Abstract

A mathematico-physically valid formulation is required to infer properties of disordered protein conformations from single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer (smFRET). Conformational dimensions inferred by conventional approaches that presume a homogeneous conformational ensemble can be unphysical. When all possible—heterogeneous as well as homogeneous—conformational distributions are taken into account without prejudgment, a single value of average transfer efficiency 〈E〉 between dyes at two chain ends is generally consistent with highly diverse, multiple values of the average radius of gyration 〈Rg〉. Here we utilize unbiased conformational statistics from a coarse-grained explicit-chain model to establish a general logical framework to quantify this fundamental ambiguity in smFRET inference. As an application, we address the long-standing controversy regarding the denaturant dependence of 〈Rg〉 of unfolded proteins, focusing on Protein L as an example. Conventional smFRET inference concluded that 〈Rg〉 of unfolded Protein L is highly sensitive to [GuHCl], but data from SAXS suggested a near-constant 〈Rg〉 irrespective of [GuHCl]. Strikingly, our analysis indicates that although the reported 〈E〉 values for Protein L at [GuHCl] = 1 and 7 M are very different at 0.75 and 0.45, respectively, the Bayesian Rg2 distributions consistent with these two 〈E〉 values overlap by as much as 75%. Our findings suggest, in general, that the smFRET-SAXS discrepancy regarding unfolded protein dimensions likely arise from highly heterogeneous conformational ensembles at low or zero denaturant, and that additional experimental probes are needed to ascertain the nature of this heterogeneity.

Introduction

Single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer (smFRET) is an important, increasingly utilized experimental technique (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9) for studying protein disordered states, especially those of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) (10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15). Applications of smFRET to infer conformational dimensions of unfolded states of globular proteins (16, 17, 18) and IDPs (19, 20, 21, 22) have provided insights into fundamental protein biophysics including, for example, folding stability and cooperativity (23, 24, 25, 26, 27), transition paths (28, 29), and compactness of IDP conformations (20, 21) involved in fuzzy complexes (30, 31, 32, 33). Single-molecule conformational dimensions likely bear as well on biologically functional liquid-liquid IDP phase separation (34) because the amino acid sequence-dependent single-chain compactness of charged IDPs (35, 36, 37) are predicted by theory (38) to be closely correlated with these polyampholytic proteins’ tendency to undergo multiple-chain phase separation (39).

Basically, inference from smFRET data on measures of conformational dimensions such as radius of gyration Rg entails matching experimental average energy transfer efficiency 〈E〉exp with simulated (or analytically calculated) transfer efficiency 〈E〉sim predicted by a chosen polymer model. Using a Gaussian chain model or an augmented Sanchez mean-field theory, conventional smFRET inference procedures presume a homogeneous conformational ensemble that expands or contracts uniformly (17, 40, 41) in response to changes in solvent conditions such as denaturant concentration (42). Such an interpretation of smFRET data stipulated a significant collapse of unfolded-state conformations, as quantified by a substantial decrease in Rg, upon changing solvent conditions from strongly unfolding to folding by lowering denaturant concentration (16, 17). This smFRET prediction has led to a long-standing puzzle for Protein L (1, 43, 44, 45) because for this two-state folder (46), an apparently more direct measurement of Rg by small-angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) indicated that the average compactness of its unfolded-state conformational ensemble does not vary much with denaturant (1, 43). Similar behaviors have also been observed in SAXS experiments on other proteins (47).

Although the smFRET-SAXS puzzle remains to be fully resolved, several advances since the discrepancy was first noted (16) have contributed to clarifying the pertinent issues. A study using explicit-chain models questioned the general validity of conventional standard smFRET interpretation by showcasing that it incurs substantial errors in inferred Rg (48). A systematic analysis of subensembles of self-avoiding chains pinpointed the conventional procedure’s basic shortcoming in always presuming a homogeneous ensemble, an assumption positing particular forms of one-to-one mapping between average 〈Rg〉 and end-to-end distance 〈REE〉 that lead to grossly overestimated Rg values for small 〈E〉exp values (21). In reality, however, as should be obvious from polymer theory and explicit-chain simulations of polymers, there is no general one-to-one mapping between 〈Rg〉 and 〈REE〉 if a homogeneous ensemble is not assumed, because there are significant scatters in the Rg-REE relationship (see, e.g., Fig. 2 of (21)). Therefore, 〈REE〉 cannot be a proxy for 〈Rg〉 in general. When conformational heterogeneity is recognized, as it is clearly observed in a number of smFRET experiments (18, 20, 49), our subensemble analysis prescribes a most probable radius of gyration, Rg0, for any given 〈E〉exp (21). The same analysis shows that Rg0 can also correspond to the 〈Rg〉 of a distribution of Rg consistent with the given 〈E〉exp (Fig. 5 F of (21)). When applied to an N-terminal IDP fragment of the Cdk inhibitor Sic1 (30, 31, 33), the subensemble-inferred, denaturant-dependent Rg0 is in good agreement with SAXS-determined Rg and NMR measurement of hydrodynamic radius, in contrast to conventional procedures that produced unphysical results (21).

In line with this conceptual framework that emphasizes conformational heterogeneity and polymer-excluded volume, two other recent explicit-chain simulation studies also concluded that conventional smFRET inference of Rg is inadequate (50, 51). Notably, the coarse-grained model simulation in (50) predicted an ≈3.0 Å contraction of average Rg for Protein L upon diluting GuHCl from 7.5 to 1.0 M. The authors surmised that 3.0 Å is “close to the statistical uncertainties” of SAXS-measured Rg values, and therefore a resolution of the smFRET-SAXS discrepancy for Protein L might be within reach (50). More recently, an extensive experimental-computational study of a destabilized mutant of spectrin domain R17 and the IDP ACTR also underscored the importance of explicit-chain simulations in the interpretation of smFRET data. Denaturant-dependent expansion of conformational dimensions was consistently observed for these proteins from multiple experimental methods as well as in all-atom explicit-water MD simulations (52, 53). Protein L, however, was not the subject of this investigation.

In view of recent results that apparently affirm an appreciable denaturant-dependent Rg for unfolded proteins—albeit not as sharp as posited by conventional smFRET interpretation—is an essentially denaturant-independent unfolded-state 〈Rg〉 as envisioned in the usual picture of cooperative protein folding tenable? To address this question, we determined computationally the distribution of Rg consistent with any given 〈E〉exp and the derived probabilities that different 〈E〉exp values are consistent with the same Rg values. Taking an agnostic view as to the merits of various experimental techniques, we invoked minimal theoretical assumption so as to let experimental data speak for themselves. For simplicity, we do not consider kinetic effects in smFRET measurements (54, 55, 56). Accordingly, our coarse-grained model incorporates only the most rudimentary geometry of polypeptide chains, without any detailed force field such as those applied in recent smFRET-related simulations (48, 50, 52). By this very construction, our analysis is unaffected by any known or potential limitations of current coarse-grained and atomic force fields (14, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62). As detailed below, we found that simple conformational statistics dictates a broad distribution of Rg for most 〈E〉exp values. Among such conditional (Bayesian (63)) P(Rg|〈E〉exp) distributions for different 〈E〉exp values, large overlaps exist even for significantly different 〈E〉exp values. These results suggest that, even if published experimental data are taken at face value, conceivably the smFRET-SAXS discrepancy can be resolved provided sufficient denaturant-dependent conformational heterogeneity in the unfolded state is encoded by the amino acid sequence of the protein. Our analysis thus establishes a physical perimeter within which future experimental and theoretical smFRET analyses may proceed.

Methods

The Cα protein model and the sampling algorithm used here are the same as that in our previous study (21). The protein is represented by a sequence of n beads connected by Cα–Cα virtual bonds of length 3.8 Å. The potential energy is , where ϵθ = 10.0 kBT, θi is the virtual bond angle at bead i, θ0 = 106.3° is the reference that corresponds to the most populated virtual bond angle in the PDB (64), kB is the Boltzmann constant, T is the absolute temperature, ϵex = 1.0 kBT is the model protein’s self-avoiding excluded-volume repulsion strength, and Rij = |Rj – Ri| is the distance between beads i,j, wherein Ri is the position vector for bead i. The excluded-volume (Rhc/Rij)12 term is set to zero for Rij ≥ 10.0 Å. As in many protein folding simulations (25), we use a hard-core repulsion distance Rhc = 4.0 Å for most of the analysis presented below, although some results for Rhc = 3.14 or 5.0 Å (21) are also utilized to assess the robustness of our conclusions.

