Abstract

Significant advances in our understanding of transient ischemic attack (TIA) have taken place since it was first recognized as a major risk factor for stroke during the late 1950's. Recently, numerous studies have consistently shown that patients who have experienced a TIA constitute a heterogeneous population, with multiple causative factors as well as an average 5–10% risk of suffering a stroke during the 30 days that follow the index event. These two attributes have driven the most important changes in the management of TIA patients over the last decade, with particular attention paid to effective stroke risk stratification, efficient and comprehensive diagnostic assessment, and a sound therapeutic approach, destined to reduce the risk of subsequent ischemic stroke. This review is an outline of these changes, including a discussion of their advantages and disadvantages, and references to how new trends are likely to influence the future care of these patients.

Keywords: transient ischemic attack, TIA, stroke risk stratification, antiplatelet therapy, anticoagulants, arterial revascularization

Introduction

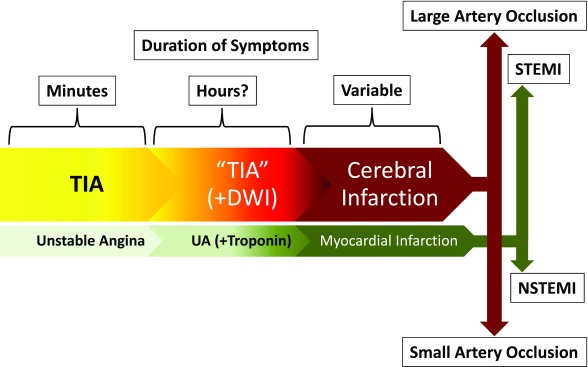

The original description of TIA as a clinical entity dates back to a 1958 report by C. Miller Fisher, in which he described it as cerebral ischemic episode that "... may last from a few seconds up to several hours, the most common duration being a few seconds up to five or 10 minutes…" 1. Our understanding of TIAs has increased since then, with a growing realization that they represent a warning about the risk of ischemic stroke, an ominous prelude to an impending cerebrovascular catastrophe, but also the opportunity to prevent a disabling event 2– 5. The current definition of TIA precludes its use as a diagnosis in patients whose imaging studies display acute ischemic tissue injury (i.e. infarction), irrespective of the resolution of their symptoms 6. This shift from a phenomenologic to an anatomoclinical view may seem frivolous, but it underscores the importance of TIA as an opportunity for stroke prevention, much like unstable angina heralds myocardial infarction (MI) ( Figure 1) 7. This similarity is the backdrop for our discussion of the most important advances in the management of TIAs: a) improved predictive models of stroke risk (i.e. stroke risk stratification), b) optimal algorithms for evaluation (i.e. comprehensive assessment), and c) effective treatment strategies (i.e. therapeutic approach).

Figure 1. Comparison of the anatomoclinical relationship between transient ischemic attack (TIA) and cerebral infarction with the acute coronary syndromes.

TIAs can be considered the equivalent of unstable angina, with symptoms lasting for a few minutes and then abating. They often have a longer duration and an imaging counterpart (positive diffusion weighted imaging [DWI]), which may be reversible. When the ischemic process is sufficiently severe, it results in permanent injury to the brain tissue. This "ischemic continuum" mirrors the findings in acute coronary syndromes, even to the point that cerebral infarctions resulting from large arterial occlusions are emergently managed endovascularly, just like an ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), while the smaller infarctions are handled by non-interventional means, just like a non-STEMI (NSTEMI).

Stroke risk stratification

Etiopathogenic variability

Unlike unstable angina, TIAs can result from very different causative factors, each with its own particular risk profile 8, 9. Therefore, the care of patients with TIA requires etiopathogenic evaluation and individualized estimation of their stroke risk. It seems intuitive that if a) TIA is to be considered the warning (i.e. a "threat" or "alarm") of an impending ischemic stroke and b) its assigned stroke risk depends on its pathogenic process, prevention strategies should match stroke subtype. Stroke subtype classification is best carried out by applying the scheme designed for the Trial of ORG-10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) 8. Unfortunately, the likelihood of correctly identifying stroke subtype in the emergency department (ED) approximates 60%, making it impractical for use before patients are fully evaluated 10.

Thus, although the risk of stroke following a TIA is estimated at 5–10%, and despite 15–20% of ischemic stroke patients reporting a premonitory TIA, their etiopathogenic heterogeneity and inherent variability of stroke risk is illustrated by each patient profile 4, 11– 13. This has led to the development of various scoring systems for stroke risk stratification 2– 5, 7, 11, 12, 14, 15, all striving to satisfy the following attributes: a) ability to discriminate between high and low stroke risk, b) consistency of performance across clinical scenarios 15, and c) rapid applicability, since time is of the essence in the ED 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 12, 14.

Stroke risk scoring systems

The scoring systems from the 1990's were concerned with long-term stroke risk 16– 21. Later, increasing appreciation of TIA as a medical emergency led to interest in quantifying short-term risk and early stroke prevention 3, 22– 30. The first wave of scoring systems, including the California Risk Score (CRS) 3, ABCD 30, and ABCD 2 27, comprised stroke risk factors (i.e. age, blood pressure, and diabetes mellitus) and semiologic variables (i.e. clinical features and duration of symptoms) ( Table 1). The CRS showed progressively higher scores to be associated with an increasing proportion of stroke events adjudicated during a 90-day follow up period but did not include a final stratification into a high- and low-risk dichotomy 3. The ABCD (i.e. age, blood pressure, clinical features, and duration of symptoms) score adjudicated no stroke events with ABCD scores <4, while the 7-day risk of stroke increased to 35.5% with ABCD scores >6 30. In another population, ABCD scores <2 were associated with no 30-day stroke events, the risk progressively increasing with higher scores, reaching 31.3% in patients with ABCD scores of 6 31. The most significant finding was an 8-fold increase with ABCD ≥5 31, suggesting the presence of a "tipping point" at which stroke risk increases exponentially. The introduction of the ABCD score was rapidly embraced by the community of vascular neurologists and has provided the seminal platform for the introduction of progressively more complex scoring systems. The combination of the CRS and the ABCD scores resulted in the ABCD 2 score, which stratified three different risk groups as low (<4), moderate (4–5), and high (6–7) risk 27.

Table 1. Comparison of the different stroke risk scoring systems used in patients with transient ischemic attack (TIA).

See text and Figure 2 for additional information. CIP, clinical imaging-based prediction; CRS, California Risk Score; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DWI, diffusion weight imaging; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

