Abstract

Neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF-2) represents the complex issue of hearing restoration after treatment for a patient with bilateral acoustic neuromas. This scenario is difficult for skull base teams considering that all treatment options (including observation of tumors) pose a risk to the patient for further or total hearing loss. In this case of a patient with bilateral deafness, restoration options were auditory brainstem or cochlear implantation (CI). The deciding factor for CI was based on the presence of a functioning cochlear nerve and blood supply. Ultimately, treatment with radiation therapy and subsequent CI proved effective as evidenced by dramatic improvement in communication (with lip reading cues) and speech perception on 1-year audiologic testing. Radiosurgery followed by CI may represent a potential emerging option for patients with NF-2.

Keywords: acoustic neuroma, vestibular schwannoma, cochlear implantation, auditory brainstem implantation, stereotactic radiosurgery, radiation therapy

1. INTRODUCTION

The management of vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas) includes observation with serial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and audiograms, microsurgical resection, fractioned radiotherapy, and stereotactic radiosurgery [1-3]. Each is associated with potential risks and benefits. Regardless of which approach is used, the primary objective is to prevent the potentially life-threatening complications of uncontrolled tumor growth and to preserve cranial nerve function, including facial nerve function and hearing. Treatment choice is even more challenging in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF-2), the hallmark of which is bilateral acoustic neuromas [4,5]. For these patients, treatment selection is influenced by patient preference, tumor size and growth, cranial nerve function, and the presence of contralateral disease. However, all treatments carry a significant risk of further hearing loss, and virtually all patients eventually need a long-term hearing restoration device.

For patients with NF-2, hearing options after surgical resection of both acoustic neuromas traditionally have included hearing aids initially and the possibility of auditory brainstem implantation (ABI). The ABI was designed for NF-2 because the disease and treatment itself are typically destructive to the cochlear nerve pathway; this implant works by directly stimulating the cochlear nucleus of the brainstem. Although an ABI can provide the patient with communicative assistance, the level of hearing achieved is usually limited to environmental sounds and assistance with lip-reading [4]. Recognition of speech without visual cues is often unmet, except in pediatric implantation for cochlear nerve aplasia [6]. In acoustic neuroma patients with preserved cochlear nerve anatomy and blood supply, interest has recently turned to cochlear implantation (CI) as an alternative to ABI.

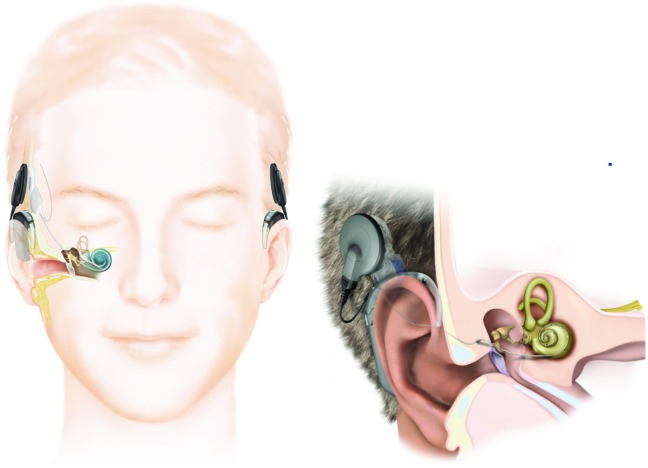

There is potential for favorable hearing outcomes with CI in non-acoustic neuroma patients [7] (Figure 1). One study investigating CI outcomes in patients with unilateral deafness reported both objective and subjective hearing scores that were comparable to individuals with normal hearing [8]. Reporting on the quality of life in 283 patients before and after implantation, Chung et al. noted improvements in the mental health, emotional/social functioning, and physical functioning at work after CI [9].

Figure 1.

Components of a cochlear implant system. Internal and external components shown on patient’s right whereas external-only components are on left. External component consists of a transmitter with a magnet and a sound processor with a microphone that fits behind the ear. An external device converts sound energy into electrical energy and communicates with the internal device. Internal components include a magnet (beneath the skin and behind the ear), a receiver that accepts input from the external components, and electrodes that directly enter the cochlea for stimulation of the cochlear nerve. Magnets on the internal and external systems allow physical alignment for optimal transcutaneous communication. Inset, Enlarged view of the external and internal components (with permission from Cochlear Americas).

