Abstract

AIM

To evaluate the evolution, trends in surgical approaches and reconstruction techniques, and important lessons learned from performing 1000 consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies (PDs) for periampullary tumors.

METHODS

This is a retrospective review of the data of all patients who underwent PD for periampullary tumor during the period from January 1993 to April 2017. The data were categorized into three periods, including early period (1993-2002), middle period (2003-2012), and late period (2013-2017).

RESULTS

The frequency showed PD was increasingly performed after the year 2000. With time, elderly, cirrhotic and obese patients, as well as patients with uncinate process carcinoma and borderline tumor were increasingly selected for PD. The median operative time and postoperative hospital stay decreased significantly over the periods. Hospital mortality declined significantly, from 6.6% to 3.1%. Postoperative complications significantly decreased, from 40% to 27.9%. There was significant decrease in postoperative pancreatic fistula in the second 10 years, from 15% to 12.7%. There was a significant improvement in median survival and overall survival among the periods.

CONCLUSION

Surgical results of PD significantly improved, with mortality rate nearly reaching 3%. Pancreatic reconstruction following PD is still debatable. The survival rate was also improved but the rate of recurrence is still high, at 36.9%.

Keywords: Pancreaticoduodenectomy, Pancreaticogastrostomy, Pancreaticojejunostomy, Postoperative pancreatic fistula, Periampullary tumor

Core tip: Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is a complex abdominal procedure. The hospital mortality rate has decreased to less than 5%; however, the rate of postoperative morbidities remains high, from 40% to 50%. Pancreatic reconstruction following PD is still debatable. The long survival rate after PD is clearly improved with time but still poor. Frequency showed PD is increasingly performed. With time, elderly, cirrhotic and obese patients, and patients with uncinate process carcinoma and borderline tumor are increasingly selected for PD. Median operative time and postoperative hospital stay decreased significantly. Hospital mortality declined significantly, from 6.6% to 3.1%. Postoperative complications significantly decreased.

INTRODUCTION

The first successful localized resection of periampullary tumor was performed by Dr William S Halsted in 1898. For the first time, Allen O Whipple described pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) in the year 1935, when he modified the procedure that was performed before by Alessendro Codinivillan in Italy and Walter Keusch in Germany[1,2]. In 1963, Whipple performed 37 PDs in his era. From this era till 1980, PD was infrequently performed because the hospital mortality was high (> 25%). After 1990, with development of high-volume centers and improvement of operative technique, surgical equipment, and perioperative care, PD has become a relatively safe and commonly performed procedure[3-5].

PD is one of the most complex abdominal operations that is performed for a heterogeneous group of periampullary lesions, either benign or malignant. PD involves extensive dissection, resection and different reconstruction procedures[3-8]. The rate of postoperative morbidities remains high, from 40% to 50%. However, the hospital mortality rate has decreased to less than 5% in many published series[5-8,9-11].

Many studies were performed to determine the risk factors of post-operative pancreatic fistula and try to present a fistula risk scoring system after PD. These various systems used many factors including pancreatic duct diameter, consistency of pancreas, body mass index (BMI) > 25 kg/m2, and final pathology[4-6,11-15]. Pancreatic reconstruction following PD is still debatable, even for pancreatic surgeons. Ideally, pancreatic reconstruction after PD should reduce the risk of post-operative pancreatic fistula (POPF) and its severity if developed with preservation of pancreatic functions (exocrine and endocrine functions)[5-8].

The prognosis of pancreatic head adenocarcinoma is one of the most dismal of all cancers. After PD, the 5-year survival is 5% to 20%, representing the worst survival among the periampullary cancers. Numerous prognostic factors have been found to improve survival rate after PD, including lymph node status, free safety margins, tumor size, differentiation, complete excision of mesopancreas, and vascular invasion[11-14].

Many points are still debatable regarding PD, including selection of patients, pancreatic reconstruction, and factors that improve survival rate. Thus, the aim of this study was to evaluate the evolution, trends in surgical approaches and reconstruction techniques, and important lessons learned from performing 1000 consecutive PD for periampullary tumors in the Gastrointestinal Surgery Center of Mansoura University over a period of 25 years.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This is a retrospective review of the data of all patients who underwent PD for periampullary tumor in the Gastrointestinal Surgery Center (Mansoura University, Egypt) during the period from January 1993 to April 2017. Patient data were recorded in a prospectively maintained database for all patients undergoing PD since the year 2000; for patients from before 2000, the data were obtained from the archived files. An informed consent for the surgical procedures was obtained from each patient. The Gastrointestinal Surgery Center of Mansoura University is a high-volume center of pancreatic surgery that was established in 1992. The first PD was performed in 1993, and was regularly performed afterwards in our center over a period of 25 years.

Inclusion criteria

This study included 1000 patients who underwent PD for different periampullary tumors (benign and malignant lesions) at our Center in Mansoura University, Egypt during the period from January 1993 to April 2017. Over the 25-year period, 1000 consecutive PD were performed by 20 surgeons. For this study, the data were categorized into three periods, early period (1993-2002), middle period (2003-2012), and late period (2013-2017). This study was approved by the local institutional review board (IRB).

Exclusion criteria

Patients with periampullary lesions who were explored during the same period and failed to complete the PD procedure due to the presence of locally advanced or distant metastatic disease that was not detected in preoperative radiological workup.

Preoperative assessment

Preoperative diagnostic workup included clinical assessment, detailed laboratory investigations, including tumor markers, and radiological investigations (abdominal ultrasound, abdominal triphasic computed tomography (CT), CT angiography, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, chest X-ray and bone survey). Preoperative biliary drainage was performed by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in selected patients[16].

Surgical procedures

Over the study period and with accumulating experience, evolution of the surgical approach and techniques occurred.

