Abstract

Background

There is limited information to support definitive recommendations concerning the role of diet in the development of type II Diabetes mellitus (T2DM). The results of the latest meta-analyses suggest that an increased consumption of green leafy vegetables may reduce the incidence of diabetes, with either no association or weak associations demonstrated for total fruit and vegetable intake. Few studies have, however, focused on older subjects.

Methods

The relationship between T2DM and fruit and vegetable intake was investigated using data from the NIH-AARP study and the EPIC elderly study. All participants below the age of 50 and/or with a history of cancer, diabetes or coronary heart disease were excluded from the analysis. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to calculate the odds ratio of T2DM comparing the highest with the lowest estimated portions of fruit, vegetable, green leafy vegetables and cabbage intake.

Results

Comparing people with the highest and the lowest estimated portions of fruit, vegetable or green leafy vegetable intake indicated no association with the risk of T2DM. However, although the pooled OR across all studies showed no effect overall, there was significant heterogeneity across cohorts and independent results from the NIH-AARP study showed that fruit and green leafy vegetable intake was associated with a reduced risk of T2DM OR 0.95 (95% CI 0.91,0.99) and OR 0.87 (95% CI 0.87,0.90) respectively.

Conclusion

Fruit and vegetable intake was not shown to be related to incident T2DM in older subjects. Summary analysis also found no associations between green leafy vegetable and cabbage intake and the onset of T2DM. Future dietary pattern studies may shed light on the origin of the heterogeneity across populations.

Keywords: fruit, vegetable, green leafy vegetable, diabetes, elderly, CHANCES

Introduction

The chronic hyperglycaemia that characterizes Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is caused by impaired insulin secretion or action and results from the interaction between a genetic predisposition and environmental risk factors [1]. In 2004, an estimated 3.4 million people died from the consequences of diabetes or pre-diabetes. According to the WHO, this number is rising and will lead to diabetes being the 7th leading cause of death by 2030 [2]. Although the genetic basis of T2DM has yet to be identified, there is strong evidence that modifiable risk factors such as obesity and a sedentary lifestyle are among the non-genetic determinants of the disease [3–6]. However, other than avoidance of obesity, there is limited information for definitive recommendations regarding the role of diet in the development of T2DM [7–9]. The role of fruit and vegetable intake and risk of T2DM is even less recognized, especially with regards to green leafy vegetables, a rich source of polyphenols which are thought to be associated with increased insulin sensitivity [10].

The results of a recent meta-analysis suggests that an increased consumption of fruit and green leafy vegetables may be associated with a significantly reduced risk of T2DM, with no association or weak associations demonstrated for total vegetable intake. However, the former observation regarding green leafy vegetables is based on a limited number of studies [11]. Conversely, another more up-to-date meta-analysis reported a dose dependent association between fruit and vegetable intakes separately and a reduced risk of T2DM [12]. An earlier a meta-analysis carried out in 2010 [10] included a sub-analysis using studies with information on green leafy vegetable consumption. The summary estimates showed that greater intake of green leafy vegetables was associated with a 14% reduction in risk of T2DM. Similarly a meta-analysis by Cooper et al [13] also included a sub-analysis of green leafy vegetable intake showing an inverse association with T2DM. Neither study, however, was specifically focussed on older subjects. Therefore, the present study was undertaken to examine the association between T2DM and fruit and vegetables intake, including green leafy vegetables.

Methods

Study population

The aim of the Consortium on Health and Ageing Network of Cohorts in Europe and the United States (CHANCES) was to combine and integrate prospective cohort studies to produce, improve and clarify the evidence on ageing-related health characteristics and risk factors for chronic diseases in the elderly, and their socio-economic implications (www.chancesfp7.eu). Detailed characteristics of the cohorts have previously been described [14]. All variables used in the analyses from different cohorts were harmonised according to pre-agreed CHANCES data harmonisation rules. All of the cohorts obtained ethical approval and written informed consent from all participants.

Participants, aged 50 years and above, were included from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition elderly study (EPIC Elderly) [15] including Spain, Greece, The Netherlands, and Sweden (EPIC was treated as 4 different cohorts in the analysis); and the National Institutes of Health (NIH)-AARP Diet and Health Study United States [16].

Exclusions

Prior to the analysis, participants at baseline with missing information on chronic diseases (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer), below 50 years of age, missing or unrealistic information on body mass index (BMI) [if BMI >60 kg/m2 or <10 kg/m2] and with extreme energy intake were excluded (applying the cohort specific definitions).

Exposure

Habitual dietary intakes were assessed through compatible methods including food frequency questionnaires (FFQ) and, in some centers within the EPIC elderly study, records of intake over seven or 14 days that had been developed and validated within each center. In addition, a computerized instrument for recall of dietary intake over 24 hours was developed to collect information from a stratified random sample of the aggregate cohort. The aim was to calibrate the measurements across countries [17]. The number of FFQ items differed across cohorts. The number of FFQ items used in EPIC elderly was 200 compared to 124 items used in (NIH)-AARP and were both self-reported. (NIH)-AARP Data were thus harmonized across cohorts regarding definitions of food groups and nutrient units [18]. Fruit and vegetable intakes were calculated in terms of portions per day (1 portion = 80g). Green leafy vegetable and cabbage, which were less frequently consumed, were calculated in portions per week (1 portion = 80g).

Outcome

Information on Incident T2DM was collected through self-administered questionnaires or in interviews. The diagnosis of diabetes after the age of 50 was anticipated to be T2DM, as type 1 diabetes usually develops before the age of 40 [19]. All cohorts included in this analysis did not distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes, except for EPIC Elderly Greece.

