Abstract

While several studies indicate the importance of ephrin-B/EphB bidirectional signaling in excitatory neurons, potential roles for these molecules in inhibitory neurons are largely unknown. We identify here an autonomous receptor-like role for ephrin-B reverse signaling in the tangential migration of interneurons into the neocortex using ephrin-B (EfnB1/B2/B3) conditional triple mutant (TMlz) mice and a forebrain inhibitory neuron specific Cre driver. Inhibitory neuron deletion of the three EfnB genes leads to reduced interneuron migration, abnormal cortical excitability, and lethal audiogenic seziures. Truncated and intracellular point mutations confirm the importance of ephrin-B reverse signaling in interneuron migration and cortical excitability. A non-autonomous ligand-like role was also identified for ephrin-B2 that is expressed in neocortical radial glial cells and required for proper tangential migration of GAD65-positive interneurons. Our studies thus define both receptor-like and ligand-like roles for the ephrin-B molecules in controlling the migration of interneurons as they populate the neocortex and help establish excitatory/inhibitory (E/I) homeostasis.

Keywords: ephrin-B, EphB, bidirectional signaling, inhibitory interneuron migration, excitatory/inhibitory homeostasis

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Normal functioning of the cerebral cortex depends on the precise synaptic balance of excitatory neurons and inhibitory neurons, which together control the flow of information and synchronization of neural networks necessary for higher order brain activity. Proper excitatory/inhibitory (E/I) homeostasis is thus crucial for normal brain function and maintaining neuronal activity within a safe, normal range. Excitation is mediated principally by the neurotransmitter glutamate and pyramidal cells which are the projection neurons of the cortex, while inhibition is mediated by γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and interneurons which form local connections within the cortex. Growing evidence suggests interneuron dysfunction can affect the delicate balance between excitation and inhibition, leading to hyperexcitability and many psychiatric disorders including those associated with seizure activity such as epilepsy, autism spectrum disorders, fragile X syndrome, other intellectual disabilities, as well as schizophrenia, mood and anxiety disorders, sleep disorders, and drug addiction (Levy and Degnan, 2013; Lewis et al., 2005; Marin, 2012; Rossignol, 2011). While these conditions are distinct from each other, they typically have in common disruptions in the number/distribution/function of forebrain interneurons. This simplified view of psychiatric disorders is complicated by the fact that cortical interneurons constitute one of the most diverse groups of cells in the central nervous system as at least 20 different subtypes can be identified based on their morphological, electrophysiological, and neurochemical characteristics (Markram et al., 2004; Monyer and Markram, 2004).

To better understand how E/I balance is generated and maintained, it is crucial to study the origins and migration patterns of the excitatory and inhibitory neuron populations as the embryo develops as disruption of these early events likely affects homeostasis and may lead to psychiatric disorders. While glutamatergic excitatory neurons are born in the proliferative ventricular zone of the developing forebrain/telencephalon and migrate along radial glial cells in an inside-to-outside fashion to produce the well described laminated layered structure of the neocortex, GABAergic inhibitory interneurons originate from the preoptic area (POA) and ganglionic eminence (GE) bulges that form in the ventral aspect of the forebrain telencephalon (subpallium) and these cells migrate tangentially into the neocortex (Fig. 1A–B) (Batista-Brito and Fishell, 2009; Gelman and Marin, 2010; Marin, 2012; Rossignol, 2011). Although interneurons show a rich diversity in morphology, connectivity, electrophysiology, and expression of transcription factors, neuropeptides, and other molecular components, they can generally be subdivided early in development into two main groups based on expression of two isoforms of glutamic acid decarboxylase, GAD67 (Gad1) and GAD65 (Gad2). A number of molecular guidance systems have been suggested to play roles in the tangential migration of interneurons from their subpallial origins to their final neocortical destinations, including Semaphorin-Neuropilin, Slit-Robo, Neuregulin-ErbB, and Ephrin-Eph ligand-receptor systems (Andrews et al., 2008; Flames et al., 2004; Marin et al., 2001; Zimmer et al., 2011). However, our understanding of the mechanisms that control this unique form of neuron migration is rudimentary at best, especially compared to the vast literature centered on the radial migration of cortical excitatory neurons.

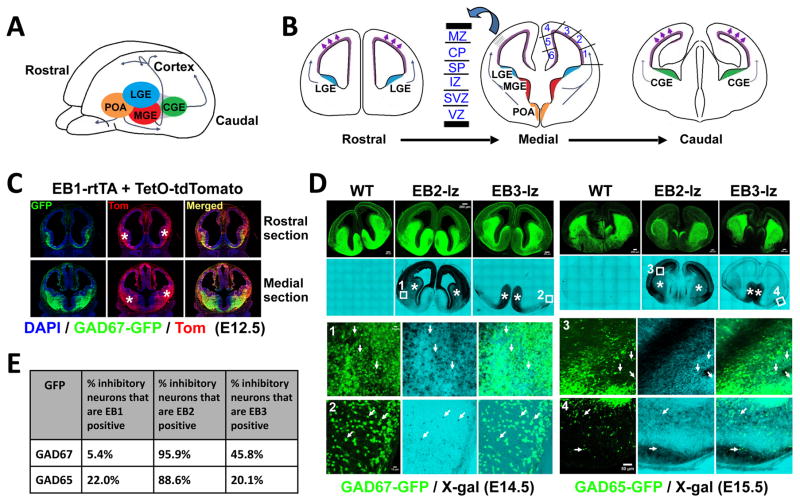

Fig. 1. Ephrin-B (EB) expression in inhibitory neurons in the developing forebrain.

(A) Interneurons originate from the ganglionic eminences (GE) and preoptic area (POA) and follow tangential migration pathways to populate the neocortex (thin arrows); lateral GE (LGE; blue color), medial GE (MGE; red color), and caudal GE (CGE; green color). (B) Schematics of coronal sections at embryonic age detailing the bins 1–6 used to quantify interneuron migration into defined neocortical regions. Excitatory neurons born in the VZ (indicated in purple color) migrate along radial glial cells to form defined cortical layers, the marginal zone (MZ), cortical plate (CP), subplate (SP), intermediate zone (IZ), subventricular zone (SVZ), and ventricular zone (VZ). Inhibitory neurons migrate into the neocortex (thin arrows) by interacting with the layered excitatory neurons and radial glia, forming layer-specific streams that extend into the developing cortex and hippocampus. (C) Ephrin-B1 (EB1) expression at E12.5 was visualized using a dox-inducible EB1-rtTA BAC transgene and a TetO-tdTomato indicator (Tom, red fluorescence) combined with a GAD67-GFP reporter (green fluorescence). EB1 is expressed in the the GEs (asterisks) and neocortex with clear overlap in GAD67-GFP positive inhibitory neurons in the ventral forebrain (yellow fluorescence in merged images). Dox-containing chow and drinking water was provided to timed-pregnant females 2 days prior to collection of embryos. No tdTomato red fluorescence was detected in the absence of dox treatment (not shown). (D) Ephrin-B2 (EB2) and ephrin-B3 (EB3) expression at E14.5 and E15.5 was detected using EB2lz and EB3lz mutations which express C-terminal truncated EB2-βgal and EB3-βgal fusion proteins that can be visualized using X-gal stain (black color in bright field) in combination with GAD67-GFP at E14.5 or GAD65-GFP at E15.5 (green fluorescence in confocal). EB2 is expressed in the GEs (asterisks), VZ, and neocortex (predominantly between the IZ and CP as well as outer MZ), while EB3 is strongly expressed in the ventral/medial forebrain (predominantly in the POA, indicated by asterisks) and the GEs. Numbered boxes indicate location of enlarged images with arrows identifing inhibitory neurons co-expressing EB2 or EB3 with GAD-GFP in the individual confocal (GFP fluorescence), bright-field (X-gal stain), and merged images. No X-gal stain was detected in sections from WT brains. (E) Quantification of EB1, EB2, and EB3 expressing cells in GAD67-GFP and GAD65-GFP inhibitory neurons obtained from short-term primary embryonic neuron cultures.

Here we identify important roles for the three highly conserved ephrin-B proteins (EB1, EB2, and EB3) in the tangential migration of inhibitory neurons into the neocortex. Ephrin-B’s are transmembrane molecules that interact with EphB receptor tyrosine kinases to propagate bidirectional signals into both the Eph-expressing cell and the ephrin-expressing cell (Cowan and Henkemeyer, 2002; Kullander and Klein, 2002). Our new data indicate the ephrin-B proteins function as cell autonomous receptors expressed on interneurons to transduce reverse signals to help guide their migration into the neocortex during embryonic development. Disruption of these reverse signals leads to reductions in inhibitory neuron populations within the developing and mature cortex and hippocampus, resulting in cortical hyperexcitability and lethal audiogenic seizures. We further show that EB2 can also act non-autonomously as a guidance cue expressed on radial glial cells to direct proper tangential migration of interneurons into the neocortex. Our study thus defines both receptor-like reverse signaling and ligand-like forward signaling roles for the ephrin-B proteins in the tangential migration of interneurons into the cortex and suggests bidirectional Ephrin-Eph signaling is crucial for normal establishment of E/I homeostasis in the brain.

Results

All three ephrin-Bs are expressed in inhibitory neurons

While the expression of ephrin-B and EphB molecules is well documented in excitatory neurons, there is scant information concerning their expression within inhibitory neurons. To address this, we utilized GAD65-GFP (Lopez-Bendito et al., 2004) and GAD67-GFP (Tamamaki et al., 2003) reporter mice which brightly label distinct GABAergic neuron populations with GFP as they are born in the subpallium and migrate tangentially into the neocortex. The two GAD-GFP reporters were each crossed with mice that either carried a doxycycline-inducible (dox) Tg-BAC-EfnB1rtTA transgene (EB1-rtTA) (Robichaux et al., 2014) and a TetO-tdTomato indicator (TRE-Bi-SG-T) (Li et al., 2010) to report EB1 expression, or to the EfnB2lz (EB2lz) (Dravis et al., 2004) and EfnB3lz (EB3lz) (Yokoyama et al., 2001) lacZ knockin mice that express intracellular truncated ephrin-B-βgal fusion proteins (EB2-βgal and EB3-βgal) that traffic normally to the plasma membrane and can be used to report either EB2 or EB3 expression, respectively. These EB1-rtTA, EB2lz, and EB3lz genetic tools are excellent reporters of the expression of the respective gene and exhibit exceptionally high sign-to-noise ratios, much higher than possible using traditional mRNA in situ hybridization or protein antibody approaches. The forebrains of embryos between 12.5 days development (E12.5) to birth (P0) containing these genetic reporters were then either collected and analyzed for co-expression of GAD-GFP and ephrin-B in coronal sections or the forebrain cells were disaggregated and subjected to short-term primary cultures for 2–3 days in vitro prior to being analyzed for co-expression (Fig. 1C–D, Fig. S1–3). This analysis revealed that all three ephrin-B’s are expressed in both GAD67-GFP and GAD65-GFP labeled inhibitory neurons, with expression of EB2 being detected in nearly all GFP labeled cells, followed by EB3 in ~20–46% of cells and EB1 in ~5–22% of cells (Fig. 1E, Fig. S1, S3). To confirm these results, we used fluorescent activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate single GAD67-GFP cells from the developing forebrain at P0 and subjected them to single-cell microarray analysis. Transcripts for all three EfnB genes were identified in the microarrays, again showing that more cells express EB2, followed by EB3, and then EB1 (Fig. S4). We also searched for Efnb and EphB expression in the Allen Institute for Brain Science database of single cell transcriptome patterns of >1,600 individual cells isolated from the mouse primary visual cortex, including 750 interneurons (http://casestudies.brain-map.org/celltax#section_explorea). Consistent with our analysis of embryonic expression patterns and single-cell microarray analysis at birth, the Allen Institute data also shows the Efnb genes are expressed in Gad2 (GAD65) and Gad1 (GAD67) interneurons, again with Efnb2 showing expression in 39–58% of the interneurons, followed by Efnb3 (23–44%), and then Efnb1 (4–12%) (Fig. S5). The transcriptome data further shows many interneurons co-express multiple Efnb genes in the same cell, and that EphB genes are also expressed in inhibitory neurons, especially EphB2 (Data File S1).

