Summary

Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) are natural polyesters of increasing biotechnological importance that are synthesized by many prokaryotic organisms as carbon and energy storage compounds in limiting growth conditions. PHAs accumulate intracellularly in form of inclusion bodies that are covered with a proteinaceous surface layer (granule‐associated proteins or GAPs) conforming a network‐like surface of structural, metabolic and regulatory polypeptides, and configuring the PHA granules as complex and well‐organized subcellular structures that have been designated as ‘carbonosomes’. GAPs include several enzymes related to PHA metabolism (synthases, depolymerases and hydroxylases) together with the so‐called phasins, an heterogeneous group of small‐size proteins that cover most of the PHA granule and that are devoid of catalytic functions but nevertheless play an essential role in granule structure and PHA metabolism. Structurally, phasins are amphiphilic proteins that shield the hydrophobic polymer from the cytoplasm. Here, we summarize the characteristics of the different phasins identified so far from PHA producer organisms and highlight the diverse opportunities that they offer in the Biotechnology field.

Introduction

Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) are natural polyesters produced and accumulated by diverse organisms from the Bacteria and Archaea kingdoms as energy and carbon storage compounds under nutrient limitation conditions (i.e. nitrogen, oxygen or phosphorus) but in the presence of an excess of carbon sources (Anderson and Dawes, 1990; Lee, 1996). These polymers have acquired notoriety in recent years because they display plastic properties similar to their oil‐derived counterparts, but show biodegradability and biocompatibility features which results in a versatile and eco‐friendly alternative (Madison and Huisman, 1999; Potter and Steinbuchel, 2006; Keshavarz and Roy, 2010). PHAs were first described by M. Lemoigne in France, who in the 1920s reported the presence of poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate) [P(3HB)], in the cytoplasm of Bacillus megaterium (Lemoigne, 1926). Since then, over 300 species, including both Gram‐positive and Gram‐negative bacteria, have been described with the metabolic ability to synthesize PHAs (Steinbuchel and Fuchtenbusch, 1998; Zinn et al., 2001; Suriyamongkol et al., 2007; Chanprateep, 2010; Keshavarz and Roy, 2010).

Chemically, PHAs are polyoxoesters of R‐hydroxyalkanoic acid monomers. They are usually classified depending on the number of carbon atoms of the alkyl groups: small chain length PHAs (scl‐PHAs) contain 3–5 carbon atoms [as poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate) ‐P(3HB)‐ or poly(4‐hydroxybutyrate) ‐P(4HB)], whereas medium chain length PHAs (mcl‐PHAs) possess 6–14 carbon atoms [e.g. poly(3‐hydroxyhexanoate), ‐P(3HHx) or poly(3‐hydroxyoctanoate) – P(3HO)]. Long‐chain‐length PHAs (lcl‐PHAs) consisting of hydroxyacids with more than 14 carbon atoms are more scarcely found (Rutherford et al., 1995; Singh and Mallick, 2009). These differences are mainly due to the substrate specificity of the PHA synthases from the particular microorganism (Park et al., 2012). Moreover, the incorporation of different monomer units in the same chain gives rise to heteropolymers with new properties. The properties and functionalities of the PHAs depend on their monomer composition: whereas scl‐PHAs show thermoplastic properties similar to polypropylene, mcl‐PHAs display elastic features similar to rubber or elastomer (Keshavarz and Roy, 2010; Park et al., 2012). Applications of PHAs in the industry are widespread, ranging from the manufacturing of packages and covers to the generation of enantiomeric pure chemicals (Philip et al., 2007) or as protein immobilization supports (Draper and Rehm, 2012; Dinjaski and Prieto, 2015; Hay et al., 2015). Of significant relevance is the implementation of PHAs in the biomedical discipline, especially supported by the recent FDA approval for P(4HB) to be used as suture material (Tepha Inc., MA, USA). The utility of PHAs in this field arises from their biocompatibility characteristics and has found its application in a variety of processes such as drug delivery, development of medical devices and construction of tissue engineering scaffolds (Misra et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2010; Xiong et al., 2010; Brigham and Sinskey, 2012; Martinez‐Donato et al., 2016; Rubio Reyes et al., 2016).

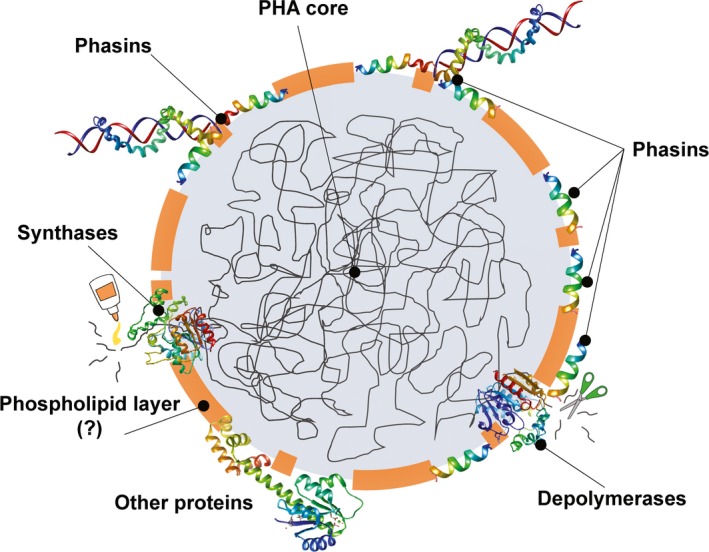

The PHA polymer accumulates in the cytoplasm in the form of water‐insoluble granules (Fig. 1), the number per cell and size of which depend on the different species and the culture conditions (Jendrossek and Pfeiffer, 2014). Early studies carried out by Merrick′s group showed that these inclusions were constituted by approximately 98% (w/w) PHA, 2% granule‐associated proteins (GAPs) and 0.5% phospholipids (Griebel et al., 1968). Since then, several studies have confirmed the presence of a phospholipid layer in PHA preparations (Parlane et al., 2016, and references therein). However, some data have put into question the actual presence of the lipid coat in vivo (Potter and Steinbuchel, 2006; Beeby et al., 2012; Jendrossek and Pfeiffer, 2014), especially from electron cryotomography (Wahl et al., 2012) and fluorescence microscopy (Bresan et al., 2016) results, according to which the presence of the lipid layer might arise from an experimental artefact on PHA extraction and preparation.

Figure 1.

Scheme of the structure of PHA granules.

Four different types of GAPs have been identified so far, namely PHA synthases, PHA depolymerases, phasins and other proteins (Steinbuchel et al., 1995), the latter including transcriptional regulators as well as hydrolases, reductases and other enzymes involved in the synthesis of PHA monomers (Jendrossek and Pfeiffer, 2014; Sznajder et al., 2015). Among them, phasins, which received their name in analogy to oleosins [proteins on the surface of oil globules found in oleaceous plants (Steinbuchel et al., 1995)], are the most abundant polypeptides in the PHA carbonosome (Mayer et al., 1996). These low molecular weight proteins normally contain a hydrophobic domain, associated with the PHA, and a hydrophilic/amphiphilic domain exposed to the cytoplasm (Potter and Steinbuchel, 2005). On the basis of their sequence, phasins are distributed in four families according to the Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org/), namely PF05597, PF09602, PF09650 and PF09361. A recent survey showed that a high percentage of phasins and phasin‐like proteins contains a leucine‐zipper motif in their amino acid sequences, suggesting that oligomerization is a common organization mechanism in these polypeptides (Maestro et al., 2013). In the recent years, a large number of phasins have been identified, constituting a phylogenetically heterogeneous group of proteins. We will review the current knowledge on the most representative phasins participating in important biological functions (summarized in Table 1) such as the formation of network‐like covers on the PHA granule surface (Dennis et al., 2003, 2008; Pfeiffer and Jendrossek, 2011) or the regulation of the synthesis, morphology, distribution during cell division and degradation of the storage granules (Mezzina and Pettinari, 2016). Finally, the biotechnological potential of this group of proteins will be discussed.

Table 1.

List of the phasins reviewed in the text, with their most relevant characteristics

| Organism | Phasin | Molecular mass (kDa) | UNIPROT accession number (localization) | Most relevant characteristics and roles | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ralstonia eutropha | PhaP1 Reu | 20.0 |

AAC78327 (chromosome 1) |

Homotrimer . Major phasin present in R. eutropha Plays role in the amount, size and number of granules, and in their degradation . Biotechnological application as immobilization tag |

(Steinbuchel et al., 1995; Wieczorek et al., 1995; York et al., 2001a; York et al., 2001b; Potter et al., 2002; York et al., 2002; Potter et al., 2004; Banki et al., 2005; Barnard et al., 2005; Backstrom et al., 2007; Kuchta et al., 2007; Neumann et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2008; Yao et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2014; Sznajder et al., 2015) |

| PhaP2 Reu | 20.2 |

AAP85954 (plasmid pHG1) |

Secondary participation in PHB accumulation and mobilization | (Schwartz et al., 2003; Potter et al., 2004) | |

| PhaP3 Reu | 19.6 |

AY489113 (chromosome 1) |

Secondary participation in PHB accumulation and mobilization | (Potter et al., 2004) | |

| PhaP4 Reu | 20.2 |

AY489114 (chromosome 2) |

Secondary participation in PHB accumulation and mobilization | (Potter et al., 2004) | |

| PhaP5Reu | 15.7 |

H16_B1934 (chromosome 2) |

Secondary participation in PHB accumulation and mobilization | (Pfeiffer and Jendrossek, 2011) | |

| PhaP6 Reu | 22.7 |

H16_B1988 (chromosome 2) |

Secondary participation in PHB accumulation and mobilization | (Pfeiffer and Jendrossek, 2012) | |

| PhaP7 Reu | 16.4 |

H16_B2326 (chromosome 2) |

Secondary participation in PHB accumulation and mobilization | (Pfeiffer and Jendrossek, 2012) | |

| Pseudomonas putida | PhaF | 26.3 | Q9Z5E6 |

Tetramer. Responsible for non‐specific binding to DNA . Intrinsically disordered in its majority unless bound to its ligands . Involved in the PHA biosynthesis, localization of the granules in the cell and in their distribution between daughter cells during cell division . Transcriptional regulator |