Dissection technique

In the early period, the anterior approach was utilized in surgical dissection. Afterwards, we shifted to utilize the posterior approach (one of the artery first approaches), aiming to identify vascular invasion at an early stage of the dissection, and to allow more radical excision of the mesopancreas[17]. Standard regional lymphadenectomy was performed, which included resection of nodes within the outlines of the hepatoduodenal ligament, right side of the superior mesenteric vessels, and inferior vena cava. In the early period, diathermy dissection and ligatures were used during the resection stage. Afterwards, a shift to use modern energy devices occurred, such as for Ligasure and Harmonic scalpel.

Approach

In most of our study period, we utilized an open surgical approach through extended right subcostal or inverted J incisions. In the late period, we started to utilize laparoscopic approach, with laparoscopy-assisted approach used in the beginning. This included complete dissection by the laparoscopy followed by reconstruction carried out through a small upper midline or transverse incision. In the last year, we performed a total of 10 laparoscopic PDs. This included completing the whole approach (dissection and reconstruction) by laparoscopy.

Meso-pancreatectomy

A complete removal of all lympho-vascular tissues between the uncinate process and superior mesenteric artery was mandatory in PD. These tissues are the most important site for local recurrence after PD. This concept had evolved in the recent years and became a standard step in the radical resection of periampullary tumors. We adopted this concept in the recent years of our study.

Division of the pancreatic neck

Initially, we divided the pancreatic neck sharply by surgical scalpel and then carried out the hemostasis after division. Recently, we started to divide the pancreatic neck by diathermy and Harmonic scalpel.

Reconstruction

In the beginning of our series, we performed simple loop pancreaticojejunostomy (PJ) for the reconstruction of the pancreatic stump. However, a high rate of pancreatic fistula was noticed. A shift of the reconstruction plan occurred to pancreaticogastrostomy (PG). Short-term outcomes were improved and lower rate of pancreatic fistula was noticed, but the long-term outcomes regarding the digestive and nutritional conditions were not appropriate.

With accumulating experience and refinement of the surgical technique, a re-shift to PJ (simple loop or isolated loop) occurred, which improved long-term outcomes[18,19]. Recently, we adopted a tailored approach for pancreatic stump management. In patients at high risk of pancreatic fistula (presence of two or more risk factors) PG is preferred. In low- and moderate-risk patients (absence of risk factors or presence of one risk factor) PJ is preferred.

Postoperative management

All patients were transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) postoperatively. Antibiotics and analgesic were given to all patients. Octreotide analogue was given to some patients postoperatively. Abdominal drains and nasogastric tubes outputs were recorded daily. Patients started oral feeding once bowel sounds restarted and they were able to tolerate nutrition by a fluid diet, then a regular diet.

Abdominal ultrasound was done routinely in all patients postoperatively. Serum amylase and liver function tests were measured on postoperative day (POD) 1 and POD 5. Ultrasound-guided tubal drainage was carried out in patients who had an abdominal collection.

Follow-up occurred at 1 wk, 3 mo and 6 mo postoperatively, and then at 1 year. Patients were also seen at outpatient clinics if symptoms developed between follow-up visits.

Definitions

Complications were defined as adverse events resulting in deviation from the normal postoperative course within 30 d after operation. Severity of complications was assessed using the Clavien classification system, from 1 to 5. Major complications represent those requiring endoscopic, radiologic or surgical intervention, and were defined as class 3 or higher[20].

Postoperative pancreatic fistula was defined by International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula as any measurable volume of fluid on or after POD 3 with amylase content greater than three times the serum amylase activity, and classified into three grades: A, B or C[21-23].

Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) was defined as output from a nasogastric tube of greater than 500 mL per day that persisted beyond POD 10, the failure to maintain oral intake by POD 14, or reinsertion of a nasogastric tube[21-24].

Outcomes of the study

The aim of this study was to evaluate the milestones, trends in surgical approaches, reconstruction techniques and important lessons learned from performing 1000 consecutive PD for periampullary tumors in the Gastrointestinal Surgery Center of Mansoura University over a period of 25 years. The main outcome of the study was the rates of postoperative morbidity, according to Clavien-Dindo classifications, and of mortality after PD. Special concern was focused on POPF, biliary complications, DGE and the predictive factors of each. In addition, we evaluated the survival outcomes of the PD patients, including recurrence, overall survival (OS) and the different predictive factors of each.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the data in this study was performed using SPSS software for windows, version 20. For continuous variables, descriptive statistics were calculated and reported as median. Categorical variables were described using frequency distributions. The χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables and one-way ANOVA for continuous variables. The predictive factors for postoperative complications were evaluated by binary logistic regression method. Survival outcomes were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method. The predictive factors for survival were evaluated by the Cox regression method. P values < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

RESULTS

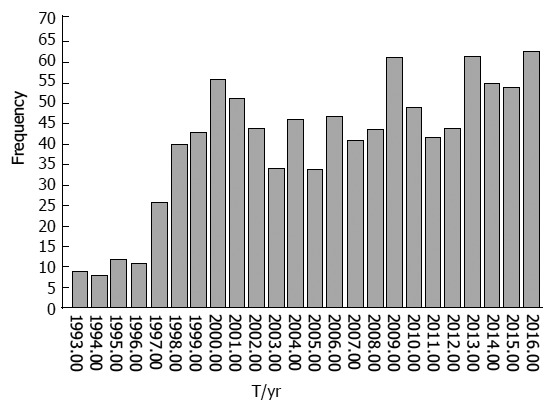

One thousand patients underwent PD for resection of periampullary tumors from January 1993 to April 2017. Of the 1000 patients who underwent PD, 556 involved pancreatic head mass, 312 were ampullary tumors, 61 were duodenal tumors, 41 were cholangiocarcinoma and 30 were uncinate process mass. The median age of patients was 54-years-old. The data were categorized into three periods. For the first 10 years (1993-2002), a total of 300 patients underwent PD (30 cases/year). In the next 10 years (2003-2012), the total number was 442 patients who underwent PD (44.2 cases/year). In the last 5 years (2013-2017), the total number was 258 patients who underwent PD (51.6 cases/year) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

In the first 10 years (1993-2002), the total number of patients who underwent PD was 300 (30 cases/yr), in the next 10 years (2003-2012) 442 patients underwent PD (44.2 cases/yr), and in the last 4 years (2013-2017) 258 cases underwent PD (51.6 cases/yr).