Inhibitory neuron deletion of ephrin-B leads to reduced interneurons in the neocortex

Given the above data demonstrating that all three ephrin-B’s are found within GAD67-GFP and GAD65-GFP labeled inhibitory neurons in the embryo, we next sought to determine the effect of deleting their expression selectively in this group of cells using conditional triple mutant (TMlz) mice. To generate TMlz mice, we combined loxP-flanked alleles in EfnB1 (EB1loxP) (Davy et al., 2004) and EfnB2 (EB2loxP) (Gerety and Anderson, 2002) with the EB3lz knockin (Yokoyama et al., 2001) as no conditional allele is available for this gene. While the EB3lz mutation expresses an intracellular truncated ephrin-B3-βgal fusion protein that retains ligand-like activity to bind EphB receptors (and EphA4) to stimulate forward signaling, it cannot transduce receptor-like reverse signals into the cells it is expressed on (Xu and Henkemeyer, 2009; Xu et al., 2011; Yokoyama et al., 2001). Further, like the EB2lz mutation (Cowan et al., 2004) (and see below), the EB3lz mutation is converted into the EB3T mutation by the action of Cre recombinase and this results in synthesis of an intracellular truncated EB3-T protein that does not have βgal protein attached, resulting in a protein that is trapped in the trans-Golgi network (TGN) and acts like a protein-null allele as it does not traffic to the plasma membrane. Summarizing, the TMlz line consists of EB1loxP;EB2loxP;EB3lz conditional alleles and either the GAD67-GFP or GAD65-GFP reporter. These mice appear normal, long-lived, and can be converted to triple null knockouts in select cells by the action of Cre recombinase. To delete ephrin-B expression selectively in forebrain inhibitory neurons, TMlz mice were combined with the Dlx1/2-Cre transgene (Potter et al., 2009) (I12b) and the Ai9 Rosa26-STOP-tdTomato Cre indicator strain (Madisen et al., 2010) used to monitor Cre activity. We first confirmed that Dlx1/2-Cre is active at the beginning stages of forebrain inhibitory neuron development as detected using Ai9 tdTomato (Tom) indicator fluorescence as early as E11.5 where it strongly labels cells in the ventral forebrain/subpallium that in progressive days labels more cells and produces interneurons that migrate laterally out of the GEs to stream tangentially into the neocortex (Fig. S6A). At E11.5 only a few Tom labeled interneurons are visible within the neocortex entering bin 1 and in progressive days they gradually increase in numbers and extend into additional bins primarily by streaming through the neocortical subventricular zone (SVZ) and marginal zone (MZ) to reach the most distal bins (5 and 6) by E14.5 and E15.5. The Dlx1/2-Cre driver and Tom indicator were also combined with GAD67-GFP and GAD65-GFP reporters to identify the optimum embryonic age for quantification of the two distinct migrating interneuron populations. At E13.5 essentially all Tom cells in the neocortex co-express GAD67-GFP (Fig. S6B), indicating that the migrating cells at age E13.5 are in fact GAD67-expressing interneuron populations. Very few GAD65-GFP cells are observed in the neocortex at age E13.5 (Fig. S6C), consistent with previous reports that this class of interneurons are born and start migrating at a somewhat later age. It was further determined that Dlx1/2-Cre activity is restricted to post-mitotic cells in the embryonic forebrain, so any phenotypes described in this analysis are likely not attributed to issues with cell proliferation (Fig. S6D). Finally, by analyzing sections from adult brains, it was determined that Dlx1/2-Cre is very restricted in its activity and deletes only in interneurons in the adult cortex and hippocampus (Fig. S6E–F). Given this information, all quantification of interneuron migration in Dlx1/2-Cre containing TMlz embryos (and Cre-negative TMlz control littermates and Cre-positive wild-type [WT] embryos collected at same age) was performed at age E14.5 for GAD67-GFP group and E15.5 for GAD65-GFP group.

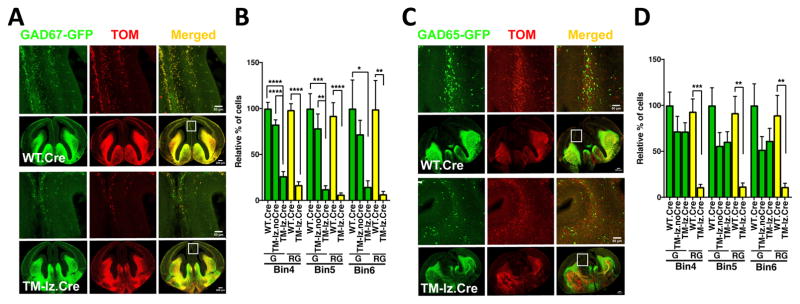

We found that the number of cells co-expressing Tom and GAD67-GFP in the neocortex from Dlx1/2-Cre containing TMlz embryos collected at E14.5 were strongly reduced relative to the Cre-positive WT controls in defined areas in bins 4–6 (Fig. 2A–B, yellow bars). As expected, similar results were obtained when just assessing GAD67-GFP labeled neurons, the Cre-positive TMlz embryos showed strong reductions in GFP labeled interneurons extending into bins 4–6 compared to the Cre-negative TMlz littermates and the Cre-positive WT controls (Fig. 2A–B, green bars). The number of cells co-expressing Tom and GAD65-GFP in the neocortex from Dlx1/2-Cre containing TMlz embryos collected at E15.5 were also found to be strongly reduced relative to the Cre-positive WT controls in defined areas in bin 4–6 (Fig. 2C–D, yellow bars). Curiously, in contrast to the observations with GAD67-GFP interneurons, when just assessing GAD65-GFP labeled interneurons, the Cre-positive TMlz embryos did not show strong reductions in labeled interneurons extending into bins 4–6 compared to the Cre-negative TMlz littermates, both groups exhibited a slight reduction compared to the Cre-positive WT controls (Fig. 2C–D, green bars). The most likely explanation for this observation is that for some unknown reason GAD65-GFP interneurons destined for the neocortex exhibit some ability to escape the Dlx1/2-Cre activity. Perhaps due to the very high population of GAD67-GFP and GAD65-GFP neurons that reside inside GEs region at age E14.5–15.5, many of which remain to produce the medium spiny inhibitory neurons of the striatum, there is some type of homeostatic mechanism at play that leads to GAD65-GFP positive cells that escape the Dlx1/2-Cre activity being able to populate the neocortex. Nevertheless, the strong reduction of GAD65-GFP/Tom double-positive cells in bins 4–6 of Dlx1/2-Cre containing TMlz embryos indicates loss of ephrin-B expression drastically affects this class of interneurons. To confirm the reduced interneuron populations associated with Dlx1/2-Cre mediated deletion of the three ephrin-B’s, the EB3lz allele was replaced with a protein-null allele, generating an EB1loxP;EB2loxP;EB3− triple mutant (TM) mouse. Like the TMlz animals, the Dlx1/2-Cre containing TM embryos exhibited striking reductions in GAD67-GFP and GAD65-GFP interneurons within the neocortex (Fig. S7A–B). Importantly, the number of GAD-GFP interneurons populating the neocortex in both TMlz and TM embryos in the absence of Dlx1/2-Cre appeared for the most part fairly normal when compared to the WT controls, indicating loss of EB3 protein alone had little, if any, effect. Together, these data indicate that inhibitory neuron specific deletion of ephrin-B expression leads to, highly significant reductions in the number of interneurons populating the neocortex.

Fig. 2. Conditional deletion of ephrin-B in TMlz triple mutants using an inhibitory neuron specific Dlx1/2-Cre driver leads to reduced populations of interneurons in the embryonic neocortex.

(A) Representative confocal images of GAD67-GFP labeled interneurons in the neocortex at age E14.5 in Dlx1/2-Cre containing wild-type (WT.Cre) and TMlz (TM-lz.Cre) brains. The boxed regions in the low magnification images indicate location of the high magnification images, with isolated GAD67-GFP reporter (green fluorescence), Rosa26-STOP-tdTomato indicator (Tom, red fluorescence), and merged signals to identify those cells co-labeled with GFP and Tom (yellow). (B) Quantification of the number of GAD67-GFP interneurons in the neocortex at E14.5 within bins 4–6 of coronal sections from Dlx1/2-Cre-positive TMlz animals (TM-lz.Cre) compared to Cre-negative TMlz (TM-lz.noCre) littermates and Cre-positive WT animals (WT.Cre). Total GAD67-GFP-positive cells (G) and number of green cells that were also exposed to Cre (red+green cells, RG) were counted and proportionally compared to the WT.Cre brains. N values for embryonic brain hemispheres: WT.Cre (6), TM-lz.noCre (8), and TM-lz.Cre (8); mean ± s.e.m.; one-way ANOVA (post-hoc Tukey test); * P< 0.05, ** P< 0.01, *** P<0.001, **** P<0.0001. (C) Representative confocal images of GAD65-GFP labeled interneurons in the neocortex at age E15.5 in Dlx1/2-Cre containing WT and TM-lz brains. The boxed regions in the low magnification images indicate location of the high magnification images, with GAD65-GFP reporter (green), Tom indicator (red), and merged signals (yellow). (D) Quantification of the number of GAD65-GFP interneurons in the neocortex at E15.5 within bins 4–6 of coronal sections from TM-lz.Cre animals compared to TM-lz.noCre littermates and WT.Cre animals. Total GAD65-GFP-positive cells (G) and number of green cells that were also exposed to Cre (red+green cells, RG) were counted and proportionally compared to the WT.Cre brains. N values for embryonic brain hemispheres: WT.Cre (8), TM-lz.noCre (6), and TM-lz.Cre (6); mean ± s.e.m.; one-way ANOVA (post-hoc Tukey test); * P< 0.05, ** P< 0.01, *** P<0.001, **** P<0.0001.