| System | Semiologic Variables | Risk

Factors |

Imaging

Findings |

Score | % Stroke Risk

(Period) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRS

(2000) 3 |

Duration >10 minutes

Weakness Speech Impairment |

Age >60

Diabetes |

N/A | 1

2 3 4 5 |

3

7 11 15 34 (90 day) |

| ABCD

(2005) 30 |

Weakness

Speech Duration |

Age >60

SBP >140 mmHg or DBP >90 mmHg |

N/A | 1–3

4 5 6 |

0

2.2 16.3 35.5 (7 day) |

| ABCD2

(2007) 27 |

Weakness

Speech Duration |

Age >60

SBP >140 mmHg or DBP >90 mmHg Diabetes |

N/A | 1–3

4–5 6–7 |

1.0

4.1 8,1 (2 day) |

| ABCD2 + MRI

(2007) 23 |

Weakness

Speech Duration |

Age >60

SBP >140 mmHg or DBP >90 mmHg Diabetes |

+DWI | 1–4

5–6 7–9 |

0

5.4 32.1 (90 day) |

| CIP

(2009) 22 |

Weakness

Speech Duration |

Age >60

SBP >140 mmHg or DBP >90 mmHg Diabetes |

+DWI | >3

+DWI >3 & +DWI |

2.0

4.9 14.9 (7 day) |

| ABCD2-I

(2010) 26 |

Weakness

Speech Duration |

Age >60

SBP >140 mmHg or DBP >90 mmHg Diabetes |

+DWI or +CT | 1–2

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

0

1.2 1.6 2.0 3.7 4.0 12.3 15.1 12.2 (7 day) |

| ABCD3

(2010) 28 |

Weakness

Speech Duration |

Age >60

SBP >140 mmHg or DBP >90 mmHg Diabetes Recent TIA |

N/A | 1–3

4–5 6–9 |

1

2 6 (90 day) |

| ABCD3-I

(2010) 28 |

Weakness

Speech Duration |

Age >60

SBP >140 mmHg or DBP >90 mmHg Diabetes Recent TIA |

+DWI or

carotid stenosis |

1–3

4–7 8–13 |

1

2 8 (90 day) |

| ABCDE⊕

(2010) 25 |

Weakness

Speech Duration Etiology |

Age >60

SBP >140 mmHg or DBP >90 mmHg Diabetes |

+DWI | 1–3

4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

0

7 15 3 17 20 28 24 18 25 (90 day) |

However, the predictability of these scores was not optimal and they only partially fulfilled the criteria outlined earlier. Concurrently, abnormal diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was found to correlate with stroke risk 32, 33. Thus, the addition of a DWI-positive point to the ABCD 2 score resulted in a system whose tiers had different 90-day stroke risks (i.e. 0% for scores <4 and up to 32.1% for scores of 7–9) and, additionally, different 90-day risks for functional impairment, an outcome not measured by the original ABCD 2 score 23. Imaging-related stratification improvement has been replicated using two other systems, the clinical imaging-based prediction (CIP) model 22 and the ABCD 2-I 26.

The next wave of scoring systems improved the predictability of stroke risk by including diagnostic information as it became available 28. The ABCD 3 added the occurrence of a TIA within the preceding week to the ABCD 2 score, but the results were disappointing 28. However, the same group added two more imaging variables (i.e. DWI lesions and carotid stenosis) to the ABCD 3 model, showing that ABCD 3-I was superior to previous scores in predicting stroke at 7, 28, and 90 days 28. A similar approach to stroke risk stratification involved the Alberta Stroke Prevention in TIAs and Mild Strokes (ASPIRE) intervention, which assigned a high-risk denomination to patients with a) ABCD 2 scores ≥4, b) motor or speech symptoms lasting >5 minutes, or c) atrial fibrillation (AF) 24. However, ASPIRE allocated over three-quarters of patients to the high-risk category, cancelling out the benefit of triaging TIA patients.

The most recent initiative involves the addition of "etiology" to an algorithm that already includes all the variables listed above 25. The ABCDE⊕ scoring system was designed by adding two variables to the ABCD score: a) "etiology", which included a point-weighting of each particular stroke subtype based on published data 34, and b) "DWI-positivity", which consisted of arbitrarily assigning three points to a positive MRI based on inferential conclusions from published data 25, 35. Setting an arbitrary boundary of >6 points to designate high-risk patients, this system compared favorably with both ABCD 2 (i.e. statistically significant) and ABCD (i.e. trend only) in identifying TIA patients at high risk for stroke ( Table 1) 25.

Perspective and practical approach to stroke risk prediction

Stroke risk stratification of patients with TIA, reliably identifying those more likely to benefit from urgent intervention, is a subject of considerable importance in vascular neurology. At the bedside, it is useful to approach stroke risk stratification by systematically considering the three domains that include the variables that comprise the scoring systems described ( Figure 2): a) risk factors (i.e. age, hypertension, diabetes, AF, and previous TIA), b) semiologic variables (i.e. type of symptoms and signs and duration of deficit), and c) imaging findings (i.e. DWI lesions, carotid stenosis, and etiology).

In applying a domain-driven approach to stroke risk assessment, it is possible to simultaneously address the components of all of the scoring systems described without actually being bound by any one of them at the expense of others. It can be argued that the disadvantage is that it may not be possible to equate every single clinical scenario with a numerical prediction of stroke risk. On the other hand, arriving at a numerical representation of the stroke risk does not seem to be as important as identifying which patients have a greater than minimal risk, a clinical task that requires the expert formulation of a more qualitative view of the patient as an individual 36– 43. This approach seems supported by existing experience in comparing the simultaneous application of the various stroke risk scoring systems. Recent reports by a European consortium of vascular neurology investigators, the "Proyecto Español del Manejo y Evaluación de los Pacientes con un Ataque Isquémico Transitorio" (PROMAPA), underscore the importance of going beyond the scoring systems, particularly in unstable patients and those with recurrent TIAs 29, 44.

The limitation of the various scoring systems is not surprising when considering that a) the boundaries between the various levels of stroke risk have been set arbitrarily, b) some variables are better defined than others (e.g. blood pressure is defined as >140 mmHg systolic and/or >90 mmHg diastolic but, at which point? How many measurements does it take?), and c) the point weighting of some variables (e.g. imaging) has been derived from previous, often not replicated studies. In addition, in many clinical scenarios where TIA patients are seen for the first time, much of the information required for scoring diagnostic variables is not available, and only the simpler of the scoring systems are applicable.

Figure 2. Variables that compose the different stroke risk scoring systems.

Three domains are used to group the components contained within the different stroke risk scoring systems. The earlier systems (i.e. California Risk Score [CRS], “age, blood pressure, clinical features, and duration of symptoms” [ABCD], and ABCD 2) only included components from the “risk factors” and “semiologic variables” domains. The more recent ones (i.e. ABCD 2-MRI, clinical imaging-based prediction [CIP], ABCD 2-I, ABCD 3-I, and ABCDE⊕), shown to have better predictability, added one or more components from the “imaging findings” domain.

Comprehensive assessment

The diagnostic evaluation of TIAs revolves around the determination of the cause and mechanism of the index event. In addition, as TIA is a medical emergency worthy of urgent management, diagnostic investigations require an efficient and expedited algorithm.

Timing and location

A major topic of debate involves when, where, and how to evaluate TIA patients most effectively. The typical patient presents after the symptoms of the index event have abated, creating two conflictive considerations: a) the inconvenience and discomforts of hospitalizing a neurologically normal patient and b) the inherent risks of a protracted ambulatory evaluation 45– 50. Opinions regarding the best approach are sharply divided 51, with the proponents of an ambulatory workflow citing "cost-effectiveness" and better "resource utilization" as their main arguments 47, 52, 53. Conversely, those who favor an in-hospital process argue for "expediency of care", "patient safety", and better outcomes 46, 48, 53, 54. The most recent literature on this subject is, at best, inconclusive; both approaches have advantages and disadvantages based on two sets of variables: a) the patient's stroke risk profile and b) the clinical environment construct and capabilities. The former has been covered in the previous sections, but the latter is worthy of further discussion.

Traditionally, TIA patients present to the ED because of extensive educational campaigns consistently instructing them to "DIAL 9-1-1" upon recognition of stroke symptoms. They are then admitted for "23-hour observation" while their evaluation is completed. The benefits of this approach include a) patients have a captive audience of medical personnel who watch over them in case of a neurologic change, b) the results of the diagnostic tests are known almost immediately and can be used in real time to update the stroke risk calculation, c) the identification of a need for urgent therapeutic intervention allows rapid execution of any treatment plan, and d) there is little risk of suffering an ischemic stroke while waiting to have the tests completed (including results review) or to "fall through the cracks" because of scheduling mishaps. Experts agree that this approach is appropriate when managing high-risk TIA patients 54 but question whether it is justified for those at low risk 47, 51. Unfortunately, low scores do not necessarily translate into low stroke risk, particularly in the ED. In fact, approximately 20% of patients with ABCD 2 <4 harbor either an atherosclerotic or a cardiogenic source of stroke and 3-month stroke risk comparable to those with scores >4 37.