Covariates

Model A of the analysis was adjusted for age and sex. Model B was adjusted for age, sex, BMI kg/m2; underweight (<18.5), normal (≥18.5–<25), overweight (≥25–<30), moderately obese (≥30–<35) and severely obese (≥35); habitual vigorous physical activity (yes/no) (defined as vigorous exercise at least once per week); energy intake (Kcal); alcohol consumption [Light = men (>0g & <40g daily), women (>0g & <20g daily); moderate = men (≥40g & <60g daily), women (≥20g & <40g daily); and heavy = men (≥60g daily), women (≥40g daily)]; education (primary or less, more than primary, college or university); and smoking (never, former, current) in all cohorts.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were carried out using STATA IC V.11.2 (Stata- Corp, Texas, USA) code available upon request. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to calculate the odds ratio (OR) of T2DM and 95 % confidence intervals (CI) comparing the highest with the lowest estimated intakes of fruit, vegetable, green leafy vegetables and cabbage. This type of analysis was used as the majority of the cohorts had no precise date of diagnosis during follow-up; hence cox modelling/time to event was not ideal. This analysis was conducted in two stages: deriving first the study-specific estimates and then a combined overall estimate; thereafter it was also stratified by categories of intake per day and by total intake of each of fruit, vegetable, green leafy vegetable and cabbage. Categories were developed to maintain consistency across cohorts and so that comparisons could be easily made. Categories for fruit and vegetables were <1.5, 1.5–2.4, 2.5–3.9 and ≥4 portions per day. For green leafy vegetables and cabbage, the categories were <1.5, 1.5–2.4, 2.5–3.9 and ≥4 portions per week.

We computed both fixed effects models, and random effects models using the DerSimonian-Laird method [20]. Due to substantial heterogeneity across cohort results as assessed with I2- and Q-statistics, random effects estimates are reported as the main results, since random effects models allow for variability of effects across individual studies.

Results

The number of diabetes cases at follow up across the cohorts was as follows (data not shown): NIH-AARP: 22,782; EPIC Elderly All: 1567; EPIC Elderly Spain: 138; EPIC Elderly Greece: 1077; EPIC Elderly Netherlands: 234; and EPIC Elderly Sweden: 118. The characteristics of subjects in each of the cohorts at baseline are presented in Table 1. EPIC Elderly Spain had a higher proportion of individuals in the overweight BMI category, as well as in the moderately obese category. EPIC Elderly Greece, however, had the highest proportion of individuals in the severely obese category. Although the energy intakes (Kcal) were similar across the cohorts, EPIC Elderly Sweden had the lowest intakes. EPIC Elderly Spain had the lowest number of individuals who engaged in vigorous physical activity, while EPIC Elderly Netherlands had the highest proportion of individuals who said they did vigorous activity.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of CHANCES participants

| Baseline variables | CHANCES cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| NIH-AARP | EPIC Elderly All |

EPIC Elderly Spain |

EPIC Elderly Greece |

EPIC Elderly The Netherlands |

EPIC Elderly Sweden |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total N | 401909 | 20629 | 4309 | 7567 | 5786 | 2967 |

|

| ||||||

| Mean follow up time of study (years) | 10.6 | 11.8 | 13.1 | 10.0 | 12.6 | 13.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Age at baseline1 | 62 ± 5 | 64 ± 4 | 63 ± 2 | 67 ± 5 | 64 ± 3 | 60 ± 1 |

|

| ||||||

| BMI (Kg/m2)2 | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Underweight | 4,343 (1) | 134 (0.65) | 4 (0.09) | 29 90.380 | 69 (1) | 32 (1) |

| Normal | 145,197 (37) | 5,650 (27) | 496(12) | 1,292 (170 | 2,518 (44) | 1,344 (45) |

| Overweight | 166,893 (43) | ,850 (43) | 2,041 (47) | 3,184 (42) | 2,412 (42) | 1,213 (41) |

| Modestly obese | 56,134 (14) | 4,531 (22) | 1,367 (32) | 2,257 (30) | 639 (11) | 268 (9) |

| Severely obese | 20,096 (5) | 1,464 (7) | 401 (9) | 805 (11) | 148 (3) | 110 (4) |

|

| ||||||

| Vigorous Physical activity2 | 186,334 (46) | 5,080 (29) | 222 (5) | 1,603 (22) | 3,255 (58) | na |

|

| ||||||

| Energy intake in Kcal1 | 1,822 ± 651 | 1,835 ± 583 | 2,036 ± 674 | 1,842 ± 586 | 1,772 ± 429 | 1,647 ± 600 |

|

| ||||||

| Alcohol consumption/day2 | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 0 | 88,022 (22) | 5,771 (28) | 1,722 (40) | 2,479 (33) | 1,197 (21) | 373 (13) |

| 1 | 274,779 (68) | 13,031 (63) | 1,987 (46) | 4,690 (62) | 3,701 (65) | 2,593 (87) |

| 2 | 19,638 (5) | 1,257 (6) | 344 (8) | 243 (3) | 669 (12) | 1 (0.03) |

| 3 | 19,470 (5) | 570 (3) | 256 (6) | 155 (2) | 159 (30) | - |

|

| ||||||

| Sex 2 | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Male | 231,259 (58) | 6,394 (31) | 1,858 (43) | 2,873 (38) | 263 (5) | 1,400 (47) |

|

| ||||||

| Education2 | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Primary or less | 2,592 (0.6) | 14,071 (68) | 3,674 (85) | 6,883 (91) | 1,896 (33) | 1,618 (55) |

| More than primary | 95,522 (24) | 4,927 (24) | 308 (7) | 417 (6) | 3,228 (56) | 974 (33) |

| College or University | 293,119 (73) | 1,523 (7) | 277 (6) | 238 (3) | 655 (11) | 353 (12) |

|

| ||||||

| Smoking status2 | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Never | 147,429 (37) | 12,745 (62) | 2,896 (67) | 5,269 (70) | 2,778 (48) | 1,802 (61) |

| Former | 190,969 (48) | 4,475 (22) | 676 (16) | 1,230 (16) | 1,960 (34) | 609 (21) |

| Current | 48,597 (12) | 3,126 (15) | 734 (17) | 857 (11) | 1,047 (18) | 488 (16) |

|

| ||||||

| Fruits and Vegetables 3 | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Fruits p/day | 3.7 (2.1–5.9) | 3.2 (1.9–4.7) | 3.6 (2.3–5.7) | 4.0 (2.9–5.3) | 2.9 (1.6–3.9) | 1.7 (0.9–2.9) |

| Vegetables p/day | 3.2 (2.1–4.6) | 2.4 (1.4–4.5) | 2.5 (1.6–3.8) | 4.8 (3.7–6.2) | 1.6 (1.2–2.0) | 0.7 (0.4–1.4) |

| Green leafy vegetables p/w | 2.3 (0.9–4.8) | 2.7 (1.2–5.0) | 3.9 (1.7–7.7) | 4.1 (2.5–6.2) | 2.4 (1.4–3.5) | 0.03 (0.01–0.3) |

| Cabbage p/w | 0.3 (0.08–0.6) | 1.2 (0.3–2.4) | 0.1 (0.0–0.8) | 1.9 (0.9–2.8) | 1.7 (1.0–2.7) | 0.2 (0.02–0.37) |