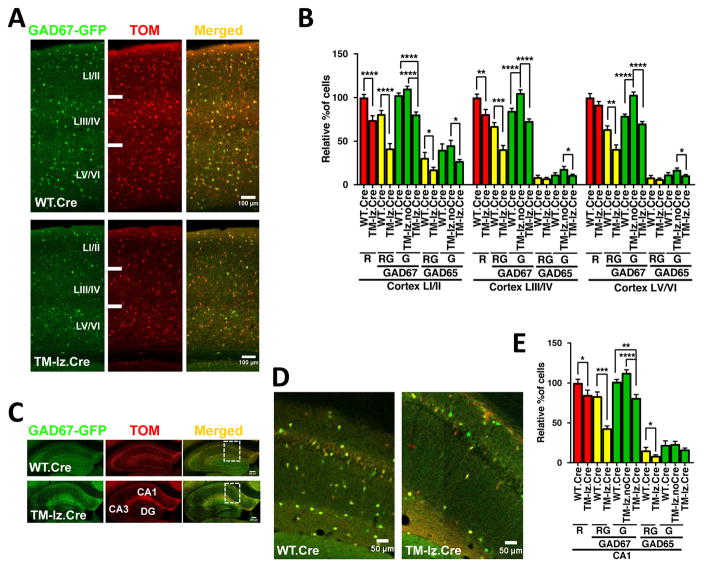

Ephrin-B deletion reduces interneuron populations in the adult brain

To determine if the reduced number of interneurons in the embryo is reflected by a loss of interneurons in the mature brain, populations of Dlx1/2-Cre deleted (Tom-positive) GAD67-GFP and GAD65-GFP (GFP-positive) interneurons were analyzed in the somatosensory cortex and hippocampus of TMlz adult mice (Fig. 3). The data shows the numbers of Tom/GFP double-positive interneurons were significantly decreased in the cortex and in the CA1 region of the hippocampus (Fig. 3B, E, yellow bars), but not in the dentate gyrus (DG) or CA3 areas (data not shown). For the GAD67-GFP interneurons, reductions were observed in all layers of the cortex, whereas for GAD65-GFP reduction was in layers I/II, which is the region where most of this subtype normally populate. Reduced Tom/GFP double-positive interneurons were also observed in analysis of Dlx1/2-Cre containing TM adult brains (Fig. S7C–D).

Fig. 3. Conditional deletion of ephrin-B in TMlz triple mutants using an inhibitory neuron specific Dlx1/2-Cre driver results in reduced populations of interneurons in the cortex and CA1 hippocampal region of the adult brain.

(A) Representative confocal images of GAD67-GFP (green) and Dlx1/2-Cre exposed (red) interneurons in WT.Cre and TM-lz.Cre adult mice (>P90) in coronal sections of the cortex. The merged images show that most all GAD67-GFP labeled interneurons were exposed to Cre (yellow). (B) Quantification of the Dlx1/2-Cre exposed interneurons (red, R), GAD67-GFP or GAD65-GFP expressing interneurons (green, G), and of Cre-exposed cells that also express the corresponding GFP reporter (red+green cells, RG) was determined by counting cells in defined cortex layers I/II, III/IV, V/VI from WT.Cre, TM-lz.noCre, and TM-lz.Cre brains. (C) Representative confocal images of GAD67-GFP (green) and Dlx1/2-Cre exposed (red) interneurons in WT.Cre and TM-lz.Cre adult mice (>P90) in coronal sections of the hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG), CA3, and CA1 regions. (D) High magnification merged images of the CA1 region boxed in C showing reduced numbers of interneurons in TM-lz.Cre brains. (E) Quantification of reduced GAD67-GFP and GAD65-GFP interneuron populations in Dlx1/2-Cre exposed brains in CA1 region of the hippocampus. N values for GAD67-GFP adult brain hemispheres are: WT.Cre (18), TM-lz.noCre (16), and TM-lz.Cre (6); for GAD65-GFP: WT.Cre (10), TM-lz.noCre (8), and TM-lz.Cre (16); mean ± s.e.m.; one-way ANOVA (post-hoc Tukey test); * P< 0.05, ** P< 0.01, *** P<0.001, **** P<0.0001.

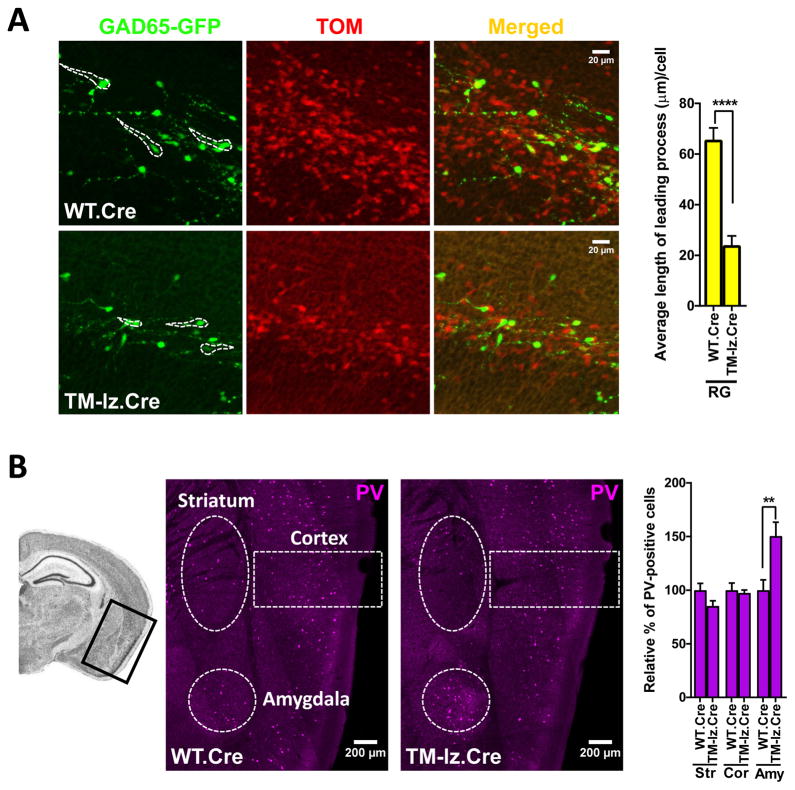

Ephrin-B deletion affects length of the leading cell process in migrating cortical interneurons

To gain a better understanding for why the numbers of interneurons are reduced in the embryonic neocortex and adult cortex/hippocampus of Dlx1/2-Cre containing TMlz brains, we first assessed whether the absolute number of inhibitory neurons is altered in the embryonic forebrain following deletion of ephrin-B expression. To do this, FACS of live cells from disaggregated E14.5 forebrains was used to count the number of Dlx1/2-Cre exposed (indicated by Ai9 driven Tom expression) and GAD65-GFP inhibitory neurons in WT and TMlz animals. The FACS data indicated Dlx1/2-Cre deletion of ephrin-B expression did not affect the number of Tom+ or GFP+ inhibitory neurons in the embryonic forebrain (Fig. S8). We then utilized GAD65-GFP to assess the length of the leading cellular process in labeled Dlx1/2-Cre exposed interneurons as the GFP fluorescence of this reporter provides good visualization of this extension. We found that the leading process of labeled cells within bins 2–3 at E15.5 was greatly reduced on average from 65.71 ± 4.61 μm in WT.Cre to 24 ± 3.66 μm in TMlz.Cre (Fig. 4A). This result indicates that loss of ephrin-B expression may affect the ability of interneurons to extend cell processes involved in tangential migration as they traverse the developing neocortex. If interneuron migration is indeed reduced/retarded in the embryonic brain, then it is possible these cells may accumulate in more lateral regions of the cortex (i.e. bin 1) or in the striatum. To assess this possibility, parvalbumin (PV) immunoreactive interneurons were counted in the lateral striatum and in lateral cortical areas of the amygdala and entorhinal/perirhinal cortex in adult brains. The data indicate that approximately 50% more PV+ cells are present in the amygdala of TMlz.Cre compared to WT.Cre (Fig. 4B). Combined, the above results indicate that Dlx1/2-Cre mediated deletion of ephrin-B does not affect absolute number of inhibitory neurons produced, but it does affect the leading cell process of migrating interneurons and this is associated with the accumulation of cells in the lateral region of the mature cortex.

Fig. 4. Inhibitory neuron deletion of ephrin-B affects the length of the leading process in migrating interneurons and results in accumulation of interneurons in lateral regions of the cortex.

(A) The length of the leading cell process of Dlx1/2-Cre-exposed GAD65-GFP cells (red+green, RG) was determined in bins 2–3 of coronal sections from WT.Cre and TM-lz.Cre embryos collected at E15.5. Shown are representative confocal images with identified RG cells outlined in white dashed lines and bar graph shows quantification of the data. N values for embryonic brain hemispheres are: WT.Cre (8 brains – 435 cells analyzed) and TM-lz.Cre (6 brains – 114 cells analyzed). (B) PV-positive cells were counted in lateral regions of the cortex and striatum from coronal sections of adult brains. Dash lines represent areas that were counted in the striatum (Str, 0.4 mm2), entorhinal/perirhinal cortex (Cor, 0.5 mm2), and amygdala (Amy, 0.2 mm2). N values for adult brain hemispheres are: WT.Cre (12) and TM-lz.Cre. (8); mean ± s.e.m.; t-test, two-tail ed; ** P< 0.01, **** P<0.0001.