(Prieto et al., 1999; Moldes et al., 2004; Ren et al., 2010; Galan et al., 2011; Dinjaski and Prieto, 2013; Maestro et al., 2013) |

| PhaI | 15.4 | Q9Z5E7 |

Involved in the biosynthesis and accumulation of PHA . Biotechnological application as BioF affinity tag to immobilize or purify fusion proteins |

(Prieto et al., 1999; Moldes et al., 2004; Moldes et al., 2006; Ren et al., 2010; Dinjaski and Prieto, 2013; Maestro et al., 2013) | |

| Pseudomonas sp. 61‐3 | PhaF | 25.6 | Q8L3N9 | Phasin bound to P(3HB‐co‐3HA) copolymers solely when granules are enriched in 3HA (C6–C12) in more than 13 mol% | (Matsumoto et al., 2002 ; Hokamura et al., 2015) |

| PhaI | 15.4 | Q8L3P0 | Phasin bound to P(3HB‐co‐3HA) copolymers solely when granules are enriched in 3HA (C6–C12) in more than 13 mol% | (Matsumoto et al., 2002 ; Hokamura et al., 2015) | |

| PhbP | 20.4 | A0A0K2QTP6 | Phasin bound to P(3HB‐co‐3HA) copolymers solely when granules are enriched in 3HB in more than 87 mol% | (Matsumoto et al., 2002 ; Hokamura et al., 2015) | |

| Paracoccus denitrificans | PhaPPde | 16.5 | Q9WX81 | Involved in the PHA granule formation, ensuring the correct number and size of granules by preventing coalescence and their distribution throughout the cytoplasm | (Maehara et al., 1999) |

| Rhodococcus ruber | GA14 | 14.2 |

Q53051 (ORF3) |

Binding to the PHA through two hydrophobic patches present in the C‐terminal region of the protein Control of the granule size |

(Pieper and Steinbuchel, 1992; Pieper‐Furst et al., 1994; Pieper‐Furst et al., 1995) |

| Azotobacter sp. FA‐8 | PhaPAz | 20.4 | Q8KRE9 |

Tetramer. PHA binding by amphipathic α‐helices induces protein structuration. Promotes bacterial growth and PHA synthesis. General stress‐reducting action. Chaperone‐like mechanism |

(Pettinari et al., 2003; de Almeida et al., 2007; de Almeida et al., 2011; Mezzina et al., 2014; Mezzina et al., 2015) |

| Aeromonas caviae | PhaPAc | 12.6 | Q79EN2 | Important role in biosynthesis and metabolism of PHA | (Fukui et al., 2001; Saika et al., 2014; Ushimaru et al., 2014; Kawashima et al., 2015; Ushimaru et al., 2015) |

| Aeromonas hydrophila | PhaPAh | 12.6 | O32470 |

Tetrameric in solution, monomeric when bound to PHA granules. Involved in PHA biosynthesis. Controls granule size and number. Transcription regulator of phaC gene |

(Tian et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2016) |

| Rhodospirillum rubrum | ApdA | 17.5 | Q8GD50 | 55% identity with Mms16 from Magnetospirillum | (Handrick et al., 2004a; Handrick et al., 2004b) |

| Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens | PhaP1Bd | 12.3 | Q89JW4 | Predominantly alpha‐helical | (Yoshida et al., 2013; Quelas et al., 2016) |

| PhaP2Bd | 17.3 | Q89IS9 | Predominantly alpha‐helical | (Yoshida et al., 2013; Quelas et al., 2016) | |

| PhaP3Bd | 12.4 | Q89H66 |

Predominantly alpha‐helical. Minor expression |

(Yoshida et al., 2013; Quelas et al., 2016) | |

| PhaP4Bd | 15.4 | Q89DP4 |

Predominantly alpha‐helical. C‐terminal region very rich in alanine residues. Favoured expressed when using yeast extract‐mannitol medium |

(Yoshida et al., 2013; Quelas et al., 2016) |

Phasins from Ralstonia eutropha

Ralstonia eutropha (formerly Alcaligenes eutrophus, and also currently known as Cupriavidus necator H16) (Yabuuchi et al., 1995) is a Gram‐negative bacterium that produces scl‐PHA and represents the model organism in which biosynthesis and accumulation of poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate) [poly(3HB) or PHB in short], the most commercially successful PHA, has been more thoroughly studied (Sudesh et al., 2000; Steinbuchel and Hein, 2001; Stubbe et al., 2005; Potter and Steinbuchel, 2006). Ralstonia eutropha synthesizes PHB from acetyl‐CoA, catalysed by a β‐ketothiolase (PhaA), an acetoacetyl‐CoA reductase (PhaB) and the key enzyme PHA synthase (PhaC), all three proteins encoded by the phaCAB operon (Oeding and Schlegel, 1973; Haywood et al., 1988; Schubert et al., 1988; Slater et al., 1988; Peoples and Sinskey, 1989). The final PHB granules may represent up to 85% of the cell biomass (Vandamme and Coenye, 2004) and are coated with up to seven types of phasins (Potter et al., 2004; Pfeiffer and Jendrossek, 2012). Among these, PhaP1Reu is the most abundant one (Sznajder et al., 2015) covering an estimated 27–54% of surface of the PHA granules (Tian et al., 2005a), and representing around 5% of the total cell protein fraction (Wieczorek et al., 1995). PhaP1Reu is only synthesized in PHA‐producing cells in levels correlating well with the PHA accumulation, and it is never found in soluble form but only attached to the granules (Wieczorek et al., 1995; York et al., 2001a,b, 2002; Tian et al., 2005a). Besides PhaP1Reu, six additional and minoritaire phasins have also been identified in R. eutropha (PhaP2Reu‐PhaP7Reu). Phasins PhaP2Reu‐PhaP4Reu are homologous to PhaP1 and are only synthesized under permissive conditions for PHB accumulation, although in much lower amounts (Potter et al., 2004; Pfeiffer and Jendrossek, 2012). On the other hand, the PhaP5Reu‐PhaP7Reu proteins are not homologous to PhaP1Reu and probably represent an independent subgroup of phasin‐like proteins. Despite much effort dedicated to this task, the elucidation of the exact role of R. eutropha phasins other than PhaP1Reu in PHB homoeostasis remains elusive (Pfeiffer and Jendrossek, 2011, 2012).

Regarding the major phasin PhaP1Reu, this polypeptide appears strongly bound to the hydrophobic surface of the PHB polymer as soon as its accumulation starts (York et al., 2001b; Cho et al., 2012), ensuring the dispersion of the granules and preventing the non‐specific binding of other proteins. PhaP1Reu plays a crucial role in the amount (York et al., 2001a,b), size and number of granules (Steinbuchel et al., 1995; Wieczorek et al., 1995; Kuchta et al., 2007) and probably prevents PHB crystallization (Horowitz and Sanders, 1994). It has been demonstrated that PhaP1Reu deletion mutants exhibit less PHB production as compared to the wild‐type strain (Wieczorek et al., 1995; York et al., 2001b; Kuchta et al., 2007), indicating that it is important but not crucial for PHB synthesis, and suggesting that other minor phasins may also contribute to its accumulation. In fact, the expression level of PhaP3Reu significantly increases in PhaP1‐negative mutants (Potter et al., 2004). Nevertheless, in the presence of PhaP1 the relative importance of the other phasins must be lower, as the individual deletion of any of them does not induce any appreciable effect on polymer synthesis (Kuchta et al., 2007). Moreover, PhaP1Reu deletion mutants only produce a large, single granule per cell unlike wild‐type cells, which usually contain between 6 and 15 disperse, medium‐size granules (Wieczorek et al., 1995; Kuchta et al., 2007). In contrast, PhaP1Reu overexpression leads to the generation of a high number of small granules (Potter et al., 2002).

Ralstonia eutropha phasins also play a role in the stability and mobilization of PHB inclusions. Lack of PhaP1Reu in a single deletion mutant causes a certain degree of PHB autodegradation in vivo, an event that is dramatically augmented when combined with the multiple deletion of other phasins (Kuchta et al., 2007), suggesting that phasins are essential to stabilize the granule. Paradoxically, phasins are also critical for the mobilization of PHB induced by CoA thiolysis as catalysed by the PhaZ depolymerase. While PHB devoid of phasins is unable to be degraded by PhaZ, PhaP1Reu alone is sufficient to assist the depolymerase in PHB degradation (Uchino et al., 2007; Eggers and Steinbuchel, 2013). On the other hand, in the absence of PhaP1Reu, the other minor phasins may also participate in PHB mobilization to a variable extent (Kuchta et al., 2007; Uchino et al., 2007; Eggers and Steinbuchel, 2013).

Expression of PhaP1Reu is strictly regulated at the transcription level by PhaR (Potter et al., 2002; York et al., 2002), thus ensuring that the phasin is produced only when conditions are permissive for PHB accumulation and PhaC is present (York et al., 2001a), and in enough quantity to cover all the biopolymer surface, but without inducing a protein stock in the cytoplasm (Wieczorek et al., 1995).

It has been proposed that PhaP1Reu possesses a modulatory action on PHB synthesis in vitro on a PhaC‐dependent manner. Addition of pure recombinant PhaP1Reu increases the lag phase in the polymer formation for the R. eutropha PhaC1 synthase (Cho et al., 2012). A two‐hybrid assay did not detect any interaction between the two proteins (Pfeiffer and Jendrossek, 2011). A similar decrease in activity has also been detected for the synthase from Delftia acidovorans (PhaCDa) (Ushimaru et al., 2014) although no mechanism was proposed in this case. On the contrary, PhaP1Reu increases the activity of the synthases from Aeromonas caviae (Ushimaru et al., 2014) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Qi et al., 2000), this time by reducing the enzymatic lag phase, while it does not affect the activity of PhaC from Chromatium vinosum (Jossek et al., 1998).