A recently introduced alternative environment for the evaluation of TIA patients is the TIA clinic ( Figure 3) 51, 55– 57, whose demonstrated effectiveness and beneficial impact on outcome 57, 58 depend on the following attributes:

a) Fast track access: referral of potential TIA patients must unequivocally result in immediate appointments 51, 53– 57. It is unreasonable to consider TIA as an emergency and simultaneously subject the patient to the inherent delays of ambulatory care. Thus, the established metrics are appointments made within 24 hours for high-risk patients and within 48 hours for others 59– 61.

b) Specialist (i.e. vascular neurologist) assessment: there is simply no substitute for experience. The diagnosis of TIA can be challenging 62, 63, as many other conditions may "mimic" its presentation 64– 71. Moreover, its identification must be followed by a cerebrovascular localization diagnosis, which has a direct impact on the etiopathogenic assessment and stroke subtype diagnosis 72. Only a specialist in cerebrovascular disorders can rightfully prioritize the diagnostic and therapeutic needs of a TIA patient ( Figure 3) 73, 74.

c) Rapid access to diagnostic investigations: once a patient is evaluated by a specialist, diagnostic investigations must be carried out very quickly ( Figure 3). Such a workflow can be challenging, particularly when competing for time slots or when, in the case of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), another specialist's participation is required. Once completed, the vascular neurologist must have rapid access to the results in order to be able to make the next set of decisions ( Figure 3).

d) Multidisciplinary network: there must be access to a variety of consultants from other disciplines, particularly cardiologists, neurosurgeons, and vascular surgeons. This implies that these specialists are also available at a moment's notice to evaluate the patient ( Figure 3).

e) Educational programs: patients must be educated in relevant topics, such as stroke risk factors and their management, beneficial lifestyle changes, and interventions (i.e. medications and procedures) used in the prevention of stroke.

Figure 3. Optimal workflow in a transient ischemic attack (TIA) clinic.

A potential TIA patient is referred to the clinic and his visit with the vascular neurologist is expedited (lightning bolt). Upon assessment, if the patient is found not to have had a TIA, his care is diverted to an alternative clinical pathway. If the vascular neurologist determines that the patient has had a TIA, he can proceed by immediately requesting the appropriate diagnostic procedures. Test completion and results reporting are also expedited (lightning bolt), allowing the vascular neurologist to quickly review them and decide on a treatment strategy tailored to the patient's risk profile. Management includes patient and family education as well as appropriate referral to pre-specified specialists.

Depth of diagnostic evaluation

The battery of diagnostic tests required for TIA evaluation is geared at uncovering the cause and mechanism (i.e. stroke subtype classification) of the index event. Most TIA patients fall into either the large artery atherothromboembolic (~30–40% of cases) or the cardiogenic (~15–20%) categories (i.e. TOAST) 75, the two subtypes that pose the greatest stroke risk following TIA 34. Therefore, the priorities of such diagnostic evaluation involve examination of the cerebral arterial system 76, 77 and a search for cardiogenic sources of embolization 78– 86. Other tests (e.g. coagulation studies), although certainly important, are easier to carry out, only infrequently lead to positive findings, and rarely carry a sense of urgency.

The cerebral vasculature can be evaluated noninvasively with magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), computed tomography angiography (CTA), or neurovascular ultrasound (i.e. extracranial carotid and vertebral color Doppler and transcranial Doppler ultrasound). The choice of which to use depends on a) the clinical scenario, b) the specific vascular pathology suspected, and c) the imaging resources available at any particular clinical site. One advantage of MRA is that it can be completed concurrently with MRI, which is the stroke imaging technique of choice 35, 75, 76, 87– 92 and a component of several stroke risk scoring systems 22– 26. However, CTA has also been shown to be useful in the early assessment of TIA 93 as well as for patients who cannot undergo MRI. Patients with renal insufficiency who cannot receive contrast (either iodinated or gadolinium-based) can often only be evaluated using ultrasound. When noninvasive cerebrovascular imaging is inconclusive or when it indicates pathology that requires intervention, cerebral catheterization and angiography remains an important tool for evaluation and treatment selection 94, 95. Although cerebral angiography is invasive and certainly with some risks, the information obtained from this technique is often not available by any other means.

As for cardiogenic TIA, the introduction of TEE represents a major diagnostic advancement due to a) increased resolution and sensitivity for left atrial pathology, including the left atrial appendage and the interatrial septum, and b) capability for imaging the aortic arch, uncovering the presence of complex atherosclerotic plaques as a source of artery-to-artery cerebral embolism 80– 82, 84, 85. Finally, the detection of occult paroxysmal AF in patients with unexplained events correlates with the length of the cardiac rhythm assessment 86, improved by 7- to 30-day cardiac event monitors 96– 101 and even more so by implantable loop recorders 83, 97– 99, 101.

Therapeutic strategies

General measures

Despite the significant risk of stroke during the first week following a TIA 3, 4, 12, 102, stroke prevention can be optimized (i.e. stroke risk reduction of ~80%) by rapid and intensive interventions 57, 58, 103. Undoubtedly, tailoring therapeutic measures to the specific etiopathogenic mechanism (i.e. stroke subtype) is the most desirable strategy. However, since such assessment cannot be made with certainty in the ED 10, the immediate management of patient presentation should be viewed as part of a continuum, with certain specific measures (e.g. antiplatelet therapy) possible with minimal risk and potentially significant benefit as soon as the first CT scan is reviewed 104– 107.

Some general measures of care don't even require any imaging to be completed for their implementation. For example, isotonic crystalloid solutions can easily be administered to TIA patients as soon as they arrive in the ED. Not only is this inexpensive and low-risk step in line with the existing guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke 108 but it also addresses the fact that approximately 50% of stroke patients present with measurable dehydration 109– 115. Along the same lines, any patient with TIA should be given "best medical management" of oxygenation, careful blood pressure control, and serum glucose regulation, just as if they had suffered a bona fide ischemic stroke 108.

Target-specific measures

Antiplatelet therapy. Early antithrombotic therapy leads to about 80% relative reduction of stroke risk in patients with TIA, although the best strategy continues to be a matter of debate 57, 58. In general, aspirin has been thought to reduce the odds of a subsequent stroke by approximately 20–25% in patients with previous TIA or stroke 116 and doses of 50–325 mg per day continue to be recommended due to their lower risk of hemorrhagic side effects 117. There is increasing evidence, however, that aspirin is the key interventional step in reducing the early risk of stroke following TIA, with yields of 60% overall relative risk reduction and 70% reduction of disabling or fatal strokes 103. In parallel, the Fast Assessment of Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack to prevent Early Recurrence (FASTER) trial provided evidence that aspirin plus clopidogrel may be substantially beneficial in the hyperacute treatment of patients with TIA 118. Similar results were reported by the Clopidogrel with Aspirin in Acute Minor Stroke of Transient Ischemic Attack (CHANCE) study 119, with benefit that persisted at one year of follow up 120. Another ongoing trial with a similar aim, the Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke (POINT) study, has already recruited about 80% of its target sample size and results should be available within 18–24 months 121. Patients with large artery atherosclerosis 8 have been shown by several studies to benefit from double antiplatelet therapy 118, 122, 123. That said, more is not necessarily better, and the recently reported (not yet published) Triple Antiplatelets for Reducing Dependency after Ischemic Stroke (TARDIS) study failed to show a benefit of adding dipyridamole to aspirin and clopidogrel for stroke risk reduction 124, 125. The results of TARDIS are not surprising since, although shown to be beneficial in combination with low-dose aspirin 126, 127, dipyridamole has not been found to be superior to clopidogrel in reducing the risk of stroke 128.

In the last few years, there has been considerable interest in the study of other antiplatelet agents for secondary stroke prevention 129– 133. Cilostazol, an agent similar to dipyridamole, has been shown in two Asian studies to be superior to aspirin in reducing vascular events in patients with stroke, with the caveat that those results may not be applicable to other populations. The SOCRATES study showed ticagrelor, a PY2 inhibitor similar to clopidogrel, to be approximately 30% more effective than and equally as safe as aspirin in reducing major adverse events in patients with TIA and atherosclerotic stenosis 129– 132.

Anticoagulants. Vitamin K antagonists, namely warfarin, have been in use for many years, and their main applications have been in patients with AF, mechanical heart valve prostheses, and other causes of cardiogenic brain embolism. In patients with non-valvular AF (NVAF), warfarin reduces the risk of stroke by approximately 67% in comparison to no treatment and by 37% when compared with antiplatelet therapy 134. The indications for warfarin in other scenarios of cardiac dysfunction are less clearly supported by the literature but reasonable to consider on an individual basis: a) severe left atrial enlargement (LAE), particularly those with spontaneous echo contrast 135– 143, b) abnormally low flow in the left atrial appendage (LAA) 144– 147, and c) left ventricular (LV) dysfunction 148– 153.