Inhibitory neuron deletion of ephrin-B leads to cortical hyperexcitability and lethal seizures

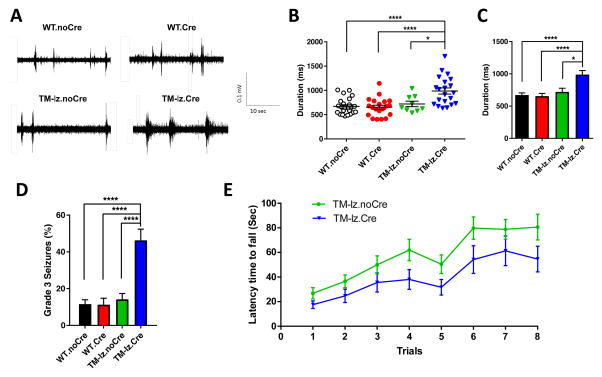

We next used electrophysiological recordings to examine UP states in the somatosensory cortex to determine if inhibitory neuron ephrin-B deletion leads to alterations in cortical circuit activity and E/I homeostasis. UP states measure spontaneously occurring activity states in the neocortex, which occur in vivo during waking states and rhythmically during slow wave sleep (Haider and McCormick, 2009; Sanchez-Vives and McCormick, 2000). UP states identify depolarized firing states of neurons that are driven by local recurrent excitation and inhibition, and occur synchronously among all neurons in a cortical region. Such recordings have been used in the Fragile X syndrome (FXS) mouse model of inherited intellectual disability to identify cellular and synaptic defects that result in increased excitation of cortical networks under baseline conditions as evident by UP states that are longer in duration in Fmr1 knockout mice (Gibson et al., 2008; Hays et al., 2011). We measured spontaneously generated UP states in live slices of Dlx1/2-Cre containing TMlz brains within layer IV of the primary somatosensory cortex, which revealed a highly significant increase in the duration of UP states relative to Cre-negative TMlz littermates and WT controls (Fig. 5A–C). The amplitude and frequency of UP states were not significantly different between the Dlx1/2-Cre containing TMlz and WT controls, though the Cre-negative TMlz brains exhibited a reduced amplitude compared to the Cre-positive TMlz mice (Fig. S9A–B). The data indicates the neocortex of Dlx1/2-Cre containing TMlz mice are hyperexcitable as they exhibit a longer duration of spontaneous UP states similar to Fmr1 mice.

Fig. 5. Inhibitory neuron deletion of ephrin-B leads to longer duration cortical UP states, lethal audiogenic seizures, and poor motor coordination.

(A–C) Electrophysiological recordings of brain slices obtained at P20–24 were used to assess the spontaneous intrinsic activity of cortical neural networks in layer IV of the somatosensory cortex. Shown are representative traces of UP state duration for each genotype (A), a scatter plot of the data (B), and bar graph summary (C). N values: WT.noCre (6 brains – 24 slices), WT.Cre (6 brains – 20 slices), TM-lz.noCre (2 brains – 9 slices), and TM-lz.Cre (5 brains – 21 slices); mean ± s.e.m.; one-way ANOVA (post-hoc Tukey test); * P< 0.05, **** P<0.0001. (D) Animals were assessed for susceptibility to audiogenic seizures at age P20–24 by exposing to a loud sound (110 dB) for 3.5 minutes and scoring for abnormal seizure-related phenotypes on the following scale: 0 = no response; 1 = wild running; 2 = tonic-clonic seizures; 3 = status epilepticus and death. N values: WT.noCre (190), WT.Cre (80), TM-lz.noCre (120), and TM-lz.Cre (67); mean ± s.e.m.; Fisher’s exact test; **** P<0.0001. (E) Dlx1/2-Cre-positive TM-lz mice exhibited a trend towards decreased rotarod performance compared to control Cre-negative TM-lz littermates, although the differences did not reach a level of significance. Adult mice were assessed at age >P90. N values: TM-lz.noCre (24) and TM-lz.Cre (20); mean ± s.e.m.; t-test, two-tailed.

To determine if the Dlx1/2-Cre containing TMlz mice exhibit abnormal behavior, we subjected them to a loud (>110 dB) sound to determine if they were susceptible to audiogenic seizures. Such tests have been used to assess hyperexcitable behavior in other mouse models such as Fmr1 and Homer knockouts (Chen and Toth, 2001; Dolen et al., 2007; Ronesi et al., 2012) and may implicate involvement of GABA and cortical auditory networks (Faingold, 2002; Rotschafer and Razak, 2013). Dlx1/2-Cre containing TMlz mice exhibited a highly significant increase in lethal audiogenic seizures relative to Cre-negative TMlz littermates and WT controls (Fig. 5D). Dlx1/2-Cre containing TMlz mice were also subjected to other behavioural tests for motor coordination and locomotion. Here they appeared fairly normal and exhibited a non-significant trend towards falling earlier on the rotarod test (Fig. 5E) and normal activity in locomotor and beam crossing activities (Fig. S9C–D). The data indicate inhibitory neuron deletion of ephrin-B expression does not affect motor coordination or locomotor behaviours, though it does result in a striking increase in sound-induced seizure activity.

Intracellular mutations in ephrin-B lead to reduced interneuron populations in the neocortex

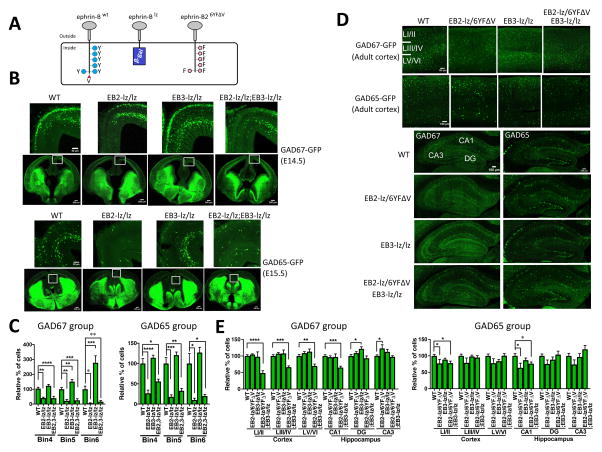

The above data indicate inhibitory neuron expressed ephrin-B proteins function in the migration of interneurons into the neocortex and have roles in regulation of cortical excitability, E/I homeostasis, and seizure activity. To confirm the idea that ephrin-B proteins have cell autonomous reverse signaling roles in inhibitory neurons, we combined GAD67-GFP and GAD65-GFP reporters with EB2lz and EB3lz intracellular truncation mutants which express intracellular truncated EB2-βgal and EB3-βgal fusion proteins that lack the respective intracellular domain and are thought to block most all forms of reverse signaling (Fig. 6A). Analysis of EB2lz/lz single mutants and EB2lz/lz;EB3lz/lz double mutants showed the number of GAD67-GFP and GAD65-GFP interneurons populating into the neocortex during E14.5-E15.5 was significantly reduced in these embryos compared to WT and EB3lz/lz single mutant littermates (Fig. 6B–C). To determine if the reduced number of labeled cells is simply due to an increase in apoptosis, EB2lz/lz single mutants and EB2lz/lz;EB3lz/lz double mutants were assayed with active/cleaved caspase 3 antibodies to detect dying cells. No increase in cell death was observed compared to WT controls or EB3lz/lz single mutants (Fig. S10). Combined, these data suggest that reverse signaling, particularly that mediated by ephrin-B2, contributes to the migration of interneurons during embryonic development.

Fig. 6. Intracellular ephrin-B truncation and point mutations disrupt interneuron migration and population into the cortex and hippocampus.

(A) Schematic diagrams of EBwt (WT), EBlz (EB-lz), and EB26YFΔV (EB2-6YFΔV) mutations used in the analysis. (B) Representative high and low magnification confocal images of embryonic brains containing GAD67-GFP at E14.5 (upper panels) or GAD65-GFP at E15.5 (lower panels) visualizing interneurons from WT, EB2-lz/lz single mutant, EB3-lz/lz single mutant, and EB2-lz/lz;EB3-lz/lz double mutant. (C) Quantification of GAD67-GFP cells from E14.5 embryos (left side) and GAD65-GFP cells from E15.5 embryos (right side) populating bins 4, 5, and 6. N values for GAD67 embryonic brain hemispheres: WT (26), EB2-lz/lz (6), EB3-lz/lz (24), EB2-lz/lz;EB3-lz/z (14); and for GAD65: WT (22), EB2-lz/lz (6), EB3-lz/lz (20), and EB2-lz/lz;EB3-lz/lz (10); mean ± s.e.m.; one-way ANOVA (post-hoc Tukey test); * P< 0.05, ** P< 0.01, *** P<0.001, **** P<0.0001; or t-test (two-tailed, unpaired) * P< 0.05. (D) Representative confocal images of adult cortex (upper panels) and hippocampus (lower panels) of WT, EB2-lz/6YFΔV single mutants, EB3-lz/lz single mutants, and EB2-lz/6YFΔV;EB3-lz/lz double mutants in GAD67-GFP and GAD65-GFP cell populations. (E) Quantification of interneuron cell populations. N values for GAD67 adult brain hemispheres are: WT (18), EB2-lz/6YFΔV (8), EB3-lz/lz (8), and EB2-lz/6YFΔV;EB3-lz/lz (6); and for GAD65: WT (24), EB2-lz/6YFΔV (8), EB3-lz/lz (14) and EB2-lz/6YFΔV;EB3-lz/lz (10); mean ± s.e.m.; one-way ANOVA (post-hoc Tukey test); * P< 0.05, ** P< 0.01, *** P<0.001, **** P<0.0001; or t-test (two-tailed, unpaired) * P< 0.05.

While EB2lz/lz mutants survive embryonic development and are born alive, these animals die on the first day of birth due to various developmental abnormalities (Bennett et al., 2013; Cowan et al., 2004; Dravis et al., 2004; Dravis and Henkemeyer, 2011) and thus preclude an analysis of interneuron populations in the adult brain. We therefore employed a point mutation in this gene, ephrin-B26YFΔV (EB26YFΔV) (Thakar et al., 2011) which expresses a full-length EB2 protein whose intracellular domain cannot become tyrosine phosphorylated to allow docking to the SH2 domain adaptor protein Grb4/Nckβ/Nck2 and cannot be bound by PDZ domain proteins at the C-terminal tail, which are two major avenues of reverse signaling (Fig. 6A). Previous studies have demonstrated that the EB2lz/6YFΔV allele combination results in animals that live to adulthood (Bennett et al., 2013; Dravis and Henkemeyer, 2011) and so we analyzed the GAD67-GFP and GAD65-GFP interneuron populations in mature brains using this allele combination. For GAD67-GFP interneurons we found that while the EB2lz/6YFΔV single mutants exhibited fairly normal populations, the EB2lz/6YFΔV;EB3lz/lz double mutants showed a highly significant reduction of interneurons populations in all layers of the cortex as well as in CA1 region of the hippocampus (Fig. 6D–E), mirroring the results observed with Dlx1/2-Cre containing TMlz adults. This indicates that reverse signaling mediated by EB2 and EB3 work as a team to control the adult populations of this class of interneurons. Interestingly, analysis of GAD65-GFP interneurons revealed that both EB2lz/6YFΔV single mutants and EB2lz/6YFΔV;EB3lz/lz double mutants exhibited reductions in layer I/II of cortex and CA1 of hippocampus (Fig. 6D–E), indicating that EB2 is involved in regulating the adult populations of these interneuons.