Preoperative data

Elderly patients were increasingly selected for PD, as the median age was 53 in the first 10 years and 55 in the last 5 years. Obese patients were increasingly selected in the last five years. There were no significant changes for selection of patients for PBD in the period of the study. PBD was indicated for patients with high serum bilirubin (> 10 mg%) with high liver enzymes, renal impairment or associated cholangitis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and preoperative data

| Variable | Total, n = 1000 | First 10 yr, 1993-2002 | Second 10 yr, 2003-2012 | Last 5 yr, 2013-2017 | P-value |

| Age in yr | 54 (12-88) | 53 | 55 | 55 | 0.22 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 614 (61.4) | 190 (63.3) | 260 (58.8) | 164 (63.6) | 0.33 |

| Female | 386 (38.6) | 110 (36.7) | 182 (41.2) | 94 (36.4) | |

| DM | 145 (14.5) | 39 (13) | 60 (13.6) | 46 (17.8) | 0.21 |

| BMI in kg/m2 | |||||

| < 25 | 723 (72.3) | 250 (38.3) | 326 (73.8) | 147 (57) | 0.0001 |

| > 25 | 277 (27.7) | 50 (16.7) | 116 (26.2) | 111 (43) | |

| Abdominal pain | 753 (75.3) | 230 (76.7) | 329 (74.4) | 194 (74.2) | 0.12 |

| Jaundice | 909 (90.9) | 265 (88.3) | 406 (91.9) | 238 (92.2 | 0.18 |

| Preoperative biliary drainage | 511 (51.1) | 163 (54.5) | 226 (51.1) | 122 (47.3) | 0.23 |

| Preoperative serum albumin in mg | 4 (3.2-5.2) | 4.1 | 4 | 3.9 | 0.23 |

| Preoperative serum bilirubin in mg | 4 (0.5-38) | 3.1 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 0.0001 |

| Preoperative CEA | 6.4 (0.5-394) | 8 | 8 | 6 | 0.09 |

| Preoperative CA19-9 | 27 (0.5-1200) | 32 | 33 | 34 | 0.12 |

Data are presented as n (%) or n (range), unless otherwise indicated. BMI: Body mass index; CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen; DM: Diabetes mellitus.

Intraoperative data

Patients with periampullary tumors and well-compensated chronic liver disease were increasingly selected for PD (Table 2). In the early period, we performed simple loop PJ (21.7%) for the reconstruction of the pancreatic stump, then shifted to PG (78.3%). In the second 10 years, 94.3% of cases underwent PG. In the last 5 years, there was a re-shift to PJ (simple loop or isolated loop) (46.1%). Complete meso-pancreatecomy was achieved in all cases in the last 5 years Operative time was significantly reduced, from 6 h in the first 10 years to 5 h in last 5 years. The median intraoperative blood loss decreased from 500 cc in the first 10 years to 300 cc in last 5 years.

Table 2.

Operative data

| Variable | Total, n = 1000 | First 10 yr, 1993-2002 | Second 10 yr, 2003-2012 | Last 5 yr, 2013-2017 | P-value |

| Cirrhosis | 129 (12.9) | 28 (9.3) | 62 (14) | 39 (15.1) | 0.009 |

| Mass size in cm | 3 (0.5-15) | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| < 2 | 418 (41.8) | 123 (41) | 174 (39.4) | 123 (46.9) | 0.14 |

| > 2 | 582 (58.2) | 177 (59) | 268 (60.6) | 137 (53.1) | |

| Pancreatic texture | |||||

| Soft | 596 (59.6) | 190 (63.3) | 263 (59.5) | 143 (55.4) | 0.23 |

| Firm | 404 (40.4) | 110 (36.7) | 179 (40.5) | 115 (44.6) | |

| Median pancreatic duct diameter in mm | 5 (1-15) | 0.47 | |||

| < 3 | 313 (31.3) | 97(32.3) | 137 (30.9) | 79 (30.6) | |

| > 3 | 687 (68.7) | 20367.7) | 305 (60.1) | 179 (69.4) | |

| Pancreatic duct to posterior border in mm | 0.45 | ||||

| < 3 | 421 (42.1) | 128 (42.7) | 185 (41.9) | 108 (41.9) | |

| > 3 | 579 (57.9) | 172 (57.3) | 257 (58.1) | 150 (58.1) | |

| Pancreatic stump mobilization in cm | 2 (1-4) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.45 |

| CBD diameter in mm | 15 (5-30) | 15 | 15 | 15 | 0.06 |

| Type of reconstruction | |||||

| PG | 791 (79.1) | 235 (78.3) | 417 (94.3) | 139 (53.9) | 0.0001 |

| Simple PJ | 163 (16.3) | 65 (21.7) | 25 (5.7) | 73 (28.3) | |

| Isolated loop PJ | 46 (4.6) | 0 | 0 | 46 (17.8) | |

| Duct to mucosa | 134 (13.4) | 9 (3) | 65 (14.7) | 60 (23.3) | |

| Invaginated type with duct to mucosa | 644 (64.4) | 234 (78) | 250 (65.6) | 160 (62) | 0.0001 |

| Invaginated type without duct to mucosa | 221 (22.1) | 57 (19) | 126 (28.5) | 38 (14.7) | |

| No anastomosis | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 0 | |

| Standard approach | 908 (90.8) | 277 (92.3) | 388 (87.8) | 243 (94.7) | 0.004 |