Secondary structure analysis of the PhaP1Reu sequence predicts a highly α‐helical conformation that is characteristic of phasins (Neumann et al., 2008). The phasin has been shown to acquire a planar, triangular‐shaped homotrimeric conformation as revealed by small‐angle X‐ray scattering analysis (Neumann et al., 2008). First sequence analyses did not unveil a clear, predicted PHA‐binding motif such as long hydrophobic patches (Neumann et al., 2008).

Pseudomonas species

Most members of the Pseudomonas species are able to accumulate only mcl‐PHA granules based on a well‐conserved gene cluster containing two operons that are transcribed in opposite direction: (i) the phaC1ZC2D operon, encoding two type‐II polymerases (PhaC1 and PhaC2), a depolymerase (PhaZ) and the PhaD protein described as a putative transcriptional regulator (Huisman et al., 1991; Klinke et al., 2000; Steinbuchel and Hein, 2001); and (ii) the phaFI operon, located downstream and coding for the PhaF and PhaI phasins (Prieto et al., 1999; Sandoval et al., 2007).

The mcl‐PHA granules in Pseudomonas are covered by a protein layer that contains the PhaF and PhaI phasins, together with PhaC, PhaZ and the acyl‐CoA synthetase ACS1 (Prieto et al., 1999; Moldes et al., 2004; Peters and Rehm, 2005; de Eugenio et al., 2007; Sandoval et al., 2007; Ruth et al., 2008).

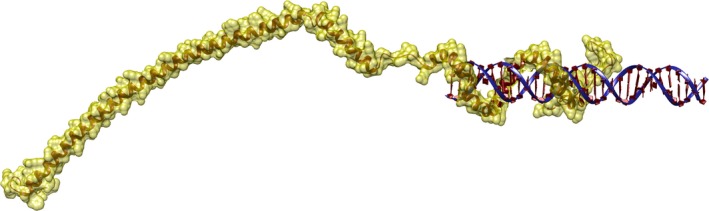

PhaF is the major phasin in Pseudomonas species, and it is structurally organized in two well‐defined domains (Prieto et al., 1999; Moldes et al., 2004), (i) the N‐terminal, PHA‐binding domain, (referred to as BioF in the case of P. putida GPo1), which shares sequence similarity with PhaI, and (ii) the C‐terminal moiety, a highly positively charged, histone‐like domain, containing eight AAKP‐like tandem repeats, and responsible for non‐specific binding to DNA (Prieto et al., 1999; Moldes et al., 2004; Galan et al., 2011). Biophysical studies carried out on PhaF, supported by a three‐dimensional structural model, suggest an elongated disposition in which the PHA‐binding domain acquires an amphipathic helix conformation suitable to recognize the surface of the polymer granule and that is separated from the DNA‐binding domain by a short leucine zipper presumably involved in the protein tetramerization (Maestro et al., 2013) (Fig. 2). Remarkably, similar coiled‐coil sequences were found in the majority of phasins included in the UniProtKB database, suggesting that oligomerization might constitute a common feature of these proteins (Maestro et al., 2013). Moreover, the protein might be intrinsically disordered in its majority unless bound to its ligands (PHA and DNA), a trait that is also probably shared by many other phasins (Maestro et al., 2013).

Figure 2.

Predicted structure of a monomer of the PhaF phasin from Pseudomonas putida KT2440 complexed to DNA (Maestro et al., 2013).

The functionality of PhaF is not only ascribed to a mere role in PHA intracellular stabilization, but it also plays a critical role in the localization of the granule in the cell centre, ensuring an equal distribution between daughter cells during cell division by a simultaneous attachment to the PHA polymer and to nucleoid DNA (Galan et al., 2011; Maestro et al., 2013). In this sense, lack of PhaF induces in vivo a considerable reduction in total PHA content as the defects caused in granule segregation gives rise to population heterogeneity (Galan et al., 2011; Dinjaski and Prieto, 2013). Interestingly, a similar function has been detected for the PhaM protein in R. eutropha, a phasin‐like polypeptide responsible for attachment of PHB granules to the bacterial nucleoid, ensuring an almost equal number of PHB granules to that both daughter cells after cell division (Pfeiffer et al., 2011; Wahl et al., 2012). Finally, it has been demonstrated that PhaF is also involved in the in the control of expression of the phaC1 synthase and phaI phasin genes (Prieto et al., 1999; Galan et al., 2011).

The PhaI phasin displays a high sequence similarity with the PHA‐binding domain of PhaF, including the probable Leu‐zipper sequence. Together with PhaF, it has been demonstrated to be essential for optimal PHA biosynthesis and accumulation in P. putida KT2442 and P. putida U (Ren et al., 2010; Dinjaski and Prieto, 2013) although it can be replaced by the homologous PHA‐binding domain of PhaF (Dinjaski and Prieto, 2013).

While most Pseudomonas spp accumulate only mcl‐PHA, some strains such as Pseudomonas sp.61‐3, Pseudomonas sp14‐3 and P. pseudoalcaligenes are also able to accumulate scl‐PHA such as PHB. In these cases, an additional phb cluster has been identified, containing genes coding for the proteins PHB synthase (PhbC), β‐ketothiolase (PhbA), NADPH‐dependent acetoacetyl coenzyme A reductase (PhbB) and the PhbP phasin involved in scl‐PHA metabolism (Matsusaki et al., 1998; Ayub et al., 2007; Manso Cobos et al., 2015). Interestingly, in Pseudomonas sp.61‐3 it has been demonstrated a certain degree of PHA specificity by the phasins, as PhaF and PhaI appear bound to P(3HB‐co‐3HA) copolymers only when the 3HA (C6–C12) composition is present in more than 13 mol %, whereas PhbP is solely found in 3HB enriched granules in more than 87 mol% (Hokamura et al., 2015).

Paracoccus denitrificans

Paracoccus denitrificans is a facultative methylotrophic bacterium capable of synthesizing scl‐PHAs from several alcohols (Yamane et al., 1996). The major phasin associated with PHA granules in P. denitrificans is PhaPPde (GA‐16) (Maehara et al., 1999). The expression of the phaP gene is negatively controlled by the auto‐regulated repressor PhaR (Maehara et al., 2002), and a positive correlation between the accumulation of PhaPPde protein and production of PHA has been demonstrated (Maehara et al., 1999). PhaPPde plays a structural role in the PHA granule formation, constituting an amphipathic layer, preventing the coalescence of the granules and ensuring the correct number and size of granules. Besides, it is also involved in the distribution of the granules throughout the cytoplasm (Maehara et al., 1999).

Rhodococcus ruber

The coryneform bacterium Rhodococcus ruber NCIMB 40126 accumulates a copolyester of 3‐hydroxybutyric acid and 3‐hydroxyvaleric acid from single, unrelated carbon sources (Haywood et al., 1991). The GA14 protein has been identified as the major phasin bound to the surface of the PHA granules, showing a direct correlation between the amount of protein and the level of PHA synthesis in the cells (Pieper and Steinbuchel, 1992; Pieper‐Furst et al., 1994). The C‐terminal region of the protein, containing two hydrophobic patches, has been demonstrated as responsible for the granule anchoring (Pieper‐Furst et al., 1995). This protein has also been isolated from lipid inclusions in this bacterium (Kalscheuer et al., 2001).

Azotobacter genus

PhaPAz is the most abundant PHB granule‐associated protein observed in Azotobacter sp. FA‐8 (Pettinari et al., 2003; Mezzina et al., 2015). This protein displays a growth‐promoting effect, also enhancing the polymer production in recombinant PHB‐producing Escherichia coli (de Almeida et al., 2007, 2011). Moreover, it exerts a stress‐reduction action, both in PHB and non‐PHB synthesizing bacteria, decreasing the induction of heat shock‐related genes in E. coli (de Almeida et al., 2011) and promoting protein folding through a chaperone‐like mechanism, which suggests an in vivo general protective role of this phasin (Mezzina et al., 2015).

PhaPAz has been suggested to conform a coiled‐coil tetramer when it is not bound to any target. Secondary structure analysis predicts the existence of α‐helices and disordered regions, with two amphipathic helices probably responsible for protein‐protein or PHB interactions. Spectroscopical studies suggest that hydrophobic environments, such as those provided by PHB, can induce phasin structuration (Mezzina et al., 2014).

Aeromonas genus

Aeromonas caviae FA440 is a Gram‐negative bacterium isolated from soil that is capable of producing copolyesters consisting of scl‐ and mcl‐PHA from alkanoates or oils (Doi et al., 1995). This organism possesses a biotechnological potential as the films made of the random copolymer of (R)‐3‐hydroxybutyrate and (R)‐3‐hydroxyhexanoate [P(3HB‐co‐3HHx)] produced by this bacteria have demonstrated very good soft and flexible properties, and better biocompatibility when compared to a P(3HB) homo‐polymer, making them suitable for more practical applications (Doi et al., 1995; Yang et al., 2002). The PHA biosynthetic operon in A. caviae consists on phaP‐phaC‐phaJ genes, which encode the PHA granule‐associated protein phasin (PhaPAc) (Fukui et al., 2001), as well as the PhaCAc synthase (Fukui and Doi, 1997), and the R‐specific enoyl‐CoA hydratase (PhaJAc) (Fukui et al., 1998).

The PHA granules isolated from A. caviae are relatively simple in terms of its GAPs composition, as their protein cover only comprises the PHA synthase and the PhaPAc phasin (Fukui et al., 2001). PhaPAc (also referred to as GA13) is a 13‐kDa protein, which shows an appreciable similarity with the PhaP phasin from Acinetobacter sp. (Fukui et al., 2001). Moreover, no hydrophobic or amphiphilic regions are evident in the primary structure of this protein (Fukui et al., 2001).