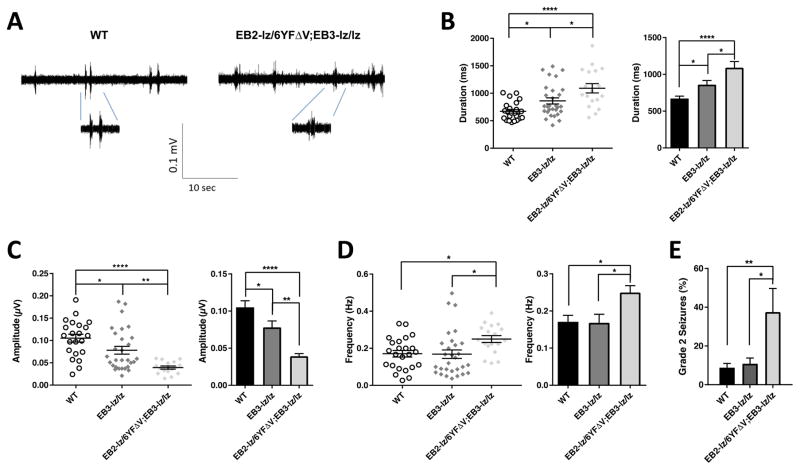

As EB2lz/6YFΔV; EB3lz/lz double mutants can be recovered as viable adult mice, their brains were also assayed for cortical excitability in vitro by measuring UP state duration, amplitude, and frequency. The results revealed a highly significant increase in duration of UP states in the EB2lz/6YF;EB3lz/lz double mutant mice relative to WT controls (Fig. 7A–B) and similar to what was observed in the Dlx1/2-Cre containing TMlz conditionals. Interestingly, in contrast to the Cre-positive TMlz mice, the double mutants also exhibited a significant decrease in UP state amplitude (Fig. 7C) and increase in UP state frequency (Fig. 7D). Furthermore, while the EB2lz/6YF;EB3lz/lz double mutant mice did not exhibit an increase in lethal seizures following exposure to loud sounds, they did show a significant increase in non-lethal grade 2 tonic-clonic seizures (Fig. 7E). Combined, these data indicate that EB2lz/6YFΔV single mutants and especially EB2lz/6YFΔV; EB3lz/lz double mutants exhibit reduced interneuron migration into the neocortex, with effects on cortical excitability and seizure activity in the adult. However, there are differences compared to the inhibitory neuron specific deletion in the Dlx1/2-Cre containing TMlz mutants, which likely reflects the fact that the EB26YFΔV, EB2lz, EB3lz alleles assayed here are germline mutations and thus may have effects because of expression of these mutant proteins in other cell types in addition to inhibitory neurons (see below).

Fig. 7. Intracellular ephrin-B truncation and point mutations leads to altered cortical UP states and increased non-lethal audiogenic seizures.

(A–D) Electrophysiological recordings of brain slices obtained at P20–24 were used to assess the spontaneous intrinsic activity of cortical neural networks in layer IV of the somatosensory cortex. Shown are representative traces of UP states for indicated genotypes (A) and scatter plots of the data and bar graph summaries of the UP state duration (B), amplitude (C), and frequency (D). N values: WT (6 brains – 24 slices), EB3-lz/lz single mutant (4 brains – 29 slices), and EB2-lz/6YFΔV;EB3-lz/lz double mutant (2 brains – 18 slices); mean ± s.e.m.; one-way ANOVA (post-hoc Tukey test); * P< 0.05, ** P< 0.01, *** P< 0.001, **** P<0.0001. (E) EB2-lz/6YFΔV;EB3-lz/lz double mutant mice assessed at age P20–24 exhibited a significant increase in grade 2 audiogenic seizures compared to control EB3-lz/lz single mutant littermates and WT mice. N values: WT (160), EB3-lz/lz (111), and EB2-lz/6YFΔV;EB3-lz/lz (16); mean ± s.e.m.; Fisher’s exact test; * P< 0.05, ** P< 0.01, **** P<0.0001.

Ephrin-B2 also exhibits a non-autonomous role in interneuron migration

The data using Dlx1/2-Cre to delete ephrin-B expression in TMlz and TM animals demonstrates the ephrin-B molecules have important cell autonomous functions within interneurons to control their migration and population into the neocortex. Consistent with this idea, the analysis of EB2lz/lz single mutant and EB2lz/lz;EB3lz/lz double mutant embryos with the GAD-GFP reporters also indicate that mutations which delete the intracellular domain of ephrin-B2 implicated in reverse signaling have profound effects on interneuron migration into the neocortex. On the other hand, in contrast to those results, analysis of EB26YFΔV/6YFΔV single mutant and EB26YFΔV/6YFΔV;EB3lz/lz double mutant embryos indicated a normal population of GAD65-GFP labeled interneurons in the neocortex and only a mild reduction in the GAD67-GFP group (Fig. S11). This might indicate the ephrin-B2 cell autonomous role involves components of reverse signaling that are not disrupted by the loss of SH2 or PDZ domain binding to its C-terminal intracellular tail. However, we recently published a study that showed in lymphatic valve development the EB2lz-encoded EB2-βgal fusion protein can act as a dominant overactive ‘super-ligand’ to promote excessive EphB4 forward signaling, presumably due to the formation of super-aggregates of βgal tetramers (Zhang et al., 2015). That study also showed the EB26YFΔV-encoded EB2-6YFΔV protein acts as a weaker ligand than EB2-WT, perhaps due to the inability of this molecule to be bound by PDZ domain proteins which likely aid in the clustering and presentation of the WT protein important for ligand-like activity (and we believe the reason EB2lz/6YFΔV mice can survive to adulthood is that the combination of one ‘super-ligand’ allele and one ‘weak-ligand’ allele balances each other out to provide relatively normal levels of EB2 ligand activity and forward signaling). We note that EB2 in particular is expressed to very high levels in cells of the neocortex that are not interneurons (Fig. 1D, Fig. S2), being most intense within two strips in the inner VZ and outer MZ of the neocortex, and in a wide strip in the middle IZ/CP layers. We further note that the majority of GAD67-GFP and GAD65-GFP expressing interneurons in the neocortical migratory paths appear to avoid these localized regions of EB2 expression, and instead stream through the two lines in SVZ and lower MZ that do not express high levels of this molecule.

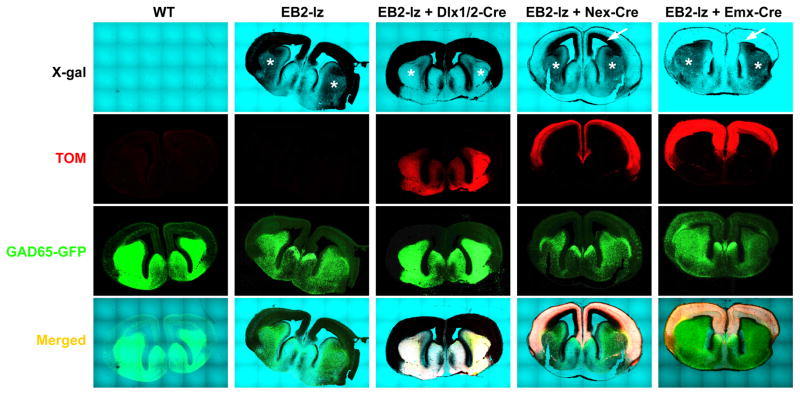

To explore the possibility that EB2lz-encoded EB2-βgal fusion protein can act as a dominant overactive ‘super-ligand’ to promote excessive forward signaling that constrains/impedes migration of interneurons into the neocortex, we took advantage of the ability to convert using Cre recombinase the EB2lz allele into the EB2T allele which expresses a TGN-trapped protein that is unable to function as a ligand (Cowan et al., 2004). To test this idea, GAD65-GFP interneurons were examined in EB2lz/lz mutant embryos that contained either the Dlx1/2-Cre driver (inhibitory neurons), Nex-Cre driver (Goebbels et al., 2006)(excitatory neurons), or the Emx1-Cre driver (Iwasato et al., 2000) (excitatory neurons and radial glial cells) with the Ai9 Tom indicator. X-gal stains were used to monitor expression of the EB2-βgal fusion protein to verify that Dlx1/2-Cre deleted expression in the inhibitory neuron population in the GEs, Nex-Cre deleted expression in the outer layers of neocortex, and Emx1-Cre deleted all expression in the neocortex (Fig. 8). As expected in crosses with the three different Cre drivers, the number of GAD65-GFP cells were significantly decreased in bins 4–6 in Cre-negative EB2lz/lz embryos compared to their Cre-positive EB2+/+ WT control littermates (Fig. 9, upper images). However, while the number of GAD65-GFP interneurons entering bins 4–6 cells in Dlx1/2-Cre or Nex-Cre containing EB2lz/lz embryos remained unchanged from the Cre-negative EB2lz/lz controls, complete rescue in the migration of GAD65-GFP interneurons was observed in the EB2lz/lz embryos that contained the Emx1-Cre driver (Fig. 9, lower images). The data was highly significant and the level of migration into bins 4–6 appeared indistinguishable from the Emx1-Cre containing EB2+/+ WT control littermates (Fig. 9, bar graphs). This result indicates that removal of the EB2-βgal super-ligand activity within radial glial cells alone or in combination with excitatory neurons is sufficient to allow normal migration of GAD65-GFP expressing interneurons into the neocortex.

Fig. 8. Dlx1/2-Cre, Nex-Cre, and Emx1-Cre drivers delete expression of the EB2-lz-encoded EB2-βgal fusion protein in select cell populations in the embryonic forebrain.

Images of WT or EB2-lz/lz brains containing the GAD65-GFP reporter, Rosa-STOP-tdTomato (Ai9) indicator, and indicated Cre driver collected at E15.5. Shown are isolated images of X-gal stains in bright-field, Tom and GFP fluorescence in confocal, and merged signals. Asterisks identify the ganglionic eminences noting the X-gal staining for EB2 expression is present in the inhibitory neuron population in the EB2-lz, EB2-lz + Nex-Cre, and EB2-lz + Emx1-Cre embryos, but visibly absent in the EB2-lz + Dlx1/2-Cre embryo. Also note that the GAD65-GFP signal is appreciably more intense in the WT and EB2-lz + Dlx1/2-Cre sections, as the prominent X-gal staining for EB2 expression in the ganglionic eminences masks the GFP signal in the EB2-lz, EB2-lz + Nex-Cre, and EB2-lz + Emx1-Cre embryos. Arrows identify the neocortex noting the X-gal staining for EB2 expression is present only in the inner/deeper layers in the EB2-lz + Nex-Cre embryo and is completely absent in the neocortex of the EB2-lz + Emx1-Cre embryo.