| Posterior approach | 92 (9.2) | 23 (7.7) | 54 (12.2) | 15 (5.8) | |

| Complete meso-pancreatectomy | 574 (57.4) | 83 (27.7) | 233 (52.7) | 258 (100) | 0.0001 |

| Laparoscopic assisted PD | 11 (1.1) | 0 | 0 | 11 (4.3) | 0.0001 |

| Complete laparoscopic PD | 10 (1) | 0 | 0 | 10 (3.9) | |

| Vascular resection | 12 (1.2) | 0 | 4 (0.9) | 8 (3.1) | 0.003 |

| Primary anastomosis | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.7) | 8 (3.1) | |

| Gortex | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 0 | |

| Operative time in h | 5 (3.5-10) | 6 | 5 | 5 | 0.001 |

| Blood loss in cc | 500 (50-4000) | 500 | 400 | 300 | 0.001 |

Data are presented as n (%) or n (range). PD: Pancreaticoduodenectomy; PG: Pancreaticogastrostomy; PJ: Pancreaticojejunostomy.

Postoperative data

The overall morbidity of all 1000 patients was 32.3%. The postoperative complications decreased markedly in the recent years, from 40% to 27.9%. There was a significant decrease in POPF in the second 10 years, from 15% to 12.7% with a decrease in the severity. But the incidence of POPF increased again in last 5 years to 14.7%. DGE was the most common complication (18%). It was secondary to other postoperative complications in 15.2%. Primary DGE presented in 2.8% of cases (Table 3).

Table 3.

Postoperative data

| Variable | Total, n = 1000 | First 10 yr, 1993-2002 | Second 10 yr, 2003-2012 | Last 5 yr, 2013-2017 | P-value |

| Hospital stay in d | 8 (5-71) | 9 | 8 | 8 | 0.0001 |

| Time to oral intake in d | 5 (4-56) | 6 | 5 | 5 | 0.33 |

| Total amount of drainage in mL | 700 (40-35000) | 1200 | 600 | 600 | 0.0001 |

| Drain removal in d | 8 (4-71) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 0.03 |

| Total postoperative complications | 323 (32.3) | 120 (40) | 131 (29.6) | 72 (27.9) | 0.02 |

| Dindo grade | |||||

| I | 114 (11.4) | 24 | 47 | 43 | |

| II | 97 (9.7) | 40 | 45 | 12 | 0.11 |

| III | 69 (6.9) | 36 | 24 | 9 | |

| IV and V | 43 (4.3) | 20 | 15 | 8 | |

| Severe complications, ≥ III | |||||

| Minor | 211 (21.1) | 84 | 92 | 55 | 0.23 |

| Major | 109 (10.9) | 56 | 69 | 17 | |

| Pancreatic fistula | 139 (13.9) | 45 (15) | 56 (12.7) | 38 (14.7) | 0.01 |

| Grade A | 67 (6.7) | 14 | 33 | 20 | 0.04 |

| Grade B | 48 (4.8) | 20 | 17 | 11 | |

| Grade C | 24 (2.4) | 11 | 6 | 7 | |

| DGE | 180 (18) | 76 (25.3) | 67 (15.2) | 37 (14.3) | 0.06 |

| Types of DGE | |||||

| Secondary DGE | 152 (15.2) | 70 (23.3) | 54 (12.2) | 27 (10.5) | 0.03 |

| Primary DGE | 28 (2.8) | 5 (1.7) | 13 (2.9) | 10 (3.9) | |

| Pulmonary complications | 46 (4.6) | 20 (6.7) | 21 (4.8) | 5 (1.6) | 0.01 |

| Bile leak | 73 (7.3) | 39 (13) | 19 (4.3) | 15 (5.8) | 0.001 |

| Postoperative bleeding | 25 (2.5) | 13 (4.3) | 7 (1.6) | 5 (1.9) | 0.49 |

| Pancreatitis | 20 (2) | 12 (4.3) | 7 (1.6) | 1 (0.4) | 0.004 |

| Bleeding PG | 15 (1.5) | 8 (2.7) | 5 (1.2) | 2 (0.8) | 0.14 |

| Wound infection | 50 (5) | 13 (4.6) | 25 (5.7) | 12 (4.7) | 0.77 |

| Re-operation | 74 (7.4) | 25 (8.3) | 33 (7.5) | 16 (6.2) | 0.21 |

| Recurrence | 321 (36.9) | 130 (50.4) | 125 (32.6) | 66 (28.7) | 0.0001 |

| Hospital mortality | 43 (4.3) | 20 (6.6%) | 15 (3.4) | 8 (3.1) | 0.02 |

| Postoperative chemoradiotherapy | 275 (27.5) | 0 | 132 (29.9) | 143 (55.4) | 0.0001 |

| Overall median survival in mo | 26 (1-300) | 21 | 30 | 37 | 0.0001 |

| 1 yr | 90% | 87% | 93% | 87% | |

| 3 yr | 33% | 19% | 37% | 64% | |

| 5 yr | 19% | 11% | 21% |

Data are presented as n (%) or n (range), unless otherwise indicated. DGE: Delayed gastric emptying; PG: Pancreaticogastrostomy.

The median hospital stay and the day of drain removal were significantly shortest in the late period, decreasing from 9 days to 8 days. The overall hospital mortality of all 1000 patients was 4.3% (43 patients). The hospital mortality declined significantly, from 6.6% to 3.1%. The causes of death were sepsis secondary to POPF in 17 patients, with 6 cases due to cardiac arrest, 6 cases due to liver cell failure, 5 cases due to pulmonary embolism, 3 cases due to pancreatitis, 3 cases due to respiratory failure secondary to severe chest infection, 2 cases due to secondary hemorrhage, and 1 case due to PG–related uncontrolled bleeding.