Recently, two other classes of oral anticoagulants for the treatment of patients with NVAF have become available ( Table 2): direct thrombin (i.e. dabigatran) 154– 158 and factor Xa (i.e. apixaban 159– 164, rivaroxaban 165, and edoxaban 166, 167) inhibitors. These medications have all been successfully tested against warfarin in patients with NVAF, and their appeal is based on the fact that they have shorter half-lives, fewer drug and food interactions, and do not require laboratory therapeutic monitoring 154– 167. Presently, only dabigatran has a specifically designated reversing agent (i.e. idarucizumab – Praxbind®) 168, a fact that adds a unique dimension to its use. Unfortunately, the use of these new anticoagulants is not without its own set of problems. For instance, they are all excreted via the kidneys, so care must be exercised in their use in patients with renal insufficiency 160.

Table 2. Comparison of the principal trials that have studied the new generation of anticoagulants.

See text for more detailed information. ARISTOTLE, Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation; AVERROES, Apixaban Versus Acetylsalicylic Acid to Prevent Stroke in Atrial Fibrillation Patients Who Have Failed or Are Unsuitable for Vitamin K Antagonist Treatment; BID, bis in die; CHADS2, congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years, diabetes mellitus, stroke (double weight); ENGAGE AF, Effective Anticoagulation with Factor Xa Next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation; RE-LY, Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy; ROCKET AF, Rivaroxaban Once Daily Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared with Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

| Drug | Dabigatran

(110 mg BID) |

Dabigatran

(150 mg BID) |

Apixaban

(5 mg BID) |

Apixaban

(5 mg BID) |

Rivaroxaban

(20 mg daily) |

Edoxaban

(60 mg daily) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | RE-LY 154 | RE-LY 154 | AVERROES 159 | ARISTOTLE 161 | ROCKET-AF 165 | ENGAGE-AF 166 |

| Mean age (years) | 71.4 | 71.5 | 70 | 70 | 73 | 72 |

| Mean CHADS2 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 3.5 | 2.8 |

|

Previous

TIA/stroke (%) |

20 | 20 | 14 | 19 | 55 | 28.1 |

|

Mean time in target

range (%) |

64 | 64 | N/A | 62 | 58 | 68.4 |

|

Rate of stroke/

embolism (%/year) |

1.5 v. 1.69 | 1.11 v. 1.69 | 1.6 v. 3.7 | 1.27 v. 1.60 | 1.7 v. 2.2 | 1.18 v. 1.50 |

|

Rate of major

bleeding (%/year) |

2.71 v. 3.36 | 3.11 v. 3.36 | 1.4 v. 1.2 | 2.13 v. 3.09 | 3.6 v. 3.4 | 2.75 v. 3.43 |

|

Mortality from any

cause (%/year) |

3.75 v. 4.13 | 1.9 v 2.2 | 3.5 v. 4.4 | 3.52 v. 3.94 | 1.9 v. 2.2 | 3.99 v. 4.35 |

Successful anticoagulation of patients with AF depends on careful benefit versus risk assessment. This is aided by available scoring systems, namely the CHA 2DS 2-VASc score 169, 170 (i.e. a "second generation" improvement of the original CHAD 2 score 171) to determine stroke risk and the HAS-BLED score to quantify risk of hemorrhagic complications ( Table 3) 172. Scoring allows characterization of yearly risks along stepwise progressive scales, which can then be easily compared for the purposes of clinical decisions 169, 170, 172. Typically, calculation of the HAS-BLED score requires more attention to detail, since its components have been more precisely defined 172. For example, while in CHA 2DS 2-VASc the "H" stands for "hypertension" as an active diagnosis 169, in the HAS-BLED the "H" stands for "uncontrolled hypertension" (i.e. >160 mmHg systolic) 172. Moreover, the original definition does not specify over what period, but it seems reasonable that, in order to contribute to the bleeding risk, the blood pressure would have to be persistently elevated. Consequently, not only is a single measurement insufficient to assign a point but, practically, aggressive blood pressure control should reduce the HAS-BLED score ( Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of the two scoring systems most commonly used to assess benefit versus risk of anticoagulation in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation.

HAS-BLED definitions 171:

Hypertension = "'Uncontrolled hypertension' as evidenced by >160 mmHg systolic."

Abnormal renal function = "Chronic dialysis, renal transplantation, or serum creatinine ≥200 μmol/L"

Abnormal liver function = "Chronic hepatic disease (e.g. cirrhosis) or biochemical evidence of significant hepatic derangement (e.g. bilirubin >2Xupper limit normal, and so forth."

Stroke = "Previous history, particularly lacunar"

Bleeding history or predisposition = "Any bleeding requiring hospitalization and/or causing a decrease in haemoglobin level >2 g/L and/or requiring blood transfusion that was not a hemorrhagic stroke"

Labile international normalized ratio (INR) = "Therapeutic time in range <60%"

Elderly = ">65 years"

Drugs = "Antiplatelet agents, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs"

Alcohol excess= "≥8 units alcoholic consumption per week"

AP, angina pectoris; LVD, left ventricular dysfunction; MI, myocardial infarction; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; TE, thromboembolism; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

| CHA2DS2-VASc 169 | HAS-BLED 172 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria [POINTS] | Stroke & TE Risk (% Yearly) | Criteria [POINTS] | Bleeding Risk (% Yearly) |

| Congestive heart failure/LVD [1] | 1...................1.3 | Hypertension [1] | 1...................1.02 |

| Hypertension [1] | 2...................2.2 | Abnormal renal [1] or liver [1] | 2...................1.88 |

| Age ≥ 75 years [2] | 3...................3.2 | Stroke [1] | 3...................3.74 |

| Diabetes mellitus [1] | 4...................4.0 | Bleeding [1] | 4...................8.70 |

| Stroke/TIA/TE [2] | 5...................6.7 | Labile INRs [1] | 5...................12.5 |

| Vascular disease (MI, PVD, AP) [1] | 6...................9.8 | Elderly [1] | |

| Age 65–74 years [1] | 7...................9.6 | Drugs [1] or alcohol excess [1] | |

| Sex category (female) [1] | 7...................6.7 | ||

| 9...................15.2 | |||

Arterial revascularization. There is a robust body of knowledge to indicate that patients who have experienced a TIA due to an ipsilateral carotid atherosclerotic stenosis of more than 50% benefit from revascularization either by carotid endarterectomy (CEA) 173, 174 or by carotid artery stenting (CAS) 174– 177. Either procedure should be carried out as soon as it is practical, preferably within two weeks of the index event 174, 178, by expert teams, in centers that perform a high volume of procedures, and with a track record of a major complicating event rate of <6% 174, 178.

In patients with TIA and extracranial vertebral artery stenosis, despite the existing literature 179– 181, the guidelines suggest that stenting be reserved for patients who remain "symptomatic" despite optimal medical therapy, including risk factor modification and antithrombotic agents 174. The recommendation for patients with intracranial atherosclerosis, even those with severe stenosis, is that they are managed with maximal medical therapy 174, based on the results of the Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis (SAMMPRIS) study 182, 183. Although it is beyond the scope of our review to undermine the SAMMPRIS study, we must indicate the number of criticisms made of its design and execution 184– 188 and suggest that additional study of this subject is needed.

Vascular risk factor modification. Blood pressure control is recommended to reduce the risk of stroke in patients with TIA 174. The desirable blood pressure is uncertain in the few hours that follow the index event, when a "normal" level may aggravate ischemia because of abnormal autoregulation or upstream pressure gradients. Subsequently, blood pressure should be reduced to <140/90 mmHg in most patients and <130/80 mmHg in diabetics 174.

Intensive lipid-lowering therapy with statins should be instituted in patients with atherosclerosis and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) >100 mg/dL 174. Moreover, early use of statins has been shown to benefit patients with TIA without causing undue adverse events 189– 191, although not uniformly (e.g. the FASTER study failed to show any benefit from simvastatin) 118. An exciting prospect is the introduction of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors which, when added to statins, seem to result in a more effective reduction of LDL-C 192, 193, with potential beneficial effect in stroke risk reduction 194– 199.

