not fetal, development of RORgammat(+) innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:949. doi: 10.1038/ni.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bando JK, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Identification and distribution of developing innate lymphoid cells in the fetal mouse intestine. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:153. doi: 10.1038/ni.3057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van de Pavert SA, et al. Chemokine CXCL13 is essential for lymph node initiation and is induced by retinoic acid and neuronal stimulation. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1193. doi: 10.1038/ni.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mucida D, et al. Reciprocal TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by retinoic acid. Science. 2007;317:256. doi: 10.1126/science.1145697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vicente-Suarez I, et al. Unique lamina propria stromal cells imprint the functional phenotype of mucosal dendritic cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8:141. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spencer SP, et al. Adaptation of innate lymphoid cells to a micronutrient deficiency promotes type 2 barrier immunity. Science. 2014;343:432. doi: 10.1126/science.1247606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van de Pavert SA, et al. Maternal retinoids control type 3 innate lymphoid cells and set the offspring immunity. Nature. 2014;508:123. doi: 10.1038/nature13158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang Y, et al. IL-25-responsive, lineage-negative KLRG1(hi) cells are multipotential ‘inflammatory’ type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:161. doi: 10.1038/ni.3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee JS, et al. AHR drives the development of gut ILC22 cells and postnatal lymphoid tissues via pathways dependent on and independent of Notch. Nat Immunol. 2011;13:144. doi: 10.1038/ni.2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qiu J, et al. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Regulates Gut Immunity through Modulation of Innate Lymphoid Cells. Immunity. 2011;36:92. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kiss EA, et al. Natural Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Ligands Control Organogenesis of Intestinal Lymphoid Follicles. Science. 2011;334:1561. doi: 10.1126/science.1214914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mielke LA, et al. TCF-1 controls ILC2 and NKp46+RORgammat+ innate lymphocyte differentiation and protection in intestinal inflammation. J Immunol. 2013;191:4383. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang Q, et al. T cell factor 1 is required for group 2 innate lymphoid cell generation. Immunity. 2013;38:694. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eberl G, Di Santo JP, Vivier E. The brave new world of innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol. 2014;16:1. doi: 10.1038/ni.3059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Unanue ER. Macrophages, NK cells and neutrophils in the cytokine loop of Listeria resistance. Research in immunology. 1996;147:499. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2494(97)85214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Dyken SJ, et al. Chitin activates parallel immune modules that direct distinct inflammatory responses via innate lymphoid type 2 and gammadelta T cells. Immunity. 2014;40:414. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Motomura Y, et al. Basophil-derived interleukin-4 controls the function of natural helper cells, a member of ILC2s, in lung inflammation. Immunity. 2014;40:758. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim BS, et al. Basophils promote innate lymphoid cell responses in inflamed skin. J Immunol. 2014;193:3717. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hughes T, et al. Interleukin-1beta selectively expands and sustains interleukin-22+ immature human natural killer cells in secondary lymphoid tissue. Immunity. 2010;32:803. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Coccia M, et al. IL-1beta mediates chronic intestinal inflammation by promoting the accumulation of IL-17A secreting innate lymphoid cells and CD4(+) Th17 cells. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1595. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Buonocore S, et al. Innate lymphoid cells drive interleukin-23-dependent innate intestinal pathology. Nature. 2010;464:1371. doi: 10.1038/nature08949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sawa S, et al. RORgammat(+) innate lymphoid cells regulate intestinal homeostasis by integrating negative signals from the symbiotic microbiota. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:320. doi: 10.1038/ni.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mortha A, et al. Microbiota-dependent crosstalk between macrophages and ILC3 promotes intestinal homeostasis. Science. 2014;343:1249288. doi: 10.1126/science.1249288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boehm U, Klamp T, Groot M, Howard JC. Cellular responses to interferon-gamma. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:749. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Songhet P, et al. Stromal IFN-gammaR-signaling modulates goblet cell function during Salmonella Typhimurium infection. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fallon PG, et al. IL-4 induces characteristic Th2 responses even in the combined absence of IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13. Immunity. 2002;17:7. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00332-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liang SC, et al. Interleukin (IL)-22 and IL-17 are coexpressed by Th17 cells and cooperatively enhance expression of antimicrobial peptides. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2271. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ye P, et al. Requirement of interleukin 17 receptor signaling for lung CXC chemokine and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor expression, neutrophil recruitment, and host defense. J Exp Med. 2001;194:519. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lanier LL. NK cell recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sun JC, Beilke JN, Lanier LL. Adaptive immune features of natural killer cells. Nature. 2009;457:557. doi: 10.1038/nature07665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Satoh-Takayama N, et al. The natural cytotoxicity receptor NKp46 is dispensable for IL-22-mediated innate intestinal immune defense against Citrobacter rodentium. J Immunol. 2009;183:6579. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Glatzer T, et al. RORgammat(+) innate lymphoid cells acquire a proinflammatory program upon engagement of the activating receptor NKp44. Immunity. 2013;38:1223. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Crellin NK, et al. Regulation of cytokine secretion in human CD127(+) LTi-like innate lymphoid cells by Toll-like receptor 2. Immunity. 2010;33:752. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bouskra D, et al. Lymphoid tissue genesis induced by commensals through NOD1 regulates intestinal homeostasis. Nature. 2008;456:507. doi: 10.1038/nature07450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kanamori Y, et al. Identification of novel lymphoid tissues in murine intestinal mucosa where clusters of c-kit+ IL-7R+ Thy1+ lympho-hemopoietic progenitors develop. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1449. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McDonald KG, et al. CC chemokine receptor 6 expression by B lymphocytes is essential for the development of isolated lymphoid follicles. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1229. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ansel KM, et al. A chemokine-driven positive feedback loop organizes lymphoid follicles. Nature. 2000;406:309. doi: 10.1038/35018581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Satoh-Takayama N, et al. The Chemokine Receptor CXCR6 Controls the Functional Topography of Interleukin-22 Producing Intestinal Innate Lymphoid Cells. Immunity. 2014;41:776. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Molofsky AB, et al. Innate lymphoid type 2 cells sustain visceral adipose tissue eosinophils and alternatively activated macrophages. J Exp Med. 2013;210:535. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nussbaum JC, et al. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells control eosinophil homeostasis. Nature. 2013;502:245. doi: 10.1038/nature12526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xue L, et al. Prostaglandin D2 activates group 2 innate lymphoid cells through chemoattractant receptor-homologous molecule expressed on TH2 cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1184. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.10.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Treiner E, et al. Selection of evolutionarily conserved mucosal-associated invariant T cells by MR1. Nature. 2003;422:164. doi: 10.1038/nature01433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bendelac A, Rivera MN, Park SH, Roark JH. Mouse CD1-specific NK1 T cells: development, specificity, and function. Annual Review of Immunology. 1997;15:535. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jensen KD, et al. Thymic selection determines gammadelta T cell effector fate: antigen-naive cells make interleukin-17 and antigen-experienced cells make interferon gamma. Immunity. 2008;29:90. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Martin B, Hirota K, Cua DJ, Stockinger B, Veldhoen M. Interleukin-17-producing gammadelta T cells selectively expand in response to pathogen products and environmental signals. Immunity. 2009;31:321. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sutton CE, et al. Interleukin-1 and IL-23 induce innate IL-17 production from gammadelta T cells, amplifying Th17 responses and autoimmunity. Immunity. 2009;31:331. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gasteiger G, Rudensky AY. Interactions between innate and adaptive lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:631. doi: 10.1038/nri3726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Eberl G, et al. An essential function for the nuclear receptor RORγt in the generation of fetal lymphoid tissue inducer cells. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:64. doi: 10.1038/ni1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hepworth MR, et al. Innate lymphoid cells regulate CD4+ T-cell responses to intestinal commensal bacteria. Nature. 2013;498:113. doi: 10.1038/nature12240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.von Burg N, et al. Activated group 3 innate lymphoid cells promote T-cell-mediated immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:12835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406908111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Oliphant CJ, et al. MHCII-mediated dialog between group 2 innate lymphoid cells and CD4(+) T cells potentiates type 2 immunity and promotes parasitic helminth expulsion. Immunity. 2014;41:283. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mirchandani AS, et al. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells drive CD4+ Th2 cell responses. J Immunol. 2014;192:2442. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jiao L, et al. NK cells promote type 1 T cell immunity through modulating the function of dendritic cells during intracellular bacterial infection. J Immunol. 2011;187:401. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Halim TY, et al. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells are critical for the initiation of adaptive T helper 2 cell-mediated allergic lung inflammation. Immunity. 2014;40:425. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tumanov AV, et al. Lymphotoxin controls the IL-22 protection pathway in gut innate lymphoid cells during mucosal pathogen challenge. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:44. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kruglov AA, et al. Nonredundant function of soluble LTalpha3 produced by innate lymphoid cells in intestinal homeostasis. Science. 2013;342:1243. doi: 10.1126/science.1243364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Monticelli LA, et al. Innate lymphoid cells promote lung-tissue homeostasis after infection with influenza virus. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1045. doi: 10.1031/ni.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Li J, et al. Biliary repair and carcinogenesis are mediated by IL-33-dependent cholangiocyte proliferation. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:3241. doi: 10.1172/JCI73742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Allen JE, Sutherland TE. Host protective roles of type 2 immunity: parasite killing and tissue repair, flip sides of the same coin. Semin Immunol. 2014;26:329. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Scandella E, et al. Restoration of lymphoid organ integrity through the interaction of lymphoid tissue-inducer cells with stroma of the T cell zone. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:667. doi: 10.1038/ni.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hanash AM, et al. Interleukin-22 protects intestinal stem cells from immune-mediated tissue damage and regulates sensitivity to graft versus host disease. Immunity. 2012;37:339. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dudakov JA, et al. Interleukin-22 drives endogenous thymic regeneration in mice. Science. 2012;336:91. doi: 10.1126/science.1218004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zenewicz LA, et al. Interleukin-22 but not interleukin-17 provides protection to hepatocytes during acute liver inflammation. Immunity. 2007;27:647. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zenewicz LA, et al. Innate and adaptive interleukin-22 protects mice from inflammatory bowel disease. Immunity. 2008;29:947. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kim HY, et al. Interleukin-17-producing innate lymphoid cells and the NLRP3 inflammasome facilitate obesity-associated airway hyperreactivity. Nat Med. 2014;20:54. doi: 10.1038/nm.3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cani PD, et al. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes. 2008;57:1470. doi: 10.2337/db07-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Burcelin R, Garidou L, Pomie C. Immuno-microbiota cross and talk: the new paradigm of metabolic diseases. Semin Immunol. 2012;24:67. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Klose CS, et al. A T-bet gradient controls the fate and function of CCR6-RORgammat+ innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 2013;494:261. doi: 10.1038/nature11813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sonnenberg GF, Monticelli LA, Elloso MM, Fouser LA, Artis D. CD4(+) Lymphoid Tissue-Inducer Cells Promote Innate Immunity in the Gut. Immunity. 2011;34:122. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Halim TY, et al. Retinoic-acid-receptor-related orphan nuclear receptor alpha is required for natural helper cell development and allergic inflammation. Immunity. 2012;37:463. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Robinette ML, et al. Transcriptional programs define molecular characteristics of innate lymphoid cell classes and subsets. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:306. doi: 10.1038/ni.3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hamilton BA, et al. Disruption of the nuclear hormone receptor RORα in staggerer mice. Nature. 1996;379:736. doi: 10.1038/379736a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hams E, et al. IL-25 and type 2 innate lymphoid cells induce pulmonary fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315854111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.McHedlidze T, et al. Interleukin-33-dependent innate lymphoid cells mediate hepatic fibrosis. Immunity. 2013;39:357. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mjosberg JM, et al. Human IL-25- and IL-33-responsive type 2 innate lymphoid cells are defined by expression of CRTH2 and CD161. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1055. doi: 10.1038/ni.2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kim BS, et al. TSLP elicits IL-33-independent innate lymphoid cell responses to promote skin inflammation. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:170ra16. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Salimi M, et al. A role for IL-25 and IL-33-driven type-2 innate lymphoid cells in atopic dermatitis. J Exp Med. 2013;210:2939. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Doherty TA, et al. Allergen challenge in allergic rhinitis rapidly induces increased peripheral blood type 2 innate lymphoid cells that express CD84. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1203. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.12.1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Beale J, et al. Rhinovirus-induced IL-25 in asthma exacerbation drives type 2 immunity and allergic pulmonary inflammation. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:256ra134. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hong JY, et al. Neonatal rhinovirus induces mucous metaplasia and airways hyperresponsiveness through IL-25 and type 2 innate lymphoid cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:429. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lloyd CM, Saglani S. Eosinophils in the spotlight: Finding the link between obesity and asthma. Nat Med. 2013;19:976. doi: 10.1038/nm.3296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Huh JR, et al. Digoxin and its derivatives suppress TH17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORgammat activity. Nature. 2011;472:486. doi: 10.1038/nature09978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Solt LA, et al. Suppression of TH17 differentiation and autoimmunity by a synthetic ROR ligand. Nature. 2011;472:491. doi: 10.1038/nature10075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Barnig C, et al. Lipoxin A4 regulates natural killer cell and type 2 innate lymphoid cell activation in asthma. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:174ra26. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Perry JS, et al. Inhibition of LTi cell development by CD25 blockade is associated with decreased intrathecal inflammation in multiple sclerosis. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:145ra106. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Bartlett BL, Tyring SK. Ustekinumab for chronic plaque psoriasis. Lancet. 2008;371:1639. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60702-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ballantyne SJ, et al. Blocking IL-25 prevents airway hyperresponsiveness in allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:1324. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Coyle AJ, et al. Crucial role of the interleukin 1 receptor family member T1/ST2 in T helper cell type 2-mediated lung mucosal immune responses. J Exp Med. 1999;190:895. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.7.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gauvreau GM, et al. Effects of an anti-TSLP antibody on allergen-induced asthmatic responses. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.McSorley HJ, Blair NF, Smith KA, McKenzie AN, Maizels RM. Blockade of IL-33 release and suppression of type 2 innate lymphoid cell responses by helminth secreted products in airway allergy. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:1068. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Corren J, et al. Lebrikizumab treatment in adults with asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1088. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Pavord ID, et al. Mepolizumab for severe eosinophilic asthma (DREAM): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:651. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60988-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Spits H, et al. Innate lymphoid cells–a proposal for uniform nomenclature. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:145. doi: 10.1038/nri3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Vonarbourg C, et al. Regulated expression of nuclear receptor RORgammat confers distinct functional fates to NK cell receptor-expressing RORgammat(+) innate lymphocytes. Immunity. 2010;33:736. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Eberl G. Inducible lymphoid tissues in the adult gut: recapitulation of a fetal developmental pathway? Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:413. doi: 10.1038/nri1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Diefenbach A, Colonna M, Koyasu S. Development, differentiation, and diversity of innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2014;41:354. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Magri G, et al. Innate lymphoid cells integrate stromal and immunological signals to enhance antibody production by splenic marginal zone B cells. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:354. doi: 10.1038/ni.2830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]