We conducted Monte Carlo sampling by applying the Metropolis criterion (65) at T = 300 K using an algorithm described previously (66) that assigns equal a priori probability for pivot and kink jumps (67, 68). The acceptance rate for the attempted chain moves was ≈30%. The first 107 equilibrating attempted moves of each simulation were excluded from the tabulation of statistics. Subsequently, 109 moves were attempted for each chain length n we studied to sample 107 conformations for further analysis. Values of radius of gyration (where ) and end-to-end distance REE = |Rn – R1| were computed for the sampled conformations to determine the distribution P(Rg, REE) of populations centered at various (Rg, REE) with only narrow ranges of variations (bins) around the given Rg and REE values.

We focus here only on cases in which the dyes are attached to the two ends of the protein chain. FRET efficiency for a given conformation in the model with end-to-end distance REE is then calculated by the formula,

| (1) |

where R0 is the Förster radius of the dye. Based on the values of R0 = 54 ± 3 Å given by Sherman and Haran (16) and R0 = 54 Å provided by Merchant et al. (17) for the Alexa 488 and Alexa 594 dyes employed in their Protein L experiments, we set R0 = 55 Å in most of the computation for Protein L below. For any given distribution P(REE), the average FRET efficiency is given by . The subscripts in the above expressions 〈E〉exp and 〈E〉sim are omitted hereafter for notational simplicity when the meaning of the average 〈E〉 is clear from the textual context. Protein L is a 64-residue α/β protein. To account for the added effective chain length due to the two dye linkers, we used n = 75 chains to model the unfolded-state conformations of Protein L. This prescription for the linkers is similar to the ten (69) or eight (17) extra residues used before. In addition to the exemplary computation for Protein L, simulations were also conducted for several other representative chain lengths (n = 50, 100, 125, and 150) and Förster radii (R0 = 50, 60, and 70 Å) for future applications to other disordered protein conformational ensembles.

Results

Physicality of a subensemble approach to smFRET inference

To ensure that smFRET inference takes into account only physically realizable conformations, we recently introduced a systematic methodology to infer a most probable radius of gyration Rg0 from an experimental 〈E〉exp by considering subensembles of self-avoiding walk (SAW) conformations with narrow ranges of Rg simulated using an explicit-chain model. For any such range (bin) centered around an Rg, the method provides a conditional distribution P(REE|Rg) for the end-to-end distance REE. An average FRET efficiency is then calculated. The most probable Rg0 is determined by matching 〈E〉exp with 〈E〉(Rg), that is, by solving

| (2) |

for Rg0 to arrive at Rg0(〈E〉) (wherein the “exp” is dropped from the average), which is the inverse function of 〈E〉(Rg). As documented before (18, 21) and outlined above, by explicitly allowing for unfolded-state conformational heterogeneity—which is expected physically (14, 15)—the subensemble SAW method circumvents the limitations of conventional smFRET inferences that presuppose a homogeneous conformational ensemble (16, 17, 41).

Based on the same conceptual framework, here we approach the question of smFRET inference from a complementary angle. Instead of starting from subensembles with a narrow range of Rg to derive P(REE|Rg), then 〈E〉(Rg0) and Rg0(〈E〉), here we start from subensembles with a narrow range of REE (smallest bin size Å, see below), and hence a narrow variation of E (i.e., via Eq. 1; the E values in a narrow range may be taken as a single E value), to derive distribution P(Rg|REE) conditioned upon REE. Whereas P(Rg|REE) is related to P(REE|Rg) by Bayes’ theorem, P(Rg|REE) is of interest because it quantifies directly the possible variation in conformational dimensions when only a single 〈E〉exp value is known. This is because for every single FRET efficiency E, the quantity P(Rg|REE) is sufficient to provide the conditional distribution P(Rg|E). Then, based on these derived P(Rg|E) distributions for all individual E values, the P(Rg|〈E〉exp) distribution conditioned upon any value of 〈E〉exp averaged from any underlying distribution P(E) of E can be readily obtained.

Estimation of conformational dimensions from FRET efficiency is highly model dependent because of insufficient structural constraint

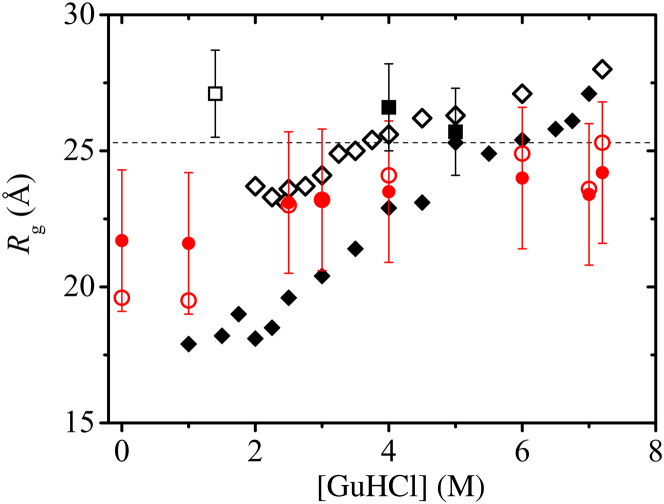

As an exemplary case, we applied this formulation to Protein L. Fig. 1 shows considerable discrepancies between SAXS- (squares) and smFRET-deduced (diamonds) 〈Rg〉 values, and that different smFRET inference approaches lead to very different pictures of how 〈Rg〉 of this protein varies with denaturant concentration. For a change in [GuHCl] from ≈7 to ≈2 M, conventional inference (diamonds) yielded large 〈Rg〉 decreases of ≈9 Å (solid diamonds, (16)) or ≈5 Å (open diamonds, (17)). In contrast, subensemble SAW methods (circles) stipulate a much milder variation with respect to [GuHCl]. For the same [GuHCl] change, the most probable Rg0 value decreases by ≈2 Å (open circles) whereas the change in root-mean-square conditioned upon the published experimental 〈E〉exp data is even smaller: it decreases by ≈1 Å (solid circles). When [GuHCl] is reduced further from 2 to 0 M, the total decrease over the entire [GuHCl] range is ≈5.5 Å for Rg0 but merely ≈2 Å for . We computed distributions of Rg2 and here because these quantities are determined by SAXS (47, 70). Our results are essentially unchanged if 〈Rg〉 is considered instead (see below).

Figure 1.

Unfolded-state dimensions of Protein L obtained from SAXS and various interpretations of smFRET experiments. Open and solid squares are results from previous time-resolved and equilibrium SAXS experiments by Plaxco et al. (46) at 2.7 ± 0.5° and 5 ± 1°C, respectively. The associated error bars represent 1 SD fitting uncertainties (kinetic data) or confidence intervals from two to three independent measurements (thermodynamic data). Subsequent equilibrium SAXS measurement at 22°C by Yoo et al. (43) produced essentially identical results. Open and solid diamonds are results from smFRET experiments, respectively, by Merchant et al. (17) (Eaton group, temperature not provided) and by Sherman and Haran conducted at “room temperature” (16). These prior experimental data were compared in a similar manner in (43). Here, the open and solid circles are from our analysis corresponding, respectively, to the most-probable Rg0 (21) and the root-mean-square value based on the experimental transfer efficiency 〈E〉 = 0.74 for [GuHCl] = 0 given by Merchant et al. (17), the 〈E〉 values for Protein L (corrected from the measured FRET efficiency 〈Em〉) in SI Table 2 for the same reference, and the 〈E〉 values for [GuHCl] = 1 and 7 M in Sherman and Haran (16). A Förster radius of R0 = 55 Å was used in our calculations. The error bars for the solid circles span ranges delimited by , where σ(Rg2) is the SD of the distribution of Rg2 at the given E value. The horizontal dashed line marks the Rg = 25.3 Å value we obtained from applying the scaling relation of Kohn et al. (71) to N = 74, where n = N + 1 = 75 is taken to be the equivalent number of amino acid residues for Protein L plus dye linkers. To see this figure in color, go online.