Abbreviations: N: number, BMI: body mass index, kcal: kilocalorie, na: not available, p: portion, w: week. Exclusions: Age<50, History of Coronary Heart Disease, Cancer and Diabetes. Alcohol consumption/day= 0:non-drinker, 1: Light = men (>0g & <40g daily), women (>0g & <20g daily); 2: Moderate = men (≥40g & <60g daily), women (≥20g & <40g daily); 3: Heavy = men (≥60g daily), women (≥40g daily).

Mean and standard deviation

Number and percentage

Median and Interquartile range

The highest proportion of individuals who drank heavily were those of the EPIC Elderly Netherlands cohort. They were also mostly women, with men only making up 5% of the cohort participants. The NIH-AARP study had more highly educated subjects, and the highest number of former smokers. EPIC Elderly Greece had the highest proportion of current smokers.

Intakes of fruit and vegetables, which were calculated in portions per day (for fruit and vegetable) or per week (green leafy vegetables and cabbage) are also shown in Table 1. Intakes varied between cohorts especially between subgroups of vegetables. For example, intakes of cabbage were lowest in the EPIC Elderly Sweden and Spain cohorts. EPIC Elderly Greece had the highest intakes across all four categories, across all cohorts, whereas EPIC Elderly Sweden had lowest number of individuals in all four categories.

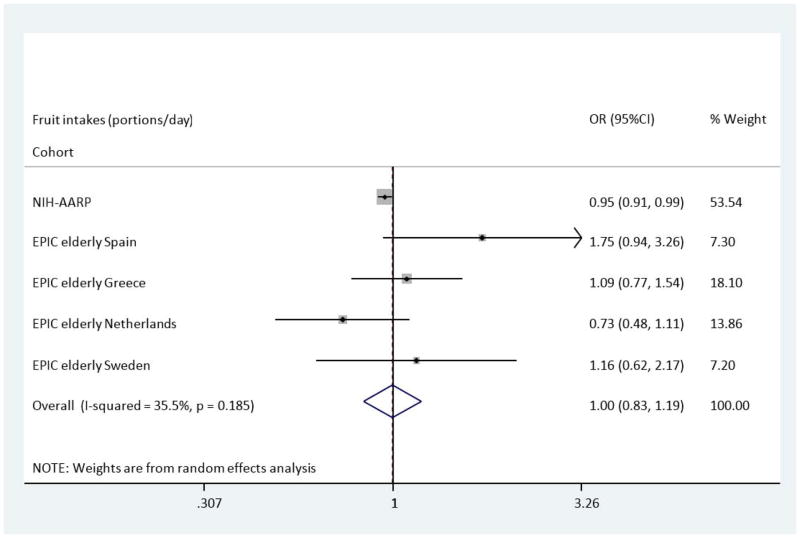

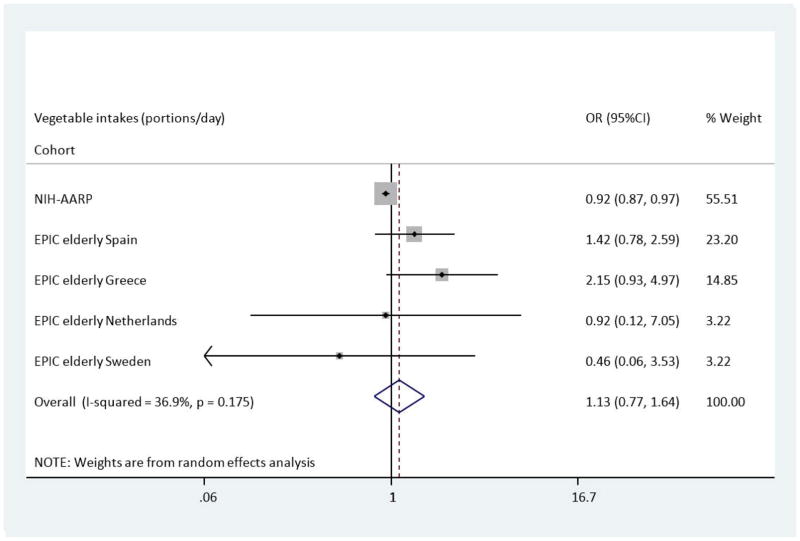

Median intakes and ORs (95% CI) for T2DM are presented in (Table 2) and (Table 3) for categories as well as total intake per day (1 portion = 80g). Compared with the lowest category of intake, the multivariate adjusted OR (Model B) of T2DM across categories of fruit showed a slightly reduced risk of T2DM in the NIH-AARP study; OR: 0.95 (95%CI 0.91–0.99). This, however, was not the case in the EPIC Elderly cohorts where no significant associations were found; for example, EPIC Elderly (all), OR: 1.01 (95%CI 0.80–1.28). Figure 1 shows the overall pooled multivariate odds ratio for T2DM comparing the highest with the lowest fruit intakes across the NIH-AARP & EPIC Elderly cohorts. The results show no overall association with the risk of T2DM, OR: 1.00 (95%CI 0.83–1.19). Across categories of vegetable intake, there was no association with risk of T2DM across EPIC Elderly (all and separately) after adjustments were made in Model B. A reduced risk of T2DM, comparing the highest to the lowest category of vegetable intake, was apparent in NIH-AARP, OR: 0.92 (95%CI 0.87–0.97). In the Spanish and Greek EPIC Elderly cohorts there were non-significant increases in risk of T2DM, OR: 1.42 (95%CI 0.78–2.58) and OR: 2.15 (95%CI 0.93–5.03), respectively. Figure 2 shows the pooled analysis for vegetable intake and T2DM risk. The pooled OR in Model B was 1.13 (95%CI 0.77–1.64) indicating no overall association between vegetable intake and incident T2DM.

