To the Editor,

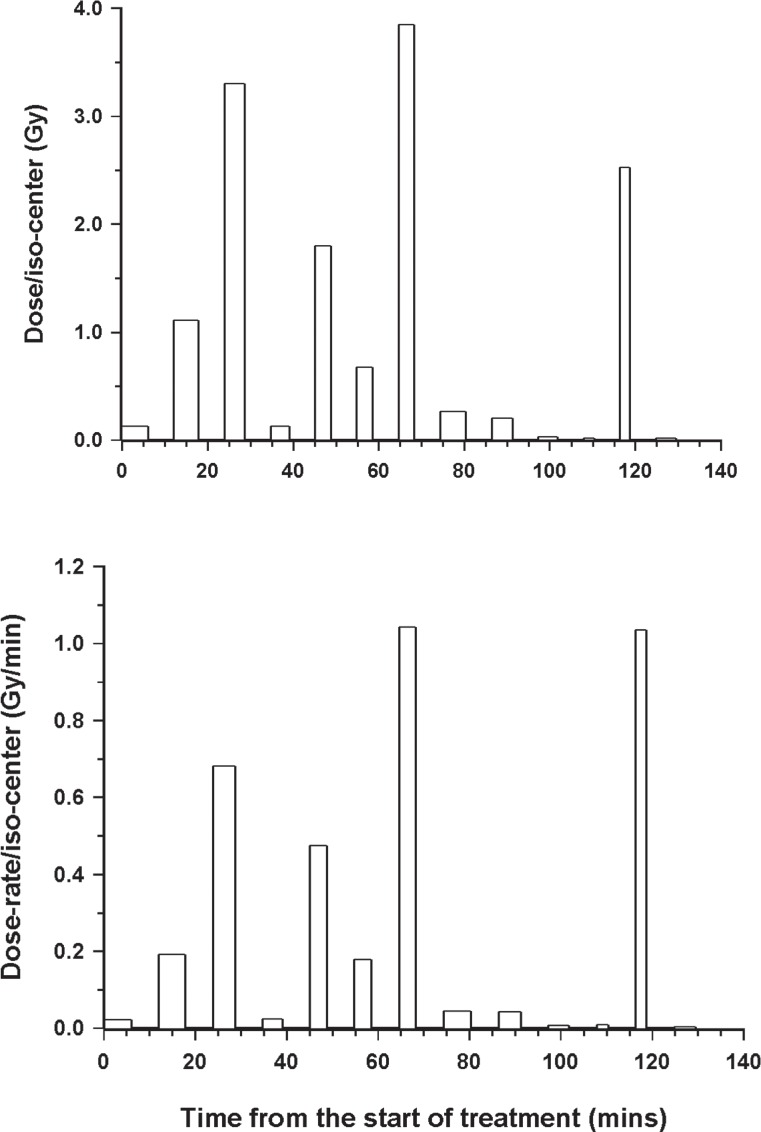

The recent publication by Niranjan et al1 in the Journal of Radiosurgery and SBRT, Y olume 1, issue 4 represents an attempt to address a long standing conundrum in Leksell Gamma Knife (LGK) stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) as to whether the activity of the Cobalt-60 (60Co) sources, in isolation, affect the biological effectiveness of this method of treatment. This publication, in common with others in this field, expresses the activity of the 60Co sources in terms of the calibration dose-rate of the equipment, representing in effect the dose-rate as measured in the Elekta ABS Calibration Phantom using a fixed sized collimator: a standard output measurement in conventional radiotherapy terminology. In the published study this dose-rate ranged from 0.77 – 2.936 Gy/min. However, as alluded to in the discussion of their manuscript these calibration dose-rates do not represent the actual dose-rates in the target volume of individual patients. Even when using a single iso-center the dose-rate in the target volume will be modulated by the selected collimator, if different from that used for calibration, and by the individual treatment volume geometry of the patients. This disparity between fixed calibration dose-rate and varying dose-rates in individually treated patients has been discussed elsewhere2 for cases of trigeminal neuralgia. This may seem like stating the obvious but it must be recognized that it is dose-rate in the target volume of an individual patient that influences the biological effectiveness of a specified dose in the target of that individual patient and not the calibration dose-rate factor per se. Thus caution is needed if conclusions are reached, based on the subdivision of patients based on the calibration dose-rate factor 3 and not the dose-rate in the individual patient. It is also pointed out in the discussion of the publication by Niranjan et al1 that as the number of iso-centers used in a treatment are increased, the treatment times are also generally increased because the tissue dose-rates are lower, when the dose is divided between more iso-centers, and because of the increasing number of time gaps between iso-centers. The latter applies, in particular, to machine models prior to Perfexion®.With increasing total exposure times, more time is available for the repair of sublethal radiation damage both over the periods of actual exposure (beam on time) and during the gaps (beam off times) between each of the iso-center exposures. In the gaps no additional damage is obviously induced but some repair does occur. The time-related dose-rates and dose profile changes for a patient treated for a Vestibular Schwannoma, over the course of treatment for an individual voxel receiving the prescription dose of 14 Gy on the 50% iso-surface, are illustrated in Figure 1. The different isocenter doses delivered to this specific voxel were 0.015 – 3.847 Gy given at dose-rates of between 0.0031 – 1.043 Gy/min. This to be compared with a calibration dose-rate of 2.963 Gy/min on the date this patient was treated. The dose-rates and dose profiles to other voxels on that same 50% physical iso-surface differed and thus for practical and reporting considerations this illustration would imply that the use of the phantom based single calibration dose-rate may, at best, be misleading.

Figure 1.