PhaPAc plays an important role in the biosynthesis and metabolism of PHAs. A high level activity of PHA synthase has been documented when overexpression of phaCAc takes place together with phaPAc, and the PHA copolymer composition is enriched in the 3HHx fraction when compared to overexpression of phaCAc alone, although the substrate specificity of PhaCAc is not affected in this conditions (Fukui et al., 2001). Besides, in a recombinant strain of R. eutropha which is capable of synthesizing P(3HB‐co‐3HHx), the replacement of the PhaP1Reu phasin by PhaPAc resulted in an increase in 3HHx proportion in the copolymer (Kawashima et al., 2015). Moreover, the activity of PhaCAc synthase in vitro is activated by the presence of PhaPAc both in the prepolymerization and the polymer‐elongation states, and the in vivo P(3HB) accumulation in a recombinant E. coli strain expressing PhaPAc increased 2.3‐fold when compared with the corresponding PhaPAc‐free strain (Ushimaru et al., 2014). This effect is not due to a mere increase in the amount of soluble PhaCAc, but probably arises from the phasin assisting the withdrawal of the growing PHA polymer chain from PhaCAc (Ushimaru et al., 2014). In contrast, the prepolymerization activities of PhaCRe and PhaCDa synthases decrease by the presence of PhaPAc, whereas the activity of polymer‐elongating PhaCRe is not affected. Interestingly, the in vivo accumulation of P(3HB) increases 1.2‐fold in a recombinant E. coli strain when PhaPAc is expressed together with PhaCRe, compared to the phasin‐free strain. As the amount of PhaCRe in the soluble fraction increases approximately threefold by PhaPAc coexpression, this has led to postulate that this enhanced PHA accumulation could be attributed to a chaperone‐like role of PhaPAc in the folding of PhaCRe (Ushimaru et al., 2014). Finally, an enhancement in the in vivo PHA accumulation has been observed in E. coli harbouring the phaPCJ operon from A. caviae when a single nucleotide mutation is present in the phaPAc gene (PhaPAcD4N) (Saika et al., 2014). The mutation does not induce an increase in the activity of the PHA synthase, but a higher expression level of phaPAc gene was demonstrated, suggesting that this effect could be attributed to the enhanced expression of the whole phaPCJ operon (Ushimaru et al., 2015).

Another Aeromonas species, A. hydrophila 4AK4, is a Gram‐negative bacterium initially isolated from raw sewage samples that is able to accumulate 35–50 wt. % copolymer [P(3HB‐co‐3HHx)] (Lee et al., 2000) reaching 70 wt. % in a metabolic engineered strain (Qiu et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2011), so this microorganism has been used for the industrial‐scale production of this PHA (Chen et al., 2001). A pha operon similar to A. caviae has been found in this species (Qiu et al., 2006). The phasin produced by this microorganism (PhaPAh) is a 13‐kDa protein whose overexpression leads to a higher number and a decrease in size of P(3HB‐co‐3HHx) granules, as well as to an increase in phaCAh gene transcription and to an increment of 3HHx fraction on the P(3HB‐co‐3HHx) accumulated copolymer, concomitantly with a reduced molecular weight of the polyester (Tian et al., 2005b). The 3‐D structure of PhaPAh has been recently elucidated by X‐ray crystallography (Zhao et al., 2016). The protein folds in solution into a brick‐like tetramer built from the packing of four amphipathic α‐helical monomers through their corresponding hydrophobic faces. On the basis of several biophysical and mutational studies, it has been suggested that in the presence of hydrophobic entities such as PHB surfaces, the tetramer dissociates and individual monomers are able then to interact with the non‐polar compound (Zhao et al., 2016).

Rhodospirillum rubrum

Rhodospirillum rubrum is a Gram‐negative, phototrophic, purple, non‐sulfur bacterium with a huge metabolic flexibility that allows it to produce many different types of storage polyesters, such as PHB, the poly‐(3‐hydroxybutyrate‐co‐3‐hydroxyvalerate) [P(3HB‐co‐3HHx)] copolymer, or even more polymers including β‐hydroxyhexanoate or β‐hydroxyheptanoate monomers, depending on the carbon source (Brandl et al., 1989). This organism appears well suited for fermenting synthesis gas raw materials, making it especially attractive for the bioconversion of syngas feedstocks into [P(3HB‐co‐3HHx)] copolyester (Do et al., 2007; Revelles et al., 2016).

ApdA (activator of polymer degradation) is a 17.5‐kDa phasin that is bound to the PHB granules in vivo in R. rubrum (Handrick et al., 2004a). It is absolutely required for the efficient hydrolysis in vitro of the native PHB (nPHB) granules by the PhaZ1 depolymerase, a role that is not affected by several physical and chemical stresses, such as high temperatures, extreme pH's or 5 M guanidinium, but that can be mimicked by the pretreatment of the granules with trypsin or other proteases, although no protease activity has been found for this phasin (Handrick et al., 2004a,2004b). On the other hand, ApdA presents a 55% identity with Mms16, a magnetosome‐associated protein in Magnetospirillum that has also been shown, in turn, to act as a phasin‐like protein bound to the PHB granules produced by this bacteria (Handrick et al., 2004a; Schultheiss et al., 2005). In fact, it has been shown that Mms16 is able to functionally replace the activating role of ApdA in R. rubrum (Handrick et al., 2004a).

Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens

Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens is a Gram‐negative soil bacterium that accumulates a large amount of PHB, a process that competes with the fixation of atmospheric N2 in symbiosis with soybean plants (Romanov et al., 1980). Four phasins have been identified in PHA granules from B. diazoefficiens, namely PhaP1Bd‐PhaP4Bd (Yoshida et al., 2013). None of them are involved in the bacterial growth kinetics (Quelas et al., 2016), but they are all expressed in levels that correlate with the accumulated PHA (Yoshida et al., 2013). In any case, expression of PhaP4Bd is favoured when using yeast extract‐mannitol (YM) medium, and it presents the highest affinity to PHA granules in vitro (Yoshida et al., 2013). Transcription of phaP3 seems to be low and constant during growth, suggesting that this phasin does not have a relevant role in PHA metabolism (Yoshida et al., 2013). On the other hand, the study of single and double mutants has revealed that the combined role of PhaP1Bd and PhaP4Bd must be crucial in determining the number and size of the granules (Quelas et al., 2016).

Structurally, PhaP1Bd‐PhaP4Bd are predicted to be predominantly alpha‐helical but only PhaP4Bd contains additionally a C‐terminal region very rich in alanine residues (13 out of 34 amino acids) (Yoshida et al., 2013). Besides, they are all proposed to oligomerize (Quelas et al., 2016).

Other phasins

Several other phasin proteins have been identified in other organisms such as Sinorhizobium meliloti, Haloferax mediterranii or Herbaspirillum seropedicae, but there is little information about them other than their involvement in PHA accumulation (Wang et al., 2007; Cai et al., 2012; Tirapelle et al., 2013; Alves et al., 2016).

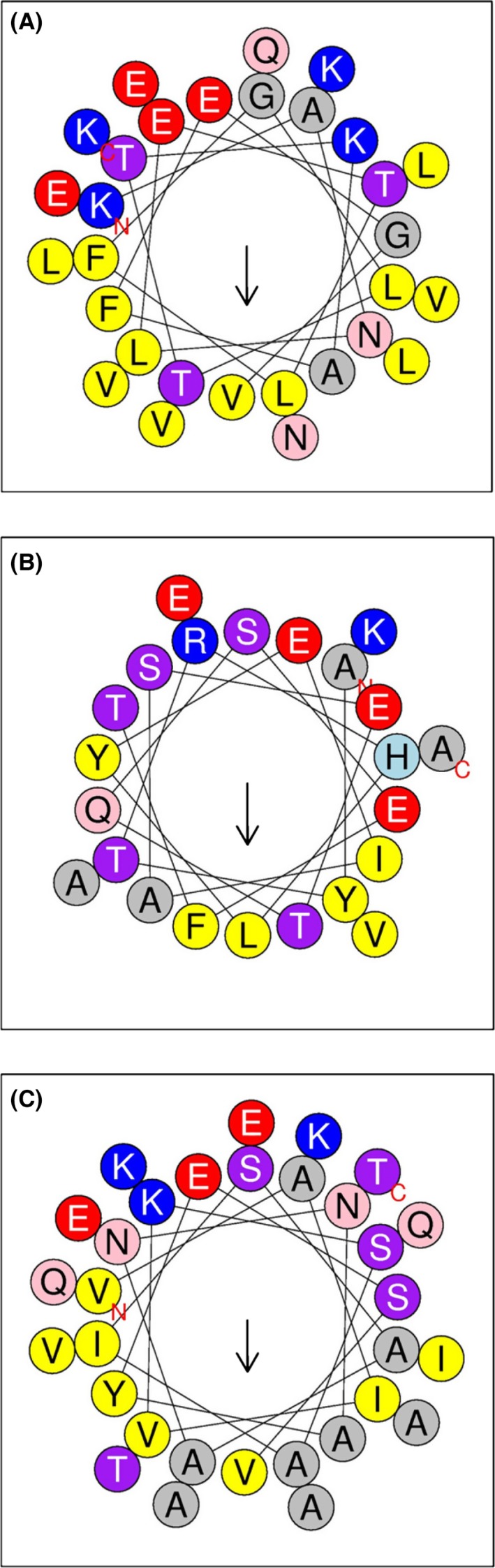

Binding of phasins to PHA

Little is known about the molecular details of phasin‐PHA interaction. In the absence of deeper biophysical analyses, some speculations can be made on the basis of the scarce protein structural data and secondary structure predictions. As described above, it has been suggested for the P. putida KT2442 PhaF phasin a non‐specific interaction through an amphipathic α‐helix, so that the hydrophobic side of the helix faces the polymer whereas the hydrophilic side is exposed to the solvent. Such statement is based on the fact that the granule‐binding sequence also interacts strongly with hydrophobic compounds (oleic acid) and chromatographic resins (phenyl‐sepharose) (Maestro et al., 2013). This idea receives considerable support after the elucidation of the PhaPAc three‐dimensional structure (Zhao et al., 2016), which confirms the widespread presence of amphipathic sequences along this protein. In addition, selected mutants of PhaPAc designed to increase the amphipathic character of the helices concomitantly led to a stronger binding to P(3HB‐co‐3HHx) films (Zhao et al., 2016). With the aim of checking whether this proposed mechanism might represent a common procedure used by phasins to interact with the PHB granule, we have carried out a theoretical study of secondary structure and amphipathicity prediction for each of the four Pfam phasin families. Due to the high number of phasin sequences to be analysed, we generated a consensus sequence for each family using the Jalview utility (Waterhouse et al., 2009). Then, a secondary structure prediction was carried out for each consensus sequence using Jpred4 (Drozdetskiy et al., 2015), and finally, all predicted α‐helical sequences were analysed for their amphipathicity with HeliQuest (Gautier et al., 2008). The results show phasins (belonging to the four Pfam families) as generally predicted, highly helical proteins with appreciable amphipathic stretches (See Fig. S1 and Fig. 3 for the specific case of PhaP1Reu from R. eutropha). This simple theoretical model, in the absence of more experimental confirmation, would explain some observations such as the lack of a defined PHA‐binding region in PhaP1Reu, as the PHA‐binding ability seems distributed throughout the protein (Neumann et al., 2008).