With the promising results after CI placement, interest is increasing in preserving the integrity of the cochlear nerve during acoustic neuroma treatment, thus shifting away from ABI. To this end, we report the case of an NF-2 patient who underwent radiosurgery followed by CI placement 10 years later. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such report in the radiation oncology literature.

2. CLINICAL PRESENTATION

2.1 Case Report

INITIAL RADIOSURGERY. When a 57-year-old woman presented in 2002 with sudden-onset left-sided sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL), MRI revealed a 4 x 8-mm enhancing lesion of the internal auditory canal (IAC) consistent with an acoustic neuroma. She subsequently underwent Gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery in 2003 at an outside facility (these records were not obtained).

TEN YEARS LATER. When she developed sudden right-sided SNHL, MRI findings showed a stable left-sided acoustic neuroma and a new 3-mm right-sided IAC tumor with extension into the cochlea. With bilateral acoustic neuromas, she was diagnosed, by definition, with NF-2.

Treatment planning was focused on how to best preserve the patient’s serviceable hearing (i.e., hearing salvageable with a hearing aid). Given the intra-cochlear involvement of the right-sided tumor, CI would be contraindicated because the tumor would physically block electrode insertion. Therefore, treatment would include CI placement in her left ear, followed by right-sided microsurgical tumor resection and ABI placement. Audiologic testing before surgery revealed severe bilateral SNHL and a score of 0% in City University of New York (CUNY) sentence testing (i.e., no word recognition without visual/lip reading cues).

In 2013, a left cochlear implant (Nucleus Freedom, Cochlear, Lane Cove, Australia) was successfully placed without complication. We removed the internal magnet to permit future postoperative MRI scans (particularly important for NF-2 patients). Since activation, the patient has reported satisfactory daily use of the CI and dramatic improvement in communication along with lip reading cues. Audiologic testing 1 year after surgery showed significant improvement in speech perception with a 36% CUNY score. Considering her high satisfaction with her current hearing status, she opted for no additional rehabilitation. She also declined to undergo resection of the right-sided tumor, which has not grown, and subsequent ABI placement; this tumor is being followed with serial MRI scans at regular intervals.

The study was granted an exemption by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Cincinnati and consent for publication was waived.

3. DISCUSSION

Our patient with NF-2 faced the complexity of treatment choices for bilateral acoustic neuromas; that is, every available option (including observation) poses a potential risk of further or total hearing loss. Considering her bilateral deafness, the restoration options were ABI or CI; the decision for CI was based on the presence of a functioning cochlear nerve and blood supply (as noted by the preoperative audiogram that showed minimal residual hearing). Subsequently, CI that followed radiosurgery proved effective given her reported dramatic improvement in communication (with lip reading cues) and significantly improved speech perception scores at 1-year audiologic testing. With the strategy of radiosurgery followed by CI as a possible treatment for patients with NF-2, what makes this choice challenging is whether or not the cochlear nerve and blood supply is still present. If only radiosurgery or stereotactic radiation therapy were used before CI placement, the patient should have reasonable outcomes after CI placement. If prior surgery followed by radiation therapy were done, the presence of the cochlear nerve and/or blood supply is less assured. Therefore, the audiogram should assist in the selection of the ideal candidate as long as there is even a slight amount of residual hearing. However, this is not always clear or straightforward. .

3.1 Treatment Considerations

Microsurgical resection is currently preferred for mid-sized or large tumors (>3 cm) that are causing mass effect and obstructive hydrocephalus; in these cases, resection usually worsens preoperative hearing because of the often-inevitable transection of the cochlear nerve [1]. In contrast, surgical treatment of smaller tumors may allow preservation of the cochlear nerve. This would make postoperative cochlear implantation possible as long as the blood supply to the nerve is preserved.

Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) and fractioned radiotherapy have gained popularity. Patel et al. reported a 41% reduction (i.e., 178 cases per year) in microsurgical excision during a 6-year period from 2001 to 2007 with SRS as the likely explanation [17]. Similarly, Chen reported corresponding increases in the percentage of acoustic neuroma patients undergoing radiation: 20% in 2008, up from 5% in 1998, and 0% in 1983 [18].

With the recent increase in radiation-based treatment for NF-2, an additional consideration is the effect of the radiation dose delivered to the cochlea. Hearing preservation rates after radiosurgery have been correlated with total radiation dose delivered to the cochlea [19]. This becomes less important when CI placement is the plan from the outset of treatment because the devices do not require a functioning cochlea in order to restore hearing. That is, as long as the cochlear nerve is intact, the implant can still transmit the signal to the brain.

3.2 Considerations for NF-2 patients

Patients with NF-2 typically present with hearing that is worse in one ear and have several minimally invasive treatment options available for hearing restoration. Contralateral routing of signal (CROS) hearing aids transmit sound from the patient’s deaf side to his/her normal ear. The device consists of a microphone located on the deaf side of the head and an amplification device located on the normal ear. Sound is transmitted either through a wire worn around the back of the neck, or more commonly today, wirelessly [12]. For patients with deafness in one ear and subtotal hearing loss in the other, bilateral CROS (BiCROS) hearing aids may be used. The BiCROS functions not only as a standard hearing aid for the “good” ear, but it also receives input via a microphone from the contralateral “bad” ear. A third option, the bone-anchored hearing aid (BAHA), consists of a surgically implanted anchor into the skull that transmits sound to the contralateral inner ear through vibratory bone conduction.

Although all three options are excellent for improving hearing outcomes, they are only temporary solutions for NF-2 patients who will inevitably sustain total bilateral hearing loss. As mentioned earlier, the defining feature of NF-2 is bilateral acoustic neuromas. Whether from tumor progression or the treatment itself, eventually profound hearing loss develops in both ears. Once the patient reaches that point, ABI or CI placement are the only available options.

ABIs are implantable devices that bypass every step of the auditory pathway distal to the cochlear nucleus in the brainstem. The devices were first used more than 30 years ago in patients with NF-2 who sustained damage to the cochlear nerves during acoustic neuroma resection [5]. During surgical placement, the ABI electrode array is inserted through the foramen of Luschka so that it lies adjacent to the cochlear nucleus. However, variations in anatomy, imprecise placement, and the close proximity of adjacent brainstem structures are all complicating factors that work against the adequate placement of the electrode [5]. Nearby structures can also undergo incidental stimulation on activation of the ABI, clinically manifesting as vertigo and dysphagia [15]. Although an ABI can significantly and measurably improve communication, particularly in combination with lip reading [5], outcomes vary widely and are unpredictable. Consequently, surgeons should minimize a patient’s expectations regarding the hearing outcome potential with an ABI.

An ABI is the only option to regain hearing for individuals whose cochlear nerve and/or its blood supply are irreparably damaged intraoperatively. As expected, treatment modalities with a high risk of cochlear nerve damage (e.g., tumor resection) increase the likelihood that ABI will be the patient’s only option. However, in scenarios where the cochlear nerve can be spared, CI can be used. Cochlear implants bypass a nonfunctioning cochlea and use the cochlear nerve as a conduit to transmit the signal to the brain. The CI mimics the cochlea’s natural tonotopic organization, meaning that frequencies (pitches) are spread across its length. This organization is maintained throughout the auditory pathway, all the way to the primary auditory cortex. CI surgery includes a mastoidectomy to gain access to the middle ear. An electrode is then placed through or adjacent to the round window and into the scala tympani of the cochlea. Significant complications are rare. Patients are typically discharged the same day or observed overnight. When compared with ABI, CI surgical outcomes are less varied and generally far more favorable [16]. The procedure itself is surgically less complex, and there is less variability in outcomes when compared to ABIs.

While a previous study has examined the long-term outcome of NF-2 patients who underwent cochlear implantation after surgical tumor resection [7], there is a paucity of literature to examine CI after stereotactic radiosurgery [26]. Our patient’s case demonstrates that this treatment regimen is capable of providing dramatic improvements in communication with lip reading cues as well as significant improvements in speech perception at 1-year audiologic testing.