For every 〈E〉exp data point we considered for Protein L using subensemble analysis, significant diversity in Rg2 values that are nonetheless consistent with the given 〈E〉exp is observed (Fig. 1, error bars for solid circles). In other words, this method can infer the full Bayesian distribution of Rg2 for a given 〈E〉exp and hence a rigorous error bar can be provided (whereas error bars are not provided for Rg0 because it represents a narrow range of Rg values that lead to a distribution of E values, which in turn average to an 〈E〉 (21)). Fig. 1 shows clearly that the large variations in inferred Rg2 values and the large overlaps of the ranges of these variations at different [GuHCl] values imply that significant fractions of the unfolded conformational ensembles of Protein L at different [GuHCl] values can encompass conformations with very similar Rg values. Notably, the average Rg expected of a fully unfolded protein in good solvent of the same length as Protein L with dye linkers (horizontal dashed line, (71)) is within the error bars for [GuHCl] as low as 3 M. Even at zero denaturant, the Rg ≈ 24.5 Å value (upper error bar), at 1 SD from the mean, , is only ≈1 Å from the average Rg expected of a fully unfolded conformational ensemble.

Conformations consistent with a given FRET efficiency generally have highly diverse radii of gyration

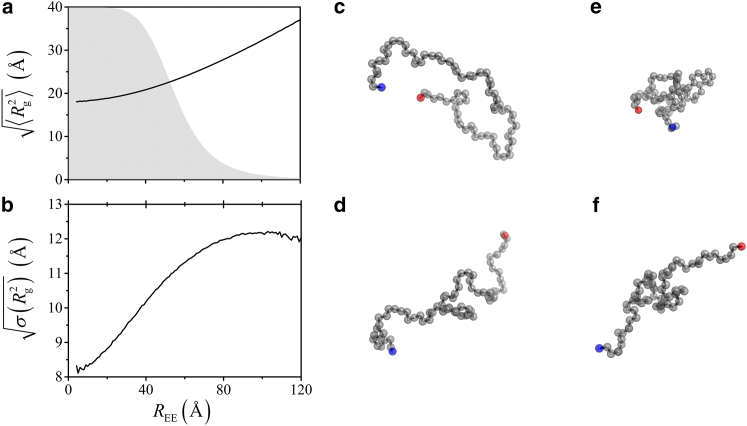

The diversity in Rg values that are consistent with a given REE (and therefore a given 〈E〉) is further illustrated in Fig. 2. For our Protein L model, the square root of the SD in Rg2, , is substantial for the entire range of REE: it increases steadily from ≈8 Å for REE ≈ 0 to ≈12 Å for REE ≈ 120 Å (Fig. 2 b). Therefore, although of the conformations consistent with a given REE increases monotonically from ≈18 to ≈37 Å over the REE range in Fig. 2 a, knowledge of REE alone can barely narrow down the wide range of possible Rg values and vice versa (Fig. 2, c–f).

Figure 2.

Large variations in dimensions among conformations with a given end-to-end distance REE. (a) Root-mean-square and (b) the square root of the SD of Rg2 as functions of REE. The gray profile in (a) shows the theoretical transfer efficiency Eq. 1 for n = 75 and R0 = 55 Å in a vertical scale ranging from zero to unity. (c–f) Example conformations with the darker shaded (red and blue online) beads marking the termini of n = 75 chains. They serve to illustrate the possible concomitant occurrences of (c) small REE = 19.7 Å and large Rg = 26.3 Å; (d) large REE = 80.1 Å and large Rg = 26.2 Å; (e) small REE = 19.7 Å and small Rg = 14.2 Å; and (f) large REE = 80.4 Å and small Rg =19.8 Å. These examples underscore that there is no general one-to-one mapping from 〈REE〉 to 〈Rg〉. To see this figure in color, go online.

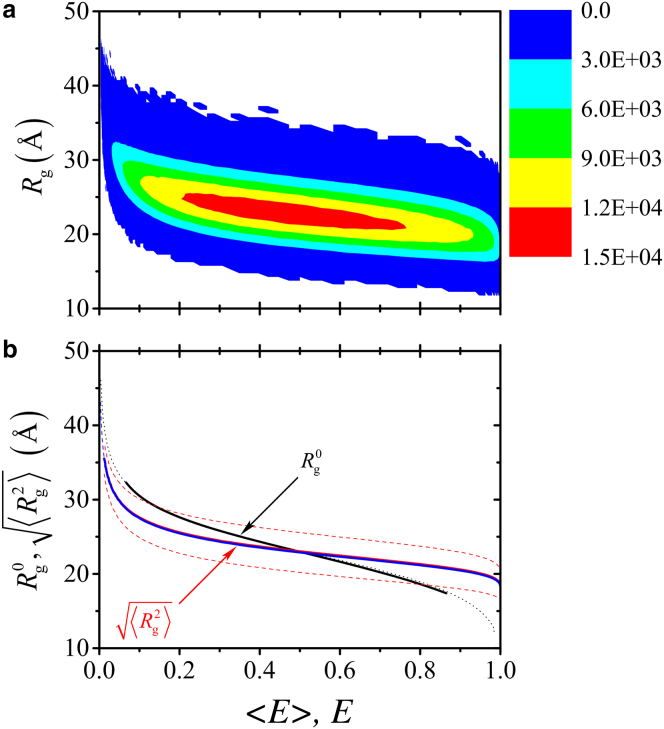

A panoramic view of the logic of smFRET inference on conformational dimensions is provided by Fig. 3, wherein P(Rg, REE) is converted to P(Rg, E) by Eq. 1. Using our model for unfolded Protein L as an example, the landscape in Fig. 3 a shows clearly that the Rg–E scatter is wide, with the most populated (red) region elongated mainly along the E axis with a small negative incline. Consistent with Fig. 1, this population distribution implies that even large variations in E do not necessitate much change in the Rg distribution. This feature of the Rg–E space is demonstrated more specifically by the curve in Fig. 3 b (red solid curve; the dependence of 〈Rg〉 on E is essentially identical, blue solid curve), wherein an overwhelming majority of the E values are seen to be consistent with Rg values between 20 and 27 Å that are within 1 SD of (red dashed curves). In contrast, conventional smFRET inference procedures—which are demonstrably unphysical in some situations (21)—posit a much more sensitive dependence of inferred 〈Rg〉 on 〈E〉 (Fig. S1). It is noteworthy that, for most E values, the variation of is milder than that of Rg0(〈E〉); i.e., . In fact, this trend is already evident in Fig. 1 from the milder [GuHCl] dependence of (solid circles) than that of Rg0 (open circles).

Figure 3.

Perimeters of inference on conformational dimensions from Förster transfer efficiency. (a) Distribution P(Rg, E) of conformational population as a function of Rg and E for n = 75 and R0 = 55 Å. The distribution was computed using REE × Rg bins of 1.0 Å × 0.5 Å. White area indicate bins with no sampled population. (b) Shown here is the most-probable radius of gyration Rg0(〈E〉) from our previous subensemble SAW analysis (21) (black solid curve) compared against root-mean-square radius of gyration (red solid curve) computed by considering 30 subensembles with narrow ranges of REE. The latter overlaps almost completely with 〈Rg〉(E) computed using the same set of subensembles (blue solid curve). Another set of Rg0 (〈E〉) values (black dotted curve) and another set of 〈Rg〉(E) values (blue dashed curve) were obtained from the distribution in (a), respectively, by averaging over E at given Rg values and by averaging over Rg at given E values. Variation of radius of gyration is illustrated by the red dashed curves for as functions of E. The essential coincidence between the black solid and dotted curves and between the blue solid and dashed curves indicate that these results are robust with respect to the choices of bin size we have made. Note that the black solid curve for Rg0(〈E〉) does not cover 〈E〉 values close to zero or close to unity because larger Rg bin sizes (∼1.1–3.6 Å) than the current Rg bin size of 0.5 Å were used (Table S5 of (21)), thus precluding extreme values of 〈E〉 to be considered in that previous n = 75 subensemble SAW analysis (21). This limitation is now rectified for n = 75 (black dotted curve).