Figure 3.

HeliQuest prediction of amphipathic α‐helices in the sequence of PhaP1Reu from R. eutropha, belonging to Pfam family PF05597.

A. residues 13–42 (Mean hydrophobic moment ‐arrow‐) <μH> = 0.39);

B. residues 81–103 (<μH> = 0.40);

C. residues 131–161 (<μH> = 0.34). See Fig. S1 for details.

Biotechnological application of phasins

The amphiphilic character of phasins makes them suitable to be used as natural biosurfactants. In this sense, pure recombinant PhaPAh from A. hydrophila 4AK4 shows a strong effect to form emulsions with lubricating oil, diesel and soybean oil when compared with bovine serum albumin, sodium dodecylsulfate, Tween 20 or sodium oleate, even retaining its activity after heat‐treatment of the protein or the emulsions themselves (Wei et al., 2011).

In any case, the most widely studied application of phasins arises from their PHA‐binding capacity. In this regard, the N‐terminal, PHA‐binding domain of PhaF from Pseudomonas putida GPo1 (referred to as BioF sequence) has shown to be very effective as an affinity tag to immobilize in vivo fusion proteins using mcl‐PHA as support (Moldes et al., 2004, 2006). Polyester granules carrying BioF‐tagged fusion proteins can be easily isolated by centrifugation and used directly or, if required, the purification of the adsorbed protein can be achieved by gentle elution with detergents, keeping their full activity in both cases (Moldes et al., 2004). This system has been demonstrated to be an eco‐friendly way to deliver active proteins to the environment such as the Cry1Ab toxin with insecticidal activity (Moldes et al., 2006).

Similar in vivo immobilization procedures have also been developed for PhaP1Reu using E. coli as heterologous host for the PHA synthesis (Chen et al., 2014). In this case, the gene coding for the D‐hydantoinase (D‐HDT) (enzyme involved in the generation of D‐amino acids of commercial values such as one of the precursors required for the synthesis of semi‐synthetic antibiotics) was fused to phaP1. The recombinant fusion protein, PhaP1Reu‐HDT, resulted to be effectively attached to the granules, and the enzyme showed to be active and stable (Chen et al., 2014). In a further development, Wood′s group also used the PhaP1Reu phasin and E. coli or R. eutropha as expression and immobilization hosts, but in this case they incorporated a self‐cleaving intein sequence between the affinity tag and the protein of interest, allowing the easy removal of the tag and the subsequent purification of the native product by a simple pH change (Banki et al., 2005; Barnard et al., 2005). The advantage of these procedures comes from the fact that both protein and support are easily and effectively produced by the same bacterial host, leading to cost reduction in the downstream process. In any case, binding and purification can also be carried out in vitro, allowing protein production in a continuous way as demonstrated by Wang and coworkers for PhaPAc (Wang et al., 2008).

The specific immobilization of fusion proteins to PHA via phasins is starting to be employed in medicine, both in diagnostic and drug delivery applications. In the first case, two hybrid genes encoding either the mouse interleukin‐2 (IL2) or the myelinoligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) fused to PhaP1Reu were constructed and expressed in a recombinant, PHA‐accumulating E. coli strain. The PHA beads obtained from this system displayed the eukaryotic proteins correctly folded, and they were subsequently implemented for specific and sensitive antibody detection using the fluorescence‐activated cell sorting (FACS) technology (Backstrom et al., 2007). In another example, two recombinant fusion proteins with PhaP1Reu were generated to achieve specific delivery: mannosylated human α1‐acid glycoprotein (hAGP), that is able to bind to the mannose receptor of macrophages, and a human epidermal growth factor (hEGF), able to recognize EGF receptors on carcinoma cells. The resulting proteins (rhAGP–PhaP1Reu and rhEGF–PhaP1Reu) were self‐assembled on P(3HB‐co‐3HHx) nanoparticles, achieving the specific delivery of the payload both in vitro and in vivo (Yao et al., 2008). On the other hand, the sequence coding for a peptide containing the amino acids Arg‐Gly‐Asp, the most effective peptide sequence used to improve cell adhesion on artificial surfaces, was fused to PhaPAc (Dong et al., 2010). Different polyesters, such as P(3HB‐co‐3HHx) or P(3HB‐co‐3HV), were coated with purified PhaP‐RGD hybrid protein, and the complex proved effective in adhesion and improvement of cell growth on two different fibroblast cellular lines, suggesting viable applications on implant biomaterials (Dong et al., 2010).

Concluding remarks

The generic name of ‘phasin’ denotes a set of proteins which indeed share the ability to recognize and adsorb to PHA polyesters. They play an essential contribution in the physical stabilization of the PHA granule within the cell, ensure the correct distribution of the polyester upon cell division and assist other proteins (synthases and depolymerases) on PHA metabolism. Nevertheless, their specific role is highly dependent both on the microbial strain and on the metabolic state of the cell. Their versatility is such that they may even participate in opposite events (e.g. synthesis and degradation of the PHA polymer). Besides, their strong affinity to PHA allows their use as protein affinity tags for polymer functionalization and therefore constitutes an opportunity to develop valuable applications in biotechnology and biomedicine. Although little structural data are still available, phasins are predicted to acquire relatively simple, amphipathic, three‐dimensional structures and to bind to PHA via non‐specific hydrophobic interactions. This makes them amenable to be easily engineered to produce recombinant variants that display a modulated affinity to PHA, that may be useful both for in vivo PHA production and in vitro biotechnological and biomedical applications.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Supporting information

Fig. S1. (A–D). Secondary structure and amphipatic α‐helix predictions of consensus sequences derived from phasin‐related Pfam families (http://pfam.xfam.org/).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Auxi Prieto for her valuable comments on several aspects of this manuscript. This work was supported by grants BIO2013‐47684‐R and BIO2016‐79323‐R (Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness).

Microbial Biotechnology (2017) 10(6), 1323–1337

Contributor Information

Beatriz Maestro, Email: bmaestro35@gmail.com.