NF-2 is a disorder that results in bilateral deafness, which is the original indication for cochlear implantation. Recently, interest has turned to using CIs to treat patients with unilateral deafness. If the cochlear nerve and its blood supply are intact, the combination of stereotactic radiosurgery followed by cochlear implantation represents an exciting treatment alternative for not only NF-2, but also for patients with a unilateral, sporadic acoustic neuroma. The percentage of all intracranial tumors accounted for by acoustic neuromas is not insignificant (approximately 8% of intracranial tumors are acoustic neuromas). Only a fraction of those acoustic neuromas arise in NF-2 patients. If the cochlear nerve can be left intact, the combination of stereotactic radiosurgery followed by a CI might have a significant and positive impact in preserving the quality of life in patients with acoustic neuromas, regardless of whether the patient has NF-2 or a sporadic acoustic neuroma.

4. CONCLUSION

Patients with NF-2 will invariably suffer from complete bilateral SNHL. Prompt and early diagnosis and treatment is paramount for minimizing the risks associated with tumor growth and for the preservation of serviceable hearing. A paradigm shift during the last 30 years in the treatment selected by physicians and their patients shows a decrease in microsurgical resection and an increase in observation and stereotactic radiosurgery. Once treatment is provided, the next decision is if ABI or CI would be the best hearing restoration option. Our patient’s case demonstrates the utility of radiosurgery with subsequent cochlear implantation in the treatment of small vestibulocochlear nerve tumors. When compared with ABI, CI’s more favorable risk profile and audiologic outcomes may be enough to promote treatment plans in which candidacy through cochlear nerve and blood supply preservation is more likely.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NF-2

neurofibromatosis type 2

- ABI

auditory brainstem implantation

- CI

cochlear implantation

- CUNY

City University of New York

- CROS

contralateral routing of signal

- FM

frequency modulation

- BAHA

bone-anchored hearing aid

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- SRS

stereotactic radiosurgery

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

Dr. Samy reports research and honorarial support from Cochlear Corporation and research support from MedEll Corp, outside the submitted work. Drs Costello, Golub, Barrord, Pater, and Pensak reported no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Conception and design: Ravi N. Samy.

Data collection: John V. Barrord, Mark S. Costello.

Data analysis and interpretation: John V. Barrord, Mark S. Costello.

Manuscript writing: John V. Barrord, Mark S. Costello, Justin S. Golub, Luke Pater, Ravi N. Samy.

Final approval of manuscript: Justin S. Golub, Luke Pater, Ravi N. Samy, Myles L. Pensak.