Table 2.

Association between Diabetes, fruits and vegetables in CHANCES participants

| Portions/day of fruit intake | P | Total intake 1 portion/day | Portions/day of vegetable intake | P | Total intake | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| <1.5 | 1.5–2.4 | 2.5–3.9 | ≥4 | <1.5 | 1.5–2.4 | 2.5–3.9 | ≥4 | |||||

| NIH-AARP | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Median | 0.82 | 1.99 | 3.24 | 7.73 | 1.04 | 2.02 | 3.20 | 6.41 | ||||

| Model Aa: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.93(0.88–0.97) | 0.86(0.82–0.89) | 0.86(0.83–0.89) | <0.01 | 1.00(1.00–1.00) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.91(0.87–0.95) | 0.89(0.85–0.93) | 0.98(0.93–1.02) | 0.03 | 1.02(1.01–1.02) |

| Model Bb: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.96(0.91–1.02) | 0.95(0.91–0.99) | 0.95(0.91–0.99) | 0.04 | 1.00(0.99–1.01) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.92(0.87–0.97) | 0.88(0.84–0.94) | 0.92(0.87–0.97) | 0.14 | 1.00(0.99–1.01) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| EPIC Elderly (All) | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Median | 0.87 | 1.89 | 3.18 | 5.3 | 0.97 | 1.9 | 3.18 | 5.5 | ||||

| Model Aa: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.86(0.69–1.07) | 0.96(0.79–1.16) | 1.01(0.83–1.22) | 0.24 | 1.01(0.98–1.04) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.98(0.79–1.21) | 1.19(0.95–1.51) | 1.23(0.97–1.56) | 0.05 | 1.03(0.99–1.06) |

| Model Bb: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.95(0.73–1.23) | 1.01(0.80–1.28) | 1.01(0.80–1.28) | 0.88 | 1.00(0.97–1.03) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.99(0.79–1.26) | 1.11(0.86–1.45) | 1.05(0.79–1.37) | 0.72 | 0.99(0.96–1.03) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| EPIC Elderly Spain | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Median | 0.57 | 1.94 | 3.21 | 5.98 | 1.05 | 1.98 | 3.11 | 5.03 | ||||

| Model Aa: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.59(0.82–3.13) | 1.15(0.61–2.18) | 1.47(0.82–2.63) | 0.36 | 1.02(0.96–1.08) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.76(1.04–2.96) | 1.52(0.90–2.56) | 1.35(0.76–2.37) | 0.76 | 0.99(0.91–1.99) |

| Model Bb: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.83(0.91–3.67) | 1.28(0.66–2.54) | 1.75(0.94–3.26) | 0.17 | 1.04(0.98–1.0) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.89(1.10–3.26) | 1.66(0.96–2.87) | 1.42(0.78–2.58) | 0.72 | 0.99(0.90–1.00) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| EPIC Elderly Greece | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Median | 1.06 | 2.08 | 3.28 | 5.29 | 1.15 | 2.12 | 3.39 | 5.61 | ||||

| Model Aa: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.04(0.72–1.49) | 1.08(0.78–1.49) | 1.13(0.83–1.56) | 0.24 | 1.01(0.98–1.04) | 1.00 (Ref) | 2.14(0.88–5.16) | 2.62(1.14–6.07) | 2.73(1.19–6.27) | 0.05 | 1.03(0.99–1.07) |

| Model Bb: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.12(0.77–1.64) | 1.09(0.77–1.54) | 1.09(0.77–1.55) | 0.88 | 1.00(0.96–1.04) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.96(0.81–4.77) | 2.29(0.99–5.36) | 2.15(0.93–5.03) | 0.72 | 0.99(0.95–1.04) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| EPIC Elderly Netherlands | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Median | 0.96 | 1.73 | 3.14 | 4.80 | 1.17 | 1.86 | 2.81 | 4.33 | ||||

| Model Aa: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.59(0.39–0.88) | 0.84(0.58–1.21) | 0.73(0.49–1.09) | 0.63 | 0.96(0.89–1.04) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.80(0.6–1.06) | 0.87(0.56–1.37) | 0.71(0.09–5.33) | 0.29 | 0.97(0.79–1.19) |

| Model Bb: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.57(0.37–0.88) | 0.89(0.61–1.32) | 0.73(0.48–1.12) | 0.74 | 0.96(0.88–1.04) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.72(0.54–0.98) | 0.73(0.46–1.17) | 0.92(0.12–7.12) | 0.09 | 0.90(0.73–1.12) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| EPIC Elderly Sweden | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Median | 0.81 | 1.89 | 3.08 | 4.50 | 0.58 | 1.89 | 2.96 | 4.67 | ||||

| Model Aa: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.78(0.49–1.27) | 0.88(0.52–1.49) | 1.21(0.68–2.16) | 0.59 | 1.07(0.96–1.19) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.75(0.41–1.39) | 2.17(1.17–4.00) | 0.53(0.07–3.92) | 0.42 | 1.11(0.93–1.32) |

| Model Bb: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.72(0.43–1.19) | 0.87(0.50–1.52) | 1.16(0.62–2.15) | 0.67 | 1.07(0.95–1.20) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.68(0.35–1.29) | 2.17(1.14–4.13) | 0.46(0.06–3.46) | 0.59 | 1.09(0.91–1.31) |

Abbreviations: g: grams; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence Intervals.

Model A: adjusted for sex and age.

Model B: adjusted for age, sex, BMI, physical activity, energy intake, alcohol consumption, education and smoking. P is for trend across categories.

Table 3.