Seventy patients developed intra-abdominal collection and were managed by ultrasound-guided tubal drainage. Seventy-four patients (7.4%) required re-explorations due to internal hemorrhage (26 patients, with 7/26 due to erosion of gastroduodenal artery), bleeding GJ (17 patients), bleeding PG (15 patients), peritonitis (12 patients) or debridement and drainage (4 patients). Completion spleno-pancreatectomy was needed in 2 cases due to POPF that eroded the gastroduodenal artery and were complicated by secondary internal hemorrhage

The overall recurrence rate in 870 patients who had malignant pathology after PD was 36.9.2%. This rate decreased from 50.4% to 28.7%

Univariate analysis of risk factors for development of POPF found that six variables were significantly associated with POPF (BMI > 25 kg/m2, liver cirrhosis, soft pancreas, main pancreatic duct < 3 mm, pancreatic duct close to posterior edge < 3 mm, and period of the study). These six risk factors of POPF identified in univariate analysis were further analyzed in multivariate analysis. Soft pancreas, main pancreatic duct < 3 mm pancreatic duct close to posterior edge < 3 mm, BMI > 25 kg/m2 and period of the study were found to be independent risk factors (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of risk factors of development of post-operative pancreatic fistula

| Univariate | Multivariate | Exp(B) |

95%CI for Exp(B) |

||

| P-value | P-value | Lower | Upper | ||

| Age grouping > 60 yr | 0.2 | ||||

| Sex | 0.99 | ||||

| DM | 0.58 | ||||

| BMI >25 kg/m2 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 6.468 | 4.193 | 9.977 |

| Preoperative serum bilirubin > 10 mg% | 0.62 | ||||

| Preoperative ERCP | 0.52 | ||||

| Liver cirrhosis | 0.05 | 0.328 | 0.699 | 0.341 | 1.434 |

| Size of the tumor > 2 cm | 0.91 | ||||

| Soft pancreas | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.218 | 0.14 | 0.341 |

| Pancreatic duct diameter > 3 mm | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.182 | 0.118 | 0.279 |

| Pancreatic duct closely related to posterior border of pancreas > 3 mm | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.372 | 0.243 | 0.57 |

| Blood loss > 1000 mL | 0.67 | ||||

| Blood transfusion | 0.94 | ||||

| Type of pancreatic reconstruction | 0.62 | ||||

| Duration of operation | 0.75 | ||||

| Site of the tumor | 0.34 | ||||

| Period of the study | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.615 | 0.461 | 0.82 |

BMI: Body mass index; DM: Diabetes mellitus; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Postoperative pathology

There was significant difference among groups regarding site of periampullary tumor, type of pathology, number of dissected lymph nodes, number of infiltrated lymph nodes, lymph node ratio, safety margin, perivascular infiltration and perineural invasion (Table 5).

Table 5.

Postoperative pathology n (%)

| Variable | Total, n = 1000 | First 10 yr, 1993-2002 | Second 10 yr, 2003-2012 | Last 5 yr, 2013-2017 | |

| Site of the tumor | |||||

| Ampullary tumor | 312 (31.2) | 92 (30.7) | 145 (32.8) | 75 (29) | |

| Pancreatic head mass | 556 (55.6) | 171 (57) | 257 (58.1) | 128 (49.6) | 0.0001 |

| CBD duct tumor | 41 (4.1) | 16 (5.3) | 13 (2.9) | 12 (4.7) | |

| Duodenal tumor | 61 (6.1) | 20 (6.7) | 27 (6.1) | 14 (5.4) | |

| Uncinate process mass | 30 (3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 29 (11.3) | |

| Pathological diagnosis | |||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 836 (83.6) | 250 (83.3) | 357 (80.7) | 229 (88.8) | |

| Undifferentiated carcinoma | 20 (2) | 1 (1.7) | 19 (4.3) | 0 | |

| Papillary cystadenocarcinoma | 6 (0.6) | 4 (1.3) | 2 (0.5) | 0 | 0.0001 |

| Lymphoma | 4 (0.4) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) | 0 | |

| Neuroendocrine tumor | 28 (2.8) | 12 (4) | 10 (2.3) | 6 (2.3) | |

| Solid pseudopapillary tumor | 20 (2) | 5 (1.7) | 8 (1.8) | 7 (2.7) | |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 24 (2.4) | 6 (2) | 14 (3.2) | 4 (1.6) | |

| Benign cyst | 12 (1.2) | 3 (1) | 8 (1.8) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Adenoma with dysplasia | 41 (4.1) | 15 (5) | 19 (4.3) | 7 (2.7) | |

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | 2 (0.2) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Glomus | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | |

| Adenosquamous | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | |

| Pleomorphic adenoma | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 1(0.2) | 0 | |

| Adenomyoma | 3 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 3 (1.2) | |

| Malignant | 870 (87) | 258 (86) | 382 (86.4) | 230 (89.1) | 0.38 |

| Borderline | 48 (4.8) | 17(5.7) | 18 (4.1) | 13 (5.1) | |

| benign | 82 (8.2) | 25 (8.3) | 42 (9.5) | 15 (5.8) | |

| Number of dissected lymph node | 6 (0-40) | 5 (0-18) | 6 (0-40) | 6 (0-40) | 0.59 |

| Number of lymph node infiltration | 0 (0-14) | 0 (0-3) | 0 (0-14) | 0 (0-14) | 0.07 |

| Perineural infiltration | 187 (18.7) | 62 (20.7) | 75 (17) | 50 (19.9) | 0.09 |

| Perivascular infiltration | 134 (134) | 40 (13.3) | 66 (14.9) | 28 (10.9) | 0.13 |