Jesús M. Sanz, Email: jmsanz@umh.es

References

- de Almeida, A. , Nikel, P.I. , Giordano, A.M. , and Pettinari, M.J. (2007) Effects of granule‐associated protein PhaP on glycerol‐dependent growth and polymer production in poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate)‐producing Escherichia coli . Appl Environ Microbiol 73: 7912–7916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida, A. , Catone, M.V. , Rhodius, V.A. , Gross, C.A. , and Pettinari, M.J. (2011) Unexpected stress‐reducing effect of PhaP, a poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate) granule‐associated protein, in Escherichia coli . Appl Environ Microbiol 77: 6622–6629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves, L.P. , Teixeira, C.S. , Tirapelle, E.F. , Donatti, L. , Tadra‐Sfeir, M.Z. , Steffens, M.B. , et al (2016) Backup expression of the PhaP2 phasin compensates for phaP1 deletion in Herbaspirillum seropedicae, maintaining fitness and PHB accumulation. Front Microbiol 7: 739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, A.J. , and Dawes, E.A. (1990) Occurrence, metabolism, metabolic role, and industrial uses of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates. Microbiol Rev 54: 450–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayub, N.D. , Pettinari, M.J. , Mendez, B.S. , and Lopez, N.I. (2007) The polyhydroxyalkanoate genes of a stress resistant Antarctic Pseudomonas are situated within a genomic island. Plasmid 58: 240–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backstrom, B.T. , Brockelbank, J.A. , and Rehm, B.H. (2007) Recombinant Escherichia coli produces tailor‐made biopolyester granules for applications in fluorescence activated cell sorting: functional display of the mouse interleukin‐2 and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. BMC Biotechnol 7: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banki, M.R. , Gerngross, T.U. , and Wood, D.W. (2005) Novel and economical purification of recombinant proteins: intein‐mediated protein purification using in vivo polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) matrix association. Protein Sci 14: 1387–1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, G.C. , McCool, J.D. , Wood, D.W. , and Gerngross, T.U. (2005) Integrated recombinant protein expression and purification platform based on Ralstonia eutropha . Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 5735–5742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeby, M. , Cho, M. , Stubbe, J. , and Jensen, G.J. (2012) Growth and localization of polyhydroxybutyrate granules in Ralstonia eutropha . J Bacteriol 194: 1092–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandl, H. , Knee, E.J. Jr , Fuller, R.C. , Gross, R.A. , and Lenz, R.W. (1989) Ability of the phototrophic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum to produce various poly (beta‐hydroxyalkanoates): potential sources for biodegradable polyesters. Int J Biol Macromol 11: 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresan, S. , Sznajder, A. , Hauf, W. , Forchhammer, K. , Pfeiffer, D. , and Jendrossek, D. (2016) Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) granules have no phospholipids. Sci Rep 6: 26612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigham, C.J. , and Sinskey, A.J. (2012) Applications of polyhydroxyalkanoates in the medical industry. Int J Biotechnol Wellness Ind 1: 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, S. , Cai, L. , Liu, H. , Liu, X. , Han, J. , Zhou, J. , and Xiang, H. (2012) Identification of the haloarchaeal phasin (PhaP) that functions in polyhydroxyalkanoate accumulation and granule formation in Haloferax mediterranei . Appl Environ Microbiol 78: 1946–1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanprateep, S. (2010) Current trends in biodegradable polyhydroxyalkanoates. J Biosci Bioeng 110: 621–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.Q. , Zhang, G. , Park, S.J. , and Lee, S.Y. (2001) Industrial scale production of poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate‐co‐3‐hydroxyhexanoate). Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 57: 50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.Y. , Chien, Y.W. , and Chao, Y.P. (2014) In vivo immobilization of D‐hydantoinase in Escherichia coli . J Biosci Bioeng 118: 78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho, M. , Brigham, C.J. , Sinskey, A.J. , and Stubbe, J. (2012) Purification of polyhydroxybutyrate synthase from its native organism, Ralstonia eutropha: implications for the initiation and elongation of polymer formation in vivo . Biochemistry 51: 2276–2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, D. , Liebig, C. , Holley, T. , Thomas, K.S. , Khosla, A. , Wilson, D. , and Augustine, B. (2003) Preliminary analysis of polyhydroxyalkanoate inclusions using atomic force microscopy. FEMS Microbiol Lett 226: 113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, D. , Sein, V. , Martinez, E. , and Augustine, B. (2008) PhaP is involved in the formation of a network on the surface of polyhydroxyalkanoate inclusions in Cupriavidus necator H16. J Bacteriol 190: 555–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinjaski, N. , and Prieto, M.A. (2013) Swapping of phasin modules to optimize the in vivo immobilization of proteins to medium‐chain‐length polyhydroxyalkanoate granules in Pseudomonas putida . Biomacromol 14: 3285–3293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinjaski, N. , and Prieto, M.A. (2015) Smart polyhydroxyalkanoate nanobeads by protein based functionalization. Nanomedicine 11: 885–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do, Y.S. , Smeenk, J. , Broer, K.M. , Kisting, C.J. , Brown, R. , Heindel, T.J. , et al (2007) Growth of Rhodospirillum rubrum on synthesis gas: conversion of CO to H2 and poly‐beta‐hydroxyalkanoate. Biotechnol Bioeng 97: 279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi, Y. , Kitamura, S. , and Abe, H. (1995) Microbial synthesis and characterization of Poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate‐co‐3‐hydroxyhexanoate). Macromolecules 28: 4822–4828. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y. , Li, P. , Chen, C.B. , Wang, Z.H. , Ma, P. , and Chen, G.Q. (2010) The improvement of fibroblast growth on hydrophobic biopolyesters by coating with polyhydroxyalkanoate granule binding protein PhaP fused with cell adhesion motif RGD. Biomaterials 31: 8921–8930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper, J.L. , and Rehm, B.H. (2012) Engineering bacteria to manufacture functionalized polyester beads. Bioengineered 3: 203–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drozdetskiy, A. , Cole, C. , Procter, J. , and Barton, G.J. (2015) JPred4: a protein secondary structure prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res 43: W389–W394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers, J. , and Steinbuchel, A. (2013) Poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate) degradation in Ralstonia eutropha H16 is mediated stereoselectively to (S)‐3‐hydroxybutyryl coenzyme A (CoA) via crotonyl‐CoA. J Bacteriol 195: 3213–3223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Eugenio, L.I. , Garcia, P. , Luengo, J.M. , Sanz, J.M. , Roman, J.S. , Garcia, J.L. , and Prieto, M.A. (2007) Biochemical evidence that phaZ gene encodes a specific intracellular medium chain length polyhydroxyalkanoate depolymerase in Pseudomonas putida KT2442: characterization of a paradigmatic enzyme. J Biol Chem 282: 4951–4962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui, T. , and Doi, Y. (1997) Cloning and analysis of the poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate‐co‐3‐hydroxyhexanoate) biosynthesis genes of Aeromonas caviae . J Bacteriol 179: 4821–4830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui, T. , Shiomi, N. , and Doi, Y. (1998) Expression and characterization of (R)‐specific enoyl coenzyme A hydratase involved in polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis by Aeromonas caviae . J Bacteriol 180: 667–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui, T. , Kichise, T. , Iwata, T. , and Doi, Y. (2001) Characterization of 13 kDa granule‐associated protein in Aeromonas caviae and biosynthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates with altered molar composition by recombinant bacteria. Biomacromol 2: 148–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galan, B. , Dinjaski, N. , Maestro, B. , de Eugenio, L.I. , Escapa, I.F. , Sanz, J.M. , et al (2011) Nucleoid‐associated PhaF phasin drives intracellular location and segregation of polyhydroxyalkanoate granules in Pseudomonas putida KT2442. Mol Microbiol 79: 402–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier, R. , Douguet, D. , Antonny, B. , and Drin, G. (2008) HELIQUEST: a web server to screen sequences with specific alpha‐helical properties. Bioinformatics 24: 2101–2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griebel, R. , Smith, Z. , and Merrick, J.M. (1968) Metabolism of poly‐beta‐hydroxybutyrate. I. Purification, composition, and properties of native poly‐beta‐hydroxybutyrate granules from Bacillus megaterium . Biochemistry 7: 3676–3681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handrick, R. , Reinhardt, S. , Schultheiss, D. , Reichart, T. , Schuler, D. , Jendrossek, V. , and Jendrossek, D. (2004a) Unraveling the function of the Rhodospirillum rubrum activator of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) degradation: the activator is a PHB‐granule‐bound protein (phasin). J Bacteriol 186: 2466–2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handrick, R. , Technow, U. , Reichart, T. , Reinhardt, S. , Sander, T. , and Jendrossek, D. (2004b) The activator of the Rhodospirillum rubrum PHB depolymerase is a polypeptide that is extremely resistant to high temperature (121 degrees C) and other physical or chemical stresses. FEMS Microbiol Lett 230: 265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay, I.D. , Du, J. , Reyes, P.R. , and Rehm, B.H. (2015) In vivo polyester immobilized sortase for tagless protein purification. Microb Cell Fact 14: 190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haywood, G.W. , Anderson, A.J. , Chu, L. , and Dawes, E.A. (1988) Characterization of two 3‐ketothiolases possessing differing substrate specificities in the polyhydroxyalkanoate synthesizing organism Alcaligenes eutrophus . FEMS Microbiol Lett 52: 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Haywood, G.W. , Anderson, A.J. , Williams, D.R. , Dawes, E.A. , and Ewing, D.F. (1991) Accumulation of a poly(hydroxyalkanoate) copolymer containing primarily 3‐hydroxyvalerate from simple carbohydrate substrates by Rhodococcus sp. NCIMB 40126. Int J Biol Macromol 13: 83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hokamura, A. , Fujino, K. , Isoda, Y. , Arizono, K. , Shiratsuchi, H. , and Matsusaki, H. (2015) Characterization and identification of the proteins bound to two types of polyhydroxyalkanoate granules in Pseudomonas sp. 61‐3. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 79: 1369–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, D.M. , and Sanders, J.K.M. (1994) Amorphous, biomimetic granules of polyhydroxybutyrate: preparation, characterization, and biological implications. J Am Chem Soc 116: 2695–2702. [Google Scholar]

- Huisman, G.W. , Wonink, E. , Meima, R. , Kazemier, B. , Terpstra, P. , and Witholt, B. (1991) Metabolism of poly(3‐hydroxyalkanoates) (PHAs) by Pseudomonas oleovorans. Identification and sequences of genes and function of the encoded proteins in the synthesis and degradation of PHA. J Biol Chem 266: 2191–2198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jendrossek, D. , and Pfeiffer, D. (2014) New insights in the formation of polyhydroxyalkanoate granules (carbonosomes) and novel functions of poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate). Environ Microbiol 16: 2357–2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jossek, R. , Reichelt, R. , and Steinbuchel, A. (1998) In vitro biosynthesis of poly(3‐hydroxybutyric acid) by using purified poly(hydroxyalkanoic acid) synthase of Chromatium vinosum . Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 49: 258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalscheuer, R. , Waltermann, M. , Alvarez, M. , and Steinbuchel, A. (2001) Preparative isolation of lipid inclusions from Rhodococcus opacus and Rhodococcus ruber and identification of granule‐associated proteins. Arch Microbiol 177: 20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima, Y. , Orita, I. , Nakamura, S. , and Fukui, T. (2015) Compositional regulation of poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate‐co‐3‐hydroxyhexanoate) by replacement of granule‐associated protein in Ralstonia eutropha. Microb Cell Fact 14: 187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarz, T. , and Roy, I. (2010) Polyhydroxyalkanoates: bioplastics with a green agenda. Curr Opin Microbiol 13: 321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinke, S. , de Roo, G. , Witholt, B. , and Kessler, B. (2000) Role of PhaD in accumulation of medium‐chain‐length Poly(3‐hydroxyalkanoates) in Pseudomonas oleovorans . Appl Environ Microbiol 66: 3705–3710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchta, K. , Chi, L. , Fuchs, H. , Potter, M. , and Steinbuchel, A. (2007) Studies on the influence of phasins on accumulation and degradation of PHB and nanostructure of PHB granules in Ralstonia eutropha H16. Biomacromol 8: 657–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.Y. (1996) Bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates. Biotechnol Bioeng 49: 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H. , Oh, D.H. , Ahn, W.S. , Lee, Y. , Choi, J. , and Lee, S.Y. (2000) Production of poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate‐co‐3‐hydroxyhexanoate) by high‐cell‐density cultivation of Aeromonas hydrophila . Biotechnol Bioeng 67: 240–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemoigne, M. (1926) Products of dehydration and of polymerization of beta‐hydroxybutyric acid. Bull Soc Chem Biol 8: 770–782. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F. , Jian, J. , Shen, X. , Chung, A. , Chen, J. , and Chen, G.Q. (2011) Metabolic engineering of Aeromonas hydrophila 4AK4 for production of copolymers of 3‐hydroxybutyrate and medium‐chain‐length 3‐hydroxyalkanoate. Bioresour Technol 102: 8123–8129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison, L.L. , and Huisman, G.W. (1999) Metabolic engineering of poly(3‐hydroxyalkanoates): from DNA to plastic. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 63: 21–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maehara, A. , Ueda, S. , Nakano, H. , and Yamane, T. (1999) Analyses of a polyhydroxyalkanoic acid granule‐associated 16‐kilodalton protein and its putative regulator in the pha locus of Paracoccus denitrificans . J Bacteriol 181: 2914–2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maehara, A. , Taguchi, S. , Nishiyama, T. , Yamane, T. , and Doi, Y. (2002) A repressor protein, PhaR, regulates polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) synthesis via its direct interaction with PHA. J Bacteriol 184: 3992–4002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestro, B. , Galan, B. , Alfonso, C. , Rivas, G. , Prieto, M.A. , and Sanz, J.M. (2013) A new family of intrinsically disordered proteins: structural characterization of the major phasin PhaF from Pseudomonas putida KT2440. PLoS ONE 8: e56904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manso Cobos, I. , Ibañez Garcia, M.I. , de la Pena Moreno, F. , Saez Melero, L.P. , Luque‐Almagro, V.M. , Castillo Rodriguez, F. , et al (2015) Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes CECT5344, a cyanide‐degrading bacterium with by‐product (polyhydroxyalkanoates) formation capacity. Microb Cell Fact 14: 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez‐Donato, G. , Piniella, B. , Aguilar, D. , Olivera, S. , Perez, A. , Castanedo, Y. , et al (2016) Protective T cell and antibody immune responses against hepatitis C virus achieved using a biopolyester‐bead‐based vaccine delivery system. Clin Vaccine Immunol 23: 370–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, K. , Matsusaki, H. , Taguchi, K. , Seki, M. , and Doi, Y. (2002). Isolation and characterization of polyhydroxyalkanoates inclusions and their associated proteins in Pseudomonas sp. 61–3. Biomacromolecules 3: 787–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsusaki, H. , Manji, S. , Taguchi, K. , Kato, M. , Fukui, T. , and Doi, Y. (1998) Cloning and molecular analysis of the Poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate) and Poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate‐co‐3‐hydroxyalkanoate) biosynthesis genes in Pseudomonas sp. strain 61‐3. J Bacteriol 180: 6459–6467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, F. , Madkour, M.H. , Pieper‐Fürst, U. , Wieczorek, R. , Liebergesell, M. , and Steinbüchel, A. (1996) Electron microscopic observations on the macromolecular organization of the boundary layer of bacterial PHA inclusion bodies. J Gen Appl Microbiol 42: 445–455. [Google Scholar]