Association between Diabetes, green leafy vegetables and cabbage in CHANCES participants

| Portions/week of leafy green vegetables intake | P | Total intake 1 portion/day | Portions/week of cabbage intake | P | Total intake | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| <1.5 | 1.5–2.4 | 2.5–3.9 | ≥4 | <1.5 | 1.5–2.4 | 2.5–3.9 | ≥4 | |||||

| NIH-AARP | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Median | 0.65 | 1.98 | 3.10 | 8.06 | 0.32 | 1.63 | 3.90 | 9.79 | ||||

| Model Aa: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.86(0.83–0.89) | 0.81(0.77–0.85) | 0.82(0.79–0.85) | <0.01 | 0.98(0.98–0.98) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.09(1.05–1.15) | 1.24(1.16–1.33) | 1.19(1.06–1.33) | <0.01 | 1.04(1.03–1.05) |

| Model Bb: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.90(0.86–0.94) | 0.89(0.85–0.94) | 0.87(0.84–0.90) | <0.01 | 0.98(0.98–0.99) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.06(1.01–1.12) | 1.09(1.00–1.18) | 1.07(0.94–1.21) | <0.01 | 1.02(1.01–1.03) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| EPIC Elderly (All) | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Median | 0.32 | 2.04 | 3.14 | 6.18 | 0.37 | 1.99 | 3.07 | 4.96 | ||||

| Model Aa: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.11(0.89–1.38) | 1.28(1.05–1.57) | 1.30(1.09–1.59) | <0.01 | 1.02(0.99–1.03) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.94(0.82–1.09) | 1.16(1.00–1.34) | 0.98(0.80–1.19) | 0.02 | 1.00(0.97–1.04) |

| Model Bb: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.09(0.87–1.37) | 1.25(1.01–1.53) | 1.23(1.01–1.50) | 0.02 | 1.00(0.99–1.02) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.89(0.76–1.04) | 1.09(0.94–1.27) | 0.96(0.77–1.19) | 0.15 | 0.99(0.94–1.03) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| EPIC Elderly Spain | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Median | 0.55 | 1.93 | 3.14 | 7.66 | 0 | 2.11 | 2.93 | 4.95 | ||||

| Model Aa: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.77(1.01–3.14) | 1.28(0.73–2.24) | 1.02(0.64–1.62) | 0.44 | 0.98(0.95–1.02) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.79(0.38–1.63) | 0.96(0.38–2.39) | 0.79(0.37–1.73) | 0.49 | 0.94(0.83–1.06) |

| Model Bb: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.74(0.97–3.11) | 1.39(0.79–2.47) | 1.04(0.64–1.68) | 0.52 | 0.98(0.95–1.01) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.86(0.41–1.78) | 0.96(0.38–2.40) | 0.80(0.37–1.75) | 0.54 | 0.95(0.84–1.07) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| EPIC Elderly Greece | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Median | 0.87 | 2.13 | 3.13 | 6.18 | 0.84 | 2.06 | 3.06 | 4.88 | ||||

| Model Aa: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.26(0.92–1.72) | 1.57(1.18–2.11) | 1.61(1.22–2.12) | <0.01 | 1.03(1.01–1.05) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.99(0.83–1.18) | 1.28(1.09–1.51) | 1.14(0.90–1.43) | 0.02 | 1.03(0.99–1.07) |

| Model Bb: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.23(0.89–1.71) | 1.55(1.14–2.11) | 1.52(1.13–2.04) | 0.02 | 1.02(0.99–1.04) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.93(0.77–1.11) | 1.21(1.07–1.44) | 1.09(0.85–1.41) | 0.15 | 1.02(0.98–1.07) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| EPIC Elderly Netherlands | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Median | 0.97 | 1.99 | 3.14 | 4.95 | 0.92 | 1.92 | 3.08 | 4.97 | ||||

| Model Aa: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.88(0.61–1.29) | 0.99(0.65–1.33) | 1.13(0.77–1.68) | 0.49 | 1.05(0.97–1.14) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.82(0.59–1.12) | 0.74(0.51–1.08) | 0.57(0.33–0.97) | 0.01 | 0.86(0.79–0.96) |

| Model Bb: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.89(0.61–1.31) | 0.87(0.60–1.26) | 1.03(0.69–1.54) | 0.86 | 1.02(0.94–1.10) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.81(0.58–1.11) | 0.79(0.54–1.16) | 0.61(0.35–1.05) | 0.04 | 0.87(0.78–0.97) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| EPIC Elderly Sweden | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Median | 0.03 | 1.77 | 3.52 | 7.04 | 0.17 | 1.88 | 3.75 | 5.25 | ||||

| Model Aa: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.88(0.12–6.56) | 2.86(0.52–9.60) | - | 0.60 | 1.12(0.89–1.42) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.85(0.27–2.75) | 1.50(0.68–3.31) | 0.67(0.09–4.90) | 0.73 | 1.07(0.92–1.23) |

| Model Bb: OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.76(0.09–5.86) | 2.98(0.85–10.4) | - | 0.67 | 1.12(0.87–1.43) | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.77(0.23–2.59) | 1.53(0.68–3.48) | 0.76(0.10–5.71) | 0.69 | 1.04(0.90–1.21) |

Abbreviations: g: grams; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence Intervals.

Model A: adjusted for sex and age.

Model B: adjusted for age, sex, BMI, physical activity, energy intake, alcohol consumption, education and smoking. P is for trend across categories.

Figure 1.

Odds Ratio of T2DM comparing the highest with lowest estimated portions of fruit intake across the NIH-AARP & EPIC elderly study-Meta-analysis Results

Figure 2.

Odds Ratio of T2DM comparing the highest with lowest estimated portions of vegetable intake across the NIH-AARP & EPIC elderly study-Meta-analysis Results