| Pancreatic safety margin | |||||

| R1 | 91 (9.1) | 40 (13.3) | 41 (9.3) | 10 (3.8) | 0.01 |

| R2 | 15 (1.5) | 7 (2.3) | 6 (1.4) | 2 (0.7) |

survival rate

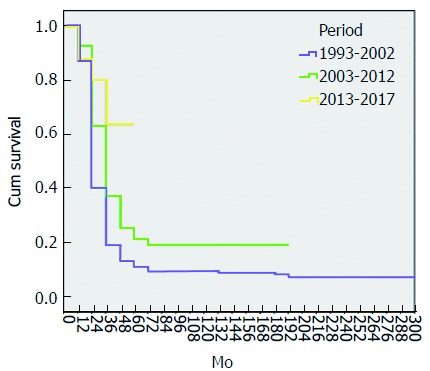

The 1-, 3- and 5-year OS rates for all cases were 90%, 33% and 19% respectively, with a median survival of 26 mo. There was a significant difference among the groups regarding the median survival and the OS rates at 1-, 3- and 5-years (tables 3 and 6, Figure 2). The survival analysis in this study revealed that female sex, patients who did not develop major complications, presence of ampullary tumor, type of pathology, negative safety margin, negative lymph nodes, chemoradiotherapy and period of the study were all favorable prognostic variables in univariate and multivariate analyses. The improvement of survival with recent years may be due to complete excision of mesopancreas, greater use of postoperative chemoradiotherapy, improvement of surgical techniques, and strict follow up of most of cases (table 6).

Figure 2.

Overall survival curves of patients according to the 3 periods of study. The overall survival rate significantly improved and 5-yr survival rate for the early period was 11%, followed by 21% for the middle period and 64% for the late period (P = 0.0001)

DISCUSSION

PD is a complex procedure including extensive dissection, resection and multiple reconstruction. Allen O Whipple described PD in the year 1935. From Whipple’s era till 1980, PD was performed infrequently because the hospital mortality was high above 25%[2].

Patient selection is still an important factor in decreasing postoperative morbidity and mortality. In our series, the frequency of PD had been increasingly performed after the year 2000. Elderly patients were increasingly selected for PD, as the median age was 53 years in the first 10 years and became 55 years in the last 5 years. In the last 5 years, we accepted patients over the age of 75.

The significant improvement in the surgical outcome of PD has encouraged surgeons to approach periampullary tumors as aggressively in elderly patients[7,12]. Patients with periampullary tumors and well-compensated chronic liver disease are increasingly selected for PD with accepted surgical outcomes. PD is only recommended in patients with Child A cirrhosis without portal hypertension[13]. PD is associated with an increased risk of postoperative morbidity in obese patients. With time, obesity has lost its status as a limitation for PD and such patients have been increasingly selected[25-27].

Patients with uncinate process carcinoma are increasingly selected for PD as well. However, the loco-regional recurrence rate was found to be common and the OS rate to be lower than other periampullary tumors[28]. The role of postoperative chemoradiotherapy may improve the results. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer should be included as an indication of PD with advancements in chemoradiotherapy and techniques of vascular resection[29].

The impact of PBD on postoperative outcomes remains controversial. PBD before PD was associated with major postoperative morbidities and stent-related morbidities, including infection, pancreatitis or adhesions. There are no significant changes for selection of patients for PBD in the period of the study. PBD is indicated for patients with high serum bilirubin (> 10 mg%) with high liver enzymes, renal impairment, or associated cholangitis[16,30,31].

In our Center, laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy (LPD) has been introduced as a feasible alternative to open PD since 2013, involving dissection in some cases, then complete LPD was performed at the end of 2013; unfortunately, however, the patients died on POD 7. We restarted again in January 2016 to perform 10 complete LPDs; in all cases, the pancreatic reconstruction was PG. The median operative time was 8 h, so the procedure was performed by two teams (one team for complete dissection and the other one to perform all reconstruction). Only one hospital mortality occurred due to severe pancreatitis, and all cases passed smoothly without any complications. The median hospital stay was 5 days. The most important point to performing a safe LPD is to perform the procedure under skilled hands in selected patients and using suitable surgical techniques[32,33].

The ideal and safe pancreatic reconstruction following PD is still debatable. We performed a comparative randomized study between PG and isolated loop PJ which revealed no significant difference between both methods in regards to POPF, but the pancreatic function was preserved with isolated loop PJ[18,19]. Recently, with accumulating experience and refinement of the surgical technique, we adopted a tailored approach for the management of pancreatic stump management. Another prospective randomized study comparing duct to mucosa and invagination PJ carried out in our center concluded that invagination PJ is preferred in small pancreatic duct and provides less incidence of postoperative steatorrhea and was associated with less severity of POPF, if developed, than duct to mucosa[19].

In our series, 32.3% of patients undergoing PD had complications. The majority of complications were minor and not life threatening. The postoperative complications decreased markedly in the recent years, from 40% to 27.9%. There was significant decrease in POPF in the second 10 years, from 15% to 12.7% with decrease in severity due to shift of pancreatic reconstruction from PJ to PG. But, the incidence of POPF increased again in last 5 years to 14.7%, due to re-shift again to PJ in order to achieve better long-term outcomes regarding function and morphology of pancreas[18,19]. In this study, the development of major complications had a negative impact on OS.

The median hospital stay was significantly shortest in the last 10 years. In many high-volume centers, there has been significant decrease in postoperative stay after PD as a result of the increase in the frequency of PD, the decrease in incidence of complications, especially of DGE, the decrease in use of pylorus-preserving PD, which is complicated by high incidence of DGE, and the improvements in postoperative care and management of postoperative complications[6,7,34-36].

In this study, the overall hospital mortality was 4.3%. Of the patients who died, 17/43 (39.5%) of the deaths were due to sepsis secondary to POPF. The decrease in hospital mortality following PD over the time is the most prominent achievement in PD. In this study, the hospital mortality rate decreased significantly from 6.6% to 3.1%, which is comparable to the reported mortality rates in other high-volume centers[6-8].