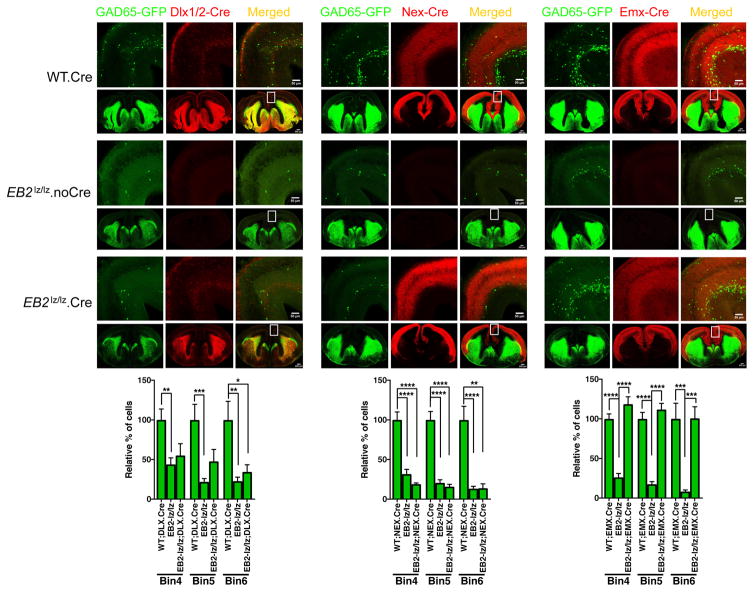

Fig. 9. Ephrin-B2 functions as a non-autonomous ligand to direct interneuron migration in the neocortex.

Female mice heterozygous for the EB2-lz mutation and homozygous for the Rosa26-STOP-tdTomato (Ai9) Cre indicator were crossed to male mice also heterozygous for the EB2-lz mutation and carrying the GAD65-GFP reporter and one of the following Cre drivers: Dlx1/2-Cre (inhibitory neurons), Nex-Cre (excitatory neurons), and Emx1-Cre (excitatory neurons and radial glial cells) to induce formation of EB2-T mutants in the corresponding cell types. Shown are representative low and high magnification confocal images of GAD65-GFP labeled cells from WT.Cre (upper panels), EB2-lz/lz (middle panels), and EB2-lz/lz.Cre (lower panels) collected at E15.5. Quantification of GAD65-GFP cells is shown at the bottom. No rescue in the migration of GAD65-GFP interneurons into bins 4, 5, and 6 was observed in the EB2-lz/lz mutants that also contain the Dlx1/2-Cre driver (left) or Nex-Cre driver (middle), while striking rescue was observed in the EB2-lz/lz mutants that also contain the Emx-Cre driver. N values for embryonic brain hemispheres: WT.Dlx1/2-Cre (8), EB2-lz/lz.Dlx1/2-Cre (4), WT.Nex-Cre (14), EB2-lz/lz.Nex-Cre (10), WT.Emx-Cre (14), EB2-lz/lz.Emx-Cre (6), EB2-lz/lz (12); mean ± s.e.m.; one-way ANOVA (post-hoc Tukey test); * P< 0.05, ** P< 0.01, *** P<0.001, **** P<0.0001.

The rescue of interneuron migration by the Emx1-Cre driver was further analyzed in EB2lz/+ heterozygotes, which in the absence of a Cre driver also exhibit a significant reduction in migration of GAD65-GFP and GAD67-GFP interneurons into the neocortex. Here, consistent with the above results, a strong rescue of GAD65-GFP interneuron migration defect was observed in the presence of the Emx-Cre driver (Fig. S12A). Interestingly, Emx1-Cre was not able to rescue the reduced migration of GAD67-GFP interneurons in the EB2lz/+ heterozygote (Fig. S12B). These results indicate that the migration of GAD65 interneurons, but not GAD67 interneurons, are under the influence of EB2 ligand-like activity stemming from radial glial cells.

Discussion

It is thought that disruptions in brain development are often central to many types of psychiatric disorders and intellectual disabilities, likely by affecting the populations, organization, integration, and balance of cortical excitatory and inhibitory neurons to allow for proper E/I homeostasis and the formation of functional neural circuits. Great progress has been made in recent years through the identification of genes that contribute to psychiatric disorders and intellectual disabilities in humans, including reports that implicate the highly conserved neuronal EphB2 receptor tyrosine kinase in autism (Kong et al., 2012; Sanders et al., 2012), anxiety disorders (Attwood et al., 2011), and Alzheimer’s disease (Cisse et al., 2011). Despite these advancements, our knowledge of the molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways that help build neural circuits and shape higher order brain functions that may go awry in psychiatric disorders remains rudimentary. To gain a better understanding of the potential involvement of the EphB receptors and their cognate ephrin-B ligands in brain development, we focused on the three ephrin-B proteins and identified key roles for these molecules in the early migration of cortical interneurons. Summarized in Fig. 10, we find the ephrin-B proteins play a fascinating dual role by acting both as receptors expressed on interneurons to transduce cell autonomous reverse signals important for their migration and as ligands expressed on cortical radial glial cells to stimulate non-cell autonomous forward signals needed for interneuron migration. Disruption of these bidirectional signals leads to highly significant reductions in the migration of interneurons into the neocortex, which ultimately affects their ability to populate the mature brain, leading to cortical hyperexcitability and seizures. Our data allows us to hypothesize that EphB/ephrin-B cell-cell signaling is an essential component for migration of interneurons in the developing brain and for the formation of normal cortical E/I balance.

Fig. 10.

Summary of results indicating both forward and reverse signaling are involved in the migration of interneurons into the neocortex.

Our findings are supported by a thorough in vivo analysis of the three ephrin-B’s. First, we determined that all three are expressed on inhibitory neurons in the developing forebrain, being detected on both GAD67-GFP and GAD65-GFP labeled groups. Second, to identify cell autonomous functions we generated conditional triple mutant brains in which all three Efnb genes are deleted specifically in inhibitory neurons and demonstrate this leads to greatly reduced migration of both GAD67 and GAD65 interneurons into the neocortex, resulting in cortical hyperexcitability and lethal seizures. Third, consistent with cell autonomous reverse signaling roles for these molecules in interneurons, we analyzed intracellular truncation and point mutations in Efnb2 and Efnb3 and found that these also lead to strong reduction in migration of both GAD67 and GAD65 interneurons into the neocortex with hyperexcitability and seizures. And fourth, consistent with its expression also in cortical excitatory neurons and radial glial cells, we demonstrate ephrin-B2 exhibits a non-cell autonomous ligand-like role in the migration of interneurons into the neocortex. The idea that the EB2lz-encoded EB2-βgal fusion protein can act as a dominant overactive ‘super-ligand’ to promote excessive forward signaling is consistent with our recent report on lymphatic valve development (Zhang et al., 2015). Interesting, our data suggests that GAD65-GFP interneurons are selectively under the influence of this ligand-like activity, likely by activating forward signaling within inter neuron-expressed Eph receptors. Candidate Eph receptors expressed in inhibitory interneurons include EphB1, EphB2, EphB3, EphB6, and EphA4 (Fig. S5 and Data File S1) (Rudolph et al., 2014; Villar-Cervino et al., 2015; Zimmer et al., 2011). Moreover, in recent experiments, we find that EphB1−/− protein-null knockouts (Williams et al., 2003) and EphB1T-lacZ/T-lacZ mutants which truncate the EphB1 intracellular kinase domain (Chenaux and Henkemeyer, 2011) both selectively exhibit a reduced population of GAD65-GFP interneurons without any reductions in the GAD67-GFP group (unpublished data). We thus conclude that the migration of GAD67 interneurons are mainly under the influence of reverse signaling, whereas GAD65 interneurons utilize both reverse and forward signals to migrate into the neocortex.

Previous reports of ephrin-B involvement in interneuron migration centered only on ephrin-B3 and mainly relied on in vitro experiments and only analyzed one embryonic time point (E14) showing a very mild phenotype at best without any analysis of adult populations (Rudolph et al., 2014; Zimmer et al., 2011). Our in depth in vivo analysis indicates ephrin-B3 alone has little if any effect on interneuron migration as we failed to notice any consistent abnormality in the EB3 single mutants in embryos using either GAD67-GFP or GAD65-GFP reporters. Rather, our Dlx1/2-Cre conditional analysis using TMlz and TM analysis indicate involvement of all three ephrin-B molecules working as a team within both of these groups of interneurons to direct their migration into the neocortex. Further, our analysis of intracellular truncation and point mutations indicates ephrin-B2 is the more powerful player compared to ephrin-B1 or ephrin-B3 in the migration of both GAD67-GFP and GAD65-GFP interneurons. It is worth noting that we find a large proportion of forebrain inhibitory neurons express ephrin-B2 in the embryonic brain (Fig. 1E). Regarding the GAD67-GFP-positive interneuron class, we found the EB2lz/lz single mutants alone showed strong reduction in migration in bins 4–6 that was not exaggerated by addition of EB3lz/lz in the double mutant. However, this may be due to developmental delay in migration as we found in the adult brain only EB2lz/6YFΔV;EB3lz/lz double mutants showed significant reductions in GAD67-GFP interneurons, indicating overlapping/redundant activities for these two molecules. It is more difficult to draw conclusions on the role of reverse signaling on GAD65-GFP class interneurons in the embryo using the EB2lz mutation as these cells are under influence of both ephrin-B2 reverse and forward signaling. Nevertheless, we found that both EB2lz/6YFΔV single mutants and EB2lz/6YFΔV; EB3lz/lz double mutants exhibited reductions in GAD65-GFP cells in the adult brain, indicating ephrin-B2 reverse signaling may be predominant for this class of interneurons, though we cannot exclude the possibility of some ‘super-ligand’ activity remaining in the EB2lz/6YFΔV mutant combination. We were surprised to find that EB26YFΔV/6YFΔV; EB3lz/lz double mutants exhibited normal migration of GAD65-GFP interneurons in the embryo and only modest reductions in the GAD67-GFP group. Unfortunately, we cannot assess the interneuron populations in the EB26YFΔV/6YFΔV adult brain because the ‘weak-ligand’ activity in the homozygotes provides too little forward signaling for lymphatic/blood vessels and animal viability. Nevertheless, the results observed in the embryo indicate that SH2/PDZ binding domains of ephrin-B2 reverse signaling are not absolutely required for interneuron migration and raises the possibility that other phosphorylation sites such as serine residues in the intracellular domain, or perhaps other binding and signaling avenues (e.g. Par6, Connexin43, and Claudins), are involved in the migration of interneurons (Daar, 2012). Furthermore, it is entirely possible that additional modes or components of EphB/ephrin-B cell-cell signaling are at play during interneuron migration, including involvement of trans-endocytosis, downstream Rho/Rac/Cdc42 signaling, or perhaps even Eph-independent mechanisms (Lisabeth et al., 2013). Future studies will be needed to address these possibilities.