Conformations sharing similar radii of gyration can have very different FRET efficiencies

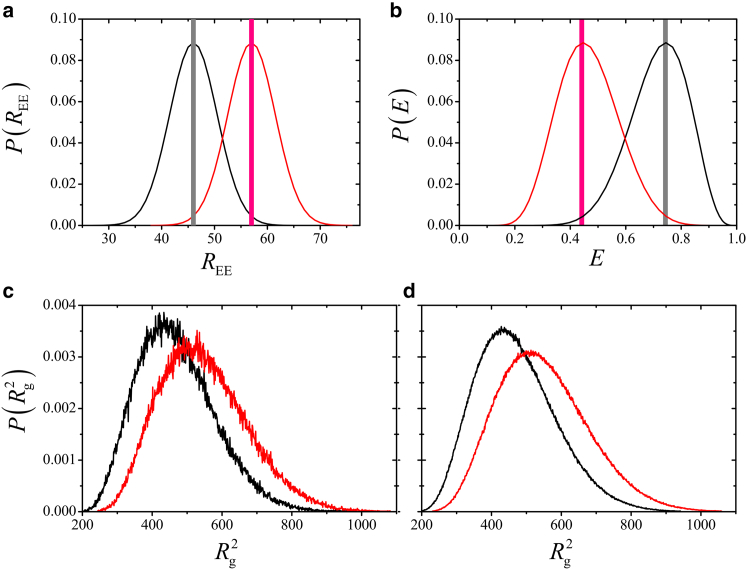

In light of the large diversity in Rg values conditioned upon a given E and the very mild variation of and σ(Rg2) with E (Fig. 3), one expects that conformations consistent with even very different E values share highly overlapping Rg values. We now characterize this overlap quantitatively by first considering two sharply defined representative REE values in Fig. 4 a (vertical bars depicting δ-function-like distributions) that correspond, by virtue of Eq. 1, to two sharply defined E values ≈0.45 and 0.75 (Fig. 4 b). These E values are representative because they coincide with the experimental 〈E〉exp for Protein L at [GuHCl] = 7 and 1 M, respectively (16). The conditional distributions P(Rg2|E) for E = 0.45 and 0.75 overlap significantly, with the overlapping area ≈0.75 (Fig. 4 c). By definition, this area is the overlapping coefficient (OVL), used in statistical analysis for measuring similarity between distributions (72). OVL between two distributions is generally given by

| (3) |

where P1(x) and P2(x) are two normalized distributions of variable x. The P1, P2 distributions are P(Rg2|E = 0.45) and P(Rg2|E = 0.75) in Fig. 4 c.

Figure 4.

Substantially overlapping distributions of conformational dimensions can be consistent with very different Förster transfer efficiencies. (a) Given here are hypothetical distributions P(REE) of end-to-end distance REE. Two hypothetical sharp distributions at two REE values (vertical bars) and two hypothetical broad Gaussian distributions (bell curves) are centered at these two REE values, with SD of the Gaussian distributions chosen to be 20.3 Å. (b) Given here is the corresponding distribution P(E) of Förster transfer efficiency E. The left and right sharp distributions of P(REE) in (a) lead, respectively, to E ≈ 0.745 (right) and E ≈ 0.447 (left) in (b). The corresponding P(E) for the hypothetical Gaussian distributions in (a) entail broad distributions in E in (b) with mean values at 〈E〉 = 0.735 (right) and 〈E〉 = 0.453 (left), respectively. (c) The left and right curves are the conditional distributions P(Rg2|E), respectively, for the sharply defined E ≈ 0.745 and E ≈ 0.447 in (b). (d) Similar to (c) except the distributions of Rg2 are now for the two broad P(E) distributions in (b). We denote these distributions as P(Rg2|〈E〉). The Rg2 bin size in (c and d) is 1.0 Å2. The OVL of the two normalized distribution curves in (c and d) are, respectively, 0.747 and 0.754. The percentages of population with Rg2 ≥ 625 Å in the distributions in (c and d) are, respectively, 9.2 and 10.1% for E ≈ 0.745 and 〈E〉 = 0.735, and 25.2 and 26.3% for E ≈ 0.447 and 〈E〉 = 0.453. To see this figure in color, go online.

Because experimentally determined E values are often averages, not sharply defined (16, 17), it is necessary to address more realistic distributions of E on smFRET inference. We do so here by considering hypothetical broad Gaussian distributions for REE centered around the two sharply defined REE values (Fig. 4 a, curves, SD σ (REE) = 20.3 Å), resulting in broad distributions in E averaging to E = 0.45 and 0.74 Fig. 4 b, curves), which are essentially equal to the sharply defined E values of 0.45 and 0.75. Modifying the two sharply defined E values to two broad distributions of E has very little impact on either the individual Rg2 distributions [P(Rg2|〈E〉)] or the overlap of the two P(Rg2|〈E〉) distributions (Fig. 4 d). The overlapping coefficient remains ≈0.75.

Although the distributions in Fig. 4, c and d, are very similar, there is a basic difference between two sharply defined E values and two broad distributions of E in regard to the conformations in the Rg2 distributions. When the E values are sharply defined, there is no overlap in the actual conformations in the two P(Rg2|E) distributions because the conformational ensembles consistent with two sharply defined REE values are disjoint. However, when the two sets of E values are broadly distributed with overlapping REE and E values (Fig. 4, a and b, curves), some of the conformations from the two different Rg2 distributions that contribute to the overlapping region in Fig. 4 d can be identical.

The distribution of radius of gyration consistent with a given single FRET efficiency is very similar to that consistent with a symmetric distribution of FRET efficiencies centered around it

This insensitivity of the distribution of Rg2 (and therefore also of Rg) conditioned upon given E values to variations in the width of Gaussian-like distribution of E is not difficult to fathom. Given the mild variation of and σ (Rg2) with respect to E (Fig. 3 b) and the tendency for effects from E values on opposite sides of the average of a symmetric distribution to cancel each other, averaging over a range of E values centered around a given E (= 〈E〉) is not expected to result in an overall average Rg2 and an overall distribution width that are substantially different from those for a sharply defined E = 〈E〉. For the sake of testing the robustness of this insensitivity, here we have used a large SD, σ(REE), for the hypothetical Gaussian distributions in Fig. 4 a. This σ(REE) is equal to the SD of the REE distribution for the full conformational ensemble (with the mean, 〈REE〉 = 59.1 Å). Beside the REE and E distributions in Fig. 4, we performed additional calculations using Gaussian distributions of REE centered at different averages, with different SDs that equal 0.1×, 0.25×, 0.5×, and 0.75× σ(REE). These constructs beget distributions of E with different values. In all cases we considered, the resulting Rg2 distribution for the given 〈E〉 is essentially the same across the different SDs as well as for the case with a sharply defined E = 〈E〉. This finding suggests that the – E dependence in Fig. 3 b is not strictly limited to sharply defined E values. An essentially identical relationship should also be is applicable to the and associated σ (Rg2) values conditioned upon reasonably symmetric distributions of E with mean value 〈E〉. In other words, in Fig. 3, which was originally constructed for sharply defined E values, is also expected to be a good approximation of for essentially symmetric distributions of E. More generally, the for any distribution P(E) of E, symmetric or otherwise, can be calculated readily as by using the 〈Rg2〉(E) values from Fig. 3.

Inference of conformational dimensions solely from FRET efficiency can entail significant ambiguity

To ascertain more generally the degree to which the Rg values consistent with different FRET efficiencies overlap, we extended the comparison in Fig. 4 c for two E values by computing the corresponding overlapping coefficients (Eq. 3) for all possible pairs of FRET efficiencies, E1 and E2:

| (4) |

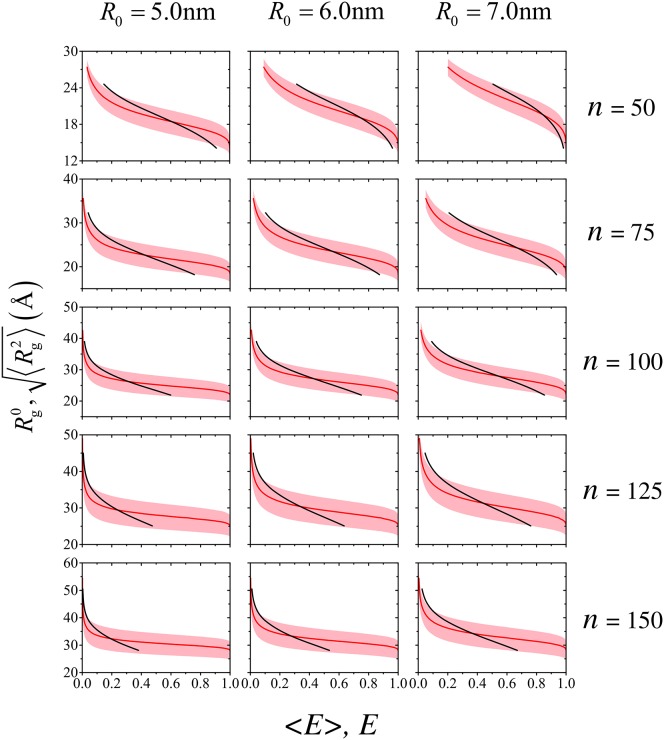

The heat map in Fig. 5 indicates substantial overlaps for a majority of (E1, E2). Among all possible (E1, E2) combinations, >30% have OVL ≥ 0.8, and close to 60% have OVL ≥ 0.6 (Fig. S2 a), meaning that their P(Rg2|E) distributions are quite similar. Notably, OVL increases significantly as E1, E2 increase above ≈0.4. We also computed averages of Rg2 over the overlapping regime of the pairs of distributions. These averages represent conformational dimensions that are consistent with both E1 and E2. In a majority of the situations, the root-mean-square Rg2 for the overlapping regime stays within a relative narrow range of ≈22–25 Å for our model of unfolded Protein L, even for E1 and E2 that are quite far apart (Fig. S2 b). Therefore, taken together with Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4, the overview in Fig. 5 indicates that when an explicit-chain physical model is used to interpret/rationalize smFRET data (18, 21), as is the case here, the a priori expectation is that even substantial changes in 〈E〉exp do not necessarily imply large changes in average Rg. In this light, previous smFRET-based stipulations of large denaturant-dependent changes in the 〈Rg2〉 of Protein L (16, 17) are demonstrably inconclusive in the absence of additional relevant experimental information, because they were based on conventional inference approaches that are not entirely physical (21). Moreover, as is evident from the examples in Fig. 6, the trend of a mild Rg–E variation that we saw previously (21) and in Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 here, which is derived directly from explicit-chain polymer models, is expected to hold generally for other FRET systems of disordered proteins with different chain lengths and Förster radii as well.

Figure 5.

Ambiguities in FRET inference of conformational dimensions. The heat map provides for n = 75 and R0 = 55 Å the overlapping coefficient of pairs of Rg2 distributions conditioned upon FRET efficiencies E1 and E2. Contours on the heat map are for = 0.8, 0.6, 0.4, and 0.2, as indicated by the scale on the right. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 6.

Most probable and root-mean-square radius of gyration. Shown here is generalization of the Rg0(〈E〉) (solid black curve traversing across the shaded region in each panel at a steeper incline), and (curve at a milder incline in the middle of the shaded region in each panel) for R0 = 55 Å and n = 75 in Fig. 3 to other Förster radii R0 and chain lengths n. The shaded areas are bound by , which were represented by red dashed curves in Fig. 3. As discussed in the text, the curves computed here for sharply defined E values are expected to apply also to for essentially symmetric distributions of E where 〈E〉 denotes the mean value of E in such distributions. As pointed out above for Fig. 3, the black Rg0(〈E〉) curves shown here do not cover 〈E〉 values close to zero or unity because of the relatively large Rg bin sizes used previously (21). To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

Subensemble-derived conditional distributions of Rg are basic to smFRET inference

To recapitulate, here we have further developed the subensemble SAW approach to smFRET inference of conformational dimensions (21), which is based on the obvious principle that only physically realizable conformational ensembles should be invoked to interpret smFRET data. We focused previously on the most probable radius of gyration Rg0(〈E〉), which is derived from distributions of E conditioned upon a narrow range of Rg. Here we have considered the complementary quantity, , which is the root-mean-square value of Rg conditioned upon a given E. These quantities are not identical, but their variations with 〈E〉 or E are similar (Figs. 3 and 6). Relative to conventional approaches to smFRET inference, both Rg0(〈E〉) and exhibit a milder dependence on smFRET efficiency, covering a range of Rg values consistent with polymer physics (21). By construction, Rg0(〈E〉) is appropriate if it is known or presumed that the disordered conformations populate a narrow range of Rg values or distribute symmetrically around an average Rg (21), whereas is suitable when such knowledge or assumption is absent. Therefore, it is our contention that, given a single 〈E〉exp in the absence of additional experimental data, the quantity should serve well as the physically valid Bayesian inference. However, if the Rg values are known experimentally to be confined to a narrow range, which may be the case for certain IDPs, Rg0(〈E〉) would be the valid inference when no further information besides 〈E〉exp and the confinement is available. The data provided in Fig. 6 and the Supporting Information of (21) as well as those in the present Figs. 3 and 6 are useful for this purpose.

Physically valid interpretation of smFRET data requires explicit-chain modeling

Conventional approaches to smFRET inference neglects possible sequence-dependent conformational heterogeneity of unfolded ensembles. They always enforce a full conformational ensemble that expands or contracts homogeneously (16, 17). Lacking an explicit-chain representation, this elementary unphysicality of conventional smFRET inference was often overlooked. Consequently, when 〈E〉exp is small, these procedures force the entire ensemble to expand, leading to unrealistically high inferred 〈Rg〉 values (21). Although conformations with large REE (and hence small E or 〈E〉) and large Rg are part of our subensemble analysis (e.g., Fig. 2 f), these rare conformations in our simulations did not arise from physically unrealistic long Kuhn lengths or unrealistic intrachain repulsion as in conventional approaches (21). This is the fundamental reason why conventionally inferred 〈Rg〉 values differ from those simulated using physical, explicit-chain models (18, 21, 48, 50, 51), and that such simulations, for Sic1 (21) and Protein L (50), for example, produced smaller variations in 〈Rg〉 consistent with the limits prescribed by our subensemble SAW analysis (21) (Fig. S1).

In this perspective, recent computational investigations using explicit-chain simulations to rationalize smFRET data represent significant advances. These efforts include a study on Protein L using a denaturant-dependent construct based on a native-centric Gō-like side-chain potential (50) and an all-atom, explicit-water MD study on ACTR and an R17 variant (52, 53). In these studies, the conformational heterogeneity of unfolded/disordered ensembles encoded by amino acid sequences is taken into account either by a structure-specific Gō-like potential (50) or a transferrable atomic force field (52, 53). However, it should be emphasized that commonly used force fields may not capture the high degrees of folding cooperativity observed for real proteins (25). In particular, in comparison with experiment, the disordered conformational ensembles predicted by several atomic force fields are too compact (26, 57, 59, 73). Efforts to address this shortcoming are underway (60, 61, 62). For the case of Protein L, an earlier study (58) using a denaturant-dependent coarse-grained side-chain model similar to the one used in the recent study by Maity and Reddy (50) suggests that, even with an essentially native-centric potential, the model is insufficiently cooperative in comparison with experiment. Specifically, the predicted chevron plot for Protein L has a folding-arm rollover (58), which is absent in experiment (46). This behavior is related to denaturant-dependent shifts in the positions of transition and unfolded states in the model (58), which would likely lead to a reduction in 〈Rg〉 with decreasing [GuHCl]. We view these known limitations of current potentials for protein folding simulation as part of the very puzzle underscored by the smFRET-SAXS discrepancy. The crux of the matter is, if the degrees of folding cooperativity for some—albeit not all—proteins, such as Protein L, are indeed as high as envisioned by SAXS measurements (46), why are common force fields unable to capture the phenomenon (58)?

In lieu of attempting to provide an accurate model of sequence-specific interactions, our subensemble SAW approach to smFRET inference does not presume any particular model of sequence-dependent conformational heterogeneity. By itself, our approach merely establishes a perimeter for physically realizable conformational variation (21). The rationale is to let experiment take precedence in uncovering the actual conformational heterogeneity. In other words, P(Rg2|E) is a baseline distribution upon which any reweighting of conformational population by sequence-specific effects is to be considered without prejudgment. Under this conceptual framework, we make no generalization as to whether conformational dimensions of disordered proteins would or would not increase with increasing denaturant concentration. Such a verdict has to be made on a case-by-case basis depending on the nature of available experimental information in addition to the limited structural constraint provided by smFRET. For example, our previous study indicates that the dimensions of IDP Sic1 increase when [GuHCl] is increased from 1 to 5 M (21). A more recent in-depth study using smFRET, SAXS as well as other experimental probes and computation has demonstrated convincingly that conformational dimensions of the IDP ACTR and a destabilized mutant of globular protein R17 increase upon increasing [GuHCl] or [urea] (52, 53). It is of relevance, however, that unlike Protein L (46), R17 is not a two-state folder as its chevron plot has a nonlinear unfolding arm (74).