Diabetes and the metabolic syndrome have been associated with an increased risk of stroke 200. Patients with TIA should be screened for diabetes by means of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and for obesity by measuring the body mass index (BMI) 174. In the future, it may be possible to predict insulin resistance in non-diabetic TIA patients by means of scoring systems 201. Recent data suggest that abnormal glycemic control may also have a negative effect on the efficacy of clopidogrel 202, and glucose reduction through diet, exercise, oral hypoglycemic agents, and insulin to a fasting <126 mg/dL is recommended 174. The pharmacologic choices for achieving glucose control are numerous and their application depends on different clinical considerations. However, in the recently published Insulin Resistance Intervention after Stroke (IRIS) study, pioglitazone was shown to reduce the risk of stroke and MI by approximately 24% in patients with recent TIA 203.

In addition to all of the previous recommendations, patients must be counselled about smoking cessation, proper diet (preferably Mediterranean), regular exercise, maintenance of appropriate BMI, and limiting alcohol consumption as measures that require their own active participation to reduce their risk of subsequent stroke 174.

Conclusion

The diagnosis of a TIA represents the recognition of a medical emergency and an opportunity to reduce the risk of stroke by decisively evaluating the patient and applying any combination of the currently available therapeutic strategies. The future is likely to show additional methods of early diagnosis, better algorithms for stroke risk stratification, and enhanced systems of care for these patients, without a dependence on hospitalization.

Editorial Note on the Review Process

F1000 Faculty Reviews are commissioned from members of the prestigious F1000 Faculty and are edited as a service to readers. In order to make these reviews as comprehensive and accessible as possible, the referees provide input before publication and only the final, revised version is published. The referees who approved the final version are listed with their names and affiliations but without their reports on earlier versions (any comments will already have been addressed in the published version).

The referees who approved this article are:

Peter Rothwell, Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Pierre Amarenco, Bichat University Hospital, Paris, France

Funding Statement

The author(s) declared that no grants were involved in supporting this work.

[version 1; referees: 2 approved]