Regarding the role of ephrin-B2 as a cortical-expressed ligand to stimulate forward signaling, we note that both excitatory neurons (deleted by Nex-Cre and Emx1-Cre drivers) and radial glial cells (deleted by Emx1-Cre only) express very high levels of this molecule inside the embryonic cortical wall. However, rescue of EB2lz/lz-encoded EB2-βgal ‘super-ligand’ activity was only observed in the embryos that contained the Emx1-Cre driver. While this indicates that radial glial expressed EB2 is the most important compartment needed for ligand-like activity, it remains possible that deletion of ‘super-ligand’ is needed in both radial glial cells as well as excitatory neurons. We further note that cortical-expressed EB2 is not absolutely essential for interneuron migration as the EB2lz/lz.Emx1-Cre brains in which EB2-βgal ‘super-ligand’ activity is turned into the EB2-T trans-Golgi trapped protein-null showed normal ‘rescued’ levels GAD65-GFP migration. This indicates other cortical-expressed ephrin ligands may be at play to compensate for the loss of EB2 to help regulate migration of interneurons in the neocortex. Further along this thought, it is curious that reductions in interneuron distribution were observed in the hippocampal CA1 region, but not in CA3 region. How is it possible that interneurons fail to populate CA1 though they can migrate through it to populate CA3 with apparently no problem? We believe it is possible that once interneurons have globally migrated into the hippocampal zone there may be additional localized roles for EphB/ephrin-B cell-cell signaling in the final distribution of an interneuron to a particular hippocampal region and layer.

Conclusion

The disruption of E/I homeostasis has gained wide recognition as a central theme in psychiatric disorders such as epilepsy, autism, other intellectual disabilities, schizophrenia, anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, and depression. Because our knowledge of the molecular genetic elements of such disorders of the mind is still rudimentary, many more participants are likely to be discovered and need to be fully explored. Our studies of the three ephrin-B proteins indicate these potent signaling molecules work collectively as a team to ensure normal distribution and function of inhibitory interneurons in the brain and that genetic (and possible environmental) perturbations that alter their expression or activities can lead to cortical hyperexcitability and seizures with profound effects.

Materials and Methods

Mice

All mice used in this analysis have been previously described; GAD65-GFP (Lopez-Bendito et al., 2004) and GAD67-GFP (Tamamaki et al., 2003) reporters, doxycycline-inducible (dox) Tg-BAC-ephrin-B1rtTA transgene (Robichaux et al., 2014), TetO-tdTomato indicator (Li et al., 2010), loxP-flanked alleles in ephrin-B1 (EB1loxP) (Davy et al., 2004) and ephrin-B2 (EB2loxP) (Gerety and Anderson, 2002), ephrin-B2lz (EB2lz) and ephrin-B2T (EB2T) (Dravis et al., 2004), ephrin-B26YFΔV (EB26YFΔV) (Thakar et al., 2011), ephrin-B3lz (EB3lz) (Yokoyama et al., 2001), Dlx1/2-Cre (Potter et al., 2009), Nex-Cre (Goebbels et al., 2006), Emx1-Cre (Iwasato et al., 2000), and Rosa26-STOP-tdTomato Cre indicator (Ai9)(Madisen et al., 2010). Mice were maintained in a mixed CD1/129 genetic background. All experiments involving mice were carried out in accordance with the US National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Animals under an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved protocol and at an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care approved facility at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Animals were generated by M.H. and all brain tissues collected, fixed (if required for the experiment), and genotyped by M.H. and F.S. who then provided all samples to be analyzed in a blinded fashion to A.T., R.B., S.A., and A.B. Genotypes were unlocked only after completion of analysis.

Embryonic and adult brains

Embryos were obtained from timed pregnant females and collected on ice in PBS (PBS; 4.3mM Na2HPO4, 1.4 mM KH2PO4, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.4) between the hours of 2:00–6:00 PM CST. Brains were dissected and fixed in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde (Extra pure ACROS Organics #416780010; Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) made in PBS overnight on a Nutator at 4°C in the dark. Embryonic brains were then washed multiple times with PBS and stored in the dark in PBS containing 0.05% sodium azide at 4°C.

Adult mouse brains were collected around postnatal day 90 (P90). Mice were anesthetized using 225 mg/kg Ketamine and 25 mg/kg Xylazine mixture in PBS and perfused with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Brains were collected and post-fixed overnight in the dark in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and then washed multiple times with PBS and then stored in PBS containing 0.05% sodium azide in the dark at 4°C.

Fixed brains were embedded in 3% agarose and 40–50 μm coronal sections were cut with a vibratome (frequency 7 Hz, speed 5 Hz). All slices of embryonic age were selected from rostral to caudal orientation, approximately 0.5–1 mm of telencephalon region with approximately 0.5 mm thickness giving around 10–12 slices. Slices of adult brains were selected between interaural 2.36 mm - 1.64 mm (Bregma −1.43 to −2.15 mm) with approximately 700 um thickness giving around 12–15 slices. Slices were placed in 24-well plates (1–2 slices in each) in PBS containing 0.05% sodium azide and maintained in the dark at 4°C until used for direct imaging of GFP and tdTomato fluorescence signals after mounting on charged slides using an aqueous mounting solution (Immu-Mount #9990402, Thermo Scientific, USA).

Some brains were also sectioned on a cryostat by first cryoprotecting overnight in 30% sucrose in PBS at 4°C and were then frozen in OCT (Tissue-Tek O.C.T compound, Sakura Finetek USA Inc., Ca, USA) using slushy dried-ice in ethanol. Cryosections of 10 μm were cut (Leica Microsystem GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) and allowed to air dry on slides at RT in the dark. Sections were then washed 3 × 10 min in PBS at RT to remove OCT, coverslipped, and imaged.

Immunofluorescence and X-gal stain

Free floating vibratome brain sections were placed in 24-well plates with blocking solution (4% donkey serum/4% goat serum/0.1% Triton X-100 in 1x PBS) for 1 hour at RT and then probed with primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution overnight at 4°C. Primary antibodies were used in following dilutions; rabbit anti-β-galactosidase (1:10000; Cappel #559761), rabbit anti-Ki67 (1:200; Thermo-Scientific #PA5-19462), rabbit anti-cleaved caspase 3 (1:2000; Cell Signaling # #9661). Sections were then washed 3 × 10 min in PBST (PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20) and probed with fluorescent secondary antibodies (1:500) for 1 hour at RT. Sections were then washed in PBST 3 × 10 min and mounted on charged slides using an aqueous mounting solution (Immu-Mount #9990402, Thermo Scientific, USA). For anti-β-galactosidase antibody staining, floating sections were blocked overnight at 4°C in enhanced blocking solution (8% donkey serum/4% BSA/0.3% Triton X-100 in 1x PBS) and then probed with primary antibody in enhanced blocking solution for 48 hours at 4°C, washed 2 × 10min in PBST and another wash overnight in PBST containing 0.3% Triton at 4°, before being probed with secondary antibodies and mounted as above.

For X-gal stain, free floating vibratome slices were placed in 24-well plates and incubated in X-gal staining solution (5 mM potassium ferri-cyanide/5 mM potassium ferro-cyanide, 2mM MgCl2, 1 mg/ml X-gal in 1x PBS) overnight at 37°C on a Nutator. Sections were washed 3 × 10 min in 1x PBS on the next day, mounted on slides, coverslipped, and imaged.

Neuron cultures

Pregnant female mice were euthanized and embryos removed from the abdomen, decapitated, and each forebrain was dissected and placed in a sterile microtube on ice. A solution of 300 μl of 0.05% trypsin–EDTA (Invitrogen) was added and tissue was incubated 15 min in a 37°C water bath, followed by addition of 600 μl DMEM medium containing 10% FBS, cells triturated 15 times, and then cell suspension was filtered (70μm mesh), centrifuged gently at 900 RPM at RT, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 1 ml DMEM containing 10% FBS and counted. Approximately 50 × 103 cells were plated and incubated at 37°C for 2–3 days. Cells were washed 3 times with cold PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at RT, washed 3 times with PBS, and subjected to immunofluorescent analysis or X-gal staining.

Neuron counts and statistical analysis

Neurons were imaged using a Zeiss LSM710 confocal laser-scanning microscope also equipped for bright-field capture. For embryonic brains, the number of cells in the cortical wall of different bins 4–6 were counted in three sections of each hemisphere (1 rostral, 1 medial, 1 caudal). Bins 1–3 were not counted because at the ages selected to conduct analysis of bins 4–6 there were too many labeled cells to accurately count in bins 1–3. For adult brains, cells were counted from 3 sections of each hemisphere spanning the rostral, medial, and caudal zone of the hippocampus and the quantification areas in cortex and hippocampus were selected as follows: 1.0 mm2 of cortex through layers I–VI was selected starting approximately 1.0 mm distance from the brain midline, 0.5 mm2 for CA1, 0.5 mm2 for DG, and 0.75 mm2 for CA3. Since there was variation in neuron counts between left and right hemispheres in the embryonic and adult sections, each hemisphere was counted independently. All cell counts were performed using ImageJ software (Rasband, National Institutes of Health, USA) and graphs were made in GraphPad Prism 6 and 7 software. Statistical analysis was performed using student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA with multiple comparison post-hoc Tukey test. The number of mouse brains are indicated in each figure legend and data in all graphs are represented as mean ± SEM. A P-value <0.05 was considered as a significant difference between means, but a range of P-value in each comparison are shown by stars in each graph (* P< 0.05, ** P< 0.01, *** P<0.001, **** P<0.0001). The actual cell count data is provided in Tables S1–S7.

Electrophysiology

The following method is essentially identical as previously described (Hays et al., 2011). Dissected brains from P20–P24 mice were transferred into ice-cold dissection buffer (87mM NaCl, 3mM KCl, 1.25mM NaH2PO4, 26mM NaHCO3, 7mM MgCl2, 0.5mM CaCl2, 20mM D-glucose, 75mM sucrose and 1.3mM ascorbic acid) saturated with 95% O2–5% CO2 and then sectioned on an angled block to obtain thalamo-cortical slices (400 μm) using a vibratome (Leica Vibratome 1200s). Slices containing primary somatosensory cortex were immediately transferred to an interface recording chamber (Harvard Instruments) and allowed to recover for 1 hr in ACSF (126mM NaCl, 3mM KCl, 1.25mM NaH2PO4, 26mM NaHCO3, 2mM MgCl2, 2mM CaCl2, and 25mM D-glucose) at 32°C. Slices were then perfused with a modified ACSF that better mimics physiological ionic concentrations in vivo (Gibson et al., 2008; Sanchez-Vives and McCormick, 2000) containing (126mM NaCl, 5mM KCl, 1.25mM NaH2PO4, 26mM NaHCO3, 1mM MgCl2, 1mM CaCl2, and 25mM D-glucose). Slices remained in this modified ACSF for 1 hr prior to recordings.