A hypothetical scenario for the case of Protein L

To make conceptual progress toward understanding the Protein L unfolded state, we first put aside potential experimental artifacts that might be caused, for example, by the sensitivity of Rg to the fitting range of the Guinier analysis and the difficulty in obtaining low-denaturant SAXS data (53). For the following consideration, we assume that the SAXS finding of an essentially denaturant-independent 〈Rg〉 ≈ 25 Å (46) and the smFRET data of a decreasing 〈E〉exp with increasing denaturant (16, 17) are both valid. We then seek to rationalize the experimental data by constructing denaturant-dependent heterogeneous conformational ensembles consistent with both sets of data. In so doing, we are merely following an investigative logic commonly practiced in the construction of putative unfolded and IDP ensembles (53, 75, 76, 77). As explained below, a solution to the smFRET-SAXS puzzle is possible if, with decreasing denaturant, sequence-specific effects become increasingly biased to redistribute conformational population to high Rg2 values such that a nearly constant is maintained despite the shift of the baseline Bayesian distribution P(Rg2|〈E〉) to lower Rg2 values due to increasing 〈E〉exp with decreasing denaturant (Fig. 4).

How biased does such a denaturant-dependent conformational heterogeneity need to be? Using the example in Fig. 4 for unfolded Protein L at [GuHCl] = 1 and 7 M, an estimate of the necessary denaturant-dependent bias needed to resolve the smFRET-SAXS puzzle can be made. Consider the Bayesian distributions P(Rg2|E) (Fig. 4 c) and P(Rg2|〈E〉) (Fig. 4 d). These are baseline distributions that do not account for any sequence-specific effect. They show that ≈10% and ≈25%, respectively, of the E,〈E〉exp ≈ 0.74 and E,〈E〉exp ≈ 0.45 populations have Rg ≥ 25 Å (Rg2 ≥ 625 Å2). This means that different subsets of these two conformational distributions can have the SAXS-observed . Indeed, possible sequence-specific reweighted distributions for Protein L that are consistent with both smFRET and SAXS may take the forms of the shaded symmetric regions in Fig. 7 (gray, and pink plus gray areas). These distributions are consistent with smFRET and SAXS because they both have (thus consistent with SAXS), yet 〈E〉 ≈ 0.74 (〈E〉exp at [GuHCl] = 1 M) for the gray distribution and 〈E〉 ≈ 0.45 (〈E〉exp at [GuHCl] = 7 M) for the pink-plus-gray distribution.

Figure 7.

A hypothetical resolution of the Protein L smFRET-SAXS puzzle. The two distributions depicted by the black and red curves are from Fig. 4d, for 〈E〉 = 0.74 and 〈E〉 = 0.45, respectively. For Rg2 ≥ 625 Å, the area shaded in pink is under the 〈E〉 = 0.45 (red) distribution but above the (black) distribution, whereas the area shaded in gray is under the 〈E〉 = 0.74 (black) distribution. The Rg2 < 625 Å areas that are in lighter shades are mirror reflections of the corresponding Rg2 ≥ 625 Å areas with respect to Rg2 = 625 Å. The sum total of the pink-plus-gray area (∼50% of P(Rg2|〈E〉 = 0.45)) represents a hypothetical ensemble with 〈E〉 ≈ 0.45 and Å, whereas the gray area (∼20% of P(Rg2|〈E〉 = 0.74)) represents a hypothetical ensemble with 〈E〉 ≈ 0.74 but nonetheless the same Å. Shown on the right are example conformations in these restricted ensembles, as marked by the arrows. Both conformations have Rg2 = 700 Å2 (Rg = 26.5 Å), but their different REE values entail different E values of (top) and (bottom). See text and Fig. 4 for further details.

That this holds true is easy to see if the distributions in question are for two sharply defined E values. In that case, we use the two P(Rg2|E) values in Fig. 4 c to define two restricted (unnormalized) distributions Pr(Rg2|E) such that Pr(Rg2|E) = P(Rg2|E) for Rg2 < 625 Å2 and Pr(Rg2|E) = min for Rg2 < 625 Å2. Because of the mirror symmetry of these distributions with respect to Rg2 = 625 Å, the values of their are both ≈25 Å, even though E = 0.447 for all conformations in the Pr(Rg2|E = 0.45) distribution and E = 0.745 for all conformations in the Pr(Rg2|E = 0.75) distribution. This result is generalizable to the two broad P(E) distributions in Fig. 4 b. Consider . By definition, this integral gives exactly the Rg2 ≥ 625 Å2 parts (in darker shades) of the gray, and pink-plus-gray areas in Fig. 7 because Pr(Rg2|E) = P(Rg2|E) for Rg2 ≥ 625 Å2 and . The integral yields close approximations to the Rg2 < 625 Å2 lighter-shaded areas in Fig. 7 because varies mildly in the range 0.2 ≤ E ≤ 0.95 (Fig. 3 b) that covers most of the P(E) distributions (Fig. 4 b). This procedure ensures that the conformational populations represented by the gray-plus-pink and gray areas in Fig. 7 preserve their respective values because preserves the average E at every Rg2. Therefore, the shaded distributions in Fig. 7 represent conformations with different 〈E〉 ≈ 0.45 and 〈E〉 ≈ 0.74 but possess the same . This hypothetical scenario indicates that consistency between SAXS and smFRET is possible if sequence-induced heterogeneity entails a mild restriction to ∼2 × 25% = 50% of the conformational possibilities allowed by the 〈E〉exp at [GuHCl] = 7 M, but imposes a more severe restriction to ∼2 × 10% = 20% of the conformational possibilities allowed by the 〈E〉exp at [GuHCl] = 1 M (Fig. 7). It should be emphasized, however, that this is only one among many possible scenarios of denaturant-dependent conformational reweighting that can satisfy both smFRET and SAXS data. Further information about the reweighting may be offered by additional experimental data such as pair distributions from SAXS, but that is beyond the scope of this work.

The denaturant-dependent biases represented by the above estimates are intuitively plausible because the required biases of 50% → 20% for [GuHCl] = 7 M → 1 M are not excessive. These fractional restrictions are only rough estimates, but they serve to illustrate a key concept. It is conceivable that the required restrictions can be less. For instance, when the atomic size and shapes of amino acid side chains are taken into account, the actual intraprotein excluded volume effect can be stronger than that embodied by the Rhc = 4 Å repulsion distance in the Cα model. If Å is used instead (21), the Rg distribution would shift upward by ≈1–3 Å (Fig. S3). In that case, the fractions of P(Rg2|〈E〉) with Rg ≥ 25 Å would increase, enabling significantly less denaturant-dependent biases of 81% → 43% (for [GuHCl] = 7 M → 1 M) to resolve the smFRET-SAXS discrepancy (Fig. S4).

Conclusions

We deem this scenario for Protein L viable pending further experiment because natural proteins are heteropolymers, not homopolymers. Their amino acid sequences encode for heterogeneous intrachain interactions, especially under strongly folding (low or zero denaturant) conditions, which logically can only lead to heterogeneous conformational ensembles even when the chains are disordered. Unfolded conformations are not Gaussian chains (78). The question is not whether heterogeneity exists but the degree of heterogeneity and its impact. Such heterogeneity is observable by NMR (79), in some cases even in high urea concentrations (80, 81), not only for proteins such as BBL that do not fold cooperatively (82), but also for two-state folders (as defined by an approximate equality of van’ t Hoff and calorimetric enthalpies of unfolding, and chevron plots with linear folding and unfolding arms (25, 83)) such as cytochrome c (84). The biophysics of protein folding processes that are macroscopically cooperative yet microscopically heterogeneous is readily understood theoretically (85, 86, 87). From a mathematical standpoint, it is definitely possible, as we envisioned above, for heterogeneous conformational ensembles that are distinct from random coils or SAWs to have overall random-coil or SAW dimensions nonetheless (21), as has been demonstrated by a recent study of the IDP Ash1 (88) and by hypothetical explicit-chain ensembles constructed to embody such properties (89, 90). The scenario we suggested for resolving the smFRET-SAXS discrepancy for Protein L posits an increased population of transient looplike disordered conformations with the two chain termini close to each other under native conditions. Is this feasible? Of relevance to this question is the experimental finding that conformations with enhanced populations of nonlocal contacts are involved in the folding kinetics of adenylate kinase (91, 92, 93). Conformations with similar properties have also been suggested by theory to be favored along folding transition paths (29). Recently, a disordered conformational state with such properties was identified for the protein drkN SH3 as well, though in this case it is induced by high rather than by low denaturant (18). All in all, it is clear from the above considerations that denaturant-dependent heterogeneity in disordered protein conformational ensembles is expected in general. To what degree and in what manner it may account for the smFRET-SAXS discrepancy will have to be ascertained by further experiment.