- Mezzina, M.P. , and Pettinari, M.J. (2016) Phasins, multifaceted polyhydroxyalkanoate granule‐associated proteins. Appl Environ Microbiol 82: 5060–5067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzina, M.P. , Wetzler, D.E. , Catone, M.V. , Bucci, H. , Di Paola, M. , and Pettinari, M.J. (2014) A phasin with many faces: structural insights on PhaP from Azotobacter sp. FA8. PLoS ONE 9: e103012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzina, M.P. , Wetzler, D.E. , de Almeida, A. , Dinjaski, N. , Prieto, M.A. , and Pettinari, M.J. (2015) A phasin with extra talents: a polyhydroxyalkanoate granule‐associated protein has chaperone activity. Environ Microbiol 17: 1765–1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra, S.K. , Valappil, S.P. , Roy, I. , and Boccaccini, A.R. (2006) Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA)/inorganic phase composites for tissue engineering applications. Biomacromol 7: 2249–2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldes, C. , Garcia, P. , Garcia, J.L. , and Prieto, M.A. (2004) In vivo immobilization of fusion proteins on bioplastics by the novel tag BioF. Appl Environ Microbiol 70: 3205–3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldes, C. , Farinos, G.P. , de Eugenio, L.I. , Garcia, P. , Garcia, J.L. , Ortego, F. , et al (2006) New tool for spreading proteins to the environment: Cry1Ab toxin immobilized to bioplastics. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 72: 88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, L. , Spinozzi, F. , Sinibaldi, R. , Rustichelli, F. , Potter, M. , and Steinbuchel, A. (2008) Binding of the major phasin, PhaP1, from Ralstonia eutropha H16 to poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate) granules. J Bacteriol 190: 2911–2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oeding, V. , and Schlegel, H.G. (1973) Beta‐ketothiolase from Hydrogenomonas eutropha H16 and its significance in the regulation of poly‐beta‐hydroxybutyrate metabolism. Biochem J 134: 239–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.J. , Kim, T.W. , Kim, M.K. , Lee, S.Y. , and Lim, S.C. (2012) Advanced bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates: towards a versatile and sustainable platform for unnatural tailor‐made polyesters. Biotechnol Adv 30: 1196–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parlane, N.A. , Gupta, S.K. , Rubio Reyes, P. , Chen, S. , Gonzalez‐Miro, M. , Wedlock, D.N. and Rehm, B.H. (2016) Self‐assembled protein‐coated polyhydroxyalkanoate beads: properties and biomedical applications. ACS Biomater Sci Eng [In press]. DOI: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.6b00355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peoples, O.P. and Sinskey, A.J. (1989) Poly‐beta‐hydroxybutyrate (PHB) biosynthesis in Alcaligenes eutrophus H16. Identification and characterization of the PHB polymerase gene (phbC). J Biol Chem 264, 15298–15303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, V. , and Rehm, B.H. (2005) In vivo monitoring of PHA granule formation using GFP‐labeled PHA synthases. FEMS Microbiol Lett 248: 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettinari, J.M. , Chaneton, L. , Vazquez, G. , Steinbuchel, A. , and Mendez, B.S. (2003) Insertion sequence‐like elements associated with putative polyhydroxybutyrate regulatory genes in Azotobacter sp. FA8. Plasmid 50: 36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, D. , and Jendrossek, D. (2011) Interaction between poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate) granule‐associated proteins as revealed by two‐hybrid analysis and identification of a new phasin in Ralstonia eutropha H16. Microbiology 157: 2795–2807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, D. , and Jendrossek, D. (2012) Localization of poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) granule‐associated proteins during PHB granule formation and identification of two new phasins, PhaP6 and PhaP7, in Ralstonia eutropha H16. J Bacteriol 194: 5909–5921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, D. , Wahl, A. , and Jendrossek, D. (2011) Identification of a multifunctional protein, PhaM, that determines number, surface to volume ratio, subcellular localization and distribution to daughter cells of poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate), PHB, granules in Ralstonia eutropha H16. Mol Microbiol 82: 936–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip, S. , Keshavarz, T. , and Roy, I. (2007) Polyhydroxyalkanoates: biodegradable polymers with a range of applications. J Chem Technol Biotechnol 82: 233–247. [Google Scholar]

- Pieper, U. , and Steinbuchel, A. (1992) Identification, cloning and sequence analysis of the poly(3‐hydroxyalkanoic acid) synthase gene of the gram‐positive bacterium Rhodococcus ruber . FEMS Microbiol Lett 75: 73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieper‐Furst, U. , Madkour, M.H. , Mayer, F. , and Steinbuchel, A. (1994) Purification and characterization of a 14‐kilodalton protein that is bound to the surface of polyhydroxyalkanoic acid granules in Rhodococcus ruber . J Bacteriol 176: 4328–4337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieper‐Furst, U. , Madkour, M.H. , Mayer, F. , and Steinbuchel, A. (1995) Identification of the region of a 14‐kilodalton protein of Rhodococcus ruber that is responsible for the binding of this phasin to polyhydroxyalkanoic acid granules. J Bacteriol 177: 2513–2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter, M. , and Steinbuchel, A. (2005) Poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate) granule‐associated proteins: impacts on poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate) synthesis and degradation. Biomacromol 6: 552–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter, M. , and Steinbuchel, A. (2006) Biogenesis and Structure of Polyhydroxyalkanoate Granules. Berlin: Springer Verlag, pp. 109–136. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, M. , Madkour, M.H. , Mayer, F. , and Steinbuchel, A. (2002) Regulation of phasin expression and polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) granule formation in Ralstonia eutropha H16. Microbiology 148: 2413–2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter, M. , Muller, H. , Reinecke, F. , Wieczorek, R. , Fricke, F. , Bowien, B. , et al (2004) The complex structure of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) granules: four orthologous and paralogous phasins occur in Ralstonia eutropha . Microbiology 150: 2301–2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto, M.A. , Buhler, B. , Jung, K. , Witholt, B. , and Kessler, B. (1999) PhaF, a polyhydroxyalkanoate‐granule‐associated protein of Pseudomonas oleovorans GPo1 involved in the regulatory expression system for pha genes. J Bacteriol 181: 858–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Q. , Steinbuchel, A. , and Rehm, B.H. (2000) In vitro synthesis of poly(3‐hydroxydecanoate): purification and enzymatic characterization of type II polyhydroxyalkanoate synthases PhaC1 and PhaC2 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 54: 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Y.Z. , Han, J. , and Chen, G.Q. (2006) Metabolic engineering of Aeromonas hydrophila for the enhanced production of poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate‐co‐3‐hydroxyhexanoate). Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 69: 537–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quelas, J.I. , Mesa, S. , Mongiardini, E.J. , Jendrossek, D. , and Lodeiro, A.R. (2016) Regulation of polyhydroxybutyrate synthesis in the soil bacterium Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens . Appl Environ Microbiol 82: 4299–4308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Q. , de Roo, G. , Witholt, B. , Zinn, M. , and Thony‐Meyer, L. (2010) Influence of growth stage on activities of polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) polymerase and PHA depolymerase in Pseudomonas putida U. BMC Microbiol 10: 254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revelles, O. , Beneroso, D. , Menendez, J.A. , Arenillas, A. , Garcia, J.L. and Prieto, M.A. (2016) Syngas obtained by microwave pyrolysis of household wastes as feedstock for polyhydroxyalkanoate production in Rhodospirillum rubrum . Microb Biotechnol . [In press]. DOI:10.1111/1751‐7915.12411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanov, V.I. , Fedulova, N.G. , Tchermenskaya, I.E. , Shramko, V.I. , Molchanov, M.I. , and Kretovich, W.L. (1980) Metabolism of poly‐β‐hydroxybutyric acid in bacteroids of Rhizobium lupini in connection with nitrogen fixation and photosynthesis. Plant Soil 56: 379–390. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio Reyes, P. , Parlane, N.A. , Wedlock, D.N. , and Rehm, B.H. (2016) Immunogencity of antigens from Mycobacterium tuberculosis self‐assembled as particulate vaccines. Int J Med Microbiol 306: 624–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruth, K. , de Roo, G. , Egli, T. , and Ren, Q. (2008) Identification of two acyl‐CoA synthetases from Pseudomonas putida GPo1: one is located at the surface of polyhydroxyalkanoates granules. Biomacromol 9: 1652–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford, D.R. , Hammar, W.J. and Gaddam, B.N. (1995) Poly(beta‐hydroxyorganoate) pressure sensitive adhesive compositions. Patent EP0775178. Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company.