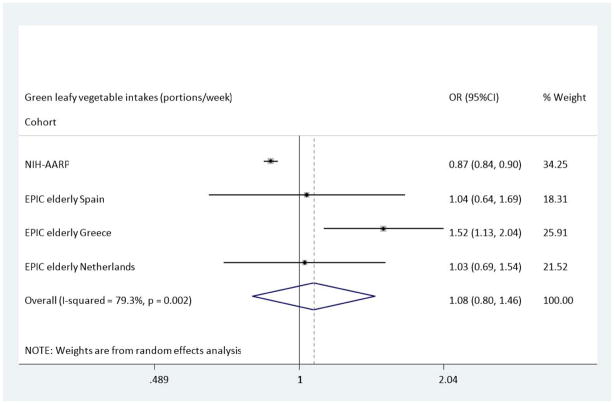

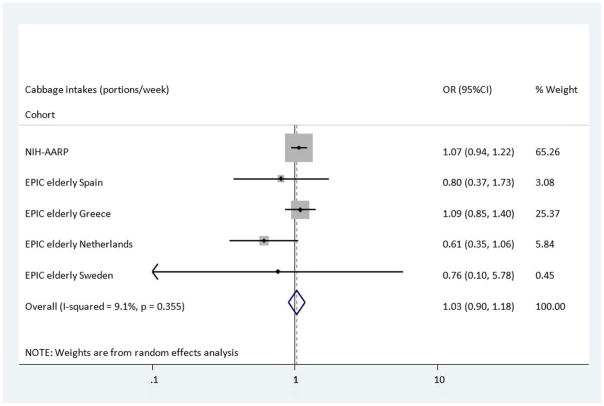

In the NIH-AARP cohort, green leafy vegetable intake was associated with a reduced risk of T2DM which retained its significance in Model B, OR: 0.87 (95%CI 0.84–0.90). However the trends in the EPIC Elderly cohorts were in the opposite direction, with an increase in the odds of developing T2DM in those with the highest intakes of green leafy vegetables; EPIC Elderly All, OR: 1.23(95%CI 1.01–1.50), and EPIC Elderly Greece, OR: 1.52 (1.13–2.04). Nevertheless, the pooled analysis, shown in Figure 3, indicated no overall association between intake of green leafy vegetables and T2DM, OR: 1.08 (0.80, 1.46). Finally, when compared to the lowest category of intake, those with highest cabbage intakes had a reduced risk of T2DM across the EPIC Elderly Netherlands cohort after adjustments were made in Model B, OR: 0.61(95%CI 0.35–1.05), though the Confidence Limits could not exclude the null value. In the analysis using the NIH-AARP study, there were also associations found between cabbage intakes and incident T2DM, however these indicated a small increased risk for T2DM, OR: 1.07(0.94–1.21). Thus overall, no association was found between cabbage intake and incident T2DM (Figure 4), OR: 1.03 (95%CI 0.90, 1.18).

Figure 3.

Odds Ratio of T2DM comparing the highest with lowest estimated portions of green leafy vegetable intake across the NIH-AARP & EPIC elderly study-Meta-analysis Results

Figure 4.

Odds Ratio of T2DM comparing the highest with lowest estimated portions of cabbage intake across the NIH-AARP & EPIC elderly study-Meta-analysis Results

Discussion

Associations found between intakes of fruits, vegetables, green leafy vegetables and cabbage and incident T2DM varied, as they showed both a reduced risk of T2DM as well as an increased risk across these CHANCES cohorts. Nevertheless, although there was heterogeneity between cohorts, the overall pooled results using multiple cohorts from different countries showed no association with risk of incident T2DM. Being so large, the NIH AARP study has a major impact on our pooled results so in a separate sensitivity analysis we pooled results for all EPIC Elderly cohorts excluding NIH-AARP, which offered the following results per portion: for fruits OR: 1.07 (95%CI 0.77,1.49); vegetables OR 1.49 (95%CI 0.94, 2.36); green leafy vegetables OR: 1.23 (95%CI 0.93, 1.62) and cabbage OR: 0.90 (95%CI 0.66, 1.23), re-affirming the null associations.

Similar results have been shown in two meta-analyses [10, 21]. The systematic review by Hamer & Chaida (2007) also included studies measuring antioxidant intake and incidence of T2DM in a separate meta-analysis. The relative risk of T2DM from consuming five or more servings of fruit and vegetables a day was 0.96 (95% CI, 0.79–1.17, P=0.96), and 1.01 (0.88–1.15, P=0.88) for three or more servings of fruit, and 0.97 (0.86–1.10, P=0.59) for three or more servings of vegetables. The authors concluded that the consumption of three or more servings a day of fruit or vegetables is not associated with a reduction in the risk of T2DM. This was similar to the results by Wu et al (2015) which showed that total fruit and vegetable consumption was not significantly associated with risk of T2DM. However, significant heterogeneity was shown for the combined effects of fruit and vegetables intake in the review by Hamer & Chaida (2007) [10, 21]. This was mostly due to the substantially lower risk estimate among women reported by the study by Ford and Mokdad (2001) [22]. Furthermore, showing somewhat different results, a meta-analysis carried out by Carter et al (2010) included six cohort studies, four of which included information on green leafy vegetable consumption. The pooled estimates showed no significant reduced risk from increasing the consumption of vegetables, fruit, or fruit and vegetables combined, results which accord with those in our current study. Nevertheless, the summary estimates from only four studies which assessed green leafy vegetable consumption showed that greater intake of green leafy vegetables was associated with a 14% reduction in risk of T2DM (hazard ratio 0.86, 95% confidence interval 0.77 to 0.97). A similar reduced risk for green leafy vegetables was also noted in two recent meta-analysis by Li et al, 2014 [11] and Cooper et al, 2015 [23]. However, most of the studies included in the meta-analysis included females only (4/6) and therefore the results may not be generalizable to a wider population.

Several possible mechanisms have been proposed to explain the potential associations between consuming more fruits and vegetables and green leafy vegetables in the diet, and the incidence of T2DM. Fruit and vegetables are rich in fibre, which has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion [24], though not all studies have found consistent associations with risk of T2DM [25]. On the other hand, many fruits are rich sources of fructose and fructose metabolism may decease insulin sensitivity and increase risk factors for metabolic syndrome and T2DM [26]. Increased intakes of fruit and vegetables have been shown to be inversely associated with obesity [27], which in turn is one of the most established risk factors for T2DM development [28]. The consumption of sugar sweetened fruit juices has also been positively associated with T2DM [29]. Green leafy vegetables confer antioxidant properties, which may mitigate T2DM risk through their high concentrations of β carotene, polyphenols and vitamin C [30, 31]. Additionally, green leafy vegetables could reduce the risk of T2DM due to their magnesium content, which has been shown to play a role in glucose control and improving insulin sensitivity [32]. Furthermore they are particularly rich in inorganic nitrate [33] which has been linked to improvement in reaction time in individuals with T2DM [34]. Thus these various putative mechanisms do not point consistently towards a single direction of effect for fruits and vegetable, making the inconsistent findings from observational studies, in which dose and pattern of consumption are recorded with variable precision, hardly surprising. It is also possible that other specific categories of fruit and vegetables are more closely associated with diabetes risk than overall fruit and vegetable intake, however we were not able to assess this in the current analysis. Intakes of fruit and vegetables are highly correlated with other lifestyle and dietary factors, and so it is difficult to isolate the effect of these intakes on T2DM independent of other factors. Consequently, when interpreting such disparate results, attempts must be made to control for some of the important confounders across the cohorts.