Long-term survival after PD for periampullary tumor adenocarcinoma is still poor. However, the survival after PD has clearly improved with time, due to improvement of surgical techniques, complete excision of mesopancreas, greater use of neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant chemoradiotherapy, and strict follow up of most of cases. There are many high-volume centers in which patients with pancreatic head carcinoma treated by PD have a 5-year survival rate of around 20%[6,7,35,36].

In conclusion, the frequency of PD has increased and become a relatively safe procedure in our Center. With time, elderly, cirrhotic, obese patients, patients with uncinate process carcinoma and borderline tumors have been increasingly selected for PD. Surgical results of PD, including operative time, hospital stay and postoperative complications, have significantly improved, with the mortality rate reaching nearly 3%. Pancreatic reconstruction following PD is still debatable. PG provides better short-term outcomes including POPF, but the long-term outcomes regarding the pancreatic function and nutrition were not appropriate. However, PJ provides better long-term outcomes. The survival rate also improved due to complete meso-pancreatectomy and utilization of adjuvant chemoradiotherapy, but the rate of recurrence is still high at 36.9%. LPD has been introduced as a feasible alternative to open PD.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Egypt

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mansoura University.

Informed consent statement: Informed consent was obtained from all patients to undergo pancreaticoduodenectomy after a careful explanation of the nature of the disease and possible complications.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Peer-review started: May 18, 2017

First decision: June22, 2017

Article in press: August 2, 2017

P- Reviewer: Elpek GO, Katuchova J, Zhang J S- Editor: Ma YJ

L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Ayman El Nakeeb, Gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt. elnakeebayman@man.edu.eg.

Waleed Askar, Gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt..

Ehab Atef, Gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt..

Ehab El Hanafy, Gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt..

Ahmad M Sultan, Gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt..

Tarek Salah, Gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt..

Ahmed shehta, Gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt..

Mohamed El Sorogy, Gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt..

Emad Hamdy, Gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt..

Mohamed El Hemly, Gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt..

Ahmed A El-Geidi, Gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt..

Tharwat Kandil, Gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt..

Mohamed El Shobari, Gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt..

Talaat Abd Allah, Gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt..

Amgad Fouad, Gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt..

Mostafa Abu Zeid, Gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt..

Ahmed Abu El Eneen, Gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt..

Nabil Gad El-Hak, Gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt..

Gamal El Ebidy, Gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt..

Omar Fathy, Gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt..

Ahmed Sultan, Gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt..

Mohamed Abdel Wahab, Gastroenterology surgical center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt..