Recently, Fuertes et al. (94) make an observation similar to ours—among other results of theirs—that the smFRET-SAXS puzzle may be resolved by recognizing that a given REE can be consistent with a variety of Rg values. For the record, it is noted that one of the authors of this work (94) kindly sent their manuscript (submitted but unpublished at the time) to us after we shared with him our article on May 15, 2017 before submitting the original version of this article to this journal and making it publicly available on arXiv.org (arXiv:1705.06010).

Author Contributions

J.S. and H.S.C. designed the research. J.S., G.-N.G., and H.S.C. performed the research. J.S., G.-N.G., C.C.G., and H.S.C. analyzed the data. T.S. contributed computational tools. J.S. and H.S.C. wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

H.S.C. thanks Osman Bilsel, Kingshuk Ghosh, Elisha Haas, Rohit Pappu, and Tobin Sosnick for helpful discussions during Protein Folding Consortium workshops sponsored by the National Science Foundation (NSF), and Eitan Lerner for comments on an earlier version of this article. J.S. gratefully acknowledges support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 21674055) and the Open Research Fund of State Key Laboratory of Polymer Physics and Chemistry, Changchun Institute of Applied Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant No. 201613). G.-N.G. was supported by an Ontario Graduate Scholarship. Support for this work was also provided by Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery grant No. RGPIN 342295-12 to C.C.G., Canadian Institutes of Health Research Operating grant No. MOP-84281 to H.S.C., and generous allotments of computational resources from SciNet of Compute/Calcul Canada.

Editor: Rohit Pappu.

Footnotes

Four figures are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(17)30848-2.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Haran G. How, when and why proteins collapse: the relation to folding. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2012;22:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuler B., Hofmann H. Single-molecule spectroscopy of protein folding dynamics--expanding scope and timescales. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2013;23:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gelman H., Gruebele M. Fast protein folding kinetics. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2014;47:95–142. doi: 10.1017/S003358351400002X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juette M.F., Terry D.S., Blanchard S.C. The bright future of single-molecule fluorescence imaging. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2014;20:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elbaum-Garfinkle S., Cobb G., Rhoades E. Tau mutants bind tubulin heterodimers with enhanced affinity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:6311–6316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315983111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banerjee P.R., Deniz A.A. Shedding light on protein folding landscapes by single-molecule fluorescence. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:1172–1188. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60311c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.König I., Zarrine-Afsar A., Schuler B. Single-molecule spectroscopy of protein conformational dynamics in live eukaryotic cells. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:773–779. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melo A.M., Coraor J., Rhoades E. A functional role for intrinsic disorder in the tau-tubulin complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:14336–14341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1610137113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schuler B., Soranno A., Nettels D. Single-molecule FRET spectroscopy and the polymer physics of unfolded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2016;45:207–231. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-062215-010915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uversky V.N., Oldfield C.J., Dunker A.K. Intrinsically disordered proteins in human diseases: introducing the D2 concept. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2008;37:215–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tompa P. Intrinsically disordered proteins: a 10-year recap. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2012;37:509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forman-Kay J.D., Mittag T. From sequence and forces to structure, function, and evolution of intrinsically disordered proteins. Structure. 2013;21:1492–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Z., Huang Y. Advantages of proteins being disordered. Protein Sci. 2014;23:539–550. doi: 10.1002/pro.2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen T., Song J., Chan H.S. Theoretical perspectives on nonnative interactions and intrinsic disorder in protein folding and binding. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2015;30:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Das R.K., Ruff K.M., Pappu R.V. Relating sequence encoded information to form and function of intrinsically disordered proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2015;32:102–112. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sherman E., Haran G. Coil-globule transition in the denatured state of a small protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:11539–11543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601395103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merchant K.A., Best R.B., Eaton W.A. Characterizing the unfolded states of proteins using single-molecule FRET spectroscopy and molecular simulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:1528–1533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607097104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazouchi A., Zhang Z., Gradinaru C.C. Conformations of a metastable SH3 domain characterized by smFRET and an excluded-volume polymer model. Biophys. J. 2016;110:1510–1522. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Müller-Späth S., Soranno A., Schuler B. From the cover: charge interactions can dominate the dimensions of intrinsically disordered proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:14609–14614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001743107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu B., Chia D., Gradinaru C.C. The effect of intrachain electrostatic repulsion on conformational disorder and dynamics of the Sic1 protein. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2014;118:4088–4097. doi: 10.1021/jp500776v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song J., Gomes G.-N., Chan H.S. An adequate account of excluded volume is necessary to infer compactness and asphericity of disordered proteins by Förster resonance energy transfer. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015;119:15191–15202. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b09133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gomes G.-N., Gradinaru C.C. Insights into the conformations and dynamics of intrinsically disordered proteins using single-molecule fluorescence. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2017.06.008. S1570-9639(17)30129-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang F., Ying L., Fersht A.R. Direct observation of barrier-limited folding of BBL by single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:16239–16244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909126106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu J., Campos L.A., Muñoz V. Exploring one-state downhill protein folding in single molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:179–184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111164109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan H.S., Zhang Z., Liu Z. Cooperativity, local-nonlocal coupling, and nonnative interactions: principles of protein folding from coarse-grained models. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2011;62:301–326. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-032210-103405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skinner J.J., Yu W., Sosnick T.R. Benchmarking all-atom simulations using hydrogen exchange. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:15975–15980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404213111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li M., Liu Z. Dimensions, energetics, and denaturant effects of the protein unstructured state. Protein Sci. 2016;25:734–747. doi: 10.1002/pro.2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung H.S., Eaton W.A. Single-molecule fluorescence probes dynamics of barrier crossing. Nature. 2013;502:685–688. doi: 10.1038/nature12649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Z., Chan H.S. Transition paths, diffusive processes, and preequilibria of protein folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:20919–20924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209891109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borg M., Mittag T., Chan H.S. Polyelectrostatic interactions of disordered ligands suggest a physical basis for ultrasensitivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:9650–9655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702580104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mittag T., Marsh J., Forman-Kay J.D. Structure/function implications in a dynamic complex of the intrinsically disordered Sic1 with the Cdc4 subunit of an SCF ubiquitin ligase. Structure. 2010;18:494–506. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fuxreiter M., Tompa P. Fuzzy complexes: a more stochastic view of protein function. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012;725:1–14. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0659-4_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Csizmok V., Orlicky S., Forman-Kay J.D. An allosteric conduit facilitates dynamic multisite substrate recognition by the SCF(Cdc4) ubiquitin ligase. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:13943. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chong P.A., Forman-Kay J.D. Liquid-liquid phase separation in cellular signaling systems. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2016;41:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Srivastava D., Muthukumar M. Sequence dependence of conformations of polyampholytes. Macromolecules. 1996;29:2324–2326. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Das R.K., Pappu R.V. Conformations of intrinsically disordered proteins are influenced by linear sequence distributions of oppositely charged residues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:13392–13397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304749110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sawle L., Ghosh K. A theoretical method to compute sequence dependent configurational properties in charged polymers and proteins. J. Chem. Phys. 2015;143:085101. doi: 10.1063/1.4929391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin Y.-H., Forman-Kay J.D., Chan H.S. Sequence-specific polyampholyte phase separation in membraneless organelles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016;117:178101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.178101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin Y.-H., Chan H.S. Phase separation and single-chain compactness of charged disordered proteins are strongly correlated. Biophys. J. 2017;112:2043–2046. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ziv G., Haran G. Protein folding, protein collapse, and Tanford’s transfer model: lessons from single-molecule FRET. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:2942–2947. doi: 10.1021/ja808305u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hofmann H., Nettels D., Schuler B. Single-molecule spectroscopy of the unexpected collapse of an unfolded protein at low pH. J. Chem. Phys. 2013;139:121930. doi: 10.1063/1.4820490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Möglich A., Joder K., Kiefhaber T. End-to-end distance distributions and intrachain diffusion constants in unfolded polypeptide chains indicate intramolecular hydrogen bond formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:12394–12399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604748103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoo T.Y., Meisburger S.P., Plaxco K. Small-angle x-ray scattering and single-molecule FRET spectroscopy produce highly divergent views of the low-denaturant unfolded state. J. Mol. Biol. 2012;418:226–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watkins H.M., Simon A.J., Plaxco K.W. Random coil negative control reproduces the discrepancy between scattering and FRET measurements of denatured protein dimensions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:6631–6636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418673112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holehouse A.S., Perana I., Pappu R.V. Simulations and experiments provide a convergent view of protein unfolded states under folding conditions. Biophys. J. 2017;112:315a. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Plaxco K.W., Millett I.S., Baker D. Chain collapse can occur concomitantly with the rate-limiting step in protein folding. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1999;6:554–556. doi: 10.1038/9329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jacob J., Krantz B., Sosnick T.R. Early collapse is not an obligate step in protein folding. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;338:369–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O’Brien E.P., Morrison G., Thirumalai D. How accurate are polymer models in the analysis of Förster resonance energy transfer experiments on proteins? J. Chem. Phys. 2009;130:124903. doi: 10.1063/1.3082151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kellner R., Hofmann H., Schuler B. Single-molecule spectroscopy reveals chaperone-mediated expansion of substrate protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:13355–13360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407086111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maity H., Reddy G. Folding of Protein L with implications for collapse in the denatured state ensemble. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:2609–2616. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b11300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li M., Sun T., Liu Z. Dimension conversion and scaling of disordered protein chains. Mol. Biosyst. 2016;12:2932–2940. doi: 10.1039/c6mb00415f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zheng W., Borgia A., Best R.B. Probing the action of chemical denaturant on an intrinsically disordered protein by simulation and experiment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:11702–11713. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b05443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Borgia A., Zheng W., Schuler B. Consistent view of polypeptide chain expansion in chemical denaturants from multiple experimental methods. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:11714–11726. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b05917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haas E., Katchalski-Katzir E., Steinberg I.Z. Brownian motion of the ends of oligopeptide chains in solution as estimated by energy transfer between the chain ends. Biopolymers. 1978;17:11–31. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jacob M.H., Dsouza R.N., Nau W.M. Diffusion-enhanced Förster resonance energy transfer and the effects of external quenchers and the donor quantum yield. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2013;117:185–198. doi: 10.1021/jp310381f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Toptygin D., Chin A.F., Hilser V.J. Effect of diffusion on resonance energy transfer rate distributions: implications for distance measurements. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015;119:12603–12622. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b06567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Piana S., Klepeis J.L., Shaw D.E. Assessing the accuracy of physical models used in protein-folding simulations: quantitative evidence from long molecular dynamics simulations. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2014;24:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen T., Chan H.S. Effects of desolvation barriers and sidechains on local-nonlocal coupling and chevron behaviors in coarse-grained models of protein folding. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014;16:6460–6479. doi: 10.1039/c3cp54866j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rauscher S., Gapsys V., Grubmüller H. Structural ensembles of intrinsically disordered proteins depend strongly on force field: a comparison to experiment. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:5513–5524. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang J., Rauscher S., MacKerell A.D., Jr. CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:71–73. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Best R.B. Computational and theoretical advances in studies of intrinsically disordered proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2017;42:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Levine Z.A., Shea J.-E. Simulations of disordered proteins and systems with conformational heterogeneity. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2017;43:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tavakoli, M., J. N. Taylor, …, S. Pressé. 2016. Single molecule data analysis: an introduction. arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.00403.