Our study has specific strengths and limitations. The main strength was the ability to compare cohorts from different countries which have harmonised the vast majority of variables using individual participant data. However, high levels of heterogeneity were found for the leafy green vegetable analysis (I2=79.3%, p=0.002) and differences in the classification of leafy green vegetables may exist between cohorts. Although all data were harmonised based on agreed rules (www.chancesfp7.eu; [16]), the data from the different cohorts are not perfectly comparable, due to differences in study design and data collection procedures, with the potential for residual inconsistencies in variable definitions. Although we made strenuous effort at harmonisation, the dietary assessment methods used in these studies differed with, for example, the total number of FFQ items differing across the cohorts and with EPIC elderly using more than one method (FFQ/24 hour diet recall). This may be a possible explanation for differences found across the cohorts. Similarly, the strengths of the meta-analysis may also be weaknesses where the possibility of the exposure is still heterogeneous for the same reason mentioned above. Individual study odds ratios are presented in Figures 1–4 and show the effects that each study has on the pooled effect estimate. Additionally, under-reporting and selective recall (of healthier foods) can be a problem with unpredictable consequences since dietary constituents are not consumed in isolation. Although we adjusted for several pertinent confounders, residual confounding from unmeasured risk factors cannot be ruled out. We were unable, for example, to analyse dietary patterns and had this been possible it may have shed additional light on the heterogeneity across cohorts, as in some countries the consumption of vegetables by older people correlates highly with intakes of red meat [35] and intakes of meat may be associated with diabetes risk [36]. A further consideration, which was not possible to explore in this study, is the impact of different cooking methods and of the ways fruits and vegetables are incorporated into meals, and the impact of both on overall micronutrient content [37].

Imprecision arising from a single measurement of diet at baseline may also have introduced some bias into this study, though classically this is often assumed to be towards the null [38]. In addition to this, lack of corroboration that the outcome used in this analysis is T2DM, which was an assumption made based on self-reported age of diagnosis, is a limitation of the study, though we do not believe that the precision of outcome verification should be differentially associated with the accuracy of any particular nutrient intake. Furthermore, the risk of under-ascertainment of diabetes might be greater in people who don’t visit their doctor very often and these are likely to be the people on healthier diets. This would however not be an explanation of our lack of finding an inverse association. Finally, although having a precise date of diagnosis for the cases ascertained in these CHANCES cohorts would have been preferable, the essentially null findings suggest that a time-to-event analysis may not have been particularly illuminating.

In summary, while there was some notable heterogeneity across cohorts, this study suggests that in older subjects there was no overall association between fruit, vegetable, green leafy vegetable, or cabbage and incident T2DM. Further studies are needed to assess these effects on T2DM risk in older people.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) [grant number HEALTH –F3-2010-242244]. This research was supported [in part] by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute. Cancer incidence data from the Atlanta metropolitan area were collected by the Georgia Center for Cancer Statistics, Department of Epidemiology, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia. Cancer incidence data from California were collected by the California Cancer Registry, California Department of Public Health’s Cancer Surveillance and Research Branch, Sacramento, California. Cancer incidence data from the Detroit metropolitan area were collected by the Michigan Cancer Surveillance Program, Community Health Administration, Lansing, Michigan. The Florida cancer incidence data used in this report were collected by the Florida Cancer Data System (Miami, Florida) under contract with the Florida Department of Health, Tallahassee, Florida. The views expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the FCDC or FDOH. Cancer incidence data from Louisiana were collected by the Louisiana Tumor Registry, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center School of Public Health, New Orleans, Louisiana. Cancer incidence data from New Jersey were collected by the New Jersey State Cancer Registry, Cancer Epidemiology Services, New Jersey State Department of Health, Trenton, New Jersey. Cancer incidence data from North Carolina were collected by the North Carolina Central Cancer Registry, Raleigh, North Carolina. Cancer incidence data from Pennsylvania were supplied by the Division of Health Statistics and Research, Pennsylvania Department of Health, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The Pennsylvania Department of Health specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations or conclusions. Cancer incidence data from Arizona were collected by the Arizona Cancer Registry, Division of Public Health Services, Arizona Department of Health Services, Phoenix, Arizona. Cancer incidence data from Texas were collected by the Texas Cancer Registry, Cancer Epidemiology and Surveillance Branch, Texas Department of State Health Services, Austin, Texas. Cancer incidence data from Nevada were collected by the Nevada Central Cancer Registry, Division of Public and Behavioral Health, State of Nevada Department of Health and Human Services, Carson City, Nevada.

We are indebted to the participants in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study for their outstanding cooperation. We also thank Sigurd Hermansen and Kerry Grace Morrissey from Westat for study outcomes ascertainment and management and Leslie Carroll at Information Management Services for data support and analysis.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standard: All of the cohorts obtained ethical approval and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Refrences

- 1.Neel JV. Diabetes mellitus: a “thrifty” genotype rendered detrimental by “progress”? American journal of human genetics. 1962;14(4):353. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Organization, W.H. Diabetes. 2011 www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs312/en/