- Saika, A. , Watanabe, Y. , Sudesh, K. , and Tsuge, T. (2014) Biosynthesis of poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate‐co‐3‐hydroxy‐4‐methylvalerate) by recombinant Escherichia coli expressing leucine metabolism‐related enzymes derived from Clostridium difficile . J Biosci Bioeng 117: 670–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval, A. , Arias‐Barrau, E. , Arcos, M. , Naharro, G. , Olivera, E.R. , and Luengo, J.M. (2007) Genetic and ultrastructural analysis of different mutants of Pseudomonas putida affected in the poly‐3‐hydroxy‐n‐alkanoate gene cluster. Environ Microbiol 9: 737–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, P. , Steinbuchel, A. , and Schlegel, H.G. (1988) Cloning of the Alcaligenes eutrophus genes for synthesis of poly‐beta‐hydroxybutyric acid (PHB) and synthesis of PHB in Escherichia coli . J Bacteriol 170: 5837–5847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultheiss, D. , Handrick, R. , Jendrossek, D. , Hanzlik, M. , and Schuler, D. (2005) The presumptive magnetosome protein Mms16 is a poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate) granule‐bound protein (phasin) in Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense . J Bacteriol 187: 2416–2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, E. , Henne, A. , Cramm, R. , Eitinger, T. , Friedrich, B. , and Gottschalk, G. (2003) Complete nucleotide sequence of pHG1: a Ralstonia eutropha H16 megaplasmid encoding key enzymes of H(2)‐based ithoautotrophy and anaerobiosis. J Mol Biol 332: 369–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.K. , and Mallick, N. (2009) SCL‐LCL‐PHA copolymer production by a local isolate, Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC 7925. Biotechnol J 4: 703–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater, S.C. , Voige, W.H. , and Dennis, D.E. (1988) Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of the Alcaligenes eutrophus H16 poly‐beta‐hydroxybutyrate biosynthetic pathway. J Bacteriol 170: 4431–4436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbuchel, A. , and Fuchtenbusch, B. (1998) Bacterial and other biological systems for polyester production. Trends Biotechnol 16: 419–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbuchel, A. , and Hein, S. (2001) Biochemical and molecular basis of microbial synthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates in microorganisms. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol 71: 81–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbuchel, A. , Aerts, K. , Babel, W. , Follner, C. , Liebergesell, M. , Madkour, M.H. , et al (1995) Considerations on the structure and biochemistry of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoic acid inclusions. Can J Microbiol 41(Suppl. 1): 94–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbe, J. , Tian, J. , He, A. , Sinskey, A.J. , Lawrence, A.G. , and Liu, P. (2005) Nontemplate‐dependent polymerization processes: polyhydroxyalkanoate synthases as a paradigm. Annu Rev Biochem 74: 433–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudesh, K. , Abe, H. and Doi, Y. (2000) Synthesis, structure and properties of polyhydroxyalkanoates: biological polymers. Prog Polym Sci 25: 1503–1555. [Google Scholar]

- Suriyamongkol, P. , Weselake, R. , Narine, S. , Moloney, M. , and Shah, S. (2007) Biotechnological approaches for the production of polyhydroxyalkanoates in microorganisms and plants – a review. Biotechnol Adv 25: 148–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sznajder, A. , Pfeiffer, D. , and Jendrossek, D. (2015) Comparative proteome analysis reveals four novel polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) granule‐associated proteins in Ralstonia eutropha H16. Appl Environ Microbiol 81: 1847–1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J. , He, A. , Lawrence, A.G. , Liu, P. , Watson, N. , Sinskey, A.J. , and Stubbe, J. (2005a) Analysis of transient polyhydroxybutyrate production in Wautersia eutropha H16 by quantitative Western analysis and transmission electron microscopy. J Bacteriol 187: 3825–3832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian, S.J. , Lai, W.J. , Zheng, Z. , Wang, H.X. , and Chen, G.Q. (2005b) Effect of over‐expression of phasin gene from Aeromonas hydrophila on biosynthesis of copolyesters of 3‐hydroxybutyrate and 3‐hydroxyhexanoate. FEMS Microbiol Lett 244: 19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirapelle, E.F. , Muller‐Santos, M. , Tadra‐Sfeir, M.Z. , Kadowaki, M.A. , Steffens, M.B. , Monteiro, R.A. , et al (2013) Identification of proteins associated with polyhydroxybutyrate granules from Herbaspirillum seropedicae SmR1–old partners, new players. PLoS ONE 8: e75066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino, K. , Saito, T. , Gebauer, B. , and Jendrossek, D. (2007) Isolated poly(3‐hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) granules are complex bacterial organelles catalyzing formation of PHB from acetyl coenzyme A (CoA) and degradation of PHB to acetyl‐CoA. J Bacteriol 189: 8250–8256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushimaru, K. , Motoda, Y. , Numata, K. , and Tsuge, T. (2014) Phasin proteins activate Aeromonas caviae polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) synthase but not Ralstonia eutropha PHA synthase. Appl Environ Microbiol 80: 2867–2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushimaru, K. , Watanabe, Y. , Hiroe, A. , and Tsuge, T. (2015) A single‐nucleotide substitution in phasin gene leads to enhanced accumulation of polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) in Escherichia coli harboring Aeromonas caviae PHA biosynthetic operon. J Gen Appl Microbiol 61: 63–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandamme, P. , and Coenye, T. (2004) Taxonomy of the genus Cupriavidus: a tale of lost and found. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 54: 2285–2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl, A. , Schuth, N. , Pfeiffer, D. , Nussberger, S. , and Jendrossek, D. (2012) PHB granules are attached to the nucleoid via PhaM in Ralstonia eutropha . BMC Microbiol 12: 262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. , Sheng, X. , Equi, R.C. , Trainer, M.A. , Charles, T.C. , and Sobral, B.W. (2007) Influence of the poly‐3‐hydroxybutyrate (PHB) granule‐associated proteins (PhaP1 and PhaP2) on PHB accumulation and symbiotic nitrogen fixation in Sinorhizobium meliloti Rm1021. J Bacteriol 189: 9050–9056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. , Wu, H. , Chen, J. , Zhang, J. , Yao, Y. , and Chen, G.Q. (2008) A novel self‐cleaving phasin tag for purification of recombinant proteins based on hydrophobic polyhydroxyalkanoate nanoparticles. Lab Chip 8: 1957–1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. , Wang, Z.H. , Shen, C.Y. , You, M.L. , Xiao, J.F. , and Chen, G.Q. (2010) Differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells grown in terpolyesters of 3‐hydroxyalkanoates scaffolds into nerve cells. Biomaterials 31: 1691–1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse, A.M. , Procter, J.B. , Martin, D.M. , Clamp, M. , and Barton, G.J. (2009) Jalview Version 2–a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 25: 1189–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei, D.X. , Chen, C.B. , Fang, G. , Li, S.Y. , and Chen, G.Q. (2011) Application of polyhydroxyalkanoate binding protein PhaP as a bio‐surfactant. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 91: 1037–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek, R. , Pries, A. , Steinbuchel, A. , and Mayer, F. (1995) Analysis of a 24‐kilodalton protein associated with the polyhydroxyalkanoic acid granules in Alcaligenes eutrophus . J Bacteriol 177: 2425–2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q. , Wang, Y. , and Chen, G.Q. (2009) Medical application of microbial biopolyesters polyhydroxyalkanoates. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol 37: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Y.C. , Yao, Y.C. , Zhan, X.Y. , and Chen, G.Q. (2010) Application of polyhydroxyalkanoates nanoparticles as intracellular sustained drug‐release vectors. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 21: 127–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabuuchi, E. , Kosako, Y. , Yano, I. , Hotta, H. , and Nishiuchi, Y. (1995) Transfer of two Burkholderia and an Alcaligenes species to Ralstonia gen. Nov.: proposal of Ralstonia pickettii (Ralston, Palleroni and Doudoroff 1973) comb. Nov., Ralstonia solanacearum (Smith 1896) comb. Nov. and Ralstonia eutropha (Davis 1969) comb. Nov. Microbiol Immunol 39: 897–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamane, T. , Chen, X.‐F. , and Ueda, S. (1996) Polyhydroxyalkanoate synthesis from alcohols during the growth of Paracoccus denitrificans . FEMS Microbiol Lett 135: 207–211. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X. , Zhao, K. , and Chen, G.Q. (2002) Effect of surface treatment on the biocompatibility of microbial polyhydroxyalkanoates. Biomaterials 23: 1391–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.C. , Zhan, X.Y. , Zhang, J. , Zou, X.H. , Wang, Z.H. , Xiong, Y.C. , et al (2008) A specific drug targeting system based on polyhydroxyalkanoate granule binding protein PhaP fused with targeted cell ligands. Biomaterials 29: 4823–4830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York, G.M. , Junker, B.H. , Stubbe, J.A. , and Sinskey, A.J. (2001a) Accumulation of the PhaP phasin of Ralstonia eutropha is dependent on production of polyhydroxybutyrate in cells. J Bacteriol 183: 4217–4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York, G.M. , Stubbe, J. , and Sinskey, A.J. (2001b) New insight into the role of the PhaP phasin of Ralstonia eutropha in promoting synthesis of polyhydroxybutyrate. J Bacteriol 183: 2394–2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]