References

- 1. Fisher CM: Intermittent Cerebral Ischemia. In: Wright ISM CH, ed. Cerebral Vascular Disease New York: Grune & Stratton,1958;81–97. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chandratheva A, Mehta Z, Geraghty OC, et al. : Population-based study of risk and predictors of stroke in the first few hours after a TIA. Neurology. 2009;72(22):1941–7. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a826ad [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johnston SC, Gress DR, Browner WS, et al. : Short-term prognosis after emergency department diagnosis of TIA. JAMA. 2000;284(22):2901–6. 10.1001/jama.284.22.2901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lisabeth LD, Ireland JK, Risser JM, et al. : Stroke risk after transient ischemic attack in a population-based setting. Stroke. 2004;35(8):1842–6. 10.1161/01.STR.0000134416.89389.9d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wu CM, McLaughlin K, Lorenzetti DL, et al. : Early risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(22):2417–22. 10.1001/archinte.167.22.2417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sacco RL, Kasner SE, Broderick JP, et al. : An updated definition of stroke for the 21st century: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44(7):2064–89. 10.1161/STR.0b013e318296aeca [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Uchiyama S: The concept of acute cerebrovascular syndrome. Front Neurol Neurosci. 2014;33:11–8. 10.1159/000351888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Adams HP, Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, et al. : Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke. 1993;24(1):35–41. 10.1161/01.STR.24.1.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Amarenco P, Bogousslavsky J, Caplan LR, et al. : New approach to stroke subtyping: the A-S-C-O (phenotypic) classification of stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27(5):502–8. 10.1159/000210433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Madden KP, Karanjia PN, Adams HP, Jr, et al. : Accuracy of initial stroke subtype diagnosis in the TOAST study. Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Neurology. 1995;45(11):1975–9. 10.1212/WNL.45.11.1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Giles MF, Rothwell PM: Transient ischaemic attack: clinical relevance, risk prediction and urgency of secondary prevention. Curr Opin Neurol. 2009;22(1):46–53. 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32831f1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Giles MF, Rothwell PM: Risk of stroke early after transient ischaemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(12):1063–72. 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70274-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brainin M, McShane LM, Steiner M, et al. : Silent brain infarcts and transient ischemic attacks. A three-year study of first-ever ischemic stroke patients: the Klosterneuburg Stroke Data Bank. Stroke. 1995;26(8):1348–52. 10.1161/01.STR.26.8.1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rothwell PM, Warlow CP: Timing of TIAs preceding stroke: time window for prevention is very short. Neurology. 2005;64(5):817–20. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152985.32732.EE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Giles MF, Rothwell PM: Systematic review and pooled analysis of published and unpublished validations of the ABCD and ABCD2 transient ischemic attack risk scores. Stroke. 2010;41(4):667–73. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.571174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kernan WN, Horwitz RI, Brass LM, et al. : A prognostic system for transient ischemia or minor stroke. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114(7):552–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-114-7-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hankey GJ, Slattery JM, Warlow CP: Transient ischaemic attacks: which patients are at high (and low) risk of serious vascular events? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 1992;55(8):640–52. 10.1136/jnnp.55.8.640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. CAPRIE Steering Committee: A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). CAPRIE Steering Committee. Lancet. 1996;348(9038):1329–39. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)09457-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kernan WN, Viscoli CM, Brass LM, et al. : The stroke prognosis instrument II (SPI-II) : A clinical prediction instrument for patients with transient ischemia and nondisabling ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2000;31(2):456–62. 10.1161/01.STR.31.2.456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van Wijk I, Kappelle LJ, van Gijn J, et al. : Long-term survival and vascular event risk after transient ischaemic attack or minor ischaemic stroke: a cohort study. Lancet. 2005;365(9477):2098–104. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66734-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weimar C, Benemann J, Michalski D, et al. : Prediction of recurrent stroke and vascular death in patients with transient ischemic attack or nondisabling stroke: a prospective comparison of validated prognostic scores. Stroke. 2010;41(3):487–93. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.562157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ay H, Arsava EM, Johnston SC, et al. : Clinical- and imaging-based prediction of stroke risk after transient ischemic attack: the CIP model. Stroke. 2009;40(1):181–6. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.521476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Coutts SB, Eliasziw M, Hill MD, et al. : An improved scoring system for identifying patients at high early risk of stroke and functional impairment after an acute transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. Int J Stroke. 2008;3(1):3–10. 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2008.00182.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Coutts SB, Sylaja PN, Choi YB, et al. : The ASPIRE approach for TIA risk stratification. Can J Neurol Sci. 2011;38(1):78–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Engelter ST, Amort M, Jax F, et al. : Optimizing the risk estimation after a transient ischaemic attack - the ABCDE⊕ score. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19(1):55–61. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03428.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Giles MF, Albers GW, Amarenco P, et al. : Addition of brain infarction to the ABCD 2 Score (ABCD 2I): a collaborative analysis of unpublished data on 4574 patients. Stroke. 2010;41(9):1907–13. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.578971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, et al. : Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2007;369(9558):283–92. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60150-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 28. Merwick A, Albers GW, Amarenco P, et al. : Addition of brain and carotid imaging to the ABCD 2 score to identify patients at early risk of stroke after transient ischaemic attack: a multicentre observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(11):1060–9. 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70240-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 29. Purroy F, Jiménez Caballero PE, Gorospe A, et al. : Prediction of early stroke recurrence in transient ischemic attack patients from the PROMAPA study: a comparison of prognostic risk scores. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;33(2):182–9. 10.1159/000334771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Flossmann E, et al. : A simple score (ABCD) to identify individuals at high early risk of stroke after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2005;366(9479):29–36. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66702-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tsivgoulis G, Spengos K, Manta P, et al. : Validation of the ABCD score in identifying individuals at high early risk of stroke after a transient ischemic attack: a hospital-based case series study. Stroke. 2006;37(12):2892–7. 10.1161/01.STR.0000249007.12256.4a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Redgrave JN, Coutts SB, Schulz UG, et al. : Systematic review of associations between the presence of acute ischemic lesions on diffusion-weighted imaging and clinical predictors of early stroke risk after transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2007;38(5):1482–8. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.477380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Redgrave JN, Schulz UG, Briley D, et al. : Presence of acute ischaemic lesions on diffusion-weighted imaging is associated with clinical predictors of early risk of stroke after transient ischaemic attack. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;24(1):86–90. 10.1159/000103121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lovett JK, Coull AJ, Rothwell PM: Early risk of recurrence by subtype of ischemic stroke in population-based incidence studies. Neurology. 2004;62(4):569–73. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000110311.09970.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Calvet D, Touzé E, Oppenheim C, et al. : DWI lesions and TIA etiology improve the prediction of stroke after TIA. Stroke. 2009;40(1):187–92. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.515817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lodha N, Harrell J, Eisenschenk S, et al. : Motor Impairments in Transient Ischemic Attack Increase the Odds of a Subsequent Stroke: A Meta-Analysis. Front Neurol. 2017;8:243. 10.3389/fneur.2017.00243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cutting S, Regan E, Lee VH, et al. : High ABCD2 Scores and In-Hospital Interventions following Transient Ischemic Attack. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra. 2016;6(3):76–83. 10.1159/000450692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhao M, Wang S, Zhang D, et al. : Comparison of Stroke Prediction Accuracy of ABCD2 and ABCD3-I in Patients with Transient Ischemic Attack: A Meta-Analysis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;26(10):2387–2395. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2017.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang C, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. : Prediction of Recurrent Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack After Noncardiogenic Posterior Circulation Ischemic Stroke. Stroke. 2017;48(7):1835–41. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.016285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sen S, Chung M, Duda V, et al. : Periodontal Disease Associated with Aortic Arch Atheroma in Patients with Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;26(10):2137–2144. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2017.04.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lavallée PC, Sissani L, Labreuche J, et al. : Clinical Significance of Isolated Atypical Transient Symptoms in a Cohort With Transient Ischemic Attack. Stroke. 2017;48(6):1495–500. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.016743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tanaka K, Uehara T, Kimura K, et al. : Differences in Clinical Characteristics between Patients with Transient Ischemic Attack Whose Symptoms Do and Do Not Persist on Arrival. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25(9):2237–42. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ottaviani M, Vanni S, Moroni F, et al. : Urgent carotid duplex and head computed tomography versus ABCD2 score for risk stratification of patients with transient ischemic attack. Eur J Emerg Med. 2016;23(1):19–23. 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Purroy F, Jiménez Caballero PE, Gorospe A, et al. : Recurrent transient ischaemic attack and early risk of stroke: data from the PROMAPA study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2013;84(6):596–603. 10.1136/jnnp-2012-304005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kapral MK, Hall R, Fang J, et al. : Predictors of Hospitalization in Patients With Transient Ischemic Attack or Minor Ischemic Stroke. Can J Neurol Sci. 2016;43(4):523–8. 10.1017/cjn.2016.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kapral MK, Hall R, Fang J, et al. : Association between hospitalization and care after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. Neurology. 2016;86(17):1582–9. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lesenskyj AM, Maxwell CR, Veznedaroglu E, et al. : An Analysis of Transient Ischemic Attack Practices: Does Hospital Admission Improve Patient Outcomes? J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25(9):2122–5. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Phan TG, Srikanth V, Cadilhac DA, et al. : Better outcomes for hospitalized patients with TIA when in stroke units: An observational study. Neurology. 2016;87(16):1745–6. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ramirez L, Kim-Tenser MA, Sanossian N, et al. : Trends in Transient Ischemic Attack Hospitalizations in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(9): pii: e004026. 10.1161/JAHA.116.004026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tibæk M, Dehlendorff C, Jørgensen HS, et al. : Increasing Incidence of Hospitalization for Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack in Young Adults: A Registry-Based Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(5): pii: e003158. 