References

- 1.Kausch W. Das carcinoma der papilla duodeni und senineradikaleentfeinung. Beitr 2. ClincChir. 1912;78:439e486. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whipple AO. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for Islet Carcinoma : A Five-Year Follow-Up. Ann Surg. 1945;121:847–852. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194506000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takagi K, Yagi T, Yoshida R, Shinoura S, Umeda Y, Nobuoka D, Kuise T, Watanabe N, Sui K, Fujii T, et al. Surgical Outcome of Patients Undergoing Pancreaticoduodenectomy: Analysis of a 17‒Year Experience at a Single Center. Acta Med Okayama. 2016;70:197–203. doi: 10.18926/AMO/54419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kimura W, Miyata H, Gotoh M, Hirai I, Kenjo A, Kitagawa Y, Shimada M, Baba H, Tomita N, Nakagoe T, et al. A pancreaticoduodenectomy risk model derived from 8575 cases from a national single-race population (Japanese) using a web-based data entry system: the 30-day and in-hospital mortality rates for pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2014;259:773–780. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El Nakeeb A, Salah T, Sultan A, El Hemaly M, Askr W, Ezzat H, Hamdy E, Atef E, El Hanafy E, El-Geidie A, et al. Pancreatic anastomotic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Risk factors, clinical predictors, and management (single center experience) World J Surg. 2013;37:1405–1418. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-1998-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cameron JL, Riall TS, Coleman J, Belcher KA. One thousand consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies. Ann Surg. 2006;244:10–15. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000217673.04165.ea. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron JL, He J. Two thousand consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:530–536. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He J, Ahuja N, Makary MA, Cameron JL, Eckhauser FE, Choti MA, Hruban RH, Pawlik TM, Wolfgang CL. 2564 resected periampullary adenocarcinomas at a single institution: trends over three decades. HPB (Oxford) 2014;16:83–90. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshioka R, Yasunaga H, Hasegawa K, Horiguchi H, Fushimi K, Aoki T, Sakamoto Y, Sugawara Y, Kokudo N. Impact of hospital volume on hospital mortality, length of stay and total costs after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 2014;101:523–529. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balzano G, Zerbi A, Capretti G, Rocchetti S, Capitanio V, Di Carlo V. Effect of hospital volume on outcome of pancreaticoduodenectomy in Italy. Br J Surg. 2008;95:357–362. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Wilde RF, Besselink MG, van der Tweel I, de Hingh IH, van Eijck CH, Dejong CH, Porte RJ, Gouma DJ, Busch OR, Molenaar IQ; Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group. Impact of nationwide centralization of pancreaticoduodenectomy on hospital mortality. Br J Surg. 2012;99:404–410. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El Nakeeb A, Atef E, El Hanafy E, Salem A, Askar W, Ezzat H, Shehta A, Abdel Wahab M. Outcomes of pancreaticoduodenectomy in elderly patients. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2016;15:419–427. doi: 10.1016/S1499-3872(16)60105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El Nakeeb A, Sultan AM, Salah T, El Hemaly M, Hamdy E, Salem A, Moneer A, Said R, AbuEleneen A, Abu Zeid M, et al. Impact of cirrhosis on surgical outcome after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:7129–7137. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i41.7129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winter JM, Cameron JL, Campbell KA, Arnold MA, Chang DC, Coleman J, Hodgin MB, Sauter PK, Hruban RH, Riall TS, et al. 1423 pancreaticoduodenectomies for pancreatic cancer: A single-institution experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1199–1210; discussion 1210-1211. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vallance AE, Young AL, Macutkiewicz C, Roberts KJ, Smith AM. Calculating the risk of a pancreatic fistula after a pancreaticoduodenectomy: a systematic review. HPB (Oxford) 2015;17:1040–1048. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El Nakeeb A, Salem A, Mahdy Y, El Dosoky M, Said R, Ellatif MA, Ezzat H, Elsabbagh AM, Hamed H, Alah TA, et al. Value of preoperative biliary drainage on postoperative outcome after pancreaticoduodenectomy: A case-control study. Asian J Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdel-Wahab M, Sultan A, elGwalby N, Fathy O, AboElenen A, Zied MA, Fouad A, Allah TA, el-Ebiedy G, Gad-ElHak N, et al. Modified pancreaticoduodenectomy: experience with 81 cases, Wahab modification. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:1572–1576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El Nakeeb A, Hamdy E, Sultan AM, Salah T, Askr W, Ezzat H, Said M, Zeied MA, Abdallah T. Isolated Roux loop pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a prospective randomized study. HPB (Oxford) 2014;16:713–722. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El Nakeeb A, El Hemaly M, Askr W, AbdEllatif M, Hamed H, Elghawalby A, Attia M, Abdallah T, AbdElWahab M. Comparative study between duct to mucosa and invagination pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a prospective randomized study. Int J Surg. 2015;16:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M; International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula Definition. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, Sarr M, Abu Hilal M, Adham M, Allen P, Andersson R, Asbun HJ, Besselink MG, Conlon K, Del Chiaro M, Falconi M, Fernandez-Cruz L, Fernandez-Del Castillo C, Fingerhut A, Friess H, Gouma DJ, Hackert T, Izbicki J, Lillemoe KD, Neoptolemos JP, Olah A, Schulick R, Shrikhande SV, Takada T, Takaori K, Traverso W, Vollmer CR, Wolfgang CL, Yeo CJ, Salvia R, Buchler M; International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 Years After. Surgery. 2017;161:584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeOliveira ML, Winter JM, Schafer M, Cunningham SC, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Clavien PA. Assessment of complications after pancreatic surgery: A novel grading system applied to 633 patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2006;244:931–937; discussion 937-939. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000246856.03918.9a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McMillan MT, Malleo G, Bassi C, Sprys MH, Ecker BL, Drebin JA, Vollmer CM Jr. Pancreatic fistula risk for pancreatoduodenectomy: an international survey of surgeon perception. HPB (Oxford) 2017;19:515–524. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2017.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams TK, Rosato EL, Kennedy EP, Chojnacki KA, Andrel J, Hyslop T, Doria C, Sauter PK, Bloom J, Yeo CJ, et al. Impact of obesity on perioperative morbidity and mortality after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El Nakeeb A, Hamed H, Shehta A, Askr W, El Dosoky M, Said R, Abdallah T. Impact of obesity on surgical outcomes post-pancreaticoduodenectomy: a case-control study. Int J Surg. 2014;12:488–493. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsai S, Choti MA, Assumpcao L, Cameron JL, Gleisner AL, Herman JM, Eckhauser F, Edil BH, Schulick RD, Wolfgang CL, et al. Impact of obesity on perioperative outcomes and survival following pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer: a large single-institution study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1143–1150. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1201-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.El Nakeeb A, Roshdy S, Ask W, Sonbl A, Ali M, Abdelwahab K, Shams N, Abdelwahab M. Comparative study between uncinate process carcinoma and pancreatic head carcinoma after pancreaticodudenectomy (clincopathological features and surgical outcomes) Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61:1748–1755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen KT, Devarajan K, Milestone BN, Cooper HS, Denlinger C, Cohen SJ, Meyer JE, Hoffman JP. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation and duration of chemotherapy before surgical resection for pancreatic cancer: does time interval between radiotherapy and surgery matter? Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:662–669. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3396-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Addeo P, Rosso E, Fuchshuber P, Oussoultzoglou E, De Blasi V, Simone G, Belletier C, Dufour P, Bachellier P. Resection of Borderline Resectable and Locally Advanced Pancreatic Adenocarcinomas after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Oncology. 2015;89:37–46. doi: 10.1159/000371745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arkadopoulos N, Kyriazi MA, Papanikolaou IS, Vasiliou P, Theodoraki K, Lappas C, Oikonomopoulos N, Smyrniotis V. Preoperative biliary drainage of severely jaundiced patients increases morbidity of pancreaticoduodenectomy: results of a case-control study. World J Surg. 2014;38:2967–2972. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2669-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stauffer JA, Coppola A, Villacreses D, Mody K, Johnson E, Li Z, Asbun HJ. Laparoscopic versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: long-term results at a single institution. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:2233–2241. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5222-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jin WW, Xu XW, Mou YP, Zhou YC, Zhang RC, Yan JF, Zhou JY, Huang CJ, Lu C. [Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy: a report of 233 cases by a single team] Zhonghua WeiKe ZaZhi. 2017;55:354–358. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-5815.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.El Nakeeb A, Askr W, Mahdy Y, Elgawalby A, El Sorogy M, Abu Zeied M, Abdallah T, AbdElwahab M. Delayed gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Risk factors, predictors of severity and outcome. A single center experience of 588 cases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:1093–1100. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2795-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balcom JH 4th, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL, Chang Y, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Ten-year experience with 733 pancreatic resections: changing indications, older patients, and decreasing length of hospitalization. Arch Surg. 2001;136:391–398. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.4.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmidt CM, Powell ES, Yiannoutsos CT, Howard TJ, Wiebke EA, Wiesenauer CA, Baumgardner JA, Cummings OW, Jacobson LE, Broadie TA, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy: a 20-year experience in 516 patients. Arch Surg. 2004;139:718–725; discussion 725-727. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.7.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]