Spontaneously generated UP states in vitro were recorded in layer IV using 0.5 MΩ tungsten microelectrodes (FHC, Bowdoinham, ME) placed in layer 4 (IV) of primary somatosensory cortex for 10 min. Recordings were amplified 10,000-fold, sampled at 2.5 kHz, and filtered on-line between 300Hz and 3kHz. All measurements were analyzed off-line using custom Labview software. For visualization and analysis of UP states, traces were offset to zero, rectified, and low-pass filtered with a 0.2 Hz cutoff frequency. Using these processed traces, the threshold for detection was set at 5x the RMS noise, and an event was defined as an UP state if its amplitude remained above the threshold for at least 200 ms. The end of the UP state was determined when the amplitude decreased below threshold for >600 ms. Two events occurring within 600ms of one another were considered part of a single UP state. These criteria best accounted for the simultaneous occurrence and identical durations of UP states. UP state amplitude was unitless since it was normalized to the detection threshold. For all UP state experiments, a minimum of 3 mice were used per genotype, and on average, 8 slices were examined per mouse.

Audiogenic seizures

Individual mice (P20–24) were transported to a sound isolated procedure room and placed in a plastic chamber (30 × 19 × 12 cm) containing a >110-dB siren (Swann Doorstop Alarm, SWHOM-DOORST). The cage was covered with a styrofoam lid and 110-dB siren was presented for 3.5 min. Mice were monitored/videotaped and scored for behavioral grades: 0 = no response (walking, cleaning, standing), 1 = wild running, 2 = tonic-clonic seizures (non-lethal seizure), 3 = status epilepticus (lethal seizure). The ears of the tester were covered with sound shielding headphones. Fisher’s exact test was used to assess the results.

Rotarod learning

Mice were placed on a stationary rotarod (IITC Life Science Inc) which was then accelerated from 5 to 45 rpm over five minutes. The time that each mouse falls from the rod is recorded. If a mouse holds onto the rod and rotates completely around two times, it is considered to have fallen from the rod at that time. Each mouse is tested four times a day for two consecutive days with a 15–30 min intertrial interval.

Locomotor activity

Locomotion activity was evaluated by two different protocols. To measure beam breaks, mice were placed individually into a clean, plastic mouse cage (18 cm × 28 cm) with minimal bedding, which was placed into a dark Plexiglas box. Movement was monitored by 5 photobeams in one dimension (Photobeam Activity System, San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA) for 2 hours, with the number of beam breaks recorded every 5 min. To measure beam crossing mice were placed at one end of elevated 1-meter beams of 18mm, 9mm, and 5mm rods. A black box was fixed at the end of beam with home cage-nesting material in the box to attract mice, and a light source above the start point as aversive stimulus. Video cameras were fixed at 0cm and 80cm above beam to record performance and measure average time for two successful trials to cross the beam with no stopping/stalling and the number of foot slips.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

All three ephrin-B’s are expressed in inhibitory neurons in the developing brain.

Receptor-like ephrin-B reverse signaling is required for interneuron migration.

Ephrin-B2 is also expressed in cortical neurons and radial glial cells.

Ligand-like ephrin-B2 forward signaling is also involved in interneuron migration.

EphB/ephrin-B bidirectional signaling establishes excitatory-inhibitory homeostasis.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following for providing/generating specific mouse lines: Philippe Soriano and Alice Davy for Efnb1loxP, David Anderson for Efnb2loxP, John Rubenstein for Dlx1/2-Cre (I12b), Klaus-Armin Nave for Nex-Cre, Takuji Iwasato for Emx1-Cre (KIΔNeo), Liqun Luo for TetO-tdTomato (TRE-Bi-SG-T), and Hongkui Zeng for Rosa26-STOP-tdTomato (Ai9). We thank Robert Silvany for help with FACS analysis. This research was supported by the NIH (MH066332) to M.H.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Animals were raised and generated by M.H., embryonic brain tissues were collected and fixed by M.H., adult brains were fixed and collected by F.S., genotyping was done by F.S., analysis of interneuron migration and population in embryonic/adult brains was done by A.T., analysis of cell death was done by A.B., audiogenic seizure tests were done by R.B., electrophysiology was done by S.A. and J.G., the GAD65-GFP mouse was provided by G.S., the GAD67-GFP mouse and microarray data was provided by N.T. The manuscript was written by A.T. and M.H.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andrews W, Barber M, Hernadez-Miranda LR, Xian J, Rakic S, Sundaresan V, Rabbitts TH, Pannell R, Rabbitts P, Thompson H, Erskine L, Murakami F, Parnavelas JG. The role of Slit-Robo signaling in the generation, migration and morphological differentiation of cortical interneurons. Dev Biol. 2008;313:648–658. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwood BK, Bourgognon JM, Patel S, Mucha M, Schiavon E, Skrzypiec AE, Young KW, Shiosaka S, Korostynski M, Piechota M, Przewlocki R, Pawlak R. Neuropsin cleaves EphB2 in the amygdala to control anxiety. Nature. 2011;473:372–375. doi: 10.1038/nature09938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista-Brito R, Fishell G. The developmental integration of cortical interneurons into a functional network. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2009;87:81–118. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(09)01203-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett KM, Afanador MD, Lal CV, Xu H, Persad E, Legan SK, Chenaux G, Dellinger M, Savani RC, Dravis C, Henkemeyer M, Schwarz MA. Ephrin-B2 reverse signaling increases alpha5beta1 integrin-mediated fibronectin deposition and reduces distal lung compliance. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;49:680–687. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0002OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Toth M. Fragile X mice develop sensory hyperreactivity to auditory stimuli. Neuroscience. 2001;103:1043–1050. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00036-7. S0306452201000367 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenaux G, Henkemeyer M. Forward signaling by EphB1 EphB2 interacting with ephrin-B ligands at the optic chiasm is required to form the ipsilateral projection. European J Neuroscience. 2011;34:1620–1633. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07845.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisse M, Halabisky B, Harris J, Devidze N, Dubal DB, Sun B, Orr A, Lotz G, Kim DH, Hamto P, Ho K, Yu GQ, Mucke L. Reversing EphB2 depletion rescues cognitive functions in Alzheimer model. Nature. 2011;469:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature09635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CA, Henkemeyer M. Ephrins in reverse, park and drive. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:339–346. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02317-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CA, Yokoyama N, Saxena A, Chumley MJ, Silvany RE, Baker LA, Srivastava D, Henkemeyer M. Ephrin-B2 reverse signaling is required for axon pathfinding and cardiac valve formation but not early vascular development. Dev Biol. 2004;271:263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daar IO. Non-SH2/PDZ reverse signaling by ephrins. Seminars in Cell & Dev Biol. 2012;23:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davy A, Aubin J, Soriano P. Ephrin-B1 forward and reverse signaling are required during mouse development. Genes Dev. 2004;18:572–583. doi: 10.1101/gad.1171704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolen G, Osterweil E, Rao BS, Smith GB, Auerbach BD, Chattarji S, Bear MF. Correction of fragile X syndrome in mice. Neuron. 2007;56:955–962. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dravis C, Henkemeyer M. Ephrin-B reverse signaling controls septation events at the embryonic midline through separate tyrosine phosphorylation-independent signaling avenues. Dev Biol. 2011;355:138–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dravis C, Yokoyama N, Chumley MJ, Cowan CA, Silvany RE, Shay J, Baker LA, Henkemeyer M. Bidirectional signaling mediated by ephrin-B2 and EphB2 controls urorectal development. Dev Biol. 2004;271:272–290. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faingold CL. Role of GABA abnormalities in the inferior colliculus pathophysiology - audiogenic seizures. Hear Res. 2002;168:223–237. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00373-8. S0378595502003738 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flames N, Long JE, Garratt AN, Fischer TM, Gassmann M, Birchmeier C, Lai C, Rubenstein JL, Marin O. Short- and long-range attraction of cortical GABAergic interneurons by neuregulin-1. Neuron. 2004;44:251–261. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman DM, Marin O. Generation of interneuron diversity in the mouse cerebral cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:2136–2141. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerety SS, Anderson DJ. Cardiovascular ephrinB2 function is essential for embryonic angiogenesis. Development. 2002;129:1397–1410. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.6.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson JR, Bartley AF, Hays SA, Huber KM. Imbalance of neocortical excitation and inhibition and altered UP states reflect network hyperexcitability in the mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:2615–2626. doi: 10.1152/jn.90752.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebbels S, Bormuth I, Bode U, Hermanson O, Schwab MH, Nave KA. Genetic targeting of principal neurons in neocortex and hippocampus of NEX-Cre mice. Genesis. 2006;44:611–621. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider B, McCormick DA. Rapid neocortical dynamics: cellular and network mechanisms. Neuron. 2009;62:171–189. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays SA, Huber KM, Gibson JR. Altered neocortical rhythmic activity states in Fmr1 KO mice are due to enhanced mGluR5 signaling and involve changes in excitatory circuitry. J Neurosci. 2011;31:14223–14234. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3157-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasato T, Datwani A, Wolf AM, Nishiyama H, Taguchi Y, Tonegawa S, Knopfel T, Erzurumlu RS, Itohara S. Cortex-restricted disruption of NMDAR1 impairs neuronal patterns in the barrel cortex. Nature. 2000;406:726–731. doi: 10.1038/35021059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong A, Frigge ML, Masson G, Besenbacher S, Sulem P, Magnusson G, Gudjonsson SA, Sigurdsson A, Jonasdottir A, Jonasdottir A, Wong WS, Sigurdsson G, Walters GB, Steinberg S, Helgason H, Thorleifsson G, Gudbjartsson DF, Helgason A, Magnusson OT, Thorsteinsdottir U, Stefansson K. Rate of de novo mutations and the importance of father’s age to disease risk. Nature. 2012;488:471–475. doi: 10.1038/nature11396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullander K, Klein R. Mechanisms and functions of Eph and ephrin signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:475–486. doi: 10.1038/nrm856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy LM, Degnan AJ. GABA-based evaluation of neurologic conditions: MR spectroscopy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:259–265. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA, Hashimoto T, Volk DW. Cortical inhibitory neurons and schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:312–324. doi: 10.1038/nrn1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Tasic B, Micheva KD, Ivanov VM, Spletter ML, Smith SJ, Luo L. Visualizing the distribution of synapses from individual neurons in the mouse brain. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11503. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisabeth EM, Falivelli G, Pasquale EB. Eph Receptor Signaling and Ephrins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a009159. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Bendito G, Sturgess K, Erdelyi F, Szabo G, Molnar Z, Paulsen O. Preferential origin and layer destination of GAD65-GFP cortical interneurons. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:1122–1133. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]