10.1161/JAHA.115.003158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Majidi S, Leon Guerrero CR, Burger KM, et al. : Inpatient versus Outpatient Management of TIA or Minor Stroke: Clinical Outcome. J Vasc Interv Neurol. 2017;9(4):49–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Buisman LR, Rijnsburger AJ, den Hertog HM, et al. : Clinical Practice Variation Needs to be Considered in Cost-Effectiveness Analyses: A Case Study of Patients with a Recent Transient Ischemic Attack or Minor Ischemic Stroke. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2016;14(1):67–75. 10.1007/s40258-015-0167-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hankey GJ, Warlow CP: Cost-effective investigation of patients with suspected transient ischaemic attacks. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 1992;55(3):171–6. 10.1136/jnnp.55.3.171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cadilhac DA, Kim J, Lannin NA, et al. : Better outcomes for hospitalized patients with TIA when in stroke units: An observational study. Neurology. 2016;86(22):2042–8. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cruz-Flores S: Acute Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack in the Outpatient Clinic. Med Clin North Am. 2017;101(3):479–94. 10.1016/j.mcna.2017.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hosier GW, Phillips SJ, Doucette SP, et al. : Transient ischemic attack: management in the emergency department and impact of an outpatient neurovascular clinic. CJEM. 2016;18(5):331–9. 10.1017/cem.2016.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lavallée PC, Meseguer E, Abboud H, et al. : A transient ischaemic attack clinic with round-the-clock access (SOS-TIA): feasibility and effects. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(11):953–60. 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70248-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, et al. : Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1432–42. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61448-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 59. Agence Nationale d'Accreditation et d'Evaluation en Santé (ANAES): [Early diagnosis and treatment of transient ischemic events in adults--May 2004]. J Mal Vasc. 2005;30:107–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions (UK): Stroke: National Clinical Guideline for Diagnosis and Initial Management of Acute Stroke and Transient Ischaemic Attack (TIA). London: Royal College of Physicians,2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Studies NIoC: Emergency department stroke and transient ischemic attack care bundle: information and implementation package. Melbourne: National Health and Medical Research Council,2009. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 62. Castle J, Mlynash M, Lee K, et al. : Agreement regarding diagnosis of transient ischemic attack fairly low among stroke-trained neurologists. Stroke. 2010;41(7):1367–70. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.577650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kraaijeveld CL, van Gijn J, Schouten HJ, et al. : Interobserver agreement for the diagnosis of transient ischemic attacks. Stroke. 1984;15(4):723–5. 10.1161/01.STR.15.4.723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Dong K, Zhang Q, Ding J, et al. : Mild encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion mimicking transient ischemic attack: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(44):e5258. 10.1097/MD.0000000000005258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Dutta D, Bowen E, Foy C: Four-year follow-up of transient ischemic attacks, strokes, and mimics: a retrospective transient ischemic attack clinic cohort study. Stroke. 2015;46(5):1227–32. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.008632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 66. Glibert N, De Keyser J: A transient ischemic attack mimic. Acta Neurol Belg. 2017;1–2 10.1007/s13760-017-0809-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Goyal N, Male S, Al Wafai A, et al. : Cost burden of stroke mimics and transient ischemic attack after intravenous tissue plasminogen activator treatment. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24(4):828–33. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 68. Amort M, Fluri F, Schäfer J, et al. : Transient ischemic attack versus transient ischemic attack mimics: frequency, clinical characteristics and outcome. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;32(1):57–64. 10.1159/000327034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hand PJ, Kwan J, Lindley RI, et al. : Distinguishing between stroke and mimic at the bedside: the brain attack study. Stroke. 2006;37(3):769–75. 10.1161/01.STR.0000204041.13466.4c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Libman RB, Wirkowski E, Alvir J, et al. : Conditions that mimic stroke in the emergency department. Implications for acute stroke trials. Arch Neurol. 1995;52(11):1119–22. 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540350113023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Nadarajan V, Perry RJ, Johnson J, et al. : Transient ischaemic attacks: mimics and chameleons. Pract Neurol. 2014;14(1):23–31. 10.1136/practneurol-2013-000782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Orjuela KD, Gomez CR: Stroke syndromes and their anatomic localization. [online]. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ranta A, Alderazi YJ: The importance of specialized stroke care for patients with TIA. Neurology. 2016;86(22):2030–1. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Sacco RL, Rundek T: The Value of Urgent Specialized Care for TIA and Minor Stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1577–9. 10.1056/NEJMe1515730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Chung J, Park SH, Kim N, et al. : Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) classification and vascular territory of ischemic stroke lesions diagnosed by diffusion-weighted imaging. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(4): pii: e001119. 10.1161/JAHA.114.001119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Yaghi S, Rostanski SK, Boehme AK, et al. : Imaging Parameters and Recurrent Cerebrovascular Events in Patients With Minor Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(5):572–8. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.4906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Adams HP, Jr, Bendixen BH, Leira E, et al. : Antithrombotic treatment of ischemic stroke among patients with occlusion or severe stenosis of the internal carotid artery: A report of the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST). Neurology. 1999;53(1):122–5. 10.1212/WNL.53.1.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wilson CA, Tai W, Desai JA, et al. : Diagnostic Yield of Echocardiography in Transient Ischemic Attack. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25(5):1135–40. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Gomez CR, Labovitz AJ: Transesophageal echocardiography in the etiologic diagnosis of stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 1991;1(2):81–7. 10.1016/S1052-3057(11)80006-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Ustrell X, Pellisé A: Cardiac workup of ischemic stroke. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2010;6(3):175–83. 10.2174/157340310791658721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Gomez CR, Tulyapronchote R, Malkoff MD, et al. : Changing trends in the etiologic diagnosis of ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 1994;4(3):169–73. 10.1016/S1052-3057(10)80181-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. McGrath ER, Paikin JS, Motlagh B, et al. : Transesophageal echocardiography in patients with cryptogenic ischemic stroke: a systematic review. Am Heart J. 2014;168(5):706–12. 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Mercé J, Garcia M, Ustrell X, et al. : Implantable loop recorder: a new tool in the diagnosis of cryptogenic stroke. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2013;66(8):665–6. 10.1016/j.rec.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Morris JG, Duffis EJ, Fisher M: Cardiac workup of ischemic stroke: can we improve our diagnostic yield? Stroke. 2009;40(8):2893–8. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.551226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Pearson AC, Labovitz AJ, Tatineni S, et al. : Superiority of transesophageal echocardiography in detecting cardiac source of embolism in patients with cerebral ischemia of uncertain etiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17(1):66–72. 10.1016/0735-1097(91)90705-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Sanna T, Diener HC, Passman RS, et al. : Cryptogenic stroke and underlying atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(26):2478–86. 10.1056/NEJMoa1313600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 87. Bristow MS, Poulin BW, Simon JE, et al. : Identifying lesion growth with MR imaging in acute ischemic stroke. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28(4):837–46. 10.1002/jmri.21507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Förster A, Wenz H, Groden C: Hyperintense Acute Reperfusion Marker on FLAIR in a Patient with Transient Ischemic Attack. Case Rep Radiol. 2016;2016: 9829823. 10.1155/2016/9829823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Grams RW, Kidwell CS, Doshi AH, et al. : Tissue-Negative Transient Ischemic Attack: Is There a Role for Perfusion MRI? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;207(1):157–62. 10.2214/AJR.15.15447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 90. Lee J, Inoue M, Mlynash M, et al. : MR perfusion lesions after TIA or minor stroke are associated with new infarction at 7 days. Neurology. 2017;88(24):2254–9. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 91. Lee SH, Nah HW, Kim BJ, et al. : Role of Perfusion-Weighted Imaging in a Diffusion-Weighted-Imaging-Negative Transient Ischemic Attack. J Clin Neurol. 2017;13(2):129–37. 10.3988/jcn.2017.13.2.129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 92. Shono K, Satomi J, Tada Y, et al. : Optimal Timing of Diffusion-Weighted Imaging to Avoid False-Negative Findings in Patients With Transient Ischemic Attack. Stroke. 2017;48(7):1990–2. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.014576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Coutts SB, Modi J, Patel SK, et al. : CT/CT angiography and MRI findings predict recurrent stroke after transient ischemic attack and minor stroke: results of the prospective CATCH study. Stroke. 2012;43(4):1013–7. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.637421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Gomez CR, Kern MJ: Cerebral catheterization: back to the future. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 1997;6(5):308–12. 10.1016/S1052-3057(97)80211-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Qureshi AI, Saleem MA, Aytaç E, et al. : The Effect of Diagnostic Catheter Angiography on Outcomes of Acute Ischemic Stroke Patients Being Considered for Endovascular Treatment. J Vasc Interv Neurol. 2017;9(3):45–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 96. Favilla CG, Ingala E, Jara J, et al. : Predictors of finding occult atrial fibrillation after cryptogenic stroke. Stroke. 2015;46(5):1210–5. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.007763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 97. Keach JW, Bradley SM, Turakhia MP, et al. : Early detection of occult atrial fibrillation and stroke prevention. Heart. 2015;101(14):1097–102. 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Miller DJ: Prolonged cardiac monitoring after cryptogenic stroke superior to 24 h ECG in detection of occult paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Evid Based Med. 2014;19(6):235. 10.1136/ebmed-2014-110074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Miller DJ, Shah K, Modi S, et al. : The Evolution and Application of Cardiac Monitoring for Occult Atrial Fibrillation in Cryptogenic Stroke and TIA. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2016;18(4):17. 10.1007/s11940-016-0400-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Ritter MA, Kochhäuser S, Duning T, et al. : Occult atrial fibrillation in cryptogenic stroke: detection by 7-day electrocardiogram versus implantable cardiac monitors. Stroke. 2013;44(5):1449–52. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.676189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Seet RC, Friedman PA, Rabinstein AA: Prolonged rhythm monitoring for the detection of occult paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in ischemic stroke of unknown cause. Circulation. 2011;124(4):477–86. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.029801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Coull AJ, Lovett JK, Rothwell PM, et al. : Population based study of early risk of stroke after transient ischaemic attack or minor stroke: implications for public education and organisation of services. BMJ. 2004;328(7435):326. 10.1136/bmj.37991.635266.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Rothwell PM, Algra A, Chen Z, et al. : Effects of aspirin on risk and severity of early recurrent stroke after transient ischaemic attack and ischaemic stroke: time-course analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2016;388(10042):365–75. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30468-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 104. Alberts MJ: Pooled RCTs: After ischemic stroke or TIA, aspirin for secondary prevention reduced early recurrence and severity. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(6):JC27. 