- 64.Levitt M. A simplified representation of protein conformations for rapid simulation of protein folding. J. Mol. Biol. 1976;104:59–107. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Metropolis N., Rosenbluth A.W., Teller E. Equation of state calculation by fast computing machines. J. Chem. Phys. 1953;21:1087–1092. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Song J., Ng S.C., Chan H.S. Polycation-π interactions are a driving force for molecular recognition by an intrinsically disordered oncoprotein family. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013;9:e1003239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Verdier P.H., Stockmayer W.H. Monte Carlo calculations on dynamics of polymers in dilute solution. J. Chem. Phys. 1962;36:227–235. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lal M. Monte Carlo computer simulation of chain molecules. I. Mol. Phys. 1969;17:57–64. [Google Scholar]

- 69.McCarney E.R., Werner J.H., Plaxco K.W. Site-specific dimensions across a highly denatured protein; a single molecule study. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;352:672–682. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kikhney A.G., Svergun D.I. A practical guide to small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) of flexible and intrinsically disordered proteins. FEBS Lett. 2015;589(19 Pt A):2570–2577. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kohn J.E., Millett I.S., Plaxco K.W. Random-coil behavior and the dimensions of chemically unfolded proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:12491–12496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403643101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Inman H.F., Bradley E.L., Jr. The overlapping coefficient as a measure of agreement between probability distributions and point estimation of the overlap of two normal densities. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods. 1989;18:3851–3874. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hu J., Chen T., Zhang Z. A critical comparison of coarse-grained structure-based approaches and atomic models of protein folding. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017;19:13629–13639. doi: 10.1039/c7cp01532a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Borgia A., Wensley B.G., Schuler B. Localizing internal friction along the reaction coordinate of protein folding by combining ensemble and single-molecule fluorescence spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:1195. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Choy W.-Y., Forman-Kay J.D. Calculation of ensembles of structures representing the unfolded state of an SH3 domain. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;308:1011–1032. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marsh J.A., Forman-Kay J.D. Ensemble modeling of protein disordered states: experimental restraint contributions and validation. Proteins. 2012;80:556–572. doi: 10.1002/prot.23220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Antonov L.D., Olsson S., Hamelryck T. Bayesian inference of protein ensembles from SAXS data. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016;18:5832–5838. doi: 10.1039/c5cp04886a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wallin S., Chan H.S. A critical assessment of the topomer search model of protein folding using a continuum explicit-chain model with extensive conformational sampling. Protein Sci. 2005;14:1643–1660. doi: 10.1110/ps.041317705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Baldwin R.L. The nature of protein folding pathways: the classical versus the new view. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;5:103–109. doi: 10.1007/BF00208801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shortle D., Ackerman M.S. Persistence of native-like topology in a denatured protein in 8 M urea. Science. 2001;293:487–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1060438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Meng W., Lyle N., Pappu R.V. Experiments and simulations show how long-range contacts can form in expanded unfolded proteins with negligible secondary structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:2123–2128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216979110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sadqi M., Fushman D., Muñoz V. Atom-by-atom analysis of global downhill protein folding. Nature. 2006;442:317–321. doi: 10.1038/nature04859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chan H.S., Shimizu S., Kaya H. Cooperativity principles in protein folding. Methods Enzymol. 2004;380:350–379. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)80016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bai Y., Sosnick T.R., Englander S.W. Protein folding intermediates: native-state hydrogen exchange. Science. 1995;269:192–197. doi: 10.1126/science.7618079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shimizu S., Chan H.S. Origins of protein denatured state compactness and hydrophobic clustering in aqueous urea: inferences from nonpolar potentials of mean force. Proteins. 2002;49:560–566. doi: 10.1002/prot.10263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kaya H., Chan H.S. Explicit-chain model of native-state hydrogen exchange: implications for event ordering and cooperativity in protein folding. Proteins. 2005;58:31–44. doi: 10.1002/prot.20286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Knott M., Chan H.S. Criteria for downhill protein folding: calorimetry, chevron plot, kinetic relaxation, and single-molecule radius of gyration in chain models with subdued degrees of cooperativity. Proteins. 2006;65:373–391. doi: 10.1002/prot.21066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Martin E.W., Holehouse A.S., Mittag T. Sequence determinants of the conformational properties of an intrinsically disordered protein prior to and upon multisite phosphorylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:15323–15335. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b10272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pappu R.V., Srinivasan R., Rose G.D. The Flory isolated-pair hypothesis is not valid for polypeptide chains: implications for protein folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:12565–12570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.23.12565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fitzkee N.C., Rose G.D. Reassessing random-coil statistics in unfolded proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:12497–12502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404236101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Orevi T., Ben Ishay E., Haas E. Early closure of a long loop in the refolding of adenylate kinase: a possible key role of non-local interactions in the initial folding steps. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;385:1230–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lerner E., Orevi T., Haas E. Kinetics of fast changing intramolecular distance distributions obtained by combined analysis of FRET efficiency kinetics and time-resolved FRET equilibrium measurements. Biophys. J. 2014;106:667–676. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.11.4500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Orevi T., Rahamim G., Haas E. Sequential closure of loop structures forms the folding nucleus during the refolding transition of the Escherichia coli adenylate kinase molecule. Biochemistry. 2016;55:79–91. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fuertes G., Banterle N., Lemke E.A. Decoupling of size and shape fluctuations in heteropolymeric sequences reconciles discrepancies in SAXS vs. FRET measurements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E6342–E6351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704692114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.