REFERENCES

- 1.Theodosopoulos PV, Pensak ML. (2011) Contemporary management of acoustic neuromas. Laryngoscope 121: 1133-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lustig LR, Yeagle J, Driscoll CLW, Blevins N, Francis H, Niparko JK. (2006) Cochlear implantation in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2 and bilateral vestibular schwannomas. Otol Neurotol 27: 512-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lunsford LD, Niranjan A, Flickinger JC, Maitz A, Kondziolka D. (2205) Radiosurgery of vestibular schwannomas: summary of experience in 829 cases. J Neurosurg 102(Suppl): 195-199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trotter MI, Briggs RJS. (2010) Cochlear implantation in neurofibromatosis type 2 after radiation therapy. Otol Neurotol 31: 216-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz MS, Otto SR, Shannon RV, Hitselberger WE, Brackmann DE. (2008) Auditory brainstem implants. Neurotherapeutics 5: 128-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchman CA, Teagle HFB, Roush PA, Park LR, Hatch D, Woodard J, Zdanski C, Adunka OF. (2011) Cochlear implantation in children with labyrinthine anomalies and cochlear nerve deficiency: implications for auditory brainstem implantation. Laryngoscope 121: 1979-1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neff BA, Wiet RM, Lasak JM, Cohen NL, Pillsbury HC, Ramsden RT, Welling DB. (2007) Cochlear implantation in the neurofibromatosis type 2 patient: long-term follow-up. Laryngoscope 117: 1069-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Távora-Vieira D, Boisvert I, Mcmahon CM, Maric V, Rajan GP. (2013) Successful outcomes of cochlear implantation in long-term unilateral deafness: brain plasticity? NeuroReport 24: 724-729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung J, Chueng K, Shipp D, Friesen L, Chen JM, Nedzelski JM, Lin VYW. (2012) Unilateral multi-channel cochlear implantation results in significant improvement in quality of life. Otol Neurotol 33: 566-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kandathil CK, Dilwali S, Wu C, Ibrahimov M, Mckenna MJ, Lee H, Stankovic KM. (2014) Aspirin intake correlates with halted growth of sporadic vestibular schwannoma in vivo. Otol Neurotol 35: 353-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matthies C, Brill S, Varallyay C, Solymosi L, Gelbrich G, Roosen K, et al. (2013) Auditory brainstem implants in neurofibromatosis type 2: is open speech perception feasible? J Neurosurg 120: 546-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hol MKS, Kunst SJW, Snik AFM, Cremers CWRJ. (2010) Pilot study on the effectiveness of the conventional CROS, the transcranial CROS and the BAHA transcranial CROS in adults with unilateral inner ear deafness. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 267: 889-896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin TPC, Lowther R, Cooper H, Holder RL, Irving RM, Reid AP, Proops DW. (2010) The bone-anchored hearing aid in the rehabilitation of single-sided deafness: experience with 58 patients. Clin Otolaryngol 35: 284-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanna M, Lella FD, Guida M, Merkus P. (2012) Auditory brainstem implants in NF2 patients: results and review of literature. Otol Neurotol 33: 154-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sennaroglu L, Ziyal I. (2012) Auditory brainstem implantation. Auris Nasus Larynx 39: 439-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vincenti V, Pasanisi E, Guida M, Trapani GD, Sanna M. (2008) Hearing rehabilitation in neurofibromatosis type 2 Patients: cochlear versus auditory brainstem implantation. Audiol Neurotol 13: 273-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel S, Nuño M, Mukherjee D, Nosova K, Lad SP, Boakye M, et al. (2013) Trends in surgical use and associated patient outcomes in the treatment of acoustic neuroma. World Neurosurg 80: 142-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen DA. (2007) Acoustic neuroma in a private neurotology practice: trends in demographics and practice patterns. Laryngoscope 117: 2003-2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Timmer FCA, Hanssens PEJ, Van Haren AEP, Mulder JJS, Cremers CWRJ, Beynon AJ, et al. (2009) Gamma knife radiosurgery for vestibular schwannomas: results of hearing preservation in relation to the cochlear radiation dose. Laryngoscope 119: 1076-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Combs SE, Welzel T, Schulz-Ertner D, Huber PE, Debus J. (2010) Differences in clinical results after LINAC-based single-dose radiosurgery versus fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for patients with vestibular schwannomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 76: 193-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Temple RH, Axon PR, Ramsden RT, Kelest N, Deger K, Yücel E. (199) Auditory rehabilitation in neurofibromatosis type 2: a case for cochlear implantation. J Laryngol Otol 113: 161-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mukherjee P, Ramsden JD, Donnelly N, Axon P, Saeed S, Fagan P, Irving RM. (2013) Cochlear implants to treat deafness caused by vestibular schwannomas. Otol Neurotol 34: 1291-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pai I, Dhar V, Kelleher C, Nunn T, Connor S, Jiang D, O’Connor AF. (2013) Cochlear implantation in patients with vestibular schwannoma: a single United Kingdom center experience. Laryngoscope 123: 2019-2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Babu R, Sharma R, Bagley JH, Hatef J, Friendman AH, Adamson C. (2013) Vestibular schwannomas in the modern era: epidemiology, treatment trends, and disparities in management. J Neurosurgery 119:121-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan M, Myrie OA, Lin FR, Niparko JK, Minor LB, Tamargo RJ, Francis HW. (2010) Trends in the management of vestibular schwannomas at Johns Hopkins 1997-2007. Laryngoscope 120:144-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carlson ML, Breen JT, Driscoll CL, Link MJ, Neff BA, Gifford RH, Beatty CW. (2012) Cochlear implantation in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2: variables affecting auditory performance. Otol Neurotol 33(5): 853-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]