10.7326/ACPJC-2016-165-6-027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 105. Liu Y, Fei Z, Wang W, et al. : Efficacy and safety of short-term dual- versus mono-antiplatelet therapy in patients with ischemic stroke or TIA: a meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled trials. J Neurol. 2016;263(11):2247–59. 10.1007/s00415-016-8260-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 106. Wang W, Zhang L, Liu W, et al. : Antiplatelet Agents for the Secondary Prevention of Ischemic Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack: A Network Meta-Analysis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25(5):1081–9. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 107. Zhou X, Tian J, Zhu MZ, et al. : A systematic review and meta-analysis of published randomized controlled trials of combination of clopidogrel and aspirin in transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14(1):324–32. 10.3892/etm.2017.4459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 108. Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP, Jr, et al. : Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44(3):870–947. 10.1161/STR.0b013e318284056a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Bahouth MN, Bahrainwala Z, Hillis AE, et al. : Dehydration Status is Associated With More Severe Hemispatial Neglect After Stroke. Neurologist. 2016;21(6):101–5. 10.1097/NRL.0000000000000101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 110. Kelly J, Hunt BJ, Lewis RR, et al. : Dehydration and venous thromboembolism after acute stroke. QJM. 2004;97(5):293–6. 10.1093/qjmed/hch050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Liu CH, Lin SC, Lin JR, et al. : Dehydration is an independent predictor of discharge outcome and admission cost in acute ischaemic stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21(9):1184–91. 10.1111/ene.12452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Rowat A, Graham C, Dennis M: Dehydration in hospital-admitted stroke patients: detection, frequency, and association. Stroke. 2012;43(3):857–9. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.640821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Rowat A, Smith L, Graham C, et al. : A pilot study to assess if urine specific gravity and urine colour charts are useful indicators of dehydration in acute stroke patients. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(9):1976–83. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05645.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Swerdel JN, Janevic TM, Kostis WJ, et al. : Association Between Dehydration and Short-Term Risk of Ischemic Stroke in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. Transl Stroke Res. 2017;8(2):122–30. 10.1007/s12975-016-0471-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 115. Wu FF, Hung YC, Tsai YH, et al. : The influence of dehydration on the prognosis of acute ischemic stroke for patients treated with tissue plasminogen activator. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17(1):154. 10.1186/s12872-017-0590-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 116. Antithrombotic Trialists' Collaboration: Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324(7329):71–86. 10.1136/bmj.324.7329.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. McQuaid KR, Laine L: Systematic review and meta-analysis of adverse events of low-dose aspirin and clopidogrel in randomized controlled trials. Am J Med. 2006;119(8):624–38. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.10.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Kennedy J, Hill MD, Ryckborst KJ, et al. : Fast assessment of stroke and transient ischaemic attack to prevent early recurrence (FASTER): a randomised controlled pilot trial. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(11):961–9. 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70250-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 119. Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. : Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(1):11–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa1215340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 120. Wang Y, Pan Y, Zhao X, et al. : Clopidogrel With Aspirin in Acute Minor Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack (CHANCE) Trial: One-Year Outcomes. Circulation. 2015;132(1):40–6. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 121. Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, et al. : Platelet-oriented inhibition in new TIA and minor ischemic stroke (POINT) trial: rationale and design. Int J Stroke. 2013;8(6):479–83. 10.1111/ijs.12129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Diener H, Bogousslavsky JC, Brass LM, et al. : Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9431):331–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16721-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Hankey GJ, Johnston SC, Easton JD, et al. : Effect of clopidogrel plus ASA vs. ASA early after TIA and ischaemic stroke: a substudy of the CHARISMA trial. Int J Stroke. 2011;6(1):3–9. 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2010.00535.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Bath PM, Robson K, Woodhouse LJ, et al. : Statistical analysis plan for the 'Triple Antiplatelets for Reducing Dependency after Ischaemic Stroke' (TARDIS) trial. Int J Stroke. 2015;10(3):449–51. 10.1111/ijs.12445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. TARDIS Trial Investigators, Krishnan K, Beridze M, et al. : Safety and efficacy of intensive vs. guideline antiplatelet therapy in high-risk patients with recent ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: rationale and design of the Triple Antiplatelets for Reducing Dependency after Ischaemic Stroke (TARDIS) trial (ISRCTN47823388). Int J Stroke. 2015;10(7):1159–65. 10.1111/ijs.12538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Diener HC, Cunha L, Forbes C, et al. : European Stroke Prevention Study. 2. Dipyridamole and acetylsalicylic acid in the secondary prevention of stroke. J Neurol Sci. 1996;143(1–2):1–13. 10.1016/S0022-510X(96)00308-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. ESPRIT Study Group, Halkes PH, van Gijn J, et al. : Aspirin plus dipyridamole versus aspirin alone after cerebral ischaemia of arterial origin (ESPRIT): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367(9523):1665–73. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68734-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 128. Sacco RL, Diener H, Yusuf S, et al. : Aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole versus clopidogrel for recurrent stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(12):1238–51. 10.1056/NEJMoa0805002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 129. Amarenco P, Albers GW, Denison H, et al. : Efficacy and safety of ticagrelor versus aspirin in acute stroke or transient ischaemic attack of atherosclerotic origin: a subgroup analysis of SOCRATES, a randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(4):301–10. 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30038-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 130. Easton JD, Aunes M, Albers GW, et al. : Risk for Major Bleeding in Patients Receiving Ticagrelor Compared With Aspirin After Transient Ischemic Attack or Acute Ischemic Stroke in the SOCRATES Study (Acute Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack Treated With Aspirin or Ticagrelor and Patient Outcomes). Circulation. 2017;136(10):907–16. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.028566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 131. Johnston SC, Amarenco P, Albers GW, et al. : Acute Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack Treated with Aspirin or Ticagrelor and Patient Outcomes (SOCRATES) trial: rationale and design. Int J Stroke. 2015;10(8):1304–8. 10.1111/ijs.12610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Wang Y, Minematsu K, Wong KS, et al. : Ticagrelor in Acute Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack in Asian Patients: From the SOCRATES Trial (Acute Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack Treated With Aspirin or Ticagrelor and Patient Outcomes). Stroke. 2017;48(1):167–73. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.014891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 133. Kamal AK, Naqvi I, Husain MR, et al. : Cilostazol versus aspirin for secondary prevention of vascular events after stroke of arterial origin. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011; (1):CD008076. 10.1002/14651858.CD008076.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI: Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(12):857–67. 10.7326/0003-4819-146-12-200706190-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 135. Zhang E, Liu T, Li Z, et al. : High CHA2DS2-VASc score predicts left atrial thrombus or spontaneous echo contrast detected by transesophageal echocardiography. Int J Cardiol. 2015;184:540–2. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.02.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Tanasa I, Arhirii R, Popa R, et al. : Echocardiography for assessment of left atrial stasis and thrombosis - three cases report. Arch Clin Cases. 2015;2(2):86–90. 10.22551/2015.06.0202.10038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Kleemann T, Becker T, Strauss M, et al. : Prevalence of left atrial thrombus and dense spontaneous echo contrast in patients with short-term atrial fibrillation < 48 hours undergoing cardioversion: value of transesophageal echocardiography to guide cardioversion. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22(12):1403–8. 10.1016/j.echo.2009.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Bernhardt P, Schmidt H, Hammerstingl C, et al. : Patients with atrial fibrillation and dense spontaneous echo contrast at high risk a prospective and serial follow-up over 12 months with transesophageal echocardiography and cerebral magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(11):1807–12. 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.11.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Vincelj J, Sokol I, Jaksić O: Prevalence and clinical significance of left atrial spontaneous echo contrast detected by transesophageal echocardiography. Echocardiography. 2002;19(4):319–24. 10.1046/j.1540-8175.2002.00319.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Goswami KC, Yadav R, Rao MB, et al. : Clinical and echocardiographic predictors of left atrial clot and spontaneous echo contrast in patients with severe rheumatic mitral stenosis: a prospective study in 200 patients by transesophageal echocardiography. Int J Cardiol. 2000;73(3):273–9. 10.1016/S0167-5273(00)00235-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Peverill RE, Gelman J, Harper RW, et al. : Stability of left atrial spontaneous echo contrast at repeat transesophageal echocardiography in patients with mitral stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79(4):516–8. 10.1016/S0002-9149(96)00800-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Irani WN, Grayburn PA, Afridi I: Prevalence of thrombus, spontaneous echo contrast, and atrial stunning in patients undergoing cardioversion of atrial flutter. A prospective study using transesophageal echocardiography. Circulation. 1997;95(4):962–6. 10.1161/01.CIR.95.4.962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Kamenský G, Drahos P, Plevová N: Left atrial spontaneous echo contrast: its prevalence and importance in patients undergoing transesophageal echocardiography and particularly those with a cerebrovascular embolic event. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1996;9(1):62–70. 10.1016/S0894-7317(96)90105-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. von der Recke G, Schmidt H, Illien S, et al. : Transesophageal contrast echocardiography distinguishes a left atrial appendage thrombus from spontaneous echo contrast. Echocardiography. 2002;19(4):343–4. 10.1046/j.1540-8175.2002.00343.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Bashir M, Asher CR, Schaffer K, et al. : Left atrial appendage spontaneous echo contrast in patients with atrial arrhythmias using integrated backscatter and transesophageal echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88(8):923–7, A9. 10.1016/S0002-9149(01)01911-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Kato H, Nakanishi M, Maekawa N, et al. : Evaluation of left atrial appendage stasis in patients with atrial fibrillation using transesophageal echocardiography with an intravenous albumin-contrast agent. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78(3):365–9. 10.1016/S0002-9149(96)00297-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Fatkin D, Feneley M: Stratification of thromboembolic risk of atrial fibrillation by transthoracic echocardiography and transesophageal echocardiography: the relative role of left atrial appendage function, mitral valve disease, and spontaneous echocardiographic contrast. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1996;39(1):57–68. 10.1016/S0033-0620(96)80041-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Appelros P: Heart failure and stroke. Stroke. 2006;37(7):1637. 10.1161/01.STR.0000227197.16951.2b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Devulapalli S, Dunlap S, Wilson N, et al. : Prevalence and clinical correlation of left ventricular systolic dysfunction in african americans with ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23(7):1965–8. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Hays AG, Sacco RL, Rundek T, et al. : Left ventricular systolic dysfunction and the risk of ischemic stroke in a multiethnic population. Stroke. 2006;37(7):1715–9. 10.1161/01.STR.0000227121.34717.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]