Time-related profile to show, for a randomly selected voxel on the 14 Gy prescription iso-surface (50% iso-dose), the variation in the dose delivered per iso-center (upper panel) and the variation in the dose-rate in in that same voxel (lower panel) for a patient treated for a with a Vestibular Schwannoma using a Series B LGK.

In the cell survival study1, the overall exposure times that were resultant on the use of calibration dose-rates of 0.77, 1.853 and 2.937 Gy/min with continuous exposures (no gaps) of 4, 8 and 16 Gy, when the cells were placed in the Elekta ABS calibration phantom, are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variation in overall treatment times (min) for 9L Gliosarcoma cells, irradiated with 4, 8 or 16 Gy at 0.77, 1.853 or 2.937 Gy/min in an Elekta ABS phantom.

| Dose (Gy) | Dose-rate (Gy/min) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.77 | 1.853 | 2.937 | |

| 4 | 5.19 | 2.16 | 1.36 |

| 8 | 10.39 | 4.32 | 2.72 |

| 16 | 20.78 | 8.63 | 5.45 |

The capacity to detect the repair of sublethal radiation induced injury in cells cannot just be based on dose-rate per se, but on the duration of exposures relative to the kinetics of repair of sublethal damage. Under optimal repair conditions no repair would likely to be detected if exposure times are short relative to any fast component of repair. Although the repair kinetic parameters for 9L Gliosarcoma cells, under optimal conditions, are not known, based on estimates in the literature both for tumor and normal tissue a value of 15 min for a rapid half-time for repair would not seem unreasonable4, 5, 6. The majority of the exposure times used in association with the published study1 (Table1) do not exceed a single halftime for repair and only in the case of 16 Gy were the difference between exposure times given at dose-rates of 2.937 and 0.77 Gy/min reach this order of magnitude. Thus at this dose level only the repair associated with approximately a single fast component of repair would have been detectable, provided that conditions for repair were optimal.

The conditions most relevant for the repair of sublethal damage are at a temperature of 37oC. Temperatures of < 10oC have been shown to totally inhibit the repair of sublethal damage7. For this reason experiments that examine the effects of dose-rate almost always use a temperature of 37oC including the classical dose-rate paper of Bedford and Mitchell8 and those studies related to a comparable issue to the use of the LGK, namely those showing a loss of efficacy when exposure treatment times were extended when moving from classical radiotherapy to intensity modulated radiation therapy9.

In the publication Niranjan et al1, cells were reported to be kept on ice prior to irradiation to ‘slow metabolism’ and no record was kept as to how temperatures changed over the limited exposure periods. However, they were clearly not optimal for the repair of sublethal damage, indeed for much of the period of irradiation it is likely that temperatures were below the level at which any of the limited repair that could possibly occur given the exposure times would have been unable to repair.

Thus both in terms of the exposure times and the irradiation conditions, this study which it was designed to look at in isolation the effect of changes in the activity of the 60Co sources on biological effectiveness was not appropriate. If the authors were planning further studies on tumor cell lines then exposure conditions should more closely mimic the clinical application of the LGK in SRS, including gaps, and use irradiation conditions which would be optimal for the repair of sublethal damage. It is also stated in the publication by Niranjan et al1 that studies are envisaged that would be related to normal tissue effects using neuronal cell lines. The authors should be aware that the cell population that is responsible for late normal tissue damage in the central nervous system (CNS) is not nerve cells directly since their loss or necrosis is secondary to radiation-induced effects on vascular endothelial cells in this tissue. Recent evidence for this has come from studies that have selectively irradiated the CNS endothelium in vivo10 or from those that involve the selective radioprotection of the vascular endothelium11.

REFERENCES

- 1. Niranjan A, Gobbel G, Novotny J, Jr., et al. Impact of decaying dose rate in gamma knife radiosurgery: in vitro study on 9L rat gliosarcoma cells. J Radiosurg SBRT 2012; 1:257-264. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hopewell JW, Millar WT, Lindquist C. Radiobiological principles: their application to gamma knife therapy. Prog Neurol Surg 2012; 25:39-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ari Y, Kando H, Lunsford DL, et al. Does the gamma knife dose rate affect the outcome in radiosurgery for trigeminal neuralgia? J Neurosurg 2010; 113: 168-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Guerrero M, Li XA. Extending the linear-quadratic model for large fraction doses pertinent to stereotactic radiotherapy. Phys Med Biol 2004; 49:4825-4835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Joiner MC, Mogili N, Marples B, et al. Significant dose can be lost by extended delivery times in IMRT with x rays but not high-LET radiations. Med Phys 2010; 37:2457-2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Millar WT, Hopewell JW. Effects of very low dose-rate 90Sr/90Y exposure on the acute moist desquamation response of pigskin: comparison based on predictions from dose fractionation studies at high dose-rate with incomplete repair. Radioth Oncol 2007; 83:187-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mason AJ, Giusti V, Green S, et al. Interaction between the biological effects of high- and low-LET radiation dose components in a mixed field exposure. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2011; 87: 1162-1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bedford JS, Mitchell JB. Dose-rate effects in synchronous mammalian cells in culture. Radiat Res 1973; 54:316-327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. X Mu, Lofroth PO, Karlsson M, et al. The effect of fraction time in intensity modulated radiotherapy: theoretical and experimental evaluation of an optimisation problem. Radiother Oncol 2003; 68:181-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Coderre JA, Morris GM, Micca PL, et al. Late effects of radiation on the central nervous system: role of vascular endothelial damage vs. glial stem cell survival. Radiat. Res. 2006; 166:495-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lyubimova N, Hopewell JW. Experimental evidence in support of the hypothesis that damage to the vascular endothelium plays a primary role in the development of late radiation-induced CNS injury. Brit. J. Radiol. 2004; 77:488–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]