- 3.King H, Dowd J. Primary prevention of type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1990;33(1):3–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00586454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tuomilehto J, Wolf E. Primary prevention of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1987;10(2):238–248. doi: 10.2337/diacare.10.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hämäläinen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S, Laakso M, Louheranta A, Rastas M. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344(18):1343–1350. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamman RF. Genetic and environmental determinants of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) Diabetes/metabolism reviews. 1992;8(4):287–338. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610080402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmet PZ. Primary prevention of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1988;11(3):258–262. doi: 10.2337/diacare.11.3.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stern MP. Kelly West Lecture: primary prevention of type II diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1991;14(5):399–410. doi: 10.2337/diacare.14.5.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manson JE, Stampfer M, Colditz G, Willett W, Rosner B, Hennekens C, Speizer F, Rimm E, Krolewski A. Physical activity and incidence of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in women. The Lancet. 1991;338(8770):774–778. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90664-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter P, Gray LJ, Troughton J, Khunti K, Davies MJ. Fruit and vegetable intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj. 2010:341. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li M, Fan Y, Zhang X, Hou W, Tang Z. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ open. 2014;4(11):e005497. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Y, Zhang D, Jiang X, Jiang W. Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases. 2015;25(2):140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper AJ, Forouhi NG, Ye Z, Buijsse B, Arriola L, Balkau B, Barricarte A, Beulens JW, Boeing H, Büchner FL. Fruit and vegetable intake and type 2 diabetes: EPIC-InterAct prospective study and meta-analysis. European journal of clinical nutrition. 2012;66(10):1082–1092. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2012.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boffetta P, Bobak M, Borsch-Supan A, Brenner H, Eriksson S, Grodstein F, Jansen E, Jenab M, Juerges H, Kampman E. The Consortium on Health and Ageing: Network of Cohorts in Europe and the United States (CHANCES) project—design, population and data harmonization of a large-scale, international study. European journal of epidemiology. 2014;29(12):929–936. doi: 10.1007/s10654-014-9977-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trichopoulou A, Orfanos P, Norat T, Bueno-de-Mesquita B, Ocké MC, Peeters PH, van der Schouw YT, Boeing H, Hoffmann K, Boffetta P. Modified Mediterranean diet and survival: EPIC-elderly prospective cohort study. Bmj. 2005;330(7498):991. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38415.644155.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schatzkin A, Subar AF, Thompson FE, Harlan LC, Tangrea J, Hollenbeck AR, Hurwitz PE, Coyle L, Schussler N, Michaud DS. Design and Serendipity in Establishing a Large Cohort with Wide Dietary Intake Distributions The National Institutes of Health–American Association of Retired Persons Diet and Health Study. American journal of epidemiology. 2001;154(12):1119–1125. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.12.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riboli E, Kaaks R. The EPIC Project: rationale and study design. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. International journal of epidemiology. 1997;26(suppl 1):S6. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.suppl_1.s6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jankovic N, Geelen A, Streppel MT, de Groot LC, Orfanos P, van den Hooven EH, Pikhart H, Boffetta P, Trichopoulou A, Bobak M. Adherence to a healthy diet according to the world health organization guidelines and all-cause mortality in elderly adults from Europe and the United States. American journal of epidemiology. 2014;180(10):978–988. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Control, C.f.D. National diabetes fact sheet. 2007. Retrieved June 30 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled clinical trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamer M, Chida Y. Intake of fruit, vegetables, and antioxidants and risk of type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of hypertension. 2007;25(12):2361–2369. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282efc214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ford ES, Mokdad AH. Fruit and vegetable consumption and diabetes mellitus incidence among US adults. Preventive medicine. 2001;32(1):33–39. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper AJ, Sharp Stephen J, Lentjes Marleen AH, Luben Robert N, Khaw Kay-Tee, Wareham Nicholas J, Forouhi Nita G. Dietary fibre and incidence of type 2 diabetes in eight European countries: the EPIC-InterAct Study and a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Diabetologia. 2015;58(7):1394–408. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3585-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yao B, Fang H, Xu W, Yan Y, Xu H, Liu Y, Mo M, Zhang H, Zhao Y. Dietary fiber intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: a dose–response analysis of prospective studies. European journal of epidemiology. 2014;29(2):79–88. doi: 10.1007/s10654-013-9876-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schulze MB, Schulz M, Heidemann C, Schienkiewitz A, Hoffmann K, Boeing H. Fiber and magnesium intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a prospective study and meta-analysis. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167(9):956–965. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.9.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanhope KL, Schwarz JM, Havel PJ. Adverse metabolic effects of dietary fructose: results from recent epidemiological, clinical, and mechanistic studies. Current opinion in lipidology. 2013;24(3):198. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3283613bca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ledoux T, Hingle M, Baranowski T. Relationship of fruit and vegetable intake with adiposity: a systematic review. Obesity Reviews. 2011;12(5):e143–e150. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdullah A, Peeters A, De Courten M, Stoelwinder J. The magnitude of association between overweight and obesity and the risk of diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2010;89(3):309–319. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xi B, Li S, Liu Z, Tian H, Yin X, Huai P, Tang W, Zhou D, Steffen LM. Intake of fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2014;9(3):e93471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agte V, Tarwadi K, Mengale S, Chiplonkar S. Potential of traditionally cooked green leafy vegetables as natural sources for supplementation of eight micronutrients in vegetarian diets. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 2000;13(6):885–891. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tarwadi K, Agte V. Potential of commonly consumed green leafy vegetables for their antioxidant capacity and its linkage with the micronutrient profile. International journal of food sciences and nutrition. 2003;54(6):417–425. doi: 10.1080/09637480310001622297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong JY, Xun P, He K, Qin LQ. Magnesium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(9):2116–2122. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lidder S, Webb AJ. Vascular effects of dietary nitrate (as found in green leafy vegetables and beetroot) via the nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 2013;75(3):677–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04420.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilchrist M, Winyard PG, Fulford J, Anning C, Shore AC, Benjamin N. Dietary nitrate supplementation improves reaction time in type 2 diabetes: development and application of a novel nitrate-depleted beetroot juice placebo. Nitric Oxide. 2014;40:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson S, Syddall H, Jameson K, Batelaan S, Martin H, Dennison EM, Cooper C, Sayer AA Group HS. Current patterns of diet in community-dwelling older men and women: results from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. Age and ageing. 2009:afp121. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song Y, Manson JE, Buring JE, Liu S. A prospective study of red meat consumption and type 2 diabetes in middle-aged and elderly women: the women’s health study. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(9):2108–15. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.9.2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Severi S, Bedogni G, Manzieri A, Poli M, Battistini N. Effects of cooking and storage methods on the micronutrient content of foods. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 1997;6:S21–S24. doi: 10.1097/00008469-199703001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clarke R, Shipley M, Lewington S, Youngman L, Collins R, Marmot M, Peto R. Underestimation of risk associations due to regression dilution in long-term follow-up of prospective studies. American journal of epidemiology. 1999;150(4):341–353. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]